Recruiting participants via social media for sexual and reproductive health research

Jacqueline Coombe A * , Helen Bittleston

A * , Helen Bittleston  A , Teralynn Ludwick

A , Teralynn Ludwick  A , Megan S. C. Lim

A , Megan S. C. Lim  B , Ethan T. Cardwell A , Linde Stewart

B , Ethan T. Cardwell A , Linde Stewart  A , Louise Bourchier

A , Louise Bourchier  A , Amelia Wardley

A , Amelia Wardley  A , Jane L. Goller

A , Jane L. Goller  A , Cassandra Caddy A and Jane S. Hocking

A , Cassandra Caddy A and Jane S. Hocking  A

A

A

B

Abstract

Recruiting participants is a vital component of social research. Finding the right people (and the right number of them) at the right time to participate in your study can make or break its success; it can also challenge research budgets and requires considerable flexibility. Online recruitment strategies are becoming increasingly popular ways to recruit to both qualitative and quantitative studies. In this paper, we detail our experiences of using social media, primarily Meta platforms Facebook and Instagram, to recruit participants for our sexual and reproductive health research. Here, we provide a practical guide to using social media to recruit participants, and include examples throughout from our own research. We outline our triumphs and pitfalls in using this recruitment strategy, the challenges we have faced and the lessons we have learnt. In doing so, we hope to provide useful guidance for others wishing to use social media to recruit to their research studies.

Keywords: Australia, internet, methodological issues, online survey, participant recruitment, public health, qualitative interviews, sexual health research.

Introduction

Recruiting participants is a vital component of social research. Finding the right people (and the right number of them) at the right time to participate in your study can make or break its success. It can also challenge research budgets and requires considerable flexibility. Recruitment strategies over the past decade have changed substantially. Although traditional recruitment methods, such as random-digit dialling or door-knocking, are still in use,1 increasingly, online recruitment is being utilised. This includes placing paid advertisements (ads) on social media platforms, which are widely used in Australia.2 Recruitment via social media is typically quite successful, with a recent systematic review finding that social media recruitment performed as well as, or better than, other strategies.3

Alongside the obvious benefit of advertising your study in a place where most of the population frequent, using social media for recruitment has benefits for the researcher. It is flexible and budget friendly, and it is possible to ‘give it a go’ without a large budget or time commitment. Theoretically, it can also help to recruit ‘hard to reach populations’.4 Although publications reporting on the use of social media for recruitment – including for sexual and reproductive health research (see for example5,6) – are increasing, there is little practical guidance regarding how to use social media to recruit participants.

In this paper, we detail our experiences using social media, primarily Facebook and Instagram, to recruit participants for sexual and reproductive health research. We outline the types of studies in which we used social media recruitment, challenges faced and lessons learnt. As a team of experienced sexual and reproductive health researchers with expertise conducting a range of research methods with diverse population groups, our goal is to provide a practical guide to using social media to recruit for sexual and reproductive health research.

Using social media to recruit: a practical guide

We outline the main steps we have undertaken when recruiting for study participants via Meta platforms, Facebook and Instagram, and provide examples spanning a range of sexual and reproductive health topics (e.g. contraceptive use, sexual behaviour and sexually transmitted infections), varied study designs (online surveys, qualitative interviews and co-design workshops) and engaging various populations of interest (e.g. young people, people of reproductive age and older adults (≥60 years)). See Table 1 for a summary of our studies. Note that we use social media for recruitment only; data collection itself occurs once the potential participant clicks through to the survey instrument hosted elsewhere (for example using Qualtrics or REDCap survey software), or provides their contact details for the researcher to then get in touch to organise an interview.

| Study (including design and completion time) | Target population | Social media used | Meta ad or boosted post? | Recruitment time period | Cost for using the social media platform (AUD) | Total participants recruitedA | Participant incentives | Relevant publications | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Per participant | |||||||||

| The LARC Project. Cross-sectional online survey, 20 min | Women aged 18–45 years, living in Australia | Facebook and Instagram | Boosted post | 4 weeks 24 August−20 September 2022 | $374.00 | $0.21 | 1745A | Prize draw 10 × $20 gift cards | Forthcoming | |

| Sexual and Reproductive Health during COVID-19. Four online cross-sectional surveys, including cohort study, 30 min | People living in Australia | Facebook and Instagram | Meta ad | April 2020 June 2020 August 2020 December 2020 | $165.00 $385.00 $549.95 $550.00 | – | 4019A | None | 7–13 | |

| Bacterial Vaginosis in postmenopausal women. Cross-sectional online survey, 30 min | Women aged >50 years living in Australia | Meta ad | 8 weeks 8 July−8 September 2021 | $1205.00 | $1.79 | 675 | None | 14 | ||

| Sex, Drugs, Rock n Roll. Annual cross-sectional online survey, 20–25 mins | Young people aged 15–29 years living in Victoria | Facebook and Instagram | Meta ad | ~6 weeks, annually | $200.00–$500.00 per year | ~$3.00 | ~1000/year | Prize draw, chance to win $250 | 15–20 | |

| SHAPE2: Older adults sexual health. Cross-sectional online survey, 15–20 mins | People ≥60 years in Australia | Meta ad | 4 weeks 8 May−7 June 2021 | $400.00 | ~$1.00–1.50 | ~300 | None | 21,22 | ||

| Young people’s sexual health. Cross-sectional online survey, 15–20 mins | People aged 16–29 years in Australia | Facebook and Instagram (mostly Instagram) | Meta ad | 7 weeks 2 May−21 June 2022 | $968.00 | $0.43 | 2260A | Prize draw 5 × $100 gift cards | 23–25 | |

| What young people want in an online STI service. Cross sectional online survey, 15–20 mins | People aged 16–29 years living in Victoria | Facebook and Instagram | Meta ad and boosted post | 4 weeks September 16–October 15 2022 | $431.00 | $0.48 | 905 | Prize draw 5 × $100 gift cards | 26–28 | |

| Co-designing an online STI Service (Test it). Online survey 15–20 mins, and participatory co-design workshops. 2 × 3 h | People aged 16–29 years living in Victoria | Facebook and Instagram | Meta ad and boosted post | 20 November 2022–27 April 2023 | $204.56 | $1.35 | 152 | $20 for initial survey completion, $200 for workshop completion | 29 | |

| Men and contraceptive use. Qualitative Interviews 35–40 mins | Heterosexual men aged 18–30 years without children | Boosted post | 5 weeks 1 November 2022–6 December 2022 | $128.00 | $6.73 | 19A | $25 gift voucher | Forthcoming | ||

| Coping with COVID. Longitudinal cohort study, 20 mins | People aged 15–29 years living in Australia | Meta and survey panel | Meta ad | March–July 2020 | $3151.08 | $3.77 | 2000 (835 from Meta, 1157 from panel) | Chance to win 1 of 5 × $50 vouchers | 30,31 | |

Please note, our studies were undertaken in Australia; laws and regulations regarding virtual advertisements may vary depending on your location. As social media platforms, and the people who use them, are constantly changing, we suggest doing your own research about advertising on the respective platforms prior to recruiting in this way. Likewise, including recruitment via your chosen social media platforms in your local Human Research Ethics Committee is also important to ensure adherence to your local ethical requirements.

Step 1: determine the appropriate account to use for management of recruitment advertisements

Depending on the social media platform, you will likely need to set up an account to manage ads. We suggest creating an account for the study or research team (see here for instructions for Meta: https://www.facebook.com/help/453789191486304). This creates a central location for you and/or your team to manage the performance of your advertisements without the direct use of personal accounts (although you do need a personal account to set up the study/research team account). For much of our team’s research, we used a specific Sexual Health Unit Facebook page created to facilitate recruitment. This page is managed by multiple team members (through personal accounts), and is associated with an email address set-up via our institution accessible to all members of the research team. This can be important for legitimacy of your study, and to depersonalise any negative responses you may receive about your research (see below for further discussion about this). If you are affiliated with an organisation – such as a university, as is the case for us – it is best to check with your media team regarding policies around the set-up of Meta accounts for research groups.

Step 2: creating advertisement posts

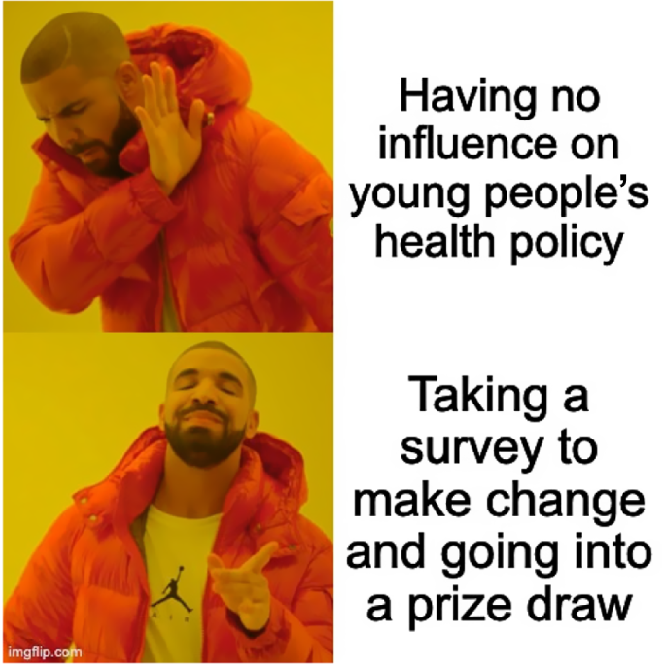

Meta allows for a wide range of creative content, including stock images, infographics, memes and videos. Our team typically use the form of a short blurb accompanying an image, including a link to either the survey or further information about the study for potential participants. Images chosen will vary depending on the study topic and target audience, and more than one image may be used across different ads. The content of the post is often very short and descriptive, outlining briefly what the study is about, what participation entails and who is eligible to participate. For an example of what our ads typically look like, see Fig. 1 and Box 1.

| Box 1.Creating different types of advertisement posts |

| Sex, Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll (SDRR) survey advertisements: SDRR is an annual health and wellbeing survey of young people aged 15–29 years in Victoria. Since 2015, a combination of stock images, infographics and meme-based images were used to recruit participants via social media. Stock images included images of young people, and were accompanied by a short blurb. For example: Want the chance to win a gift voucher? Complete this quick survey about drugs, sexual health, alcohol and other behaviours among young Victorians. Meme-based images (see Fig. 2 for an example) were used to appeal to younger age groups. As SDRR is an annual survey, a series of infographic images/videos reporting on findings from the previous iteration were also used. For example: Can chlamydia be diagnosed by a urine test? In 2022 52% of participants got this question wrong. Have your say in 2023. Each year, we monitor the popularity of different ads. For example, in 2021, memes (such as Fig. 2) were particularly popular among young men. Because this group is typically underrepresented in our survey, we increased spending on meme ads. However, in 2023, infographic ads outperformed memes, highlighting the importance of updating and monitoring performance of creatives. |

Step 3: determine the ad type, budget and timeframe

Across our studies, we used two methods of advertising via Meta: (1) Meta ads, created using Meta’s Ads Manager; and (2) boosted posts (defined below). Since our most recent advertising campaign, Meta has also introduced Ad Centre, which may be used to create and manage advertising. Meta ads allowed for considerable flexibility for customisation, including allowing users to choose different ad placements, objectives, manage demographic-specific targeting and manage performance (see: https://www.facebook.com/business/help/317083072148603). As a quicker and often simpler alternative, we sometimes opted to ‘boost’ a newly created or existing post on the Sexual Health Unit Facebook page (paying money for the post to be shown to a predefined audience for a specific period of time; Box 2).

| Box 2.Example of using a boosted post vs Meta ad |

| The LARC (long-acting reversible contraception) project: Aimed to understand the knowledge and information needs of potential and current intrauterine device and contraceptive implant users (collectively referred to as LARC). An online survey was conducted with women and people with female reproductive organs who were aged 18–45 years and currently living in Australia. Boosted ads were used to recruit for this study. A post was created and boosted for 7 days. At the end of this time period, either the same ad was boosted again, or a new ad (often using a different image, but the same text) was posted and boosted. In this way, recruitment could be monitored and ads targeted to specific participants (for example, women aged >30 years only). Each time, a small budget (between AUD50 and 100) was allocated to the boost. |

| Young people’s sexual health: Meta Ads Manager was used to create advertisements for a survey exploring young people’s sexual health. Prior to creating the ad, a budget, start and end date/time was established. An audience was selected (in this case, anyone aged 16–29 years in Australia). Regarding the ad content, an image containing information about the study was created and uploaded (see Fig. 1). Further information about the study, including a URL and researcher contact information, was included as ‘primary text’, which appeared above the image. Below the ad a ‘call to action’ button was inserted with the text ‘Learn More’, which took potential participants to the online survey landing page. |

Regardless of which advertising method you choose, you will need to consider the budget and the length of time you would like to allocate the advertisement based on your recruitment goals. Flexibility regarding budget and timeframes are needed. In some of our studies the recruitment goal was reached far more quickly and with a smaller budget than anticipated. In others, more time and money was required to reach sufficient recruitment. Our budgets ranged from AUD128 to AUD1200 (see Table 1; Box 3).

| Box 3.Examples of budget and recruitment considerations |

| The LARC Project: Using a ‘boosted’ post (rather than a Meta Ad), potential participants were invited to complete the online survey by clicking on a link. Ten AUD20 gift vouchers were offered as incentives to survey participants. It was anticipated that 500 people would complete the survey, and that it would cost AUD1500 across 2 months to recruit them. In total, 1745 people completed the survey during a period of 4 weeks in 2022. The total cost was AUD374. |

| Sexual and Reproductive Health during COVID-19, Survey 4: This repeated cross-sectional survey explored the impact of COVID-19 on the sexual and reproductive health of Australians. We had successfully used Meta ads for recruitment to the earlier three iterations of the survey, although we had noticed engagement decreasing over time. Based on our earlier experience, we anticipated it would cost approximately AUD500 to recruit >500 people in under 3 weeks. However, a total spend of AUD550 resulted in only 152 new survey respondents over 3.5 weeks. It is unclear why engagement was low, although we hypothesised that it may have been related to public fatigue with and/or mistrust regarding COVID-19-related research. This was supported by commenters on the ad that questioned the researchers’ motivations. We decided to discontinue advertisements despite not achieving the desired sample. |

Most of the studies we report on here offered an incentive for participants, typically entry into a prize draw (online surveys) or a gift voucher (qualitative research). Although offering incentives can support recruitment, in the context of social media recruitment, we have little evidence of the impact of the incentive on an ad’s success or failure. We recommend offering incentives as you would if you were recruiting via traditional methods, and of course, if you have the budget for it.

Step 4: publishing and monitoring your ad

After publishing your ad, it is important to actively monitor it. This will be important for you to understand the ad metrics (e.g. the number of views and clicks on your ad) and how they compare to the actual number of people who are completing (or contacting you about) your study. Doing so allows you to make adjustments to (hopefully) improve recruitment. We were also able to adjust the content of our original advertisement or create new ones to reach populations that were underrepresented (although, some sub-populations proved hard to reach – see lessons learned below; Box 4).

| Box 4.Adjusting advertisements to target specific population groups |

| SHAPE2: Older adults’ sexual health online survey: We published a Facebook ad to be displayed to users aged ≥50 years (≥60 years was not an option) in Australia. By monitoring data in Meta ad manager and Qualtrics survey software, we identified that some states/territories were underrepresented, and that there were fewer women responding than men. To address this, we ran a second ad that was only displayed to women, and we adjusted the geographical settings on the first ad to only be shown to the states/territories where we sought to increase uptake. These strategies were effective at increasing participation among the desired demographics. |

| Testit: In some cases, it may be hard to know how to adjust the graphic to attract a particular audience. In recruiting young people (aged 16–29 years) to participate in a survey on preferences for online STI testing, we tried adjusting the ad settings to attract more respondents from rural and regional Victoria. Unfortunately, the geographic targeting within the ad settings had limited effect. |

You will also need to monitor the ad for comments and your study/research group Facebook page (see Step 1) for direct messages. Depending on the nature of the comments or direct messages, you may decide to disable comments for the post or block specific individuals from seeing posts from your page (Box 5).

| Box 5.Dealing with comments and messages on your ads |

| How you deal with comments and messages on your ads is likely dependent on the type of message or comment you receive. We found some people use comments to ‘tag’ others or request further information about the study. In these situations, providing any further information is relatively straightforward and innocuous. Our research team have also had experiences where people have commented, or sent inflammatory or abusive messages to the researchers about the study. Such comments and messages have the potential to offend or deter other social media users from participating in the study. They can also have the unfortunate side-effect of showing your ad to other, like-minded people, and can exacerbate the situation (see our section below on challenges and lessons learnt for more on this). There is no recipe for how best to respond to such comments. In such circumstances, our team has discussed the issue and responded by either ignoring or deleting the comments, turning the option for comments off for the specific ad, and in some cases, removing the ad early and reposting at a later date (with comments turned off). |

Challenges we have faced and lessons we have learnt

Although using Meta to recruit participants for our research has been incredibly useful, there are some challenges when recruiting in this way. In this section we highlight some of these challenges, and lessons learnt.

Meta ads system is somewhat opaque and designed for commercial advertising rather than research

To the inexperienced user, Meta ads manager can be a mysterious and oft-changing platform with little troubleshooting support, meaning that it is sometimes difficult to retrospectively find data relating to your ads. It can be unclear how the Meta algorithm works, and once posted there is little information on who Meta chooses to show your ad to and why those specific people have been chosen to view it. Relatedly, it is impossible to know who has seen your ad and who has shared it (and where they have shared it). Negative comments clearly impact who is seeing your ad; Meta is set up for commercial advertising and not study recruitment, meaning that it may continue to show your ad to groups of people who may interact with it negatively, in the mistaken view that all interaction with your ad is good interaction.

Limitations to how specifically you can target your advertisement

We have had varied experiences with recruiting particular populations, and in our experience, it is difficult to predict which populations will participate and which will not (even with adjusting advertising settings to target particular groups). Upon reviewing the characteristics of our study participants, we have found some populations were underrepresented, including heterosexual men, people living in states with smaller populations (e.g. ACT, NT), Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples, and people from culturally and linguistically diverse communities. Conversely, we have had success recruiting older adults (aged ≥60 years), women, younger people and people who identify as LGBTQIA+ to our research via social media.

Quality control measures

Multiple responses from the same people, or responses that appear to be completed by artificial intelligence are also difficult to manage. We have had experiences where participants have completed a survey multiple times (presumedly with the goal of increasing their chances of winning the prize draw), or where they attempt to participate in an interview when they clearly do not meet the inclusion criteria (e.g. they do not live in Australia). Artificial intelligence responses are unfortunately often difficult to discern; the researcher is left with the decision to not include the data in their analysis, or include it despite having concerns about its quality. We strongly suggest using the appropriate settings in your data collection tool (for example, Qualtrics Survey Software or REDCap) to avoid or flag artificial intelligence responses, duplicate responses, or responses from people who do not meet your criteria (e.g. completing the survey outside Australia) where possible. Regular monitoring of data during collection is also important for identifying any concerns with data quality early.

Other platforms for recruitment

Although we have utilised other social media platforms for recruitment, including paid ads on Snapchat, YouTube and TikTok, they were all unsuccessful. These platforms also require the creation of videos, which are more time and resource intensive than static images. We have often had little budget for the creation of this content, relying on our own (rudimentary) marketing skills to create recruitment ads. Budgets with scope for marketing professionals and video creation would be beneficial, but are not always realistic or possible.

We have also used Reddit and X (formerly Twitter) for recruitment by posting an (unpaid) ad on these platforms. These platforms require natural reach, relying on an existing account with a large following, or posting in appropriate groups to be successful. Although we do not have any metrics, our impression based on our experience is that these platforms have become less usable for recruitment over time, attracting more fake responses than responses from genuine participants.

Social media platforms that target specific population groups – including, for example, dating apps or WeChat – may be useful platforms for future recruitment. We do not have experience using these platforms, but these are certainly avenues for future exploration, and have been used by others for recruitment (see Witkovic et al. for example32).

Conclusion

In our experience, social media is an important recruitment tool to consider when seeking participants for sexual health projects. Although there are pitfalls and challenges overall, we have found social media a largely inexpensive and convenient method of recruitment, albeit one that requires ongoing monitoring and adaptability on behalf of the researcher. Regardless of study type, we have largely successfully recruited participants to complete our studies. Although these have typically been for a single data collection event (e.g. one interview or one survey), we have also had some success in recruiting and retaining participants recruited via social media over time. The usability of social media for recruiting participants for more complex study designs (e.g. randomised controlled trials), or research that requires a representative sample (e.g. population-based surveys) is warranted.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were generated or analysed during this study.

References

2 Australian Communications and Media Authority. Communications and media in Australia: how we communicate. Commonwealth of Australia; 2023. Available at https://www.acma.gov.au/publications/2023-12/report/communications-and-media-australia-how-we-communicate

3 Sanchez C, Grzenda A, Varias A, Widge AS, Carpenter LL, McDonald WM, et al. Social media recruitment for mental health research: a systematic review. Compr Psychiatry 2020; 103: 152197.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

4 Whitaker C, Stevelink S, Fear N. The use of facebook in recruiting participants for health research purposes: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2017; 19(8): e290.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

5 Harfield S, Elliott S, Ramsey L, Housen T, Ward J. Using social networking sites to recruit participants: methods of an online survey of sexual health, knowledge and behaviour of young South Australians. Aust N Z J Public Health 2021; 45(4): 348-54.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

6 Gunasekaran B, Jayasinghe Y, Fenner Y, Moore EE, Wark JD, Fletcher A, et al. Knowledge of human papillomavirus and cervical cancer among young women recruited using a social networking site. Sex Transm Infect 2013; 89(4): 327-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

7 Coombe J, Kong F, Bittleston H, Williams H, Tomnay J, Vaisey A, et al. Contraceptive use and pregnancy plans among women of reproductive age during the first Australian COVID-19 lockdown: findings from an online survey. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2021; 26(4): 265-71.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

8 Coombe J, Kong FYS, Bittleston H, Williams H, Tomnay J, Vaisey A, et al. Love during lockdown: findings from an online survey examining the impact of COVID-19 on the sexual health of people living in Australia. Sex Transm Infect 2021; 97(5): 357-62.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

9 Bittleston H, Goller JL, Temple-Smith M, Hocking JS, Coombe J. Telehealth for sexual and reproductive health issues: a qualitative study of experiences of accessing care during COVID-19. Sex Health 2022; 19(5): 473-78.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

10 Bourchier L, Bittleston H, Hocking J, Coombe J. Changes to pubic hair removal practices during COVID-19 restrictions and impact on sexual intimacy. Cult Health Sex 2023; 25(4): 505-20.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

11 Coombe J, Bittleston H, Hocking JS. Access to period products during the first nation-wide lockdown in Australia: results from an online survey. Women Health 2022; 62(4): 287-92.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

12 Goller JL, Bittleston H, Kong FYS, Bourchier L, Williams H, Malta S, et al. Sexual behaviour during COVID-19: a repeated cross-sectional survey in Victoria, Australia. Sex Health 2022; 19(2): 92-100.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

13 Fang W, Coombe J, Hocking JS, Bittleston H. Are COVID-19 lockdowns associated with a change in sexual desire? Results from an online survey of Australian women. Women Health 2023; 63(7): 531-38.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

14 Stewart LL, Vodstrcil LA, Coombe J, Bradshaw CS, Hocking JS. Bacterial vaginosis after menopause: factors associated and women’s experiences: a cross-sectional study of Australian postmenopausal women. Sex Health 2024; 21: SH23094.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

15 Eddy S, Douglass C, Raggatt M, Thomas A, Lim M. Trends in testing of sexually transmissible infections (STIs), sexual health knowledge and behaviours, and pornography use in cross-sectional samples of young people in Victoria, Australia, 2015–21. Sex Health 2023; 20(2): 164-72.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

16 Munari SC, Goller JL, Coombe J, Orozco A, Eddy S, Hocking J, et al. Young people’s preferences and motivations for STI partner notification: observational findings from the 2024 sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll survey. Sex Health 2025; 22: SH24184.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

17 Ramsay C, Hennegan J, Douglass CH, Eddy S, Head A, Lim MSC. Reusable period products: use and perceptions among young people in Victoria, Australia. BMC Womens Health 2023; 23(1): 102.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

18 Lim MSC, Kirsten R, Davis AC, Wright CJC. ‘Censorship is cancer’. Young people’s support for pornography-related initiatives. Sex Educ 2021; 21(6): 660-73.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

19 Douglass CH, Qin C, Martin F, Xiao Y, El-Hayek C, Lim MSC. Comparing sexual behaviours and knowledge between domestic students and Chinese international students in Australia: findings from two cross-sectional studies. Int J STD AIDS 2020; 31(8): 781-90.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

20 Davis AC, Temple-Smith MJ, Carrotte E, Hellard ME, Lim MSC. A descriptive analysis of young women’s pornography use: a tale of exploration and harm. Sex Health 2020; 17(1): 69-76.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

21 Bourchier L, Temple-Smith M, Hocking J, Bittleston H, Malta S. Engaging older Australians in sexual health research: SHAPE2 survey recruitment and sample. Sex Health 2024; 21(1): SH23116.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

22 Bourchier L, Temple-Smith M, Hocking JS, Malta S. Older patients want to talk about sexual health in Australian primary care. Aust J Prim Health 2024; 30(4): PY24016.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

23 Bittleston H, Goller JL, Temple-Smith M, Coombe J, Hocking JS. How much do young australians know about syphilis compared with chlamydia and gonorrhea? Findings from an online survey. Sex Transm Dis 2023; 50(9): 575-82.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

24 Bittleston H, Hocking JS, Coombe J, Temple-Smith M, Goller JL. Young Australians’ receptiveness to discussing sexual health with a general practitioner. Aust J Prim Health 2023; 29(6): 587-95.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

25 Bittleston H, Hocking JS, Temple-Smith M, Sanci L, Goller JL, Coombe J. What sexual and reproductive health issues do young people want to discuss with a doctor, and why haven’t they done so? Findings from an online survey. Sex Reprod Healthc 2024; 40: 100966.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

26 Ludwick T, Walsh O, Cardwell ET, Chang S, Kong FYS, Hocking JS. Moving toward online-based sexually transmitted infection testing and treatment services for young people: who will use it and what do they want? Sex Transm Dis 2024; 51(3): 220-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

27 Walsh O, Cardwell ET, Hocking JS, Kong FYS, Ludwick T. Where would young people using an online STI testing service want to be treated? A survey of young Australians. Sex Health 2024; 21: SH24087.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

28 Cardwell ET, Walsh O, Chang S, Coombe J, Fairley CK, Hocking JS, et al. Preferences for online or in-person STI testing vary by where a person lives and their cultural background: a survey of young Australians. Sex Transm Infect 2025; 101(3): 168-73.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

29 Cardwell ET, Ludwick T, Chang S, Walsh O, Lim M, Podbury R, et al. Engaging end users to inform the design and social marketing strategy for a web-based sexually transmitted infection/blood-borne virus (STI/BBV) testing service for young people in Victoria, Australia: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res 2025; 27: e63822.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

31 Orozco A, Thomas A, Raggatt M, Scott N, Eddy S, Douglass C, et al. Coping with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study on young Australians’ anxiety and depression symptoms from 2020–2021. Arch Public Health 2024; 82(1): 166.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

32 Witkovic YD, Kim HC, Bright DJ, Tan JY. Recruiting black men who have sex with men (MSM) couples via dating apps: pilot study on challenges and successes. JMIR Form Res 2022; 6(4): e31901.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |