Strategies to sustain HIV prevention interventions among adolescents and young adults: analysis of data from a crowdsourcing open call in Nigeria

Ujunwa Onyeama A # * , Lauren Fidelak A # , Weiming Tang

A # * , Lauren Fidelak A # , Weiming Tang  A , Susan Nkengasong B , Titilola Gbaja-Biamila C D , Lateef Akeem C , Adesola Zaidat Musa C , Folahanmi Tomiwa Akinsolu C E , Tomilola Musari-Martins

A , Susan Nkengasong B , Titilola Gbaja-Biamila C D , Lateef Akeem C , Adesola Zaidat Musa C , Folahanmi Tomiwa Akinsolu C E , Tomilola Musari-Martins  C , Jane Okwuzu C , Aishat Adedoyin Koledowo D , Suzanne Day F , Temitope Ojo F , Olufunto A. Olusanya F , Kadija M. Tahlil G , Donaldson F. Conserve H , Oluwaseun Adebayo Bamodu H , Nora E. Rosenberg I , Ucheoma Nwaozuru J , Chisom Obiezu-Umeh K , Collins Airhihenbuwa L , Oliver Ezechi C D , Juliet Iwelunmor F and Joseph D. Tucker

C , Jane Okwuzu C , Aishat Adedoyin Koledowo D , Suzanne Day F , Temitope Ojo F , Olufunto A. Olusanya F , Kadija M. Tahlil G , Donaldson F. Conserve H , Oluwaseun Adebayo Bamodu H , Nora E. Rosenberg I , Ucheoma Nwaozuru J , Chisom Obiezu-Umeh K , Collins Airhihenbuwa L , Oliver Ezechi C D , Juliet Iwelunmor F and Joseph D. Tucker  A B *

A B *

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

# These authors contributed equally to this paper

Handling Editor: Megan Lim

Abstract

Crowdsourcing is a process whereby a large group, including experts and non-experts, collaborate to solve a problem and then share the solution with the public. Crowdsourcing can be used to identify strategies to sustain HIV services in low-and-middle-income countries. This study aims to identify innovative adolescent and young adult (AYA) solutions through a crowdsourcing open call to sustain HIV services.

Building on HIV prevention services developed by AYA from an initial open call, we organized a crowdsourcing open call to identify innovative, AYA-led strategies to sustain these services through partnerships with the community. The open call question was, ‘How might we sustain the 4 Youth by Youth HIV prevention services while nurturing our existing relationships, practices, procedures and services that will last in our communities?’. All submissions were assessed based on prespecified judging criteria. Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic analysis and categorized into strategies for sustaining AYA-friendly HIV prevention services in Nigeria.

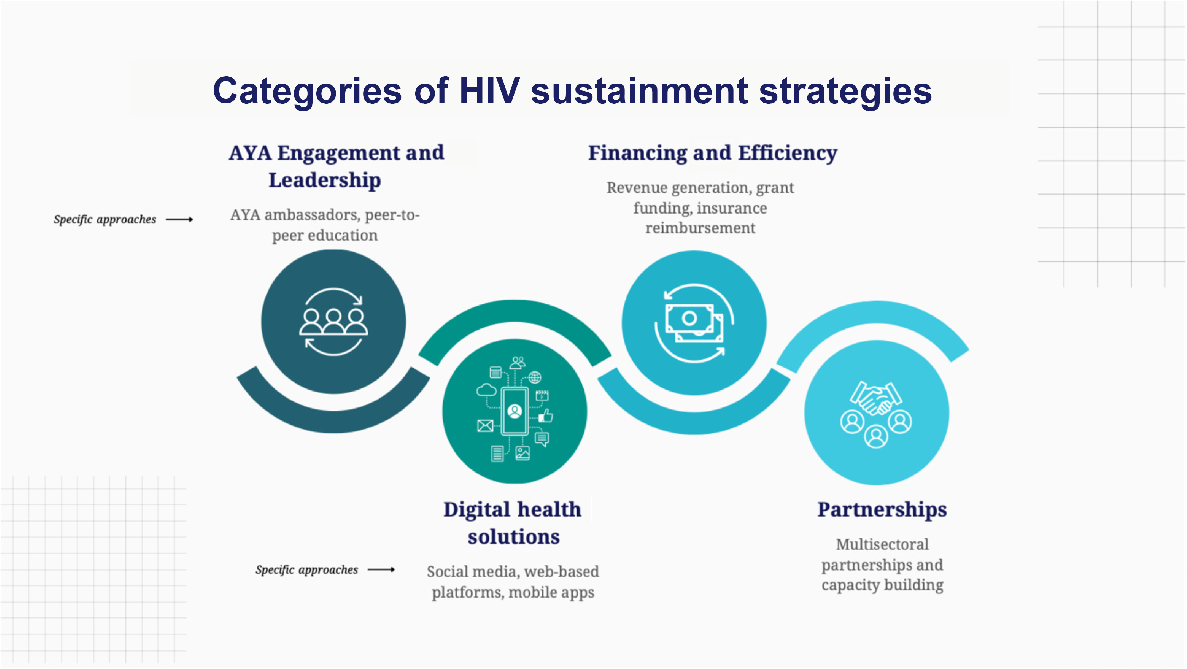

We received 102 eligible submissions from AYA. Twenty-three submissions met the mean score threshold and were qualitatively analyzed. Through this analysis, we identified four strategies for sustaining AYA-friendly HIV prevention services in Nigeria: AYA engagement and leadership in research, digital health solutions, financing and efficiency, and partnerships.

This open call highlights how strategies developed by AYA may sustain AYA-friendly HIV prevention services. Our findings offer key insights for maintaining HIV prevention services in Nigeria and other similar settings.

Keywords: 4YBY, adolescents, AYA, AYA-friendly strategies, crowdsourcing, HIV prevention, open call, sustainability, young adults.

Background

Adolescents and young adults (AYA; aged 14–24 years) in Africa bear a disproportionate burden of HIV infection, accounting for almost one-third of all new HIV infections.1 When seeking sexual and reproductive health services, AYA often face age-related stigma. This interferes with HIV prevention and treatment,2,3 highlighting the importance of developing AYA-friendly HIV services. AYA-friendly HIV services refer to those that provide a comfortable and safe setting for AYA to meet their service needs, and ensure uptake and retention.4 To fit within the WHO quality of care framework, these services must be accessible, acceptable, equitable, appropriate and effective.5 Although many evidence-based HIV strategies6,7 for developing AYA-friendly services exist, few studies have focused on evaluating the sustainability of these strategies.8 The sustainability of AYA HIV strategies is crucial to achieving public health impact by ensuring that programs or interventions continue delivering benefits over time, retain participants, strengthen local capacity and potentially integrate into existing health systems.9–12 All of these can lead to long-term improvements in health outcomes.

AYA engagement is important in identifying mechanisms to sustain HIV services.13 This engagement, defined as ‘the active, informed, and voluntary involvement of AYA in decision-making related to the health and life of their communities,’ is key to ensuring HIV policies and programs address their needs.13 Additionally, substantial AYA engagement in the design and delivery of HIV interventions has been shown to enhance the reach and acceptability of interventions,9 and increase the likelihood of local ownership and sustainability.14,15 Much of the existing literature focuses on immediate implementation outcomes, neglecting long-term sustainability.8 This suggests the need for more comprehensive approaches that prioritize AYA’s unique needs and preferences.16 A Nigerian Institute of Medical Research consensus statement highlighted the importance of sustaining AYA HIV interventions.17 The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS has similarly called for greater attention to sustainability.18 The 2019 Nigerian HIV/AIDS Sustainability Index and Dashboard revealed limited sustainability, underscoring the need to strengthen efforts to enhance the sustainability and effectiveness of programs and services.19 Furthermore, the National Agency for the Control of AIDS recommended that planning for sustainability should be integral to all aspects of programming.20

To address the lack of sustainment strategies while ensuring the meaningful engagement of AYA, our team launched a national crowdsourcing open call to identify strategies to enhance the sustainability of HIV prevention interventions in Nigeria. Crowdsourcing is a process whereby a large group, including experts and non-experts, collaborate to solve a problem and then share the solution with the public.21,22 Crowdsourcing has many people contribute ideas, and implements the top ideas based on the mean score from independent judge assessments.21 Crowdsourcing has been used among African AYA to develop HIV testing strategies17,21,23,24 and inform sexual health policies.25 This suggests that crowdsourcing could be an effective, youth-led approach to identifying sustainability strategies for AYA-friendly HIV prevention interventions in Nigeria.

This manuscript summarizes the open call findings, and highlights AYA-generated strategies for sustaining HIV prevention in Nigeria.

Methods

Crowdsourcing open call

Our research team, in collaboration with 4 Youth By Youth (4YBY) – a program aimed at engaging Nigerian AYA in innovative HIV prevention efforts22 – organized a crowdsourcing open call. The crowdsourcing open call aimed to identify innovative, AYA-led strategies to sustain 4YBY HIV preventive services through partnerships in the community. AYA aged between 14 years and 24 years living in Nigeria were eligible to submit ideas. AYA could submit as individuals or as part of a team. Demographic and other data were collected from only one designated member for team submissions.

The Nigerian Institute for Medical Research organized the open call in partnership with St. Louis University, Washington University in St. Louis and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The project was guided by a youth advisory board, including AYA, who had been identified through crowdsourcing activities or worked as part of the research team. Each youth advisory board member had experience working in HIV prevention and youth engagement. They provided feedback on study design and strategies to ensure the project remained AYA centered. The open call was promoted on the 4YBY website, Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp and partner organizations (Fig. 1).

Submissions were accepted between 25 October and 25 November 2022. Participants were asked to respond to the prompt, ‘How might we sustain the 4 Youth by Youth HIV prevention services while nurturing our existing relationships, practices, procedures and services that will last in our communities?’ Sustainability was described to participants as programs or services that continue to be delivered effectively or as intended while allowing for adaptation and evolution over time.26 The focus on 4YBY provided participants with a specific set of elements from its protocol22 – HIV self-testing (HIVST), a participatory learning community, peer support, and on-site supervision – to develop their strategies around, anchoring their attempts to think through new possibilities for sustaining AYA-friendly services.

Two research team members screened all submissions to assess eligibility (i.e. whether the submission contains an idea in response to the open call prompt). A judging team then evaluated all eligible submissions. The judging team consisted of a panel of six people, including public health professionals, researchers working with youth and youth advisory board members. Including AYA as part of the judging team ensured that AYA perspectives were directly considered in determining the desirability level. Judges were asked to assign a score to each submission based on a scale of 1–10 (one being lowest quality, 10 being highest quality) using five judging criteria: clear description of the proposed solution; desirability of the proposed solution to AYA; innovation; feasibility of the services among AYA; and potential for the solution to have a positive impact on the sustainability of 4YBY HIV prevention services in Nigeria. Desirability was specifically assessed based on whether the idea was appealing (interesting to youth) and met the needs (low-cost, accessible, confidential) of AYA. Feasibility was the degree to which the idea could be implemented, widely acceptable and realistic to put into place. The impact was the potential for sustaining 4YBY among AYA in Nigeria. The six judges evaluated each submission, and a final mean score was calculated for each. Submissions with a mean score of ≥6.0 were selected for thematic analysis; among these, submissions scoring ≥7.0 advanced to the semifinals and were invited to pitch their submissions during a World AIDS Day Event on 1 December 2022. An independent judging panel reviewed oral presentations from semifinalists. The three highest-scoring teams were awarded prize money, approximately US$563 (250,000 Naira), US$337 (150,000 Naira) and US$112 (50,000 Naira) for the respective first, second and third-place finalists.

Data collection

Promotional materials were shared via email and WhatsApp, and other social media platforms. Submissions in response to the open call prompt could be made in the form of text (500 words maximum), image (5 MB maximum) or video (3 min maximum). These were submitted through a Google Form on the 4YBY website, and participants submitting digital entries (image or video) were instructed to send their files via email. Submissions were accepted in English, as specified in the open call guidelines. Demographic data, including age, sex, highest education level and employment status, were collected for only the team members who submitted to the open call.

Data management and analysis

A single dataset was created from all submissions and merged with the scoring dataset using the submission numbers created during the initial application process. All submissions with a final mean score of ≥6.0/10 were selected for descriptive analysis (distinct from the higher threshold used for semifinal selection). Submissions with a mean score of <6.0 were excluded because they were: (1) less clearly articulated, (2) lacked sufficient quality, or (3) did not address the open call topic. An additional dataset was created with the submission content for those that scored >6.0, and the dataset was cleaned to remove redundant submissions. We conducted a descriptive analysis of open call data from this dataset.

Qualitative analysis

Submissions were analyzed qualitatively using thematic analysis, applying open coding to identify emergent themes.27 We developed a codebook through an inductive process.28 The inductive process began with developing a submission codebook containing main codes, sub-codes, decisional rules and examples guiding the application. The qualitative analysis involved two rounds of coding conducted by two coders – LF and CO. The coders were research team members who had experience conducting qualitative data analysis. To ensure consistency in coding, they double coded a subset of the data. Consensus meetings were held with a third person, JT, resolving any discrepancies. Although the coding process was inductive, the Dynamic Sustainability Framework29 was later applied (more details in the ‘Theoretical Framework’ below) deductively to organize the emerging themes into core elements.

Demographic data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. For categorical variables, numbers and percentages were presented. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the 102 eligible participants who submitted ideas to the open call. Data were stored and protected on the Saint Louis University Oracle Relational Database Management System. The dataset was maintained in Excel and used for the descriptive analysis, including calculating frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. The codebook was developed collaboratively using Google Docs.

| Number (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||

| 14–17 | 30 (29.4) | |

| 18–21 | 31 (30.4) | |

| 22–24 | 41 (40.2) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 53 (52.0) | |

| Female | 49 (48.0) | |

| Highest education level completed | ||

| Primary | 1 (1.0) | |

| Secondary (senior and junior) | 64 (62.7) | |

| Tertiary education A | 37 (36.3) | |

| Employment status | ||

| Student | 87 (85.3) | |

| Employed | 3 (3.0) | |

| Serving corp member | 3 (3.0) | |

| Volunteer | 2 (2.0) | |

| Unemployed | 6 (5.9) | |

| Other | 1 (1.0) | |

We adapted the Dynamic Sustainability Framework.29 This framework has three core elements – the intervention, the context in which the intervention is delivered and the broader ecological system. Additionally, the Dynamic Sustainability Framework distinctly considers the evolution of these elements over time, recognizing that sustainability is not static, but shaped by adaptation. These contextual factors and the broader ecological system directly impact the ability of an intervention to reach the intended population and provide sustainable benefits. The Dynamic Sustainability Framework was appropriate for this study, because it focuses on sustainment strategies and acknowledges the dynamic nature of HIV services. Textual themes were examined using the three elements of the Dynamic Sustainability Framework. By using this framework, we could map the diverse strategies submitted into these elements, ensuring alignment with a sustainability-focused perspective. Given the focus of the data, we adapted the framework, and mapped themes to intervention and context. The adaptation of the Dynamic Sustainability Framework used in this work is shown in Table 2.

| Sustainability element | Categories | Specific approaches | Anticipated outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | AYA leadership and engagement | AYA ambassadors Peer-to-peer education School-based training programs | Increased AYA engagement Increased awareness of 4YBY programs and services Increased uptake of PrEP, HIVST and other HIV testing services | |

| Digital health solutions | Social media campaigns Online/web-based educational platforms Gamification Web-based applications and platforms | Increased awareness of 4YBY programs and services Increased access to HIVST and increased HIV testing Reduced stigma and misconceptions Increased self-efficacy Linkage to AYA-friendly care | ||

| Financing and efficiency | Revenue generation through mobile and web-based applications Grant funding Reimbursement from insurance providers Subsidized costs for HIVST kits | Sustainable funding for programs Increased access to HIVST Increased HIV testing | ||

| Context | Multisectoral partnerships | Collaborations with non-governmental organizations, community-based organizations, health tech startups, and/or private enterprises, universities, and health departments Government partnerships Capacity building | Meaningful community engagement Establishing a presence in different regions of Nigeria Enhanced local service delivery networks and channels Improved linkage to care Enhanced AYA training and mentorship opportunities |

Ethical approval

Regulatory approval to conduct the research was received from the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research Institutional Review Board (IRB number IRB/18/028) and the Saint Louis University Institutional Review Board (IRB number 29425). Anonymized data with participant sociodemographic information were collected.

Results

Open call participants

A total of 106 submissions to the open call were received. Of those, 102 were deemed eligible. Among those eligible for the contest, 53 (52%) were men. Submissions were distributed across age groups, with an age range of 14–24 years and a median age of 21 years. Of the 102 eligible entries, 21 were group submissions, with group sizes ranging from two to four participants, including 18 groups of two participants, two groups of four participants and one group of three participants. Most of the entries were text-based, with some participants submitting digital entries in addition to their text. The review process evaluated every element of each entry. Following evaluation based on predefined judging criteria, 23 submissions met the final mean score threshold of ≥6.0 and were included in the thematic analysis. Among these, three were digital entries.

Semifinalists

Of the 23 submissions included in the thematic analysis, the top 13 submissions (those that scored ≥7.0) advanced to the semifinals. These semifinalists presented at the annual World AIDS Day event. Each individual/group presentation was assessed by four independent judges, including members of the youth advisory board and steering committee. The top three participants were selected based on mean scores from the judges.

Descriptive analysis

Twenty-three entries had a mean score of >6.0. Of them, 43.4% (10/23) of submissions specifically mentioned the sustainability of existing 4YBY programs, whereas the others proposed new programs, interventions or strategies. Table S1 shows the themes from the top five ideas in the open call.

Four common categories (Fig. 2) emerged from the analysis of sustainment strategies for AYA HIV programs: AYA engagement and leadership in research (17 submissions), digital health solutions (16 submissions), financing and efficiency (eight submissions), and partnerships (13 submissions) (Table 3). Additionally, each strategy had descriptive sub-categories. Although some submissions covered only one strategy, many entries included two or more strategies and sub-strategies (Table 4).

| Theme | Example quote from the submissions | |

|---|---|---|

| AYA engagement and leadership in research | ‘The fellows serve as ambassadors of 4YBY in their regions, promote organization goals and preventive services, and aid crowdsourcing for people/ideas for 4YBY events and services.’ #1, Male, 23 years old. | |

| Digital health solutions | ‘To begin with, social media has become one of the biggest mediums of communication among youths, Nigeria is no exception in this. By ensuring appropriate curated communities on social media, information can be easily disseminated and increases social engagement to a wider reach of people.’ #64, Male, 19 years old. | |

| Financing and efficiency | ‘The revenue generated from product sales and user fees can be used to meet its financial obligations.’ #12, Male, 23 years old. | |

| Partnerships | ‘…Partnering with pharmacy shops to sell this 4YBY self-test kit to their customers as these pharmacies, or ‘chemists’, are the first contact line of most Nigerian youth regarding their health.’ #71, Male, 22 years old. |

Table 3 provides selected illustrative quotes representing key sustainment strategies. Additional quotes can be found in Supplementary material Table S2.

| Strategy | No. of submissions (%) A | Sub-strategies (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AYA capacity building and leadership in research | 17 (74.0) |

| |

| Digital health solutions | 16 (69.6) |

| |

| Financing and efficiency | 8 (34.8) |

| |

| Partnerships | 13 (56.5) |

|

A total of 17 submissions described how AYA capacity building and leadership could increase sustainability. We define capacity building as programs that educate and/or train AYA to become advocates or to lead their interventions. Submissions in this category suggested training AYA through peer-to-peer (Supplement 2, #61), school-based (Supplement 2, #12) and fellowships (Supplement 2, #74). Training and education among submissions in this category extended past HIV prevention education, also focusing on leadership development, ownership of research (Supplement 2, #61) and ambassador programs (Supplement #2, #1) in which AYA would serve as advocates and implement 4YBY programs in their community, thereby creating self-sustaining, AYA-led programs.

Strategies incorporating social media and technology aimed to increase the reach and integration of 4YBY programs. A total of 16 submissions mentioned social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram) and/or technology (app- or web-based tools) to sustain 4YBY services. Mobile applications provided a centralized location for education and training (Supplement 2, #30) and revenue generation through web-based platforms (Supplement 2, #80). Online marketplaces were also proposed through unstructured supplemental service data (Supplement 2, #1) and other online locations (Supplement 2, #80) to generate revenue for 4YBY and its community partners. Furthermore, social media campaigns can serve educational (Supplement 2, #64) and marketing purposes (Supplement 2, #64), increasing awareness of 4YBY, and driving continued engagement with 4YBY and community partner services.

Eight submissions referenced financing and efficiency as a sustainability strategy. Financing and efficiency allow 4YBY to sustain programs at the end of current grant funding. Revenue generation was primarily suggested by selling HIVST kits through online, secure marketplaces (Supplement 2, #12). Insurance reimbursement (Supplement 2, #72) for services provided by 4YBY may also generate revenue to sustain programs. Public and private grant funding (Supplement 2, #47) allows for the temporary continuation of programs and the initiation of new AYA-led interventions. Additionally, training AYA to write and apply for their grant funding (Supplement 2, #47) could extend some 4YBY components. Partnerships to subsidize HIVST kits (Supplement 2, #76) promote efficient and affordable purchasing options for AYA.

A total of 13 submissions mentioned partnerships to ensure 4YBY sustainability. Multisectoral partnerships embed 4YBY services and programs into community, government, and health frameworks. Partnerships, particularly those that span several sectors (Supplement 2, #71), embed 4YBY services and programs into the local, state, federal, and health infrastructures. School- and university-based partnerships (Supplement 2, #42) allowed for long-lasting, self-sustaining partnerships through which student trainees may educate their peers and train the next generation of 4YBY educators. Community-based partnerships (Supplement 2, #72) integrate 4YBY services into pre-existing community programs, ensuring trust and programmatic reach. Overall, partnerships may institutionalize AYA-friendly services into local and national infrastructures, leading to continued support and sustainability of programs (Supplement 2, #12).

Table 2 summarizes the findings of our analysis, mapping the submissions onto the elements of the Dynamic Sustainability Framework.

Discussion

We organized a crowdsourcing open call to collect strategies to sustain AYA-friendly HIV prevention programs for AYA in Nigeria. Our crowdsourcing approach may have helped us identify more ideas regarding sustainment strategies from AYA in Nigeria compared with a conventional scoping or systematic literature review. By directly engaging AYA in Nigeria, this approach ensured that lived experiences informed the proposed strategies.30 Previous research has shown that crowdsourcing open calls can provide locally relevant innovative solutions that may be overlooked in top-down, expert-driven processes.31 The analysis of sustainment strategies for AYA-friendly HIV preventive service programs identified four categories – AYA leadership and engagement, digital health solutions, financing and efficiency, and partnerships. This manuscript expands the literature by focusing on sustainability, including a participatory process to solicit AYA ideas and centering perspectives from an LMIC setting.

The most common interventions identified centered around AYA leadership and engagement, digital health solutions, and financing. These appeared to primarily focus on education, AYA engagement, social media and innovative revenue generation to increase awareness of HIV prevention efforts. Sustaining AYA-friendly HIV prevention requires strong youth leadership and engagement.6 Several submissions align with this, highlighting the need for continued AYA and community engagement. These submissions describe specific methods for developing AYA capacity and ensuring AYA engagement, from identifying and training AYA ambassadors to serve as peer educators and champions to utilizing the reach and power of social media to drive engagement within this group. Previous research has emphasized AYA-centred approaches and are consistent with our findings.6,32 For example, a crowdsourcing study across 15 African countries found that AYA not only benefit from, but also actively contribute to, research and community-level capacity-building.6 Similarly, a Zambian study found that AYA was uniquely positioned to connect with and support AYA living with HIV, reinforcing the importance of youth leadership in sustaining HIV prevention efforts.32 Beyond playing a critical role in HIV prevention efforts, AYA engagement also ensures these strategies fit the context in which they are implemented.33 This is relevant, because expert-driven processes that lack AYA input tend to promulgate programs/services that do not address the needs, priorities and unique experiences of AYAs.34 This lack of appropriate AYA engagement represents missed opportunities to build a more inclusive and sustainable HIV response.13

Our data also suggest innovative financing strategies may be important for sustaining AYA HIV services in Nigeria. This is consistent with other literature on how best to finance HIV services in LMICs.35–38 Potential financial strategies included the online sale of HIVST kits to generate revenue, integrating the 4YBY intervention into the National Health Insurance Scheme, and using mobile/web-based platforms to generate revenue and grant funding opportunities. Notably, integrating HIV services into the national insurance scheme is consistent with ongoing national efforts.39 Additionally, submissions emphasize the crucial role of technology in sustaining AYA-friendly HIV prevention. Digital health solutions, by way of social media, mobile apps and web-based platforms were suggested as effective ways to reach, educate and engage AYA, to improve awareness and sustainability. This is also consistent with other research on the pivotal role of digital engagement.6

Several submissions recognize that an intervention must fit within the setting and context to be effective and sustained. Across the submissions, building robust partnerships with NGOs, educational institutions and government entities emerged as key strategies. These multisectoral partnerships – collaborative partnerships between 4YBY and several organizations in diverse fields, from NGOs to educational institutions and government agencies – were described as important in ensuring sustainability of HIV prevention efforts. This aligns with global recommendations. For instance, the WHO has recommended appropriately integrating AYA-friendly health services within HIV programs, because adaptation to the local context is crucial in ensuring the services are relevant and effective.40 These submissions emphasize that the multisectoral partnerships are essential for integrating services into primary health systems and community-based organizations, and more to improve linkage to care, enhance local service delivery networks, promote mentorship, and ultimately create structural support and sustain impact. Additionally, training and supervision efforts to build capacity among AYA were noted as essential for driving sustainment. Together, these multisectoral partnerships could bridge resource gaps and embed services within existing infrastructure for longevity,41,42 and strengthen the overall capacity of various sectors to improve AYA’s health outcome.13

Our study has some limitations. First, the open call question asked participants to propose strategies to sustain 4YBY programs, and our findings may not be generalizable in sustaining other HIV programs. However, focusing responses on 4YBY provided participants with concrete examples of HIV prevention programs to help make participation in generating ideas more accessible to AYA with limited knowledge of existing HIV services. Second, the open call required people to have internet access to submit their strategies. This likely encouraged higher-income participants. Third, excluding submissions <6.0 may have introduced some selection bias. Fourth, the judging criteria may have been interpreted differently by different judges. However, all judging was independent; each judge had a rubric, and we followed WHO/Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases best practices for crowdsourcing open calls.21 Fifth, demographic data were only collected for one member of each team.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that AYA can serve a critical role in developing strategies to sustain HIV prevention interventions. In the face of implementation and sustainability barriers, the expertise of AYA may be integrated into interventions via participatory methods, such as crowdsourcing, to promote innovation and AYA-driven solutions to public health problems in their communities. Furthermore, the development of four strategic sustainability domains consistent with previous frameworks suggests that this process is effective in generating comprehensive, evidence-informed sustainability plans for AYA-friendly HIV prevention services in Nigeria. This process may be used in other LMICs to develop AYA-led, tailored responses to sustainability barriers in their HIV prevention programs.

Future directions

Although several strategies proposed have been utilized in other settings,14 their applicability to sustaining HIV prevention services in Nigeria remains to be tested. Further research is needed to assess how these strategies can fit the local context.

Conflicts of interest

Joseph Tucker is co-Editor in Chief for Sexual Health, and Weiming Tang and Ucheoma Nwaozuru are Associate Editors for Sexual Health, but were not involved in the peer review or decision-making process for this paper. The authors declare that they have no other potential conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank 4 Youth by Youth (4YBY), the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research, youth advisory board members, and organizing and steering committees for supporting this crowdsourcing open call.

References

1 Wong VJ, Murray KR, Phelps BR, Vermund SH, McCarraher DR. Adolescents, young people, and the 90–90–90 goals a call to improve HIV testing and linkage to treatment. AIDS 2017; 31: S191-S194.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

2 Winskell K, Singleton R, Sabben G, et al. Social representations of the prevention of heterosexual transmission of HIV among young Africans from five countries, 1997–2014. PLoS ONE 2020; 15(3): e0227878.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 Nyblade L, Mingkwan P, Stockton MA. Stigma reduction: an essential ingredient to ending AIDS by 2030. Lancet HIV 2021; 8(2): e106-e113.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

4 Gausman J, Othman A, Al-Qotob R, et al. Measuring health service providers’ attitudes towards the provision of youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services: a psychometric study to develop and validate a scale in Jordan. BMJ Open 2022; 12(2): e052118.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

5 World Health Organization. Making health services adolescent friendly: developing national quality standards for adolescent friendly health services. World Health Organization; 2012. Available at https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/75217 [accessed 11 February 2025]

6 Tahlil KM, Rachal L, Gbajabiamila T, et al. Assessing engagement of adolescents and young adults (AYA) in HIV research: a multi-method analysis of a crowdsourcing open call and typology of aya engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Behav 2023; 27(S1): 116-127.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

7 Dunn Navarra A-M, Gormley M, Liang E, et al. Developing and testing a web-based platform for antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence support among adolescents and young adults (AYA) living with HIV. PEC Innov 2024; 4: 100263.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

8 Vorkoper S, Tahlil KM, Sam-Agudu NA, et al. Implementation science for the prevention and treatment of HIV among adolescents and young adults in Sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. AIDS Behav 2023; 27(S1): 7-23.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

9 Iwelunmor J, Blackstone S, Veira D, et al. Toward the sustainability of health interventions implemented in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and conceptual framework. Implement Sci 2016; 11(1): 43.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

10 Moore JE, Mascarenhas A, Bain J, Straus SE. Developing a comprehensive definition of sustainability. Implement Sci 2017; 12(1): 110.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

11 Hall A, Shoesmith A, Doherty E, et al. Evaluation of measures of sustainability and sustainability determinants for use in community, public health, and clinical settings: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2022; 17(1): 81.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

12 Shelton RC, Cooper BR, Stirman SW. The sustainability of evidence-based interventions and practices in public health and health care. Annu Rev Public Health 2018; 39(1): 55-76.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

13 UNAIDS. Ending the AIDS epidemic for adolescents, with adolescents. 2016. Available at https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2016/ending-AIDS-epidemic-adolescents

14 Herlitz L, MacIntyre H, Osborn T, Bonell C. The sustainability of public health interventions in schools: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2020; 15(1): 4.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

15 Schell SF, Luke DA, Schooley MW, et al. Public health program capacity for sustainability: a new framework. Implement Sci 2013; 8(1): 15.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

16 Pettifor A, Bekker L-G, Hosek S, et al. Preventing HIV among young people: research priorities for the future. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013; 63(Supplement 2): S155-S160.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

17 Day S, Tahlil KM, Shah SJ, et al. The HIV open call on informed consent and ethics in research (VOICE) for adolescents and young adults: a digital crowdsourcing open call in low- and middle-income countries. Sex Transm Dis 2024; 51(5): 359-366.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

18 Jointed United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). HIV response sustainability primer. UNAIDS; 2024. Available at https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2024/20240117_HIV_response_sustainability

19 U.S. Department of State. 2019 Sustainability index and dashboard summary: Nigeria. 2019. Available at https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Nigeria-SID-2019.pdf

20 National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA). National HIV strategy for adolescents and young people 2016–2020. National Agency for the Control of AIDS, NACA; 2016. Available at https://naca.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/National-HIV-Strategy-For-Adolescents-and-Young-People.pdf

21 Han L, Chen A, Wei S, Ong JJ, Iwelunmor J, Tucker JD. Crowdsourcing in health and health research: a practical guide. World Health Organization (WHO); 2018. Available at https://apo.who.int/publications/i/item/2018-07-11-crowdsourcing-in-health-and-health-research-a-practical-guide [accessed 17 July 2024]

22 Iwelunmor J, Tucker JD, Obiezu-Umeh C, et al. The 4 Youth by Youth (4YBY) pragmatic trial to enhance HIV self-testing uptake and sustainability: study protocol in Nigeria. Contemp Clin Trials 2022; 114: 106628.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

23 Iwelunmor J, Ezechi O, Obiezu-Umeh C, et al. Enhancing HIV self-testing among Nigerian youth: feasibility and preliminary efficacy of the 4 Youth by Youth Study using crowdsourced youth-led strategies. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2022; 36(2): 64-72.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

24 Rosenberg NE, Obiezu-Umeh C, Gbaja-Biamila T, et al. Strategies for enhancing uptake of HIV self-testing among Nigerian youths: a descriptive analysis of the 4YouthByYouth crowdsourcing contest. BMJ Innov 2021; 7(3): 590-596.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

25 Hildebrand M, Ahumada C, Watson S. CrowdOutAIDS: crowdsourcing youth perspectives for action. Reprod Health Matters 2013; 21(41): 57-68.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

26 Scheirer MA, Dearing JW. An agenda for research on the sustainability of public health programs. Am J Public Health 2011; 101(11): 2059-2067.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

27 Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research (3rd Ed.): techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2008. 10.4135/9781452230153

28 Naeem M, Ozuem W, Howell K, Ranfagni S. A step-by-step process of thematic analysis to develop a conceptual model in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods 2023; 22: 16094069231205789.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

29 Chambers DA, Glasgow RE, Stange KC. The dynamic sustainability framework: addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement Sci 2013; 8(1): 117.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

30 Iwelunmor J, Ezechi O, Obiezu-Umeh C, et al. The 4 youth by youth HIV self-testing crowdsourcing contest: a qualitative evaluation. PLoS ONE 2020; 15(5): e0233698.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

31 Tang W, Han L, Best J, et al. Crowdsourcing HIV test promotion videos: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial in China. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62(11): 1436-1442.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

32 Abrams EA, Burke VM, Merrill KG, et al. “Adolescents do not only require ARVs and adherence counseling”: a qualitative investigation of health care provider experiences with an HIV youth peer mentoring program in Ndola, Zambia. PLoS ONE 2021; 16(6): e0252349.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

33 Iwelunmor J, Ezechi O, Obiezu-Umeh C, et al. Tracking adaptation strategies of an HIV prevention intervention among youth in Nigeria: a theoretically informed case study analysis of the 4 Youth by Youth Project. Implement Sci Commun 2023; 4(1): 44.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

34 Reed SJ, Miller RL, The Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. The benefits of youth engagement in HIV-preventive structural change interventions. Youth Soc 2014; 46(4): 529-547.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

35 Zakumumpa H, Bennett S, Ssengooba F. Leveraging the lessons learned from financing HIV programs to advance the universal health coverage (UHC) agenda in the East African Community. Glob Health Res Policy 2019; 4(1): 27.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

36 Itiola AJ, Agu KA. Country ownership and sustainability of Nigeria’s HIV/AIDS supply chain system: qualitative perceptions of progress, challenges and prospects. J Pharm Policy Pract 2018; 11(1): 21.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

37 Ogbuabor D, Olwande C, Semini I, Onwujekwe O, Olaifa Y, Ukanwa C. Stakeholders’ perspectives on the financial sustainability of the HIV response in Nigeria: a qualitative study. Glob Health Sci Pract 2023; 11(2): e2200430.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

38 Remme M, Siapka M, Sterck O, Ncube M, Watts C, Vassall A. Financing the HIV response in sub-Saharan Africa from domestic sources: Moving beyond a normative approach. Soc Sci Med 2016; 169: 66-76.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

39 Nwizu J, Ihekanandu U, Ilika F. Increasing domestic financing for the HIV/AIDS response in Nigeria: a catalyst to self-reliance. Lancet Glob Health 2022; 10: S25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

40 World Health Organization (WHO). Adolescent-friendly health services for adolescents living with HIV: from theory to practice. World Health Organization (WHO); 2019. Available at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/adolescent-friendly-health-services-for-adolescents-living-with-hiv

41 Musuka G, Moyo E, Cuadros D, Herrera H, Dzinamarira T. Redefining HIV care: a path toward sustainability post-UNAIDS 95-95-95 targets. Front Public Health 2023; 11: 1273720.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

42 Bulstra CA, Hontelez JAC, Otto M, et al. Integrating HIV services and other health services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2021; 18(11): e1003836.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |