How does tele-learning compare with other forms of education delivery? A systematic review of tele-learning educational outcomes for health professionals

Jo Tomlinson A E , Tim Shaw A , Ana Munro A , Ros Johnson B , D. Lynne Madden C , Rosemary Phillips D and Deborah McGregor AA Faculty of Medicine, The University of Sydney

B NSW Kids and Families, NSW Ministry of Health

C School of Medicine, Sydney, The University of Notre Dame (formerly Public Health Training and Workforce, NSW Ministry of Health)

D Statewide and Rural Health Service and Capital Planning, NSW Ministry of Health

E Corresponding author. Email: jo.tomlinson@sydney.edu.au

NSW Public Health Bulletin 24(2) 70-75 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB12076

Published: 7 November 2013

Abstract

Telecommuniciation technologies, including audio and videoconferencing facilities, afford geographically dispersed health professionals the opportunity to connect and collaborate with others. Recognised for enabling tele-consultations and tele-collaborations between teams of health care professionals and their patients, these technologies are also well suited to the delivery of distance learning programs, known as tele-learning. Aim: To determine whether tele-learning delivery methods achieve equivalent learning outcomes when compared with traditional face-to-face education delivery methods. Methods: A systematic literature review was commissioned by the NSW Ministry of Health to identify results relevant to programs applying tele-learning delivery methods in the provision of education to health professionals. Results: The review found few studies that rigorously compared tele-learning with traditional formats. There was some evidence, however, to support the premise that tele-learning models achieve comparable learning outcomes and that participants are generally satisfied with and accepting of this delivery method. Conclusion: The review illustrated that tele-learning technologies not only enable distance learning opportunities, but achieve comparable learning outcomes to traditional face-to-face models. More rigorous evidence is required to strengthen these findings and should be the focus of future tele-learning research.

Telecommunications are increasingly being used by the health professions to deliver health care services and to exchange health information across distances. Telehealth, tele-collaborations and tele-consultations are contributing to improvements in the quality, availability and efficiency of health care services to distance locations.1 Telehealth, for example, enables existing forms of interactions between health care providers and recipients to occur at a distance, through the use of telecommunications.2 Similarly, distance learning methods utilising telecommunication technologies are helping to overcome the challenges of engaging in traditional forms of education across distances. Referred to as ‘tele-learning’, it involves making connections among people and resources, and transferring images and voice data via communication technologies, for learning-related purposes.3,4

Like telehealth, tele-learning utilises telecommunications to connect participants, helping to alleviate barriers to accessing learning opportunities and enriching distance learning experiences. The relative ease of use and availability of telecommunication technologies means that audioconferencing (teleconferencing) and videoconferencing are well established and frequently used communication mechanisms for staff in the health sector.5 For the purpose of this review, the term ‘tele-learning’ describes the use of video and/or audio-based technologies for distance learning purposes.

Enabling collaborations between geographically distributed health workers makes the use of telecommunications especially relevant to professionals working in rural and remote areas.6 NSW Health has made substantial investments in telecommunication infrastructure, making tele-learning more readily accessible within education and clinical facilities,7 although it should be noted that the financial implications of tele-learning were outside the scope of this review.

This review sought to establish whether education using tele-learning methods results in equivalent learning outcomes when compared to traditional face-to-face methods. The review was commissioned by NSW Health to ascertain whether there was an evidence base to support the use of videoconferencing to develop and deliver educational programs to health professionals (videoconferencing being one way of enabling clinicians working in rural and remote areas to have access to continual professional development and educational programs).

Methods

A systematic review was conducted to identify literature relevant to the use of tele-learning technologies in delivering education and training materials/programs to health professionals. A review of abstracts refined the results to literature reporting on learning outcomes achieved from tele-learning interventions. Researchers and review stakeholders from the public health sector collaborated in the formulation and refinement of the specific review questions and search parameters.

Review questions translated into the following search terms; videoconference/ing, tele-learning, tele-education, telehealth, telemedicine, teleconference/ing, audio conference/ing, videostreaming, education, learning outcomes, multidiscipline/ary, face-to-face, professional development, continuing medical education, distance education, distance learning, podcast/ing and vodcast/ing.

Information sources

The following medical and educational databases were the basis for the search: MEDLINE, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, American College of Physicians Journal Club, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PubMed, University of Sydney catalogue search (Summon search), PsycINFO, Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC), British Education Index (BEI), and Google Scholar.

Reference lists from original articles were utilised to identify relevant literature and two frequently cited journals were searched by hand: Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare and Telemedicine and e-Health. An internet search for relevant literature, including grey literature sources, was conducted using the Google search engine and other government and education databases.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The search focused primarily on the education of health professionals, but also included tertiary students.

The review included both synchronous (content delivered simultaneously to face-to-face and tele-learning cohorts) and asynchronous delivery models (content delivered to the cohorts at different times). Studies utilising desktop computers and the internet were included where the technologies were used for televised conferencing, including synchronous and asynchronous streamed lectures. The review excluded facilitated e-learning and online education models such as the use of social networking, blogs, wikis and Blackboard™ learning management system software.

Results published prior to 2000 were excluded from the review as it was considered they would not incorporate the technologies currently available. Other exclusions included: papers discussing education and training interventions at lower than bachelor levels; health care delivery via telemedicine; and papers primarily focused on the technical specifications/IT equipment requirements for videoconferencing. Due to the relatively low number of randomised controlled trials and other rigorous methodological studies, searches were not limited, in the first instance, by study type. The search included qualitative, comparative, observational and evaluation studies, randomised controlled trials and systematic reviews.

Results

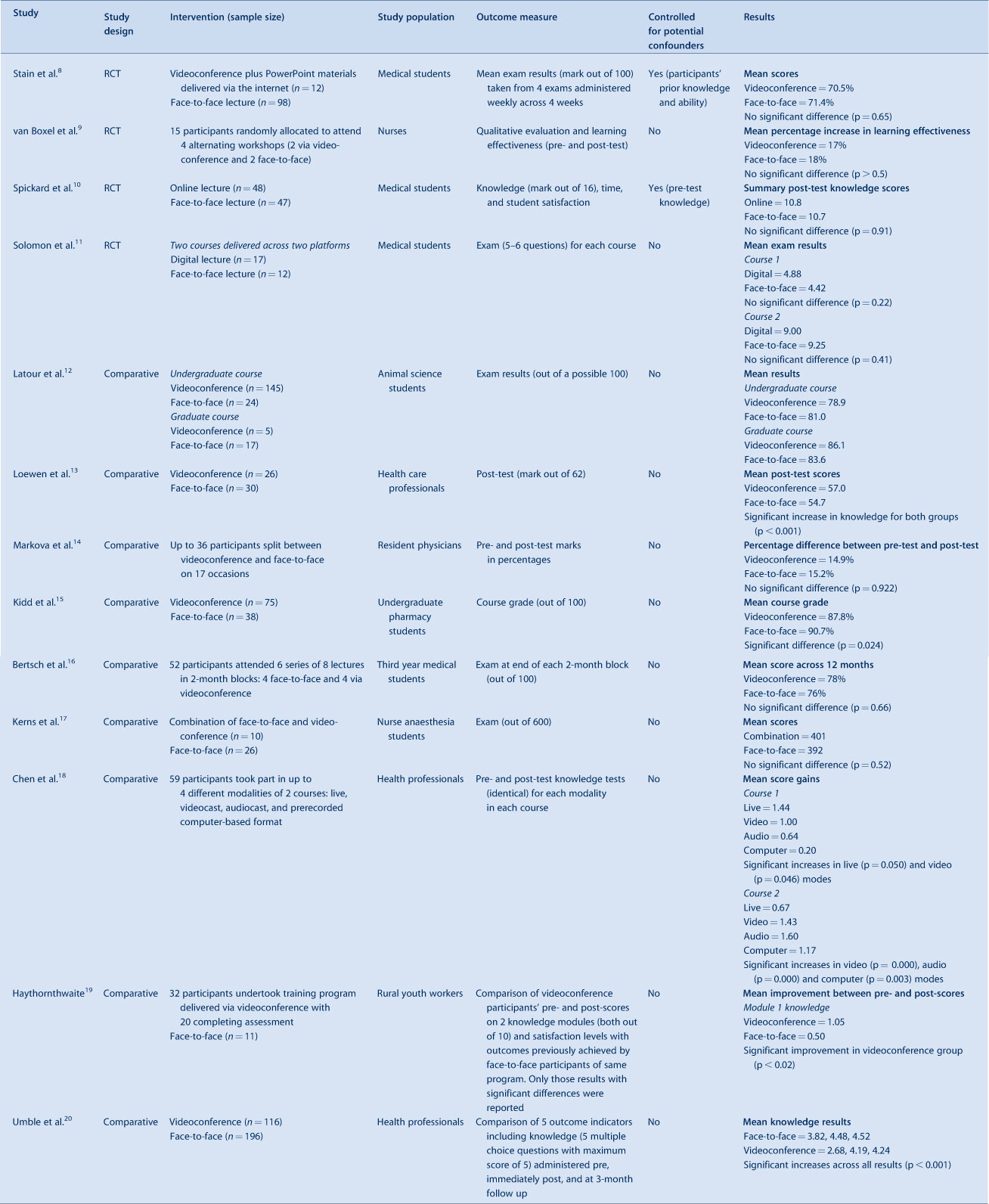

The search retrieved 47 records. Of these, four randomised controlled studies8–11 and nine comparative studies12–20 were identified as measuring learning outcomes of tele-learning versus traditional face-to-face education. The remaining 34 papers were either descriptive observational studies or did not measure tele-learning versus face-to-face education and so were excluded from the review. While the 13 included studies (summarised in Table 1) reported comparable learning outcomes achieved by the delivery methods, the scientific rigour of these studies was not strong; this needs to be considered when drawing conclusions from the literature. Many of these studies noted a failure to control for variables such as participant prior knowledge and ability, instructor experience and methods, and instructor and participant familiarity with technology. Limitations also included small sample sizes and non-random selection of participants. As mentioned, studies focused on health professionals and tertiary students.

|

Two of the randomised controlled studies8,9 compared traditional didactic institution-based lectures with interactive synchronous videoconference lectures. Both studies found no significant difference in knowledge acquisition or learning outcomes. In addition to the synchronous delivery of a lecture via videoconference, one of these studies8 delivered PowerPoint materials to remote participants via the internet. The first study8 involved 110 surgical clerkship students, however only 12 of these students participated in the videoconferencing intervention. The second study9 involved 15 community nurses, with the low sample sizes attributed to recruitment and facility capacity limitations.

One study compared the learning outcomes of 95 medical students allocated to either attend live lectures or use the internet to access and view the streamed lecture on a desktop computer.10 The streamed lecture consisted of a PowerPoint presentation with optional audio accompaniment. The delivery mode was asynchronous, meaning that students could view the material at any time and there was no interaction between the lecturer and student. Summary post-test scores were almost identical (10.8 vs 10.7 out of a possible 16 for online and face-to-face modes, respectively); no statistically significant difference was found between the two modes of delivery.

The fourth controlled trial11 compared face-to-face lectures with a digital lecture format, similar to streaming (but using the previous year’s lectures sent to students in CD-ROM format), to compare performances of 29 third year medical students across two courses. Again, mean exam results for both courses were very similar between those who attended the face-to-face lectures (achieving 4.42 and 9.25 respectively) and those who utilised the distance learning format of the lectures (achieving 4.88 and 9.0 respectively).

The nine comparative studies12–20 further reinforced comparable learning outcomes for face-to-face and tele-learning delivery formats. Of note, videoconferencing was the prominent tele-learning method utilised by the majority of the comparative studies. Studies involving participants from multidisciplinary neonatal care teams,13 pharmacology,15 medicine,14,16 and nursing17 all demonstrated that there was little or no difference in learning outcomes when comparing traditional classroom instruction with distance learning via interactive videoconference. While a study on mental health training for workers19 based in rural centres found significant improvement in knowledge for the videoconference participants, similar learning outcomes were achieved across both groups.

One comparative study18 assessed multiple tele-learning methods, including simultaneous videocast of the live lecture, simultaneous audiocast of the live lecture, and a pre-recorded computer-based format, with the live lecture format. Significant increases in knowledge gain were demonstrated across multiple delivery modes with evaluation of user feedback showing similar levels of interest and acceptability.

Another comparative study20 of a large national immunisation continuing education course for the public health workforce in the United States demonstrated comparable outcomes for classroom and distance (satellite broadcasted) trained participants. The study concluded that classroom and distance delivery methods have comparable outcomes in continuing education and can foster the implementation of practice guidelines and recommendations.

Most of the included studies reported qualitative participant satisfaction results. In terms of satisfaction with tele-learning versus traditional face-to-face education models, participants routinely reported a high level of acceptability and satisfaction with tele-learning delivery models11,13–15 but a preference for traditional face-to-face models.10,12

Discussion

The literature indicates that tele-learning can provide an effective means of delivering educational outcomes for health professionals.

The majority of the available literature on tele-learning is descriptive or observational. This review focused on randomised controlled trials and comparative studies. Caution must be taken when interpreting the results of these studies as they often lacked an established evaluation framework, and failed to control for independent variables such as participants’ prior knowledge and ability, instructor experience and methods, and instructor and participant familiarity with technology. Limitations also included small sample sizes and non-random selection of participants.

Despite limited rigorous evidence, the available literature supports the notion that tele-learning methods achieve comparable learning outcomes when compared with traditional face-to-face learning methods.

Two studies indicated participant preference for more traditional face-to-face education delivery methods over tele-learning methods. However, the literature also indicated a high level of participant satisfaction with tele-learning methods, with many participants indicating that they would partake in future tele-learning opportunities or recommend these opportunities to others. Two studies reported a perception that tele-learning should only be used when face-to-face is not feasible and should complement rather than replace traditional teaching.5,21 Therefore, like Birden and Page,22 we could surmise that tele-learning is a useful adjunct to traditional learning methods.

Conclusion

The literature supports tele-learning as an effective means of delivering education that can achieve learning outcomes that are comparable to traditional face-to-face learning methods. The utility of tele-learning infrastructure for enabling distance learning opportunities should be considered. However, the limited availability of rigorous evidence highlights the need for further research to reinforce the equivalency of tele-learning delivery methods.

Acknowledgments

The systematic review which underpins this paper was funded by the Telehealth Unit, Statewide and Rural Health Service and Capital Planning Branch, NSW Ministry of Health, and brokered by The Sax Institute for NSW Health. The research was completed by the Workforce Education Development Group which is part of Sydney Medical School, The University of Sydney.

References

[1] Maeder A. Telehealth Standards Directions Supporting Better Patient Care. HIC 2008 Conference: Australia's Health Informatics Conference. Melbourne, Vic. Health Informatics Society of Australia.[2] Currell R, Urquhart C, Wainwright P, Lewis R. Telemedicine versus face to face patient care: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000; CD002098

| 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3c3lsl2nsA%3D%3D&md5=40cf6efca33fc1bf470495aec069c43cCAS | 10796678PubMed |

[3] Moonen J. The efficiency of telelearning. J Asynchronous Learn Netw 1997; 1 68–77.

[4] Taylor JC. Distance education technologies: The fourth generation. Australian Journal of Education Technology 1995; 11 1–7.

[5] Naylor C, Madden DL, Neville L, Oong DJ. Pilot study of using a web and teleconference for the delivery of an Epi Info training session to public health units in NSW, 2005. N S W Public Health Bull Supplementary Series 2009; 20 22–37.

[6] Newman C, Martin E, McGarry DE, Cashin A. Survey of a videoconference community of professional development for rural and urban nurses. Rural Remote Health 2009; 9 1134

| 19382828PubMed |

[7] Sackett KM, Campbell-Heider N, Blyth JB. The evolution and evaluation of videoconferencing technology for graduate nursing education. Comput Inform Nurs 2004; 22 101–6.

| The evolution and evaluation of videoconferencing technology for graduate nursing education.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | 15520574PubMed |

[8] Stain SC, Mitchell M, Belue R, Mosely V, Wherry S, Adams CZ, et al. Objective assessment of videoconferenced lectures in a surgical clerkship. Am J Surg 2005; 189 81–4.

| Objective assessment of videoconferenced lectures in a surgical clerkship.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | 15701498PubMed |

[9] van Boxel P, Anderson K, Regnard C. The effectiveness of palliative care education delivered by videoconferencing compared with face-to-face delivery. Palliat Med 2003; 17 344–58.

| The effectiveness of palliative care education delivered by videoconferencing compared with face-to-face delivery.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar |

[10] Spickard A, Alrajeh N, Cordray D, Gigante J. Learning about screening using an online or live lecture: does it matter? J Gen Intern Med 2002; 17 540–5.

| Learning about screening using an online or live lecture: does it matter?Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | 12133144PubMed |

[11] Solomon DJ, Ferenchick GS, Laird-Fick HS, Kavanagh K. A randomised trial comparing digital and live lecture formats. BMC Med Educ 2004; 4 27

| A randomised trial comparing digital and live lecture formats.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | 15569389PubMed |

[12] Latour MA, Collodi P. Evaluating the performance and acceptance of teleconference instruction versus traditional teaching methods for undergraduate and graduate students. Poult Sci 2003; 82 36–9.

| 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3s%2FmvFyrtg%3D%3D&md5=93cef735540e2e531467939f3fba509eCAS | 12580242PubMed |

[13] Loewen L, Seshia MM, Fraser Askin D, Cronin C, Roberts S. Effective delivery of neonatal stabilization education using videoconferencing in Manitoba. J Telemed Telecare 2003; 9 334–8.

| Effective delivery of neonatal stabilization education using videoconferencing in Manitoba.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3srpvFGrsw%3D%3D&md5=8f17b910fa1d8dad7ebfa56a1b683875CAS | 14680517PubMed |

[14] Markova T, Roth LM, Monsur J. Synchronous distance learning as an effective and feasible method for delivering residency didactics. Fam Med 2005; 37 570–5.

| 16145635PubMed |

[15] Kidd RS, Stamatakis MK. Comparison of students' performance in and satisfaction with a clinical pharmacokinetics course delivered live and by interactive videoconferencing. Am J Pharm Educ 2006; 70 10

| Comparison of students' performance in and satisfaction with a clinical pharmacokinetics course delivered live and by interactive videoconferencing.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | 17136153PubMed |

[16] Bertsch TF, Callas PW, Rubin A, Caputo MP, Ricci MA. Effectiveness of lectures attended via interactive video conferencing versus in-person in preparing third-year internal medicine clerkship students for Clinical Practice Examinations (CPX). Teach Learn Med 2007; 19 4–8.

| 17330992PubMed |

[17] Kerns AS, McDonough JP, Groom JA, Kalynych NM, Hogan GT. Televideo conferencing: is it as effective as “in person” lectures for nurse anesthesia education. AANA J 2006; 74 19–21.

| 16483063PubMed |

[18] Chen T, Buenconsejo-Lum L, Braun KL, Higa C, Maskarinec GG. A Pilot Evaluation of Distance Education Modalities for Health Workers in the US – Affiliated Pacific Islands. Developing Human Resources in the Pacific 2007; 14 20–8.

[19] Haythornthwaite S. Videoconferencing training for those working with at-risk young people in rural areas of Western Australia. J Telemed Telecare 2002; 8 29–33.

| Videoconferencing training for those working with at-risk young people in rural areas of Western Australia.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | 12661614PubMed |

[20] Umble KE, Cervero RM, Yang B, Atkinson WL. Effects of traditional classroom and distance continuing education: a theory-driven evaluation of a vaccine-preventable diseases course. Am J Public Health 2000; 90 1218–24.

| Effects of traditional classroom and distance continuing education: a theory-driven evaluation of a vaccine-preventable diseases course.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3cvhs1Cgtw%3D%3D&md5=98c3d791d234d7844cabf78b46de965eCAS | 10937000PubMed |

[21] Strehle EM, Earle G, Bateman B, Dickson K. Teaching medical students pediatric cardiovascular examination by telemedicine. Telemed J E Health 2009; 15 342–6.

| Teaching medical students pediatric cardiovascular examination by telemedicine.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | 19441952PubMed |

[22] Birden H, Page S. Teaching by videoconference: a commentary on best practice for rural education in health professions. Rural Remote Health 2005; 5 356–63.

| 16004531PubMed |