Hiding in plain sight: highlighting the research gap on access to HIV and other sexual health services for underrepresented gay men in developed Western countries – insights from a scoping review with a focus on Arab men

Bernard Saliba A B * , Melissa Kang

A B * , Melissa Kang  C , Nathanael Wells

C , Nathanael Wells  A , Limin Mao

A , Limin Mao  D , Garrett Prestage

D , Garrett Prestage  A and Mohamed A. Hammoud

A and Mohamed A. Hammoud  A

A

A

B

C

D

Abstract

Strategies pertaining to HIV and sexual health for gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) have shifted focus towards underrepresented subgroups within some developed Western countries. Although emerging research exists on some subgroups, limited attention has been given to the needs of Arab GBMSM in these contexts. Considering they are part of a large diaspora, understanding their access to services is crucial. This paper focuses on Arab GBMSM as a case study within a scoping review, highlighting their hidden status within the broader landscape of HIV and sexual health research for GBMSM in the West.

A multi-method search strategy was employed, including searching four electronic databases using several terms within each of the following search topics: Arab, GBMSM, HIV and other sexual health services, and developed Western countries.

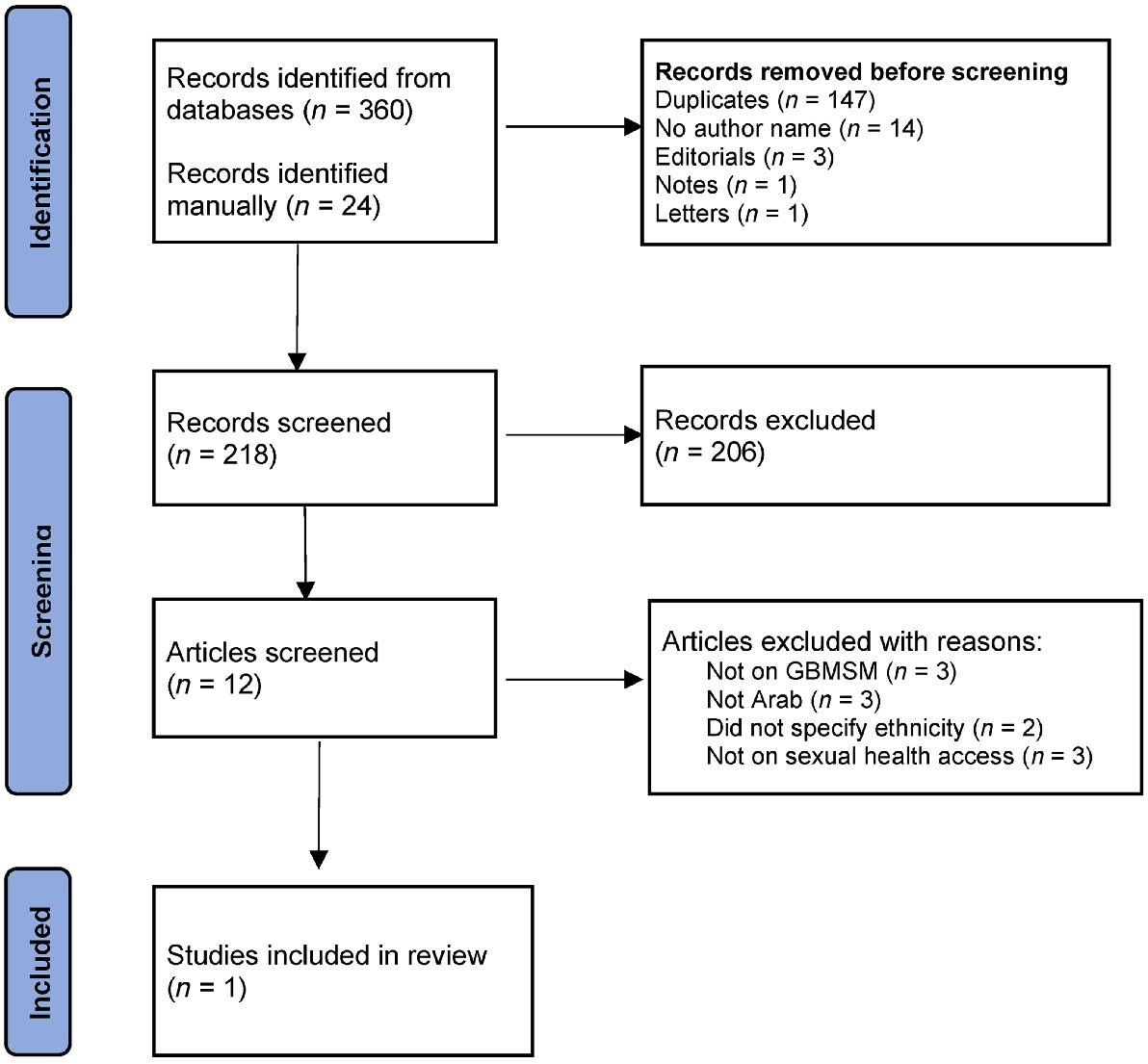

Of the 384 articles found, only one addressed the research question and met the inclusion criteria, revealing a stark scarcity of research on access to HIV and sexual health services for this population.

This review highlights a paucity of research on access to HIV and sexual health services for underrepresented GBMSM populations in developed Western countries. The literature indicates that, for Arab men, this may be due to a difficulty in participant recruitment and poor data collection efforts. By focusing on one hidden population, we aim to advocate for inclusive policies and interventions that promote equitable sexual health access for all. Addressing this research gap aligns with broader local and global HIV strategies to reduce disparities among underrepresented GBMSM populations.

Keywords: Arab, Australia, gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM), health access, HIV research, sexual health, sexual minority men, Western countries.

Introduction

The landscape of HIV research has witnessed a notable decline in infection rates among Western-born gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM), a positive outcome attributed to targeted interventions and comprehensive health strategies.1 In parallel, the attention of state and national HIV strategies, particularly in Australia, has expanded to target culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) and non-gay-identifying GBMSM in areas with lower concentrations of gay-identified men,2,3 acknowledging their heightened vulnerability and prioritising their healthcare needs. In line with this shift, a growing body of research has recently emerged with a focus on overseas-born as well as local-born CALD GBMSM.4–7 Although some groups have been targeted, the experiences of other underrepresented subgroups of GBMSM in developed Western countries may have been inadvertently overlooked, including in Australia, specifically within the context of research and data pertaining to access to HIV and sexual health services.

Underrepresented populations of GBMSM men living in developed Western countries, including those born locally into migrant and ethnic minority communities, face unique challenges related to racism and economic deprivation.8–10 These experiences, which are often influenced by complex intersections of culture, religion, sexuality, socio-economic status, language barriers, and/or migration status, can make it difficult to access appropriate health services, negatively impacting their overall health, such as sexual health outcomes, including increased risk of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).9,11,12 Despite advancements in public health research for mainstream and newly arrived GBMSM populations, some groups of gay men in developed Western countries remain hidden and excluded from data collection, policy formulation, and health promotion efforts. To highlight the hidden status and exclusion of underrepresented gay men within the context of available data on their access to HIV and sexual health services in developed Western countries, we used Arab GBMSM as a case study for our literature review.

The Arab case study

In the broader landscape of hidden GBMSM populations in the developed Western world, Arab men present a compelling case study, offering insights into the unique experiences of individuals who descend from 22 countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region with a range of ethnicities, cultures, and religions.13

It is likely that men from Arab backgrounds make up a meaningful part of the wider GBMSM population in developed Western countries. In countries such as Canada, the US, New Zealand, France, Germany, Italy, and Australia, Arab individuals make up significant portions (ranging from 1 to 10%)14–19 of their total populations. In Australia, Arabic remains the third most spoken language in the country after English and Mandarin.16 Additionally, GBMSM residing within the Arab world are often motivated to migrate to the West in search of sexual freedom.20,21 This motivation can be driven by the fact that, within the Arab world, GBMSM remain a heavily stigmatised group22–26 and often have poor sexual health outcomes, including an increased risk of HIV and STIs.27 Further, a combined fear of legal ramifications due to the illegality of homosexuality, a delay in the acknowledgement of the existence of HIV, as well as HIV and other sexual health-related stigmas, particularly from within healthcare settings,28–30 have led to significant knowledge gaps31 as well as hindered testing, prevention and treatment efforts in large parts of the region.32,33

Within the diaspora, access to HIV and other sexual health services may be more difficult for Arab GBMSM as has been reported for other ethnic minority individuals, such as Asian, Black, Native American, Pacific Islander, and Hispanic men in developed Western contexts.4–7 These groups have reported experiencing multiple forms of discrimination due to their intersecting sexual, religious, and ethnic/cultural identities.8–10 These experiences, which are often influenced by a complexity of other intersections such as culture, religion, sexuality, socio-economic status, language barriers, and/or migration status, can make it difficult to access appropriate health services, negatively impacting their overall health, such as sexual health outcomes, including increased risk of HIV and other STIs.9,11,12 Similarly, heterosexist narratives prevalent in the Arab world transcend geographical borders and present themselves within diasporic Arab communities in the developed Western world.34–39 Although there is some evidence to suggest that younger generations of Arabs are more tolerant than those who came before them,40 homosexuality is generally still not accepted within Arab cultures. In addition to experiences of racism and exoticisation within gay communities,41 some research on migrant and refugee men, including those from Arab backgrounds, indicates that they also experience violence and abuse due to their sexual orientation from within their ethnic communities, at times creating barriers to accessing support services.20,21 Further, very limited data suggest that these men are less likely than their non-Arab counterparts to test for HIV42 and have higher HIV incidence compared to other groups.43

Although there is some research pertaining to access to mental health services for Arab GBMSM,44 the bulk of Arab community-related HIV and other sexual health-related research in developed Western countries has focused only on heterosexual populations.27 Although this is important, it does not reflect the epidemiology of HIV and other sexual health concerns within the context of the developed West, where rates of HIV remain highest among the GBMSM population. Thus, the aim of this paper was to identify, document, and assess the current literature pertaining to the availability and utilisation of HIV and other sexual health services among Arab GBMSM in developed Western countries.

Methods

The research team conducted a rigorous preliminary search of the available literature to inform the scoping review process. Based on this preliminary search, we conducted a scoping review of the literature. Scoping reviews seek to identify knowledge gaps and characterise the breadth of the existing literature on a given topic, lending themselves to broad research questions and, thereby, informing decisions around priorities for future research.45,46 This method is appropriate given the focus and aim of this research, which is to build a comprehensive account of the current literature on Arab GBMSM’s access to HIV and other sexual health services in developed Western countries, rather than to weigh up the levels of evidence in relation to a specific question.45

To map out and identify the extent, range, and nature of research activity, including identifying gaps in the existing literature, we adopted Arksey and O’Malley’s47 systematic methodology for scoping reviews. In accordance with the process, which involves a staged approach, we followed the following five steps to conduct this review: (1) identify the search question; (2) identify relevant studies; (3) finalise study selection; (4) chart the data; and (5) collate, summarise, and report the results. We also adopted the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews: checklist and explanation.46

Identifying the research question

Based on the focus of this paper, the research questions were broadly identified as:

Identifying relevant studies

A multi-method search strategy was employed to identify relevant literature. Several systematic searches were conducted on OVID EMBASE, ProQuest (Medline), PsychInfo and Scopus and were filtered in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. No start date was set for study inclusion, and the search was conducted until October 2022.

The search strategy was drafted by the first author (BS) and further refined through team discussions with the other investigators (MK, MH and GP). In each database, the search was conducted in accordance with the corresponding guidelines for literature searches. The search strategy included variations of controlled and uncontrolled index terms of the following concepts: (1) Arab, (2) GBMSM, (3) HIV and other sexual health services, and (4) developed countries. To capture the Arab identity (1), the Boolean operator ‘OR’ was used to connecte all the Arab nationalities, as well as variations of ‘Islam/Muslim’, in order to capture Muslim-specific publications that may include Arab men. To capture the GBMSM identity (2), umbrella terms such as ‘queer’, ‘LGBT’, ‘gay’, ‘bisexual’, ‘sexual minorities’, and ‘sexuality diverse’ were used. To capture access to HIV and other sexual health services (3), umbrella terms such as ’HIV’, ‘sexual health’, ‘chlamydia’, ‘syphilis’, and ‘gonorrhea’ were used. To capture developed Western countries (4), a list of countries, including the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and large parts of Europe – in accordance with the 2019 United Nations’ Country Classification report –48 was used. The Boolean operator ‘AND’ was used to connect the four concepts. The search strategy, including all relevant search terms, is outlined in the Supplementary material. No filter searches or language restrictions were applied to capture all available research on this topic. Additionally, the snowball method and manual reference tracking of recent literature reviews on similar topics27,49 were conducted to ensure that all potentially relevant studies were included.

Study selection

We developed selection criteria through an iterative process that involved the examination of the references and discussions between two authors (BS and MH). The authors aimed to include peer-reviewed published papers that reported on primary data outlining the experiences of Arab GBMSM in developed countries; focused on access to HIV and other sexual health services, including testing and prevention; and presented interventions aimed at addressing stigma around sexuality and sexual health. Our aim was to examine outcome measures that included sexual health perceptions and knowledge, skill development, increased testing and/or preventative uptake, and general health-seeking behaviours. Prevalence-only papers, mortality reports, studies on healthcare workers’ perspectives, and studies on sexual/erectile dysfunction were excluded.

Charting the data

A summary table was drafted by the first author (BS) with the following headings: study location, year conducted, study purpose, study focus/measures, study design, participants (including sample size, ethnicity, country of birth, gender identity, age, sexual orientation, and religion), and main sexual health findings (including definitions of access, sexual practices, sexual knowledge, access to testing, reason for testing, access to HIV preventatives [such as PrEP], regularity of engagement, and barriers and/or facilitators). Two other authors (MK and MH) aimed to independently extract and compare the relevant data from the full text of eligible studies. Due to the scarcity of literature that met the inclusion criteria, however, the summary table was not used.

Results

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the final search results (n = 384) were exported to EndNote. After duplicates (n = 147), titles without author name (n = 14), editorials (n = 3), notes (n = 1), and letters (n = 1) were removed, of the remaining 194 records, 182 were excluded for not meeting our study aim. Two authors (BS and MH) independently examined the remaining 12 papers against the selection criteria and agreed on the exclusion of 11 that did not meet the inclusion criteria; three studies did not discuss GBMSM in their findings, three studies did not separate findings for ethnic groups, two did not report the ethnicity of the sample, and three did not focus on access to HIV and/or other sexual health services.

Fig. 1 below provides an overview of the extraction process used to identify the relevant articles for the search.

Characteristics of included study

In our extensive literature review, only one article, authored by Lessard et al.,50 met the inclusion criteria of our study. The study analysed the experiences of migrant GBMSM in Canada, specifically their use of Actuel sur Rue (AsR), a rapid HIV testing and linkage point to a local clinic – Clinique médicale l’Actuel – that specialises in the testing and treatment of HIV and sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBIs) in Montreal. From the sample of 40 GBMSM who took part in the study, only 15% of the participants (n = 6) identified themselves as migrants originating from the MENA region.

Our initial analysis revealed that the available data from this subgroup, although limited in size, offered valuable insights into the facilitators for accessing HIV testing and treatment services among Arab GBMSM in a Western context. Notably, these facilitators encompassed factors that are commonly associated with HIV risk, such as recent risk-taking behaviours, experiencing symptoms of STBBIs, and a prior lack of HIV testing. However, it is essential to clarify that the study did not directly compare the knowledge or behaviours of these men with a broader population of Arab GBMSM in Canada. Instead, it sought to understand the specific context in which these men sought HIV testing and treatment services at AsR. The study’s general findings provide valuable insights into the factors influencing HIV testing and treatment among a subgroup of migrant GBMSM. Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge the limitations associated with the small sample size (n = 6) of men from the MENA region and the potential for recall bias due to the 2-month gap between the clinic visit and survey completion.

Discussion

The scoping review focused on literature that examined the availability and utilisation of HIV and other sexual health services among Arab GBMSM in developed Western countries. The findings revealed a paucity of research in this area, highlighting the lack of available information regarding the access and utilisation of these services among this population. This finding highlights several important knowledge gaps to guide future research directions on Arab GBMSM populations residing in Western countries, including Australia.

Despite being part of both the GBMSM population and a large diaspora, Arab GBMSM in developed countries remain an underrepresented population from both mainstream GBMSM and diasporic Arab research, meaning their needs remain largely unknown. Although there is literature on Muslim GBMSM populations,49 the focus is often on groups from South-Asian descent. Further, a significant proportion of the developed world’s Arabic communities are non-Muslim. For example, the majority of Lebanese- and Egyptian-born Australians (55% and 84% respectively) are Christian,51 and large European communities of Arabs trace their migration roots back to the 1800s when many Christians left the Arab world for Europe.52 Therefore, it is highly likely that many Arab GBMSM – both Muslim and non-Muslims who may be living in or coming from socially conservative environments – also experience HIV and other sexual health-related disparities in developed Western countries.

Early in the review process, it became apparent that research on infectious diseases among Arabs residing in Western countries is generally limited.53,54 Some research conducted within the Arab world indicates that high risk groups, such as GBMSM, have been excluded from HIV surveillance systems.30 Although this exclusion can largely be explained by the widespread denial of the existence of homosexual relationships and HIV infections in that part of the world,55 it does not, however, explain the scarcity of research pertaining to Arab GBMSM’s access to HIV and other sexual health services in the developed West.

Barriers to research and recruitment

Challenges related to participant recruitment, including factors such as social stigma, cultural barriers, and limited representation within existing networks, contribute to the complexities encountered in conducting research on Arab GBMSM. Data from the Arab world reveals that it is common practice for gay men to conceal their identities and sexual practices from healthcare providers within their socially conservative communities.55 In these contexts, if they are perceived as anything other than heterosexual and/or to potentially be living with HIV, a great deal of shame and disgrace would be placed on their families by the wider Arab community. In many Arab cultures, this is exacerbated by unfavourable wider Arab community labels of homosexuality as a ‘sin’ or haram, meaning ‘forbidden’.22,23

The concealment of sexual identities and practices from healthcare providers is a phenomenon that likely transcends borders, persisting not only within the Arab world but also extending to developed Western contexts. Further, factors such as the illegality of same-sex relationships in many of their Arab ancestral countries, significant discrimination and social pressure fuelled by lack of exposure and awareness, societal and familial norms, religious and cultural factors, and associated perceptions of gender and sexuality, may also contribute to a reluctance of Arab GBMSM to acknowledge their sexuality, let alone discuss such topics with researchers.24–26 The authors from the one study that met the inclusion criteria for our review did indeed reinforce a common understanding of confidentiality as an important factor in accessing HIV and other sexual health services for some populations of gay men.50 This echoed Evans’ et al.56 findings that some populations of gay men are generally harder to reach for research purposes and are more likely to provide sexual information, if any, through online or electronic devices than during in-person or face-to-face interactions. Additionally, it is plausible that researchers of Arab descent may have concerns about potential repercussions or backlash for themselves from their own Arab communities when conducting research on this topic. Fears of being identified (or ‘outed’) and/or facing experiences of homophobia or vilification themselves may further contribute to the scarcity of this research.

Inadequate data collection efforts

Insufficient attention and effort directed towards comprehensive data collection methods have contributed to the dearth of information regarding the experiences of Arab GBMSM in sexual health research studies. Arab ethnicities have often been underrepresented, misclassified, or at times pigeonholed into the ‘White’, or ‘Other’ racial category in Western data collection efforts57 and are, therefore, undercounted. For example, historically in the US, early migrants from Lebanon and Syria fought to be considered as ‘White’ in order to be accorded citizenship and land ownership rights.58 Ajrouch and Jamal59 found that Lebanese and Syrians, as well as Christian Arabs, were still more likely to check ‘White’ on a racial demographic form and be less comfortable self-identifying as ‘Arab American’ compared to, for example, Yeminis and Iraqis. This dissociation for some from their Arab identities can be attributed to many migrant and ethnic minority Arabs, including GBMSM, feeling disenfranchised due to their experiences of prolonged and systemic racism.60 This added complexity of a lack of granularity in racial categorisation, observed in various contexts, such as census data, health forms, and research surveys, may have resulted in a failure to capture key information specifically related to Arab GBMSM.

Conclusion

The scarcity of research on access to HIV and sexual health services for Arab GBMSM in developed Western countries highlights the pressing need to examine this demographic within the broader GBMSM population. Although some subgroups have received attention, Arab men remain relatively understudied and underrepresented within research, despite likely constituting a meaningful portion of both the diasporic Arab and GBMSM populations.

Given the aforementioned limitations of existing research on this population, recruitment challenges, and poor data collection efforts, it is imperative that researchers, policy makers, and health organisations take immediate action. These concerns necessitate a concerted effort to address the unique needs of underrepresented populations, including Arab GBMSM, within the realm of HIV and sexual health research in the developed West. By actively engaging in rigorous research that elucidates their distinct experiences and health needs, we can better understand the influence of intersecting factors, such as sexuality, race, culture, religion, socio-economic status, language barriers, immigration status, and health literacy on the health of underrepresented populations of GBMSM. Further, we can inform evidence-based interventions, enhance access to tailored healthcare services, and foster health equity to comprehensively address the multifaceted challenges faced by these communities. Finally, prioritising investments in diverse research teams, implementing inclusive data collection methodologies, and cultivating supportive environments for participation are pivotal steps towards achieving meaningful representations and optimising HIV and other sexual health outcomes for all other hidden populations that remain absent from the literature. Failure to address this gap leaves populations, such as Arab GBMSM, at risk of being hidden and excluded during data collection, policy formulation, and health promotion efforts within developed Western contexts.

Data availability

The data that supports this study are available in the article and accompanying online Supplementary material.

Author contributions

BS conceptualised and formulated the paper. BS, MH, MK, and GP systematically screened the search results for relevant articles. BS and MH finalised the decision regarding the included articles. BS prepared and drafted the manuscript. GP, LM, NW, and MK reviewed the manuscript. MH, LM, MK, and GP supervised the project and contributed to revising and providing feedback on the manuscript. BS prepared and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

References

1 Kirby T. The Kirby Institute—ending HIV transmission in Australia. Lancet HIV 2022; 9(7): e462.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

2 NSW Ministry of Health. NSW HIV strategy 2021–2025. Health CfP; 2021. Available at https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/endinghiv/Publications/nsw-hiv-strategy-2021-2025.pdf

3 Australian Government, Department of Health. Eighth national EIGHTH HIV strategy. Department of Health; 2018. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2022/06/eighth-national-hiv-strategy-2018-2022.pdf

4 Nicholls EJ, Samba P, McCabe L, et al. Experiences of and attitudes towards HIV testing for Asian, Black and Latin American men who have sex with men (MSM) in the SELPHI (HIV Self-Testing Public Health Intervention) randomized controlled trial in England and Wales: implications for HIV self-testing. BMC Public Health 2022; 22(1): 809.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

5 Phillips TR, Medland N, Chow EPF, et al. Newly arrived Asian-born gay men in Australia: exploring men’s HIV knowledge, attitudes, prevention strategies and facilitators toward safer sexual practices. BMC Infect Dis 2022; 22(1): 209.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

6 Pacheco M, Warfield SK, Hatzistavrakis P, et al. “I don’t see myself represented:” Strategies and considerations for engaging gay male Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander teens in research and HIV prevention services. AIDS Behav 2023; 27(4): 1055-1067.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

7 Boone CA, Bowleg L. Structuring sexual pleasure: equitable access to biomedical HIV prevention for Black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health 2020; 110(2): 157-159.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

8 Kobrak P, Ponce R, Zielony R. New arrivals to New York City: vulnerability to HIV among urban migrant young gay men. Arch Sex Behav 2015; 44(7): 2041-2053.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

9 Phillips TR, Medland N, Chow EPF, et al. “Moving from one environment to another, it doesn’t automatically change everything”. Exploring the transnational experience of Asian-born gay and bisexual men who have sex with men newly arrived in Australia. PLoS ONE 2020; 15(11): e0242788.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

10 Warren JC, Fernández MI, Harper GW, Hidalgo MA, Jamil OB, Torres RS. Predictors of unprotected sex among young sexually active African American, Hispanic, and White MSM: the importance of ethnicity and culture. AIDS Behav 2008; 12(3): 459-468.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

11 Gunaratnam P, Heywood AE, McGregor S, et al. HIV diagnoses in migrant populations in Australia—a changing epidemiology. PLoS ONE 2019; 14(2): e0212268.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

12 Medland NA, Chow EPF, Read THR, et al. Incident HIV infection has fallen rapidly in men who have sex with men in Melbourne, Australia (2013–2017) but not in the newly-arrived Asian-born. BMC Infect Dis 2018; 18(1): 410.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

13 The World Bank. Arab World. Available at https://data.worldbank.org/region/arab-world [accessed 02 March 2022]

14 Statistics Canada. Immigration and ethnocultural diversity highlight tables: data tables. Available at https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/imm/Table.cfm?Lang=E&T=41&Geo=00&SP=1&vismin=8&age=1&sex=1 [accessed 03 May 2022]

15 Pew Research Center. Arab-American population growth. Available at https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2012/11/28/arabamerican-population-growth/[accessed 05 May 2022]

16 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Data from: cultural diversity: census. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2021. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/cultural-diversity-census/latest-release#:~:text=27.6%20per%20cent%20of%20the,Punjabi%20(0.9%20per%20cent)

17 Crumley B. Should France count its minority population? Time; 24 March 2009. Available at http://content.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1887106,00.html

18 Statista DE. Anzahl der Ausländer in Deutschland nach Herkunftsland von 2019 bis 2021. Available at https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1221/umfrage/anzahl-der-auslaender-in-deutschland-nach-herkunftsland/

19 Tutt Italia. Cittadini Stranieri 2020. Available at https://www.tuttitalia.it/statistiche/cittadini-stranieri-2020/ [accessed 5 March 2022]

20 Alessi EJ, Kahn S, Greenfield B, Woolner L, Manning D. A qualitative exploration of the integration experiences of LGBTQ refugees who fled from the Middle East, North Africa, and Central and South Asia to Austria and the Netherlands. Sex Res Soc Policy 2020; 17(1): 13-26.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

21 Alessi EJ, Kahn S, Woolner L, Van Der Horn R. Traumatic stress among sexual and gender minority refugees from the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia who fled to the European Union. J Trauma Stress 2018; 31(6): 805-815.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

22 Cense M. Sexual discourses and strategies among minority ethnic youth in the Netherlands. Cult Health Sex 2014; 16(7): 835-849.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

23 Sanjakdar F. Participatory action research: creating spaces for beginning conversations in sexual health education for young Australian Muslims. Educ Act Res 2009; 17(2): 259-275.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

24 Abboud S, Naal H, Chahine A, Taha S, Harfouch O, Mahmoud H. “It’s mainly the fear of getting hurt”: experiences of LGBT individuals with the healthcare system in Lebanon. Ann LGBTQ Publ Popul Health 2020; 1(3): 165-185.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

25 Awada G. Homosexuality legalization in Arab countries: a shifting paradigm or a wake-up call. J Soc Pol Sci 2019; 2(2): 320-332.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

26 Michli S, Jamil FE. Internalized homonegativity and the challenges of having same-sex desires in the Lebanese context: a study examining risk and protective factors. J Homosex 2022; 69(1): 75-100.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

27 Kteily-Hawa R, Hawa AC, Gogolishvili D, et al. Understanding the epidemiological HIV risk factors and underlying risk context for youth residing in or originating from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region: a scoping review of the literature. PLoS ONE 2022; 17(1): e0260935.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

28 Ballouz T, Gebara N, Rizk N. HIV-related stigma among health-care workers in the MENA region. Lancet HIV 2020; 7(5): e311-e313.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

29 Memish ZA, Filemban SM, Bamgboyel A, Al Hakeem RF, Elrashied SM, Al-Tawfiq JA. Knowledge and attitudes of doctors toward people living with HIV/AIDS in Saudi Arabia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 69(1): 61-67.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

30 Mumtaz GR, Hilmi N, Majed EZ, Abu-Raddad LJ. Characterising HIV/AIDS knowledge and attitudes in the Middle East and North Africa: systematic review and data synthesis. Glob Publ Health 2020; 15(2): 275-298.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

31 Obermeyer CM. HIV in the Middle East. BMJ 2006; 333(7573): 851-854.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

32 Clark KA, Keene DE, Pachankis JE, Fattal O, Rizk N, Khoshnood K. A qualitative analysis of multi-level barriers to HIV testing among women in Lebanon. Cult Health Sex 2017; 19(9): 996-1010.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

33 Wagner GJ, Aunon FM, Rana Y, Khouri D, Mokhbat J. Relationship between comfort with and disclosure about sexual orientation on HIV-related risk behaviours and HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Beirut, Lebanon. J Int AIDS Soc 2012; 15(suppl. 3): 188-189.

| Google Scholar |

34 Ikizler AS, Szymanski DM. A qualitative study of Middle Eastern/Arab American sexual minority identity development. J LGBT Issues Couns 2014; 8(2): 206-241.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

36 Wuestenenk N, van Tubergen F, Stark TH. Attitudes towards homosexuality among ethnic majority and minority adolescents in Western Europe: the role of ethnic classroom composition. Int J Intercult Relat 2022; 88: 133-147.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

37 Smerecnik C, Schaalma H, Gerjo K, Meijer S, Poelman J. An exploratory study of Muslim adolescents’ views on sexuality: implications for sex education and prevention. BMC Public Health 2010; 10(1): 533.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

38 Shteyman J. Mark Latham slammed for homophobic tweet at fellow MP. AAP General News Wire. 2023. Available at https://www.proquest.com/wire-feeds/mark-latham-slammed-homophobic-tweet-at-fellow-mp/docview/2792202989/se-2?accountid=17095

40 Targeted News Service. ‘No longer alone’: LGBT voices from Middle East, North Africa. Targeted News Service; 2018. Available at https://www.proquest.com/wire-feeds/no-longer-alone-lgbt-voices-middle-east-north/docview/2025814015/se-2?accountid=17095

41 Boussalem A, Di Feliciantonio C. ‘Like a piece of meat in a pack of wolves’: gay/bisexual men and sexual racialization. Gender Place Cult 2023; 1-18 10.1080/0966369X.2023.2200579.

| Google Scholar |

42 Lessard D, Lebouché B, Engler K, Thomas R. An analysis of socio-demographic and behavioural factors among immigrant MSM in Montreal from an HIV-testing site sample. Can J Hum Sex 2016; 25(1): 53-60.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

44 Hayek SE, Kassir G, Cherro M, et al. Mental health of LGBTQ individuals who are Arab or of an Arab descent: a systematic review. J Homosex 2023; 70: 2439–2461. 10.1080/00918369.2022.2060624

45 Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018; 18(1): 143.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

46 Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Int Med 2018; 169(7): 467-473.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

47 Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method 2005; 8(1): 19-32.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

49 Wong JP-H, Macpherson F, Vahabi M, Li A. Understanding the sexuality and sexual health of Muslim young people in Canada and other Western countries: a scoping review of research literature. Can J Hum Sex 2017; 26: 1 48-59.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

50 Lessard D, Lebouche B, Engler K, Thomas R, Machouf N. Explaining the appeal for immigrant men who have sex with men of a community-based rapid HIV-testing site in Montreal (Actuel sur Rue). AIDS Care 2015; 27(9): 1098-1103.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

53 Harfouch O, German D. The absence of middle Eastern and North African sexual and gender minority Americans from health research. LGBT Health 2018; 5(5): 330-331.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

54 Sweileh WM. Global research output in the health of international Arab migrants (1988–2017). BMC Public Health 2018; 18(1): 755.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

55 Shawky S, Soliman C, Kassak KM, Oraby D, El-Khoury D, Kabore I. HIV surveillance and epidemic profile in the Middle East and North Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009; 51: S83-S95.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

56 Evans AR, Hart GJ, Mole R, et al. Central and East European migrant men who have sex with men in London: a comparison of recruitment methods. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011; 11(1): 69.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

57 Naber N. Chicagoland study shows why we need a MENA category in The U.S. Census. Chicago Reporter. Available at https://www.chicagoreporter.com/chicagoland-study-shows-why-we-need-a-mena-category-in-the-u-s-census/

58 Awad GH, Hashem H, Nguyen H. Identity and ethnic/racial self-labeling among Americans of Arab or Middle Eastern and North African Descent. Identity 2021; 21(2): 115-130.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

59 Ajrouch KJ, Jamal A. Assimilating to a white identity: the case of Arab Americans. Int Migr Rev 2007; 41(4): 860-879.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

60 Chaney MP, Dubaybo F, Chang CY. Affirmative counseling with LGBTQ+ Arab Americans. J Ment Health Couns 2020; 42(4): 281-302.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |