Urbanism, climate change and health: systems approaches to governance

Anthony G. Capon A D , Emma S. Synnott B and Sue Holliday CA National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Australian National University

B Arup (global firm of designers, engineers, planners and business consultants)

C Strategies for Change (urban strategy consultancy)

D Corresponding author. Email: tony.capon@anu.edu.au

NSW Public Health Bulletin 20(2) 24-28 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB08059

Published: 25 February 2009

Abstract

Effective action on climate change health impacts and vulnerability will require systems approaches and integrated policy and planning responses from a range of government agencies. Similar responses are needed to address other complex problems, such as the obesity epidemic. Local government, with its focus on the governance of place, will have a key role in responding to these convergent agendas. Industry can also be part of the solution – indeed it must be, because it has a lead role in relevant sectors. Understanding the co-benefits for health of climate mitigation actions will strengthen the case for early action. There is a need for improved decision support tools to inform urban governance. These tools should be based on a systems approach and should incorporate a spatial perspective.

The challenge

This paper argues for a systems oriented governance model to integrate responses to health and climate change in an urban context. Health impacts of climate change arise from direct and indirect pathways, including extreme weather, changing patterns of infectious disease, effects on fresh water supplies and food yields, loss of livelihoods, displacement of vulnerable populations and impaired functioning of ecosystems.1 Regions and communities will experience differing impacts of climate change, based on varying exposure and sensitivity. Vulnerability to health impacts is also a consequence of adaptive capacity.2

A recent report from the United Kingdom (UK) on tackling the obesity epidemic highlights similarities with tackling climate change – ‘both need whole societal change with cross governmental action and long-term commitment’.3 Importantly, the underlying causes of anthropogenic climate change are inextricably linked with the underlying causes of the obesity epidemic.

Our modern way of life is changing the climate and making us sick.4 Addressing the underlying causes of these related challenges requires a convergent approach where we recognise a common policy locus in the places in which we live. This includes organising our response on a spatial basis and improved urban governance. Traditional approaches to health and urban planning tend not to speak the same language and there is a need to conceptually align their agendas, developing integrated approaches to the planning, development and management of the places in which we live – to ensure these are healthy and sustainable places.

Governance, systems thinking and virtuous cycles

Governance refers to processes to ensure the effective management of a project, organisation or system. In Australia, cities and towns – the places where most of us now live; and places that can foster economic development – are governed through a multitude of structures, regulations and policies. Now, more than ever before, we require a common approach to the city, as the focus of sustainable living in its widest sense. Our governments (local, state and national) should lead on the governance of towns and cities; and they should do so in partnerships with industry and the wider community. The challenge of achieving integrated health and sustainability outcomes is how to embed this way of thinking into the daily business of governance, whether this is a strategic policy or a spatial project.

There are lessons for Australia from the approach to sustainability governance taken in the UK. Mechanisms include formal sustainability commissions with statutory reporting responsibilities; sustainable development frameworks to guide strategic and spatial policy at national, regional and local levels; independent assurance of sustainability goals; and statutory requirements to consider sustainability in policy and planning decisions. The London experience is instructive. The Greater London Authority Act requires the Mayor to meet a statutory duty to ‘promote health, equality of opportunity and sustainable development’. The London Sustainable Development Commission was established in 2002 to advise the Mayor on developing the city as an exemplary sustainable city and to assist in fulfilling the Mayor’s statutory duty. The Commission designed an integrative sustainable development framework by which it could appraise decisions and drive policy development; taking decision-makers beyond an approach that simply divided policy initiatives into the usual social, environmental and economic silos.5 This framework is based on the concept of ‘virtuous cycles thinking’ where co-benefits are identified and actively pursued (Figure 1).6,7

|

Embedding sustainability into decision-making can be significantly bolstered by formal governance structures that incorporate external reporting. The UK Sustainable Development Commission now reports annually on progress of the government estate in meeting its sustainability targets, including its commitment to be carbon neutral by 2012.8

Whether planning for the aged, the ageing or for the next generation, the way we conceive and design our cities will influence the ability of the population to choose the way it lives. Rather than thinking about zonings and land uses, a people-centred approach to planning will lead to different outcomes from those we have today. Starting with a premise of reshaping the city around how an individual and their family use the city for daily needs, a different solution emerges. If a healthy way of life is at the core of that thinking, then a more self-contained model of neighbourhood and region is the outcome. Walking to school, the local shops, accessing public transport easily for the journey to work and for daily needs and providing cycleways to local recreation and community activities are some design requirements for a healthy city. To achieve this end, a more integrated approach to planning is needed – considering environment, transportation, work and people. The approach should consider how people will inhabit their place, and what their habits (behaviours) mean for their health and wellbeing, and for the health of the environment.

The current situation

There are myriad sustainable urbanism demonstration projects in Australia and abroad, both greenfield and retro-fit. Some examples include: Christie Walk, an eco-housing development in Adelaide; eco-towns and cities planned in the UK, China and the Middle East; and Samso, an island in Denmark, which is currently the largest carbon-neutral settlement in the world. An important lesson from Samso is that people want to be involved in decision-making and innovation; something oft-cited as beneficial, but rarely achieved.

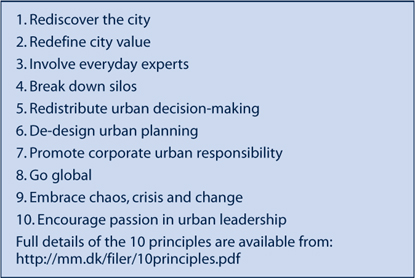

The Copenhagen Agenda for Sustainable Cities is a Danish initiative in advance of the United Nations’ Climate Conference later in 2009. The Agenda advocates improved city planning, development and management as a strategy for tackling climate change and other pressing global challenges, such as poverty and epidemic chronic disease. The Scandinavian thinktank, Monday Morning, canvassed 50 urban experts and identified 10 principles for sustainable city governance (Box 1). In moving forward with this initiative, it will again be important to ensure integrative approaches to achieve sustainable and healthy cities.

|

The Western Sydney Regional Organisation of Councils has recently developed an Agenda for Sustainability and Wellbeing, which argues that social, environmental, cultural and economic issues need to be considered together in an ecological way. This agenda arises from a view that cities are ‘human ecological systems’ that are supported by, and integrated with, ‘natural ecological systems’. The sustainability of the city, and the health and wellbeing of the population, are seen as a consequence of interaction between these ecological systems. The agenda seeks to widen the focus of sustainability from individual behaviour change (such as reducing household water and energy use) to structural changes in the places in which people socialise, live and work.

Healthy Spaces and Places is a project that aims to promote the development of built environments, which facilitate lifelong active living, and promote good health outcomes, for all Australians. It is an initiative of the Planning Institute of Australia, in partnership with the National Heart Foundation and the Australian Local Government Association, and with the support of the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. It builds on the Healthy by Design initiative of Institute’s Victorian Division.9

Health impact assessment methods have been used to assess impacts and vulnerability to climate change.2 This methodology is a useful decision support tool for policy and planning responses to climate change. An important challenge is to ensure that such assessments are informed by a systems perspective.

Suggested actions

First, there is a case for a paradigm shift in current sustainability discourse. The three pillars of sustainability – environmental, social and economic (often called the triple-bottom-line) – are means rather than ends.10 Environmental, social and economic circumstances are all important determinants of human life experience and, ultimately, physical and mental health and wellbeing. Health should therefore be considered a primary outcome in all sustainability policy and planning.

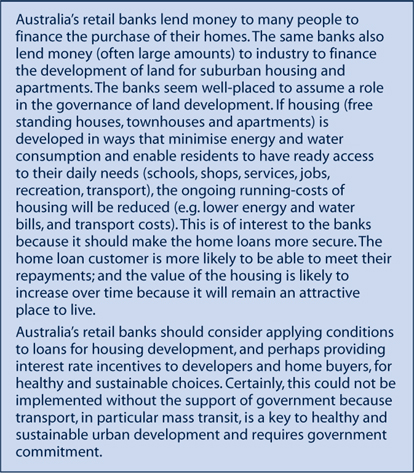

Second, there is a need to apply what we already know about human-environment interactions to the planning, development and management of the places in which we live. This, and further research, should be informed by a systems understanding of health and wellbeing and should identify roles and responsibilities for industry (Box 2) and acknowledge the contribution of civil society.3

|

Third, there is a need for workforce development and capacity building. Professional bodies, such as the Planning Institute of Australia, the Public Health Association of Australia and the Australasian Faculty of Public Health Medicine are responding to this challenge. The University of New South Wales’ teaching program in Healthy Urban Planning provides opportunities for inter-professional learning for health and planning students.11 Planning and public health courses should embrace systems methods and ensure future professionals are equipped to deal with emerging challenges.

Finally, there is a need for improved decision support tools, for example, audit tools that incorporate both a systems perspective and a spatial focus and acknowledge the need for effective governance approaches. These can build on existing methods and should accommodate quantitative and qualitative information (Table 1).

|

Meeting the challenge

Climate change and obesity have been characterised as ‘wicked policy problems’ – problems that cannot be successfully treated with traditional linear, analytical approaches.12,13 That said, we must not be overwhelmed by the complexity of these challenges. Systems understanding can help us navigate a path through the complexity. Without such an approach there appears to be no clear governance strategy for addressing the spatial and policy intersection between the structure of our cities, trends in health outcomes and the carbon intensity of our way of life. We have to be prepared to make decisions and, in doing so, allow ourselves to make mistakes. Provided we learn as we go, we will make progress.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Liam Ryan for assistance with Figure 1. Anthony Capon is partly supported by funding from an NHMRC Australia Fellowship award to Professor AJ McMichael.

[1] McMichael AJ, Friel S, Nyong A, Corvalan C. Global environmental change and health: impacts, inequalities and the health sector. BMJ 2008; 336 191–4.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | CAS | PubMed | (Cited 26 October 2008.)

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6] Stott R. Implications for health in a low carbon (Contract and Converge) world. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006; 60 828.

| PubMed | (Cited 26 October 2008.)

[9] Sutherland E, Carlisle R. Healthy by Design: an innovative planning tool for the development of safe, accessible and attractive environments. N S W Public Health Bull 2007; 18 228–31.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | PubMed | (Cited 26 October 2008.)

[12]

[13] Rittel H, Webber M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci 1973; 4 155–69.

| Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar |