NSW Annual Vaccine-Preventable Disease Report, 2010

Paula J. Spokes A B and Robin E. Gilmour AA Communicable Diseases Branch, NSW Department of Health

B Corresponding author. Email: pspok@doh.health.nsw.gov.au

NSW Public Health Bulletin 22(10) 171-178 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB11028

Published: 8 November 2011

Abstract

Aims: To describe trends in case notification data for vaccine-preventable diseases in NSW for 2010. Methods: Risk factor and vaccination status data were collected from cases through public health unit follow-up. Data from the NSW Notifiable Conditions Information Management System (NCIMS) were analysed by: local health district of residence; age; vaccination status; and sub-organism, where available. Results: Outbreaks of measles and pertussis were notified in 2010, associated with unimmunised groups (measles) or as a result of waning immunity (pertussis). Conclusion: With the exception of pertussis, most vaccine-preventable disease notifications remain low in NSW. Ensuring high levels of vaccination for travellers is important to prevent future outbreaks of vaccine-preventable disease, particularly measles.

The objectives of vaccine-preventable disease surveillance are to: detect and investigate outbreaks of vaccine-preventable disease; identify contacts of patients who may be at risk of infection; identify cases of potential vaccine failure; and understand the epidemiology of vaccine-preventable disease to inform the development of prevention strategies. Notified cases of vaccine-preventable disease were defined according to national criteria.1 Under the NSW Public Health Act 1991, since 1991: medical practitioners have been required to notify patients diagnosed with measles and pertussis; laboratories have been required to notify patients diagnosed with measles, pertussis, rubella, Haemophilus influenzae serotype b invasive infection, meningococcal disease, mumps and rubella; and hospital general managers have been required to notify patients diagnosed with measles, pertussis, H. influenzae serotype b invasive infection, and meningococcal disease, to NSW Health (via public health units). Laboratories have also been required to notify patients with invasive pneumococcal infections since 2002.

Notifications of H. influenzae serotype b invasive infection, measles, meningococcal disease, pertussis, pneumococcal disease (people aged less than 5 years and 50 years and over) and tetanus prompt public health follow-up according to NSW case definitions and response protocols.2 Notifications of mumps and rubella are not routinely followed-up by public health units in NSW.2 Public health unit staff enter data gathered on notified cases into the statewide Notifiable Conditions Information Management System (NCIMS). This report describes notifications of vaccine-preventable diseases in New South Wales (NSW) in 2010 and compares this with recent trends in surveillance data.

Methods

Notification data from the NSW NCIMS were reviewed for cases of vaccine-preventable diseases with a date of onset in 2010. All rates were calculated using Australian Bureau of Statistics population estimates for the relevant year. Rates are presented as annual rates per 100 000 total population or population in age groups. Risk factor and vaccination status data were collected from notified cases through public health unit follow-up. In NSW, laboratories provide serotype data for measles, meningococcal and pneumococcal disease. Notified cases were analysed by place of usual residence according to geographical regions served by the relevant local health districts’ public health unit.

Results

Haemophilus influenzae serotype b invasive infection

H. influenzae serotype b (Hib) is a bacillus which may form part of the flora of the upper respiratory tract. The bacteria are spread through contact with droplets from the nose or throat of a person with the infection, usually in household-like settings. Infection can result in invasive disease including meningitis, epiglottitis, septic arthritis, cellulitis and pneumonia.3 Since 1993, vaccination against H. influenzae serotype b has been available and is provided for infants at 2, 4, 6 and 12 months of age.4 In 2006, the H. influenzae serotype b vaccine changed to PRP-T from PRP-OMP.

Summary of notified cases

In 2010, six cases of H. influenzae serotype b infection were notified which is similar to previous years. Two cases were children aged less than 1 year, two cases were children aged between 1–6 years, and two cases were adults aged 35 and 55 years. Three cases were male; no cases were notified in Aboriginal people in 2010.

Vaccination status of cases

Of the four cases of H. influenzae serotype b infection notified in children in 2010, one was unvaccinated and three were fully vaccinated for their age (an infant aged 7 months with three doses and two children aged 3 years with four doses).

Comment

H. influenzae serotype b is now rarely seen in NSW children. H. influenzae serotype b vaccination has successfully reduced the rate of disease incidence in unvaccinated populations.

Measles

Measles is an acute, highly infectious viral disease that can have serious complications. Prodromal symptoms of measles include fever, tiredness, cough, runny nose, sore red eyes and feeling unwell. A characteristic rash appears 3–7 days after the prodrome, beginning on the face and spreading down the body. The rash usually lasts 4–7 days.3

Summary of notified cases

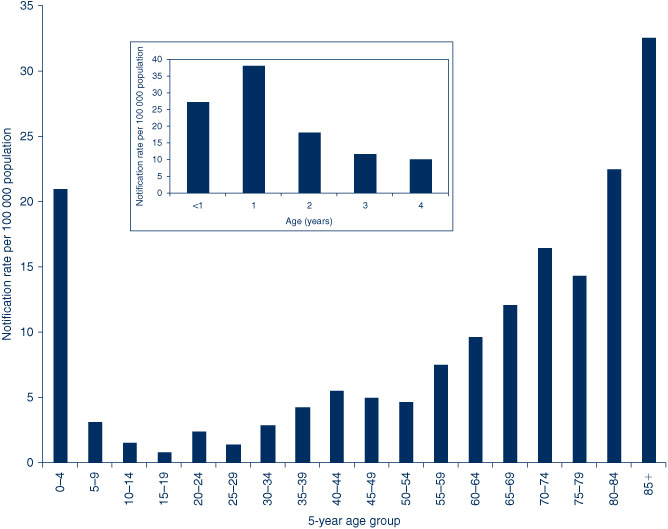

In 2010, 26 cases of measles were notified in NSW, compared to 19 in 2009. The highest notification rates were reported among young people aged at onset of their illness 10–14 years (10 cases, 2.2 per 100 000 population) and 15–19 years (seven cases, 1.5 per 100 000 population) (Figure 1). Eighteen cases (69%) were male; no cases were notified in Aboriginal people. Geographically, the highest notification rates were reported from the Northern NSW Local Health District (4.0 per 100 000 population) (Table 1).

|

|

Vaccination status of cases

Of the 26 cases, 18 (69%) were unvaccinated, two (8%) were vaccinated, two (8%) were partially vaccinated and four adult cases (15%) were unable to recall their vaccination status.

Outbreaks

Most cases of measles in NSW are notified either in non-immune travellers who return with the infection from countries where measles is endemic, or in non-immune people who are exposed to a known case.5 Of the 26 cases notified in 2010, six (23%) were associated with overseas travel. Three of these cases resulted in further transmission affecting 20 people. One case who acquired the infection overseas was associated with transmission to one unvaccinated family member and one unvaccinated community contact. A second case who acquired the infection overseas was associated with transmission to three unvaccinated family members and one airplane contact with uncertain vaccination history. A third overseas case, from the Northern NSW Local Health District, was associated with transmission in a high school (eight cases), a prison (four cases) and the community (two cases).

Genotype

There are different genotypes of the measles virus. In 2010, eight cases had measles genotype information identified. Of these, one were identified as H1 (associated with travel to Vietnam), one was D8 (associated with travel to Sri Lanka), one was D4 (associated with travel to Italy), and five were D9 (one associated with travel to China, and four from the Northern NSW Local Health District cluster initially associated with travel to Malaysia).

Comment

People at risk of contracting measles are those who have never had measles or who have never been vaccinated. A second dose of measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine was added to the National Immunisation Program in 1992.4 Endemic genotypes of the measles virus have disappeared through control. The variety of genotypes described indicates that most cases are imported.

Invasive meningococcal disease

Invasive meningococcal disease is an acute bacterial disease that typically causes septic shock or meningitis (or a combination of both).3 Invasive meningococcal disease is caused by infection with meningococcus bacteria, of which there are several serogroups. A vaccine against serogroup C meningococcal disease was added to the National Immunisation Program in 2003 for children at 12 months of age and offered to all people aged 1–19 years between 2003 and 2004.4

Summary of notified cases

In 2010, 74 cases of invasive meningococcal disease were notified in NSW (66 confirmed and eight probable), compared with 92 cases notified in 2009. Five deaths were notified in 2010 (three caused by serogroup B, one serogroup W135, and one with an unknown serogroup) compared to four deaths in 2009 (two caused by serogroup B, one serogroup W135, and one with an unknown serogroup).

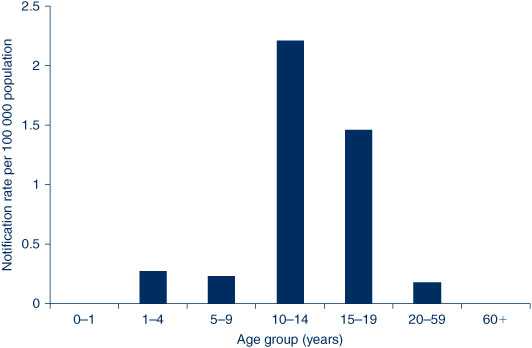

The highest notification rates of invasive meningococcal disease were among children aged less than 5 years at onset of illness (29 cases, 6.2 per 100 000 population) and young people aged 15–19 years (10 cases, 2.1 per 100 000 population). Of the notifications among children aged less than 5 years, the highest rates were reported from children aged 12–24 months (10 cases, 10.1 per 100 000 population) and infants aged less than 12 months (eight cases, 8.4 per 100 000 population) (Figure 2).

In 2010, 36 cases (49%) of invasive meningococcal disease were in males. Seven cases were notified in Aboriginal people. Geographically, the highest notification rates were from the Central Coast (3.2 per 100 000 population) and Illawarra Shoalhaven Local Health Districts (2.1 per 100 000 population) (Table 1).

Vaccination status of cases

Information describing vaccination status was complete for 60 cases (81%). Of the cases with known vaccination status, 37 (62%) were vaccinated against serogroup C. Of the vaccinated cases, 29 (78%) were from serogroup B (for which there is no vaccine), one (3%) was from serogroup W135 and six (16%) were unable to be typed. No cases reported in people who were vaccinated were due to serogroup C.

Serogroup

Of the 74 cases notified in NSW in 2010, serogroup information was recorded for 62 (84%). Of the cases with known serogroup information, 49 (79%) were caused by serogroup B (for which there is no vaccine), six (10%) were serogroup C, four (6%) were serogroup W135 and three (5%) were serogroup Y. Of the 12 cases (19%) with unknown serogroup information, the serogroup could not be typed for five cases and seven cases were clinical diagnoses.

Comment

The number of notified cases of invasive meningococcal disease has declined significantly since the National Meningococcal C Immunisation Program commenced in 2003. The greatest reduction in notified cases of meningococcal disease has been for serogroup C, from 44 cases (29%) with known serogroup in 2003 to six cases (10%) in 2010. Serogroup C meningococcal disease is now mainly reported from young adults (aged 15–29 years) and unimmunised children. The number of cases of meningococcal disease associated with serogroup B has also decreased over time. However, due to reductions in serogroup C disease, notifications of serogroup B disease now account for a larger proportion of the meningococcal disease notifications in NSW. Serogroups not included in vaccines (W135 and Y) have remained relatively stable over time.

Mumps

Mumps is an acute infectious disease caused by the mumps virus. Common symptoms of mumps include fever, loss of appetite, tiredness and headaches followed by swelling and tenderness of the salivary glands. Illness is usually more severe in people who contract the infection after puberty.3 In NSW, vaccination is provided using MMR vaccine at 12 months and 4 years of age.4

Summary of notified cases

In 2010, 38 cases of mumps were notified in NSW compared to 40 in 2009. The highest notification rates of mumps were among young adults aged 25–29 years at onset of illness (10 cases, 2.0 per 100 000 population). In 2010, 13 cases (34%) were male. Geographically, the highest rates were notified from the Sydney Local Health District (1.1 per 100 000 population) (Table 1).

Comment

In NSW, notified cases of mumps are not routinely followed up by public health units. A significant increase in mumps notifications (largely from young adults in the South Eastern Sydney Local Health District) was reported in 2007.6 No outbreaks or clusters of mumps cases were notified in 2010.

Pertussis

Pertussis (or whooping cough) is a disease caused by infection of the throat with the bacteria Bordetella pertussis. Pertussis can be very serious in small children. Older children and adults may have a less serious illness, with bouts of coughing that continue for many weeks regardless of treatment.3 Pertussis vaccination is combined with diphtheria and tetanus (DTPa) in a primary course at 2, 4 and 6 months of age (can be given at 6 weeks of age) and a booster at 4 years of age (can be given from 3½ years). A second booster dose is given between 15 and 17 years of age using the adult dTpa formulation.4

Summary of notified cases

In 2010, 9287 cases of pertussis were notified in NSW compared with 12 448 in 2009. Following an epidemic period during 2008 and 2009,7 notifications of pertussis declined and stabilised in the first half of 2010 (2376 notified to 30 June 2010) compared to the same period in 2009 when 8777 cases were notified. Notifications of pertussis increased during the second half of 2010 (6911), peaking in November at 1866 cases.

The highest pertussis notification rates were in children aged 5–9 years (2730 cases, 616.9 per 100 000 population) and 10–14 years (1614 cases, 356.5 per 100 000 population). The age groups 5–9 and 10–14 years were the only age groups showing an increase in notification rates in 2010 compared with 2009, in contrast to younger age groups. Notifications of pertussis in children aged 0–4 years were significantly lower in 2010 (1394 cases, 298.8 per 100 000 population) compared to 2009 (2821 cases, 621.6 per 100 000 population). Of the cases aged less than 5 years, the highest notification rates were in children aged 3 years (364 cases, 384.7 per 100 000 population) and infants aged less than 12 months (302 cases, 315.4 per 100 000 population) (Figure 3).

In 2010, 4026 cases (43%) were male. Of the 1394 cases aged 0–4 years (who are followed up by public health units), 49 (4%) were notified in Aboriginal children. Geographically, the highest notification rates were reported in the Far West (260.3 per 100 000 population), Murrumbidgee (196.8 per 100 000 population) and North Sydney (195.5 per 100 000 population) Local Health Districts (Table 1).

Vaccination status of cases

In 2010, 302 cases were notified in infants aged less than 12 months of age. Of these, 204 (68%) were infants too young to be fully vaccinated. Of the 1092 cases of pertussis notified in children aged 1–4 years, 83 (8%) had no immunisation recorded, 123 (10%) had less than three doses of vaccine recorded, and 882 (81%) had three or more doses recorded.

Comment

In 2010, the number of notifications of pertussis was significantly lower in children aged 0–4 years compared to the previous year. This was particularly striking for children aged 3 years at onset of illness (384.7 per 100 000 population in 2010 compared to 810.9 per 100 000 population in 2009) and infants aged less than 12 months of age (315.4 per 100 000 population in 2010 compared to 677.2 per 100 000 population in 2009).

The reduction in notifications in these age groups may be in part due to a statewide community awareness campaign to protect infants. The key messages were: for infants to receive their first dose of vaccine at 6 weeks (from 8 weeks); for children to receive their first booster dose of vaccine at 3½ years (from 4 years); and to promote free vaccination for new parents, grandparents and carers of infants.8

Pneumococcal disease (invasive)

Pneumococcal disease is caused by infection with the bacteria Streptococcus pneumonia and is a frequent cause of serious bacterial infections.3 There are more than 90 different serotypes that can cause the disease. Vaccines for children aged less than 5 years (7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine – 7vPCV) and adults older than 65 years (23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine – 23vPPV) were introduced into the National Immunisation Program in 2005.4 In NSW, cases of all ages are notified, but only those aged less than 5 years or older than 50 years are routinely followed up by public health units to gather vaccination and serotype data.

Summary of notified cases

In 2010, 503 cases of invasive pneumococcal disease were notified compared to 478 in 2009. Forty-six deaths were identified in 2010 compared to 53 in 2009. Two deaths were notified in fully vaccinated children aged less than 2 years (disease caused by serotypes not included in the vaccine), five in people aged 5–49, and 39 in people aged older than 50 years.

The highest notification rates of invasive pneumococcal disease were in adults aged older than 85 years (45 cases, 32.6 per 100 000 population), 80–84 years (34 cases, 22.5 per 100 000 population) and children aged less than 5 years (98 cases, 21.1 per 100 000 population) (Figure 4). Of the cases aged less than 5 years, the highest notification rates were in children aged 12–23 months (35 cases, 38.0 per 100 000 population) and infants aged less than 12 months (26 cases, 27.2 per 100 000 population).

Fifty-six percent of cases were male. Of the 371 cases aged 0–4 years or older than 50 years (who are followed up by public health units), 13 (4%) were notified in Aboriginal people. Geographically, the highest notification rates were reported in the Western NSW (10.0 per 100 000 population), South Eastern Sydney (8.7 per 100 000 population) and Nepean Blue Mountains (8.3 per 100 000 population) Local Health Districts (Table 1).

Serotype

Of the 503 cases of invasive pneumococcal disease notified in 2010, 400 (80%) had complete serotype information. For children aged less than 5 years with known serotype information, 92 (94%) were notified with serotypes not included in the 7vPCV, two (2%) were notified with invasive disease caused by a serotype included in the 7vPCV (19F and 23F), and four (4%) were unable to be typed. For people aged 5–49 years with known serotype information, 95 (81%) were notified with serotypes not included in the 7vPCV, 17 (15%) were notified with invasive disease caused by a serotype included in the 7vPCV, and five (4%) were unable to be typed. For adults aged older than 50 years, 70 cases (28%) were caused by a non-vaccine-related serotype.

Comment

Invasive pneumococcal disease has significantly decreased in children aged less than 5 years, with moderate reductions in adults aged older than 50 years, following the addition of pneumococcal vaccine onto the National Immunisation Program in 2005.9 In children, disease caused by serotypes included in the 7vPCV are uncommon, however, disease caused by serotypes not included in the 7vPCV has continued to increase (particularly disease caused by serotype 19A).

Rubella

Rubella (or German measles) is an infectious viral disease. Although a mild infection in most people, infection in early pregnancy can cause serious birth defects or miscarriage. Rubella is spread from a person with the infection by droplets from the nose or mouth or by direct contact.3 Rubella is easily spread to people who have not been vaccinated or not previously had the infection. Rubella vaccination is provided using MMR vaccine at 12 months and 4 years of age.4

Summary of notified cases

In 2010, 13 cases of rubella were notified in NSW compared to seven in 2009. All cases were notified in adults aged 20–50 years. Six cases (46%) were male. Geographically, the highest notification rates were in the Central Coast Local Health District (0.6 per 100 000 population) (Table 1).

Comment

It is likely that many cases of rubella are diagnosed clinically and are never confirmed by pathology tests. Therefore, the notifications are likely to represent an underestimation of the true incidence of rubella in the community. Rubella cases are not routinely followed up by public health units in NSW. Notifications have declined over time.

Tetanus

Tetanus is a disease caused by the bacteria Clostridium tetani. Toxin made by the bacteria, which grows at the site of an injury, attacks a person's nervous system. Although now rare due to immunisation, tetanus can be fatal. C. tetani bacteria are found in dust and animal faeces and infection may occur after minor injury (sometimes unnoticed punctures to the skin that are contaminated with soil, dust or manure) or after major injuries such as open fractures, dirty or deep penetrating wounds, and burns.3 Tetanus is not passed from one person to another. Vaccination against tetanus is given to children with diphtheria and pertussis (DTPa) in a primary course at 2, 4 and 6 months of age. A booster dose of DTPa is given at 4 years.4 A second booster dose has been included in the National Immunisation Program for those aged 15–17 years since 2004 using the adult dTpa formulation.

Summary of notified cases

In 2010, one case of tetanus was notified in NSW. The case, an elderly man, was unsure of his vaccination history.

Comment

The number of notified cases of tetanus has remained relatively stable over the past 5 years, ranging from one to two cases annually. In Australia, tetanus mostly occurs in older adults who are not adequately immunised.

Discussion

The numbers of notified cases of many vaccine-preventable diseases remain low in NSW, however, outbreaks do occur. High rates of pertussis infection have been notified in recent years, in part due to waning immunity and increased use of more sensitive tests. Outbreaks of measles have occurred as a result of non-vaccinated people travelling to countries where vaccine-preventable disease is more common. Maintaining high levels of vaccination coverage for overseas travellers is important for future vaccine-preventable disease control, particularly for measles.

Notification data for vaccine-preventable diseases are subject to several limitations and are likely to underestimate the true incidence of disease. Firstly, some infections can be mild, so people may not present for medical attention. Secondly, for those who do present to healthcare providers, notification relies on a diagnosis being made and in the absence of a doctor notifying the case, appropriate laboratory tests being ordered. Thirdly, positive diagnoses may not be notified by the doctor, laboratory or hospital to public health units as required under the Public Health Act for a variety of reasons. Nonetheless, assuming these biases are relatively stable over time, vaccine-preventable disease notification data do provide a useful indication of the trends in disease incidence in NSW.

Conclusion

With the exception of pertussis, most vaccine-preventable diseases are currently notified in low numbers in NSW. This is the result of reaching and maintaining high vaccination coverage levels. Notification and disease estimates from surveillance systems can be affected by changes in disease awareness, laboratory diagnostic tests and testing protocols, case definitions, and reporting practices over time. However, ongoing surveillance for vaccine-preventable disease is important to identify changes to disease incidence and to inform appropriate public health action.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank and acknowledge the NSW public health network including laboratory staff for their work in identifying and managing cases of vaccine-preventable disease in NSW.

References

[1] Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Australian national notifiable diseases case definitions. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/cdna-casedefinitions.htm (Cited June 2011.)[2] Communicable Diseases Branch. NSW Department of Health. Disease Control Guidelines. Available from: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/publichealth/Infectious/controlguide.asp (Cited June 2011.)

[3] Heymann DL, ed. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual. 19th ed. Washington: American Public Health Association; 2008.

[4] National Health and Medical Research Council. The Australian Immunisation Handbook. 9th ed. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2008.

[5] Brotherton J. EpiReview: Measles in NSW, 1991–2000. N S W Public Health Bull 2001; 12 200–4.

| EpiReview: Measles in NSW, 1991–2000.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar |

[6] Ferson MJ, Konecny P. Recent increases in mumps incidence in Australia: the ‘forgotten’ age group in the 1998 Australian Measles Control Campaign. Med J Aust 2009; 190 283–4.

[7] Spokes PJ, Quinn HE, McAnulty JM. Review of the 2008–2009 pertussis epidemic in NSW: notifications and hospitalisations. N S W Public Health Bull 2010; 21 167–73.

| Review of the 2008–2009 pertussis epidemic in NSW: notifications and hospitalisations.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar |

[8] Whooping Cough information campaign, NSW Department of Health. Available from: http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/PublicHealth/Infectious/whoopingcough/index.asp (Cited June 2011).

[9] Gilmour R. EpiReview: Invasive pneumococcal disease, NSW, 2002. N S W Public Health Bull 2005; 16 26–30.