Population structure, growth and reproduction in two species of Tympanocryptis (Agamidae)

Lyn Nelson A and Paul D. Cooper A *

A *

A

Abstract

Two threatened species of Tympanocryptis (T. lineata and T. osbornei) (the grassland earless dragon clade) are compared for population structure, growth and reproduction from sites around the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and near Cooma in New South Wales (NSW). Both species showed similar proportions of adults, intermediates and juveniles, as well as similar proportions of adult males and females. Growth patterns had a rapid increase in snout–vent length (SVL) in juveniles. Predicted adult SVL was the same in both species, and females in both species had greater SVL than males. In one year, the appearance of juveniles in the populations was later in T. osbornei than in T. lineata, but that may have been a result of cooler temperatures in the austral summer. Body condition was slightly better in adults of T. osbornei than T. lineata as the former were heavier and shorter. Longevity in the field was similar for both species, being slightly greater than two years, but reproduction may have occurred only once during their lifetime. Colouration associated with reproduction appeared to be the same for both species. Future work can use this information to determine how populations of Tympanocryptis sp. vary in response to environmental changes.

Keywords: conservation ecology, earless dragons, endangered species, grassland habitats, herpetology, life history, lizard biology, population biology.

Introduction

Lizard life histories often show phenotypic plasticity by varying in response to temperature, food availability and other environmental factors (Adolph and Porter 1993, 1996). Populations of lizards in the Tympanocryptis lineata clade (grassland earless dragons) were known to be present in grasslands from north of Melbourne, Victoria, through to the Monaro Plains of New South Wales (NSW) and continuing north to Bathurst, NSW, and potentially to the Darling Downs region of Queensland (Smith et al. 1999). This distribution encompasses a wide variety of environmental factors associated with changes in both latitude and altitude. Recently, rather than being two grassland species as thought (Smith et al. 1999; Scott and Keogh 2000; Melville et al. 2007), the taxonomy has indicated that several grassland earless dragon species are present (Melville et al. 2019). Unfortunately, the only extant populations are from around the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) (T. lineata), Cooma (NSW) (T. osbornei) and possibly Bathurst (NSW) (T. mccartneyi) (Melville et al. 2019), and a recently rediscovered species in Victoria (T. pinguicolla) (Anonymous 2023). Three of the four species (T. lineata, T. mccartneyi and T. pinguicolla) are listed as Critically Endangered, whereas T. osbornei is listed as Endangered under Australia’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

Since the splitting of the T. lineata clade into four species, an understanding of the potential differences in biology have become more important (Anonymous 2023). Although the length of life and the reproductive periods have been suggested previously (Anonymous 2023), the number of animals used for these estimations has been marginal for statistical purposes. Part of the problem has been that the animals are limited when capturing even under the best of conditions, and detectability challenges may play a role in their status (Anonymous 2023). Although the genetics have been used to separate the species, the actual biological information that may support that is largely unknown. This is especially true for T. mccartneyi from around Bathurst and the newly rediscovered T. pinguicolla from Victoria (Anonymous 2023).

Most extant populations of these small, cryptic, oviparous lizard species are assumed to have similar diets and activity patterns in the field (Anonymous 2023), but only the life history characteristics of the most studied populations of T. lineata in the ACT region have been described (Smith 1994; Langston 1996; Nelson 2004; Stevens et al. 2010; Nelson and Cooper 2017). Because of the distance and altitude differences between T. lineata in the ACT and T. osbornei from around Cooma, NSW, we have compared the growth and other life history patterns that exist between these species over three years when lizards were more numerous at the beginning of the millennium drought that affected most of southern Australia (Bureau of Meteorology 1996–2003). We focussed especially on population structure, recruitment, growth rates, adult male and female body size, longevity, and condition of juveniles, intermediates and adults over at least two years.

Our work shows the numbers of young recruited each year and when they entered the population, how the numbers of adults of both sexes varied over the three years, and the differences that were present between the species in the ACT and that near Cooma, NSW. The data allow for expanding our understanding if any differences are present between these population parameters for these two species. The specific aims of the growth analyses were: (1) to determine whether asymptotic snout–vent lengths (SVLs) differed between T. lineata and T. osbornei; (2) to determine whether there was a difference in asymptotic SVL between males and females; and (3) to assess whether there were differences in growth rate and asymptotic length according to the location and year of hatching of each species. In addition, we examined how sexual dimorphism and reproductive activity, as indicated by changes in colouration, might differ between these species.

Materials and methods

Population structure and demographics

Throughout this study non-invasive techniques were applied in recognition of the conservation status of each species and their endangered natural temperate grassland habitat. Artificial arthropod burrows (plastic tubes) were used to capture lizards (Madani et al. 2023) from four locations organised in straight-line transects, 5 m apart and with 10 traps per transect. A flat metal roof (200 mm × 200 mm) placed 200 mm above each artificial burrow provided a protective shade. These roofed tubes were not traps and previous work has shown that they are significantly more effective in recapturing individual lizards than small pitfall traps (P < 0.001) and individuals were recaptured more often, permitting measurement of growth and other changes over time (Nelson et al. 1996). As night time refuges were unknown, tubes were checked during the day when lizards were more likely to be active. Two sites for studying T. lineata were near Canberra at elevations of approximately 590 m in the Jerrabomberra Valley (JV), and the Majura Valley (MV). The two locations used for T. osbornei were near Cooma: Kuma Nature Reserve (KNR) and Quartz Hill (QH), at 920 m and 990 m respectively, high elevations for lizards in Australia. Lizards were captured over a 3-year period commencing in November 1997. Tubes were checked at weekly to fortnightly intervals each season, except during the winter of 1998 when they were closed, and over the two other winter periods when they were checked at 3–6 weekly intervals. No checking occurred in June 1999.

Captured individuals were weighed (ISSCO Model 300 electronic balance ±0.01 g). SVL and tail length were measured using vernier callipers (±5 mm). The presences of preanal pores, ventral surface colouration, distinguishing features of individuals as well as indicators of breeding condition, were recorded. Adult males were distinguished by the presence of hemipenal swellings at the base of the tail and/or the presence of breeding colouration (Osborne et al. 1993). Enlargement of the testes in males and the presence of eggs felt during palpation of females were also used to distinguish sexes. Both males and females were recorded with preanal pores and this feature could not be used to discriminate sex as previously suggested by Osborne et al. (1993). The sex of smaller lizards without hemipenes (generally SVLs of <50 mm) could not be determined at the time of capture. Recaptures of these individuals after sexual maturity allowed subsequent determination of their sex. Captures and recaptures were photographed (Kodak Digital Camera 40). The unique back pattern of each lizard enabled recaptured individuals to be identified in the field from a photographic record of previous captures (Gould et al. 2023). A 5 mm mark was applied to the ventral surface of each lizard using a pen (Sharpie®) during processing to facilitate identification of recaptures. If lizards were not required for laboratory work, or other aspects of this study (Nelson and Cooper 2017), they were released within 1 m of capture immediately after processing.

Although the rate of checking between Canberra and Cooma sites was similar, the number of tubes at Canberra sites was approximately twice the number of tubes used at Cooma sites. Given this difference in effort between T. lineata and T. osbornei sites, and the variation in checking among some months, and between the first year compared with the second and third years, it was not possible to test whether capture rates differed among months, seasons and sites. There were also differences in habitat features (rocks, natural arthropod holes, density of tussocks, land use) among sites that may have influenced capture of lizards.

Reproductive colours

Lizards were assigned into one of 10 groups based on their neck and ventral surface colouration, and the intensity and combination of colours they displayed (Supplementary Table S1). Categories 8, 9, and 10 were combined for statistical analysis as there were few individuals and they all had bright orange flanks as well as yellow gulars.

These colour codes for individual lizards were divided into seasons, age class (adult, intermediate, and juvenile) and sex. For each individual captured each season within each year, the highest category of colouration was used for the analyses and replicate captures within seasons were disregarded.

In addition, the number of males with large hemipenes and/or testes was noted.

Statistical analyses

The data collected were analysed for differences among sexes, species, and years for first capture, growth rates and body condition. The methods for each analysis are described below.

No data were available regarding when lizards mature, although Smith (1994) and Langston (1996) recorded gravid females that were >50 mm from Canberra sites, and therefore adult. As growth rate generally decreases with increasing SVL in reptiles (Andrews 1982), captures were allocated into one of three categories: SVL < 40 mm, SVL ≥ 40 mm to <50 mm, and SVL ≥ 50 mm. These size categories correspond broadly to juveniles, intermediates, and adults and were based on data collected during T. lineata surveys near Canberra (Nelson et al. 1996, 1998a, 1998b) which demonstrated rapid early growth in SVL to approximately 40 mm, generally followed by a slowing of growth prior to asymptote at approximately 50 mm when sexes could be distinguished.

One of the most commonly used models for animal growth is the non-linear asymptotic regression model (Ratkowsky 1983). In this model, the length of the animal (Y) approaches an asymptote (α) as the animal ages (Eqn 1):

where t is the age of the animal, β is the size of the animal at birth (age 0), and γ is related to the animal’s growth rate. However, the age of each lizard is unknown and so an alternative growth parameter model (asymptotic regression with an offset) was used (Eqn 2),

where t is time (rather than age), α is the asymptote, β is related to the animal’s growth rate and γ is the time at which the size of the animal is zero.

The dates and SVL of capture were used to model growth. Capture dates were converted to days since first capture and by moving the origin to the date of first capture, the model was fitted separately for growth in each animal. The explanatory variable t becomes days since first capture, −γ becomes days between a hypothetical zero length and first capture, and α and β are unchanged. γ is necessary only because the age (time since hatching) of each animal is unknown.

In T. lineata and T. osbornei with a SVL of <50 mm, it was possible to distinguish males at a smaller length than in females. Thus, there was a potential for a sampling bias to small males in this group. Therefore, in the growth analyses, the following rules were applied: (1) if the maximum recorded SVL for an individual was ≥50 mm, and their sex was identified as either male or female, then previous captures of those individuals were identified as male or female respectively; (2) if the maximum recorded SVL was ≥50 mm, and the sex was not determined, then the individual was classified as female; (3) if the maximum recorded SVL was <50 mm, then the individual was classified as unidentified sex. Thus three ‘sexes’ were used: male, female and unidentified.

Non-linear mixed effects (nlme v. 3.1-150) models were then fitted (R v. 3.6.3) to estimate α, β and γ, and then to test for differences in α and β by site, sex and year. The mixed effects modelling ensured that observations from each animal were grouped (not treated as independent) and also allowed for animal-to-animal variation in α, β and γ (i.e. each parameter was treated as a random effect). Individual α and β parameters were assumed to have common means that vary with site, sex and year (i.e. were also treated as fixed effects). The date of hatching of each animal is still not known after fitting this model. The estimated date of zero length for each lizard comes from the γ estimate converted to a date. The mean size at hatching recorded for T. lineata was 24 mm (Langston 1996) and the time taken to grow from the hypothetical 0–24 mm is approximately 30 days under the model. Thus, the estimated biological year of hatching for each lizard in this analysis was given by the year corresponding to the date γ + 30 days.

Previous studies of T. lineata (Smith 1994; Langston 1996) recorded gravid females in populations from spring to mid-summer with hatching occurring from mid-summer through to autumn. This was followed by rapid growth to adult size before winter. Therefore, for the growth model, a biological ‘year’ was assumed to be from 1 July to 30 June. The model fitting proceeded using all combinations of sex, species (T. lineata and T. osbornei) and year of hatching (1997–1998, 1998–1999 and 1999–2000). Previous work indicated that at least three points of a growth curve were necessary for the best fit of individual growth curve (Nelson 2004) as long as those data were included with more points for other individuals, based on running several models with varying numbers of recaptures. An artefact of the modelling is potential for a negative correlation between SVL asymptote and growth rate. A significance level of 0.05 was used in all tests. Standard errors of differences between parameters, not standard errors of individual parameters, are presented as determined from the statistical models.

As the condition of wild-caught lizards was unknown, it was not possible to calculate the most appropriate body condition index for this species, and so log10(mass*10,000/SVL2) was used. Body condition typically varies with age of an animal and may depend on its life stage (e.g. growth versus reproduction). Therefore, for the body condition analyses, the lizards were again divided into three groups (juveniles, intermediates and adults) based on SVL, to allow for changes in body condition as an animal grows. The growth analyses showed adult SVL asymptote lengths of over 50 mm in the ACT. Therefore, in the condition analyses, a larger SVL was used as the cut off for the adult group to avoid large intermediates from being included in that group. The three size categories selected were: juveniles <40 mm, intermediates ≥40 mm to <55 mm, and adults ≥55 mm and the data sets for each were modelled separately. Sex was determined using the same characteristics and rules described above for the growth analyses. Species (T. lineata or T. osbornei) was used in these analyses that aimed to determine whether the body condition index varied with sex, species, season and year of observation. Linear mixed models were used with animal as a random effect and sex, season, and year as fixed effects. Because of low numbers of juvenile animals relative to the number of categories in sex * species * season + year, there were no animals in some categories. The juvenile analysis was therefore restricted: sex did not include males and was confined to females and individuals of unidentified sex, and winter and spring were not included in season.

Juvenile and intermediate unidentified sex animals may be non-survivors or dispersing animals as they had few recaptures and were not captured at ≥50 mm SVL. Thus, their sex could not be determined from subsequent captures at larger SVLs. As non-recaptures/non-survivors/dispersers, they may be behaving differently from lizards that were subsequently captured at ≥50 mm SVL. The males and females captured at ≥50 mm SVL at each site were grouped together and classed as recaptures. For the analyses on intermediates, recaptures were grouped separately from non-recaptures (non-survivors or dispersers) and this term was added to the full model, and sex was deleted as all non-recaptures were of unknown sex. Predicted means of condition indices are shown with standard error of differences (SEDs). A significance level of 0.05 was used.

Results

Season refers to three-monthly calendar periods with austral spring defined as September, October and November, followed by summer, autumn and winter.

Population structure

The number of T. lineata captured at the Canberra sites (where survey effort was double) was approximately twice the number of T. osbornei captured at the Cooma sites (Table 1). Proportions of known females, males and unidentified individuals captured in the two regions were similar. However, the proportion of female lizards is likely to be underestimated, as they were more difficult to distinguish, compared with males, and thus females were more likely to be placed in the unidentified sex category.

| Sex\species | T. lineate (n) | T. lineate (%) | T. osbornei (n) | T. osbornei (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | 49 | 28 | 24 | 27 | |

| Males | 71 | 41 | 47 | 53 | |

| Unidentified | 54 | 31 | 18 | 20 | |

| Totals | 174 | 100 | 89 | 100 |

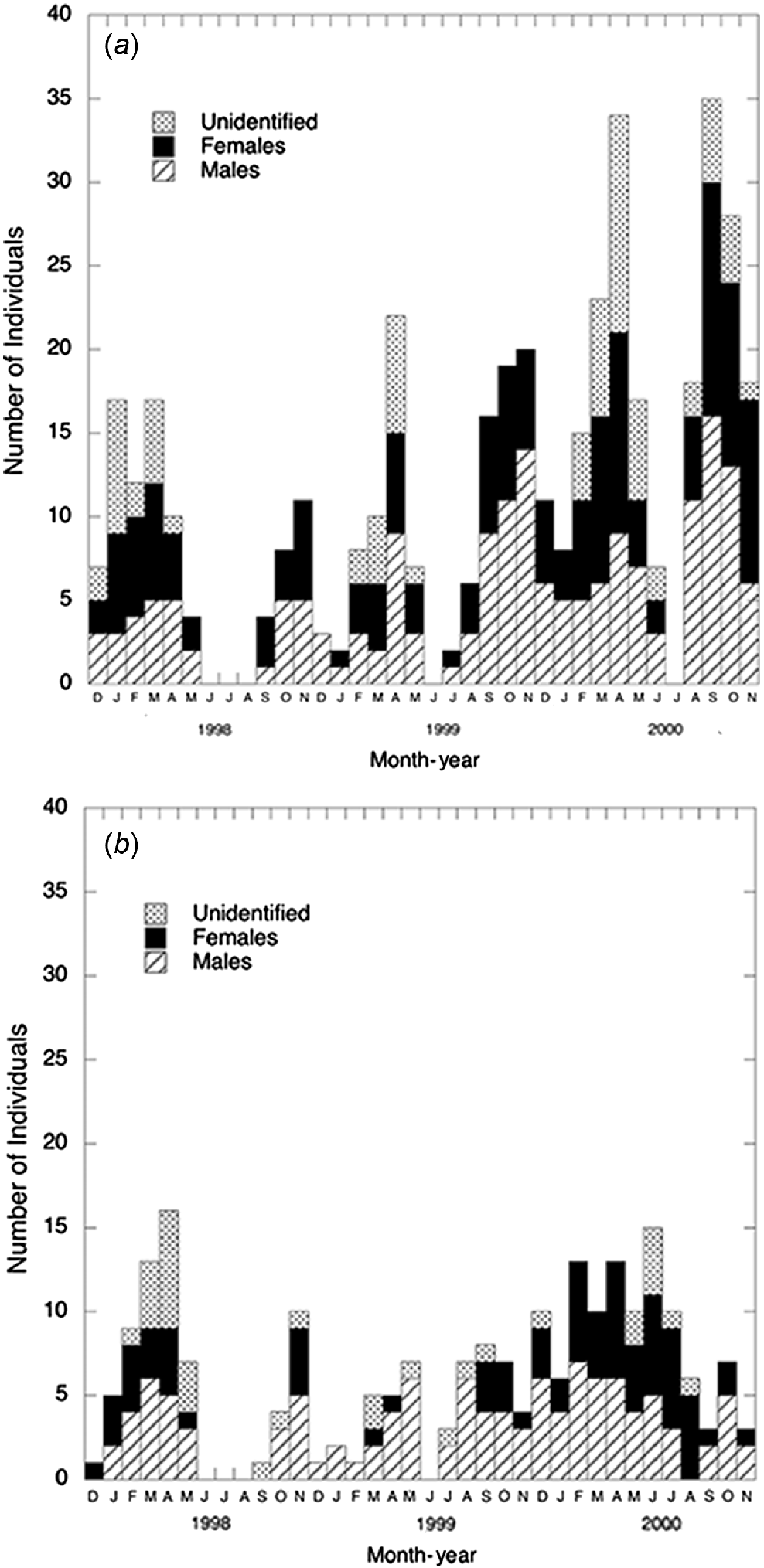

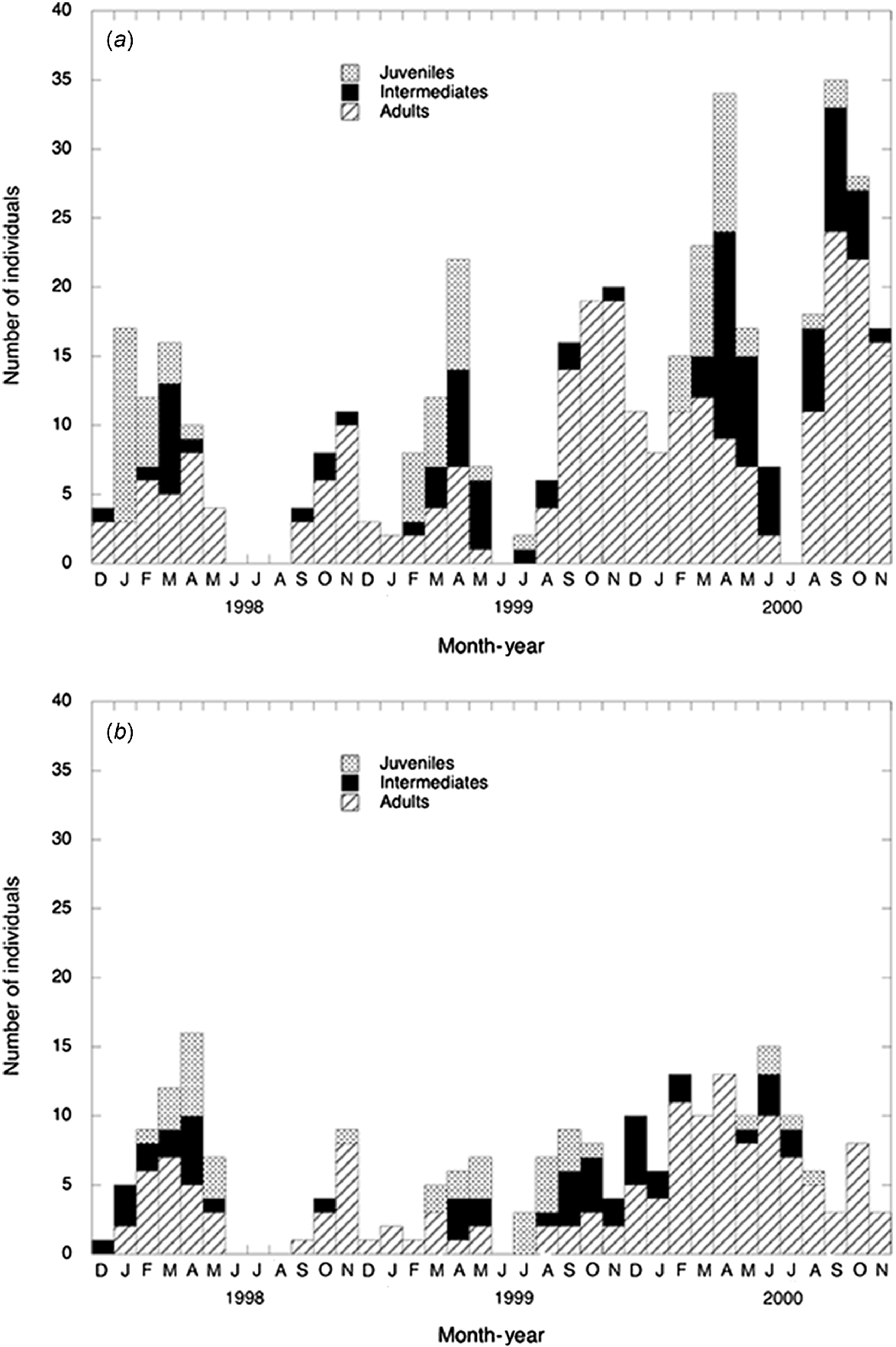

The numbers of individual adults, intermediates and juveniles of the two species captured each month are shown (Fig. 1). If an individual was captured more than once in a month, the size category at the first capture was used. Adults (≥50 mm) were present every month that captures occurred, except for December 1997 at Cooma and July 1999 at both Canberra and Cooma. Juveniles were detected at least one month later in the T. osbornei populations. In 1998, T. lineata juveniles were captured during January but not until February in 1999 and 2000. Juveniles of T. osbornei were not caught at Cooma until February 1998, March 1999 and May 2000. Juveniles were still present in those populations in November 1998, October 1999 and August 2000, and T. lineata juveniles only were captured in October 2000. Only one intermediate lizard was detected at the beginning of summer (December 1997) in the T. lineata populations during the 3-year period whereas intermediates were present in the T. osbornei populations throughout summer in 1997–1998 and 1999–2000.

Monthly captures of individual juvenile, intermediate and adult (a) Tympanocryptis lineata from Canberra and (b) T. osbornei from Cooma populations from December 1997 to November 2000.

Numbers of male, female and unknown sex individuals captured are shown (Fig. 2). Males and females of both species were captured throughout the year. No adult T. lineata females were captured in December 1998 and May 1999 whereas females of T. osbornei generally formed a small proportion of the adult captures from September 1998 to August 1999.

Linear growth and longevity

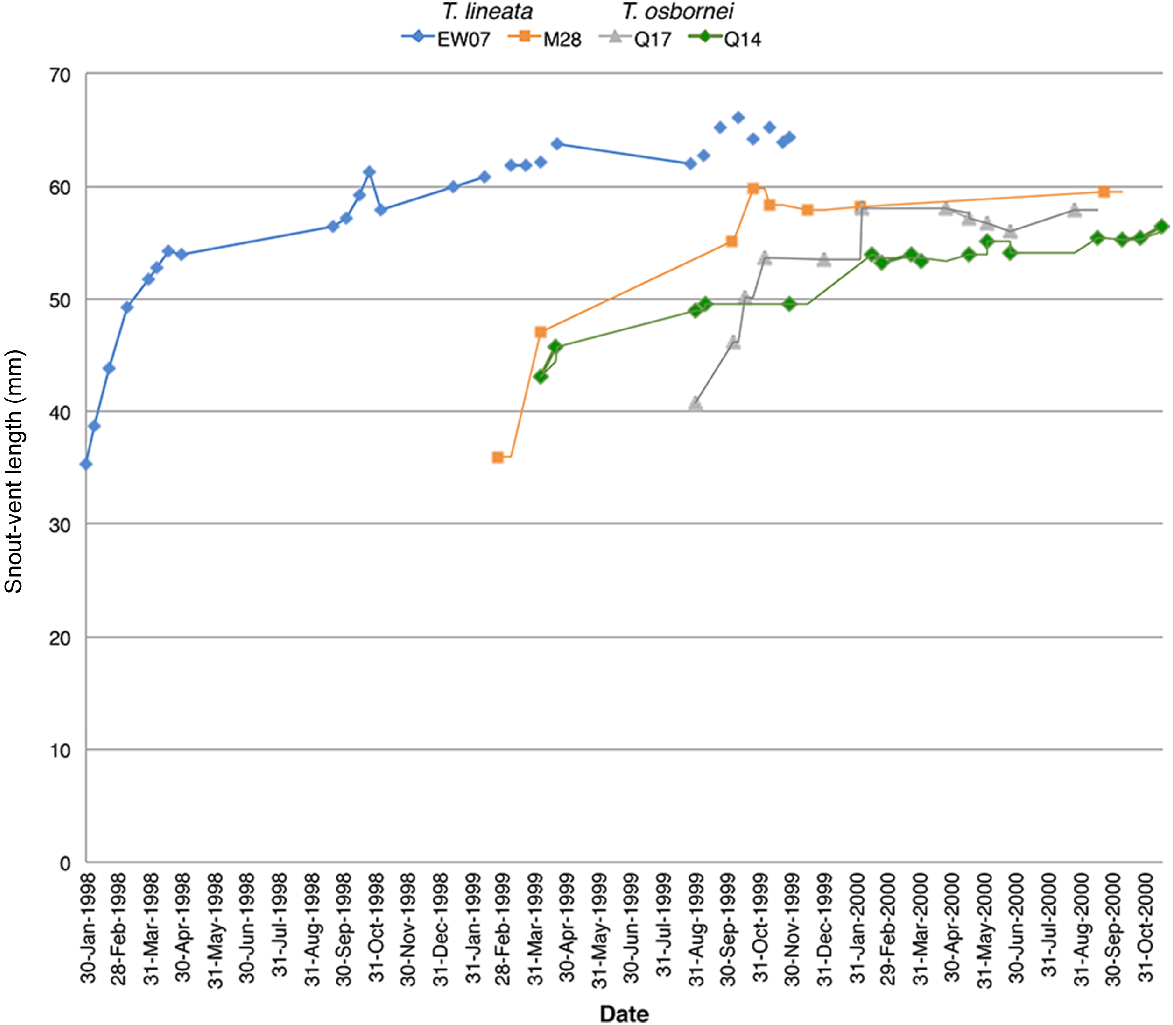

Increase in SVL and longevity of two individuals of each species that were captured more than once during this study indicate that both individuals of both species can survive well beyond a year (Fig. 3). Comparison of longevity of the sexes as indicated by recaptures suggests that in T. lineata, more females appeared to survive into a second year than do males (Supplementary Fig. S1 and Table 2). Most T. osbornei females were captured either when they were adults, or almost at the SVL asymptote, and continued to be recaptured for several months into their second year (Table 2 and Fig. S1). Male T. osbornei also survived into a second year (Table 2), and one male (K03), survived into his third year (Fig. S1).

Males and females of both species can live for more than one year as shown by repeated trapping. T. lineata female (EW07) captured from East Woden and male (M28) captured from Majura Field Firing Range in the A.C.T. both T. osbornei female (Q17) and male (Q14) were captured at Quartz Hill, N.S.W. The small decreases in SVL are within measurement error of the method.

| T. lineata | Mean no. of days (±s.d.) | T. osbornei | Mean no. of days (±s.d.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 6 (1) | 616 ± 163.0 | 1 | 360 | |

| Male | 5 (1) | 503 ± 138.8 | 4 (1) | 629 ± 127.4 |

Numbers in parentheses are ones that survived more than 700 days.

Each lizard had a different growth pattern, but for individuals captured as juveniles or intermediates there appeared to be rapid early SVL growth, slowing towards an asymptote, although this trend was less clear in T. osbornei for all years, and for both species during 2000. Growth in immature lizards either slowed or was negligible during winter (Figs 3 and S1). Early growth curves for animals that were not captured at adult size (SVL ≥ 50 mm) during the three years of fieldwork, and whose sex could not be determined showed this seasonal response (Fig. S1a–d).

For growth rate, the model found no differences between species, sex or year. The model indicates rapid growth of SVL in all hatchlings of both species (Fig. 4), although the model is based upon animals that are already moving on the surface. For asymptotic length, highly significant effects of sex (F1497 = 336.43, P < 0.001) were identified in the model, although the deviation may be relatively late in growth (Fig. 4). A simplified general mean growth model for all females and males of both species is:

where Y is the SVL of the animal and t is its age in days after first capture. The relationship between age in days and SVL (mm) from a hypothetical zero length can be calculated by obtaining.

Mean SVL asymptote lengths derived from the model show that females were 5.1 mm longer than males (Table 3, P < 0.001). Although the mean between sexes differed, there was no significant difference in mean asymptotic SVL of T. lineata compared with asymptotic SVL of T. osbornei (Table S2).

Fitted growth curve for both Tympanocryptis species showing one female and one male of south-eastern Australia. Figure drawn assuming that curve passes through zero on the x- and y-axes and shows approximate 5 mm difference in male and female at the asymptote. Notice that number of days to reach asymptotic SVL is slightly different in male and female lizards according to the model.

| Species | Sex | Mean | Standard error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. lineata | ||||

| F | 56.8a | 1.24 | ||

| M | 51.7b | 1.98 | ||

| T. osbornei | ||||

| F | 56.8a | 1.24 | ||

| M | 51.7b | 1.98 | ||

Significant differences are at P < 0.05 (d.f. = 409). Groups with the same letter are not significantly different.

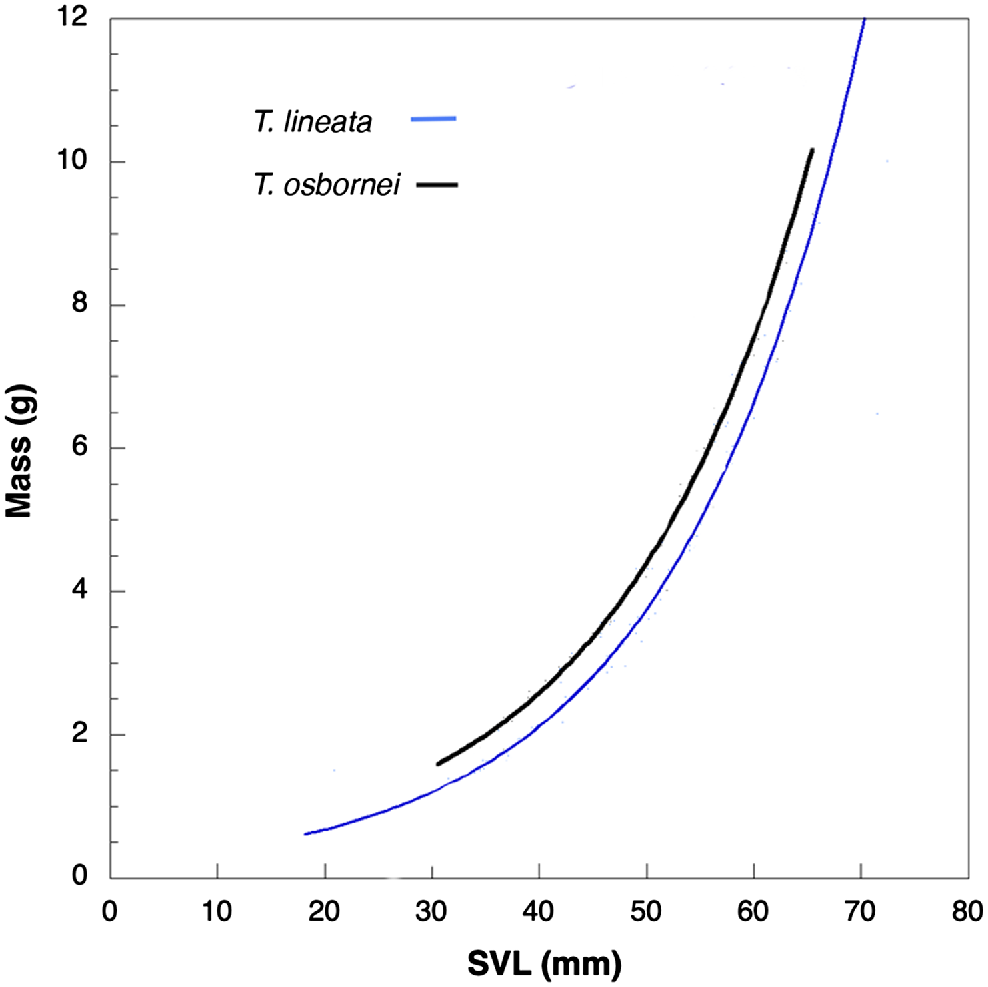

Body condition

The non-transformed mass: SVL data showed the same trend for both T. lineata and T. osbornei, with the smallest ratio exhibited by juveniles and increasing as the lizards’ SVL increased (Fig. 5). These data also demonstrate that the range in SVLs of T. lineata was greater than for T. osbornei as the values are more compressed on the x-axis for the latter species.

Fitted non-transformed body condition curves (body mass plotted against SVL) showing exponential change of mass as SVL increases for both species. Figure shows difference in mass for same SVL. Exponential curve fitted to data (T. lineata mass = 0.213 * e0.057 * SVL; T. osbornei mass = 0.256 * e0.056 * SVL) (n = 371).

‘Predicted mean condition indices’ presented are derived values from the fitted models and hereafter will be referred to as ‘mean condition indices’. The juvenile condition index model demonstrated that only species was significant (n = 131, Wald test, χ21 = 19.69, P < 0.001). The mean condition index for T. osbornei juveniles (1.167) was significantly higher than that of T. lineata juveniles (1.084, s.e.d. = 0.019). No sex or seasonal effects were found for this size class.

Differences in mean condition index between intermediate-sized lizards were also significant (n = 371, Wald test, χ21 = 43.12, P < 0.001) (Table S3), with T. osbornei having significantly higher indices. Intermediate-sized lizards that were eventually recaptured as adults had significantly higher mean condition indices than single-captured lizards (Table S3) (n = 371, Wald test, χ21 = 21.54, P < 0.001). However, there were significant interaction terms for both species * season (Wald test, χ23 = 9.08, P = 0.028), and species * season * recapture (Wald test, χ23 = 14.56, P = 0.002).

A significant difference among years was also demonstrated by the intermediate condition index model (n = 371, Wald test, χ23 = 29.91, P < 0.001) with intermediate-sized lizards captured in 1997–1998 having significantly higher mean condition indices than in any other year, and 1998–1999 higher than in 1999–2000.

Sex accounted for most of the difference in the adult lizard body condition index model (n = 364, Wald test, χ21 = 36.61, P < 0.001) (Table S4). Other significant variables in this model were season (Wald test, χ23 = 11.65, P = 0.009) and species (Wald test, χ21 = 4.19, P = 0.041). The model also identified significant season * sex (Wald test, χ23 = 26.18, P < 0.001) and season * species (Wald test, χ23 = 8.09, P = 0.044) interactions.

The adult seasonal mean condition indices predicted from this model show that adult T. osbornei populations had significantly higher mean condition indices than T. lineata adults (Fig. 5), although the same seasonal trends are present. Female mean condition indices were significantly higher in spring compared with summer and winter. In autumn, male mean condition indices were significantly higher than spring and summer but there was no difference among winter, spring and summer. Finally, compared with males, adult females displayed significantly higher mean condition indices during spring and summer.

Reproductive colours

The numbers of lizards of each species with colours are shown for each season with colour rankings only between 2 and 10 (Table S5) and the age categories (Table S6). The main effects of species (F[1142] = 10.0, P = 0.002), season (F[3157] = 6.6, P = 0.0003) and sex (F[1170] = 16.0, P < 0.0001) were all significant predictors of reproductive colours. In addition, the interaction of sex * season is significant (F[3159] = 4.9, P = 0.003) indicating that the two sexes change colours differently depending upon season. Males of both species do not show a large change in colour from autumn to spring but do display prominent testes and/or hemipenes in autumn and spring (Table S7). Females of both species appear to have much higher colouration values in spring and autumn than in summer and winter (Table 4).

| Season | Sex | T. lineata | T. osbornei | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autumn | F | 3.7 ± 0.33 | 2.8 ± 0.39 | |

| Winter | F | 2.2 ± 0.56 | 1.3 ± 0.59 | |

| Spring | F | 3.4 ± 0.30 | 2.5 ± 0.38 | |

| Summer | F | 1.9 ± 0.44 | 1.1 ± 0.46 | |

| Autumn | M | 3.8 ± 0.25 | 3.0 ± 0.25 | |

| Winter | M | 3.6 ± 0.35 | 2.7 ± 0.36 | |

| Spring | M | 4.6 ± 0.23 | 3.7 ± 0.28 | |

| Summer | M | 4.1 ± 0.29 | 3.2 ± 0.31 |

Discussion

Populations of T. lineata and T. osbornei showed the same general annual trends in captures of adults, intermediates and juveniles, although there was slight variation among years and recruitment was detected at least a month later for T. osbornei. Males in both species were predicted to be shorter in SVL than females.

Population structure

The capture data suggest that the population structure in terms of sex did not differ between the two species. The same general trends in monthly captures for the two species (Figs 1 and 2) suggest that the closely related species have similar life cycles. The weather patterns experienced at Canberra and Cooma during this study may explain some of the trends observed (Nelson and Cooper 2017). For example, the low numbers of lizards using artificial burrows in the summer, prior to the appearance of hatchlings, may be influenced by higher minimum temperatures at this time of the year (Bureau of Meteorology 1996–2003), allowing lizards to use alternative refuges such as tussocks when the temperatures of these refuges do not drop as low as during colder months (Nelson and Cooper 2017).

During other seasons when lizards are active they may be forced to escape cold night temperatures by using the insulative qualities of natural holes and artificial tubes 14 cm below the ground surface (Nelson and Cooper 2017). Seasonal variation in the use of refuge sites in response to thermal conditions has been reported in other lizards (Christian et al. 1984) and in the field Tympanocryptis populations have a range of alternative sources of shelter from which to select. These refuges include tussocks of various densities, under rocks, and arthropod holes (McGrath et al. 2015; Nelson and Cooper 2017).

Lower captures may also reflect reduced relative activity of lizards during periods of temperature extremes (Nelson and Cooper 2017), or during periods of vulnerability, such as when moulting or, in the case of adult females, while eggs are calcifying within their bodies. Gravid T. lineata females may be less active in summer prior to oviposition when a large clutch mass (estimated to represent 49% of their total body mass: Langston 1996) would inhibit mobility and increase vulnerability to predation (Shine 1980; Ballinger and Congdon 1981; Heatwole and Taylor 1987). Alternative refuges to the hard-sided arthropod tubes, such as tussocks and areas under rocks (where available), may provide more space for females when distended with eggs (Duffield and Bull 1996). More research on gravid T. lineata or T. osbornei is required to test these suggestions.

The range of hatching times in the two species is not known in the field, but the differences recorded in captures between these species, and among years, may be related to variation in weather patterns. For example, late summer and autumn is the main period of recruitment and growth in the two species, as demonstrated by the three age classes of lizards generally present during this period (Fig. 1). This pattern coincides with the warmest period of the year which is consistent with breeding in other southern Australian reptiles (Shine 1995) and when an abundance of invertebrate food materials was observed in the field (Melbourne 1993; Nelson 2004). This timing therefore provides hatchlings with the maximum opportunity to be active, feed, grow and accumulate mass prior to winter (Adolph and Porter 1996). However, during the three years of fieldwork, the capture of hatchling lizards commenced at different times over summer and autumn. The El Nino drought conditions experienced during the spring and summer of 1997–1998 provided warm temperatures, low rainfall and therefore less cloud (Bureau of Meteorology 1996–2003), sparse vegetation cover and warmer soil, that may facilitate basking for gravid females, and thus oviductal egg development, and hastened embryogenesis during egg incubation following oviposition (Van Damme et al. 1992; Shine and Harlow 1996). Thus in 1998 hatchlings of T. lineata were captured as early as January and SVLs of >40 mm were achieved by some lizards by February when the first hatchlings of T. osbornei were collected.

Possible explanations for the 1-month delay in recruitment for T. osbornei during 1998 and 1999, compared with T. lineata, may include the longer duration of lower minimum temperatures experienced in that region of NSW (Nelson and Cooper 2017). Skin chest temperatures of T. osbornei were lower than in T. lineata in autumn, especially in the afternoon (Nelson and Cooper 2017). Lower temperatures have been linked to delayed hatching of other lizards (Van Damme et al. 1992; Qualls and Shine 1998), and recruitment delays of approximately one month have been observed in populations of other temperate zone lizard species inhabiting higher elevations (Wapstra et al. 1999) or colder sites (Mathies and Andrews 1995). A second explanation for the delayed recruitment in T. osbornei may be increased size at hatching, which would provide a selective advantage in colder conditions. Only one T. osbornei juvenile was less than 30 mm in SVL, whereas many captured T. lineata were below this length (Fig. S1). Cooler temperatures may result in increased SVL in hatching young (Atkinson 1996) and larger offspring in populations from colder environments have been reported in other lizard species with a wide geographic range (Forsman and Shine 1995; Mathies and Andrews 1995; Rohr 1997; Qualls and Shine 1998) to allow longer egg retention (Mathies and Andrews 1995). Further research is needed to identify whether any of these alternatives occur in the cooler conditions where T. osbornei occurs.

Longevity

This study demonstrates that both species can survive beyond two years in the field, and thus longer than the maximum age of 22 months previously recorded for T. lineata (Langston 1996). Some lizards may survive through only one breeding period, but others may have two clutches surviving through the following breeding period. Survivorship in both species would be particularly vulnerable to stochastic events that affected females prior to oviposition, and events that harmed eggs during incubation. With the exception of one male T. osbornei, no lizards survived beyond three years, which is considerably less than a record for captive T. lineata (Anonymous 2023). Our observations suggest that longevity in the field may be affected by stochastic factors which may include food availability, predators (Ballinger 1979), environmental temperatures (Wapstra et al. 2001) and reproduction as reproductive effort can affect post-reproductive survivorship (Bauwens and Diaz-Uriarte 1997). Further study is necessary to determine the relative importance of each of these variables on longevity.

Growth

The combined species growth model shows rapid growth of hatchlings from all sites (Fig. 4), which is typical of reptilian growth patterns (Andrews 1982), and is consistent with previous observations (Smith 1994; Langston 1996). The longer the time between hatching and the onset of cooler winter temperatures, the larger the animals can grow in SVL and accumulate mass. Presumably, the larger a lizard is, the better it can survive winter conditions when it becomes less active (brumation) (Nelson and Cooper 2017) and relies on energy storage (Sinervo and Adolph 1989). Adults of both species were active during the winter, usually on warmer days (Robertson and Cooper 2000; Nelson 2004; Nelson and Cooper 2017), likely in order to feed, but the slow growth of juveniles during this period suggests that they remain inactive, presumably as food availability is limited. Hatchling growth rate may vary between species but size at hatching needs to be included in the model (Nelson 2004).

If asymptote in SVL represents maturity in both species, males are likely to reach maturity earlier than females from the same cohort because, in all populations examined, males are shorter than females. Males would also be ready to mate with late maturing females from their cohort if these females reached maturity in spring. Autumn is at the end of the period of warmer weather when conditions were more conducive for activity and feeding, and when males may have maximised food intake prior to mating (Brown 1988). As mean condition indices of adult males in both species are significantly higher in autumn than in spring and summer, an autumn mating strategy would optimise mating when the males are in their best condition and provide an insurance against a harsh winter that may lead to higher mortality.

Body condition

The higher mean condition indices for juvenile, intermediate and adult T. osbornei may be a phenotypic response to colder minimum temperatures at Cooma and a longer period of winter conditions (Bureau of Meteorology 1996–2003). This is consistent with Mitchell’s (1948) suggestion of a build-up of fat bodies for survival over long winters, with the response appearing to be more pronounced at Cooma sites. Accumulation of mass relative to SVL has been described in other lizards subjected to short growing seasons and lengthy winters (e.g. Sinervo and Adolph 1989). Tsuji (1988) stated that higher relative body mass in lizards from a cooler and more variable thermal environment may be insurance from seasonal and yearly variability in energy availability. Mitchell (1948) suggested that diet may play a role in accumulating fat bodies in colder areas and the quality and quantity of food at higher altitudes for T. osbornei each season therefore warrants further investigation.

The absence of a seasonal effect on mean condition indices of intermediates that were recaptured as adults at both Canberra and Cooma sites was unexpected, especially given the variability in the thermal environments in both regions (Nelson and Cooper 2017). It therefore appears that intermediate-sized lizards that are recaptured as adults are successful at obtaining resources and maintaining their energy requirements throughout the year, which may explain their apparent survival success. Remaining inactive at low body temperatures (Nelson and Cooper 2017) and thus not metabolising stored fat (Congdon et al. 1982) would assist T. osbornei lizards in maintaining condition. Dietary and field metabolic rate studies are needed to determine if there are differences between these species among seasons.

A number of factors could moderate mean condition indices of adult females among autumn, winter and summer, and for adult males in winter, spring and summer. For example, if lizards approached winter in reasonable condition, and then became inactive while tolerating low body temperatures (Nelson and Cooper 2017) individuals may be able to reduce energy expenditure (Bennett and Nagy 1977; Congdon et al. 1982; Tsuji 1988), and thus limit loss of condition over this period, despite not feeding. Comparison of body temperatures in the two different locations suggested that activity was reduced to periods when body temperatures could be maintained within the preferred body temperature range (Nelson and Cooper 2017) and that refuges were sought once temperature caused body temperatures to increase outside that range.

As season and sex are closely linked to reproductive processes, it is not surprising that both species had similar responses in their mean condition index. The coordination of reproductive activity with seasons to maximise development of oviductal eggs, embryogenesis and hatchling growth is particularly important in a short-lived lizard species (Dunham and Overall 1994) that has a low reproductive output (Langston 1996) and survives in a temperate environment with high variability in temperatures among seasons.

Colouration

Colour patterns and development of enlarged hemipenes suggests that mating may occur twice during the year, in spring and again in autumn. This pattern of reproduction may lead to direct development of spring eggs into hatchlings in early summer, but the eggs produced in autumn are either laid and remain in refuges until spring, or are held in the female during brumation. Without further work we cannot determine whether females lay or retain eggs, but the recruitment patterns suggest only one period of young emergence, so if autumn mating occurs, the eggs produced are not associated with young emergence. However, as colouration and increased hemipenes are enhanced in both spring and autumn, any reduction in activity in summer would not limit the most important reproductive processes of these lizards, as previously suggested (Doucette et al. 2023)

Summary

Two species of Tympanocryptis are compared and appear to display considerable seasonal and annual variability in population structure, and phenotypic plasticity in life history traits. Data suggest that there is only one period of recruitment in both species in the field, which generally commences in summer or early autumn, although it can extend across several months. There is a relatively short period for hatchlings to grow rapidly and mature prior to winter, and this window is narrower for T. osbornei. Therefore, if oviposition occurs late in the season and/or embryogenesis or post-hatching growth are delayed, then breeding and recruitment may be compromised, including in the following year. If the SVL asymptote corresponds with sexual maturity, lizards may be in a better position to reproduce within their first year, and if food is not a limiting factor they can direct more resources into accumulation of mass that may be important for insulation during longer winters.

Data availability

Data are available by request to the second author through the Data Commons at the Australian National University.

Declaration of funding

No specific funding was given for this work, although LN was supported by her employers, ACT Government and New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service. Her work was also supported by the PhD funds from the Australian National University and CSIRO Wildlife through the collaborative student research grant program.

Ethical approval

The research was undertaken under ethics approval by ANU animal experimentation ethics committee (applications F.BTZ.61.96, F.BTZ.90.98 and F.BTZ.38.01). Work in the ACT was covered by licences from ACT Parks and Conservation (Licence nos LT1996050, LT1997001, LI1997105, LE1997066, LT1998006, LI1998063, LE1998032, LT1999004, LI1999025, LE1999018, LT2000004, LI2000007, LE2000004) and in NSW by licence from Department of Environment and Climate Change (now Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water) (Licence no. A2254).

Acknowledgements

We thank Ross Cunningham, Christine Donnelley, Ann Cowling (ANU Statistical Consulting Unit) and Terri Neeman (Biological Data Science Institute) for help with the statistics. The work could not have been done without access to lands on which the lizards lived, so thank you to the various landowners in NSW and land lessees in the ACT. The Australian Army and New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service also were kind to allow access to the lands they manage. This paper forms part of the PhD thesis of Nelson (2004).

References

Adolph SC, Porter WP (1993) Temperature, activity, and lizard life histories. The American Naturalist 142(2), 273-295.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Adolph SC, Porter WP (1996) Growth, seasonality, and lizard life histories: age and size at maturity. Oikos 77(2), 267-278.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ballinger RE (1979) Intraspecific variation in demography and life history of the lizard, Sceloporus jarrovi, along an altitudinal gradient in southeastern Arizona. Ecology 60(5), 901-909.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ballinger RE, Congdon JD (1981) Population ecology and life history strategy of a montane lizard (Sceloporus scalaris) in southeastern Arizona. Journal of Natural History 15(2), 213-222.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bauwens D, Diaz-Uriarte R (1997) Covariation of life-history traits in lacertid lizards: a comparative study. The American Naturalist 149(1), 91-111.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bennett AF, Nagy KA (1977) Energy expenditure in free-ranging lizards. Ecology 58(3), 697-700.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Brown G (1988) The diet of Leiolopisma entrecasteauxii (Lacertilia, Scincidae) from southwestern Victoria, with notes on its relationship with the reproductive-cycle. Australian Wildlife Research 15(6), 605-614.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bureau of Meteorology (1996–2003) Climate data online. Commonwealth of Australia. Available at http://bom.gov.au/climate/data/ [accessed 15 January 2025]

Christian KA, Tracy CR, Porter WP (1984) Physiological and ecological consequences of sleeping-site selection by the Galapagos land iguana (Conolophus pallidus). Ecology 65(3), 752-758.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Doucette LI, Duncan RP, Osborne WS, Evans M, Georges A, Gruber B, Sarre SD (2023) Climate warming drives a temperate-zone lizard to its upper thermal limits, restricting activity, and increasing energetic costs. Scientific Reports 13, 9603.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Duffield GA, Bull CM (1996) Characteristics of the litter of the gidgee skink, Egernia stokesii. Wildlife Research 23(3), 337-341.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dunham AE, Overall KL (1994) Population responses to environmental change: life history variation, individual-based models, and the population dynamics of short-lived organisms. American Zoologist 34(3), 382-396.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Forsman A, Shine R (1995) Parallel geographic variation in body shape and reproductive life history within the Australian scincid lizard Lampropholis delicata. Functional Ecology 9(6), 818-828.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gould J, Beranek C, Madani G (2023) Dragon detectives: citizen science confirms photo-ID as an effective tool for monitoring an endangered reptile. Wildlife Research 51, WR23036.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Madani G, Pietsch R, Beranek C (2023) Where are my dragons? Replicating refugia to enhance the detection probability of an endangered cryptic reptile. Acta Oecologica 119, 103910.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mathies T, Andrews RM (1995) Thermal and reproductive biology of high and low elevation populations of the lizard Sceloporus scalaris: implications for the evolution of viviparity. Oecologia 104, 101-111.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McGrath T, Guillera-Arroita G, Lahoz-Monfort JJ, Osborne W, Hunter D, Sarre SD (2015) Accounting for detectability when surveying for rare or declining reptiles: Turning rocks to find the grassland earless dragon in Australia. Biological Conservation 182, 53-62.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Melville J, Goebel S, Starr C, Keogh JS, Austin JJ (2007) Conservation genetics and species status of an endangered Australian dragon, Tympanocryptis pinguicolla (Reptilia: Agamidae). Conservation Genetics 8, 185-195.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Melville J, Chaplin K, Hutchinson M, Sumner J, Gruber B, MacDonald AJ, Sarre SD (2019) Taxonomy and conservation of grassland earless dragons: new species and an assessment of the first possible extinction of a reptile on mainland Australia. Royal Society Open Science 6(5), 190233.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Mitchell FJ (1948) A revision of the lacertilian genus Tympanocryptis. Records of the South Australian Museum 9, 57-86.

| Google Scholar |

Nelson LS, Cooper PD (2017) Seasonal effects on body temperature of the endangered grassland earless dragon, Tympanocryptis pinguicolla, from populations at two elevations. Australian Journal of Zoology 65(3), 165-178.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Osborne WS, Kukolic K, Davis MS, Blackburn R (1993) Recent records of the earless dragon Tympanocryptis lineata pinguicolla in the Canberra region and a description of its habitat. Herpetofauna 23, 16-25.

| Google Scholar |

Qualls FJ, Shine R (1998) Geographic variation in lizard phenotypes: importance of the incubation environment. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 64(4), 477-491.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rohr DH (1997) Demographic and life-history variation in two proximate populations of a viviparous skink separated by a steep altitudinal gradient. Journal of Animal Ecology 66(4), 567-578.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Scott IAW, Keogh JS (2000) Conservation genetics of the endangered grassland earless dragon Tympanocryptis pinguicolla (Reptilia: Agamidae) in southeastern Australia. Conservation Genetics 1, 357-363.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Shine R (1980) “Costs” of reproduction in reptiles. Oecologia 46, 92-100.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Shine R (1995) A new hypothesis for the evolution of viviparity in reptiles. The American Naturalist 145, 809-823.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Shine R, Harlow PS (1996) Maternal manipulation of offspring phenotypes via nest-site selection in an oviparous lizard. Ecology 77(6), 1808-1817.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sinervo B, Adolph SC (1989) Thermal sensitivity of growth rate in hatchling Sceloporus lizards: environmental, behavioral and genetic aspects. Oecologia 78, 411-419.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Smith WJS, Osborne WS, Donnellan SC, Cooper PD (1999) The systematic status of earless dragon lizards, Tympanocryptis (Reptilia: Agamidae), in south-eastern Australia. Australian Journal of Zoology 47(6), 551-564.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Stevens TA, Evans MC, Osborne WS, Sarre SD (2010) Home ranges of, and habitat use by, the grassland earless dragon (Tympanocryptis pinguicolla) in remnant native grasslands near Canberra. Australian Journal of Zoology 58(2), 76-84.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tsuji JS (1988) Thermal acclimation of metabolism in Sceloporus lizards from different Latitudes. Physiological Zoology 61(3), 241-253.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Van Damme R, Bauwens D, Braña F, Verheyen RF (1992) Incubation temperature differentially affects hatching time, egg survival and sprint speed in the lizard Podarcis muralis. Herpetologica 48(2), 220-228.

| Google Scholar |

Wapstra E, Swain R, Jones SM, O’Reilly J (1999) Geographical and annual variation in reproductive cycles in the Tasmanian spotted snow skink, Niveoscincus ocellantus (Squamata: Scincidae). Australian Journal of Zoology 47(6), 539-550.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wapstra E, Swain R, O’Reilly J (2001) Geographic variation in age and size maturity in a small Australian viviparous skink. Copeia 2001(3), 646-655.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |