Personal experiences of appropriate access to post-acute care services in acquired brain injury: a scoping review

Kirstyn Laurie A B * , Michele Foster

A B * , Michele Foster  A B and Louise Gustafsson

A B and Louise Gustafsson  A B

A B

A The Hopkins Centre: Research for Rehabilitation and Resilience,

B School of Health Sciences and Social Work,

Abstract

People with an acquired brain injury (ABI) experience substantial access inequalities and unmet health needs, with many experiencing insufficient access to appropriate rehabilitation in the community. To deepen our understanding of what appropriate access to post-acute care services is for this population, and to facilitate optimal recovery, there is a need to synthesise research from the service user perspective. A scoping review study was conducted to identify key characteristics of ‘appropriate’ access to post-acute care services, as defined by the personal experiences of adults with ABI. Electronic scientific databases Medline, PsycINFO, Proquest Central and CINAHL were searched for studies published between 2000 and 2020. The initial search identified 361 articles which, along with articles retrieved from reference list searches, resulted in 52 articles included in the final analysis. Results indicated that a majority of the studies sampled participants with an average of over 1 year post-injury, with some studies sampling participants ranging over 10 years in difference in time post-injury. A thematic synthesis was conducted and results indicated a number of dominant elements which relate to (1) the characteristics of services: provider expertise, interpersonal qualities, partnership and adaptability; (2) characteristics of the health system: navigable system, integrated care, adequacy, and opportunity. These findings provide some insight into what might be considered appropriate. However, rigorous research, focused on personalised access to post-acute care services, is recommended to verify and elaborate on these findings.

Keywords: Access, adequacy, rehabilitation, post-acute, lived experience.

Introduction

Acquired brain injury (ABI) is one of the leading causes of disability, with global prevalence rates predicted to be one in 500 people (Bryan-Hancock & Harrison, 2010; Roozenbeek, Maas & Menon, 2013). This encompasses brain injury occurring after birth and includes traumatic injuries (TBI) as a result of external force and injuries acquired through nontraumatic processes, such as a stroke (O’Rance & Fortune, 2007). An ABI can result in temporary and long-term disturbances in mood and behaviour and deficits in cognitive, physical and psychosocial functioning (Fleminger & Ponsford, 2005; Kumar, Kumar & Singh, 2019). Consequently, treatment involves a complex, and preferably individualised, mix of acute and post-acute health and rehabilitation services and health professionals (de Koning, Spikman, Cores, Schönherr & van der Naalt, 2015; Jolliffe, Lannin, Cadilhac & Hoffmann, 2018; Mellick, Gerhart & Whiteneck, 2003; Prang, Ruseckaite & Collie, 2012).

Specialist rehabilitation pathways have emerged to address the complex needs of individuals with ABI. These pathways provide a comprehensive mix of rehabilitation services to support the individual in their recovery from acute to post-acute care (Turner-Stokes, Pick, Nair, Disler & Wade, 2015). Whilst lacking a definitive consensus, Buntin (2007) defines post-acute care as services focusing on patients’ needs after leaving acute in-hospital care. The post-acute phase can include structured programmes such as transitional living programmes, outpatient day therapy and community integration programmes, in addition to disciplinary-specific neurobehavioural services (Hall, Grohn, Nalder, Worrall & Fleming, 2012; Simpson et al., 2004). Ongoing access to post-acute care services after discharge, which includes post-acute primary health care and rehabilitation services, is imperative to the maintenance and continuation of recovery (Jolliffe et al., 2018; Turner-Stokes et al., 2015; Turner et al., 2011a). However, studies have indicated that access often reduces across the transition from inpatient care back to the community (Abrahamson, Jensen, Springett & Sakel, 2017; O’Callaghan, McAllister & Wilson, 2010). Of concern, a significant proportion of people who acquire a brain injury have insufficient access to adequate post-acute care services in the community in the first year, or miss out altogether (Collie & Prang, 2013; Foster et al., 2015; Foster, Fleming, Tilse & Rosenman, 2000; Mellick et al., 2003; Ta’eed, Skilbeck & Slatyer, 2013).

To facilitate the optimal gains in recovery, treatment and care appropriate to each individual is essential (Conneeley, 2012; Hall et al., 2012). Yet, planning and achieving appropriateness across the continuum is challenging (Copley, McAllister & Wilson, 2013; Turner-Stokes et al., 2015). Further, the concept of appropriate access is ill defined when it comes to people who acquire a brain injury. Whilst lacking a consensus, appropriateness of access concerns the fit of the service to the user needs, centring around issues of timeliness, quality of care, adequacy and continuity of care (Levesque, Harris & Russell, 2013). One component of appropriateness, adequacy of services, has been defined as how well the services received meets patients’ needs. This is if there is sufficiency of services, if there are quality services, and whether what is provided is good enough (Levesque et al., 2013; Morrow-Howell, Proctor & Dore, 1998). The necessity for appropriate access to post-acute care services is emphasised through the guidelines promoting specialist pathways and early and ongoing rehabilitation for people with ABI (Turner-Stokes et al., 2015). In Australia, the specialist rehabilitation pathways differ across states and territories, and with regard to the private and public funding pathways (Muenchberger, Kendall & Collings, 2001).

Although the benefits of appropriate access underpin standards in early and long-term recovery, access needs are highly personal. This aligns with the paradigm shift in how services are provided to people with lifelong disabling conditions, taking account of the aspirations and preferences of the service user, to ensure services are matched appropriately to their needs (Foster et al., 2016). This is evidenced through the implementation of major policy reforms, such as the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) in Australia. The NDIS was introduced to address equity in access to services for people with disability, through the implementation individualised funding to citizens with permanent and significant disability (Productivity Commission, 2011). However, as illustrated through ongoing disparities and unmet needs of people with ABI, these services may not always fit with service users’ perceived needs or expectations (Copley et al., 2013; Foster et al., 2015). Therefore, there is a need to conceptualise appropriate access to post-acute care services in people with ABI. This can provide new insights about how we match services to need.

There has been an increase in research focusing on the user perspective of service access, with a growing interest in the personal experiences and recovery trajectories of those who have ABI. Research addressing personal experiences of access to rehabilitation and support services indicates what might be important to people with brain injury when defining appropriateness. A review of the literature in both giving and receiving care across the TBI trajectory, pointed to key components of appropriateness when it comes to access to services (Kivunja, River & Gullick, 2018). Themes related to how people with TBI received care were clustered into two main categories. The first, challenges to self-identity, included experiencing insensitivity of health professionals, wanting to overcome authoritative rule and having input into personal care. The second, feeling different, which included lacking control, being excluded from care planning, needing practical help, including longing for the right kind of help, and inadequacy of organisational resources. Further, Jackson, Hamilton, Jones and Barr (2019) conducted a systematic review of patient reported experiences of community rehabilitation and support services of people with long-term neurological conditions. Analysis of 37 articles concluded that process quality, activities associated with person-centred care and interactions with health professionals’ impact on service engagement and are seen as important.

These reviews provide insight into what valued characteristics are emerging from the literature when it comes to understanding personal experiences of receiving community rehabilitation and support. However, Kivunja et al. (2018) reviewed articles pertaining to those with traumatic brain injury which constrains conclusions that can be drawn about the literature in acquired brain injury more broadly. Additionally, the review included all services including inpatient hospital service access. The literature suggests that access experiences vary across the individual’s trajectory, for example that information needs are often met during hospital stay and these emerge after discharge back into the community (Hall et al., 2012; Rusconi & Turner-Stokes, 2003). Jackson et al. (2019) focused on community rehabilitation access however limited the search to qualitative work. Additionally, the focus of this review included progressive neurological conditions, such as multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease. Whilst some comparisons were drawn, access needs and pathways differ significantly for those with these conditions, therefore synthesis of the personal experiences of those with ABI separately would increase the generalisability of the findings.

To deepen our understanding of what appropriate access to post-acute care services is for this population, there is a need to synthesise the literature on post-acute access to services in people with an ABI. Therefore, the aim of this scoping review was to identify key characteristics of ‘appropriate’ access, as defined by the personal experiences of people with ABI, and to identify knowledge gaps in this literature. The review aimed to answer the research question: what do personal experiences of post-acute care service access indicate about characteristics of appropriateness of access for adults with an ABI?

Method

Design

A scoping review was conducted to examine the literature related to the appropriate access to post-acute care services, defined by the personal experiences of people with an ABI. While systematic reviews typically focus on a well-defined research question, seeking to assess the quality of evidence, scoping reviews are an alternative method of reviewing evidence (Grant & Booth, 2009). Scoping reviews are commonly used to synthesise the literature on broad topics, identify key concepts and gaps in the literature (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Halas et al., 2015). The present study utilises the 5-stage methodological framework developed by Arksey & O’Malley (2005) which consists of the following stages: 1. Develop the research question; 2. Search for relevant literature; 3. Select the literature/studies; 4. Chart the data: and 5. Collate, summarise and report the results.

Identifying the research question

The present scoping review aimed to answer the following research question: What do personal experiences of post-acute care service access indicate about characteristics of appropriateness of access for adults with an ABI?

Identifying relevant studies

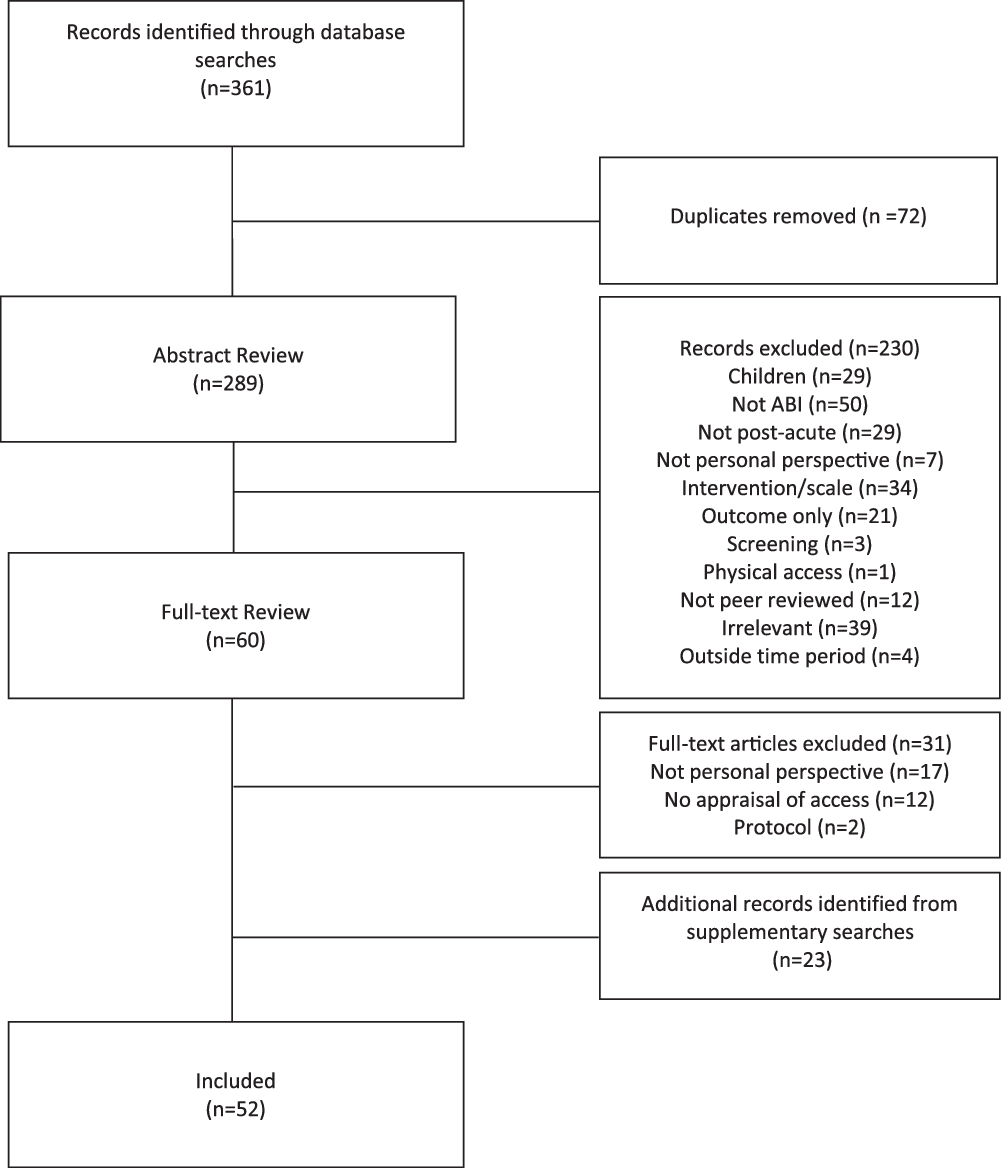

Electronic scientific databases were utilised for the review, see Table 1. A list of terms and filtering options for the search were developed by the research team (Author A, Author B, Author C) based on initial orientation searches, which resulted in search outcomes that were tailored to the research question. In addition, reference lists were checked to identify other relevant articles to obtain a comprehensive set of literature on this topic. The initial search produced 361 articles. After duplicate articles were removed (n = 72) there were 289 articles. The initial search strategy was developed and refined using an iterative process by the research team (Author A, Author B, Author C), with all members reviewing search results at each phase.

Table of Search Criteria

| Search terms | Concept 1: Appropriateness | Concept 2: ABI | Concept 3: Healthcare | Concept 4: Access | |

| adequa* OR satisfact* OR quality OR “patient attitude” OR “patient perspective” OR “consumer participation” OR appropriate OR sufficien* OR acceptab* OR inadequa* OR inappropriate OR insufficien* OR unacceptab* OR dissatisfaction | “acquired brain damage” OR “brain injury” | rehabilitation OR “health services” OR “community services” OR healthcare | access* | ||

| Databases | Medline, PsycINFO, Proquest Central and CINAHL | ||||

| Inclusion | Published in the last 20 years (2000–2020); published in academic, peer-reviewed journals; Written in English; Appraising human subjects only; In adults (18 and older); From the personal perspectivesa ; Comprising of people diagnosed with an ABI; Concerning access experiences after discharge from inpatient rehabilitationb | ||||

| Exclusion | Degenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease or some other form of dementia; Congenital brain impairment; Solely concerning physical access; More than half the sample under 18 years old; Caregivers interviewed on behalf of participant only; Less than a third of the sample has an ABI; Solely describing service use, outcomes or needs, without appraisal of access; Appraisal of specific intervention or scale only | ||||

Study selection

In the study selection phase, the relevance of the literature was assessed at abstract and full-text level. The first author (A) conducted the database searches and exported the results into Endnote bibliographic software. Abstracts were then reviewed for relevancy based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed by all members of the research team (Author A, Author B, Author C). See Table 1 for detail pertaining to the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the articles. Exemplar articles based on these criteria, and articles which were difficult to determine eligibility, were reviewed and discussed as a group to obtain consensus. Full texts of the remaining publications were reviewed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, along with articles found in references list checks, leaving articles for data extraction and charting.

Charting the data, collate, summarise and report the results

A data extraction template was developed based on a small subset of full texts and research team consultation (Author A, Author B, Author C) including the following: authors; year and country of publication; aim(s) of study; study design; study participants (number of ABI participants); time since injury/discharge; type of service if specified; access characteristics that were valued by participants; access characterises that were problematic for participants. The 52 selected articles were then reviewed and data extracted by Author A based on this template. A thematic synthesis was conducted (Thomas & Harden, 2008) which included three phases. Results of each included paper were reviewed and findings relating to the personal access experience post-discharge from inpatient rehab were extracted (Author A). Once text segments were extracted, results were categorised into what was valued (appreciated, satisfactory, positive) as part of their access experience and what was problematic. These were then organised into key descriptive themes using Levesque et al. (2013) conceptualisation of appropriate access as benchmark for comparison against review findings; however, results were not constrained to fit. In the final stage, the results were then analysed and ‘analytical themes’ emerge. Emerging themes and findings were collated and reviewed and validated by members of the research team (Author A, Author B, Author C) through an iterative process. Once themes were finalised the articles were reviewed again, and finalised themes were then assigned to each article. Results of the review are presented below.

Results

Descriptive summary of the articles

There was a total of 52 studies that were included in the scoping review. See Fig. 1 for the flow diagram of included studies. The majority of articles were published between 2010 and 2020 (n = 39/52). The articles included thirty-six qualitative, seven quantitative, six mixed methods studies, and three reviews. The studies were conducted in Australia (n = 16), the USA (n = 13), the United Kingdom (n = 5), Canada (n = 5), Sweden (n = 3), New Zealand (n = 2), Denmark (n = 2) and one each in France, Ireland, South Africa and Botswana.

Twenty-six of the articles included both people with a brain injury and family members/caregivers in their samples, and participant numbers ranged from two to 1830 participants. Participants in the studies were either within a year post-discharge (n = 4), more than 1-year post-injury (n = 26), included both (n = 7) or did not report specific time since discharge or injury (n = 12). Twenty-nine of the articles were focused on TBI exclusively, twenty-one included those with ABI, one was all non-TBI brain injuries, and one was stroke specific. Few of the articles were focused on specific populations including war veterans (n = 3), women (n = 1), those in rural and remote locations (n = 3), culturally diverse or indigenous populations (n = 3), and those with alcohol-related injury (n = 1). Thirteen of the articles were regarding a specific service, including occupational therapy (n = 2), vocational or return to work (n = 4), group rehabilitation (n = 1), respite (n = 1), residential settings (n = 2) and aged care settings (n = 2), and specific funding (n = 1).

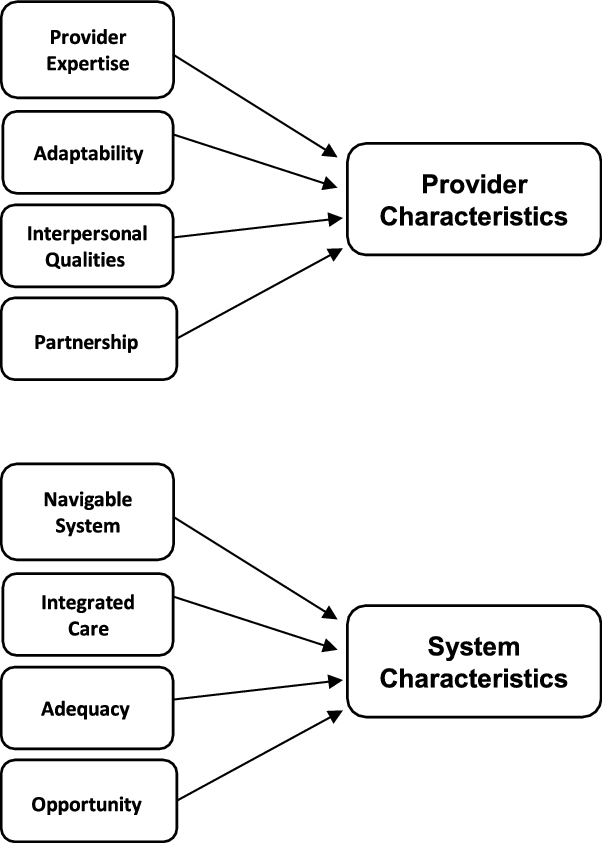

Findings

The review aimed to answer the research question: what do personal experiences of post-acute care service access indicate about characteristics of appropriateness of access for adults with an ABI? The synthesis identified eight thematic ideas which were then grouped under two broader themes. See Fig. 2. The first of these was characteristics of the provider: (i) provider expertise (n = 26); (ii) interpersonal qualities (n = 18); (iii) partnership (n = 21); (iv) adaptability (n = 14). The second was the characteristics of the service system: (v) navigable system (n = 24); (vi) integrated care (n = 33); (vii) adequacy (n = 25); and (viii) opportunity (n = 23). The access characteristics of each publication are presented in Table 2.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Author (year); country | Study methodology | Sample; time since injury/discharge; method of data collection | Specific service/sample (if applicable) | Study aim | Access characteristics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chamberlain (2006); Australia | Mixed methods | N = 20; Within 1-year post-injury; Unstructured in-depth interviews and interview survey questionnaires including standardised measures and nonstandard/adapted questions | TBI | To describe the experience of surviving TBI as narrated by patients 1 year after injury | Interpersonal qualities, integrated care | |

| Copley et al. (2013); Australia | Mixed methods | N = 202; Qualitative = 23 (14 with TBI Proxy = 9); NR; Unstructured in-depth interviews and written survey questionnaire including nonstandard/adapted questions | Moderate or Severe TBI | To explore the recollected continuum of care experienced by adults with moderate to severe TBI | Provider expertise, adequacy, integrated care, partnership | |

| Glintborg et al. (2018); Denmark | Mixed methods | N = 37; 2 years post-discharge; Semi-structured in-depth interviews and written survey questionnaire including standardised measures | Moderate or Severe ABI | To investigate the status of clients with moderate or severe ABI on physical and cognitive function, depression, quality of life, civil and work status and explore through qualitative interviews the subjective experiences of these individuals | Partnership, adequacy | |

| Hall et al. (2012); Australia | Mixed methods | N = 6; At discharge and 6 months post-discharge; Semi-structured in-depth interviews and written survey questionnaire including standardised measures and nonstandard/adapted questions | Non-TBI | The purpose of this study was to explore the transition experiences of individuals with nontraumatic BI using mixed methods approach | Adaptability, integrated care, navigable system | |

| Snell et al. (2017); New Zealand | Mixed methods | N = 10; 6–52 months post-injury; Semi-structured in-depth interviews and written survey questionnaire including standardised measures and nonstandard/adapted questions | Mild TBI | To explore the symptoms, recovery and treatment experiences of a sample of recovered and non-recovered MTBI participants | Interpersonal qualities, provider expertise, partnership | |

| Umeasiegbu et al. (2013); USA | Mixed methods | N = 100; Qualitative = 22 (19 Proxy); Within 10 years post-injury for 66% of sample; Semi-structured focus group interviews and written survey questionnaire including standardised measures and nonstandard/adapted questions | Outpatient service users; ABI | To identify the rehabilitation services needs, the rehabilitation goals, and the barriers that persons with ABI and their families encounter as they navigate the recovery process | Integrated care, opportunity, navigable system, adequacy, partnership | |

| Qualitative | ||||||

| Abrahamson et al. (2017); United Kingdom | Qualitative | N = 10 (and 9 S/Os); 1 month post-discharge; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Transition from hospital home; Severe TBI | To explore the experiences of individuals who have had a severe TBI and their carers in the first-month post-discharge from in-patient rehabilitation into living in the community | Partnership, integrated care, adequacy, provider expertise | |

| Braaf et al. (2019); Australia | Qualitative (embedded) | N = 6 (and 12 family members of people with TBI); 4 years post-injury; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Severe TBI | To explore experiences of care coordination in the first 4 years after severe TBI | Interpersonal qualities, integrated care, provider expertise, adequacy, opportunity | |

| Brauer et al. (2011); USA | Qualitative | N = 5 (Proxy); NR; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Occupational therapy; Severe TBI | The purpose of this qualitative study is to gain insight into the continuum of occupational therapy services provided for individuals with TBI and to gather inputs from such individuals’ caregivers regarding their perspectives on the lived experience of TBI in relation to received occupational therapy services | Integrated care, adequacy, provider expertise, adaptability | |

| Conneeley (2012); United Kingdom | Qualitative | N = 18 (and 18 S/O and 14 health professionals); Over 1 year post-discharge; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | ABI | The aim of this article is to contribute to this body of knowledge by presenting findings of a qualitative study that explored the views of the individual with brain injury, their family member and the rehabilitation team involved in their care, over a period of 1 year following discharge from a neurological rehabilitation ward | Partnership, integrated care | |

| Dams-O'Connor et al. (2018); USA | Qualitative | N = 44; 13 years post-injury on average ; Semi-structured in-depth focus groups | ABI | To gather information about BI survivors’ long-term healthcare needs, quality, barriers and facilitators | Provider expertise, interpersonal qualities, integrated care, adaptability, navigable system, opportunity, adequacy | |

| Doig et al. (2011); Australia | Qualitative | N = 12 (and 12 S/O and 3 OTs); NR; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Occupational therapy; TBI | To explore how therapy in a home and day hospital setting impacts on rehabilitation processes and outcomes from the perspective of the patients, their significant others and their treating occupational therapists | Adaptability, partnership | |

| Dwyer et al. (2019); Ireland | Qualitative | N = 6; NR; Semi-structured in-depth interview | Aged care facilities; ABI | This study explored the lived experiences of young adults with ABI residing in aged care facilities | Opportunity, interpersonal qualities | |

| Eliacin et al. (2018); USA | Qualitative | N = 34 ( and 28 S/O); 0–4 years = 14, 5–10 years = 12, 10+ years post-injury = 7; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | TBI | The objective was to provide an understanding of their lived experiences and to inform policies and practices for health services delivery for TBI | Provider expertise, opportunity | |

| Gill et al. (2012); United Kingdom | Qualitative | N = 7; 0–5 years = 4, 5–9 years = 1, 10–14 years = 1, 20–25 years = 1 post-injury; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Community residential rehabilitation; ABI | To examine clients’ perspectives on residential rehabilitation for ABI | Partnership, interpersonal qualities, adequacy | |

| Graff et al. (2018); Denmark | Qualitative | N = 20; 1–4 years post-injury: Mild TBI at 1–2 years, moderate at 2–3 years and severe at 3–4 years post-injury; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | TBI | This study aimed to provide an understanding of the lived experience of rehabilitation in adults with TBI from hospital discharge up to 4 years post-injury | Navigable system, integrated care, opportunity | |

| Harrington et al. (2015); Australia | Qualitative | N = 10 (and 17 S/O); 8 months to 19 years post-injury, M = 7.9 years; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Funding Pathways; TBI | To explore experiences of pathways, outcomes and choice after motor vehicle accident acquired severe TBI under fault-based vs no-fault motor accident insurance | Opportunity, navigable system, integrated care, adequacy | |

| Harrison et al. 2017; USA | Qualitative | N = 13 (and 6 S/O); 1–9 years post-injury, M = 5.8 years; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Rural community; TBI | The purposes of this study were to (1) increase understanding of the lived experience of people with TBI and caregivers in rural regions of Kentucky across the continuum of their care and (2) provide their perspectives on barriers and facilitators of optimal function and well-being | Provider expertise, opportunity, integrated care | |

| Hooson et al. 2013; United Kingdom | Qualitative | N = 10; 3–9 years post-injury, M = 5.5 years; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Return to Work Rehabilitation (RTW); Medium-severe TBI | To understand positive contributors to work (RTW) rehabilitation for people with multiple TBI impairments and disabilities | Provider expertise, partnership, interpersonal qualities, integrated care | |

| Hyatt et al. 2014; USA | Qualitative | N = 9 (and 9 S/Os); 6–18 months post-injury, M = 12 months; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | War Veterans; Mild TBI | This research describes the rehabilitation experiences of soldiers with a history of mild TBI and their spouses | Navigable system, provider expertise, partnership, integrated care, interpersonal qualities, adequacy | |

| Jumisko et al. 2007; USA | Qualitative | N = 12 (and 8 S/O); NR; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Moderate or Severe TBI | To describe how people with moderate or severe TBI and their close relatives are treated/perceived by others in their world | Navigable system, interpersonal qualities, partnership, adaptability, provider expertise | |

| Keightley et al. 2011; Canada | Qualitative | N = 3 (and 3 S/O and 11 hospital and community service workers); NR; Semi-structured in-depth focus groups | Aboriginal Community; ABI | To explore the barriers and enablers surrounding the transition from health care to home community settings for Aboriginal clients recovering from acquired brain injuries (ABI) in northwestern Ontario | Opportunity, provider expertise | |

| Lefebvre and Levert (2012); Canada and France | Qualitative | N = 56 (and 34 S/O and 60 healthcare professionals); 2–7 years post-injury, M = 4.3 years; Semi-structured in-depth focus groups | TBI | To explore the needs of individuals with TBIs and their loved ones throughout the continuum of care and services | Interpersonal qualities, provider expertise, adequacy, integrated care, partnership, navigable system | |

| Lefebvre et al. 2005; Canada | Qualitative | N = 8 (and 14 S/Os and 31 healthcare professionals); 2–6 years post-injury, M = 2.8 years; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | TBI | To investigate the experience of individuals who had sustained a TBI, their families and the physicians and health professionals involved, from critical care episodes and subsequent rehabilitation | Interpersonal qualities, navigable system, partnership, opportunity, adequacy, integrated care | |

| Leith et al. 2004; USA | Qualitative | N = 10 (and 11 S/Os); 1–5 years post-injury; Semi-structured in-depth focus groups | TBI | The objective was to learn what participants perceive their service needs to be and where they experience service gaps in the existing system of TBI services | Provider expertise, adaptability, partnership, opportunity, navigable system, adequacy | |

| Lexell et al. 2013; Sweden | Qualitative | N = 11; 4–14 years post-injury, M = 6.4 years; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Outpatient Group Rehabilitation; ABI | The aim of this study was to describe how persons with ABI experience an out-patient group rehabilitation programme and how the programme had contributed to their everyday lives | Provider expertise, adequacy | |

| Maratos et al. (2016); Canada | Qualitative | N = 5; 3–10 years post-injury; Photovoice and focus groups | Stroke | The aim of this study was to explore the lived experience of high-functioning stroke survivors and to identify gaps in community and rehabilitation services | Partnership; opportunity | |

| Martin et al. (2015); New Zealand | Qualitative | N = 5; 1.3–36 years post-injury; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Residential facility; Severe ABI | The objective of this study was to explore the lived experience and perceptions of life goals from the perspective of those with severe ABI, living in a long-term residential rehabilitation setting | Partnership, interpersonal qualities, opportunity | |

| Matérne et al. (2017); Sweden | Qualitative | N = 10, 3–9 years post-injury; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | RTW; ABI | The aim was to increase knowledge of opportunities and barriers for a successful RTW in patients with ABI | Partnership | |

| Mbakile-Mahlanza et al. (2015); Botswana | Qualitative | N = 21 (and 18 S/Os and 25 health professionals); 6 months to 1 year = 9, 1–3 years = 6, 3 years and over post-injury = 7; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Moderate to severe TBI | This study aimed to explore the experiences of TBI in Botswana | Navigable system, provider expertise, opportunity, adequacy, interpersonal qualities, integrated care | |

| Mitsch et al. (2014); Australia | Qualitative | N = 6 (and 7 S/Os and 59 service providers); Over 3 years post-injury; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Rural and Remote; ABI | The objectives of this research were to investigate the equity of BI rehabilitation services to rural and remote areas of the state of New South Wales, Australia and to describe the experience of people who access and who deliver these services | Provider expertise, opportunity, adaptability, adequacy, integrated care | |

| O'Callaghan et al. (2012a); Australia | Qualitative | N = 3; NR; Unstructured in-depth interviews | Moderate to severe ABI | The aim of this article is to convey how the needs and experiences of adults with BI change throughout time, affecting their ability to access care over time | Interpersonal qualities, provider expertise, integrated care, adequacy | |

| O'Callaghan et al. (2012b); Australia | Qualitative | N = 14 (and 9 S/Os); NR; Unstructured in-depth interviews | Moderate to severe TBI | This study aimed to look beyond the development of self-awareness and insight in order to explore the concept of readiness as it relates to clients’ experiences of engaging with therapy | Adaptability, navigable system, integrated care, adequacy | |

| Rotondi et al. (2007); USA | Qualitative | N = 80 (and 85 S/Os); M = 5.8 years post-injury; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | TBI | To determine the expressed needs of persons with TBI and their primary family caregivers | Integrated care, adaptability, adequacy, navigable system, provider expertise | |

| Simpson et al. (2000); Australia | Qualitative | N = 18 (and 21 S/Os); 5 months to 11 years post-injury, M = 3.5 years; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Cultural Variations (Italian, Lebanese and Vietnamese backgrounds) TBI | To research cultural variations in the understanding of BI, its effects, and the rehabilitation process amongst people from Italian, Lebanese and Vietnamese backgrounds in the South Western Sydney Region | Interpersonal qualities, integrated care, opportunity | |

| Soeker et al. (2012); South Africa | Qualitative | N = 10; Over 1 year post-injury; Unstructured in-depth interviews | RTW Rehab; Mild or Moderate BI | To describe the perceptions and experiences of individuals with BI with regard to return to work rehabilitation programmes | Interpersonal qualities, navigable system, partnership | |

| Strandberg (2009); Sweden | Qualitative | N = 15; 5 months to 17 years post-injury; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | TBI | The purpose of this study is to illuminate the changeover process, support, and consequences experienced by adults who acquired a TBI | Integrated care, provider expertise, partnership | |

| Turner et al. (2007); Australia | Qualitative | N = 13 (and 11 S/O); 2 months to 4.4 years post-injury, M = 15.2 months; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Transition from hospital home; ABI | To explore the transition experiences from hospital to home of a purposive sample of individuals with ABI | Integrated care, navigable system, adequacy, opportunity, provider expertise | |

| Turner et al. (2011a); Australia | Qualitative | N = 20 (and 18 S/Os); prior to discharge from hospital, 1 and 3 months post-discharge; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Transition from hospital home; ABI | To explore the service and support needs of individuals with ABI and their family caregivers during the transition phase from hospital to home | Integrated care, adequacy, adaptability, navigable system | |

| Turner et al. (2011b); Australia | Qualitative | N = 20 (and 18 S/Os); prior to discharge from hospital, 1 and 3 months post-discharge; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Transition from hospital home; ABI | To explore the perspectives of individuals with ABI and their family caregivers concerning recovery and adjustment during the early transition phase from hospital to home | Adaptability | |

| Winkler et al. (2011); Australia | Qualitative | N = 7 (and 7 S/Os and 2 support workers); 2–15 years post-injury, M = 8.1 years; Semi-structured in-depth interviews | Aged care facility; ABI | To understand the outcomes of the transition experiences of young people with ABI in Australia who have lived in aged care facilities and subsequently moved into the community as well as the perspectives of their significant carers/carers | Adequacy, provider expertise, opportunity, integrated care, partnership | |

| Wyse et al. (2020); USA | Qualitative | N = 37; NR; Semi-structured in-depth interviews and focus groups | Return to Work, Employment and Vocational Rehabilitation; War Veterans; TBI | This study utilised qualitative interviews and focus groups with veterans with documented polytrauma/TBI history to explore veterans’ perceived barriers to employment and vocational rehabilitation programme participation, as well as to solicit thoughts regarding interest in an evidence-based vocational rehabilitation programme, the Individual Placement and Support Model of Supported Employment | Provider expertise, adequacy, opportunity, adaptability, navigable system | |

| Quantitative | ||||||

| Chan (2008); Australia | Quantitative | N = 62; 1–50 years post-injury, Median = 14 years; Written survey questionnaire including nonstandard/adapted questions | Respite Services; ABI | The study aimed to identify the characteristics of persons with ABI who were using or not using respite, to explore the factors influencing respite use and to determine expectations of respite and need for other support services | Provider expertise, adaptability, navigable system, integrated care | |

| O'Callaghan et al. (2010); Australia | Quantitative | N = 202; 2–7 years post admission; Written survey questionnaire including nonstandard/adapted questions | Moderate to Severe TBI | This paper investigates the continuum of care experienced by adults and their significant others following a moderate to severe TBI in Victoria, Australia | Integrated care, opportunity | |

| Pickelsimer et al. (2007); USA | Quantitative | N = 1830; 1 year post-discharge; Telephone survey questionnaire including standardised measures and nonstandard/adapted questions | TBI | To assess unmet needs of persons with TBI 1 year after hospital discharge; compare perceived need with needs based on deficits (unrecognised need); determine major barriers to services; evaluate association of needs with satisfaction with life | Adaptability, navigable system, integrated care, opportunity | |

| Rusconi and Turner-Stokes (2003); United Kingdom | Quantitative | N = 22 (and 31 proxy); 8 – 21 months post-discharge, M = 14.9; Telephone survey questionnaire including standardised measures and nonstandard/adapted questions | ABI | To evaluate the aftercare of patients discharged from a specialist rehabilitation unit with respect to use of equipment and follow-up by therapy and care services and to assess change in dependency and care needs | Provider expertise, adequacy, navigable system, integrated care | |

| Schulz-Heik et al. (2017); USA | Quantitative | N = 119; 5–16 years post-injury, Median = 8; Telephone survey questionnaire including standardised measures and nonstandard/adapted questions | War veterans; Moderate to severe TBI | The objective of this paper is to identify the most frequent service needs, factors associated with needs, and barriers to care among Veterans and service members 5 or more years after moderate to severe TBI | Navigable system | |

| Solovieva and Walls (2014); USA | Quantitative | N = 722; NR; Written survey questionnaire including nonstandard/adapted questions | Rural setting; TBI | To summarise results from survey results from consumers of a TBI registry | Navigable system, provider expertise, interpersonal qualities | |

| Toor et al. (2016); Canada | Quantitative | M = 105 (and 105 without TBI); 5–12 years post-injury, M = 7.7 years; Telephone survey questionnaire including standardised measures and nonstandard/adapted questions | Women; TBI | To assess long-term health care service utilisation and satisfaction with health care services among women with TBI, examine barriers that prevent them from receiving care when needed and understand the perceived supports available | Opportunity | |

| Reviews | ||||||

| Brighton et al. (2013); N/A | Review | 31; N/a; N/a | Alcohol-related BI | To review the literature on the needs of people with ARBI | Provider expertise, integrated care, adequacy | |

| Kivunja et al. (2018); N/A | Review | 31; N/a; N/a | TBI | To synthesise the literature on the experiences of giving or receiving care for TBI for people with TBI, their family members and nurses in hospital and rehabilitation settings | Navigable system, partnership, opportunity, integrated care, adequacy, interpersonal qualities | |

| Turner et al. (2008); N/A | Review | 50; N/a; N/a | Transition from hospital home; ABI | The primary purpose of this paper is to review the current literature relating to the transition from hospital to home for individuals with ABI | Integrated care, navigable system | |

Synthesis of this literature illustrates the importance of the relationship between the service provider and user when conceptualising appropriate access from the perspectives of people with brain injury. Features of these services and providers such as expert knowledge and their interpersonal qualities, adaptability and collaborative partnerships with providers have emerged as important factors when understanding appropriate access for brain injury. Synthesis of the themes are outlined below.

Provider Expertise. First, review of the studies suggests that service provider knowledge is an important feature of the access experience for people with brain injury. These studies illustrate that service providers with specialised knowledge of brain injury, such as neuropsychologists, are highly valued (Braaf et al., 2019; Brighton, Traynor, Moxham & Curtis, 2013; Dams-O’Connor, Landau, Hoffman & De Lore, 2018; Solovieva & Walls, 2014). Specialised knowledge increased the confidence that service users had in the providers’ expertise, and validation from providers about personal concerns being known consequences of brain injuries was valued (Lexell, Alkhed & Olsson, 2013; Snell, Martin, Surgenor, Siegert & Hay-Smith, 2017). Service users were also likely to have their needs met, and therefore have a good fit of services, when their providers had the brain injury-specific expertise.

Braaf et al. (2019) found that specialised knowledge of severe TBI was highly valued and resulted in more perceived productive interactions by patients with their health and rehabilitation providers. Not only was this expertise valued, people with TBI also emphasised that a lack of brain injury-specific knowledge was problematic. In circumstances where providers lacked expert knowledge, service users were likely to perceive that their issues were not acknowledged or addressed (Braaf et al., 2019). This emphasis on specific expertise also emerged in populations within brain injury, such as those with alcohol-related brain injury who valued knowledge specific to their concerns (Brighton et al., 2013).

Results of the reviewed studies further support this finding that a lack of specialised brain injury-specific expertise is problematic for people with ABI (Eliacin, Fortney, Rattray & Kean, 2018; Harrison et al., 2017; Brauer, Hay & Francisco, 2011). When considering appropriate access for people with ABI, results suggested that lack of access to specialised, age appropriate health services in the community was a significant issue (Eliacin et al., 2018). The unwillingness of general and specialty care providers to learn more about ABI was also perceived as highly problematic (Dams-O’Connor et al., 2018). This work suggests that providers with specialised or injury-specific knowledge are a valued aspect of appropriate access. Specifically, specialised knowledge was important when it came to people with ABI feeling that their needs were being acknowledged or addressed.

Interpersonal Qualities. Interpersonal qualities of providers were an important aspect of appropriate access from service users’ perspectives. This specifically included qualities such as empathy, sensitivity, honesty, and respect (Braaf et al., 2019; Dwyer, Heary, Ward & MacNeela, 2019; Hooson, Coetzer, Stew & Moore, 2013; Kivunja et al., 2018; Lefebvre & Levert, 2012). Gill, Wall and Simpson (2012) found that participants valued the trustworthiness and reliability of staff, which impacted on a positive relationship between the service user and provider. The empathetic nature of the provider was important to service users (Hooson et al., 2013; Kivunja et al., 2018; Lefebvre & Levert, 2012). When providers demonstrated care and understanding of the service users concerns, the service users felt that they were able direct the sessions based on their needs (Braaf et al., 2019). Findings of another study outlined that that good communication was the most valued skill of providers to those with ABI, particularly good communication involving listening and explaining medical terms (Dams-O’Connor et al., 2018).

In contrast, a lack of interpersonal skills was found to be problematic. Chamberlain (2006) reported that concerns about professionals treating them with distrust, and a lack of empathy when concerning ‘invisible symptoms’, such as headaches. Another study found that distrust exhibited by providers regarding symptoms resulted in service users feeling their integrity and self-esteem was impacted (Snell et al., 2017). While the ability of a provider to ensure the service user feels acknowledged in itself is important, the focus placed on trust, and acknowledging invisible symptoms that emerges in the literature seems to intersect with provider expertise. Knowledge and the validation and acknowledgement of brain injury-specific symptoms appears critical.

Sensitivity emerged as a valued quality, particularly when delivering bad news (Dwyer et al., 2019). Review of the studies indicate that this lack of sensitivity on part of the health professionals often resulted in the diminishing of individuals hope (Chamberlain, 2006). The importance of qualities which foster a good relationship between the service user and provider points to the importance of an ongoing relationship with the provider (Braaf et al., 2019; Brauer et al., 2011; Rusconi & Turner-Stokes, 2003; Simpson, Mohr & Redman, 2000; Winkler, Farnworth, Sloan & Brown, 2011). The results of the reviewed studies indicate that service users valued ongoing treatment with a single provider that they had developed a relationship with, and therefore understood their history and progress. Likewise, lack of an ongoing relationship with a provider emerged as challenging. Findings of one study outlined that high levels of changeover in staff resulted in the inability to implement recommended rehabilitation advice, prescribed to reduce pain in an individual with severe ABI (Winkler et al., 2011). The importance of provider interpersonal skills are highlighted by resultant impacts to the service user. A lack of trust and knowledge of their previous history may result in recommendations not being adhered to, or service users not feeling enabled to ask questions which can best facilitate their recovery.

Synthesis of the literature suggests that the impact of provider interpersonal qualities on service user experience can be exacerbated in people from different cultures, service users already at more risk of experiencing social isolation and stigma (Mbakile-Mahlanza, Manderson & Ponsford, 2015; Simpson et al., 2000). Simpson et al. (2000) conducted a study in Australia interviewing people with TBI and their families from Italian, Lebanese and Vietnamese backgrounds. Participants reported a lack of sensitivity on behalf of the providers, and some valued interpersonal qualities such as friendliness or attentiveness more so than providers experience or expertise. This points to the importance of cultural competency of providers when defining appropriateness.

Partnership. The third prevalent theme relating to characteristics of providers was the partnership between the service user and provider. Importantly, the partnership was integral to the experience of choice and control within the interaction and whether there was a sense of appropriateness. This included the ability of the provider to foster a relationship that emphasised collaborative care with the service user being actively involved in decisions and goals of their care. Partnership emerged as a key factor in facilitating return to work. The reviewed studies emphasised that communication and transparency between the provider, the service user and the employer created a partnership which was crucial for successful return to work (Matérne, Lundqvist & Strandberg, 2017; Soeker, Van Rensberg & Travill, 2012). This suggests that good partnerships can assist in the management of challenges across the continuum.

Gill et al. (2012) found that service users with ABI valued when providers offered suggestions based on the service users interests and gave the service user the choice of whether to engage with this recommendation. The service users felt their autonomy was valued by staff who utilised these tactics and reported a positive, collaborative relationship with them as a result. This is corroborated by other reviewed literature suggesting that the ability of the staff to facilitate autonomy in service users with ABI was viewed as a positive quality (Lefebvre, Pelchat, Swaine, Gelinas & Levert, 2005; Martin, Levack & Sinnott, 2015; Soeker et al., 2012).

In contrast, providers who take an authoritative approach can contribute to a poor access experience. Abrahamson et al. (2017) reported that service users felt frustrated as they were unsupported in their attempts to take control of their rehabilitation. This was reflected in the mismatch between the goal focus of professionals in contrast to service users. For example, professionals often focusing on short term goals, whilst service users desired to focus on the long-term goals. This issue with lack of control is evidenced by mismatched expectations between service users and providers specifically the acceptable distances to travel for therapies and reasonable lengths of time (Copley et al., 2013). Conneeley (2012) reported that people with ABI feel that gains in their cognitive awareness over time were not reflected in greater responsibility or autonomy over rehabilitation decisions. This result is supported by Maratos et al. (2016) findings that people with brain injury feel they can be constrained by the clinicians’ expectations as opposed to their abilities. Research has indicated that some people with ABI experienced providers being ‘overprotective’ and ‘clingy’ and treating them as ‘disabled’, which would result in the service user feeling disempowered (Glintborg, Thomsen & Hansen, 2018; Strandberg, 2009). Jumisko, Lexell and Soderberg (2007) found that service users reported that providers would be deliberately evasive when asked for additional information about their treatment, prognosis or asked for more rehabilitation. This resulted in a perceived poor relationship between the service user and provider.

This literature supports the need for patient directed care, when it comes to what is appropriate. Those with an ABI are often thrust into a role where decisions are being made for them not by them early on, due to injury and health professionals attitudes (Lefebvre et al., 2005). The literature suggests that service users are more likely to engage actively with their care and rehabilitation when they are involved in the decisions and understand its purpose. Service users value being included and empowered, and the onus is on the providers to continue to attempt to do this across their recovery.

Adaptability. The fourth valued characteristic of providers is the extent to which providers are willing to accommodate varying service user needs and preferences in how they provide services, namely, the adaptability of the providers. This characteristic often coincided with provider expertise, suggesting that providers who have brain injury-specific knowledge are aware of the ongoing needs and more likely to make accommodations (Braaf et al., 2019; Brauer et al., 2011; Dams-O’Connor et al., 2018). Dams-O’Connor et al. (2018) found that patients with ABI valued providers adapting service provision to their specific needs, which included cognitive or memory limitations. The experiences reported in the research suggested the importance of providers who were willing to adapt the environment such as providing dimmed lighting or ensuring additional reminders of upcoming appointments (Dams-O’Connor et al., 2018). Participants suggested that when providers made these accommodations it facilitated their ability to keep appointments and follow through with provider recommendations. Other physical accommodations are also valued, including adapting service timing (Jumisko et al., 2007) or the willingness to conduct sessions from the service user’s home, which was outlined in some Australian studies (Chan, 2008; Doig, Fleming, Cornwell & Kuipers, 2011; Hall et al., 2012). Doig et al. (2011), interviewed people with TBI, their caregivers and occupational therapists soon after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation, and found that service users preferred to receive treatment at home as it gave them a sense of ownership of their therapy. Service users reported that this accomodation allowed caregivers to be involved and also avoided the trauma that could be triggered by being in a hospital setting (Doig et al., 2011). The theme of adaptable provision also emerged in regards to the timing of services, with emphasis on the importance of participant readiness for services, and therefore the need for services to be adaptable to the service user (Copley et al., 2013; O’Callaghan, McAllister & Wilson, 2012b). The emphasis on adapting the model of provision was evident in the reviewed literature. The more adaptable services seem to result in increased opportunity to fit services to need and subsequently, more likelihood of maintaining engagement of the service user.

Characteristics of the service systems have an impact on the experiences and perceptions of access, both in terms of what is realised and whether it is matched to service users’ needs. Synthesis of the themes are outlined below.

Navigable system. When considering the appropriateness of their access experience, being enabled to locate and navigate access according to needs was highlighted in several studies on experiences of people with ABI. A central feature of this was being informed. Research indicated that information about services was not provided consistently throughout the recovery trajectory and that often the information was insufficient (Dams-O’Connor et al., 2018; Graff, Christensen, Poulsen & Egerod, 2018; Schulz-Heik et al., 2017). The literature reflected that service users felt they were often provided with extensive information during inpatient rehabilitation; however, this stopped after discharge (Hall et al., 2012; Rusconi & Turner-Stokes, 2003). This poses a significant problem given the memory deficits common in early stages of recovery of ABI. One study’s findings relayed suggestions from service users that additional written resources that might ensure the information was assessable later in recovery trajectories (Hall et al., 2012).

The literature emphasised that service users perceived a general lack of information about where to go for rehabilitation, or further information about the rehabilitation (Graff et al., 2018; Harrington, Foster & Fleming, 2015; Pickelsimer et al., 2007). Graff et al. (2018) suggested that people with TBI felt a lack of transparency at an organisation level, such that there was no information on where to find appropriate rehabilitation, whom to contact about duration of symptoms or when to return to work. The study findings indicated participants felt that often those with severe TBI were supported to access care after discharge from hospital, for example they were allocated a case worker. However, those with moderate or mild TBI felt they were left to attempt to manoeuvre the system alone. Another study further supported the emphasis on the utility of the case management role to facilitate service users’ access, however, found that only five participants were receiving this support at three months post-discharge (Turner, Fleming, Ownsworth & Cornwell, 2011a). This research emphasises the need for provider and service-driven follow-up and continuity, with service users not feeling equipped to seek and utilise the information that is required and reporting they have to ‘chase the care’ to receive the services and support they need (Hyatt, Davis & Barroso, 2014).

Integrated care. Integrated care was a further feature of appropriate personal experiences of access. Ongoing provision of service throughout the recovery trajectory was a valued element of access (Hooson et al., 2013; Lefebvre & Levert, 2012; Strandberg, 2009). This research suggested that people with ABI often felt their care was disjointed. In particular, studies exploring experiences in the first year after discharge in Australia revealed that service users often experienced a lack of continuity from the hospital to the community (Chamberlain, 2006; Hall et al., 2012; Turner et al., 2007; Turner, Fleming, Ownsworth & Cornwell, 2008, 2011a, 2011b). The period of time moving back into the community from in-patient rehabilitation has been shown to be a critical time, in which appropriate available services can facilitate transitions (Turner et al., 2007; Turner et al., 2008). Results of a study by Turner et al. (2011a) suggested that the organisation of ongoing post-acute care services was often not completed as part of the discharge preparation process, and therefore families were often required to do this themselves, resulting in delays. These delays in service provision in those with ABI can result in the exacerbation of existing problems (Copley et al., 2013; Leith, Phillips & Sample, 2004; O’Callaghan et al., 2012a, 2012b). The reviewed literature emphasised that service users’ needs are often time-dependent, one study found that support with guidance and planning was often vital right after discharge (Rotondi, Sinkule, Balzer, Harris & Moldovan, 2007).

Additionally, the reviewed research suggests that integration of care between providers is a issue for the appropriate access of people with ABI (Braaf et al., 2019; Dams-O’Connor et al., 2018; Lefebvre & Levert, 2012; Strandberg, 2009). In one study participants indicated that they were able to effectively solve problems that emerged during their healthcare through medical providers collaborating on a care plan, discussing medication needs, or being referred to specialists who maintained regular contact with the referring provider (Dams-O’Connor et al., 2018).

Results of the reviewed literature indicated a need for a care coordinator. The literature suggested that service users would value a key contact, coordinator or case manager to assist with communicating with all the services, ensuring collaboration between providers (Braaf et al., 2019; Copley et al., 2013; Dams-O’Connor et al., 2018; Graff et al., 2018; Hyatt et al., 2014; Umeasiegbu, Waletich, Whitten & Bishop, 2013). However, this literature indicates that people with ABI are rarely able to have access to someone who would take on this role. Frequently it emerged that those who had caregivers, to advocate on their behalf, felt they were able to access the care they needed and supplement this lack of a key contact (Copley et al., 2013; Graff et al., 2018; Harrington et al., 2015; Harrison et al., 2017).

Adequacy. Adequacy of services received emerged as a theme in the literature. Inconsistency in the quality and sufficiency of provision from service providers was evident as a key issue when considering appropriate access for those with an ABI. The reviewed literature suggests that service users perceived varied quality in services they received and that providers were inconsistent in the level of effort they demand from service users, often resulting in poor improvement (Brauer et al., 2011; Rotondi et al., 2007). One study found that people with moderate and severe ABI described a mismatch between service users’ needs and clinician focus, in that often clinicians would focus on the physical and practical issues, resulting in service users with a lack of psychological support (Glintborg et al., 2018). Aligning with this, a study in war veterans reported that service users felt that providers were often treating symptoms as opposed to addressing the cause of the issues, which resulted in service users feeling the treatment was ineffective (Hyatt et al., 2014).

In addition to quality, sufficiency in the quantity emerged as important. Service users felt they accessed less than what they perceived they needed for maximal recovery, which ultimately resulted in these services failing to meet their needs (Braaf et al., 2019; Gill et al., 2012; Lexell et al., 2013; Turner et al., 2011a; Umeasiegbu et al., 2013). This aligns with concerns around receiving the right service at the right time. One component of receiving the right service at the right time is the fit of the service to the need of the service user. The ability to provide service users with this service when needed is reliant on the current system waiting and response times. The literature suggests that service users experience significant waiting times to access the services they need (Glintborg et al., 2018), and unexplained delays in service commencement after services have been approved (Abrahamson et al., 2017; Leith et al., 2004; Turner et al., 2011a). The notion of the right service at the right time, including the perceived intensity and frequency of services, echoes the emphasis on how the ideal of service user choice and control can be difficult to achieve in practice. The ability to provide service users with the right service at the right time is enabled by both system and individual-level factors. Research in this area suggests that not only is optimal care facilitated by access to the right service, but access to this service based on the individual’s recovery timeline and at their own pace at the right dose.

Opportunity. Opportunity to access appropriate services was reflected in experiences of those who were unable to access resources in particular areas, particularly regional and rural areas due to lack of availability (Dams-O’Connor et al., 2018; Keightley et al., 2011; Mitsch, Curtin & Badge, 2014). This lack of opportunity of access also emerged with regards to funding (Braaf et al., 2019; Harrington et al., 2015; Leith et al., 2004; O’Callaghan et al., 2010). Those receiving different funding were given the opportunity to access different services and different dosage of services, as opposed to accessing the services depending on their needs (Braaf et al., 2019; O’Callaghan et al., 2010). Research emphasises that often service users were restricted from accessing speciality providers due to funding restrictions, cost and transportation (Dams-O’Connor et al., 2018; Maratos et al., 2016; Toor et al., 2016; Umeasiegbu et al., 2013). Research conducted in the USA has consistently reported that people with a TBI, are often denied access due to rigid service criteria, and policies (Leith et al., 2004; Pickelsimer et al., 2007; Wyse, Pogoda, Mastarone, Gilbert & Carlson, 2020). In addition to being denied the opportunity to access to needed services, the research indicated that there is often a lack of opportunity to access appropriate resources altogether. Several studies revealed that often young people with an ABI were forced to receive care from nursing homes, as these were the only available facilities that could accommodate their needs (Eliacin et al., 2018; Graff et al., 2018; Winkler et al., 2011). In an Australian study, interviews were undertaken with those who had transitioned from an aged care facility to community-based accommodation (Winkler et al., 2011). Results suggested that when enabled to access more appropriate services, service users were able to make significant improvements in functional life skills, for example being able to regain continence, and engage in feeding themselves, as opposed to using feeding tubes and adult continence pads.

The need for opportunity to access appropriate resources emerged in several studies, which found that often the providers and resources available were not available in specific languages for people with brain injury, and there was no availability of translating services (Keightley et al., 2011; Mbakile-Mahlanza et al., 2015; Mitsch et al., 2014). Likewise, there was a lack of culturally sensitive access for people with brain injury, which may contribute to the often-compounded disadvantage experienced by these groups. This suggests that despite shifts in policies and services aligning with choice and control for service users, and provision of service based on need, people are still limited in their opportunity to access services appropriate to their needs.

Discussion

The current study used a scoping review to identify key characteristics of ‘appropriate’ access, as defined by the personal experiences of adults with ABI to post-acute care services. The present study revealed that while some service users reported positive experiences in receiving services post-discharge, many were not receiving the right fit for their needs. Features of these services and providers such as expert knowledge and their interpersonal qualities, adaptability and collaborative partnerships with providers have emerged as important factors when understanding appropriate access for people with a brain injury. Results highlighted the issues at the system-level pertaining to a lack of communication and cooperation between providers, leaving service users to manage their care on their own. Results revealed a lack of research in the first few months after discharge with a majority of the studies sampling participants with an average of over 1-year post-injury, with some studies sampling participants ranging over 10 years in difference in time post-injury. Additionally, a majority of the review literature was a qualitative design. This highlights that although there is emerging evidence about what is appropriate access to post-acute care services, to verify and elaborate on these findings there is a need for research focused on access in the period after discharge, utilising mixed designs, and addressing both system-level and provider-level factors.

The features of services and providers that emerged as key centred around interpersonal qualities, being collaborative and brain injury-specific knowledge. This supports previous findings that, despite the emphasis on person-centred healthcare, traditional didactic approaches are still used and are problematic for service users (Jackson et al., 2019). Furthermore, a quality relationship appears to underpin subsequent care experiences, resulting in the service user feeling safe and empowered to ask questions and engage in their care which enables them to adhere to recommendations. The sometimes ‘invisible’ nature of brain injury (Chamberlain, 2006), but equally complex presentation, further underscores the importance of quality provider relationships and the importance of specialist knowledge. Memory impairment, fatigue, ‘inappropriate’ or impulsive behaviours, inability to modulate their speech, and lack of self-awareness often manifest following brain injury (Fleminger & Ponsford, 2005; Kumar et al., 2019). Previous literature has emphasised the stigma experienced by those with ABI by community and health professionals alike for ‘malingering’ or deviant ‘mad’ behaviour (Simpson et al., 2000; Simpson, Simons & McFadyen, 2002). The emphasis on expertise reported presently may align with the stigma and inner distress of not having validation for their concerns and needs. This provides key targets of intervention that could improve access experiences for those with ABI. Interpersonal skills, patient-centred care and specialised brain injury knowledge competencies and training might facilitate and improve experiences and outcomes.

Results highlighted the issues around continuity of care evident in the health systems with service users concerns about having a navigable system and integrated care emerging as connected. Service users, who were often unable to find the information or resources to navigate the system on their own, wished for integrated collaborative systems of care to address the gaps and uncertainties across the recovery trajectory. This suggests that the system is unable to provide the road map to services and recovery between providers across the recovery timeline, likely due to health professionals lacking time, incentives and a medium to collaborate on patients care. This seems to be resultant from the structure and process of the ‘inpatient’ versus ‘community care’ rehabilitation model. Whilst changes in policies evidenced by the introduction of schemes such as NDIS and NIIS in Australia have been implemented to increase the choice and control of the service users, the resource-limited nature of services have not been adapted to support this model. The siloed nature of health services often results in a lack of communication and cooperation between providers, leaving service users to manage their care on their own (Rusconi & Turner-Stokes, 2003; Turner et al., 2007). As a result, service users are unequipped to navigate the system and are left unable to design and implement the healthcare that is the best fit for their needs. This is highlighted by the focus in the literature on the value of a key advocate managing the overall care and communication between providers. The role of a key coordinator emerged as important to bridge the existing gap between providers through assisting in care navigation. This suggests the need for a deeper understanding of the mix of services, the roles and relationships between health professionals and the importance of characteristics that people with ABI value in their access experiences.

This review also suggests that opportunity to access services is also integral to a personalised understanding of appropriateness of access. From the review findings, however, there was an evident disparity in the opportunity for access. Some studies reported on the impact of variations in opportunity for age appropriate and culturally sensitive services (Keightley et al., 2011; Simpson et al., 2000; Winkler et al., 2011). The literature also emphasised the disparity in opportunity according to location, particularly less specialised, available, timely services in rural and regional communities (Copley et al., 2013; Eliacin et al., 2018). This disparity relates to the rural health workforce and lack of specialised knowledge of brain injury, due to the difficulty in recruiting and retaining health care professionals in remote geographic locations or due to a rotating system or FIFO (Mitsch et al., 2014). Notably, to enable choice and control, policy can influence the distribution of resources across geographical locations and therefore, the access experiences of people with ABI.

Implications and Recommendations

A significant majority of the work that has been conducted focusing on appropriateness of post-acute care services is qualitative. Whilst providing rich data on personal experiences, there is a need for quantitative data to analyse trends and patterns in larger cohorts (McCusker & Gunaydin, 2015). Quantitative measurement of an individual’s experiences of services and their injury is challenging. Much of the quantitative work uses measures of met and unmet needs, and facilitators and barriers to services to capture information about post-acute service access (Pickelsimer et al., 2007; Schulz-Heik et al., 2017; Solovieva & Walls, 2014; Toor et al., 2016). However, research concentrating on needs assessments in this population has primarily focused on the emotional, cognitive and social needs rather than the provision of services that may occur in response to those needs (Andelic, Soberg, Bernsten, Sigurdardottir & Roe, 2014). This work provides some insight into the unmet needs of this population, however, it still fails to capture the complexity around the fit for need of the mix of services for the service user and their experience of adequacy of services received. A more in-depth conceptualisation of met and unmet needs is needed to begin to understand the complexity of access in this population.

This review illustrated that despite the knowledge base emphasising the first six months after discharge as critical targets for ongoing recovery, and typically challenging times for those with ABI, there is a dearth of research exploring the access experiences of people with a ABI in the months after discharge (Nalder et al., 2012; Turner, Fleming, Cornwell, Haines & Ownsworth, 2009). A majority of the studies sampled participants with an average of over 1-year post-injury, with some studies sampling participants ranging over 10 years in difference in time post-injury (Eliacin et al., 2018). Given the themes relating to the changes in information and support needs over time, longitudinal research focusing on the early stages after discharge seems to be needed.

Results of this review highlight the need to address characteristics at the structural and policy level, through further targeted research and service user input at the design level. Since the implementation of the NDIS in Australia, there is increasing interest in the evaluation of such schemes and the subsequent impact on those with disability. Further research is needed to explore the utility of funding schemes in terms of personalised appropriateness of access for those with ABI. Analysis in relation to country and policies was beyond the scope of the present work. This is a limitation and further research into the implications of country and policies are needed to fully understand the systemic impact.

Limitations

The limitations of utilising a scoping review mean that it is possible that some articles were missed. Studies in Australia had the highest proportion of those included in this scoping review, this could potentially be resultant of missed articles due to international terms. Due to the complex nature of the concept of access, there is a vast range of terms for services and experiences. This can result in difficulties developing an expansive list of search terms. To address this a rigorous method and a range of search terms and criteria were utilised to ensure the review was able to capture the related articles. The present article targeted articles focusing on acquired brain injury and therefore did not use specific terms such as ‘stroke’. Therefore articles only referring to the sample as people with stroke may have been missed. Additionally, only English articles were included. Given that access issues around culturally appropriate services emerged, it is possible that there is work in other languages that may be relevant. Consistent with the chosen methodology, articles were not formally appraised for quality, so there are limitations to the strength of conclusions drawn from the body of work.

Conclusions

Findings from this scoping review highlight a multitude of factors that characterise appropriate access based on the service access experiences and opportunities of adults with ABI after leaving inpatient rehabilitation. Whilst a critical appraisal was beyond the scope of this study, there were a range of aims and designs which were identified, and high variability in the sample sizes, the time since injury and discharge. This demonstrates that although there is emerging evidence about what is appropriate access to post-acute care services, to draw conclusions there is a need for rigorous, research, particularly focused on access in the period after discharge, utilising mixed designs, longitudinal follow-up, and addressing both system-level and provider-level factors.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Kirstyn Laurie is supported by a Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Stipend Scholarship.

Conflicts of interest

Kirstyn Laurie has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Michele Foster has not conflicts of interest to disclose. Louise Gustafsson has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

Abrahamson V., Jensen J., Springett K., Sakel M. (2017) Experiences of patients with traumatic brain injury and their carers during transition from in-patient rehabilitation to the community: A qualitative study. Disability and Rehabilitation 39(17), 1683-1694.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Andelic N., Soberg H. L., Berntsen S., Sigurdardottir S., Roe C. (2014) Self-perceived health care needs and delivery of health care services 5 years after moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 6(11), 1013-1021.

| Google Scholar |

Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005) Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8(1), 19-32.

| Google Scholar |

Braaf S., Ameratunga S., Christie N., Teague W., Ponsford J., Cameron P. A., Gabbe B. J. (2019) Care coordination experiences of people with traumatic brain injury and their family members in the 4-years after injury: A qualitative analysis. Brain Injury 33(5), 574-583.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Brauer J., Hay C. C., Francisco G. (2011) A retrospective investigation of occupational therapy services received following a traumatic brain injury. Occupational Therapy Health Care 25(2-3), 119-130.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Brighton R., Traynor V., Moxham L., Curtis J. (2013) The needs of people with alcohol-related brain injury (ARBI): A review of the international literature. Drugs and Alcohol Today 13(3), 205-214.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bryan-Hancock C., Harrison J. (2010) The global burden of disease project 2005 methods utilised by the injury expert group for estimating world-wide incidence and prevalence rates. Injury Prevention 16(Suppl 1), A99.

| Google Scholar |

Buntin M. B. (2007) Access to postacute rehabilitation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 88(11), 1488-1493.

| Google Scholar |

Chamberlain D. J. (2006) The experience of surviving traumatic brain injury. Journal of Advanced Nursing 54(4), 407-417.

| Google Scholar |

Chan J. (2008) What do people with acquired brain injury think about respite care and other support services? International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 31(1), 3-11.

| Google Scholar |

Collie A., Prang K. (2013) Patterns of healthcare service utilisation following severe traumatic brain injury: An idiographic analysis of injury compensation claims data. Injury 44(11), 1514-1520.

| Google Scholar |

Conneeley A. L. (2012) Transitions and brain injury: A qualitative study exploring the journey of people with traumatic brain injury. Brain Impairment 13(1), 72-84.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Copley A., McAllister L., Wilson L. (2013) We finally learnt to demand: Consumers’ access to rehabilitation following traumatic brain injury. Brain Impairment 14(3), 436-449.

| Google Scholar |