Ecological history can inform current conservation actions: lessons from an Australian rodent

Peter Menkhorst A B C *

A B C *

A

B

C

Abstract

Many Australian terrestrial mammal species occupy relictual distributions that represent only a small proportion of their original distribution and habitat breadth.

To illustrate how examination of the historical records of a taxon, and their interpretation in an ecological context, can benefit conservation programs by counteracting the pervasive effects of generational memory loss (recency bias) and shifting baselines.

Historical records including recent detailed mapping of the routes used by two European exploration parties in the mid-19th century, were used to investigate and interpret the localities and environments previously occupied by Mitchell’s Hopping Mouse (Notomys mitchellii).

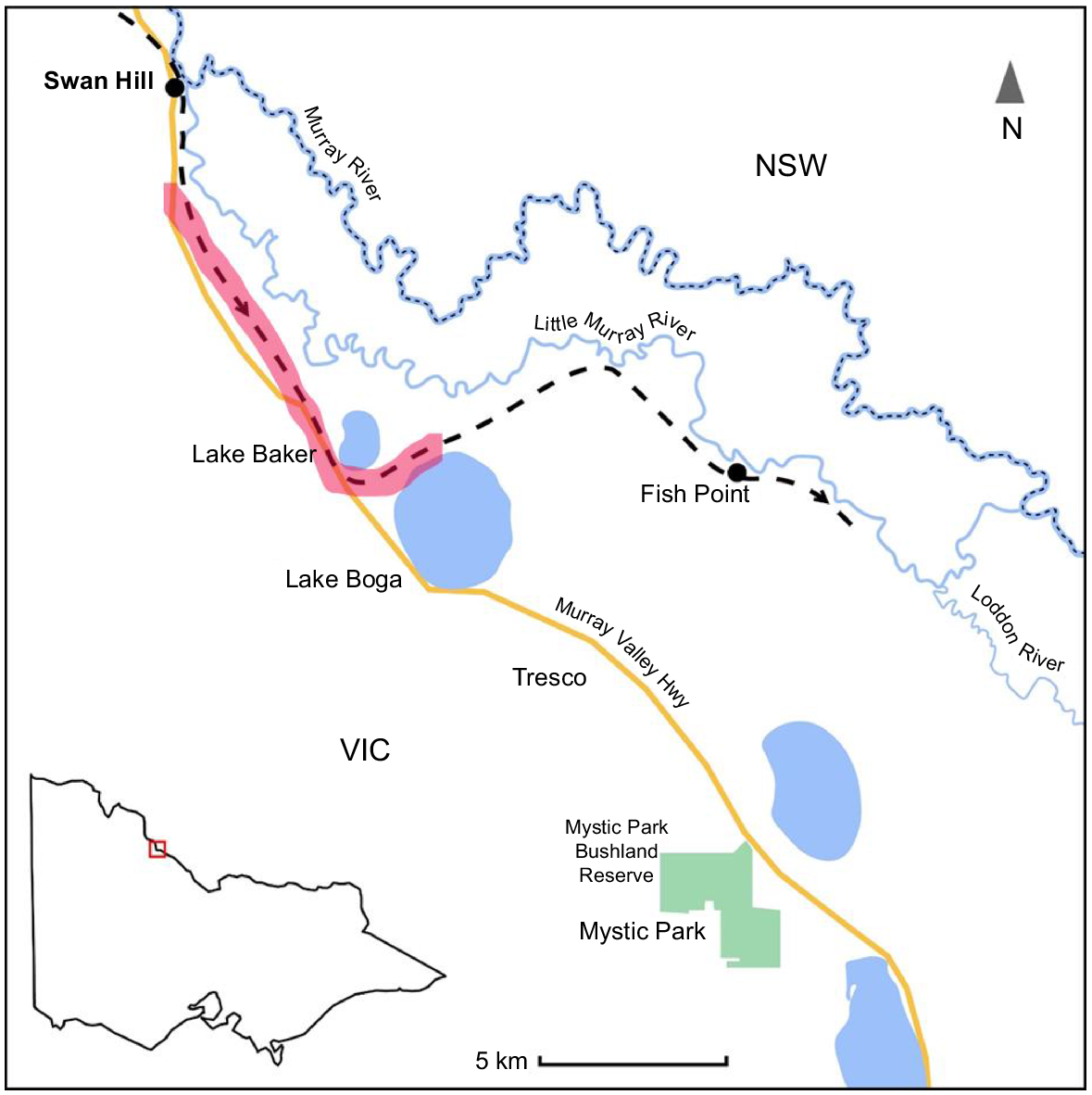

In south-eastern Australia, the current realised niche of Mitchell’s Hopping Mouse is a subset of the historical niche occupied in the mid-1800s. It formerly occurred in two bioregions and four sub-regions that are currently not known to support the species. Understanding these contractions is important in developing the full range of conservation strategies for the species.

This case study provides a valuable example of the potential effects of recency bias; for example, the tendency to focus conservation actions within the current realised niche and neglect consideration of other potential sites and habitats. Not recognising such distortions may restrict consideration of the full range of options for conservation strategies and actions.

Understanding the ecological history of a taxon has potential to play an important role in species conservation programs and should be a priority early in the development of conservation plans.

Keywords: Blandowski Expedition, conservation strategies, ecological history, historical niche, Notomys mitchellii, realised niche, recency bias, relictual distribution, Surveyor-General Thomas Mitchell.

Introduction

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, many species of Australian small- to medium-sized terrestrial mammals suffered rapid and extensive declines in distribution and abundance (McKenzie et al. 2007; Woinarski et al. 2015). As a result, many Australian mammal species currently occupy relictual distributions and habitats; that is, the current realised niche is a subset of the historical niche (Scheele et al. 2017). Often these declines happened quickly, went unnoticed and received little or no documentation. Consequently, knowledge of the historical niche of such species is fragmentary or lost entirely. This poor information base hampers conservation efforts by its potential to restrict consideration of the full range of conservation options for relictual species (Bilney 2014).

Ecological history uses the interpretation of historical records through an ecological lens to infer information about past ecological conditions and environmental processes. The aim is to gain insights that can be applied to current management of land or populations. Ecological history often relies on historical information that was documented for other purposes such as personal reminiscences (Abbott 2008a). Narratives such as these require careful interpretation, and caution is needed to avoid over-interpretation of what may have been incidental comments or unintentional (or deliberate) silences on a particular subject. Investigators also need to be alert for cases of misidentification and imprecise or erroneous locality information. To reduce the likelihood of such errors, historical records from non-scientific sources should be interpreted with reference to scientific sources such as museum specimens and the contemporaneous and recent scientific literature (Abbott 2008a). Even specimen records can mislead due to a past lack of attention to precise locality descriptions, for example, sometimes the place of residence of the collector was recorded rather than the actual collection locality (P. Menkhorst, unpubl. data).

Despite these caveats, information gleaned from diverse historical sources, and interpreted from an ecological perspective, has potential to shed light on the pre-European distribution and habitat of species that have declined, and the drivers of those declines. This is particularly true of Australian mammals but applies equally to any conspicuous plant or animal taxon. In addition to the published natural history and scientific literature, fruitful sources of historical information on Australian mammals include traditional knowledge passed through generations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (e.g. Burbidge et al. 1988), examination of sub-fossil bone accumulations (Bilney 2014; Fusco et al. 2016), published records and specimens collected by European explorers and early settlers (e.g. Denny 1994; Abbott 2008a; Menkhorst 2009, 2011), and published histories of European settler communities and industries (Lunney and Leary 1988; Lunney 2001; Menkhorst 2023), including contemporary newspaper accounts now readily accessible through the Trove database of the National Library of Australia (Abbott 2008a, 2011).

Here, as a case study, information on the activities of two colonial exploration parties that traversed the middle reaches of the Murray River valley, south-eastern Australia, in the mid-19th century (1836, 1856–1857) is used to re-interpret the habitat breadth of Mitchell’s Hopping Mouse (Notomys mitchellii) in south-eastern Australia. This re-interpretation improves our understanding of the species’ ecology and provides new perspectives that have potential to broaden current conservation strategies for the species.

N. mitchellii is an ‘old endemic’, murid rodent that is widely but patchily distributed in semi-arid, southern Australia (Watts and Aslin 1981; Bennett and Lumsden 1995; Woinarski 2017). It is one of 10 species in the genus Notomys, although it is likely that the genus includes further undescribed, cryptic species (e.g. Vakil et al. 2023). Half of these 10 species are extinct, having disappeared within a few decades of European occupation of their habitat (Woinarski et al. 2014, p. 46). Although widespread, N. mitchellii has declined in distribution to the extent that it is considered extinct in the state of New South Wales (Dickman 1993).

In the eastern portion of its distribution, east of the Eyrean Barrier, South Australia (Schodde 1982), N. mitchellii is now confined to dense dune heath mallee vegetation communities growing on deep aeolian, siliceous sands of the Molineaux Formation within the Lowan Mallee biogeographic sub-region (Watts and Aslin 1981; Bennett and Lumsden 1995; Bennett et al. 2007; Woinarski 2017). However, the type specimen, collected in 1836, and numerous specimens collected in 1857, come from different landforms and habitats than those currently occupied.

This paper examines the implications of these early records for our understanding of the ecology of N. mitchellii as an example of how generational memory loss and recency bias can lead to misguided assumptions about the ecology of a species.

The two exploration expeditions that provided the early records of N. mitchellii in south-eastern Australia are:

Surveyor-General Thomas Mitchell’s third expedition through what is now southern New South Wales and western Victoria in 1836 (Mitchell 1839). This was the first incursion by Europeans into the region.

The Blandowski Expedition of 1856–1857 to the mid-Murray and lower Darling rivers (Allen 2009).

The relevance of these two expeditions to N. mitchellii is as follows:

The type specimen of N. mitchellii was collected during Mitchell’s third expedition (Ogilby 1838; Mahoney 1982).

The Blandowski Expedition collected at least 96 specimens of N. mitchellii (Krefft 1866; Wakefield 1966a) and recorded the first observations of its natural history by European scientists (Krefft 1866).

Materials and methods

Recent detailed studies of historical records about the two expeditions have provided new insights and precision to our understanding of their routes, timing and activities (Eccleston 1985, 1992, 2018; Allen 2009). As an experienced land surveyor, Eccleston, for the first time, accurately plotted the locations of the routes followed by Mitchell and the campsites used by the expedition party (Eccleston 1985). Eccleston’s (1985) first interpretation was further refined after Eccleston was able to systematically transcribe and interpret the original field books of Mitchell’s second-in-command, Granville William Chetwynd Stapylton (Eccleston 1992, 2018). Stapylton’s field books are in private hands in England, but Eccleston was able to make a copy which is now lodged in the Australian National Library (Eccleston 2018, pp. xii–xiii).

As part of a celebration of the sesquicentenary of the Blandowski Expedition, a conference examining the history and significance of the expedition was held in September 2007. This conference and its proceedings (Allen 2009) provided new insights into the expedition’s activities and scientific results, for example, the expedition’s highly significant contribution to Australian mammalogy (Menkhorst 2009).

This new and more detailed understanding of the activities of both exploration parties has allowed a re-interpretation of ecological aspects of the natural history observations and specimens collected. Importantly, it has provided increased confidence in pinpointing the collection localities of specimens, thus providing greater powers of inference about the environments inhabited by N. mitchellii at the time. Interpretation of these literature sources was facilitated and enhanced by field inspections of relevant locations opportunistically undertaken by the author over several decades.

Results

The type specimen and the type locality

The type specimen of N. mitchellii was collected on 21 June 1836, during Surveyor-General Thomas Mitchell’s third exploring expedition (Mitchell 1839; Mahoney 1982). A female, it was probably1 collected by two Aboriginal youths who were members of the expedition. Mitchell (1839) presented a ‘Systematical List of Animals’ (page xvii) which includes the following:

6. Dipus Mitchellii. Ogilby. (New Species.) Vol. ii. P. 143. From reedy plains, near the Murray.2

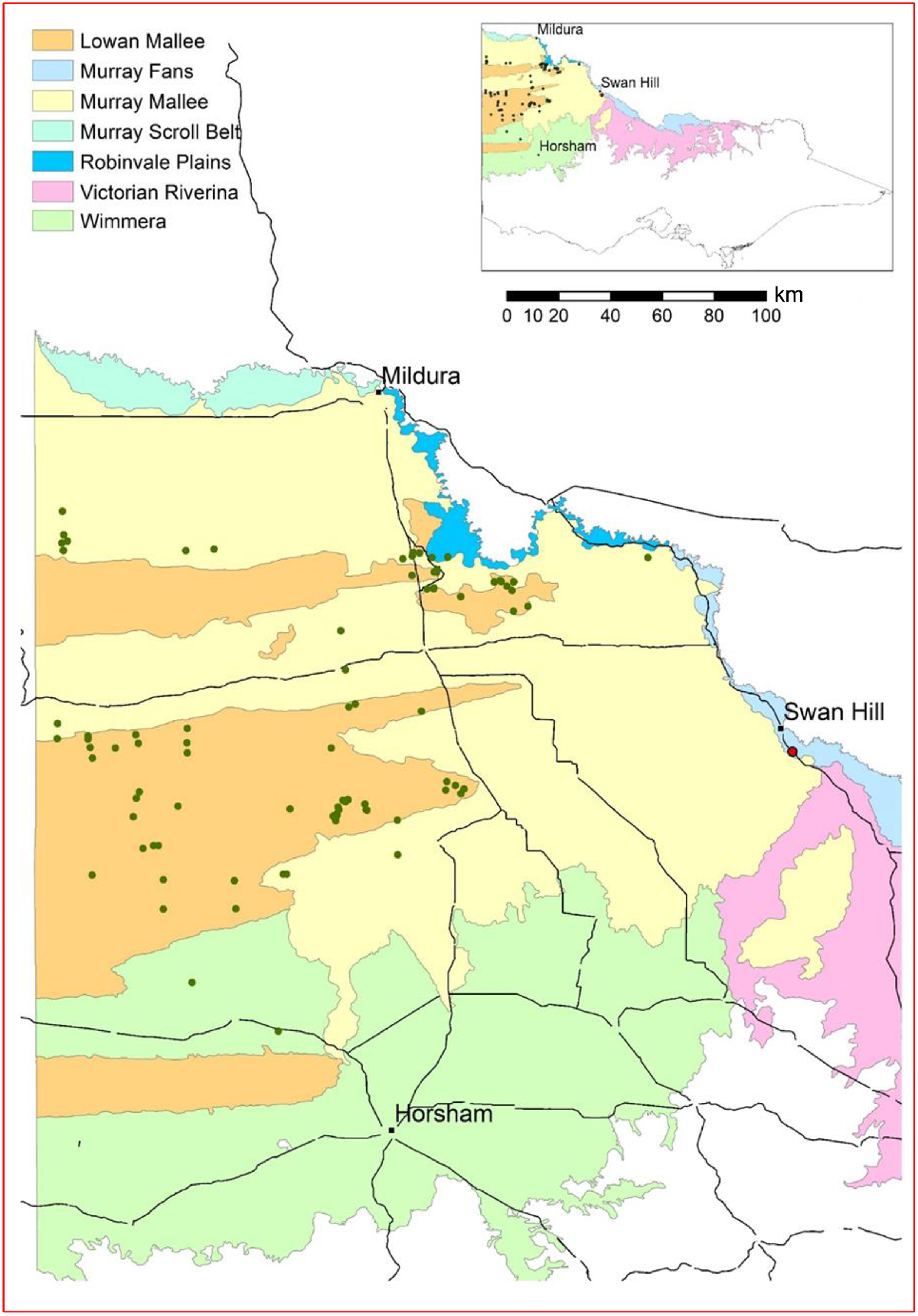

However, on the published route map (Mitchell 1839, first ed. opposite page 348), the label ‘The Jerboa found here 21 June’ indicates a discrete area about 10–12 km south-south-east of Lake Boga township and 12–14 km south of the path followed by the exploration party on 21 June that followed the Little Murray River, an anabranch of the Murray River (Fig. 1). Further, the area indicated on Mitchell’s map is not on the Murray floodplain and therefore unlikely to have been supporting reedy vegetation.

Map of key localities mentioned, and the route followed by Mitchell’s party on 21 June 1836 as determined by Eccleston (1985) (dashed line). The red zone encompasses the probable type locality of Notomys mitchellii. Mitchell’s small-scale map (Mitchell 1839, opposite page 348) indicates that the type locality was roughly between the current day localities of Tresco and Mystic Park, however, there is no indiction that members of the expedition actually visited that area.

When describing the species, Ogilby (1838) approximated the type locality as ‘Reedy Plains, near the junction of the Murray and Murrumbidgee’. Subsequently, two locations (near Lake Boga and near the junction of the Murray and Murrumbidgee rivers), which are about 100 km apart, have been used by different authors to describe the type locality. Wakefield (1966b) took Mitchell’s map at face value and described the type locality as south-east of Lake Boga, and this interpretation was supported by Mahoney (1982, p. 18).

More recently, the detailed mapping of the expedition’s route undertaken by Eccleston (1985) has suggested that the placement of the words ‘The Jerboa found on 21 June’ on Mitchell’s small-scale map is, at best, an approximation of the actual type locality. We now know that Mitchell’s party crossed to the south bank of the Murray River on 13 June 1836, some 4 km (straight line distance) downstream of its confluence with the Murrumbidgee River (at the site now known as Passage Camp Nature Conservation Reserve) and camped nearby for two nights to allow the livestock to recover (Eccleston 1985). The party left Passage Camp on 15 June 1836 and had travelled roughly 100 km south-south-east by 20 June when they made camp close to the confluence of the Murray River and its anabranch the Little Murray River (i.e. at present-day Swan Hill) (Eccleston 1985, 2018, p. 16). Further, it is clear that on 21 June, the party travelled south, passing to the west of Lake Baker and then turning east and passing between the Little Murray River and Lake Boga (Eccleston 1985) (Fig. 1). As they negotiated a dense reedbed around the inlet creek at the north end of Lake Boga, the party unexpectedly entered an established village of the local Indigenous people who fled by canoe to an island in Lake Boga. Mitchell’s party continued eastwards following the course of the Little Murray River before spending a cold and uncomfortable night (without wood for a warming fire) on a treeless plain on the south bank of the Little Murray River close to the present-day location of Fish Point (Eccleston 1985, map 5; Eccleston 2018, p. 49). Critically, after disturbing the Indigenous people, Mitchell asked the Aboriginal men in the party (John Piper and the two Aboriginal youths) to remain behind at the Lake Boga inlet to seek information from the local people about their indigenous names for local topographic features (Mitchell 1839; Eccleston 1985). Later that day, an altercation between the two groups resulted in tragedy when a local man was killed, allegedly by John Piper (Mitchell 1839; Eccleston 1985).

If Mitchell’s map showing the area in which the hopping mouse was collected is to be taken at face value, then the party must have split at some time on 21 June, with the two Aboriginal youths and/or Roach taking a route well to the south of Lake Boga. There is no mention of such a diversion in either Mitchell’s or Stapylton’s records, and the two Aboriginal youths were present at the north side of Lake Boga when the tragic interaction with the local Indigenous people occurred. Therefore, it seems more likely that the specimen was captured as the expedition travelled south-south-east from the confluence of the Murray and Little Murray Rivers before encountering the local Indigenous people on the northern edge of Lake Boga. This hypothesis places the type locality south or west of the Little Murray River between its confluence with the Murray River and the north-western edge of Lake Boga, a distance of some 12 km (Fig. 1).

An alternative possibility is that the specimen had been captured by the local Indigenous people and was removed from their village by expedition members after the local people fled.

The holotype was lodged by Mitchell in the Australian Museum and is catalogued as AM 22 (Bennett 1837), but it cannot now be found (Mahoney 1982; Parnaby et al. 2017, p. 407).

The type location is the most easterly record of the species. As proposed here, its location lies along the edge of two bioregions: (1) the Riverina (Murray Fans sub-region); and (2) the Murray–Darling Depression (Murray Mallee sub-region) (Fig. 2). Based on the ecology of N. mitchellii, especially its construction of extensive and deep burrow systems (Watts and Aslin 1981), it is unlikely that N. mitchellii occurred in areas subject to regular flooding,3 such as the extensive reedbeds intimated by Mitchell as the habitat at the type locality. Rather, it is more likely that the specimen was captured in the sandhills adjacent to the floodplain somewhere north-north-west of Lake Boga and before the altercation with the local Indigenous people. Therefore, it is suggested that the type locality was most likely within the Murray Mallee sub-region, on red sand dunes of the Woorinen Formation (Costermans and VandenBerg 2022) (or ‘bergs’; see Mitchell (1839)) that interdigitate with the heavier soils of the Murray Fans sub-region along Mitchell’s route (the boundary between these bioregions closely approximates the route of the Murray Valley Highway between Lake Boga and Swan Hill, itself closely approximating Mitchell’s probable route). In particular, dunes formed on the downwind sides of deflation lake basins (often called lunettes) provide deep sand that would seem to provide ideal habitat for N. mitchellii. As an example of this geomorphological feature, remnants of the Lake Baker lunette, which was likely to have been crossed by Mitchell’s party, are shown in Fig. 3. It is also notable that a specimen of the semi-arid shrub Senna artemisioides was also collected on this day, indicating that members of the party at some point travelled off the floodplain and across the adjacent red sand dunes, potential habitat of N. mitchellii.

Mitchell described the country traversed on 21 June 1836 as ‘… reedy plains near the Murray’. Stapylton’s description of the country traversed that day4 differs in that it makes no mention of reed beds, rather it seems to describe the upper levels of the floodplain: ‘Country not so good, large forests of low box trees (Gobbra) [likely Black Box Eucalyptus largiflorens] and occasionally flats covered with fine grass, but on a white tenacious clay’ (Eccleston 2018, pp. 48–49).

The area traversed by Mitchell’s party on 21 June 1836 was extensively cleared of natural vegetation in the early 20th century and is now intensively farmed with irrigated pasture and horticultural crops, often on laser-levelled paddocks. Fig. 2 illustrates the remnants of the Lake Baker lunette and lake bed, which is now improved pasture grazed by cattle. Apart from narrow bands of River Red Gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) forest bordering the major streams and wetlands, the region is almost entirely devoid of locally indigenous vegetation (and native terrestrial mammals). Remnant native vegetation in the Mystic Park Bushland Reserve, between Mystic Park and Tresco, provides an indication of the habitat in that area; that is, Black Box woodland with a low shrub understorey dominated by Chenopodaceae growing on a fine, pale clay soil, thus according with Stapylton’s description of the country traversed on 21 June. It is probable that much of the area around Lake Boga carried similar vegetation at the time of the expedition.

Almost exactly 20 years after Mitchell’s traverse (1856–1857), the Blandowski Expedition travelled a similar route although in the opposite direction (Allen 2009; Menkhorst 2009). Referring to N. mitchellii, expedition zoologist Gerhard Krefft (1866) stated that he was ‘unable to procure specimens at Gunbower Creek (35.86°S, 143.96°E) or at the Junction of the Loddon’ (approximately 21 km east-south-east of the type locality postulated here). ‘The first pair obtained were brought to me by natives in the neighbourhood of the Murrumbidgee’ (the confluence of the Murrumbidgee and Murray Rivers is 102 km north-north-west of the type locality as postulated here and about 50 km west-south-west of the most easterly modern records from the Molineaux Sands of the Annuello Flora and Fauna Reserve) (Fig. 2).

From April to November 1857, the Blandowski Expedition was based on the south bank of the Murray River at Mondellimin (now known as Chaffey Landing, Merbein) (Menkhorst 2009). Blandowski paid local Indigenous people to collect fauna specimens. With the aid of local women of the Yerri-Yerri (Mildura area) and Yako-Yako (lower Darling River) language groups (Hercus 2010), numerous N. mitchellii specimens were preserved and recorded in the catalogue of specimens collected during the expedition (Wakefield 1966a). Krefft (1866) described the species as being ‘very plentiful on the Darling: and as many as 50 specimens were often procured by the native women in an afternoon. It burrows into the ground and is dug out by them.’ Use of the term ‘on the Darling’ is here taken to mean the area north of the Murray River between the Darling River and the expedition camp at Mondellimin, approximately 16 km upstream along the Murray from the confluence of those two rivers. It is possible that the local people travelled further afield to collect or trade specimens, encouraged by payments offered by Blandowski (e.g. flour, sugar, tea, blankets and clothing) (Blandowski 1857); and according to Krefft (n.d.), also in cash at the ‘exorbitant rate’ of one shilling per specimen. This expanded collecting area likely included travelling northwards along the Darling River (Menkhorst 2009).

N. mitchellii is now presumed to be extinct in New South Wales (https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/threatenedspeciesapp/), there having been no records since the Blandowski Expedition (Dickman 1993).

Of the suite of small mammal species that presently occupy the Molineaux Sands of the Lowan Mallee sub-region, only N. mitchellii was collected during the Blandowski Expedition. The lack of specimens of the Lowan Mallee specialists Southern Ningaui (Ningaui yvonnae), Western Pygmy Possum (Cercartetus concinnus), Little Pygmy Possum (Cercartetus lepidus) and Silky Mouse (Pseudomys apodemoides) (Bennett et al. 2007) indicates that little or no collecting was undertaken in the Lowan Mallee sub-region (i.e. on Molineaux Sands) during the Blandowski Expedition (Menkhorst 2009), yet some 96 specimens of N. mitchellii were registered by Krefft. This indicates that N. mitchellii was widespread in other environments, notably Krefft’s ‘on the Darling’, likely including areas of the Darling Riverine Plains, Murray–Darling Depression and Riverina bioregions (Table 1). This interpretation concurs with the evidence from the type locality in broadening current understandings of the habitat of N. mitchellii to include taller, more open mallee eucalypt woodland and Allocasuarina/Callitris woodlands with grasses or chenopods dominating the understoreys.

| Bioregion | Bioregional sub-regions | Main stratigraphic units | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Darling Riverine Plains | DRP08 Great Darling Anabranch | Woorinen Formation | |

| DRP09 Pooncarie–Darling | Woorinen Formation, Molineaux Sand | ||

| DRP07 Menindee | As above, Shepparton Formation | ||

| Murray–Darling Depression | MDD01 South Olary Plain | Woorinen Formation, Pooraka Formation | |

| MDD02 Murray Mallee | Woorinen Formation, Loxton Sand | ||

| MDD04 Lowan Mallee | Molineaux Sand | ||

| Riverina | RIV03 Murray Fans | Quarternary alluvium | |

| RIV04 Victorian Riverina | Shepparton Formation | ||

| RIV05 Robinvale Plains | Woorinen Formation | ||

| RIV06 Murray Scroll Belt | Quarternary alluvium |

Note: there is no compelling evidence that the distribution of N. mitchellii extended south to the Wimmera Sub-region of the Murray-Darling Depression Bioregion despite the record of Brazenor (1958) who likely mistook burrows of the Silky Mouse Pseudomys apodemoides in the Little Desert for those of N. mitchellii (Wakefield 1966b; Menkhorst and Beardsell 1982).

Discussion

The distribution and habitat of N. mitchellii east of the Eyrean Barrier

Increasing the precision of our understanding of the type locality of N. mitchellii and further consideration of the findings of the Blandowski Expedition has provided new insights into the former ecological breadth of N. mitchellii in south-eastern Australia. Modern records of N. mitchellii from the Murray–Darling Depression bioregion are entirely from the deep Molineaux Sands of the Lowan Mallee sub-region (Big Desert, Sunset Country and Annuello Flora and Fauna Reserve and nearby uncleared areas in South Australia) (Bennett and Lumsden 1995; Foulkes and Gillen 2000). However, the type locality is in a different biogeographic sub-region (Murray Mallee sub-region), stratiographic unit (Woorinen Formation) and has different vegetation characteristics to the species’ currently accepted distribution and habitat (Lowan Mallee sub-region, Molineaux Sands, dune heath mallee communities). The type locality and the notes of Krefft (1866) indicate a wider distribution that likely included two other bioregions and perhaps six other biogeographic sub-regions (Table 1).

The type locality postulated here is some 105–110 km south-east of the nearest modern (i.e. post 1960) records of N. mitchellii that are from the Annuello Flora and Fauna Reserve (Victorian Biodiversity Atlas, Bennett and Lumsden 1995) (Fig. 2), part of the Lowan Mallee sub-region. Further, the habitats so prolifically sampled during the Blandowski Expedition apparently did not include those currently occupied by the species, confirming that the current realised niche (contemporary niche) is a subset of the historical niche.

Implications for conservation of N. mitchellii

This investigation of the recent ecological history of N. mitchellii in south-eastern Australia indicates that the species occupied a much wider range of environments than modern (post 1960) records indicate, bringing into consideration a far greater breadth of habitat and a huge increase in the area included in its former distribution.

Presumably N. mitchellii was unable to persist in these grassy woodland habitats because they were more intensively affected by environmental changes resulting from European occupation than were the dune heath mallee vegetation communities growing on the Molineaux Sands. Critical environmental changes in the Murray Mallee sub-region and surrounding areas in the decades following European occupation of the region likely included:

Loss of long-standing (many 1000s of years) burning regimes applied by Indigenous peoples that maintained productivity in grassy ecosystems (Mansergh et al. 2022).

Loss of vegetation cover and topsoil resulting from unsustainable grazing of livestock, mostly sheep, but also cattle, goats and horses, from the 1840s (particularly severe during periods of low rainfall).

Further grazing pressure from introduced wild herbivores (European Rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus and, to a lesser extent, European Hare, Lepus europaeus) from the late 1860s. The combined impacts of sheep, rabbits and low rainfall was catastrophic (Morton 1990; Lunney 2001).

Predation by introduced carnivores – feral populations of Domestic Cat (Felis catus) from about 1860 (Abbott 2008b) and Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) from about 1894 (Abbott 2011).

Clearing of indigenous vegetation for cropping and horticulture (late 1800s and very extensively after World War 1) (White et al. 2003; Broome et al. 2020).

The new understanding of a broader distribution and habitat for N. mitchellii opens new possibilities for conservation action. Extinct in NSW (Dickman 1993; Lunney 2001), and now restricted to dune heath mallee communities growing on the Molineaux Sands of north-western Victoria and eastern South Australia, the species could certainly be considered a candidate for re-introduction to other landscapes in inland south-eastern Australia. These include grassy tall mallee eucalypt and Allocasuarina/Callitris woodlands growing on the sandy loams of the Woorinen Formation in the Murray Mallee sub-region and in the Pooncarie–Darling and Menindee sub-regions north of the Murray River. The current proposal by the New South Wales Government and Australian Wildlife Conservancy to include the species in a group of 10 mammal species being released into a feral predator exclosure at Mallee Cliffs National Park (https://www.australianwildlife.org/where-we-work/mallee-cliffs-national-park/) (accessed 30 September 2021) is one such example. Preferably, releases could take place in an area with high habitat heterogeneity so that the animals can exhibit choices in habitat selection, which would further inform our understanding of the species’ habitat breadth.

The role of ecological history in conservation planning more generally

Mitchell’s Hopping Mouse provides a salutary lesson of the importance of understanding the full breadth of a species’ habitat and distribution (the historical niche) before developing detailed conservation plans, and not assuming that the present-day distribution and habitat (the contemporary realised niche) represent the full story. This is particularly so for Australian small- to medium-sized terrestrial mammals, many of which survive only as relictual populations. One important caveat to this strategy is that conservation managers need to be alert to the potential for the relictual population to have lost genetic and phenotypic diversity. Animals translocated from a narrow range of habitats to which they are locally-adapted may not have the necessary genetic or phenotypic capacity to survive in a new environment. Thus, an experimental approach is recommended (Seddon et al. 2007).

Examples of other Australian mammal species that occupy a contemporary realised niche that is a small fraction of the historical niche, and may therefore benefit from detailed investigation of their ecological history, include: Red-tailed Phascogale (Phascogale calura), Numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus), Golden Bandicoot (Isoodon auratus), Greater Bilby (Macrotis lagotis), Eastern Bettong (Bettongia gaimardi), Bridled Nail-tailed Wallaby (Onychogalea frenata), Northern Hopping Mouse (Notomys aquilo) and Golden-backed Tree-rat (Mesembriomys macrurus).

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were generated or analysed during this study.

Acknowledgements

I thank Ian Sluiter for sharing knowledge of the soils and landforms of the Murray Mallee region. I also thank Lindy Lumsden and two anonymous referees provided very helpful comments on drafts. Tess McLaren and Khorloo Batpurev kindly produced the maps.

References

Abbott I (2008a) Historical perspectives of the ecology of some conspicuous vertebrate species in south-west western Australia. Conservation Science Western Australia 6(3), 1-214.

| Google Scholar |

Abbott I (2008b) The spread of the cat, Felis catus, in Australia: re-examination of the current conceptual model with additional information. Conservation Science Western Australia 7(1), 1-17.

| Google Scholar |

Abbott I (2011) The importation, release, establishment, spread, and early impact on prey animals of the red fox Vulpes vulpes in Victoria and adjoining parts of south-eastern Australia. Australian Zoologist 35, 463-533.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Allen H (2009) Introduction: Looking again at William Blandowski. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 121, 1-10.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bennett AF, Lumsden LF, Menkhorst PW (2007) Mammals of the mallee region, Victoria: past, present and future. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 118, 259-280.

| Google Scholar |

Bilney RJ (2014) Poor historical data drive conservation complacency: the case of mammal decline in south-eastern Australian forests. Austral Ecology 39, 875-886.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Blandowski W (1857) Recent discoveries in natural history on the Lower Murray. Transactions of the Philosophical Society of Victoria 2, 124-137.

| Google Scholar |

Brazenor CW (1958) Mitchell’s hopping mouse. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of New South Wales 1956-57, 19-22.

| Google Scholar |

Burbidge AA, Johnson KA, Fuller PJ, Southgate RI (1988) Aboriginal knowledge of the mammals of the central deserts of Australia. Wildlife Research 15, 9-39.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Denny M (1994) Investigating the past: an approach to determining the changes in the fauna of the Western Division of New South Wales since the first explorers. In ‘Future of the fauna of Western New South Wales’. (Eds D Lunney, S Hand, P Reed, D Butcher) pp. 53–63. (Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales: Sydney)

Fusco DA, McDowell MC, Prideaux GJ (2016) Late-Holocene mammal fauna from southern Australia reveals rapid species declines post-European settlement: implications for conservation biology. The Holocene 26, 699-708.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Krefft JLG (1866) On the vertebrated animals of the lower Murray and Darling, their habits, economy, and geographical distribution. Transactions of the Philosophical Society of New South Wales 1862–1865, 1-33.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lunney D (2001) Causes of the extinction of native mammals of the western division of New South Wales: an ecological interpretation of the nineteenth century historical record. The Rangeland Journal 23, 44-70.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lunney D, Leary T (1988) The impact on native mammals of land-use changes and exotic species in the Bega district, New South Wales, since settlement. Australian Journal of Ecology 13, 67-92.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mahoney JA (1982) Identities of the rodents (Muridae) listed in T. L. Mitchell’s “Three Expeditions into the Interior of Eastern Australia, with descriptions of the recently explored region of Australia Felix, and of the present colony of New South Wales” (1st ed., 1838; 2nd ed., 1839). Australian Mammalogy 5, 15-36.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mansergh IM, Cheal DC, Burch JW, Allen HR (2022) Something went missing: cessation of traditional owner land management and rapid mammalian population collapses in the semi-arid region of the Murray–Darling Basin, southeastern Australia. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 134, 45-84.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McKenzie NL, Burbidge AA, Baynes A, Brereton RN, Dickman CR, Gordon G, Gibson LA, Menkhorst PW, Robinson AC, Williams MR, Woinarski JCZ (2007) Analysis of factors implicated in the recent decline of Australia’s mammal fauna. Journal of Biogeography 34, 597-611.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Menkhorst PW (2009) Blandowski’s mammals: clues to a lost world. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 121, 61-89.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Menkhorst P (2023) ‘Three sorts of kangaroo’: which species did James Hamilton recognise in south-western Victoria in the mid-19th century? The Victorian Naturalist 140, 161-165.

| Google Scholar |

Menkhorst PW, Beardsell CM (1982) Mammals of southwestern Victoria from the Little Desert to the coast. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 94, 221-247.

| Google Scholar |

Morton SR (1990) The impact of European settlement on the vertebrate animals of arid Australia: a conceptual model. Proceedings of the Ecological Society of Australia 16, 201-213.

| Google Scholar |

Ogilby W (1838) V. Notice of certain Australian Quadrupeds, belonging to the Order Rodentia. Transactions of the Linnean Society of London os–18(1), 121-132.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Parnaby HE, Ingleby S, Divljan A (2017) Type specimens of non-fossil mammals in the Australian Museum, Sydney. Records of the Australian Museum 69, 277-420.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Scheele BC, Foster CN, Banks SC, Lindenmayer DB (2017) Niche contractions in declining species: mechanisms and consequences. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 32, 346-355.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Seddon PJ, Armstrong DP, Maloney RF (2007) Developing the science of reintroduction biology. Conservation Biology 21, 303-312.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Vakil V, Cramb J, Price GJ, Webb GE, Louys J (2023) Conservation implications of a new fossil species of hopping-mouse, Notomys magnus sp. nov. (Rodentia: Muridae), from the Broken River Region, northeastern Queensland. Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology 47, 590-601.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wakefield NA (1966a) Mammals of the Blandowski Expedition to north-western Victoria, 1856-57. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 79, 371-391.

| Google Scholar |

Wakefield NA (1966b) Mammals recorded for the Mallee, Victoria. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 79, 627-636.

| Google Scholar |

White M, Oates A, Barlow T, Pelikan M, Brown J, Rosengren N, Cheal D, Sinclair S, Sutter G (2003) The vegetation of North-west Victoria: a report to the Mallee, Wimmera and North Central Catchment Management Authorities. Arthur Rylah Institute for Environmental Research and Ecology Australia, Melbourne.

Woinarski JCZ, Burbidge AA, Harrison PL (2015) Ongoing unraveling of a continental fauna: decline and extinction of Australian mammals since European settlement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 4531-4540.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Footnotes

1 Mitchell credits the discovery of the specimen to two different sources (see Mahoney 1982, page 18). In the field notes for 21 June 1836, Mitchell states that it ‘was found by Roach’ (John Roach, the expedition’s collector of birds), then in this published account of the expedition (Mitchell 1839), it states that it was captured by the ‘two Tommies’, i.e. two aboriginal youths who joined the expedition near Booligal, NSW in early May 1836 and were referred to by European members of the expedition as Tommy Came-first and Tommy Came-last.

2 Mitchell provisionally identified the specimen as a species of Jerboa (Dipodoidea) and British Museum zoologist W. Ogilby, who described the species based solely on Mitchell’s drawing, followed suit and placed it in the genus Dipus (Ogilby 1838). Seven years later, John Gould (Gould 1845) correctly judged that it is a murid rodent and placed it in the genus Hapalotis.

3 In its natural state the floodplain of the Murray River was at least partially inundated in spring of most years (VEAC 2008).

4 Stapylton appears to have been confused about the dates and his diary records the date of collection of the hopping mouse specimen as 26 June. Note that the quote above regarding the country traversed is taken from Stapylton’s 26 June diary entry. Stapylton’s description of the campsite in his 26 June diary entry indicates that it was near the point where the Little Murray River anabranch leaves the Murray River, and this accords with his dates being advanced by about 5 days compared to those of Major Mitchell.