Enforcing law on tobacco sales to minors: getting the question and action right

Douglas C. TuttA Health Promotion, Northern Sydney Central Coast Area Health Service

B Email: dtutt@nsccahs.health.nsw.gov.au

NSW Public Health Bulletin 19(12) 208-211 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB08033

Published: 7 January 2009

Abstract

There is a substantial history of health-related law in Australia, but only recently has this included a significant amount of state regulation pertaining to tobacco promotion, sale and public use. The important question is: under what circumstances do regulation and law enforcement work? Rigorous, energetic, long-term local law enforcement on the supply of tobacco to minors demonstrates success in preventing uptake. A model for success combines education, enforcement and publicity; a model used to some effect in alcohol law. Future directions in regulation might include on-the-spot penalties; ensuring the law is simple and has community support; striving for sufficient resources, enthusiasm and skills; and making the tobacco retail industry pay some of the costs of regulating that industry.

Bringing law to bear for public health ends is not new. The first Public Health Act was passed in Britain in 1848, with an independent New South Wales (NSW) Act in 1896. Other NSW laws, like the Abattoir Act of 1850 and the Infectious Diseases Supervision Act of 1881, were necessary to improve health standards.1

Only comparatively recently has law played a significant part in combating tobacco harm with Section 59 of the Public Health Act 1991 of NSW, making sales to under-18-year-olds illegal, although it had been officially illegal to sell to under-16-year-olds for nearly a century.2 Restrictions on marketing and advertising, and on smoking in enclosed public places have become state law since then.2,3

Divergent opinions about the effectiveness of restrictions on selling tobacco to juveniles have been expressed. One view is that it does not reduce teen smoking while proponents counter that ineffective enforcement efforts do not hinder youth-purchasing behaviour, and therefore could not be expected to reduce tobacco consumption.4–7

An example of effective law enforcement

The Gosford-based health promotion unit of Northern Sydney Central Coast Area Health Service has undertaken vigorous activity on cutting retail supply to minors since 1994 when intense education of retailers started. Initially, the enforcement component of this program was undertaken with local police co-operation, but the compliance testing methodology of under-age volunteers attempting purchases has become part of NSW Health practice across the state and public health units now undertake most of the enforcement and prosecution activities.8

Volunteers aged 14–16 years in everyday clothing were rehearsed in asking for a particular product and instructed to be honest if asked by retailers about their age or identification during these controlled purchase operations. Successful prosecutions were the subject of concentrated media activity, including local newspaper front pages and editorials, television current affairs programs’ hidden cameras and an advertised hotline for the public to report law-breaking retailers. Most states were undertaking similar programs by 2000.9

The random testing methodology was confirmed as appropriate in the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal and the Court of Appeal.10,11

The effect on retailer behaviour was quick on the Central Coast (Gosford and Wyong Local Government Areas with a population in excess of 250 000). Within 12 months of starting prosecutions in May 1995, the proportion of retailers selling fell from 30% (which occurred despite months of education) to 8% and continued to further decline throughout the 1990s.12 In 1995, there were six highly publicised, successful prosecutions in this area. The impact of those prosecutions was spread by extensive public relations, creating the perception of a high risk of detection. Ongoing publicity in media and by direct mail is a continuing feature of this work. Although some other health areas did commence action by 1996, none were yet successful in reducing the retailer-selling rate on test to less than 10%, with results varying from 12 to 47%.13

No other special teen smoking intervention was under way during this time in this location. Ordinary school education or exposure to state or national media campaigns continued as usual. A number of local high schools periodically collected and provided data on smoking rates. The first effect was on the youngest and lightest smokers, but as time went on this effect spread across the 12–17 year age range.12 The adolescent smoking rate on the Central Coast in 1993 was similar to that of the rest of the state and nation; however, by 1996 the area had a significantly lower rate than the rest of NSW and, by 1999, only 17.1% of local teens were smoking compared with 25.9% 6 years earlier.12

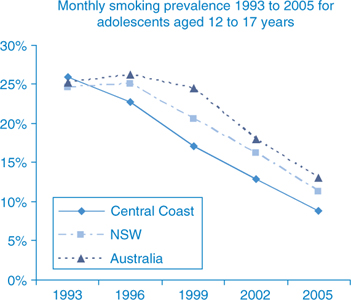

The methodology has continued in the same manner since 1999. The rates of monthly teen smoking compared with state and national rates are shown in Figure 1.

|

The results in Figure 1, which were presented in Northern Sydney Central Coast Area Health Service’s 2007 Performance Review, show the continued difference in local rates from state and national rates. In 2002, eight years after starting action on supply to minors, the Central Coast teen smoking rate remained significantly lower (p < 0.0001) than that of NSW and Australia, even though the reduction in teen smoking in those larger jurisdictions paralleled that of the Central Coast.

The reason is probably because nicotine is an addictive product. Intervention on supply over time becomes intervention in demand, as fewer young people start smoking in the first place. Fewer 13-year-old smokers at one time means fewer addicted 16-year-old tobacco consumers three years later. As time progresses, fewer continuing teen addicts mean fewer smokers can entice others to join them, so the effect continues to compound.

The area between the Central Coast line in Figure 1 and the Australian line represents the total of ‘prevented smokers’ brought about by doing something different from the rest of the country. Of course, other interventions have occurred throughout the nation, notably on the supply side with taxation changes post 1999, and large scale media campaigns on the demand side. But the difference achieved by adopting energetic law enforcement early on is illustrated by Figure 1. That difference equates to nearly 20% fewer teen smokers in those 12 years on the Central Coast than if direct-supply-side law enforcement had not been undertaken when it was.

Other examples of modern health law at work

One of the best examples of saving lives with law in recent decades is roadside random breath testing for alcohol. A quarter of a century ago, more than 40% of deaths on NSW roads were attributed to alcohol.14 The death rate is now reduced to 23%.15 Over 400 lives are saved every year in NSW as a result of the intervention. This outcome has come about by “strengthened legislation and enforcement in conjunction with high profile media and public education activities”.16

Australia’s problems with alcohol attract media and policy attention. Licensed premises are expected to exercise responsible service of alcohol.17 What method works to get these suppliers to practise this responsibility? Unfortunately, it seems education alone is not enough. Just educating bar staff to get them to do the right thing achieves fewer than one in ten acting correctly, but coupling that with enforcement improves that figure nearly eight-fold.18

Determining success

Success in achieving change in tobacco sales to minors, or in road safety and alcohol are underpinned by education, enforcement and publicity. Education is necessary, but it is not sufficient. Enforcement adds to effectiveness. Extensive publicity about enforcement increases the perceived risk of being caught, and also engages a concerned community in knowing that action to address a problem is underway. All of this activity has to be carried out with vigour and skill.

The question to be answered is not whether law and enforcement work. Rather the question is “under what circumstances do they work in achieving public health aims?” The examples above show that education, enforcement and publicity are key components in achieving success.

The Canadian Cancer Society, in reviewing the features of supply efforts targeting tobacco and minors, concluded that a decrease in smoking was brought about by programs that achieved very high rates of retailer compliance and involved comprehensive community-based interventions, well-drafted law, regular checks on compliance, meaningful penalties for offenders and strong community support.19 Such factors may underlie success in various fields of public health law. There is strong community support for action on tobacco, with nearly 90% of people supporting stricter laws and harsher penalties for selling to juveniles.20

The total count of prosecutions under any law can be related to a number of factors. Few prosecutions may indicate that nearly everyone abides by the law; but it could also mean that a law is difficult or complicated to interpret, or that there are few resources, or little enthusiasm or skill for prosecutions. Many of the offences committed around sales, possession or supply of alcohol are dealt with by Penalty Infringement Notices (on-the-spot fines), increasing the ease of prosecution. The implementation of Penalty Infringement Notices is an important possible future direction for tobacco law.

Another question that might arise is whether scarce resources would be better spent in other ways. Estimating staff time and goods and services expenditure invested through the 1990s in all the activities associated with this work on the Central Coast, and dividing this by the numbers of 16-year-old ‘prevented smokers’ (those who would have been expected to be smoking without the reduction observed), arrives at a cost of only $100–200 to create a non-smoker this way, which is 5–10 times more cost effective than using nicotine replacement therapy to wean an adult smoker off nicotine (author’s personal data). One cost is a public expenditure (enforcing law); the other is private (treating your own addiction).

This is an endeavour where we can get good gain for our money, but there could even be better value for our existing public dollar if some of the costs of policing a private tobacco industry were recovered from the industry itself, perhaps using some form of annual retailer registration fee. The potential to lose such a licence for infringements could be an added deterrent to illegal behaviour.

The history of law enforcement undertaken for health benefit going back to the Public Health Act of 1848 suggests a long held belief that it is effective in improving health. Unease about law enforcement can arise within health agencies because most people employed within health provide healing and individual comfort. This focus on warmth and helping is the basis of professional, non-judgmental clinical services. At the other end of the personal interaction scale is zero tolerance policing, which some claim has cleaned up New York’s streets.21 This approach aims to inflict pain on those prosecuted and to create nervousness in many who potentially could be.

Public health law enforcement may seem distasteful or old fashioned in an era of individual choice and high technology treatments. However, it still represents good value when we want to bring about large-scale community change. Investing in improving the legal and prosecution skills of our workforce will pay dividends.

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4] Ling PM, Landman A, Glantz SA. It is time to abandon youth access tobacco programmes. Tob Control 2002; 11 3–6.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | PubMed | CAS | (Cited 11 July 2008.)

[16]

[17]

[18] McKnight AJ, Streff FM. The effect of enforcement upon service of alcohol to intoxicated patrons of bars and restaurants. Accid Anal Prev 1994; 26 79–88.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | PubMed | CAS | (Cited 8 July 2008.)