Navigating public health chemicals policy in Australia: a policy maker’s and practitioner’s guide

Adam Capon A B C , Wayne Smith B and James A. Gillespie AA Menzies Centre for Health Policy, The University of Sydney

B Environmental Health Branch, Health Protection NSW

C Corresponding author. Email: adam.capon@doh.health.nsw.gov.au

NSW Public Health Bulletin 23(12) 217-227 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB12110

Published: 15 March 2012

Abstract

Chemicals are ubiquitous in everyday life. Environmental health practitioners rely on a complex web of regulators and policy bodies to ensure the protection of public health, yet few understand the full extent of this web. A lack of understanding can hamper public health response and impede policy development. In this paper we map the public health chemicals policy landscape in Australia and conclude that an understanding of this system is essential for effective environmental health responses and policy development.

There are over 39 000 chemicals on the world market today,1 with the potential for this number to increase significantly through new manufacturing techniques such as nanotechnologies. These chemicals are widespread, occurring in everything from the food we eat, to the clothes we wear, to the cars we drive. The regulation of an item that permeates through every facet of our lives is by its nature complex. This complexity is difficult to navigate, particularly when public health practitioners are faced with an adverse health effect from a chemical product.2 Knowledge of the range of chemical regulators and policy bodies allows for proper engagement with the system.

In an attempt to prevent adverse health effects occurring governments produce policies designed to minimise the exposure of the population to chemicals. Environmental health practitioners are often called upon to design or review these policies for the protection of the public’s health, but without having a fundamental understanding of the regulators who can enact this protection it is difficult to ensure the policy developed will be effective and functional.

The following describes the complex web of regulators and policy makers in Australia that underpins the development of comprehensive, well-informed chemicals policy and appropriate practitioner response.

Making the chemical policy web

The current fragmented system of chemical regulation in Australia grew out of Australian federalism. In 1901 the Australian Constitution assigned a limited list of powers to the Commonwealth Government. The regulation of chemicals was not among them, leading to each state developing a unique approach to chemical issues and fragmenting chemical issues across different portfolios.3

The rise of the environmental movement in the 1960s and 1970s saw the establishment of the first state-based environmental protection agencies and national ministerial councils. Strong nationalisation of chemical policy issues in the form of targeted ministerial councils and national regulators only emerged in the 1990s out of the Hawke Government’s ‘New Federalism’ and attempts to develop national regulatory strategies through the Council of Australian Governments (COAG). This period saw the establishment of national regulators in agricultural and veterinary medicines, therapeutic goods, food, industrial chemicals, as well as various other agencies and ministerial councils. However, since much of the legislative power to implement and monitor controls rests with the states and territories, these agencies were limited in their ability to impose national uniformity of policy.

A third wave of reform began in 2005 with the then Prime Minister’s direction to reduce unnecessary regulatory burden on business.4 COAG set about establishing a high-level taskforce to develop an integrated, national chemicals policy. The main aim of these reforms was to develop uniform regulation between states on chemical issues. These reforms are ongoing and while they are designed to develop uniformity within areas of chemical regulation (such as therapeutics), there is limited development of uniformity between areas of chemical regulation.

Current structure of chemicals policy

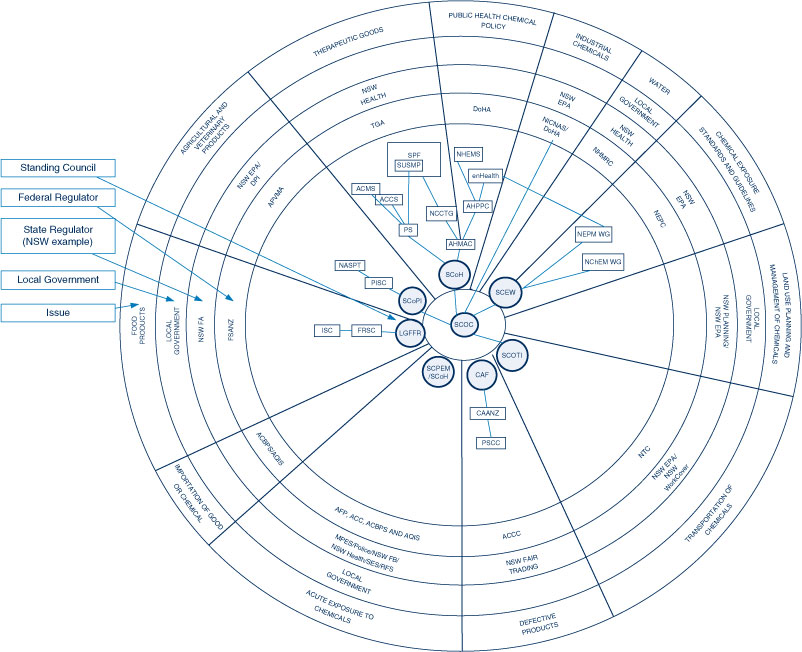

The current structure of public health chemicals policy in Australia remains highly fragmented with 12 distinct segments (Figure 1). Some correspond to industrial sectors: therapeutic goods, agricultural and veterinary products, food products and a general category of industrial chemicals. Others developed out of responses to distinct regulatory problems: defective products, exposure standards, acute exposure, transportation of chemicals, land use planning, water, importation and public health policy.

|

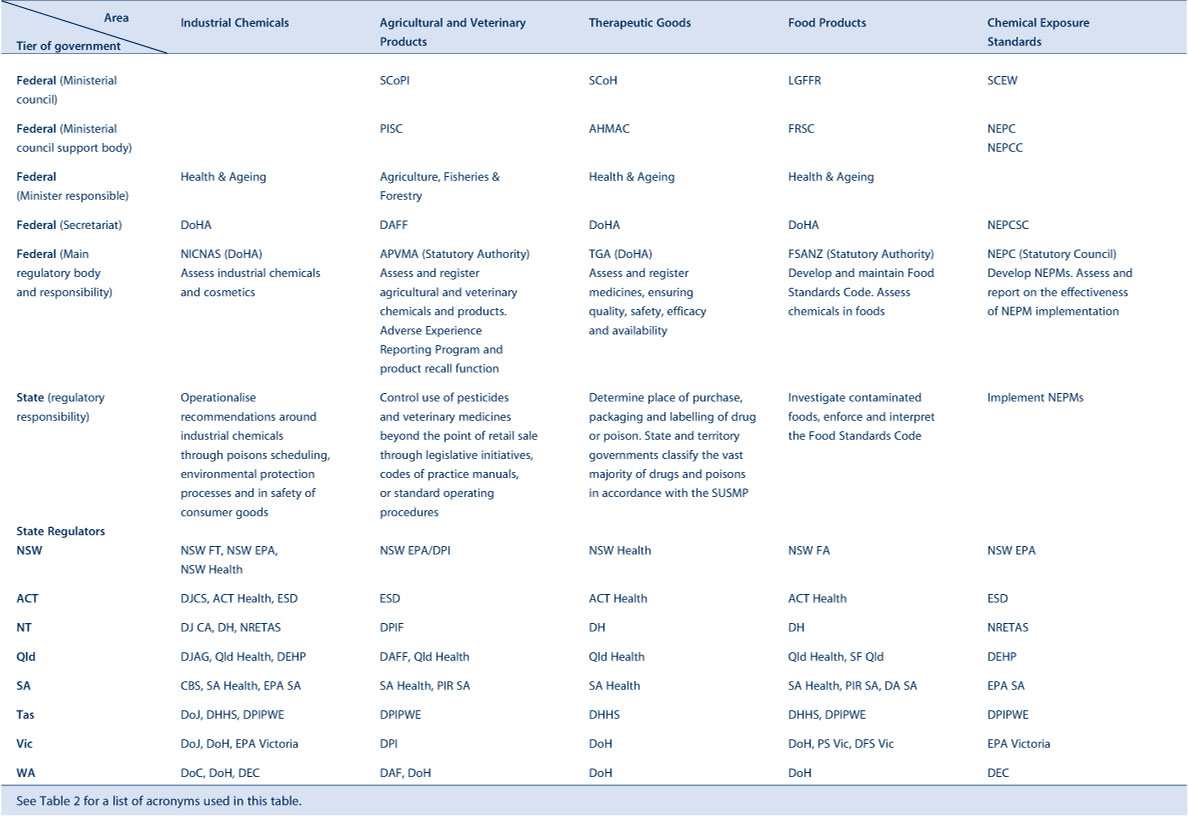

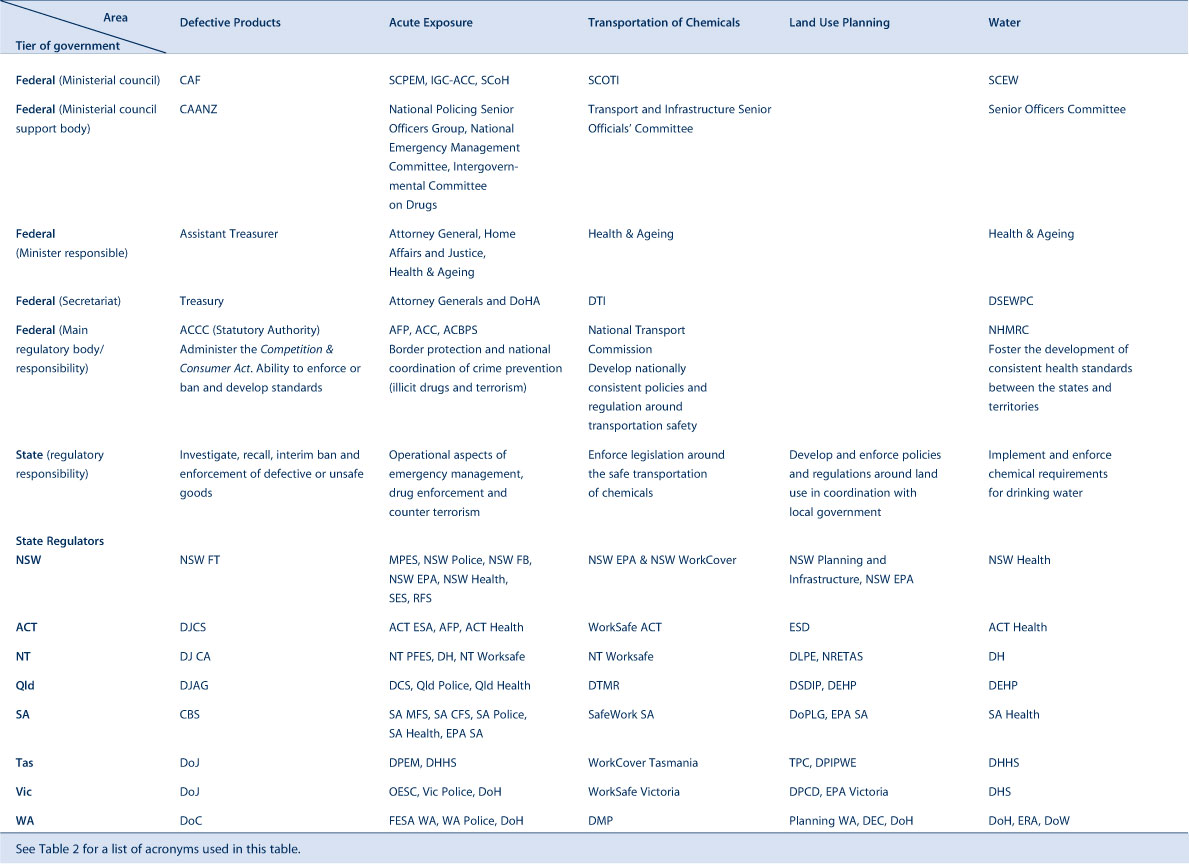

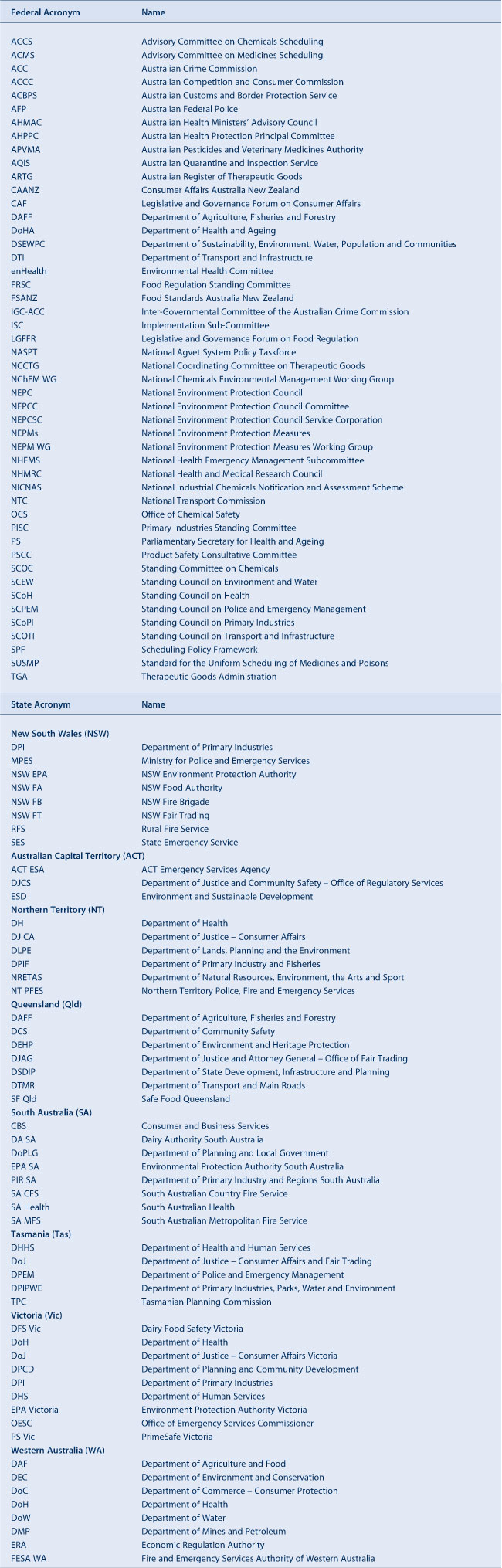

Tables 1a and 1b stratify 10 of these areas with their agencies and functions at federal and state level. Table 2 provides a list of acronyms used in this paper.

|

|

|

Chemicals policy in Australia has the Standing Committee on Chemicals (SCOC) at its centre (Figure 1). The SCOC consists of representatives from the various standing councils and federal government agencies. It heads a regulatory hierarchy in each segment led by a standing council of federal and state ministers, which works towards more uniform national policy responses.5 These standing councils are generally supported by committees of senior state and federal bureaucrats and any federal government agencies with regulatory responsibility for the area of chemicals policy in question.

Segmented areas of chemicals regulation and policy

Therapeutic products, emergency management and public health chemical policy: the Standing Council on Health and the Therapeutic Goods Administration

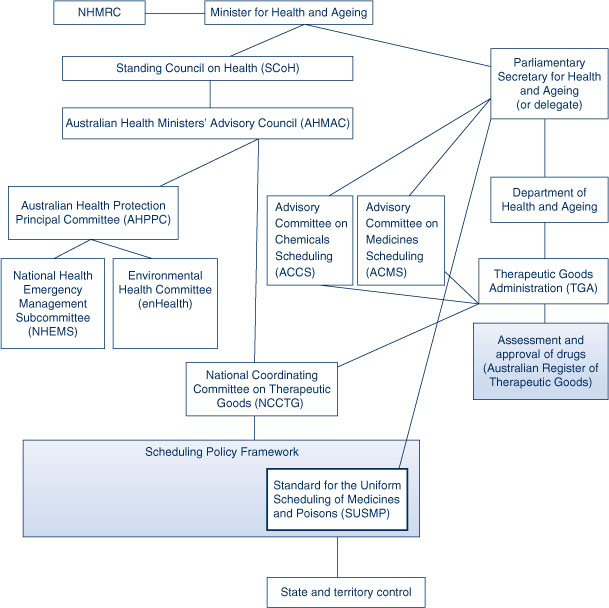

The ministerial Standing Council on Health (SCoH) provides overall leadership in the regulation of therapeutic goods and public health issues arising from chemicals (Figure 2), drawing advice from the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (AHMAC). For public health policy the AHMAC take advice from six key subcommittees, of which the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) is the most important in terms of chemicals policy. The AHPPC includes federal and state Chief Medical/Health Officers, with representatives from other technical agencies, and provides advice and makes recommendations regarding environmental health policy and environmental threats and emergencies. It draws this advice from the Environmental Health Committee (enHealth) and the National Health Emergency Management Subcommittee (NHEMS).

|

The National Coordinating Committee on Therapeutic Goods (NCCTG), a sub-committee of AHMAC, has overall responsibility for the Scheduling Policy Framework (SPF), a framework that sets out the national system for applying access restrictions on all poisons (including therapeutics) that pose a potential risk to public health and safety.6 Chemicals are ‘scheduled’ according to the degree of risk and the level of control required to protect consumers. A chemical may be referred to one of two committees to determine at what level it is to be scheduled – the Advisory Committee on Medicines Scheduling (ACMS) and the Advisory Committee on Chemicals Scheduling (ACCS). These committees provide advice to the Commonwealth Parliamentary Secretary for Health and Ageing (PS) (or their delegate), who has the final decision regarding the scheduling of the chemical in question;7 this decision will be made after extensive public consultation. A record of this decision is included in the Standard for the Uniform Scheduling of Medicines and Poisons (SUSMP). Each state then develops its own regulations around purchasing, packaging, labelling and enforcement of the SUSMP.

Products for which therapeutic claims are made are regulated by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) and associated state government agencies. The TGA assesses therapeutic goods for listing or registration on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG), undertakes monitoring activities, and provides technical and administrative support to those committees involved in the scheduling of chemicals.

Agricultural and veterinary products: the Standing Council on Primary Industries and the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority

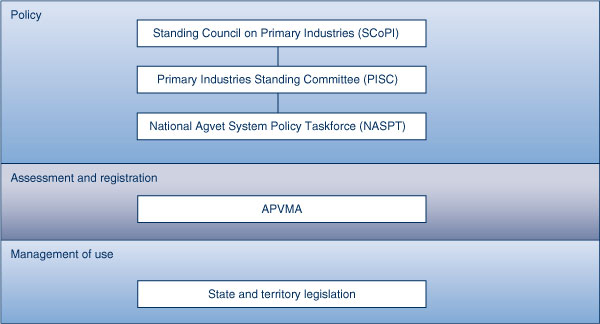

The regulation of agricultural and veterinary chemicals follows a similar model (Figure 3) with the ministerial Standing Council on Primary Industries (SCoPI) developing policy and direction for the national regulator, the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA).

The SCoPI is supported by the Primary Industries Standing Committee (PISC). Sitting under the PISC is the National Agvet System Policy Taskforce (NASPT) which is tasked with developing a new national framework for the regulation of agricultural and veterinary chemicals.

The APVMA is the regulator responsible for the assessment and registration of agricultural and veterinary chemical products in Australia. Through the National Registration Scheme the APVMA registers and regulates the manufacture and supply of all pesticides and veterinary medicines used in Australia, up to the point of retail sale. The APVMA also assesses agricultural and veterinary chemicals or products for potential impacts on human health, the environment, trade and efficacy.

The APVMA contracts the Office of Chemical Safety (OCS) in the Department of Health and Ageing to undertake public health assessments. As part of this assessment, the product may also be classified as a poison, at which point the product is referred to either the ACMS or ACCS for scheduling. The APVMA will set Maximum Residual Levels. These are the highest concentrations of agricultural and veterinary chemical residues permitted in food or animal feed and are set ensuring consumption of foods with these residues does not constitute an undue hazard to human health. The APVMA approves the labelling of a product. They also have the power to refuse an application if they are not satisfied that the product will not be harmful to human beings, and may also put conditions on its manufacture and supply.8 The APVMA also run a Chemical Review Program and an Adverse Experience Reporting Program.

The control of use of pesticides and veterinary medicines beyond the point of retail sale is the responsibility of state and territory governments (Table 1a).

Food products: the Legislative and Governance Forum on Food Regulation and Food Standards Australia New Zealand

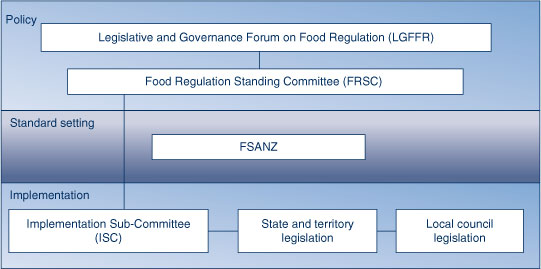

The Legislative and Governance Forum on Food Regulation (LGFFR) is responsible for the development of domestic regulatory policies for food and the development of domestic policy guidelines for setting food standards (Figure 4).

Under the LGFFR is the Food Regulation Standing Committee (FRSC) which is responsible for coordinating policy advice to the LGFFR.

Sitting below the FRSC is the Implementation Sub- Committee (ISC) which develops and supervises the implementation and enforcement of food regulations and standards across the jurisdictions.

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) is the national food regulator responsible for developing and maintaining the Food Standards Code and ensuring the protection of public health and safety around food issues. The Food Standards Code regulates the use of ingredients, the composition of some foods, and the presence of contaminants from food contact materials and environmental sources. FSANZ is also responsible for the labelling of both packaged and unpackaged food. It sets maximum levels for chemicals in food, which includes incorporating pesticide Maximum Residual Levels set by APVMA into food law.

In developing or reviewing any food regulatory measures, FSANZ must have regard to any policy guidelines set by the LGFFR. The implementation and enforcement of the Foods Standards Code is the responsibility of the ISC, and state and local governments.

Defective products: Legislative and Governance Forum on Consumer Affairs and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission

Policy direction around consumer protection stems from the Legislative and Governance Forum on Consumer Affairs (CAF), the ministerial council of federal and state ministers for consumer affairs (Figure 5). Under the CAF sits Consumer Affairs Australia New Zealand (CAANZ), consisting of heads of state and federal consumer affairs departments. In turn, the CAANZ receives policy advice from three advisory committees and the Product Safety Consultative Committee (PSCC). The PSCC provides advice and recommendations on product safety specific policy, education and compliance matters. It also provides advice to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) on proposed product safety regulations, bans, standards and responses to emerging issues.9

The ACCC is the national regulator of consumer products and administers the Commonwealth Competition and Consumer Act 2010. This Act sets out the Australian Consumer Law.

The powers that the ACCC has over product safety are of most relevance here. Under the Act the Assistant Treasurer has powers to recall or ban products that do not meet certain standards, are defective, or create an imminent risk of death, serious illness or serious injury. The ACCC can undertake assessments of the chemical hazards in products, which may be in conjunction with the National Industrial Chemicals Notification and Assessment Scheme (NICNAS).

The Australian Consumer Law is designed to create a consistent approach to the banning or recalling of products in Australia. As such, state and territory governments are limited in their approaches to recall or ban a product, which will occur at the national level. State and territories have the ability to impose interim bans and consult with the national regulator about product safety issues.

Industrial chemicals: National Industrial Chemicals Notification and Assessment Scheme

Industrial chemicals has developed as a residual category. If a chemical does not fit into any other Australian regulatory scheme, it will fall under the Industrial Chemicals portfolio. As such, the Department of Health and Ageing, of which NICNAS is a part, has representation on the SCOC.

NICNAS is the Australian regulator of industrial chemicals. It undertakes assessment of all new industrial chemicals on the Australian market and is also considering the assessment of over 38 000 existing chemicals on the Australian Inventory of Chemical Substances, which may not have undergone assessment under modern guidelines, through the Inventory Multi-tiered Assessment and Prioritisation Program.10 NICNAS also provides advice to other agencies regarding individual chemical contamination of products, and maintains strong links with the ACCC in this regard.

Although NICNAS has no authority to ban or phase out a chemical, it does have the power to prescribe conditions of use of a chemical which can be adopted and implemented through relevant state and territory legislation; it may also make recommendations to the PS for referral to the ACCS for inclusion of the chemical on the SUSMP.

Environmental health chemicals policy and chemical exposure standards: the Standing Council on Environment and Water and the National Environment Protection Council

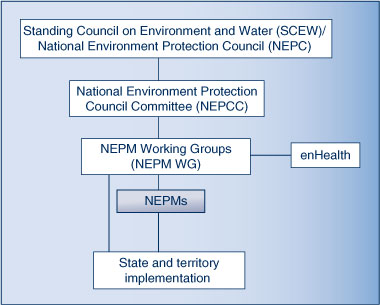

The Standing Council on Environment and Water (SCEW) addresses broad national policy issues relating to environmental management and protection. Incorporated within the SCEW is the National Environment Protection Council (NEPC), a statutory ministerial council that has the power to create National Environment Protection Measures (NEPMs). NEPMs are broad framework-setting statutory instruments that may consist of goals, standards, protocols and guidelines. They provide guidance on issues such as air and water quality, land contamination and hazardous waste. State and federal health agencies also have an active role in the development of NEPMs through enHealth which has membership on the various NEPM Working Groups (NEPM WG).11 State and territory governments have agreed to implement the NEPMs within their jurisdictions.

Importation regulation: Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service and Australian Customs and Border Protection Service

The Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service (AQIS) administer the Imported Food Inspection Scheme. Under this scheme, food is inspected according to the level of risk it may pose to the population as determined by FSANZ. Testing may include targeted hazardous contaminants, pesticides and antibiotics, microbiological contaminants, natural toxicants, metal contaminants and food additives.12 In addition to the routine testing of imported food, AQIS conducts survey testing of imported food. It receives this direction from the ISC.

The powers of the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (ACBPS) stem from the Commonwealth Customs Act 1901, the Commonwealth Customs Tariff Act 1995 and related legislation. However, ACBPS also administers legislation on behalf of other government agencies. In terms of products inappropriately contaminated with chemicals the ACBPS has the power to hold, seize, test and in certain circumstances recall products. This will often be undertaken in consultation with NICNAS, OCS, TGA, AQIS, APVMA, ACCC and the Australian Federal Police depending on the type of chemical or product (personal communication, D Hunt, 15 September 2010).

Additional Standing Councils relevant to chemicals regulation and policy

There are a number of other Standing Councils, regulators and policy bodies that deal with a range of issues relating to chemicals including water, transport, land use planning and acute exposure to chemicals and the emergency management of chemical-related incidents pertaining to them (Tables 1a and 1b) (Figure 1).

Conclusion

This paper describes the system of chemical regulators and government policy bodies responsible for protecting public health in Australia. Understanding this system should be paramount to any policy maker or public health worker in the area of chemical exposure as it is essential for effective environmental health responses and policy development, and will lead to greater efficacy in environmental health outcomes.

|

|

|

|

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr Sarah Potter for her input.

References

[1] National Industrial Chemicals Notification and Assessment Scheme. Existing Chemicals. Available at: http://www.nicnas.gov.au/Industry/Existing_Chemicals.asp (Cited 22 November 2012).[2] Capon A, Sheppeard V. Consumer product safety and chemical contamination. Public Health Bulletin SA 2010; 7 43–8.

[3] Rae A. Federalism in the Regulation of Chemical Pollutants in Australia. Prometheus 2003; 21 247–64.

| Federalism in the Regulation of Chemical Pollutants in Australia.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar |

[4] Regulation Taskforce. Rethinking Regulation: Report of the Taskforce on Reducing Regulatory Burdens on Business, Report to the Prime Minister and the Treasurer, Canberra. 2006. Available at: http://www.regulationtaskforce.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/69721/regulation-taskforce.pdf (Cited 10 September 2012).

[5] Department of Innovation Industry Science and Research. Standing Committee on Chemicals. 2010. Available at: http://www.innovation.gov.au/INDUSTRY/CHEMICALSANDPLASTICS/SCOC/Pages/default.aspx (Cited 10 September 2012).

[6] National Coordinating Committee on Therapeutic Goods. Scheduling Policy Framework for Medicines and Chemicals. Available at: http://www.tga.gov.au/scheduling-policy-framework.doc (Cited 10 September 2012).

[7] Therapeutic Goods Administration. Advisory committees on medicines and chemicals scheduling. Available at: http://www.tga.gov.au/about/committees-acmcs.htm (Cited 12 September 2012).

[8] Productivity Commission. Chemicals and Plastics Regulation. Melbourne: Commonwealth of Australia; 2008.

[9] Commonwealth of Australia. SCOCA Standing Advisory Committees and Consultative Committees – Structure and Operation. Commonwealth of Australia; 2009.

[10] National Industrial Chemicals Notification and Assessment Scheme. Inventory Multi-tiered Assessment and Prioritisation. Available at: http://nicnas.gov.au/industry/existing_chemicals/chemicals_On_AICS.asp (Cited 25 October 2012).

[11] Department of Health and Ageing. Environmental Health Committee (enHealth). Available at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/ohp-environ-enhealth-committee.htm (Cited 10 September 2012).

[12] Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service. Imported Food Inspection Scheme. Available at: http://www.daff.gov.au/aqis/import/food/inspection-scheme (Cited 10 September 2012).