Exploring syphilis activity for personalized treatment strategies in latent syphilis: a 2-year cohort study

Jia-Wen Xie A B # , Ya-Wen Zheng A C # , Shu-Hao Fan A B , Yin-Feng Guo A B , Ying Zheng A B , Yu Lin A B , Man-Li Tong A B and Li-Rong Lin A B *

A B *

A

B

C

# These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Handling Editor: Michael Marks

Abstract

Relying simply on the stage of latent syphilis may lead to excessive treatment strategies. Utilizing nontreponemal immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies to assess syphilis activity and tailor treatment strategies may offer enhanced therapeutic advantages.

To investigate whether nontreponemal IgM antibodies can serve as a serological marker for assessing the activity of latent syphilis and inform personalized treatment strategies.

We evaluated nontreponemal IgM antibodies in 412 latent syphilis patients and conducted a 2-year follow up to analyze their rate of seroconversion (the change from seropositive to seronegative status), to evaluate whether nontreponemal IgM antibodies could assess the activity of latent syphilis.

The positive nontreponemal IgM group demonstrated a lower seroconversion rate (P = 0.0178) and achieved seroconversion slower compared with the negative group (hazard ratio: 0.386). Early-stage patients exhibited higher nontreponemal IgM antibody levels (P < 0.0001) and lower seroconversion rates (P = 0.018) than late-stage patients. Elderly patients showed lower nontreponemal IgM antibody levels (P < 0.0001) and higher seroconversion rates (P = 0.0022) than non-elderly patients.

Latent syphilis patients with positive nontreponemal IgM require a longer time to seroconversion and exhibit a lower seroreversion rate, indicating their higher syphilis activity. Nontreponemal IgM antibodies can serve as a serological marker for detecting syphilis activity in latent syphilis. It is recommended to test for nontreponemal IgM antibodies before treatment to identify syphilis activity for personalized treatment.

Keywords: cohort study, latent syphilis, nontreponemal IgM antibody, serological marker, syphilis, syphilis activity, Treponema pallidum, treatment strategies.

Introduction

Syphilis is an infectious sexually transmitted disease caused by Treponema pallidum.1 This disease is characterized by alternating phases of active clinical infection and periods of latent infection. The latent infection period, referred to as latent syphilis, is defined as seropositivity, but without any clinical symptoms.2,3 Recent years have witnessed a significant and rapid rise in the prevalence of latent syphilis epidemics on a global scale, including America, France, Greece and especially in China.4–8 In 2019, the proportion of latent syphilis cases reached 82.95% in China, a phenomenon likely linked to the widespread implementation of syphilis serological screening within the Chinese healthcare system.9 Although significant progress has been made by the Chinese healthcare system in implementing and strengthening syphilis prevention and control measures, the effective management of latent syphilis patients remains a major public health concern.

Based on the estimated infection duration, latent syphilis is typically divided into two phases: cases with a duration of <1 year are classified as early latent syphilis, whereas those persisting for ≥1 year are termed late latent syphilis.3,10–12 However, it is important to note that global guidelines vary; for example, the UK adopts a 2-year threshold for defining late latent syphilis.2 Owing to the lack of observable clinical manifestations, the therapeutic strategy for latent syphilis is intrinsically dictated by the stage of the disease. The management of late-stage latent syphilis necessitates an extended treatment duration compared with early-stage latent syphilis, as the microbial division rate may be slower theoretically.10,11 Specifically, in early latent syphilis, the timely administration of effective antibiotic regimens is imperative, whereas treatment during the late stage aims to forestall complications in asymptomatic individuals.2,13 However, accurately staging latent syphilis is challenging in practical clinical practice, as there are no clinical symptoms to guide diagnosis. Patients often struggle to accurately determine the precise time of infection, raising the possibility of incorrect disease staging for a significant proportion of latent syphilis cases.

Relying solely on disease staging as the basis for treatment decisions may result in inappropriate antimicrobial use, especially considering the possibility of misclassification of the disease stage. Such approaches might yield negative implications for certain populations, particularly older adults (aged ≥60 years), a group defined in global health studies as experiencing age-related immunosenescence and altered treatment responses.14 This population experiences a higher prevalence and severity of adverse drug reactions, with antibiotics playing a pivotal role.15 In recent years, accumulating evidence from multiple countries has pointed to a significant upsurge in syphilis incidence within the older adult population.16–19 Furthermore, within the older syphilis cases, there has been a marked increase in the diagnosis of latent syphilis.16 Treating latent syphilis requires a more comprehensive approach that considers individual characteristics rather than merely focusing on staging, with the goal of reducing inappropriate antimicrobial use.

Although syphilis is less active during the latent phase, it does not imply the disease is in a quiescent state. Previous studies revealed that up to 25% of latent syphilis patients experience recurring secondary symptoms.3 Additionally, approximately 13.5% of latent syphilis patients exhibit evidence of asymptomatic neurosyphilis.12,20 Opting for treatment strategies based on the activity of latent syphilis could potentially offer a more rational approach, and the application of nontreponemal immunoglobulin (Ig)M antibodies detection might identify latent syphilis activity. In response to T. pallidum infection, the immune system produces nontreponemal antibodies targeting cardiolipin,21,22 with IgM antibodies emerging during early infection and remaining consistent through continuous stimulation by active T. pallidum.23,24

In our previous research, we found that nontreponemal IgM antibodies can be employed as a serological indicator of syphilis activity in serofast patients.25 The purpose of this study is to evaluate whether nontreponemal IgM antibodies could assess the activity of latent syphilis. To achieve this, this study evaluated nontreponemal IgM antibodies in 412 latent syphilis patients and conducted a 2-year follow-up to analyze their rate of seroconversion (the change from seropositive to seronegative status). Additionally, we analyzed nontreponemal IgM antibodies and seroconversion rates in latent syphilis patients across different stages and age groups, aiming to establish the groundwork for personalized treatment for latent syphilis patients.

Materials and methods

Participants and study design

This study was conducted at Zhongshan Hospital, Xiamen University, a tertiary medical center in Xiamen, China. This hospital has been designated as the China Syphilis Research Partnership. The inclusion criteria for this study were patients with latent syphilis, whereas the exclusion criteria were HIV-positive patients and those who declined to participate. Based on the guidelines of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention24 and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control,26 syphilis cases were defined as individuals with positive syphilis serological test results, specifically with both the toluidine red unheated serum test (TRUST) and chemiluminescence immunoassay being positive. Latent syphilis patients were identified as those with positive syphilis serological results, but lacking corresponding clinical symptoms of syphilis. Within this group, those infected for <1 year were categorized as early latent syphilis, whereas those with infections >1 year were classified as late latent syphilis. In this study, the primary dependent variable was the seroconversion rate within 24 months. The primary independent variable was the nontreponemal IgM antibody status (positive or negative) at baseline. Secondary independent variables included syphilis infection duration (early or late) and patient’s age group (≥60 years or <60 years).

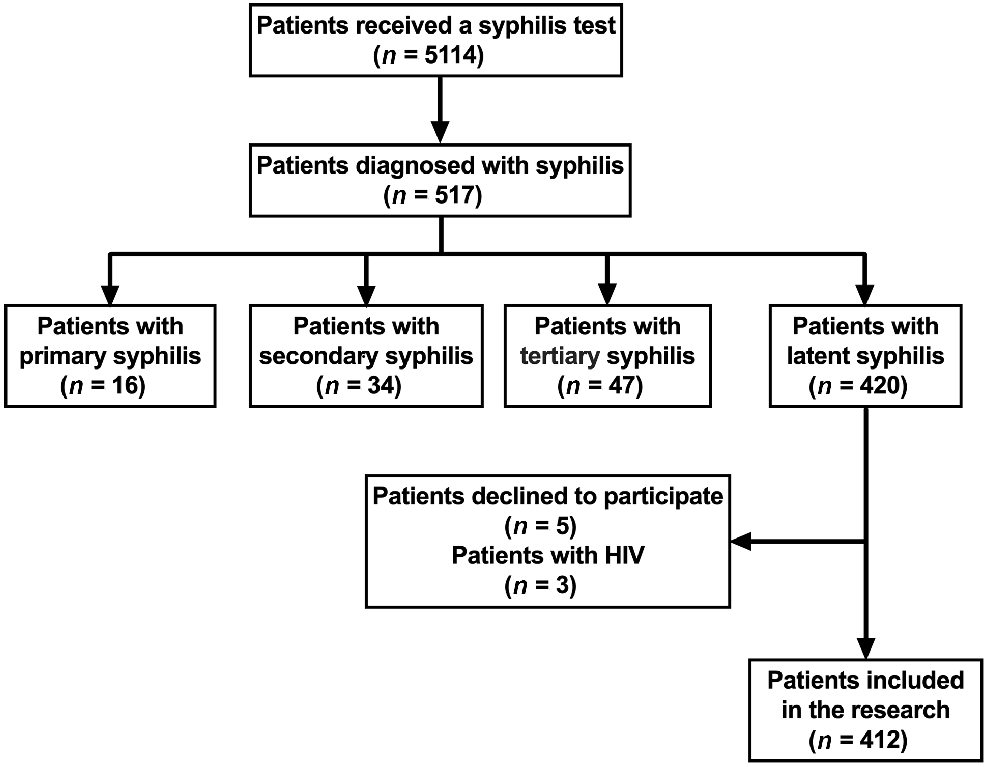

From January 2020 to February 2021, a total of 5114 patients underwent serological testing for syphilis. Among these, 517 individuals were identified as syphilis cases and subsequently treated with penicillin.11 Of these diagnosed cases, 420 (81.24%) were classified as latent syphilis patients. After excluding three HIV-positive patients and five individuals who declined to participate, the final study cohort included 412 latent syphilis patients (Fig. 1).

Serum samples were gathered and preserved at a temperature of −80°C for subsequent testing of nontreponemal IgM antibodies. A total of 126 latent syphilis patients had follow-up data on TRUST titers within 24 months after receiving penicillin treatment, we documented in detail the time it took for TRUST titers to turn negative in these patients and analyzed their seroconversion rate. We used the STROBE cohort checklist when writing our report.27

Nontreponemal IgM antibodies test

Nontreponemal IgM antibody detection involved a two-step indirect immunoassay methodology. A commercially available chemiluminescence test kit from Boson Biotech (Xiamen, China) was employed following the manufacturer’s instructions. Chemiluminescent reaction quantification was performed in relative light units using a BHP9504-02 chemiluminescence device (Hamamatsu Photon Techniques, Hamamatsu, Japan) was utilized. The resulting chemiluminescence signal was compared with the cutoff value, a positive outcome was identified when the cutoff value was ≥1.0, whereas a negative result was determined for a cutoff value <1.0.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was executed through the application SPSS Statistics version 25 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 9.5.0. (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical findings were presented in the form of medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) or numbers and percentages. Categorical variables included nontreponemal IgM antibody status (positive/negative), syphilis infection duration (early/late latent syphilis) and age group (≥60 years/<60 years). Quantitative variables included baseline TRUST titer and time to seroconversion (in months). Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test (or Fisher’s exact test), and quantitative variables were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test. The odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated with the chi-squared test. Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank tests were employed for the time-to-event analysis. All analyses were two-sided, a P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

In compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and national legislation, this research received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital, Xiamen University (No: xmzsyyky2023084). The written informed consent was obtained from the patients in accordance with institutional protocols.

Results

Basic information of the 412 latent syphilis patients

The cohort of 412 latent syphilis patients had a relatively balanced sex distribution, with 48.30% (199/412) identified as male and 51.70% (213/412) as female. Among these patients, 302 individuals were aged <60 years, constituting 73.20% of the entire latent syphilis population (302/412), whereas 110 patients were aged ≥60 years, making up 26.70% of the total cases (110/412). Individuals in the early stage of latent syphilis comprised 60.68% (250/412) of total patients, and those in the late stage accounted for 39.32% (162/412) of the total. Positive nontreponemal IgM antibodies were observed in 20.63% (85/412) of cases, with the remaining 79.37% (327/412) demonstrating negative nontreponemal IgM antibody results (Supplementary Table S1).

Nontreponemal IgM antibodies predicted the seroconversion rate in latent syphilis patients

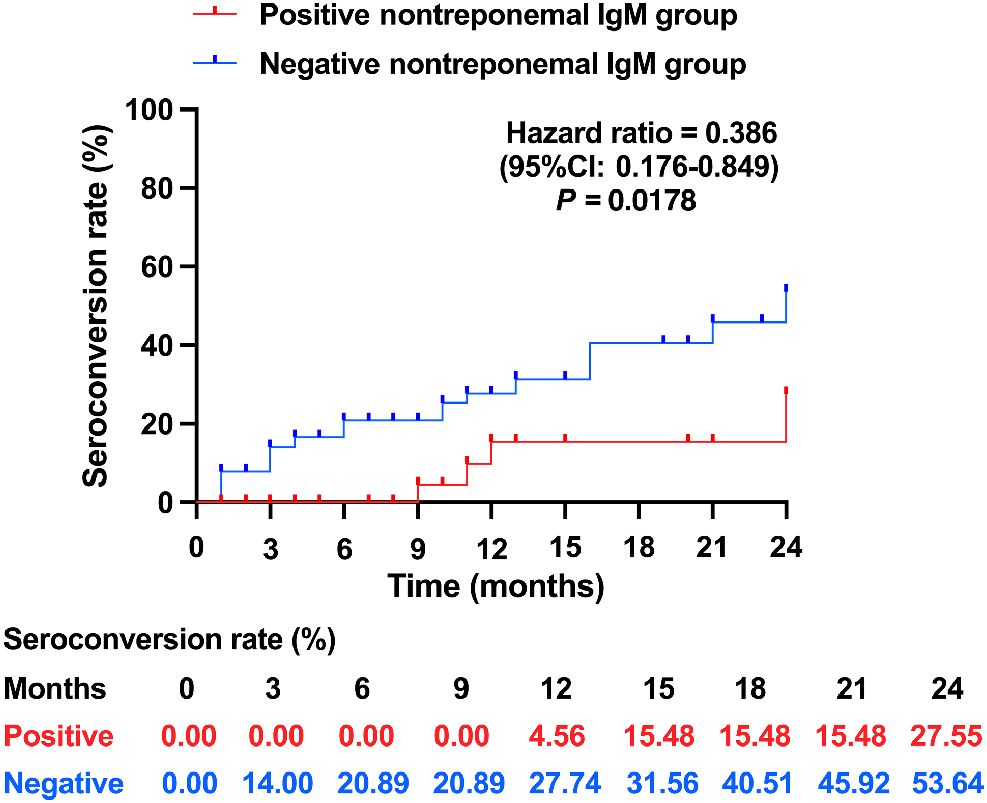

The conversion of TRUST titers from positive to negative, also defined as seronegative conversion, implies the disappearance of syphilis activity.13,28Fig. 2 illustrates that the positive nontreponemal IgM group exhibited a longer time to reach seroconversion and a lower seroconversion rate than the negative nontreponemal IgM group, as evidenced by a hazard ratio of 0.386 (95% CI: 0.176–0.849).

Nontreponemal IgM antibodies in patients with different stages of latent syphilis

Of 250 patients with early latent syphilis, 82 tested positive for nontreponemal IgM antibodies, whereas only 3 of the 162 patients with late latent syphilis showed positive nontreponemal IgM antibodies, suggesting that the positive rate of nontreponemal IgM antibodies testing was considerably higher in early latent syphilis patients than in late latent syphilis patients (32.80% vs 1.85%, P < 0.0001). Positive nontreponemal IgM antibodies were 25.87 times (95% CI: 8.01–83.54) more likely to be detected in patients with early latent syphilis than in those with late latent syphilis (Table 1), which underscores IgM’s potential as a critical serological marker for distinguishing early from late latent stages.

| Nontreponemal IgM antibodies positive rate | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | 32.80% (82/250) | 25.87 (8.01–83.54) | <0.0001 | |

| Late | 1.85% (3/162) | Reference |

The chi-squared test was used to explore the difference in nontreponemal IgM antibodies positive rate between early and late latent syphilis patients, and calculated the odds ratio. The odds ratio was used to determine the probability of nontreponemal IgM antibody positivity in patients with early-stage latent syphilis versus that of late-stage latent syphilis.

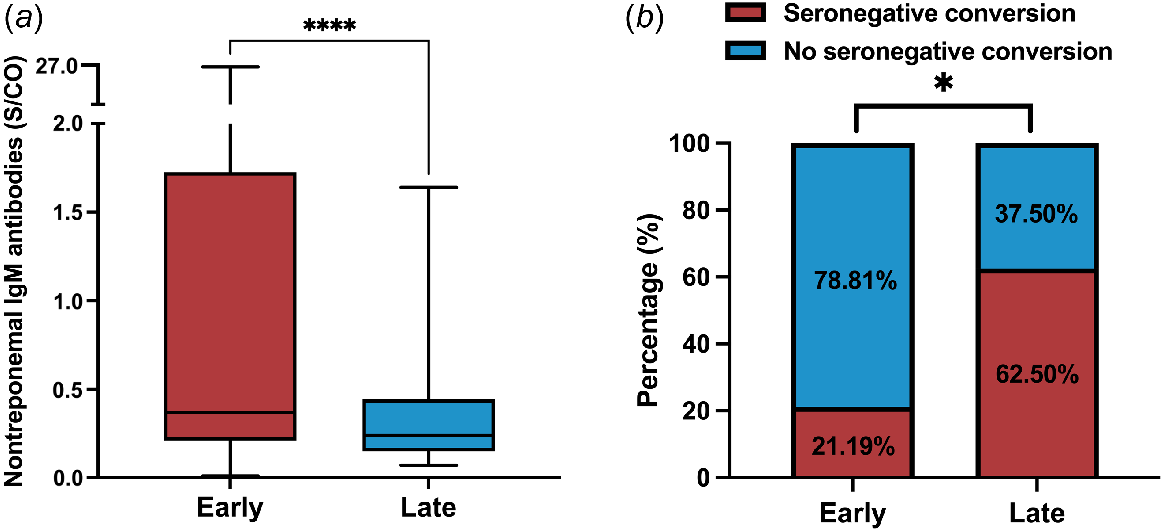

Early latent syphilis patients (median: 0.37; IQR: 0.21–1.72) exhibited significantly higher nontreponemal IgM antibody values than late latent syphilis patients (median: 0.24; IQR: 0.15–0.44; P < 0.0001; Fig. 3a). The seroconversion rate among late latent syphilis patients was found to be 62.50%, with five out of eight patients experiencing seronegative conversion, whereas three did not. In contrast, patients with early latent syphilis exhibited a significantly lower seroconversion rate of 21.19%, with only 25 out of 118 patients experiencing seronegative conversion (P = 0.018; Fig. 3b).

Nontreponemal IgM antibodies in patients with different stages of latent syphilis. (a) Nontreponemal IgM antibody values in patients with different stages of latent syphilis. (b) Seroconversion rate in patients with different stages of latent syphilis. The Mann–Whitney U test and boxplot were used to demonstrate the difference in nontreponemal IgM antibody values between early and late latent syphilis patients. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the seroconversion rates in patients with different stages of latent syphilis.

Nontreponemal IgM antibodies in elderly and non-elderly patients with latent syphilis

Latent syphilis patients were divided into two age groups, namely elderly and non-elderly, with a demarcation threshold of 60 years of age. The results showed that the nontreponemal IgM antibody positive rate was significantly lower in the elderly group than in the non-elderly group (9.09% vs 24.83%, P = 0.0005). The probability of detecting positive nontreponemal IgM antibodies in the elderly group was 0.30 times (95% CI: 0.15–0.60) that of detecting positive nontreponemal IgM antibodies in the non-elderly group (Table S2).

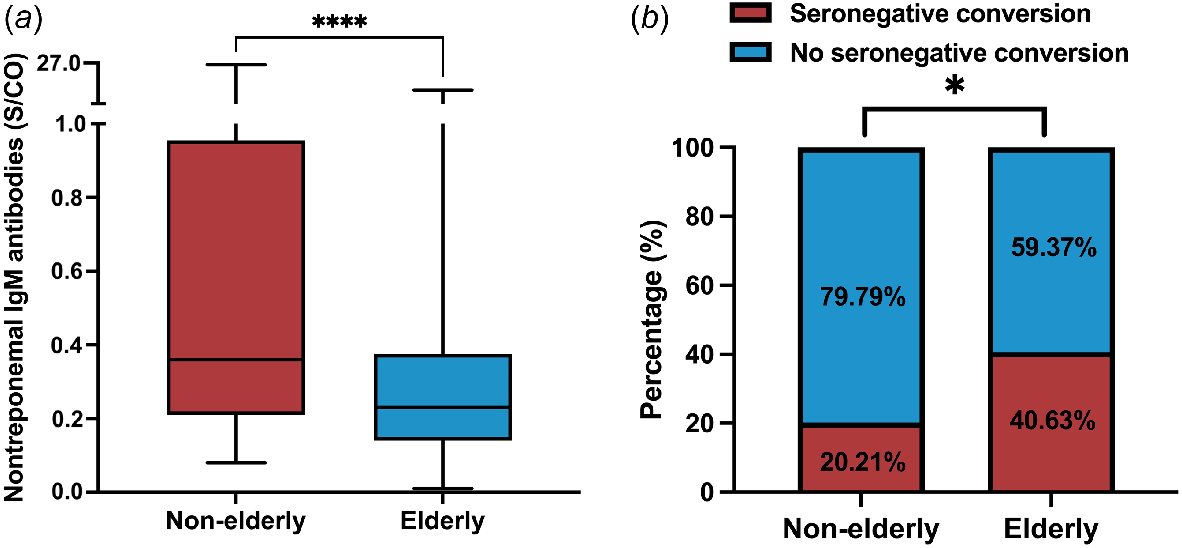

Fig. 4a revealed that the nontreponemal IgM antibody values were also significantly lower in the elderly group than in the non-elderly group (median, IQR: 0.23, 0.14–0.37 vs 0.36, 0.21–0.95; P < 0.0001). In the meantime, seroconversion rates also differed across age groups of patients with latent syphilis, with significantly higher seroconversion rates in the elderly group (P = 0.022) (Fig. 4b). Among the 32 elderly latent syphilis patients, 13 individuals exhibited seronegative conversion following treatment, whereas 19 remained seropositive, yielding a seroconversion rate of 40.63%. Of the 94 non-elderly patients with latent syphilis, 19 achieved seronegative conversion after treatment, whereas 75 did not, resulting in a seroconversion rate of 20.21%.

Nontreponemal IgM antibodies in elderly and non-elderly patients with latent syphilis. (a) Nontreponemal IgM antibody values in elderly and non-elderly patients with latent syphilis. (b) Seroconversion rate in elderly and non-elderly patients with latent syphilis. The Mann–Whitney U test and boxplot were used to demonstrate the difference in nontreponemal IgM antibody values between the elderly groups and the non-elderly groups of latent syphilis patients. The chi-squared test was used to compare the seroconversion rates in elderly groups and the non-elderly groups of latent syphilis patients.

Discussion

The prevalence of latent syphilis has undergone a marked upsurge in recent years. From 2004 to 2019, the proportion of latent syphilis cases within the total syphilis cases in China witnessed a substantial rise, soaring from 20.41% to an astounding 82.95%,9 reflecting that latent syphilis is becoming widespread in the general population. Our investigation also demonstrated that a significant majority of syphilis instances were latent syphilis, making up a substantial 81.24% (420/517) of the total cases. This notable proportion emphasizes the necessity for increased attention toward addressing latent syphilis.

Latent syphilis manifests no symptoms, yet retains its infectivity. Accurate identification of latent syphilis activity is crucial for optimizing its management. Our previous study established that nontreponemal IgM antibodies could act as a reliable serological marker for detecting syphilis activity in serofast patients.25 The current research monitored TRUST titers in patients with latent syphilis over a period of 24 months following treatment, and the findings revealed a diminished seroconversion rate in the positive nontreponemal IgM group compared with the negative IgM antibody group. The hazard ratio further demonstrated a prolonged time to achieve seronegative conversion in the positive nontreponemal IgM group. In other words, positive nontreponemal IgM patients were less likely to attain a serological cure post-treatment than nontreponemal negative IgM antibody patients, which in a way reflected the higher syphilis activity in the positive nontreponemal IgM antibody group.

Currently, the treatment strategies for latent syphilis are contingent upon its stages. Early latent syphilis is typically regarded as infectious and represents active syphilis, whereas individuals in the late stage of latent syphilis are generally considered to pose a lesser risk of sexual transmission,2,3,13,29 consequently, these two stages necessitate distinct treatment strategies. Nonetheless, owing to the lack of discernible symptoms, accurate staging of latent syphilis remains susceptible to errors. Moreover, given the limitations of current treatment methods in fully eradicating syphilis, it emphasizes the critical importance of improving and refining treatment strategies.

In comparison with late latent syphilis patients, early latent syphilis patients showed considerably higher nontreponemal IgM antibody levels and nontreponemal IgM antibody positive rates (median, IQR, positive rate: 0.37, 0.21–1.72, 32.80% vs 0.24, 0.15–0.44, 1.85%). The results of the 2-year follow-up record of patients with latent syphilis provided additional evidence in support of this observation, by demonstrating a lower seroconversion rate in early-stage patients compared with late-stage individuals. Our findings confirm the long-held view that in latent syphilis, the syphilis activity in the early stages is higher than that in the late stages. However, there were patients with low syphilis activity in the early stage and patients with high syphilis activity in the late stage. Exclusively relying on the staging of latent syphilis for treatment decisions could potentially lead to inadequate treatment for patients with high syphilis activity, and unnecessary overtreatment for those with low syphilis activity. A personalized treatment strategy based on the activity of latent syphilis will be the direction of precision treatment for syphilis. However, the implementation of personalized treatment plans required more support from evidence-based medicine.

Infectious diseases are emerging as contributors to the disease burden in older adults, and those aged ≥60 years account for 23% of the total global disease burden.14 Data have shown that older adults (aged ≥60 years) exhibited a remarkably high incidence of latent syphilis.4,5 The alarming growing epidemic of latent syphilis in older adults requires urgent attention. Previous studies have shown that IgM levels in older adults vary depending on the disease. Weymouth et al. found that up to 30% of older individuals tested positive for cytomegalovirus IgM antibodies, compared with only 6% in younger individuals.30 In contrast, Ademokun et al. reported that older adults showed significantly impaired serum IgM responses to pneumococcal vaccination compared with younger adults.31 In this research, we detected lower nontreponemal IgM antibody values and positivity rates in the ≥60-year-old population than in the <60-year-old population, and older adults also showed higher seroconversion rates. It indicated that in the group of patients with latent syphilis, the ≥60-year-old population had lower syphilis activity and better prognosis. Aging triggers inevitable detrimental changes in biological processes, underscoring the paramount importance of drug use in older adult patient care. Inappropriate usage can nullify the therapeutic benefits of drugs, and even escalate the risk of adverse reactions. Striving for therapeutic efficacy while minimizing drug-related toxicity can enhance the overall health of older adult patients, and potentially alleviate some healthcare burdens within society.32,33 Most latent syphilis cases among older adult patients are in the late stage,16 administering prolonged penicillin treatment to them based merely on disease stage might not lead to beneficial outcomes. We recommend that prior to treating patients with latent syphilis, a nontreponemal IgM antibody test should be performed in addition to routine syphilis serology testing to identify the patient’s syphilis activity, thereby providing individualized and precise treatment.

The integration of nontreponemal IgM testing into the diagnostic framework for latent syphilis holds significant promise for refining disease staging and guiding therapeutic decisions. Our findings demonstrate that IgM positivity is strongly associated with early latent syphilis, suggesting its utility as a biomarker of recent or active infection. This is particularly relevant in clinical scenarios where traditional staging criteria, such as patient-reported time since exposure, are unreliable or unavailable. For instance, in patients with ambiguous infection timelines, IgM positivity could support classification as early latent syphilis, thereby aligning treatment with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-recommended single-dose penicillin regimens.24 Conversely, IgM negativity in patients with suspected late latent syphilis (≥1 year post-infection) may help avoid unnecessary overtreatment, reducing antibiotic exposure and mitigating drug supply pressures.34–36 However, we caution against using IgM as a standalone determinant of therapy, rather, it should complement clinical history, serological trends and epidemiological context to achieve personalized staging. Future prospective studies must validate IgM’s prognostic value across diverse populations, including immunocompromised individuals and those with neurosyphilis, to establish standardized protocols for its integration into syphilis management guidelines.

The current study has several limitations. First, due to the inability to determine the expected seroconversion rates for the IgM-positive and IgM-negative groups, the sample size was not pre-calculated. Second, the exclusion of three HIV-positive cases and five patients who declined participation may introduce selection bias, as these groups might exhibit distinct immunological profiles or healthcare-seeking behaviors, potentially underestimating IgM’s diagnostic utility in high-risk populations. Third, incomplete 2-year follow-up records could lead to attrition bias; if patients with treatment failure or relapse were disproportionately lost, our seroreversion rates might be overestimated. Fourth, we lacked continuous monitoring of patients’ nontreponemal IgM antibodies during the follow-up period, so we were unable to track the changes in nontreponemal IgM antibodies. Last, the retrospective design did not systematically document the interval between penicillin treatment and baseline IgM measurement, which prevents definitive conclusions about whether IgM status reflects pre-treatment disease activity or post-treatment immunological changes. It also prevents a meaningful comparison of IgM titers in patients with previously treated syphilis. Future prospective studies should rigorously record treatment timelines to address this limitation.

Conclusion

Above all, our results showed that patients with positive-nontreponemal IgM had a lower seroconversion rate and required a longer duration to attain seronegative conversion than patients with negative-nontreponemal IgM. This observation confirmed that nontreponemal IgM antibody can serve as a serological marker for detecting syphilis activity in latent syphilis. We recommend that patients with latent syphilis be tested for nontreponemal IgM antibodies to identify the patient’s syphilis activity prior to treatment, to provide precise individualized treatment and optimize the clinical management.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers 82371367, 82172331, 82001600, 81871729], the Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 2024D023], and the Fujian provincial health technology project [2024ZD01008]. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

Jia-Wen Xie: methodology, Writing – original draft. Ya-Wen Zheng: formal analysis, investigation. Yin-Feng Guo: software, investigation, Mao Wang: validation, data curation. Yu Lin: supervision, investigation. Man-Li Tong: visualization, investigation. Li-Rong Lin: conceptualization, writing – review and editing. Guarantor is Li-Rong Lin.

References

1 Oumarou Hama H, Boualam MA, Levasseur A, et al. Old world medieval treponema pallidum complex treponematosis: a case report. J Infect Dis 2023; 228(5): 503-510.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

2 Peeling RW, Mabey D, Kamb ML, Chen X-S, Radolf JD, Benzaken AS. Syphilis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017; 3: 17073.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 LaFond RE, Lukehart SA. Biological basis for syphilis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006; 19(1): 29-49.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

4 Wu X, Guan Y, Ye J, et al. Association between syphilis seroprevalence and age among blood donors in Southern China: an observational study from 2014 to 2017. BMJ Open 2019; 9(11): e024393.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

5 Tao Y, Chen MY, Tucker JD, et al. A nationwide spatiotemporal analysis of syphilis over 21 years and implications for prevention and control in China. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 70(1): 136-139.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

6 Fox L, Miller WC, Gesink D, Doherty I, Serre M. Enhancing insights in sexually transmitted infection mapping: syphilis in Forsyth County, North Carolina, a case study. PLoS Comput Biol 2024; 20(10): e1012464.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

7 Kojima N, Klausner JD. An update on the global epidemiology of syphilis. Curr Epidemiol Rep 2018; 5(1): 24-38.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

8 Nanoudis S, Pilalas D, Tziovanaki T, et al. Prevalence and treatment outcomes of syphilis among people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) engaging in high-risk sexual behavior: real world data from Northern Greece, 2019–2022. Microorganisms 2024; 12(7): 1256.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

9 Li J, Yang Y, Huang B, Zeng J. Epidemiological characteristics of syphilis in mainland China, 2004 to 2019. J Int Med Res 2024; 52(6): 03000605241258465.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

10 CDC. Syphilis – STI Treatment Guidelines. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/syphilis.htm [verified March 2023]

11 CDC. Latent Syphilis – STI Treatment Guidelines. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/latent-syphilis.htm [verified March 2023]

12 Brown DL, Frank JE. Diagnosis and management of syphilis. Am Fam Physician 2003; 68(2): 283-290.

| Google Scholar |

13 O’Byrne P, MacPherson P. Syphilis. BMJ 2019; 365: l4159.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

14 Prince MJ, Wu F, Guo Y, et al. The burden of disease in older people and implications for health policy and practice. Lancet 2015; 385(9967): 549-562.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

15 Gavazzi G, Krause K-H. Ageing and infection. Lancet Infect Dis 2002; 2(11): 659-666.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

16 Wang C, Zhao P, Xiong M, et al. New syphilis cases in older adults, 2004–2019: an analysis of surveillance data from south China. Front Med 2021; 8: 781759.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

17 Bodley-Tickell AT, Olowokure B, Bhaduri S, et al. Trends in sexually transmitted infections (other than HIV) in older people: analysis of data from an enhanced surveillance system. Sex Transm Infect 2008; 84(4): 312-317.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

18 Minichiello V, Rahman S, Hawkes G, Pitts M. STI epidemiology in the global older population: emerging challenges. Perspect Publ Health 2012; 132(4): 178-181.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

19 Choe H-S, Lee S-J, Kim CS, Cho Y-H. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections and the sexual behavior of elderly people presenting to health examination centers in Korea. J Infect Chemother 2011; 17(4): 456-461.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

20 Ghanem KG. REVIEW: Neurosyphilis: a historical perspective and review. CNS Neurosci Ther 2010; 16(5): e157-e168.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

21 Gao K, Xu D-M, Lin X-R, Zhu X-Z, Zhang H-L, Tong M-L. Immunization with nontreponemal antigen alters the course of experimental syphilis in the rabbit model. Int Immunopharmacol 2020; 89: 107100.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

22 Rodríguez I, Noda AA, Bosshard PP, Lienhard R. Anti-Treponema pallidum IgA response as a potential diagnostic marker of syphilis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2023; 29(12): 1603.e1-1603.e4.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

23 Seña AC, White BL, Sparling PF. Novel Treponema pallidum serologic tests: a paradigm shift in syphilis screening for the 21st century. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 51(6): 700-708.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

24 Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015; 64(RR-03): 1-137.

| Google Scholar |

25 Zheng Y-W, Chen H, Shen X, Lin Y, Lin L-R. Evaluation of the nontreponemal IgM antibodies in syphilis serofast patients: a new serologic marker for active syphilis. Clin Chim Acta 2021; 523: 196-200.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

26 Janier M, Hegyi V, Dupin N, et al. 2014 European guideline on the management of syphilis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28(12): 1581-1593.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

27 von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007; 335(7624): 806-808.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

28 Luo Z, Ding Y, Yuan J, et al. Predictors of seronegative conversion after centralized management of syphilis patients in Shenzhen, China. Front Publ Health 2021; 9: 755037.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

29 Mattei PL, Beachkofsky TM, Gilson RT, Wisco OJ. Syphilis: a reemerging infection. Am Fam Physician 2012; 86(5): 433-440.

| Google Scholar |

30 Weymouth LA, Gomolin IH, Brennan T, Sirpenski SP, Mayo DR. Cytomegalovirus antibody in the elderly. Intervirol 1990; 31(2–4): 223-229.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

31 Ademokun A, Wu Y-C, Martin V, et al. Vaccination-induced changes in human B-cell repertoire and pneumococcal IgM and IgA antibody at different ages. Aging Cell 2011; 10(6): 922-930.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

32 Borrego F, Gleckman R. Principles of antibiotic prescribing in the elderly. Drugs Aging 1997; 11(1): 7-18.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

33 Beyth RJ, Shorr RI. Epidemiology of adverse drug reactions in the elderly by drug class. Drugs Aging 1999; 14(3): 231-239.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

34 Araujo RS, de Souza ASS, Braga JU. Who was affected by the shortage of penicillin for syphilis in Rio de Janeiro, 2013–2017? Rev Saude Publica 2020; 54: 109.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

35 Pham MD, Wise A, Garcia ML, et al. Improving the coverage and accuracy of syphilis testing: the development of a novel rapid, point-of-care test for confirmatory testing of active syphilis infection and its early evaluation in China and South Africa. EClinicalMedicine 2020; 24: 100440.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

36 Nelson R. Syphilis rates soar in the USA amid penicillin shortage. Lancet 2023; 402(10401): 515.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |