Do Australian sexual health clinics have the capacity to meet demand? A mixed methods survey of directors of sexual health clinics in Australia

Christopher K. Fairley A B * , Jason J. Ong A B C , Lei Zhang

A B * , Jason J. Ong A B C , Lei Zhang  A B , Rick Varma

A B , Rick Varma  D , Louise Owen E , Darren B. Russell F G H , Sarah J. Martin

D , Louise Owen E , Darren B. Russell F G H , Sarah J. Martin  I J , Joseph Cotter K , Caroline Thng

I J , Joseph Cotter K , Caroline Thng  L , Nathan Ryder

L , Nathan Ryder  M N , Eric P. F. Chow

M N , Eric P. F. Chow  A B O # , Tiffany R. Phillips

A B O # , Tiffany R. Phillips  A B # and

A B # and A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Handling Editor: Matthew Hogben

Abstract

The study describes the capacity of publicly funded sexual health clinics in Australia and explores the challenges they face.

We sent a survey to the directors of publicly funded sexual health clinics across Australia between January and March 2024. The survey asked about how their clinics were managing the current clinical demand.

Twenty-seven of 35 directors of sexual health clinics responded. These 27 clinics offered a median of 35 (IQR: 20–60) bookings each day, but only a median of 10 (IQR: 2–15) walk-in consultations for symptomatic patients. The average proportion of days that clinics were able to see all patients who presented with symptoms was 70.1% (95% CI 55.4, 84.9) during summer versus 75.4% (95% CI 62.2, 88.5) during winter. For patients without symptoms, the corresponding proportions were 53.3% (95% CI 37.9, 68.8) during summer versus 57.7% (95% CI 41.7, 73.7) during winter. If these percentages were adjusted for the number of consultations that the clinic provided, then the corresponding numbers for symptomatic individuals was 51.0% for summer and 65.2% for winter, and for asymptomatic individuals it was 48.1% and 49.8%, respectively. The catchment population of the clinics for each consultation they provided ranged from as low as 3696 to a maximum of 5 million (median 521,077).

The high proportion of days on which sexual health clinics were not able to see all patients is likely to delay testing and treatment of individuals at high risk of STIs and impede effective STI control.

Keywords: capacity, chlamydia, control of sexually transmitted infections, demand, gonorrhoea, HIV, sexual health clinics, survey, syphilis, 2023.

Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have risen steadily over the past 20 years in Australia and overseas. In 2023, there were 110,032 diagnoses of chlamydia, and 5290 diagnoses of infectious syphilis in Australia.1 Particularly concerning are the increasing cases of infectious syphilis among women with parallel rises in congenital syphilis, which are now at their highest level since records surveillance began in 2003.1,2

Access to health care for sexual health (SH) services is primarily provided by general practitioners who are supported by a network of SH clinics that were originally funded for return service men after World War I.3 General practices in Australia are funded by the Federal Government through a fee for service insurance scheme know as Medicare.4 The patient may also have to pay a fee for each service in addition to the funding from Medicare. SH clinics are free for attendees and are funded by State Governments.4 The number of SH clinics and, therefore, their geographic access vary significantly between states, with New South Wales having the largest number, and Victoria having essentially a single, albeit large, clinic based in the capital city.4 SH clinics generally provide services preferentially to higher-risk individuals.4 More recently, Internet-based services have developed and provide laboratory test requests for STI testing through Medicare, but these are for screening for asymptomatic individuals.5

Access to health care is the most important factor that determines the incidence of STI within populations, and is a considerably more effective intervention for controlling STIs than interventions to change behaviour.5 Limited access to health care increases the reproductive rate and incidence of both HIV and STIs by prolonging the duration of the infectious periods.5 Given the rising rates of STIs in Australia, it is reasonable to ask the question whether the current SH services are ‘accessible’ to the public, particularly for individuals with symptomatic STIs who have recently acquired their infection and benefit most from immediate treatment.5,6 Inadequate access to health care creates a vicious cycle, where poor access to services results in more STIs, which reduce access further, and then STIs rise in response to this reduced healthcare access. This situation in Australia is further complicated by the growing difficulty in accessing general practices and reduced rates of bulk billing, which is where patients do not pay to see general practitioners. In Australia, general practitioners provide primary care for all medical conditions that include individuals with STIs.7,8 The inadequate number of general practitioners in Australia had led general practices in some areas to not accept any new patients who have not previously been seen in the clinic, leaving individuals with STI symptoms or asymptomatic individuals requiring screening with limited alternatives for care other than SH clinics.9

The aim of the study was to understand the current capacity of publicly funded SH clinics in Australia to meet patient demand and to explore challenges faced by the SH clinics.

Methods

Study design, setting and population

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of directors of publicly funded SH clinics in Australia. We used the Australian Society of HIV, Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine and State Governments contacts to compile a list of public SH clinics. We invited the directors of these 35 SH clinics to participate in the survey. These included 14 in New South Wales, 13 in Queensland, two in Victoria, one in Tasmania, two in Western Australia, one in South Australia, one in Northern Territory and one in Australia Capital Territory. The directors were asked about the calendar year 2023. Summer was from 1 December to 28 February. Winter was from 1 June to 31 August.

Survey items and distribution

We developed the survey using Qualtrics10 and administered it online between January and March 2024. The survey consisted of 37 questions, including multiple-choice questions, Likert-scale items and open-ended questions. Topics included demographics of the SH clinics, patient load data, types of clinics and challenges faced in managing patient load. Participants were informed that their names and those of clinic would not be disclosed in any publications without their consent. A participant information sheet was provided on the first page of the survey, and participants provided consent prior to completing the survey. Up to three reminder emails were sent over a 4-week period to the invited SH clinics to encourage completion of the survey.

Ethical considerations

This project was approved by Alfred Hospital Ethics Committee (project number 669/23).

Data analyses

Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables, whereas medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were used for continuous variables. Data analyses were performed using SPSS version v29 (IBM). We weighted the proportion of days that clinics were able to see all patients by the size of the clinic. Free text data were analysed using a conventional content analysis approach, suitable for describing phenomena such as participants’ perceived challenges and recommendations on capacity building. RK initially read and re-read the free text responses in their entirety, creating an initial set of codes inductively from the data. RK then met with TP to review and refine the coding framework. The final coding structure was used to inform the results of the study.

Results

Characteristics of participating SH clinics

Twenty-seven of 35 clinics (77.1%) consented to participate in the study. Tables 1 and 2 describe the characteristics of these clinics and the services they provide. The clinics provided a median of 4500 (IQR 1762–7710) consultations per year, and served a median population of 521,077 (IQR 250,000–1,000,000). The median number of consultations provided per 100,000 head of population was 877 (IQR 193–2380), with a minimum of 34.

| Characteristic | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sate or territory | ||

| New South Wales | 11 (40.7) | |

| Queensland | 8 (29.6) | |

| Western Australia | 2 (7.4) | |

| Victoria | 2 (7.4) | |

| South Australia | 1 (3.7) | |

| Australian Capital Territory | 1 (3.7) | |

| Tasmania | 1 (3.7) | |

| Northern Territory | 1 (3.7) | |

| Services provided | ||

| Telehealth services | 27 (100.0) | |

| HIV testing | 27 (100.0) | |

| HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis | 27 (100.0) | |

| HIV post-exposure prophylaxis | 27 (100.0) | |

| Antiretroviral therapy for patients with HIV | 27 (100.0) | |

| STI testing | 27 (100.0) | |

| STI treatment | 27 (100.0) | |

| Contact tracing (syphilis and HIV) | 27 (100.0) | |

| Outreach | 22 (81.5) | |

| Health promotion | 17 (63.0) | |

| Specific clinics that are only for sex workers | 7 (25.9) | |

| Specific clinics that are only for MSM | 3 (11.1) | |

| Other services A | 20 (74.1) | |

| Characteristic | Median (IQR) | |

| Population of catchment area | 521,077 (250,000–1,000,000) | |

| No. of new diagnoses in 2023 | ||

| HIV | 7 (3–15) | |

| Infectious syphilis | 43 (25–104) | |

| Gonorrhoea | 133 (63–346) | |

| Mycoplasma genitalium | 40 (20–62) | |

| Trichomonas | 6 (3–20) | |

| Chlamydia | 261 (281–546) | |

| Staffing levels (FTE) | ||

| Nurses | 4.2 (3.2–8.1) | |

| Doctors | 3.2 (1.0–6.0) | |

| Counsellors | 0.0 (0.0–1.4) | |

| Laboratory technicians | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | |

| Pharmacists | 0.0 (0.0–0.3) | |

| Contact tracing support officers | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | |

| Health promotion | 0.0 (0.0–1.1) | |

| Dietician | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | |

| Social worker | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | |

| Nurse practitioners | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | |

FTE, full time equivalent; IQR, interquartile range; STI, sexually transmitted infection; MSM, men who have sex with men.

| No. of clients 2023 | HIV n (%) | Syphilis n (%) | Gonorrhoea n (%) | Mycoplasma n (%) | Trichomoniasis n (%) | Chlamydia n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (8.2) | 7 (11.5) | |

| 500 | 5 (1.0) | 12 (2.4) | 40 (8.0) | 12 (2.4) | 12 (2.4) | 120 (24.0) | |

| 800 | 2 (0.3) | 20 (0.3) | 40 (5.0) | 10 (1.3) | 40 (5.0) | 50 (6.3) | |

| 1131 | 5 (0.4) | 11 (1.0) | 42 (3.7) | 5 (0.4) | 3 (0.3) | 171 (15.1) | |

| 1300 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 1700 | 6 (0.4) | 40 (2.4) | 70 (4.1) | 28 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 84 (4.9) | |

| 1783 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| 2500 | 3 (0.1) | 50 (2.0) | 62 (2.5) | 40 (1.6) | 10 (0.4) | 240 (9.6) | |

| 3000 | 0 (0.0) | 25 (0. 8) | 96 (3.2) | 73 (2.4) | 1 (0.0) | 250 (8.3) | |

| 3000 | 7 (0.2) | 60 (2.0) | 200 (6.7) | 25 (0.8) | 6 (0.2) | 271 (9.0) | |

| 3600 | 7 (0.2) | 45 (1.3) | 111 (3.1) | 34 (0.9) | 3 (0.1) | 211 (5.9) | |

| 4200 | 23 (0.5) | 160 (3.8) | 391 (9.3) | 47 (1.1) | 20 (0.5) | 532 (12.7) | |

| 4500 | 16 (0.4) | 59 (1.3) | 211 (4.7) | 23 (0.5) | 7 (0.2) | 305 (6.8) | |

| 4500 | 8 (0.2) | 25 (0.6) | 180 (4.0) | 20 (0.4) | 5 (0.1) | 220 (4.9) | |

| 4500 | 2 (0.0) | 25 (0.5) | 9 (0.2) | N/A | 5 (0.1) | 58 (1.1) | |

| 5000 | 10 (0.2) | 50 (1.0) | 80 (1.6) | 50 (1.0) | 150 (3.0) | 300 (6.0) | |

| 6676 | 12 (0.2) | 91 (1.4) | 353 (5.3) | 58 (0.9) | 4 (0.1) | 514 (7.7) | |

| 7000 | 10 (0.1) | 109 (1.6) | 366 (5.2) | 51 (0.7) | 4 (0.1) | 651 (9.3) | |

| 7000 | 4 (0.1) | 4 (0. 1) | 88 (1.3) | 15 (0.2) | 28 (0.4) | 216 (3.1) | |

| 7500 | 1 (0.0) | 26 (0.3) | 238 (3.2) | 25 (0.3) | 10 (0.1) | 687 (9.2) | |

| 8340 | 5 (0.1) | 30 (0.4) | 64 (0.8) | 40 (0.5) | 75 (0.9) | 250 (3.0) | |

| 12,000 | 25 (0.2) | 500 (4.2) | 500 (4.2) | 250 (2.1) | 0 | 550 (4.6) | |

| 12,092 | 18 (0.1) | 108 (0.9) | 324 (2.7) | 62 (0.5) | 2 (0.0) | 695 (5.7) | |

| 12,344 | 11 (0.1) | 35 (0.3) | 155 (1.3) | 89 (0.7) | 15 (0.1) | 298 (2.4) | |

| 35,000 | 21 (0.1) | 384 (1.1) | 1748 (5.0) | 130 (0.4) | 3 (0.0) | 2187 (6.2) | |

| 37,000 | 45 (0.1) | 450 (1.2) | 2700 (7.3) | 700 (1.9) | 80 (0.2) | 4000 (10.8) | |

| N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Percentages for Mycoplasma genitalium were not included, because it is not routinely tested for and, therefore, the comparison will be invalid.

N/A, data not available.

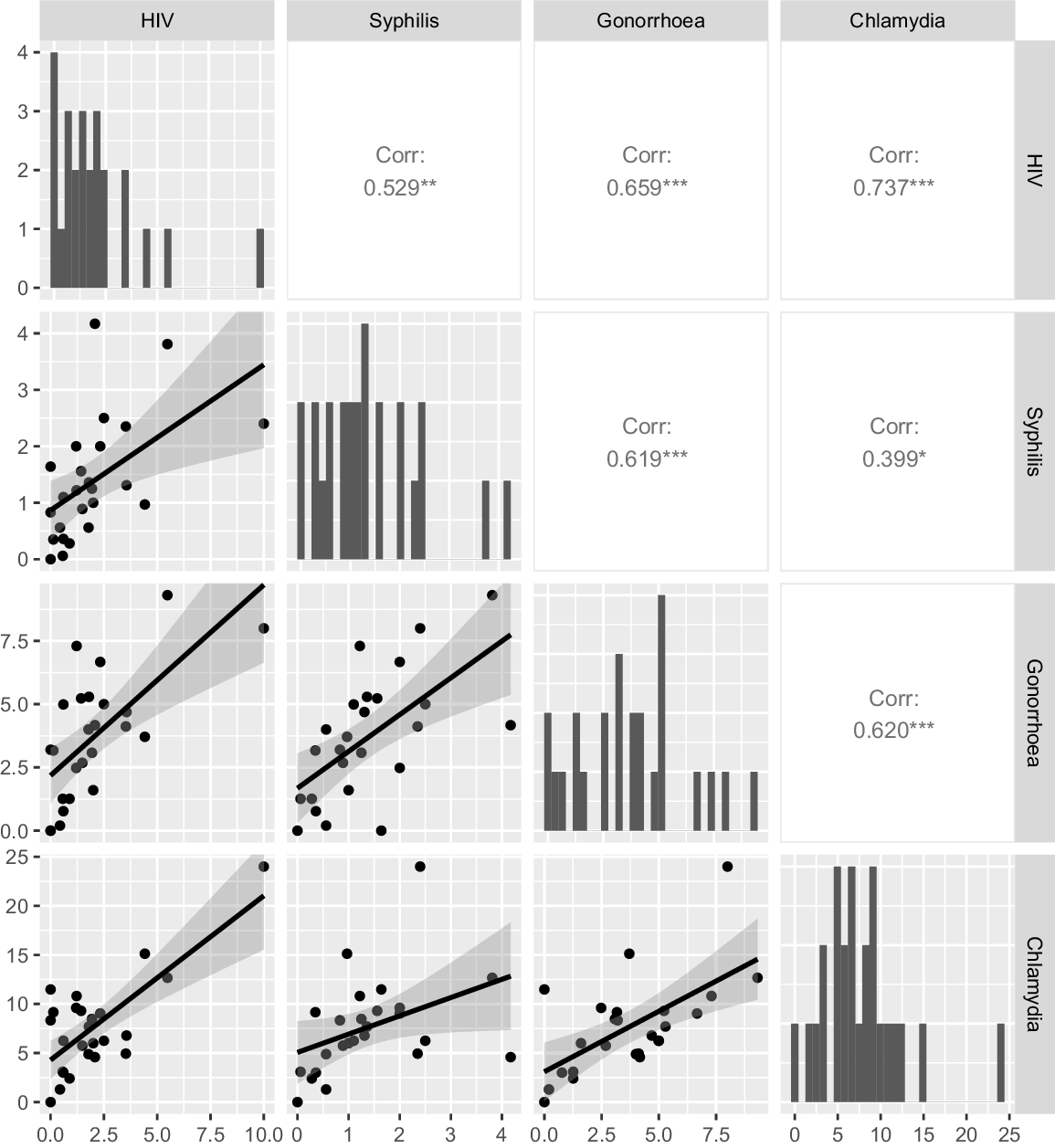

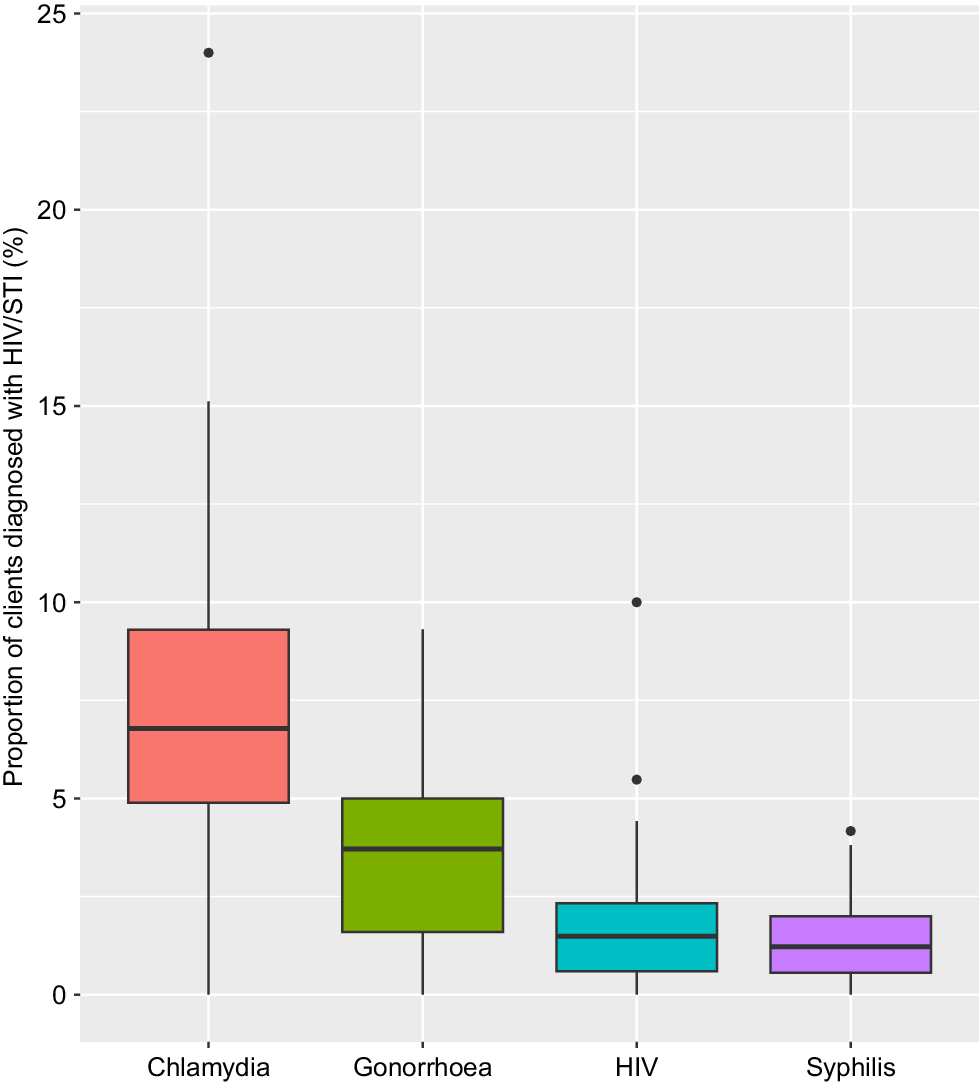

In 2023, clinics diagnosed a median of 261 chlamydia cases, 133 gonorrhoea cases, 43 infectious syphilis cases, 40 Mycoplasma genitalium cases, six trichomona cases and seven HIV cases. The percentiles for the proportion of patients diagnosed with different STIs are shown in Fig. 1. We calculated the ratio of the 75th percentile to the 25th percentile for each infection to provide a measure of the spread of STI risk among patients attending the different clinics. These ratios were 4.1 for HIV, 5.4 for syphilis, 3.6 for gonorrhoea and 2.0 for chlamydia (Fig. 1). There was a strong and highly significant correlation between the positivity for HIV, syphilis, gonorrhoea and chlamydia between different clinics (Table 3, Fig. 2, P < 0.05).

Median and interquartile ranges for proportion of individuals at each clinic with chlamydia, gonorrhoea, HIV (by 10) and syphilis. Footnote: for clarity the proportions of individuals diagnosed with HIV has been multiplied by 10.

| Chlamydia | Gonorrhoea | Syphilis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gonorrhoea | 0.62 (P < 0.001) | |||

| Syphilis | 0.40 (P = 0.048) | 0.62 (P < 0.001) | ||

| HIV | 0.74 (P < 0.001) | 0.66 (P < 0.001) | 0.53 (P = 0.007) |

R-value for Pearson’s correlation and P-value for the correlation.

Characteristics of consultations

The median of 4500 consultations a year was made up of a median of 35 (IQR 20–60) daily booked appointments and 10 (IQR 2–15) daily walk-in consultations (Table 4). The median duration of symptomatic consultations was 30.0 min (IQR 30.0–45.0) and 20.0 min (IQR 15.0–30.0) asymptomatic consultations.

| Characteristic | Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of consultations in 2023 | 4500 (1762–7710) | |

| No. of appointments available each day | 35 (20–60) | |

| No. of consultations available per day for clients to walk-in without an appointment | 10 (2–15) | |

| Duration (min) of a consultation for patients with symptoms of STI | 30.0 (30.0–45.0) | |

| Duration (min) of a consultation for patients with without symptoms of STI | 20.0 (15.0–30.0) | |

| Mean (95% CI) | ||

| Proportion of days the clinic can see all patients with symptoms | ||

| Summer (December–February) | 70.1 (55.4,84.9) | |

| Winter (June–August) | 75.4 (62.2,88.5) | |

| Weighted by clinic size | ||

| Summer (December–February) | 51.0 (50.8,51.2) | |

| Winter (June–August) | 65.2 (65.0,65.3) | |

| Proportion of days the clinic can see all patients without symptoms | ||

| Unweighted | ||

| Summer (December–February) | 53.3 (37.9,68.8) | |

| Winter (June–August) | 57.7 (41.7,73.7) | |

| Weighted by clinic size | ||

| Summer (December–February) | 48.1 (47.9,48.3) | |

| Winter (June–August) | 49.8 (49.7,50.0) | |

Clinics were able to see all symptomatic patients who presented 70.1% of days during summer and 75.4% during winter. Clinics were able to see all asymptomatic patients who presented 53.3% of days during summer and 57.7% of days during winter. When the proportion of days clinics could see all patients was weighted for the number of patients seen at the clinic, the percentages for symptomatic patients was 51.0% for summer and 65.2% for winter, and for asymptomatic patients it was 48.1% for summer and 49.8% for winter.

Prioritisation of different case scenarios

Table 5 shows the likely outcome for five different hypothetical clinical scenarios presenting to the clinics. Most clinics reported that they would be able to see on the same day a high-risk case presenting with clinical features consistent with syphilis, but less than half would be able to see a woman with an uncomplicated vaginal discharge the same day.

| Likely outcome of visit to SHC | Case scenarios 1 to 5 A | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1, n (%) | Scenario 2, n (%) | Scenario 3, n (%) | Scenario 4, n (%) | Scenario 5, n (%) | ||

| Seen as a walk-in on the day | 9 (33.3) | 26 (96.3) | 23 (85.2) | 13 (48.1) | 16 (59.3) | |

| Given a future booked appointment | 11 (40.7%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 11 (40.7) | 8 (29.6) | |

| Not seen and refereed to another service | 6 (22.2%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (3.7) | |

| Unknown | 1 (3.7%) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (7.4) | 2 (7.4) | 2 (7.4) | |

Shortages of staff and inadequate clinic space were the most common issues limiting the provision of services (Table 6).

| Strongly agree n (%) | Somewhat agree n (%) | Neither agree nor disagree n (%) | Somewhat disagree n (%) | Strongly disagree n (%) | Unsure n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shortage of clinic space | 9 (33.3) | 10 (37.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 5 (18.5) | 2 (7.4) | |

| Shortage of staff | 20 (74.1) | 3 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.4) | 2 (7.4) | |

| Staff burnout | 6 (22.2) | 6 (22.2) | 7 (25.9) | 3 (11.1) | 2 (7.4) | 3 (11.1) | |

| Insufficient staff supervision | 2 (7.4) | 7 (25.9) | 4 (14.8) | 5 (18.5) | 7 (25.9) | 2 (7.4) | |

| Cost of services | 4 (14.8) | 4 (14.8) | 5 (18.5) | 3 (11.1) | 9 (33.3) | 2 (7.4) |

Challenges faced by SH clinics

Twenty of the 27 participants provided written free text responses about challenges and opportunities for improvement in their SH clinic. Responses generally fell into two main themes: structural challenges (i.e. staffing, resource and infrastructure challenges) and community challenges (i.e. serving culturally and linguistically diverse patients, and accessibility). There were nuances in the challenges faced between urban and regional or remote clinics. For example, rural SH clinics reported the need for better staff housing and improved transportation for both staff and patients. In contrast, urban clinics focused on issues related to changing patient demographics; for example, the increasing number of migrants without Medicare and increasing demand for PrEP (Table 6). There was also a recognition that inadequate funding for SH services exacerbates both structural and community-level challenges.

Structural challenges were the most reported issues, including understaffing, unfilled positions, insufficient staff coverage during illnesses and a growing population without corresponding increases in staffing levels (Table 7). These problems have heightened pressure on the existing workforce and led to declining staff morale, as workers feel overworked and underappreciated. Moreover, many respondents highlighted significant financial difficulties, such as insufficient funding for SH services and a lack of resources for staff training in SH. These financial constraints are perceived as compromising the ability to manage STIs effectively. A few infrastructure needs were also noted, with calls for increased space in existing SH clinics and the establishment of new clinics, particularly in high-demand areas and in regional/remote locations.

| Themes | Subthemes urban | Example quote | Subthemes regional/remote | Example quote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Structural challenges | 1a. Understaffing results in increased strain on existing workforce****** | ‘There is no depth in the medical, nursing and psychology workforce. If clinicians are ill for instance, there is no capacity to absorb the extra appointments’ | 1a. Understaffing results in service not offered or staff performing multiple jobs**** | ‘Staff retention and recruitment are a major challenge as these positions can take years to fill…Since January 2023, this position [community nurse] has been vacant and covered less regularly as a face-to-face service’ | |

| 1b. Financing shortfalls compromise the ability to adequately manage STIs***** | ‘We have outgrown the clinic, but cannot use space better by expanding hours without more admin/nursing positions created’ | 1b. Under-financing hinders continuous professional development and negatively impacts health promotion*** | ‘Staff training availability – no affordable and accessible post graduate certificate or higher courses in sexual health.’ | ||

| 1c. Need to enhance infrastructure to create more room at SHCs or establish new SHCs to meet demand for services*** | ‘This is a large and populated LHD with just one SHC’ | 1c. Shortage of staff housing hinders ability to hire and retain staff | ‘Availability of adequate and safe accommodation is in some locations not readily available as community nurses are not as high priority as the acute staff’ | ||

| 2. Community challenges | 2a. Embracing new modalities of delivery of sexual health services to improve patient access** | ‘Access to primary care testing, health promotion to backpackers and international visitors requires attention’ | 2a. Embracing new modalities of delivery of sexual health services to improve patient access** | ‘A mobile clinic van to take the service to where the people are POCT to be made available to clinics for all STIs and BBVs – test and treat same day instead of having to wait for results.’ | |

| 2b. Clinic needs to cater to culturally and linguistically diverse clients | ‘Access to primary care testing, health promotion to backpackers and international visitors requires attention’ | 2b. Clinic needs to be accessible | ‘Vast distances and transport issues for clients, availability of cars for staff’ | ||

| 2c. Clinics need to cater for changing patient demands* | ‘Escalating PrEP patient cohort and GPs not on board with PrEP provision in our LHD’ | ||||

| 2d. Clinics need to cater for migrants without Medicare | ‘Growing numbers of immigrants without Medicare’ |

LHD, local health district; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; SHC, sexual health clinic; GP, general practitioner; POCT, point of care test; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

*Indicates number of additional participants sharing this sentiment.

Bold text highlights key issue raised.

Most community challenges focused on the need to adopt new approaches to meet the growing demand for SH services. Suggestions were made on how these community challenges can be overcome, and these included integrating primary care providers, such as, general practitioners, into SH testing, using mobile clinics, adapting telehealth models and online STI screening to enhance patient access. Two respondents specifically noted a shift in patient needs, particularly highlighting the increasing demand for HIV PrEP and migrants without Medicare. Additionally, respondents from rural SH clinics stressed the need to enhance accessibility for culturally and linguistically diverse populations, including providing transportation to reduce the costs and other barriers associated with attending clinics.

Discussion

We found that SH clinics in Australia were unable to see all patients with symptoms on the same day on approximately 30% of the days during summer, and approximately 25% of the days during winter. When we adjusted this by the number of consultations that the clinic provided, then for at least half of the time, symptomatic patients were likely to encounter a clinic that may be unable to see them. Inadequate STI services put upward pressure on STI rates, which can create a vicious cycle that leads to further increases in STIs.11 Our findings suggest that clinics currently lack the capacity to adequately meet demand, and with rising STI rates and increasing barriers to accessing primary care, this will only worsen. On a positive note, we identified potential efficiencies within the existing system. For example, clinics could direct resources away from simple screening of asymptomatic individuals and focus on symptomatic individuals who have a higher risk of HIV/STI, and whose treatment is likely to prevent more transmission given they have only recently acquired their infections. The public health consequences of inadequate access to SH care are already evident in some jurisdictions, with rapidly rising rates of syphilis among women and the resurgence of congenital syphilis, which has been virtually absent for decades.1

What matters most for effective STI control and for a person’s individual health is what happens to those most likely to be diagnosed with the infections of greatest health consequences, such as HIV and syphilis. A primary syphilitic chancre will resolve spontaneously without treatment, and despite symptoms resolving, that individual will remain infectious to others and at risk of serious complications themselves. Our study shows that most SH services prioritise patients with symptoms suggestive of high-risk infections, such as syphilis, but little is known about individuals who do not successfully navigate to these services or do not wait to be seen during particularly busy times when wait times can be hours.

We are not aware of what level of service translates into effective STI control, although a system that could always see 100% of symptomatic patients would be expensive. The British Association for Sexual Health and HIV have recommended that all patients with symptoms of an STI should receive care within 48 h, although this recommendation was not based on empirical evidence of what is or is not effective for STI control.12 Additionally, to be confident of accessibility, clinics would need to monitor attendance rates to ensure people offered future appointments do actually access care. Clearly though, the current situation in Australia where on 50% of days clinics cannot see all patients is inadequate. What makes this situation particularly concerning is that sexual practices that put individuals at risk of STIs are rising. For example, the proportion of MSM who always use a condom for anal sex with casual partners has fallen from 47% in 2014 to 16% in 2022.13 These behavioural changes and the rising STI rates highlight how critical it is that access to health care is optimised as soon as possible.

There are no process markers (e.g. percentage of symptomatic individuals seen in <2 h), but it may be possible to imply what countries may have ‘accessible’ STI care by comparing the rates of syphilis in women (and congenital syphilis) between countries of similar economic status. These rates vary markedly. At one end of the spectrum are the Scandinavian countries or the Netherlands (population 17 million) in 2023, where rates are low, whereas at the other end is the US in 2022, where 26% of syphilis cases were in women, and there were 3882 cases of congenital syphilis (rate 105.8 per 100,000). In the Netherlands, only 2% of infectious syphilis cases were in women, and there were no cases of congenital syphilis in 2023. In Australia in 2023, 20% of infectious syphilis was in women (rate 10 per 100,000), and there were 20 cases of congenital syphilis (rate 0.1 per 100,000). These figures suggest Australia’s STI control is poor, and at risk of major rises in congenital syphilis unless services are substantially improved.

Encouragingly, there was scope for improving the efficiency and effectiveness of some of the SH clinics. Our results show that there are nearly four times as many consultations allocated to asymptomatic screening compared with symptomatic cases. Although some of these may be associated with important HIV prevention strategies, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis, many may not be. Given that treatment of symptomatic individuals is likely to have a larger effect on the duration of infection and the overall reproductive rate of an STI than treatment of asymptomatic individuals, prioritising symptomatic cases could be a more efficient strategy for improving the efficiency of the services.5 In addition, the relatively long time (20 min) for screening highlights a substantial resource allocation that could potentially be redirected towards symptomatic individuals. There are web-based services available at low cost or no cost (to individuals) for testing of asymptomatic individuals for STIs, and it may be that those with Medicare or insurance should be directed to such services.14

The other area where services might improve their efficiency is to increase the risk profile of patients that they see. In our study, there was substantial variation between clinics (2–5-fold) in the proportion of consultations with STIs, which suggests that some clinics are not attracting sufficiently high-risk individuals. Relatively simple changes in clinic process, such as moving from an appointment system to a walk-in triage system, can substantially improve the risk profile of the patients seen.15 Making data available on the proportion of consultations positive for different STIs would allow clinics to benchmark themselves against other services.

The key question for governments who have oversight of these clinics is what should be done? We have clearly shown that these services are understaffed and under resourced to meet the current patient demand, although there are some efficiencies that could be implemented. Unfortunately, obtaining more funding for these services is, and is likely to remain, a low priority for governments around the world. This is because this area of medicine is the lowest prestige medical speciality and, like other areas where individuals are seen to be responsible for their own conditions, is politically unpopular.16 General practitioners and their clinic staff play a major role in Australia, but need to be resourced for this role, which has been effectively done for a small number of general practice clinics in Victoria.5 Recent policy changes to improve access to Medicare-funded sexual and reproductive telehealth are likely to improve access to care; however, policy barriers still prevent the cost-effective automated services used extensively in the UK. Medicare-funded urgent care services have the potential to improve timely access to primary care for people with symptoms, but efforts are needed to ensure these services have access to the knowledge and skills to perform this role in a manner that meets the needs of most at-risk populations. However the stigma associated with STIs means there will remain a proportion of individuals who will only attend STI clinics, so adequate resources are required for SH clinics if optimal STI control is desired by governments.

Our study has several limitations that need to be considered. First, our survey relied on the perspectives and opinions of the clinic directors rather than actual data. This reliance on self-reported data may have introduced some biases, such as respondents overstating their difficulties in providing services to justify requests for additional resources. Although we cannot confirm the presence of these biases, our findings are consistent with anecdotal reports that clinics are struggling to adequately manage their current patient load. Second, we only surveyed public SH clinics and not private general practice clinics, which also provide a substantial portion of STI services in Australia. Therefore, we cannot infer that general practice clinics face similar pressures. However, there are reports indicating growing difficulties in accessing general practice services in Australia, which may suggest comparable challenges.9,17

If Australia wants to avoid the devastating effects of relentless rises in STIs and a vicious cycle of rising rates with limited services, then something needs to change to avoid the exponential rises in cases of congenital syphilis currently being seen in some US states (e.g. Mississippi). Access to clinical services is the single strongest STI control strategy, and our data show it is not able to meet demand. Without adequate resources, the escalating burden of STIs is likely to worsen, potentially leading to higher disease burden and health complications that will be eventually more expensive to manage in the long term.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest

JJO is the co-Editor-in-Chief, LZ, DBR, and EPFC are Associate Editors for Sexual Health but were not involved in the peer review or decision-making process for this paper. The authors have no further conflicts of interest to declare.

Declaration of funding

CKF and EPFC are supported by an Australian NHMRC Leadership Investigator Grant (GNT1172900 and GNT2033299, respectively). JJO and EPFC are supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Emerging Leadership Investigator Grant (GNT1193955, GNT1172873 respectively).

Author contributions

CKF conceived the study. CKF, EPFC and RK (acknowledgement) designed the questionnaire. RK sent out the questionnaire, and collated the initial data and provided the first drafts of the paper. CKF progressed and completed the paper, and undertook the final analysis of the quantitative data. TP and RK undertook the analysis of the qualitative data. All authors revised the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final version of the manuscript. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Acknowledgements

We thank the directors of sexual health services for the data they provided. Dr Reuben Kiggundu contributed to the study (see author contributions), but returned to Uganda, and was not able to be contacted and could not approve the final version. We acknowledge his contribution to carrying out the survey and providing early drafts.

References

2 Aung ET, Chen MY, Fairley CK, Higgins N, Williamson DA, Tomnay JE, et al. Spatial and Temporal Epidemiology of Infectious Syphilis in Victoria, Australia, 2015–2018. Sex Transm Dis 2021; 48(12): e178-82.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

3 Melbourne Sexual Health Centre. Your experts in sexual health; 2012. Available at http://www.mshc.org.au [cited 9 October 2012]

4 Walia AM, Fairley CK, Bradshaw CS, Chen MY, Chow EPF. Disparities in characteristics in accessing public Australian sexual health services between Medicare-eligible and Medicare-ineligible men who have sex with men. Aust N Z J Publ Health 2020; 44(5): 363-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

5 Fairley CK, Chow EPF, Simms I, Hocking JS, Ong JJ. Accessible health care is critical to the effective control of sexually transmitted infections. Sex Health 2022; 19(4): 255-64.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

6 Ong JJ, Fairley CK, Fortune R, Bissessor M, Maloney C, Williams H, Castro A, Castro L, Wu J, Lee PS, Chow EPF, Chen MY. Improving access to sexual health services in general practice using a hub-and-spoke model: a mixed-methods evaluation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19(7): 3935.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

7 De Abreu Lourenco R, Kenny P, Haas MR, Hall JP. Factors affecting general practitioner charges and Medicare bulk-billing: results of a survey of Australians. Med J Aust 2015; 202(2): 87-90.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

8 Pak A, Gannon B. Do access, quality and cost of general practice affect emergency department use? Health Policy 2021; 125(4): 504-11.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

9 Branley A. Getting an urgent appointment with your GP or doctor can be hard It’s not meant to be. Australia ABC News; 2023. Available at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-06-21/urgent-gp-appointments-difficult-to-get-in-regional-rural-areas/102496354 [cited 2024]

10 Qualtrics. Qualtrics AI + the XM platform. Available at https://www.qualtrics.com/au/

11 White PJ, Ward H, Cassell JA, Mercer CH, Garnett GP. Vicious and virtuous circles in the dynamics of infectious disease and the provision of health care: gonorrhea in Britain as an example. J Infect Dis 2005; 192(5): 824-36.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

13 Farquharson RM, Fairley CK, Abraham E, Bradshaw CS, Plummer EL, Ong JJ, et al. Time to healthcare seeking following the onset of symptoms among men and women attending a sexual health clinic in Melbourne, Australia. Front Med 2022; 9: 915399.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

14 Cardwell ET, Ludwick T, Fairley CK, Bourne C, Chang S, Hocking JS, et al. Web-based STI/HIV testing services available for access in Australia: systematic search and analysis. J Med Internet Res 2023; 25: e45695.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

15 Tideman RL, Pitts MK, Fairley CK. Effects of a change from an appointment service to a walk-in triage service at a sexual health centre. Int J STD AIDS 2003; 14(12): 793-5.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

16 Norredam M, Album D. Prestige and its significance for medical specialties and diseases. Scand J Public Health 2007; 35(6): 655-61.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

17 McIntyre D, Chow CK. Waiting time as an indicator for health services under strain: a narrative review. Inquiry 2020; 57: 46958020910305.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |