Communicable Diseases Report, NSW, September and October 2009

Communicable Diseases Branch,NSW Department of Health

NSW Public Health Bulletin 20(12) 199-204 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB09045

Published: 4 February 2010

Abstract

For updated information, including data and facts on specific diseases, visit www.health.nsw.gov.au and click on Public Health then Infectious Diseases, or access the site directly at: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/publichealth/infectious/index.asp.

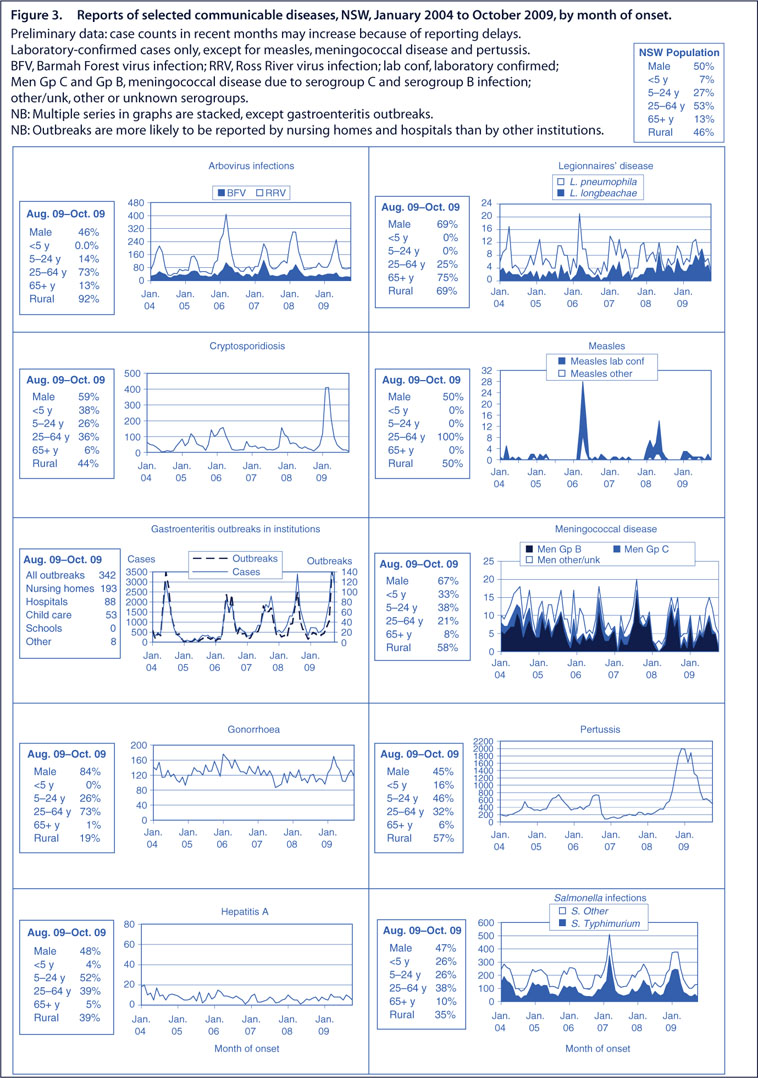

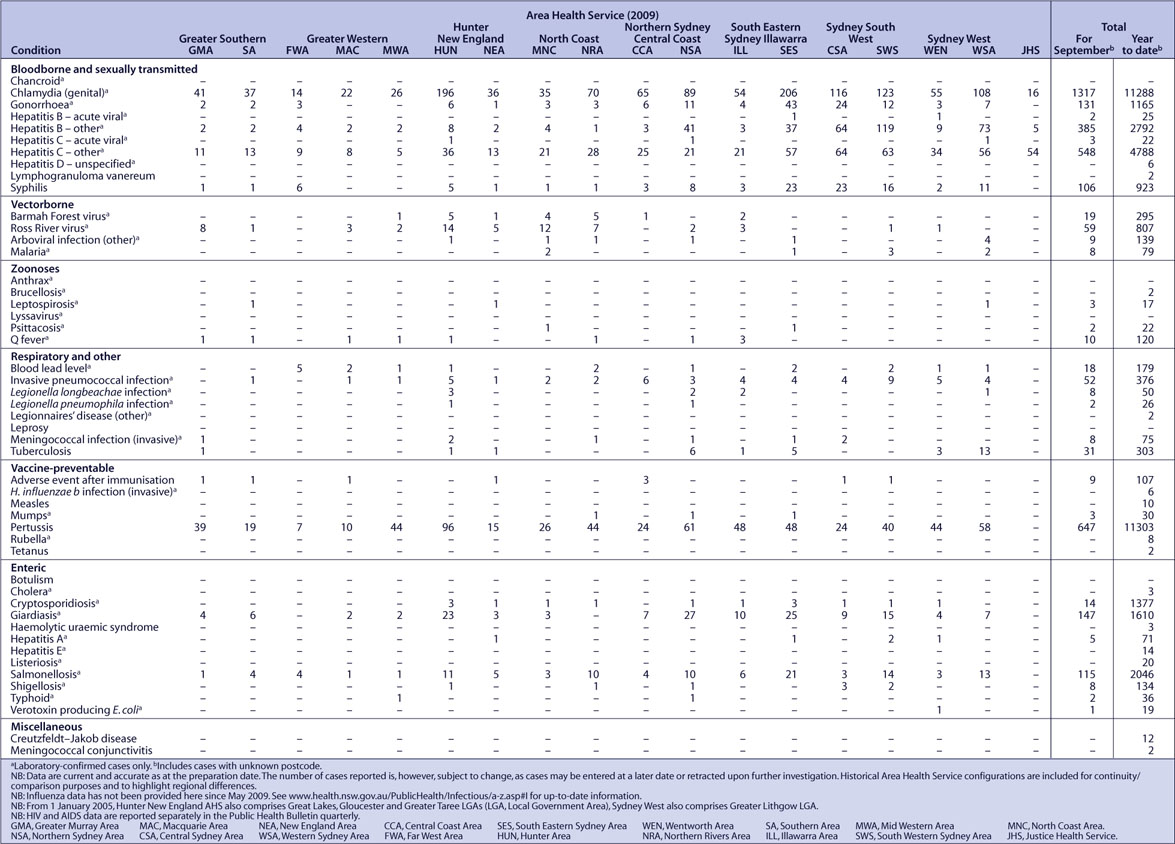

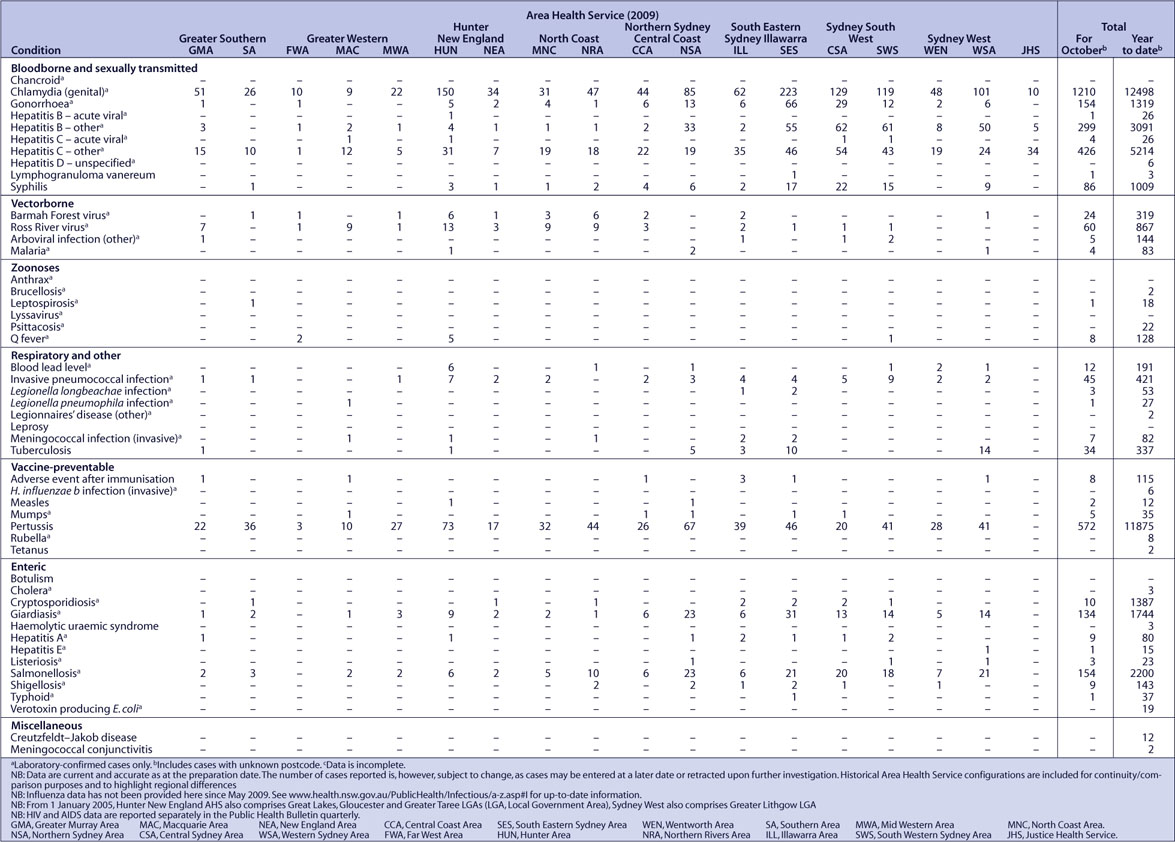

Figure 3 and Tables 1 and 2 show reports of communicable diseases received through to the end of October 2009 in New South Wales (NSW).

Potential exposures to rabies and Australian bat lyssavirus infection

Lyssaviruses are a group of viruses that include rabies and Australian bat lyssavirus (ABLV). Rabies is an infection of mammals that is transmitted through biting or scratching. It occurs in many parts of the world, but not in Australia. Infection with rabies can sicken and kill the affected mammal, and infection in humans is usually fatal.

ABLV is a virus that is related to, but slightly different from, rabies. Humans are rarely infected: only two cases of human infection with ABLV have been recorded, both in Queensland in the mid-1990s and both were fatal.

Overseas, mammals that carry rabies include: bats, dogs, cats, raccoons, skunks, monkeys, and other mammals that bite and scratch. Australian mammals do not carry rabies. In Australia, only bats – both the larger flying foxes (or fruit bats) and the smaller insectivorous (or micro) bats – have been found to carry ABLV.

People may be at risk of rabies while travelling overseas if they come into contact with wild mammals or with domestic mammals that bite and scratch that have not been vaccinated against rabies. In Australia, people who handle bats are at risk of ABLV infection. No-one should attempt to handle bats unless they have been vaccinated against rabies and are trained in – and use – the proper personal protective equipment. If a sick or injured bat is found, the local wildlife rescue service should be contacted. Bites or scratches from Australian bats (or mammals overseas) require urgent treatment. For more information, see: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/factsheets/infectious/rabiesbatinfection.html.

Anthrax

Anthrax was recently reported on a farm in southern NSW following the sudden death of several sheep. The public health investigation revealed four human contacts, all of whom remain well. Of these, one person had repeated direct contact with affected carcasses and received a 10-day course of ciprofloxacin for chemoprophylaxis.

Anthrax is an acute infectious bacterial disease caused by a toxin released by the anthrax bacterium (Bacillus anthracis). The disease can affect many species of domestic and wild animals and humans. The NSW Stock Diseases Act 1923 requires that animals with suspected anthrax infection be notified immediately to the NSW Department of Industry and Investment (I & I NSW) via the local Livestock Health and Pest Authority.

Anthrax occasionally appears in livestock (mainly sheep and cattle) from properties located in the ‘anthrax belt’, a wide region, which extends across central NSW and into Victoria. Because anthrax spores survive in soil for decades, unimmunised livestock in these areas can develop the infection when they graze. I & I NSW can provide advice about anthrax vaccination of livestock in affected areas.

Once anthrax infection is confirmed on a property, the regional Veterinary Officer notifies local public health unit staff who then identify and manage health risks to any human contacts.

Anthrax infection in humans is extremely rare in NSW. Humans are at risk when they come into close contact with the body fluids or tissues of an animal that has died from anthrax. Cutaneous anthrax is the most common form of anthrax infection seen in NSW. This appears as an itchy blister or lump that enlarges and becomes ulcerated, leaving an area of black, dead tissue in the middle of the lesion. The infection is treated with antibiotics. For more information, see: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/factsheets/infectious/anthrax.html, and http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/agriculture/livestock/health/humans/anthrax.

Measles

Two unrelated cases of measles were reported during September and October.

The first case, a woman aged in her 30s who had recently returned from travelling in South Africa, was reported from the Northern Sydney Central Coast Area Health Service. The case was symptomatic during the flight to Australia but was not notified until more than a week after her arrival in Sydney. An outbreak of measles has been reported in South Africa in recent months (http://www.promedmail.org/pls/otn/f?p=2400:1202:50943::NO::F2400_P1202_CHECK_DISPLAY,F2400_P1202_PUB_MAIL_ID:X,79609).

Measles can be prevented if measles-containing vaccine is given to a susceptible person within 3 days of their exposure to an infectious case, or if normal human immunoglobulin is given within 7 days of their exposure. In this case, as more than 7 days had passed since the flight, post-exposure prophylaxis would not have been helpful for potentially susceptible contacts. However, passengers thought to be at risk of infection (i.e. those born in Australia since 1966, many of whom have not been exposed to measles infection or who would have received only one dose of Measles-Mumps-Rubella vaccine) sitting in the two rows surrounding the case were contacted by public health units. These passengers were provided with information on the symptoms of measles and how to prevent further spread. No secondary cases were identified.

The second case was reported in a student aged in his 30s from the Hunter New England Area Health Service. The case reported no recent travel, and the source of infection remains unknown. Contacts were identified at a university and at two hospitals in the area. Due to delays in confirmation, people who were in contact with the case were provided with information about measles and how to prevent further spread. No secondary cases were identified.

There have been 12 cases of measles reported in NSW in 2009 to date compared with 39 for the same period in 2008. In Australia, most cases are reported in either travellers who have acquired the infection in countries where measles is endemic, or in their contacts. Measles vaccine is routinely given to infants at 12 months and 4 years and this confers long-lasting immunity.

Meningococcal disease

Fourteen cases of meningococcal disease were reported during September and October. There have been 79 cases of meningococcal disease in NSW in 2009, including four deaths. For the corresponding period in 2008, there were 69 cases reported and three deaths.

There are several serogroups responsible for meningococcal disease infection. A free vaccine for meningococcal C disease was added to the National Immunisation Program Schedule in 2003 and is routinely given to infants at 12 months of age. Consequently, serogroup C meningococcal disease is now mainly seen in adults and in unimmunised children. In NSW, the most common is serogroup B for which there is no vaccine.

Hepatitis A

Fourteen cases of hepatitis A were reported in NSW in September and October. Of these, 10 were likely acquired overseas, and the remaining four in Australia. Of these four, two reported consuming semi-dried tomatoes 2–6 weeks before the onset of illness, one reported travel to Victoria, and one acquired the infection from a partner who had travelled overseas. Public health experts continue to investigate the cause of the outbreak of hepatitis A linked to semi-dried tomatoes in Victoria (http://hnb.dhs.vic.gov.au/web/pubaff/medrel.nsf/LinkView/D8172AF758EDF26ECA25764A002574DE?OpenDocument).

Hepatitis A virus infection is one of the causes of inflammation of the liver (or ‘hepatitis’). Symptoms include feeling unwell, aches and pains, fever, nausea, lack of appetite, abdominal discomfort, followed by dark urine, pale stools and jaundice (yellowing of the eyeballs and skin). Illness usually lasts 1–3 weeks (although some symptoms can last longer) and is almost always followed by complete recovery. Hepatitis A is usually transmitted when virus from an infected person is swallowed by another person through: eating contaminated food; drinking contaminated water; handling nappies, linen and towels soiled with the faeces of an infectious person; or after direct contact (including sexual contact) with a person in the infectious stage of the illness.

Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza

In September and October 2009, influenza activity in NSW – as measured by the number of people who presented to emergency departments (EDs) with influenza-like illness (ILI) and the number of patients who tested positive for H1N1 at diagnostic laboratories – continued to decline after peaking in July. In summary, there were:

-

declines in presentations to EDs for ILI, although presentations were higher than for the same period last year

-

52 cases of laboratory-confirmed influenza (including 42 of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza) reported in September and 12 (including 11 of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza) in October

-

three deaths notified in association with confirmed pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza

-

28 admissions to hospital following presentation to EDs with ILI in September and 15 in October.

For a more detailed report on respiratory activity in NSW see: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/publichealth/Infectious/reports/influenza_02112009.asp

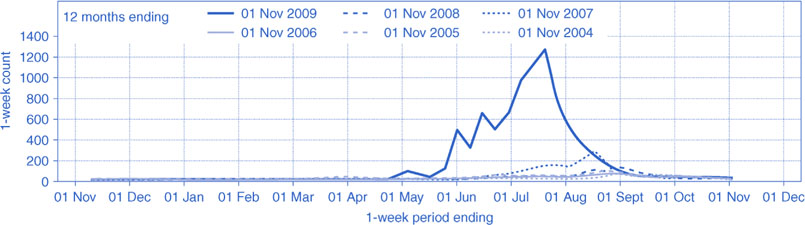

Gastroenteritis outbreaks

During September and October, there were 265 outbreaks of gastroenteritis in institutions in NSW reported, including 155 outbreaks in aged-care facilities, 62 in hospital wards, 40 in child-care centres and eight in other facilities. All outbreaks appear to have been caused by viruses and spread from one person to another. Clostridium difficile infection may also have played a role in one outbreak. In winter months, there is an increase in the number of outbreaks of viral gastroenteritis reported in institutions in NSW (Figure 2).

|

|

|