Research evidence can successfully inform policy and practice: insights from the development of the NSW Health Breastfeeding Policy

Debra J. Hector A , April N. Hyde B , Ruth E. Worgan A and Edwina L. Macoun C DA NSW Centre for Public Health Nutrition, University of Sydney

B Primary Health and Community Partnerships Branch, NSW Department of Health

C Centre for Health Advancement, NSW Department of Health

D Corresponding author. Email: edwina.macoun@doh.health.nsw.gov.au

NSW Public Health Bulletin 19(8) 138-142 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB07041

Published: 20 October 2008

Abstract

Strengthening the bridge between research and policy has been identified as a priority if evidence-based policy is to become the norm. However, current understanding of the research–policy interface is limited. A recent policy in NSW was the first evidence-based directive with specific actions to promote and support breastfeeding within a state health system in Australia. This paper explores the development of this policy, highlighting the factors that facilitated the incorporation of research evidence into the policy.

The funding of a research centre to support NSW Health policy and workforce development was significant to the process. The existing organisational linkage ensured that the research evidence was identified, synthesised and effectively communicated, with the needs of the research users in mind and within a clear framework to guide action. The research evidence was not only strong, but also relevant with regard to prevailing political interests. The process was strengthened by the commitment of key researchers and policy makers to breastfeeding. Other types of evidence were considered, including the expert opinions of senior service providers regarding the capacity to act on the research evidence.

Current understanding of the process of ‘getting research into policy and practice’ is limited, yet an understanding of the process has been highlighted as critical in promoting effective and sustained public health action.1 Strengthening the bridge between research and policy is a priority if evidence-based policy is to become the norm, rather than the exception.2

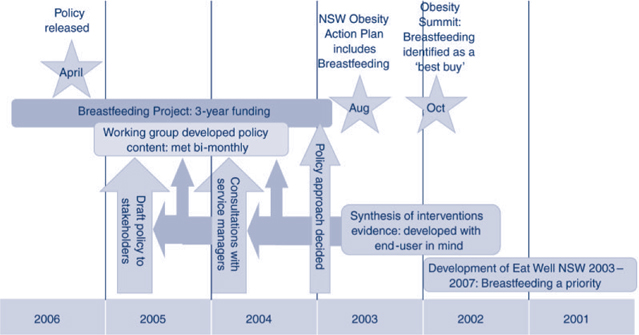

A recently released policy, Breastfeeding in NSW: Promotion, Protection and Support, was the first evidence-based directive in Australia with specific actions to promote and support breastfeeding within a state health system.3 An exploration of the development of this policy provides insights into the research-policy interface.4 Figure 1 illustrates key events in the policy development process.

|

Policy development process

Historical context and political will

The stage was set for action to be taken to support breastfeeding at the population level in New South Wales (NSW) during the 1990s. Around this time there was:

-

an accumulating evidence base highlighting the multiple health benefits of breastfeeding5

-

monitoring evidence showing that the majority of mothers in NSW do not feed their infants according to national health recommendations6–9

-

several policies and strategies at the national and international level strongly recommending breastfeeding as the most appropriate method for feeding infants9,10

-

an identification of the promotion of breastfeeding as one of five nutrition priorities for NSW11

-

a comprehensive review of interventions research identifying evidence-based policy and practice recommendations on breastfeeding.12

Nevertheless, progress at this time was limited.

A pivotal event occurred in 2002. The NSW Childhood Obesity Summit opened with a compelling prerecorded video presentation by an expert from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Professor Bill Dietz identified breastfeeding promotion among a small number of ‘best buy’ strategies to combat the obesity pandemic.13 Resolution 3.2 in the Communiqué arising from the Summit was: NSW Health will reinforce breastfeeding policies and services and encourage health professionals to support breastfeeding.14 In the subsequent NSW Health Summit Action Plan, one of the priority actions for supporting parents was ‘to give children a healthy start through breastfeeding’.15 One month after the release of the Action Plan, NSW Health committed substantial funding to a 3-year NSW Health Breastfeeding Project.

The research evidence

Evidence from a synthesis of reviews of interventions to promote and support breastfeeding was available at the start of the Breastfeeding Project.16 This evidence was critical in supporting the decision to pursue a policy-based approach. The synthesis appraised the findings of nine systematic reviews and meta-analyses from established international organisations. Importantly, the evidence was synthesised with the end-user in mind: the information was presented in a highly readable, jargon-free report within a framework for action and several action areas and corresponding intervention points were clearly identified. Decisively, the evidence synthesis concluded that:

there is a substantial body of evidence that provides a sound basis to proceed with evidence-based programs and practices in a number of areas, particularly those areas addressed by mainstream health services. These action areas comprise the organisation of hospital services, and prenatal and postnatal community-based education and support services for women.

The Steering Committee of the NSW Health Breastfeeding Project therefore determined that an evidence-based policy was the optimal approach, with the available funds, for achieving changes to practice.

Linkage and exchange

The synthesis report was produced by the NSW Centre for Public Health Nutrition (CPHN). This centre, located at the University of Sydney, received funding from NSW Health to provide information about the state of food and nutrition in NSW and the evidence base for interventions to improve nutritional health status. The centre was also involved in the production of several other reports and papers relating to the promotion and support of breastfeeding at this time.17,18 The information in these documents was not restricted to the systematic evidence base but considered evidence from other sources, including observational epidemiology (determinants research), as well as summarising the framework for action that had been developed over the previous several years. The researchers participated alongside the policy makers in the Steering Committee and Working Group of the Breastfeeding Project throughout policy development, enabling the evidence to be absorbed into the policy in an iterative manner.

The exchange of information was facilitated by a strong contingent of breastfeeding champions among the key researchers, experts and policy makers involved.

Feasibility to apply the evidence

The feasibility of the proposed evidenced-based approaches was assessed by a range of practitioners. Many representatives of the Steering Committee and Working Group were service providers and user representatives, who had extensive practical and clinical experience in breastfeeding and/or research backgrounds. Considerable expert knowledge, experience and opinion were therefore considered in conjunction with the research evidence.

The feasibility of implementing proposed evidence-based practices was further determined through direct consultation between the Breastfeeding Project Co-ordinator and a sample of 30 senior clinicians and area health service managers. Focus groups were also held with health professionals. This qualitative research identified several attitudinal, organisational, financial and work practice barriers to evidence-based changes to practice. Conversely, the qualitative research identified those evidence-based initiatives and practices that were seen to be feasible and desirable, such as the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative, for which the evidence of effectiveness is particularly strong.19

Discussion

Research evidence was instrumentally used, as opposed to symbolically used, in the development of public health policy and practice guidelines, the NSW Health Breastfeeding Policy.20 Several factors were identified in facilitating the translation of the research evidence into policy.

Timeliness and relevance were key factors affecting the process. The Obesity Summit resulted in breastfeeding becoming relevant and associated with a high priority for the state agency.21 The systematic research evidence also became immediately relevant. Timeliness or relevance is rarely reflected in practice but research findings have greater impact when they are in tune with wider developments of the time.22,23 The strength of the research findings was important at this stage. Syntheses or systematic reviews offer a method that promotes greater levels of confidence in emergent messages and allows the development of confidence in the face of criticisms of a policy.24

Another major facilitator to the process was the linkage and exchange that occurred between the researchers and policy makers. Increased familiarity and contact between the world of research and the world of decision making have been identified as important in reducing the gap between research production and research usage.2,25 The existing structural and professional linkages ensured that the evidence was identified, synthesised and communicated effectively, which often happens on a more ad hoc or indirect basis.26,27 Ongoing collaboration resulted in the development of jointly owned knowledge, which has been identified as important to successful knowledge translation and exchange.20,24

Organisational and structural links also resulted in ongoing, frequent personal contact, a factor that is persistently identified as paramount in research utilisation.21,28–30 The process was further enhanced through the commitment to breastfeeding of the individuals involved. These product champions ensured purposive dissemination of the research evidence.31,32 Evidence itself is a passive resource thus an active approach to the evidence is required to make it accessible, contextualised, usable and implemented.33 In this case, the researchers and policy makers considered the evidence to be strong and were eager to make sure the policy was underpinned by this evidence.

The research evidence was not considered in isolation. Many other types of evidence inform policy and practice and within the Breastfeeding Policy development process, stakeholders provided their own forms of evidence – knowledge, experience, ideas and opinion – to interact with the research evidence in an iterative process.2,34 Broad stakeholder representation can often act against the underpinning of policy with research evidence as each stakeholder brings his or her own experience and ideas to the table. However, the linkages between the researchers, policy makers and other stakeholders, enabled a three-way dialogue to be maintained throughout policy development rather than a linear and unidirectional transfer of information. This dialogue also helped prevent misinterpretation of the evidence, as research findings are easy to abuse, either through selective use, de-contextualisation or misquotation.

The likelihood of policy adoption and implementation success was enhanced through the integration of qualitative evidence from consultation with service managers. Evidence derived from scientific studies is important, but best understood as providing a scientifically plausible framework for intervention, rather than a guide to detailed action at the local level.35 The consultations provided evidence of the feasibility and desirability of policy directions, or of the capacity to act that is often lacking in getting evidence into action.1 The importance of incorporating the views of practitioners, service users and user representatives in the development of evidence-based recommendations in public health has recently been highlighted, also within the domain of breastfeeding promotion and support, in the United Kingdom (UK).36 Ultimately the transparent consultation and iterative exchange of information enabled the integration of the research evidence with the other types of evidence, resulting in an evidence-based product that is likely to be implemented and produce effective results.

This paper has focused on the use of research evidence in the development of the NSW Health Breastfeeding Policy to illustrate the importance of increased investment in policy-relevant public health research, including primary studies as well as research syntheses and reflections. Health providers are being encouraged to turn to research to inform and justify their service delivery decisions, and researchers are increasingly expected to engage policy makers and research consumers in both the construction and dissemination of research.37 However, there is often not enough push from researchers or pull from decision makers to incorporate the research evidence base into policy. Decisions are commonly guided by common sense and experience rather than the formal evidence base.1 Enhanced use of evidence, however, contributes to achieving superior outcomes for the final beneficiaries of knowledge translation, who in return, generate value for money invested in knowledge.27

The funding opportunity for policy-relevant research was an important factor in this case study. NSW Health provided funds to the research centre so had a vested interest in using the research findings. The funding and development of long-term research centres focussing on particular topics, or epistemic communities, are considered to be potentially the strongest ways a health system can take action to increase the possibilities of research being used to inform policy.23,25 Partnering researchers and decision makers has been identified as a priority to facilitate linkage and exchange in Australia.26

Case studies such as this can be limited due to a lack of generalisation of findings. However, the primary factors affecting whether and how research evidence is translated into policy that have been highlighted in the present study are congruent with other findings. Another shortcoming is that the process has been described from the perspective of two main stakeholders; the researcher and the policy maker. Perspectives of others, particularly from those more external to the process, may provide additional insights.

Summary

Effective linkage and exchange between the researchers and the policy makers were crucial to the instrumental use of the research evidence in the development of the NSW Health Breastfeeding Policy. This was underpinned by existing structural and professional links between the researchers and the research users, enabling the research evidence to be identified, synthesised and communicated effectively. The process was strengthened by the individual beliefs of the key players. A range of other factors beyond the research evidence – such as the historical context, the political will and the involvement of stakeholders – contributed to shaping the Breastfeeding Policy.20 Accordingly, translating research knowledge into policy and practice is a more complex and context-sensitive process than simply producing the evidence.38

[1] Bowen S, Zwi A. Pathways to “Evidence-Informed” Policy and Practice: A Framework for Action. PLoS Med 2005; 2(7): e166.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | PubMed | (Cited 22 July 2008.)

[4] Eagar K, Cromwell D, Owen A, Senior K, Gordon R, Green J. Health services research and development in practice: an Australian experience. J Health Serv Res Policy 2003; 8(Suppl. 2): 7–13.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | PubMed | (Cited 22 July 2008.)

[10]

[11]

[12]

[13] Nathan SA, Develin E, Grove N, Zwi AB. An Australian childhood obesity summit: the role of data and evidence in ‘public’ policy making. Aust N Z Health Policy 2005; 2 17.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | CAS | (Cited 22 July 2008.)

[15]

[16]

[17]

[18] Centre for Epidemiology and Research, NSW Department of Health. Breastfeeding and the Public’s Health. NSW Public Health Bull 2005; 16(3–4): 37–61.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | (Cited 22 July 2008.)

[34] Rychetnik L. Evidence-based practice and health promotion. Health Promot J Aust 2003; 14(2): 132–6.

(Cited 22 July 2008.)