A scoping review of parent-based barriers to parent–child communication about sexuality

Neelam Punjani A * , Shannon D. Scott

A * , Shannon D. Scott  A , Amber Hussain A , Tammy Lu B , Farah Bandali B , Sheila McDonald B , Lisa Allen Scott B , Sonia Sultan C and Megan Kennedy A

A , Amber Hussain A , Tammy Lu B , Farah Bandali B , Sheila McDonald B , Lisa Allen Scott B , Sonia Sultan C and Megan Kennedy A

A

B

C

Abstract

Parent–child communication about sexuality plays a critical role in promoting adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health, yet such discussions are limited across diverse cultural contexts. Despite the importance of comprehensive sexuality, parents frequently face barriers that hinder open and accurate dialogue. This scoping review aims to map the literature on parent-based barriers to sexuality communication with children and youth. It seeks to identify the barriers parents encounter and the socio-cultural dynamics that influence these interactions globally.

Following the Joanna Briggs Institute framework and PRISMA-ScR guidelines, a comprehensive literature search was conducted across 8 databases, yielding 59 peer-reviewed studies from 2000 to 2024. Eligible studies explored parent–child communication on sexuality, focused on barriers and employed qualitative, quantitative or mixed-methods designs.

Six key themes emerged as barriers: (1) parental discomfort and lack of confidence; (2) limited knowledge and educational gaps; (3) restrictive cultural and religious norms; (4) gendered expectations and communication disparities; (5) heteronormative assumptions excluding Two-Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning, Intersex, Asexual (or Ally), plus other sexual and gender identities (2SLGBTQIA+) youth; and (6) concerns about judgment or misinterpretation. These barriers often stem from intergenerational silence, lack of training and societal stigma. Parents of children with disabilities or those identifying as gender-diverse faced additional challenges requiring tailored resources and clinical support.

Effective sexuality requires proactive, inclusive and culturally grounded parental engagement. Addressing structural and emotional barriers through tailored interventions, healthcare collaboration and educational toolkits is essential. This review underscores the need for future research, policy and health promotion efforts to support parent-based sexuality communication, especially for marginalized and under-resourced caregivers.

Keywords: barriers, communication, home-based, parent-child, scoping review, sexual health, sexuality, youth.

Introduction

Sexual health is a vital component of overall well-being, encompassing physical, emotional, mental and social dimensions of human sexuality.1 According to the World Health Organization, every individual has the right to pursue safe and pleasurable sexual experiences free from discrimination, coercion and violence. Sexual health is not limited to biological aspects, but extends to the capacity for informed, respectful and consensual relationships.

A key determinant of sexual health outcomes is access to comprehensive sexuality, which ideally begins early in life and continues across developmental stages.2 This education goes beyond anatomy, disease prevention and pregnancy considerations to include values, intimacy, gender identity and communication skills.3 Global frameworks, such as those established by UNESCO and the United Nations, view sexuality as a human right that supports the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly those related to education, health and gender equity.4,5

Despite this, many adolescents report insufficient exposure to sexuality, particularly in low-resource or socially conservative regions. In the Asia–Pacific region, fewer than one-third of students feel adequately informed (p. 3).5 Furthermore, global health trends – such as rising rates of STIs, earlier sexual initiation and low condom use – underscore the urgency for better education.6,7 Survivors of adverse childhood experiences, including sexual abuse, face long-term health consequences, reinforcing the need for early, protective dialogue.8

Sexuality also plays a pivotal role in reducing gender-based violence and dismantling harmful gender norms. Research shows that rigid beliefs about masculinity are linked to sexual violence perpetration.9 Moreover, individuals who identify as sexually diverse often face disproportionate violence, stigma and barriers to accessing health care.9,10 However, existing curricula often center heteronormative perspectives and miss broader topics, such as love, pleasure, consent or Two-Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning, Intersex, Asexual (or Ally), plus other sexual and gender identities (2SLGBTQIA+) experiences.5,11

Although schools are a key site of formal sexual education, parents are often the primary source of values-based and relational sexual guidance. This review specifically explores barriers parents face in this critical role of communicating about sexuality with their children. Although formal sexuality may occur in institutional settings, this review focuses on general communication that occurs within families, which reflects relational and context-specific exchanges. Parents are uniquely positioned to engage in sexuality-related conversations with their children, particularly through informal, spontaneous and culturally relevant parent–child communication. Positive parent–child communication has been associated with delayed sexual initiation, increased contraceptive use and improved negotiation skills in relationships.12,13

Despite these benefits, many children and young people report limited or absent conversations with their parents about sex and sexuality.14−16 To better understand and address this gap, this scoping review identifies key barriers parents and children face when communicating about sexuality. By mapping findings across diverse settings and populations, this review offers evidence-based insights to inform family-centered interventions, culturally grounded policy and inclusive sexuality strategies.

Methods

Study design

This scoping review was conducted following the methodological framework outlined by the Joanna Briggs Institute for scoping reviews.17 The objective was to systematically map the barriers to parent–child communication about sexuality, and identify gaps in the existing literature. The review adhered to the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines to ensure methodological rigor. This review protocol is available on the Open Science Framework: doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/QSH5V.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria for this review consisted of studies that examined parent–child communication about sexuality, research specifically focused on barriers to effective sexual health discussions and peer-reviewed empirical studies employing qualitative, quantitative or mixed-methods designs, and published from 2000 to 2024. Studies were excluded if they did not address parent–child sexual health communication, were categorized as editorials, opinion pieces or conference abstracts, or if they focused solely on school-based sexuality without parental involvement.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was developed by two health science librarians, incorporating both natural language keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) to maximize retrieval of relevant studies. The search was executed between 6 and 12 October 2022, and updated in October 2024, in the following electronic databases: MedLine, EMBASE, PsycINFO, HealthSTAR via OVID; CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Education Research Complete via EBSCOhost; Scopus and the Cochrane Library via Wiley.

Search terms were adapted for each database and included a combination of MeSH terms, such as: ‘Parents’ OR ‘Caregivers’; ‘Sexuality’ OR ‘Sexual Health Literacy’;” Adolescents” OR ‘Young Adults’ OR ‘Children’; ‘Barriers to Communication’ OR ‘Parent–Child Communication’. Boolean operators, truncation and phrase searching techniques were applied to enhance sensitivity and specificity (full search strategy available in Supplementary material file S1). The search was not restricted by language to maximize inclusion.

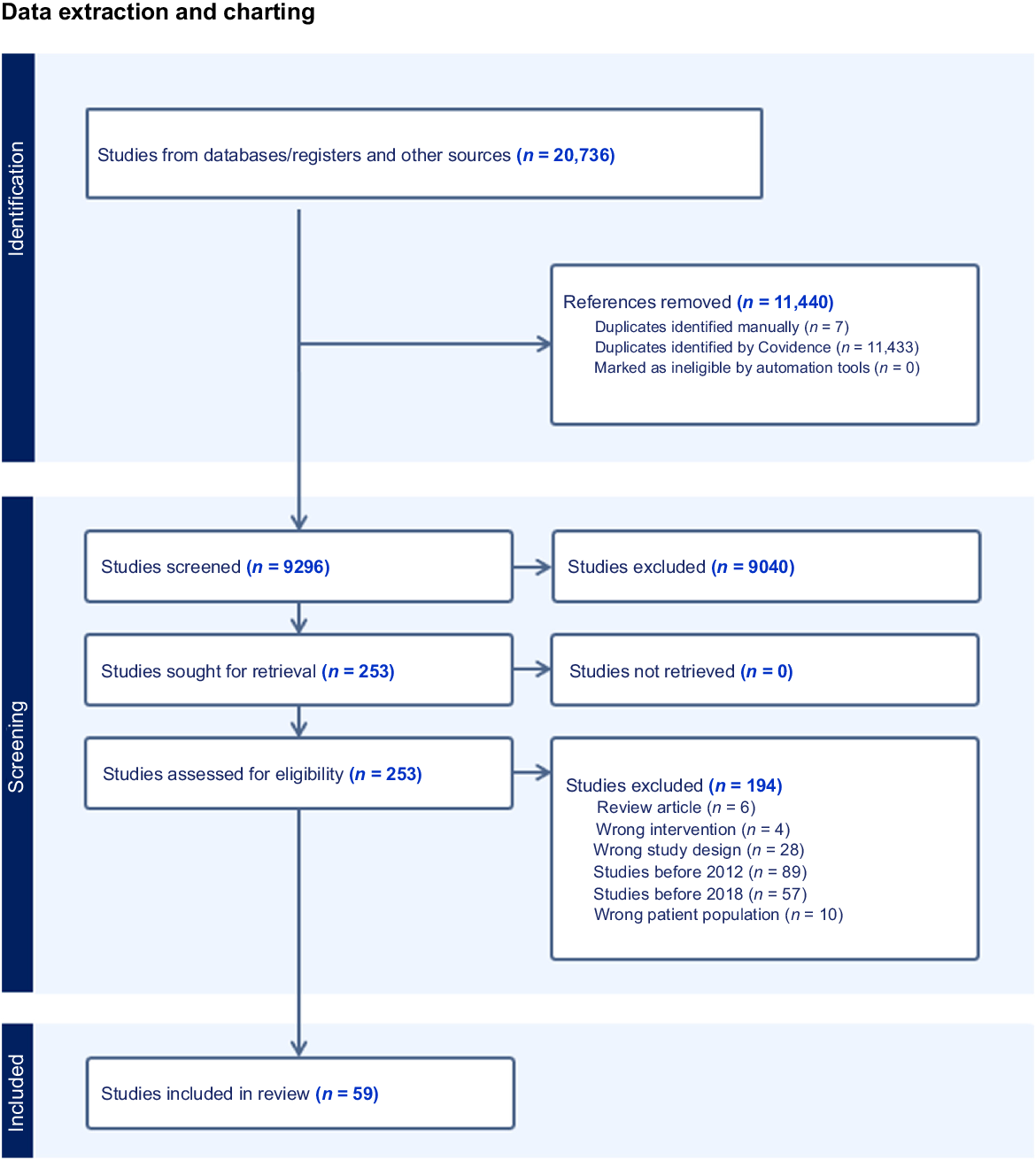

Screening and study selection

Search results were imported into Covidence software for duplicate removal and screening. Of the 20,736 records retrieved, 11,440 duplicates were removed, leaving 9296 unique results for title and abstract screening. Two independent reviewers (RB and SS) screened all studies against predefined eligibility criteria, with discrepancies resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (NP). The final review included 59 studies in total (refer to Fig. 1).

Data extraction and charting

A data extraction template was developed following Joanna Briggs Institute guidelines to systematically collect key study details. Extracted variables included publication year, design, sample size, setting and findings (refer to Supplementary material Table S1). Two independent reviewers conducted data extraction, with discrepancies resolved through consensus.

Data synthesis

Findings were synthesized using a combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches. A narrative synthesis was used to interpret qualitative themes emerging from the literature, and descriptive statistics summarized study characteristics.17 Themes were analyzed using thematic analysis methods to identify recurring patterns regarding barriers in parent–youth sexuality communication. Thematic analysis was used to categorize and synthesize the different types of barriers to parent–child communication about sexuality reported across studies.

Results

Study characteristics

A total of 59 studies met the inclusion criteria, with sample sizes ranging from 8 to 8046 participants. The research encompassed diverse perspectives, including those of children and youth (aged 9–20 years), with sample sizes ranging from 15 to 1700, providing insight into their experiences of communicating with parents about sexuality. Additionally, between 4 and 8046 parents or caregivers shared their experiences of discussing sexuality with their children.

The studies represented a wide geographical range, spanning the USA (n = 23), Panama (n = 1), Italy (n = 1), Nigeria (n = 2), South Africa (n = 4), Ethiopia (n = 4), Australia (n = 3), Austria (n = 1), China (n = 1), Pakistan (n = 1), Jordan (n = 2), Netherlands (n = 1), Colombia (n = 1), Vietnam (n = 1), Thailand (n = 2), Uganda (n = 2), the UK (n = 1), Indonesia (n = 2), Israel (n = 1), Iran (n = 2), India (n = 1) and Lithuania (n = 1).

Most studies utilized qualitative methodologies (n = 37), 21 studies used quantitative approaches and one was a mixed-methods study.

Several recurring themes emerged as barriers to sexuality, including parental discomfort and lack of confidence, limited knowledge and educational gaps, cultural and social norms restricting open discussions, gendered expectations influencing communication, heteronormativity in sex education for 2SLGBTQIA+ youth, and concerns about judgment and safety when discussing sex-related topics. These factors collectively shape the challenges parents and youth face in fostering open and informed conversations about sexuality.

A total of 20 studies reported that parents often experienced discomfort, shame or lack of confidence when discussing sexuality with their children.15,18−36 This discomfort was commonly linked to cultural norms, stigma and a lack of prior modeling from their own upbringing. For example, fathers particularly reported challenges in initiating conversations around sexual health.18,26 In Lithuania, even among mothers who claimed openness, many still experienced residual shame.36

This discomfort was often rooted in intergenerational silence, where parents themselves were raised in environments that discouraged open dialogue.18,33,34 This lack of communication led to emotional unease in approaching sexuality topics with their own children. Parental discomfort was also linked to modern challenges, such as the influence of pornography and new media.20,37 Parents expressed unease with discussing issues arising from adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit content online, fearing that they lacked the appropriate language, knowledge or moral authority to address these topics.37 The ubiquity of Internet access meant that children often encountered graphic material before parents had initiated any conversations, which created anxiety about timing and content. Additionally, some caregivers viewed new media, including social media platforms and messaging apps, as spaces that encouraged risky behavior, eroded family values or promoted misinformation about sex and relationships.20,28 This further compounded their reluctance to initiate dialogue.

Despite this, some parents showed a willingness to improve communication through structured interventions, although concerns about external judgment and adolescents’ discomfort hindered these efforts.15,25,35

A total of 22 studies addressed the role of inadequate parental knowledge and educational preparedness in hindering effective sexuality communication.15,18,20,24,26,34,35,38−52

This educational gap was compounded by deep-seated feelings of embarrassment, fear of promoting early sexual activity and beliefs that discussing sex would conflict with moral or religious values.24,52 In rural or low-income communities, such as in Ethiopia and South Africa, parents often deferred responsibility to schools or healthcare professionals, citing their own lack of preparedness and feeling unqualified to discuss some topics, such as contraception, STI prevention or consent.42,46 Many parents, particularly fathers, expressed uncertainty about appropriate content and the right timing to initiate such discussions, often leading to avoidance or vague messaging.39,41

Notably, studies in both high- and low-income countries indicated that parental education and socioeconomic status were positively correlated with the frequency and quality of communication on sexual and reproductive health issues.38,40 Parents with higher levels of formal education were more likely to feel equipped to handle sexuality discussions, whereas others expressed a desire for training, structured interventions or support materials to guide conversations with their children.15,35

Special populations, such as parents of children with chronic or complex medical conditions, further highlighted these knowledge gaps, and expressed a strong reliance on pediatric specialists for sexual and reproductive health education.39

A total of 24 studies explored the impact of cultural taboos and socioreligious norms in limiting open dialogue about sexuality.14−16,29,34,35,39,44,49,53−66

In many African, Asian and Middle Eastern contexts, sexuality remains a taboo subject, with discussions either delayed until marriage or avoided altogether. For example, parents from Jordan, Pakistan and Arab American backgrounds commonly postponed discussions of sexual and reproductive health due to perceived religious or moral conflicts.53,59,60 Similarly, African immigrant mothers in the US and Indigenous communities in Panama upheld traditions that overemphasized abstinence while avoiding contraception or STI topics.54,56

Religious ideology was a recurring barrier. In Iran and Pakistan, Islamic teachings were often interpreted as conflicting with comprehensive sex education, leading to parent resistance and discomfort.59,62 Christian and Confucian values also shaped silence around sexuality in families from Colombia, India and China.34,44,58

The enduring impact of colonization was particularly evident among Indigenous Australian caregivers, who reported that traditional systems of sexual education had been systematically dismantled, replaced by silence and stigma.66 In contrast, in Latin American and Southeast Asian households, restricted communication was more clearly shaped by entrenched cultural values and family structures, where discussions were often limited to reproduction, and excluded topics, such as STIs, sexual diversity or pleasure.44,49

Interestingly, even in more secular or progressive environments, such as Austria or Australia, parents preferred that schools take the lead in delivering sex education, reflecting lingering discomfort and social expectations.55,65 In these settings, parents acknowledged the importance of sexuality, but remained hesitant to address it in detail at home.35,57

A total of 11 studies addressed how gender roles and expectations shaped the content and style of parent–child sex communication.19,30,37,38,51,52,67−71

Parents communicated differently based on the gender of both parent and child. Fathers were less likely to engage in detailed or open conversations, especially with daughters.68,70,71 Conversations between mothers and daughters emphasized abstinence, modesty or warnings against sexual activity, while neglecting broader aspects, such as consent, pleasure or contraception.19,52,69

Gender also shaped the frequency and quality of communication received by adolescents. Boys were often more likely to receive direct information about sexual behavior or risk prevention, whereas girls received more restrictive and moralistic messages.38,51 In few studies, youth reported reaching out selectively to the parent they believed would be more understanding, often choosing mothers, which further entrenched the gendered dynamic.37,67

Four studies focused on the experiences of 2SLGBTQIA+ youth in the context of heteronormative sexuality.22,64,72,73 Sex education within families was often shaped by heteronormative assumptions. Before coming out, youth received general or risk-based messages rooted in heterosexual norms. After disclosure, discussions were often reactive and informed by misinformation or stigma.

These studies emphasized that sex education was often delivered within a heteronormative framework, with content tailored to cisgender and heterosexual norms. For example, before disclosing their sexual identity, GBQ youth reported that conversations with parents reinforced traditional gender roles.22 Even after disclosure, sex education remained stereotypical and insufficiently inclusive of their needs.22,64

Youth frequently described feeling unsupported, dismissed or judged by their parents when discussing sexuality.22 Mothers, despite good intentions, were often unprepared to deliver inclusive sex education.64 As a result, 2SLGBTQIA+ adolescents turned to peers, media or school-based programs to fill the knowledge gaps left by their families.73

Moreover, some youths were the ones initiating these conversations in an effort to gauge acceptance or seek validation. However, the emotional tone of these exchanges was frequently negative, with feelings of embarrassment, shame or isolation dominating their reflections.72

Discussion

This scoping review synthesized evidence from diverse cultural and geographical contexts to identify key barriers parents and youth encounter when educating and communicating with their children about sex and sexuality. The findings highlight several overlapping themes: discomfort and lack of confidence, limited knowledge, difficulties tailoring age-appropriate conversations, strong cultural and gendered norms, and heteronormative assumptions that particularly affect 2SLGBTQIA+ youth. These barriers are deeply embedded in societal beliefs, family structures and intergenerational dynamics, and were observed across low-, middle- and high-income settings.18,19,24,26,27,29−31,34,36,41,46,52 Notably, young children, especially those identifying as 2SLGBTQIA+, often described their caregivers as unsafe or judgmental, leading to disengagement and silence.19,37 This aligns with broader literature showing that across low-, middle- and high-income countries, regardless of geographic region, parent–child communication is hampered by cultural silence and discomfort, especially around topics perceived as morally sensitive.74−76

The topic of sexuality remains a taboo in many households, often associated with fears of damaging a child’s innocence or promoting early sexual behavior.30,77 Religious and cultural beliefs reinforced these fears, particularly in conservative communities.14,53 This belief was echoed in literature, where parents linked sexuality to fear of moral corruption or loss of purity.76,78 Parents typically delayed conversations until adolescence or post-initiation of sexual activity, often reacting rather than educating proactively.63,71 Girls were more likely to receive abstinence-focused messages, whereas boys encountered vague or permissive instruction,30,69 reinforcing patriarchal norms.69

Parental discomfort was closely linked to intergenerational silence. Many parents had never received sexuality themselves and lacked role models for how to initiate such conversations.18,34 This was compounded by fear of judgment from extended family, religious communities or peers.15,25 Although some parents expressed willingness to engage in interventions, emotional discomfort and lack of preparedness remained major obstacles.

Parents often lacked knowledge about contemporary sexual health topics, including consent, pornography, 2SLGBTQIA++ inclusion and age-appropriate dialogue.20,26,52 These knowledge gaps were validated across various regions, where parents requested structured and evidence-informed sexuality materials.79,80 Educational background, personal experience and cultural exposure all influenced their ability to educate their children. Third-generation caregivers, kinship caregivers and foster parents faced additional hurdles due to limited training.50,51 Parents of children with disabilities or unique health needs required support from healthcare professionals and expressed a need for more tailored resources.39,81 This finding is mirrored in recent reviews showing parents of neurodiverse youth face unique difficulties and often avoid these conversations altogether.82

Modernization and globalization have further complicated sexuality. Digital access, shifting norms and increased visibility of diverse identities mean that parents are expected to address more complex issues than in the past. However, the frequency and quality of conversations remain low and static over time.28,33 Many parents and caregivers, even those willing to communicate, lacked tools to adapt their messaging as children matured.45 Consistent with these findings, global review show that evolving youth exposure to online sexual content and gender diversity requires updated parenting strategies, which many parents lack).83,84 At the same time, digital access offers significant benefits, particularly for 2SLGBTQIA+ youth, by providing accurate, affirming and age-appropriate information via online platforms. These resources are crucial for those who feel silenced or invalidated at home.22,73 There are also growing numbers of websites and tools to support parents in facilitating developmentally appropriate conversations.35 Schools, too, can play a vital role in normalizing discussions around sexual health and gender diversity, providing inclusive, structured environments when home support is lacking.85,86

For 2SLGBTQIA+ youth, the barriers were especially profound. Parental communication often remained heteronormative, even after youth disclosed their identities, leaving them feeling misunderstood, dismissed or emotionally unsafe.22,64 These youth frequently turned to peers, Internet resources or healthcare providers instead. Parents, in turn, expressed a lack of knowledge and discomfort in addressing non-heterosexual identities. This highlights the need for inclusive, affirming and identity-sensitive resources for families. Integrated reviews highlight similar patterns among Western and non-Western families, with 2SLGBTQIA++ youth often reporting that parents either avoided relevant topics or perpetuated stigmatizing attitudes.85 To address the tension between cultural or religious beliefs and inclusive sexuality education, a values-based approach is recommended, one that respects family belief systems while also promoting core human rights principles. Faith-informed dialogue tools, interfaith educator networks, and partnerships with community and religious leaders have shown promise in building culturally respectful entry points for inclusive education.14,53

Given these multifaceted barriers, there is a clear need for comprehensive, culturally grounded and developmentally appropriate resources to support parents in sexuality. These should include strategies to foster confidence, normalize conversations and ensure inclusivity – particularly for marginalized and gender-diverse youth. Based on the findings of this scoping review, several recommendations are proposed to strengthen parent–child communication about sexuality across diverse cultural, social and developmental contexts.

Develop and implement culturally tailored and age-appropriate sexuality toolkits for parents. Public health agencies, education ministries, community-based organizations and parent advisory groups should collaborate in the development and implementation of these resources. Toolkits should be adapted to reflect local cultural norms, family values and language needs. These materials must include specific conversation prompts, myth-busting content and examples relevant to parents from different ethnic, religious and socioeconomic backgrounds to reduce discomfort and misinformation.

Increase the involvement of fathers and male parents through targeted interventions. Given the underrepresentation and reported discomfort of male parents, health and education programs should provide father-specific resources and engagement strategies. These may include workshops, informational materials or peer-led sessions. These interventions should focus on practical guidance for discussing condoms, consent and emotional aspects of sexuality, especially with sons.

Provide sexuality-related support to parents of children with disabilities or complex medical needs. Parents of children with disabilities often seek support from clinical professionals. Health systems should formally incorporate sexuality communication as part of developmental or pediatric care, offering tailored training to support parents in these sensitive discussions.

Promote inclusive sexuality that affirms 2SLGBTQIA+ youth within family settings. Parent-focused sexuality must explicitly address gender identity, sexual orientation and diverse family structures. This includes developing parent-facing modules that guide parents and caregivers in creating safe, judgment-free spaces, and correcting heteronormative messaging.

Encourage early and ongoing parent–youth conversations across developmental stages.

Instead of a single ‘sex talk’, parents should be supported in engaging their children in age-appropriate, progressive discussions about sex, relationships and gender from early childhood through adolescence. This requires developmentally staged resources and school-supported communication guidance.

Limitations

There are a few limitations that should be acknowledged. First, although the search strategy was comprehensive, the review relied solely on peer-reviewed literature and excluded gray literature, dissertations and conference proceedings. This may have resulted in the omission of relevant community-based reports, program evaluations and unpublished studies that could offer valuable insights into practical barriers and real-world parent-youth sexuality initiatives. Second, the review excluded studies that addressed school-based sexuality without a parental component. Although this was appropriate for focusing the scope, it may have missed data on school–home communication dynamics, which are important when examining how parents engage (or disengage) with institutional sexuality programs. Third, the studies included spanned a broad time frame (2000–2024). This temporal range captures evolving cultural and technological influences on sexuality, but it also introduces variability in social norms, educational policies and parental roles that may affect comparability across studies.

Conclusion

This scoping review highlights the pervasive and multifaceted barriers that hinder effective parent–child communication about sexuality across global contexts. Parents, particularly fathers and those caring for 2SLGBTQIA+ or disabled youth, frequently struggle with discomfort, limited knowledge and sociocultural norms that stigmatize open discussions. These challenges are deeply rooted in intergenerational silence, heteronormativity, and insufficient access to developmentally appropriate and inclusive resources. Addressing these gaps requires the implementation of culturally responsive toolkits, father-focused outreach, healthcare integration for special needs families and education for diverse identities. Equally essential is the promotion of early and sustained conversations that evolve with the child’s development. Policymakers and health care providers must prioritize parent support through inclusive national strategies, whereas researchers should expand evidence on context-specific, scalable interventions. Strengthening the capacity of caregivers to deliver informed, inclusive and confident sexuality education is critical to advancing youth health, equity and agency.

Data availability

All data extracted and analyzed during this scoping review are available in the appendices. The sources of all included studies are cited in the reference list.

References

1 WHO. Sexual and reproductive health and research; 2025. Available at https://www.who.int/teams/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-research/key-areas-of-work/sexual-health/defining-sexual-health [Retrieved 22 November]

2 Michielsen K, Ivanova O. Comprehensive sexuality: why is it important? 2022. Available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2022/719998/IPOL_STU(2022)719998_EN.pdf

3 Breuner CC, Mattson G, Committee on Adolescence, et al. Sexuality education for children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2016; 138(2): e20161348.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

4 Mijatović D. Comprehensive sexuality education protects children and helps build a safer, inclusive society; 2020. Available at https://www.coe.int/ca/web/commissioner/-/comprehensive-sexuality-education-protects-children-and-helps-build-a-safer-inclusive-society [Retrieved 23 November]

5 UNESCO, United Nations Children’s Fund, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, United Nations Population Fund, World Health Organization, United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empower of Women. Comprehensive sexuality education: advancing human rights, gender equality and improved sexual and reproduction health; 2021. Available at https://doi.org/10.54675/NFEK1277

6 CDC. Youth risk behavior survey: data sumary and trends report: 2007-2017; 2017. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trendsreport.pdf

7 WHO. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs); 2025. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis) [Retrieved 2023]

8 Campbell JA, Walker RJ, Egede LE. Associations between adverse childhood experiences, high-risk behaviors, and morbidity in adulthood. Am J Prev Med 2016; 50(3): 344-352.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

9 OECD. Love & let live; 2020. Available at https://doi.org/10.1787/862636ab-en

10 Babel RA, Wang P, Alessi EJ, Raymond HF, Wei C. Stigma, HIV risk, and access to HIV prevention and treatment services among men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States: a scoping review. AIDS Behav 2021; 25(11): 3574-3604.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

11 O’Farrell M, Corcoran P, Davoren MP. Examining LGBTI+ inclusive sexual health education from the perspective of both youth and facilitators: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2021; 11(9): e047856.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

12 Saskatchewan Prevention Institute. Parents as sexual health educations for their children: a literature review; 2017. Available at https://skprevention.ca/resource-catalogue/sexual-health/parents-as-sexual-health-educators/

13 Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Noar SM, Nesi J, Garrett K. Parent-adolescent sexual communication and adolescent safer sex behavior: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2016; 170(1): 52-61.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

14 Esan DT, Bayajidda KK. The perception of parents of high school students about adolescent sexual and reproductive needs in Nigeria: a qualitative study. Public Health Pract 2021; 2: 100080.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

15 Ja NM, Tiffany JS. The challenges of becoming better sex educators for young people and the resources needed to get there: findings from focus groups with economically disadvantaged ethnic/racial minority parents. Health Educ Res 2018; 33(5): 402-415.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

16 Morrison-Beedy D, Ewart A, Ross S, Wegener R, Spitz A. Protecting their daughters with knowledge: understanding refugee parental consent for a U.S.-based teen sexual health program. Am J Sex Educ 2022; 17(4): 474-489.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

17 Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. JBI Evid Implement 2015; 13(3): 141-146.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

18 Bennett C, Harden J. Sexuality as taboo: using interpretative phenomenological analysis and a Foucauldian lens to explore fathers’ practices in talking to their children about puberty, relationships and reproduction. J Res Nurs 2019; 24(1-2): 22-33.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

19 Bui TH. ‘Being a good girl’: mother-daughter sexual communication in contemporary Vietnam. Cult Health Sex 2020; 22(7): 794-807.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

20 Davis AC, Wright C, Curtis M, Hellard ME, Lim MSC, Temple-Smith MJ. ‘Not my child’: parenting, pornography, and views on education. J Fam Stud 2021; 27(4): 573-588.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

21 Edwards LL, Hunt A, Cope-Barnes D, Hensel DJ, Ott MA. Parent-child sexual communication among middle school youth. J Pediatr 2018; 199: 260-262.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

22 Flores D, Docherty SL, Relf MV, McKinney RE, Barroso JV. “It’s almost like gay sex doesn’t exist”: parent-child sex communication according to gay, bisexual, and queer male adolescents. J Adolesc Res 2019; 34(5): 528-562.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

23 Gabbidon K, Shaw-Ridley M. Characterizing sexual health conversations among Afro-Caribbean families: adolescent and parent perspectives. J Adolesc Res 2019; 1-31.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

24 Ganji J, Emamian MH, Maasoumi R, Keramat A, Khoei EM. Qualitative needs assessment: Iranian parents’ perspectives in sexuality education of their children. J Nurs Midwifery Sci 2018; 5(4): 140-146.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

25 Grossman JM, Richer AM, Hernandez BF, Markham CM. Moving from needs assessment to intervention: fathers’ perspectives on their needs and support for talk with teens about sex. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19(6): 3315.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

26 Guilamo-Ramos V, Bowman AS, Santa Maria D, Kabemba F, Geronimo Y. Addressing a critical gap in U.S. national teen pregnancy prevention programs: the acceptability and feasibility of father-based sexual and reproductive health interventions for latino adolescent males. J Adolesc Health 2018; 62(3s): S81-S86.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

27 Jimmyns CA, Meyer-Weitz A. “My child would never do that”: caregiver-child relationships regarding openness and communication about sexuality education in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J HIV/AIDS Soc Serv 2019; 18(4): 382-398.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

28 Kuborn S, Markham M, Astle S. “I wish they would have a class for parents about talking to their kids about sex”: college women’s parent–child sexual communication reflections and desires. Sex Res Soc Policy 2023; 20(1): 230-241.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

29 Leija SG. Sexual socialization: a qualitative exploration of immigrant latina mothers’ perception of sex-communication with their adolescent daughters. Michigan State University, Human Development and Family Studies; 2022. Available at https://books.google.ca/books?id=KElozwEACAAJ

30 Livingston JA, Allen KP, Nickerson AB, O’Hern KA. Parental perspectives on sexual abuse prevention: barriers and challenges. J Child Fam Stud 2020; 29(12): 3317-3334.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

31 Modise MA. Parent sex education beliefs in a rural South African setting. J Psychol Afr 2019; 29(1): 84-86.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

32 Othman A, Shaheen A, Otoum M, et al. Parent-child communication about sexual and reproductive health: perspectives of Jordanian and Syrian parents. Sex Reprod Health Matters 2020; 28(1): 1758444.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

33 Padilla-Walker LM. Longitudinal change in parent-adolescent communication about sexuality. J Adolesc Health 2018; 63(6): 753-758.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

34 Sandra Byers E, O’Sullivan LF, Mitra K, Sears HA. Parent-adolescent sexual communication in India: responses of middle class parents. J Fam Issues 2020; 42(4): 762-784.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

35 Scull TM, Malik CV, Keefe EM. Determining the feasibility of an online, media mediation program for parents to improve parent-child sexual health communication. J Media Lit Educ 2020; 12(1): 13-25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

36 Ustilaitė S, Petrauskienė A, Česnavičienė J. Self-assessment and expectations of mothers’ communication with adolescents on sexuality issues. Pedagogika 2023; 140(4): 116-133.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

37 Grossman JM, Lynch AD, Richer AM, DeSouza LM, Ceder I. Extended-family talk about sex and teen sexual behavior. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16(3): 480.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

38 Dagnachew Adam N, Demissie GD, Gelagay AA. Parent-adolescent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues and associated factors among preparatory and secondary school students of Dabat Town, Northwest Ethiopia. J Environ Public Health 2020; 2020: 4708091.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

39 Eleuteri S, Aminoff D, Midrio P, Leva E, Morandi A, Spinoni M, Grano C. Talking about sexuality with your own child. The perspective of the parents of children born with arm. Pediatr Surg Int 2022; 38(12): 1665-1670.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

40 Feyissa M, Nigussie T, Mamo Y, Aferu T. Adolescent girl-mother communication on sexual and reproductive health issues among students in Fiche Town, Oromia, Central Ethiopia. J Prim Care Community Health 2020; 11: 2150132720940511.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

41 Guilamo-Ramos V, Thimm-Kaiser M, Benzekri A, Rodriguez C, Fuller TR, Warner L, Koumans EHA. Father-son communication about consistent and correct condom use. Pediatrics 2019; 143(1): e20181609.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

42 Indraswari R, Shaluhiyah Z, Widjanarko B, Suryoputro A. Factors of mothers’ hesitation in discussing reproductive health. Int J Public Health Sci 2021; 10: 801-806.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

43 Katahoire AR, Banura C, Muhwezi WW, Bastien S, Wubs A, Klepp K-I, Aarø LE. Effects of a school-based intervention on frequency and quality of adolescent-parent/caregiver sexuality communication: results from a randomized-controlled trial in Uganda. AIDS Behav 2019; 23(1): 91-104.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

44 Orcasita Pineda LT, Cuenca Morales J, Montenegro Céspedes JL, Garrido Rios D, Haderlein A. Dialog and knowledge about sexuality of parents of adolescent school children. Rev Colomb Psicol 2018; 27(1): 41-53.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

45 Malango NT, Hegena TY, Assefa NA. Parent-adolescent discussion on sexual and reproductive health issues and its associated factors among parents in Sawla town, Gofa zone, Ethiopia. Reprod Health 2022; 19(1): 108.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

46 Mavhandu-Mudzusi AH, Mhlongo BG. Adolescents’ sexual education: parental involvement in a rural area in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. Afr J Nurs Midwifery 2021; 23(1): 1-15.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

47 Mihretie GN, Muche Liyeh T, Ayalew Goshu Y, Gebrehana Belay H, Abe Tasew H, Belay Ayalew A. Young-parent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues among young female night students in Amhara region, Ethiopia: community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2021; 16(6): e0253271.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

48 Nurachmah E, Afiyanti Y, Yona S, et al. Mother-daugther communication about sexual and reproductive health issues in Singkawang, West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Enferm Clin 2018; 28: 172-175.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

49 Sanghirun K, Fongkaew W, Viseskul N, Lirtmunlikaporn S. Perspectives of parents regarding sexual and reproductive health in early adolescents: a qualitative descriptive study. Pac Rim Int J Nurs Res 2021; 25(1): 60-74.

| Google Scholar |

50 Serrano J, Crouch JM, Albertson K, Ahrens KR. Stakeholder perceptions of barriers and facilitators to sexual health discussions between foster and kinship caregivers and youth in foster care: a qualitative study. Child Youth Serv Rev 2018; 88: 434-440.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

51 Simmonds JE, Parry CDH, Abdullah F, Burnhams NH, Christofides N. “Knowledge I seek because culture doesn’t work anymore … It doesn’t work, death comes”: the experiences of third-generation female caregivers (gogos) in South Africa discussing sex, sexuality and HIV and AIDS with children in their care. BMC Public Health 2021; 21(1): 470.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

52 Teppasom W, Chamroonsawasdi K, Nunthamongkolchai S, Kittipichai W, Lapvongwatana P. Challenges and obstacles of mother-daughter sexual communication among Thai rural communities: an exploratory study. J Public Hlth Dev 2021; 19(2): 28-46.

| Google Scholar |

53 Abboud S, Flores DD, Bond K, Chebli P, Brawner BM, Sommers MS. Family sex communication among Arab American young adults: a mixed-methods study. J Fam Nurs 2022; 28(2): 115-128.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

54 Agbemenu K, Hannan M, Kitutu J, Terry MA, Doswell W. “Sex will make your fingers grow thin and then you die”: the interplay of culture, myths, and taboos on African immigrant mothers’ perceptions of reproductive health education with their daughters aged 10-14 years. J Immigr Minor Health 2018; 20(3): 697-704.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

55 Depauli C, Plaute W. Parents’ and teachers’ attitudes, objections and expectations towards sexuality education in primary schools in Austria. Sex Educ 2018; 18(5): 511-526.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

56 Gabster A, Cislaghi B, Pascale JM, Francis SC, Socha E, Mayaud P. Sexual and reproductive health education and learning among Indigenous youth of the Comarca Ngäbe-Buglé, Panama. Sex Educ 2022; 22(3): 260-274.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

58 Liu T, Fuller J, Hutton A, Grant J. Congruity and divergence in perceptions of adolescent romantic experience between Chinese parents and adolescents. J Adolesc Res 2018; 35(4): 546-576.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

59 Nadeem A, Cheema MK, Zameer S. Perceptions of Muslim parents and teachers towards sex education in Pakistan. Sex Educ 2021; 21(1): 106-118.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

60 Othman A, Abuidhail J, Shaheen A, Langer A, Gausman J. Parents’ perspectives towards sexual and reproductive health and rights education among adolescents in Jordan: content, timing and preferred sources of information. Sex Educ 2022; 22(5): 628-639.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

61 Pichon M, Howard-Merrill L, Wamoyi J, Buller AM, Kyegombe N. A qualitative study exploring parent-daughter approaches for communicating about sex and transactional sex in Central Uganda: implications for comprehensive sexuality education interventions. J Adolesc 2022; 94(6): 880-891.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

62 Rahnavardi M, Bostani Khalesi Z, Rezaie-Chamani S. Parents’ and experts’ views on the sexual health education of adolescent girls: a qualitative study. Sex Relationsh Ther 2024; 39: 1145-1157.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

63 Ramchandani K, Morrison P, Gold MA, Akers AY. Messages about abstinence, delaying sexual debut and sexual decision-making in conversations between mothers and young adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2018; 31(2): 107-115.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

64 Smollin L, Valles JCG, Torres MI, Granberry PJ. Puerto Rican mothers’ conversations about sexual health with non-heterosexual youth. Cent J 2018; 30(2): 406-428.

| Google Scholar |

65 Thomas K, Patterson K, Nash R, Swabey K. What have dads got to do with it? Australian fathers’ perspectives on communicating with their young children about relationships and sexuality. Sex Educ 2022; 22(2): 169-183.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

66 Vujcich D, Lyford M, Bellottie C, Bessarab D, Thompson S. Yarning quiet ways: Aboriginal carers’ views on talking to youth about sexuality and relationships. Health Promot J Aust 2018; 29(1): 39-45.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

67 DeSouza LM, Grossman JM, Lynch AD, Richer AM. Profiles of adolescent communication with parents and extended family about sex. Fam Relat 2022; 71(3): 1286-1303.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

68 Dolev-Cohen M, Ricon T. Talking about sexting: association between parental factors and quality of communication about sexting with adolescent children in Jewish and Arab Society in Israel. J Sex Marital Ther 2022; 48(5): 429-443.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

69 Elegbe O. Sexual communication: a qualitative study of parents and adolescent girls discussion about sex. J Health Manag 2018; 20(4): 439-452.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

70 Evans R, Widman L, Kamke K, Stewart JL. Gender differences in parents’ communication with their adolescent children about sexual risk and sex-positive topics. J Sex Res 2020; 57(2): 177-188.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

71 Overbeek G, van de Bongardt D, Baams L. Buffer or brake? The role of sexuality-specific parenting in adolescents’ sexualized media consumption and sexual development. J Youth Adolesc 2018; 47(7): 1427-1439.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

72 Flores DD, Greene MZ, Taggart T. Parent-child sex communication prompts, approaches, reactions, and functions according to gay, bisexual, and queer sons. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 19(1): 74.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

73 Rubinsky V, Cooke-Jackson A. “It would be nice to know I’m allowed to exist:” designing ideal familial adolescent messages for LGBTQ women’s sexual health. Am J Sex Educ 2021; 16(2): 221-237.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

74 Isaksen KJ, Musonda P, Sandøy IF. Parent-child communication about sexual issues in Zambia: a cross sectional study of adolescent girls and their parents. BMC Public Health 2020; 20(1): 1120.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

75 Muhwezi WW, Katahoire AR, Banura C, et al. Perceptions and experiences of adolescents, parents and school administrators regarding adolescent-parent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues in urban and rural Uganda. Reprod Health 2015; 12(1): 110.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

76 Wamoyi J, Fenwick A, Urassa M, Zaba B, Stones W. Parent-child communication about sexual and reproductive health in rural Tanzania: implications for young people’s sexual health interventions. Reprod Health 2010; 7: 6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

77 Kee-Jiar Y, Shih-Hui L. A systematic review of parental attitude and preferences towards implementation of sexuality education. Int J Eval Res Educ 2020; 9(4): 971-978.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

78 Merghati-Khoei E, Abolghasemi N, Smith TG. “Children are sexually innocent”: Iranian parents’ understanding of children’s sexuality. Arch Sex Behav 2014; 43(3): 587-595.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

79 Babayanzad Ahari S, Behboodi Moghadam Z, Azin SA, et al. Concerns and educational needs of Iranian parents regarding the sexual health of their male adolescents: a qualitative study. Reprod Health 2020; 17(1): 24.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

80 Ashcraft AM, Murray PJ. Talking to parents about adolescent sexuality. Pediatr Clin North Am 2017; 64(2): 305-320.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

81 Kamaludin NN, Muhamad R, Mat Yudin Z, Zakaria R. Barriers and concerns in providing sex education among children with intellectual disabilities: experiences from Malay mothers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022; 19(3): 1070.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

82 André TG, Valdez-Montero C, Márquez-Vega MA, et al. Communication on sexuality between parents and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Sex Disabil 2020; 38(4): 217-229.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

83 Bastien S, Kajula LJ, Muhwezi WW. A review of studies of parent-child communication about sexuality and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Reprod Health 2011; 8(1): 25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

84 Fernández L, Alvarez-Cueva P, Masanet MJ.. From sexting to sexpreading: trivialization of digital violence, gender differences and collective responsibilities. Sex & Cult 2025; 29(3): 1121-1153.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

85 McKay EA, Fontenot HB. Parent-adolescent sex communication with sexual and gender minority youth: an integrated review. J Pediatr Health Care 2020; 34(6): e37-e48.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

86 UNESCO. International technical guidance on sexuality education: an evidence-informed approach; 2018. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/9789231002595