Waterborne diseases among Aboriginal people

Patricia Morton A , Gillian Barlow B and Ross Bailie CA NSW Public Health Officer Training Program, NSW Department of Health

B Department of Aboriginal Affairs

C Menzies School of Health Research

NSW Public Health Bulletin 21(8) 183-184 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB09020

Published: 27 September 2010

Aboriginal people in many communities in New South Wales (NSW) have, until now, not enjoyed the same access to water and sewerage services as the rest of the NSW population. Evidence from international studies shows that lack of these services leads to poorer health.1

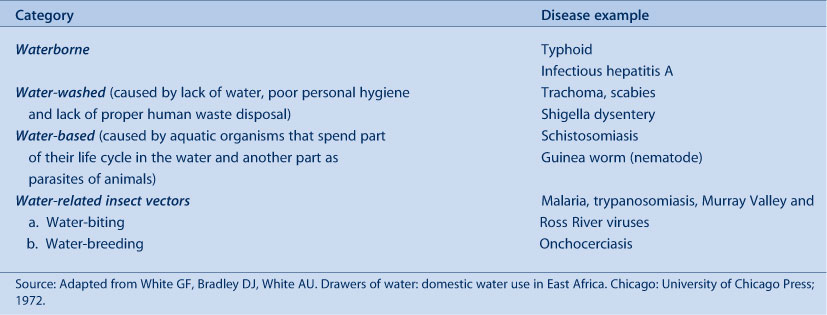

Adequate quality and quantity of water are essential for drinking, food preparation and cooking, washing, waste removal, cultivation and recreation and, therefore, for health. A study of the global burden of disease found that poor water supply, sanitation, personal and domestic hygiene were responsible for 5.3% of total deaths and 6.8% of total disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in 1990.2 There are a number of communicable diseases that result from poor water quality and quantity and they can be classified according to transmission route (Table 1).3

|

Since Aboriginality is poorly reported on deaths data by health care workers (identification is currently estimated at 76.6%)4 it is difficult to determine the number of Aboriginal deaths from the diseases caused by poor water quality and quantity in NSW. However, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare has found that Aboriginal infants in Australia are 7.9 times more likely to die of infectious and parasitic diseases (which would include waterborne diseases) than non-Aboriginal infants. Furthermore, Aboriginal children aged 1–14 years are five times more likely to suffer from these diseases than non-Aboriginal children.5

After NSW became a British colony, Aboriginal people were made to live together in locations on the edges of, or remote from, towns. These communities became known as ‘reserves’ and, after the Aboriginal Land Rights Act was enacted in 1983, became the responsibility of the Local Aboriginal Land Councils. The Local Aboriginal Land Councils were responsible for all services on the reserves including maintenance of the water and sewerage infrastructure. Although the Act was intended as an act of reconciliation, the newly created Local Aboriginal Land Councils were given responsibilities for which they were ill-prepared, including the maintenance of water sewerage infrastructure.

With the evidence that Aboriginal people are more likely to suffer from infectious and parasitic diseases and that water quality in certain Aboriginal communities in NSW is often inadequate, a broad alliance of NSW Government departments and non-government organisations prepared a case for the NSW Government to address the issue. In 2008, the NSW Government committed $250 million of funding over 25 years for the upgrade, maintenance and operation of the water and sewerage infrastructure on specific Aboriginal communities. This program is currently being implemented and will require ongoing participation from the NSW Department of Health and regional public health units to ensure the interests of the communities are considered.

[1] Prüss A, Kay D, Fewtrell L, Bartram J. Estimating the burden of disease from water, sanitation, and hygiene at a global level. Environ Health Perspect 2002; 110(5): 537–42.

| PubMed | (Cited 31 May 2010.)

[5]