NSW Annual Report Describing Adverse Events Following Immunisation, 2011

Deepika Mahajan A D , Su Reid B , Jane Cook C , Kristine Macartney A and Robert I. Menzies AA National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance, The Children’s Hospital at Westmead

B Health Protection NSW

C Office of Medicine Safety Monitoring, Therapeutic Goods Administration

D Corresponding author. Email: DeepikM2@chw.edu.au

NSW Public Health Bulletin 23(10) 187-200 https://doi.org/10.1071/NB12081

Published: 12 December 2012

Abstract

Abstract: Aim: This report summarises Australian passive surveillance data for adverse events following immunisation in NSW for 2011. Methods: Analysis of de-identified information on all adverse events following immunisation reported to the Therapeutic Goods Administration. Results: 449 adverse events following immunisation were reported for vaccines administered in 2011; this is slightly higher than in 2010 (n = 439) and the second highest number since 2003. The most commonly reported reactions were injection site reaction, fever, allergic reaction and malaise. A large number of injection site reactions were reported following administration of the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in adults aged 65 years and over (97.4/100 000 doses) and in children aged less than 7 years following administration of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (29.4/100 000 doses) and combined diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (acellular) and inactivated poliovirus (quadrivalent)-containing vaccines (47.1/100 000 doses). Only 10% of the reported adverse events were categorised as serious. There were two reports of death however both were attributed to causes other than vaccination. Conclusion: The increased number of reports in 2011 is attributable to the high rates of injection site reactions in children associated with the administration of combined diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis (acellular) and inactivated poliovirus (quadrivalent)-containing vaccines and the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, as well as in adults following receipt of the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine.

An adverse event following immunisation is defined as any untoward medical occurrence which follows immunisation and which does not necessarily have a causal relationship with the usage of the vaccine.1 The adverse event may be any unfavourable or unintended sign, abnormal laboratory finding, symptom or disease.1

Thus, adverse events may be caused by a vaccine(s) or may be coincidental. Adverse events may also include conditions that occur following the incorrect handling and/or administration of a vaccine(s). Post-licensure surveillance – the practice of monitoring the safety of a vaccine after it has been licensed and released in the market – is particularly important to detect rare, late onset and unexpected events which are difficult to detect in pre-licensure vaccine trials.

This is the third annual report for adverse events following immunisation in New South Wales (NSW). It summarises passive surveillance data reported from NSW in 2011 and describes reporting trends over the 12-year period 2000–2011. To assist readers, a glossary of the abbreviations of the vaccines referred to in this report is provided in Box 1.

|

Trends in reported adverse events following immunisation are influenced by changes to vaccines provided through the National Immunisation Program. Changes in previous years have been reported elsewhere.2–10 Two recent changes influenced the adverse events surveillance data presented in this report:

-

From 1 July 2011, Prevenar 13® (13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, 13vPCV) replaced Prevenar® (7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, 7vPCV) on the National Immunisation Program for children at 2, 4 and 6 months of age in all states and territories except the Northern Territory (which adopted 13vPCV from 1 October 2011).11 Children aged 12–35 months who had completed a primary pneumococcal vaccination course with 7vPCV are eligible to receive a free supplementary dose of Prevenar 13® from 1 October 2011 to 30 September 2012.

-

On 25 March 2011, the Therapeutic Goods Administration issued a recall of Batch N3336 of Pneumovax® 23 (23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine, 23vPPV) as a precautionary measure following an increased number of reports of adverse reactions in patients who had received the vaccine.12 Further advice to health professionals not to administer a second or subsequent dose of Pneumovax® 23 vaccine was provided in April 2011.13 Revised recommendations regarding which patients should be re-vaccinated under the National Immunisation Program was provided in December 2011.14

Methods

Adverse events following immunisation (AEFI) are notifiable to public health units by medical practitioners and hospital Chief Executive Officers under the NSW Public Health Act 1991.* Case-patients with outstanding information and all serious adverse events are followed up by public health units and the NSW Ministry of Health, and all notifications are forwarded to the Therapeutic Goods Administration. The Therapeutic Goods Administration also receives reports directly from vaccine manufacturers, members of the public and other sources.15,16

AEFI data

All reports are assessed by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) using internationally-consistent criteria17 and entered into the Australian Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting System database. The term ‘AEFI record’ is used throughout this report because a single adverse event notification to the TGA can generate more than one record in the Australian Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting System database. This may occur if there is a time sequence of separate adverse reactions in a single patient.

Typically, each AEFI record lists several symptoms, signs and diagnoses that have been coded by TGA staff from the description provided by the reporter into standardised terms using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA®).18

Study definitions of AEFI outcomes and reactions

AEFI records are classified by medical officers within the TGA as ‘suspected’ to be causally related to immunisation. An AEFI record is classified as ‘not suspected’ and excluded from the Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting System database if: there is no reasonable temporal association between the use of a drug and the clinical event (generally described as onset of symptoms within 28 days following vaccination); the record does not contain enough information for an adequate assessment or the information is contradictory; or if a clinical event is explained as likely to have arisen from other causes.

Because children generally receive several vaccines at the same time, all administered vaccines are usually listed as ‘suspected’ of involvement in a systemic adverse event as it is usually not possible to attribute the event to a single vaccine.

AEFIs were defined as ‘serious’ or ‘non-serious’ based on information recorded in the Australian Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting System database and using criteria similar to those used elsewhere.17,19 In this report, an AEFI is defined as ‘serious’ if the record indicated that the person had recovered with sequelae, been admitted to a hospital, experienced a life-threatening event, or died.

Data analysis

De-identified information on AEFI reports from the Australian Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting System database was released to the National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance for analysis and reporting. AEFI records contained in the Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting System database were eligible for inclusion in the analysis if: a vaccine was recorded as ‘suspected’ of involvement in the reported adverse event; the vaccination occurred between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2011; and the residential address of the individual was recorded as NSW.

All data analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.1.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Average annual population-based reporting rates were calculated using population estimates obtained from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.20

AEFI reporting rates per 100 000 administered doses were estimated where information on dose numbers was available from: the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register for National Immunisation Program vaccines for children aged less than 7 years; NSW Health data on vaccines administered in schools for 12–17-year-olds; and the 2009 NSW Population Health Survey for influenza vaccines and the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (23vPPV) for adults aged 65 years and over.21 For the 23vPPV vaccine, as a single booster is recommended 5 years after the first dose, the number of respondents who declared being vaccinated within 5 years was divided by five to get an estimate of the average number of doses for a single year.

Notes on interpretation

The data reported here are provisional, particularly for the fourth quarter of 2011, because of reporting delays and the late onset of some reported AEFIs. Numbers are updated for previous years. The information collated in the Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting System database is intended primarily to detect signals of adverse events and to inform hypothesis generation. While AEFI reporting rates can be estimated using appropriate denominators, they cannot be interpreted as incidence rates due to under-reporting and biased reporting of suspected events, and the variable quality and completeness of information provided in individual notification reports.2–10

It is important to note that this annual report is based on vaccine and reaction term information collated in the Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting System database and not on comprehensive clinical notes. Individual records in the database list symptoms, signs and diagnoses that were used to define a set of reaction categories based on the case definitions broadly corresponding to those listed in the 9th edition of The Australian Immunisation Handbook.16

Results

There was a total of 449 AEFI records for NSW in the Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting System database with a date of vaccination (or onset of an adverse event if vaccination date was not reported) in 2011. This was slightly higher than in 2010 (n = 439) but the same as the number reported in 2009 (n = 449). Seventy-two percent (n = 325) of the AEFI records during 2011 were reported in the first two quarters of the year and 42% (n = 138) were following the administration of 23vPPV. Of all reports, 33% (n = 149) were for children aged less than 7 years and 66% (n = 297) were for people aged 7 years and over. Seventy-nine percent of AEFIs (n = 354) were reported to the TGA by NSW Health and the remainder were reported directly to the TGA; 19% (n = 87) by doctors/other health care providers, 1% (n = 6) by hospitals and 0.5% (n = 2) by members of the public. The number of AEFI reports by members of the public was much lower in 2011 than in 2010 (21%, n = 88) and 2009 (33%, n = 149).

Reporting trends

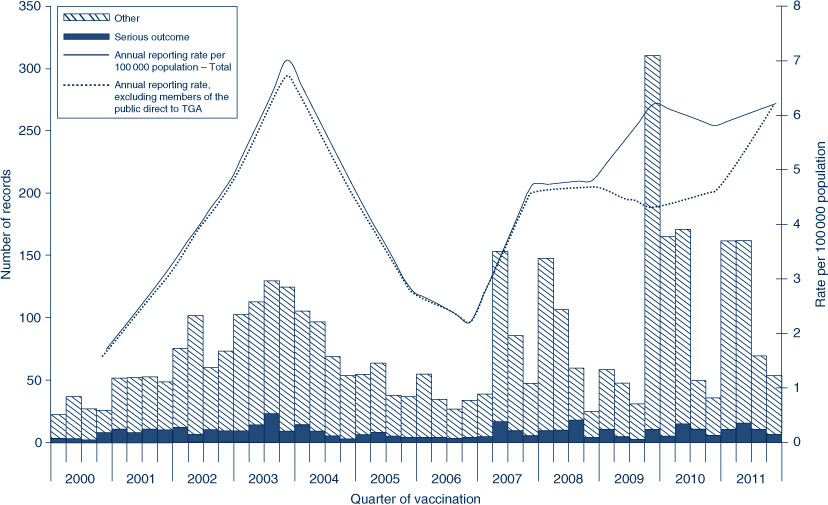

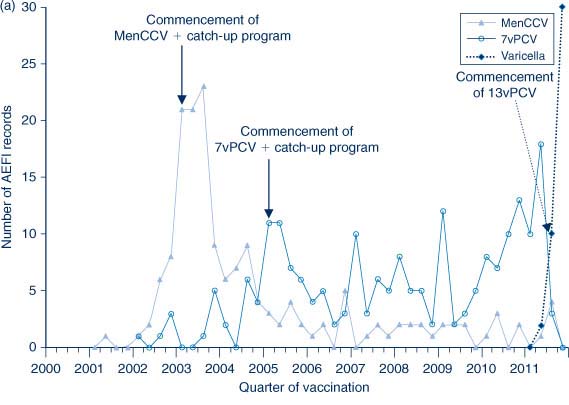

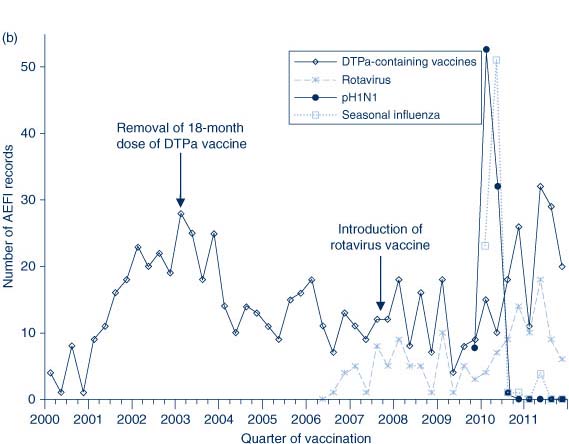

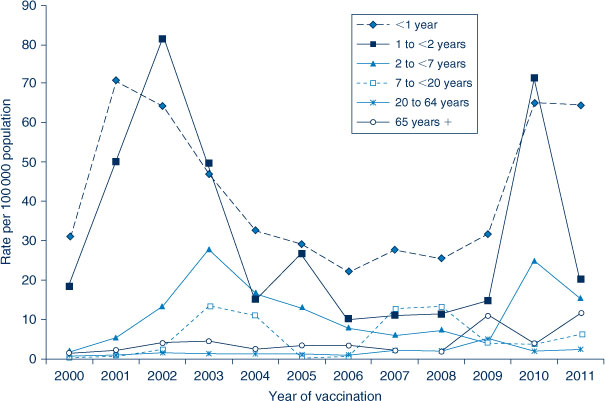

The AEFI reporting rate for 2011 was 6.2 per 100 000 population. This is the third highest reporting rate for the period 2000–2011, after the first peak in 2003 that coincided with the implementation of the national program for meningococcal C conjugate vaccine and catch-up program and high reporting rates from the 18-month dose of DTPa; and the second peak in 2009 following the commencement of the pandemic influenza vaccine (pH1N1) program (Figure 1). Figure 1 shows the increase in reporting by the general public directly to the TGA in 2009 and 2010 which subsided in 2011, and that the majority of reported events (from all reporter types) were of a non-serious nature in all years. Figures 2 and 3 demonstrate marked variations in reporting levels in association with previous changes to the National Immunisation Program from 2000 onwards. Figures 2a and 2b show that the rise in the reporting rate in 2011 was predominantly due to reports following receipt of 7vPCV, 13vPCV (Figure 2a), and DTPa-containing vaccines (Figure 2b) in children aged less than 7 years. There was a spike in AEFI reports following adminisration of 23vPPV in adults (Figure 3).

|

|

|

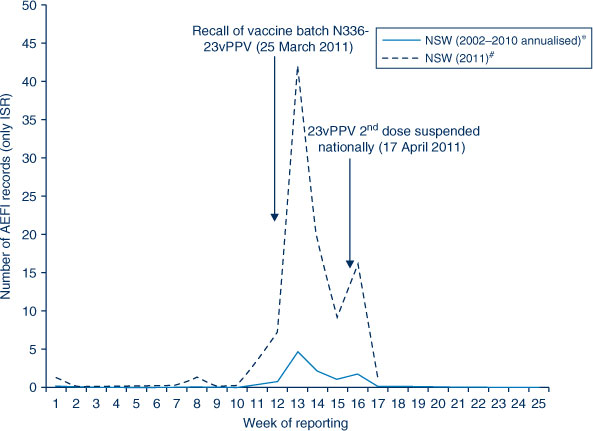

The usual seasonal pattern of AEFI reporting from older Australians receiving 23vPPV and influenza vaccines during the autumn months (March–June) is evident in Figure 3.

Age-specific rates

There was a decrease in the reporting rate in children aged less than 7 years in 2011 compared with 2010 (from 37.9 to 23.4 per 100 000 population). However, the reporting rates were still about 2.5 times higher than in 2009 (9.9 per 100 000 population). In 2011, the highest population-based AEFI reporting rate occurred in infants aged less than 1 year, the age group that received the highest number of vaccines (Figure 4). An increase was observed amongst those aged 7 years and over in 2011 compared to 2010 (4.5 vs 2.7 per 100 000 population respectively) and especially in adults aged 65 years and over (11.9 vs 4.2 per 100 000 population respectively).

|

There were increases in the reporting rates of most individual vaccines in children aged less than 7 years compared to 2010 (except Hib, varicella and MenCCV (Table 1)).17 A significant increase was observed in adolescents (aged 12–17 years) in 2011 compared to 2010 (19.4 vs 6.7 per 100 000 doses), which was more pronounced for HPV (37.9 vs 14.1) and dTpa (24.3 vs 4.3). Reporting rates per 100 000 doses were also significantly higher for adults aged 65 years and over (14.6 vs 5.2), especially for 23vPPV (97.4 vs 23.4) (Table 1).

|

Vaccines

Of the 449 records, the most frequently reported individual vaccine was 23vPPV with 145 records (32%), predominantly in adults aged 65 years and over (n = 108) followed by 18–64 year-olds (n = 32). Five reports were received from those aged less than 18 years (three reports in children aged less than 7 years and two in the 12–17-year age group) (Table 1). Vaccines containing diphtheria, tetanus and acellular pertussis antigens were reported in 165 (37%) records, with dTpa (62 records, 14%), hexavalent DTPa-IPV-HepB-Hib (56 records, 12%) and DTPa-IPV (45 records, 10%) being the most frequently reported among DTPa-containing vaccines. The other frequently reported vaccines were: seasonal influenza vaccine (93 records, 21%), rotavirus (43 records, 10%), HPV and 13vPCV (42 records each, 9%), 7vPCV (32 records, 7%), MMR (29 records, 6%) and varicella (22 records, 5%) (Table 1). Of vaccines where data on doses administered could be estimated, those with the highest AEFI rates per 100 000 doses were 23vPPV for adults aged 65 years and over (97.4), DTP-IPV (47.1), HPV (37.9) and 13vPCV (29.4) (Table 1).

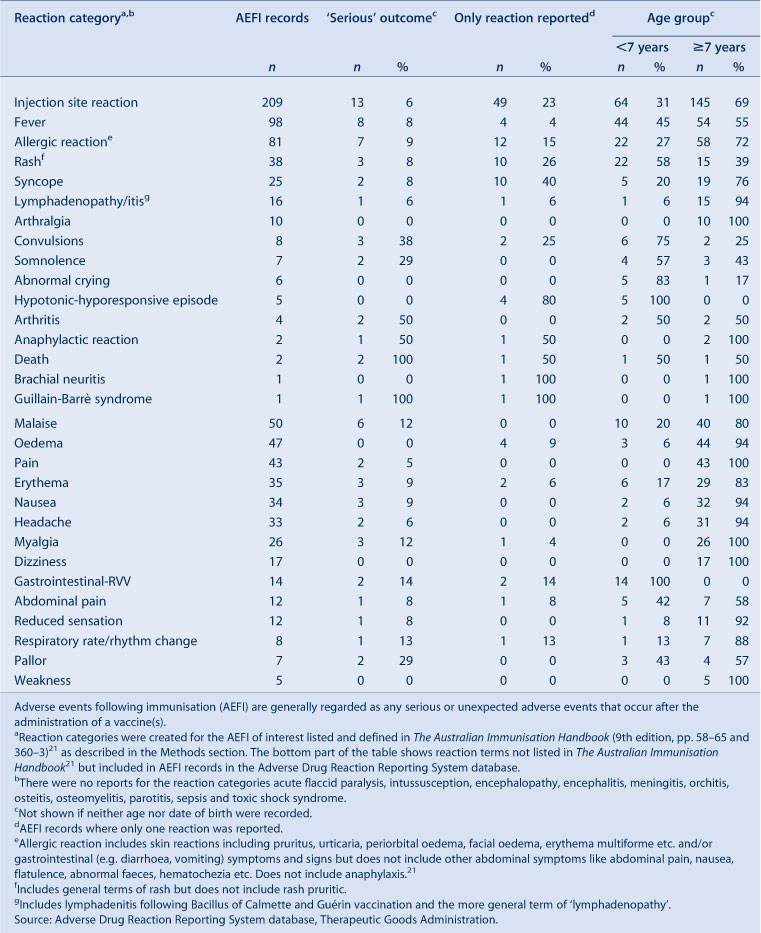

Reactions

The distribution and frequency of reactions listed in AEFI records for 2011 are shown in Table 2. The most frequently reported adverse events were injection site reaction (47%), fever (22%), allergic reaction (18%), malaise (11%), oedema and pain (10% each), and rash, erythema and nausea (8% each) (Table 2).

|

Of the total 209 cases of injection site reaction, 64 (31%) were children aged less than 7 years and 145 (69%) were in people aged 7 years and over. The most commonly suspected vaccines for children aged less than 7 years related to injection site reaction were: DTPa-IPV (n = 36), 13vPCV (n = 19), MMR (n = 10), hexavalent vaccine (n = 5) and 7vPCV (n = 3). For those aged 7 years and over, the most commonly suspected vaccines related to injection site reaction were: 23vPPV (n = 99; this included two reports in the 12–17-year age group, 26 reports in the 18–64-year age group and 71 reports in adults aged 65 years and over), seasonal influenza vaccine (n = 36; one report in the 12–17-year age group, 15 in the 18–64-year age group and 20 in adults aged 65 years and over) and dTpa (n = 26; seven reports in the 12–17-year age group, 14 in the 18–64-year age group and five in adults aged 65 years and over) either given alone or co-administered with other vaccines.

There were 25 reported cases of syncope during 2011 compared with only four cases reported in 2010. Five cases were reported in children aged less than 7 years following administration of DTPa-IPV-containing vaccines. Twenty cases were reported in people aged 7 years and over following receipt of dTpa vaccine (n = 9), HepB (n = 3), HPV (n = 6) and 23vPPV/seasonal influenza vaccine (n = 2): the majority were in 12–17-year olds (n = 13, 65%).

There were five reports of hypotonic-hyporesponsive episodes reported from children aged less than 7 years. Two reports were following co-administration of hexavalent/pneumococcal conjugated vaccine/rotavirus vaccines, one case was following co-administration of hexavalent and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, and one case was following administration of hexavalent and pneumococcal conjugate vaccine each.

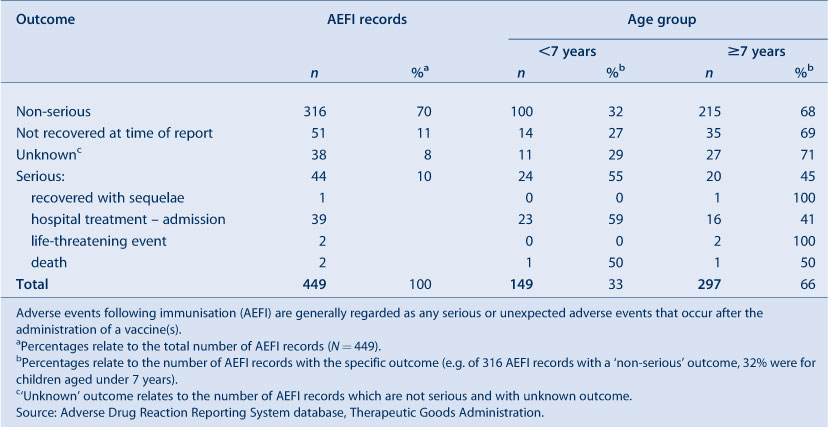

Severity of outcomes

Ten percent (n = 44) of events were defined as ‘serious’ (i.e. recovery with sequelae, requiring hospitalisation, experiencing a life-threatening event or death); similar to that observed in 2010. Numbers of reported events and events with outcomes defined as ‘serious’ are shown in Table 3.

|

Eleven percent of records were recorded as ‘not fully recovered’ at the time of reporting (Table 3); 35% of these were following receipt of 23vPPV, 25% following DTPa-IPV-containing vaccines and 24% following seasonal influenza vaccines. Information on severity could not be determined for 8% of records (n = 38); 42% of these were following receipt of 23vPPV and 37% following DTPa-IPV-containing vaccines. Of those without information describing severity, the most commonly reported adverse reaction was injection site reaction (61%, n = 23).

The reactions recorded as ‘serious’ were: injection site reaction (n = 13), fever (n = 8), allergic reactions (n = 7), febrile convulsions (n = 3), diarrhoea/vomiting (n = 2), syncope (n = 2), one case each of Guillain-Barrè syndrome and anaphylaxis and two reported deaths.

There were two cases of anaphylaxis; one was coded as serious and occurred 5 minutes post first dose of seasonal influenza vaccine. The other case of anaphylaxis, not coded as serious, was following co-administration of dTpa and HepB vaccine.

The only reported case of Guillain-Barrè syndrome was in an adult following co-administration of seasonal influenza vaccine (Fluvax®) combined HepA/B formulation (Twinrix®). The onset date was approximately 6 weeks post-vaccination.

Two deaths were recorded as temporally associated with receipt of vaccines. One was a 4-month old infant who had received hexavalent, 13vPCV and rotavirus vaccine 3 days prior to death. The cause of death was recorded as sudden infant death syndrome. The other reported death was a 51-year old with motor neurone disease who died 4 days after receiving the seasonal influenza vaccine. He developed flu-like illness after vaccination and had a cardiac arrest. The cause of death was documented as complications of motor neurone disease.

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

In 2011, the pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (7vPCV and 13vPCV) were suspected of involvement in 73 AEFI records (42 for 13vPCV and 31 for 7vPCV) for people aged less than 7 years with 10 cases coded as serious (six for 7vPCV and four for 13vPCV). Ninety percent of the 7vPCV reports were from the first half of the year and all the 13vPCV cases were vaccinated between June 2011 and December 2011. The reporting rates were 29.4 per 100 000 doses for 13vPCV and 19.5 per 100 000 doses for 7vPCV (Table 1). The rate for 7vPCV was higher in 2011 than in 2010 (10.8) and 2009 (7.8). All the 7vPCV vaccines were co-administered with hexavalent and rotavirus vaccines while in the case of 13vPCV, 50% (n = 21) of cases were 13vPCV administered alone, under the catch-up program offered to children aged between 12 months and 35 months.

The distribution of reaction types for both 7vPCV and 13vPCV are presented in Figure 5. 7vPCV was not recorded as the only suspected vaccine for any reported reaction category. The most frequently reported reactions for 7vPCV were fever and vomiting/diarrhoea (n = 10, 32% each) and allergic reactions and rash (n = 7, 23% each).

13vPCV was the only suspected vaccine in 21 (50%) records. There were 19 (45%) reports of injection site reaction; nine (21%) of fever; eight (19%) of rash; five (12%) of allergic reactions; one case of syncope and one reported death following co-administration of hexavalent, 13vPCV and rotavirus vaccine.

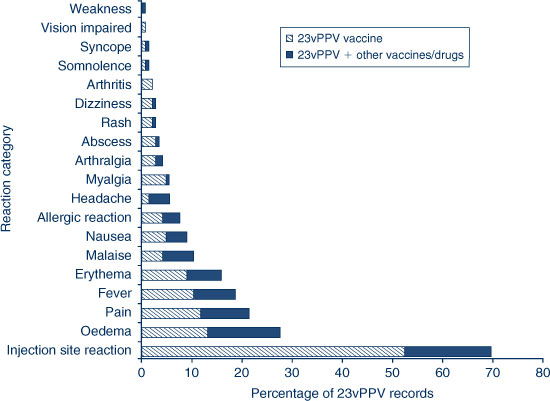

Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (23vPPV)

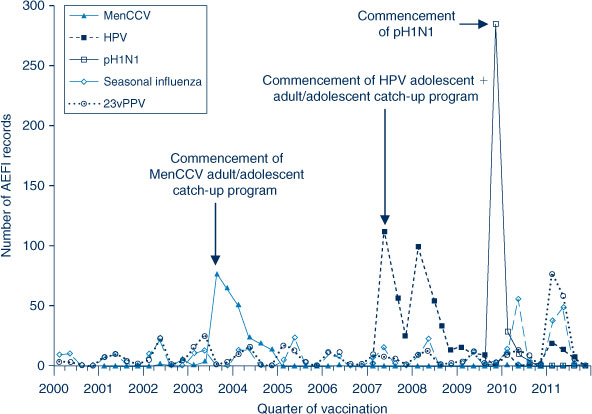

There were a total of 145 records for 2011 where 23vPPV was listed as a suspected vaccine. Five records were from those aged less than 18 years (three in the 0–6-year age group and two in the 12–17-year age group). There were 140 AEFI records for adults aged 18 years and over where 23vPPV was listed as suspected of involvement in the reported adverse event with four cases coded as serious and 97 reports of injection site reaction. Of the 140 cases, 108 cases were reported from older adults (aged 65 years and over). Using the 2009 estimate of the number of doses of 23vPPV administered to people aged 65 years and over (n = 110 899),23 the AEFI reporting rate was 97.4 per 100 000 doses; this was four times higher than in 2010 (23.4 per 100 000 doses). The distribution of reaction types for 23vPPV is presented in Figure 6. The most commonly reported reaction was injection site reaction (n = 101), oedema (n = 40), pain (n = 31), fever (n = 27), erythema (n = 23), malaise (n = 15) and nausea (n = 13).

|

Figure 7 shows the initial increase in reports following 23vPPV in 2011 (by week of report) until 25 March, which was much greater than the historical average. These initial reports triggered a national investigation, which led to a batch recall on 25 March, which then resulted in stimulated reporting.

|

Discussion

There has been a slight increase in the total number of AEFI records and population-based reporting rates in 2011 compared with the corresponding period in 2010. Compared with 2010, there was a large decline in AEFI reporting following vaccination with seasonal influenza vaccine and pH1N1 influenza vaccines. The reduced reporting of AEFIs related to seasonal influenza vaccine is notable and suggests that recommendations for not using the CSL vaccine (Fluvax®) in young children (aged under 10 years)22,23 have decreased AEFIs at a population level.

An increase was observed in reporting rates per 100 000 doses of certain vaccines and age groups as shown in Table 1. By age group, reporting rates per 100 000 doses were higher in 2011 compared to 2010 for all age groups, but the increase was statistically significant in children aged 2 to less than 7 years (31.5 vs 16.2) and 12–17-year olds (19.4 vs 6.7). The increase in reporting of AEFIs in children aged 2 to less than 7 years in 2011 is primarily because of increased reporting of injection site reactions following vaccination with DTPa-IPV-containing vaccines and 13vPCV. Data from the clinical studies of Prevenar 13® demonstrated similar rates of injection site reactions when comparing 7vPCV with 13vPCV, with an increase in injection site reactions following the fourth dose of either 7vPCV or 13vPCV (in the second year of life) compared with earlier doses in infancy. A similar trend was also observed for other systemic reactions.24 From October 2011 children aged between 12 and 35 months who had completed a primary pneumococcal vaccination course with 7vPCV have been eligible to receive a free supplementary dose of Prevenar 13®.11 The increased reporting rate of injection site reactions for 13vPCV may be in part because it is being given as a fourth dose of a PCV vaccine at an older age. The higher number of reports following 13vPCV might also be attributed to the ‘Weber effect’25 which describes increased reporting frequently observed following the introduction of new vaccines.

A significant increase in reporting rates was also observed in adolescents, mainly due to injection site reactions following administration of dTpa vaccine. One suggested hypothesis for the mechanism of injection site reactions is an ‘Arthus reaction’ caused by the presence of high levels of pre-vaccination IgG antibody in the vaccinees.26,27 Possible causes of higher pre-vaccination antibody levels include immunity induced from natural infection in the pertussis epidemic from 2008, which was notable for high notification rates in pre-school and primary school-aged children,28 as well as the earlier age of administration of the pre-school DTPa-IPV booster and the adolescent booster (at age 12 years, compared with age 15 years) that has occurred in response to program changes in recent years.29

There was a higher than expected number of injection site reactions detected following administration of the 23vPPV vaccine in NSW. Reporting rates per 100 000 doses were four times higher in all AEFIs (97.4 in 2011 vs 23.4 in 2010) following vaccination with 23vPPV in the elderly population aged 65 years and over. This increase may be due to larger numbers of people receiving second doses following the commencement of the nationally funded vaccine in 2005, and related increased marketing of a second dose leading to increased use of 23vPPV in early 2011. However, the current method of estimating the number of doses administered does not allow the detection of changes in vaccinations by year and cannot distinguish between first and subsequent doses. In response to the continued increase in reports of severe injection site reaction reports, in April 2011 the TGA issued advice to health professionals not to administer a second or subsequent dose of Pneumovax 23® vaccine.13 An expert multidisciplinary working group was convened to investigate all reports of injection site reaction following 23vPPV. Revised recommendations regarding which patients should be re-vaccinated under the National Immunisation Program was provided in December 2011, with re-vaccination no longer recommended for those aged 65 years and over without predisposing medical conditions.14

We cannot exclude that the higher overall numbers of reports and reporting rates in 2011 may also be a result of an increased propensity by immunisation providers to report due to the heightened awareness of AEFIs following influenza vaccine safety issues in 2010. Increased reporting may also reflect changes in the proportion of reports transmitted from public health units to the NSW Ministry of Health, and thence to the TGA.

Conclusion

The total number of AEFIs reported in 2011 was slightly higher compared with the same period in 2010, mainly due to reports of injection site reactions. Increases in reports in infants were related to the introduction of 13vPCV onto the schedule from July 2011, particularly including the supplementary booster dose for children aged 12–35 months. Increases in the 2 to less than 7 year age group were related to the DTP-IPV vaccine, and follow an increasing trend since 2009. There was also an increase in the 12–17-year age group associated with dTPa. Increases in the 65 years and over age group were associated with injection site reactions following administration of 23vPPV, many of which may have been second doses. If a real increase in injection site reaction incidence has occurred following pertussis vaccines, one possible explanation for children and adolescents is higher pre-vaccination antibody levels, due to the recent pertussis epidemic and possibly also earlier receipt of the pre-school and adolescent booster. There may also be a greater propensity by vaccine providers to report in 2011 due to the heightened awareness of AEFIs following influenza vaccine safety issues in 2010.

The majority of AEFIs reported to the TGA were mild transient events and the data reported here are consistent with an overall high level of safety for vaccines included in the National Immunisation Program schedule.

Acknowledgments

The National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance is supported by the Department of Health and Ageing, the NSW Ministry of Health and The Children’s Hospital at Westmead.

References

[1] Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) c/o World Health Organization. Definition and Application of Terms for Vaccine Pharmacovigilance: Report of CIOMS/WHO Working Group on Vaccine Pharmacovigilance. 2012. Available at: http://www.cioms.ch/frame_vaccine_pharmacovigilance.htm (Cited 18 May 2012).[2] Lawrence G, Boyd I, McIntyre P, Isaacs D. Surveillance of adverse events following immunisation: Australia 2002 to 2003. Commun Dis Intell 2004; 28 324–38.

[3] Lawrence G, Boyd I, McIntyre P, Isaacs D. Annual report: surveillance of adverse events following immunisation in Australia, 2005. Commun Dis Intell 2006; 30 319–33.

[4] Lawrence G, Gold MS, Hill R, Deeks S, Glasswell A, McIntyre PB. Annual report: surveillance of adverse events following immunisation in Australia, 2007. Commun Dis Intell 2008; 32 371–87.

[5] Lawrence GL, Boyd I, McIntyre PB, Isaacs D. Annual report: surveillance of adverse events following immunisation in Australia, 2004. Commun Dis Intell 2005; 29 248–62.

[6] Lawrence GL, Aratchige PE, Boyd I, McIntyre PB, Gold MS. Annual report on surveillance of adverse events following immunisation in Australia, 2006. Commun Dis Intell 2007; 31 269–82.

[7] Menzies R, Mahajan D, Gold MS, Roomiani I, McIntyre P, Lawrence G. Annual report: surveillance of adverse events following immunisation in Australia, 2008. Commun Dis Intell 2009; 33 365–81.

[8] Mahajan D, Cook J, Mclntyre P, Macartney K, Menzies R. Annual report: surveillance of adverse events following immunisation in Australia, 2010. Commun Dis Intell 2011; 35 263–80.

[9] Mahajan D, Campbell-Lloyd S, Roomiani I, Menzies R. NSW Annual Adverse Events Following Immunisation Report, 2009. N S W Public Health Bull 2010; 21 224–33.

| NSW Annual Adverse Events Following Immunisation Report, 2009.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar |

[10] Mahajan D, Campbell-Lloyd S, Cook J, Menzies RI. NSW Annual Report Describing Adverse Events Following Immunisation, 2010. N S W Public Health Bull 2011; 22 196–208.

| NSW Annual Report Describing Adverse Events Following Immunisation, 2010.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar |

[11] Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Immunise Australia program. Pneumococcal Disease: Recent changes to pneumococcal vaccine for children Program providing a supplementary dose of Prevenar 13®. Available at: http://immunise.health.gov.au/internet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/immunise-pneumococcal (Cited 2 May 2012).

[12] Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Therapeutic Goods Administration. Pneumovax® 23: Recall of vaccine batch N3336. 25 March 2011. Available at: http://www.tga.gov.au/safety/alerts-medicine-pneumovax-110325.htm (Cited 2 May 2012).

[13] Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Therapeutic Goods Administration. Pneumovax 23 – Recommendation about revaccination. 18 April 2011. Available at: http://www.tga.gov.au/safety/alerts-medicine-pneumovax-110416.htm (Cited 2 May 2012).

[14] Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Immunise Australia program. Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) Statement – Updated recommendations for revaccination of adults with 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (23vPPV), Pneumovax 23®. December 2011. Available at: http://immunise.health.gov.au/internet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/pneumo23-atagi-statement-cnt.htm (Cited 31 May 2012).

[15] National Health and Medical Research Council. The Australian Immunisation Handbook. 8th ed. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2003.

[16] National Health and Medical Research Council. The Australian Immunisation Handbook. 9th ed. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2008.

[17] Uppsala Monitoring Centre. WHO Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring. 2009. Available at: http://www.who-umc.org/ (Cited 1 February 2009).

[18] Brown EG, Wood L, Wood S. The medical dictionary for regulatory activities (MedDRA). Drug Saf 1999; 20 109–17.

| The medical dictionary for regulatory activities (MedDRA).Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | 1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3cXltleksQ%3D%3D&md5=fbd2039d4e9b75088a0dc67967510a3dCAS |

[19] Zhou W, Pool V, Iskander JK, English-Bullard R, Ball R, Wise RP, et al. Surveillance for safety after immunization: Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS)–United States, 1991-2001. MMWR Surveill Summ 2003; 52 1–24.

[20] Australian Bureau of Statistics. 31010DO002_201006 Population by Age and Sex, Australian States and Territories, Jun 2010. Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2010. Released at 11:30 am (Canberra time) 21 December 2010.

[21] Centre for Epidemiology and Research. Summary report on adult health from the NSW Population Health Survey, 2009. Sydney: NSW Department of Health; 2010.

[22] Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. TGA. Seasonal influenza vaccines: safety advisory. 11 March 2011. Available at: http://www.tga.gov.au/safety/alerts-medicine-seasonal-flu-110310.htm (Cited 1 June 2012).

[23] Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Immunise Australia program. Chief Medical Officer advice: Seasonal influenza vaccination. 7 March 2011. Available at: http://www.immunise.health.gov.au/internet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/immunise-cmo (Cited 1 June 2012).

[24] Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian Public Assessment Report for Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Conjugate Vaccine (Prevenar 13®). Available at: http://www.tga.gov.au/pdf/auspar/auspar-prevenar13.pdf (Cited 1 June 2012).

[25] Simon LS. Pharmacovigilance: towards a better understanding of the benefit to risk ratio. Ann Rheum Dis 2002; 61 ii88–9.

[26] Rennels MB. Extensive swelling reactions occuring after booster doses of Diphtheria-tetanus-Acellular Pertussis vaccines. Seminars in Pediatr Infect Dis J 2003; 14 196–8.

[27] Liese JG, Stojanov S, Zink TH, Froeschle J, Klepadlo R, Kronwitter A., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of Biken acellular pertussis vaccine in combination with diphtheria and tetanus toxoid as a fifth dose at four to six years of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2001; 20 981–8.

| Safety and immunogenicity of Biken acellular pertussis vaccine in combination with diphtheria and tetanus toxoid as a fifth dose at four to six years of age.Crossref | GoogleScholarGoogle Scholar | 1:STN:280:DC%2BD3Mrmt1Oitw%3D%3D&md5=17e64c48a5e511332858b5dec712b5d3CAS |

[28] NNDSS Annual report writing group Australia's notifiable disease status, 2009: Annual report of the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System. Commun Dis Intell 2011; 35 61–131.

[29] Hull B, Dey A, Mahajan D, Menzies RI, McIntyre PB. Immunisation coverage annual report, 2009. Commun Dis Intell 2011; 35 132–48.

* The Public Health Act 2010 (NSW) (http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/phact/)

The Public Health Act 2010 (NSW) was passed by the NSW Parliament in December 2010 and commenced on 1 September 2012. The Public Health Regulation 2012 was approved in July 2012 and commenced, along with the Public Health Act 2010 (NSW), on 1 September 2012. The objectives of the Regulation are to support the smooth operation of the Act. The Act carries over many of the provisions of the Public Health Act 1991 (NSW) while also including a range of new provisions.