Reconciling blue spaces: evaluating social equity and justice in state-led Indigenous marine development programs

Jillian E. Conrad A B * , Laura Griffiths A B , Natalie Osborne C , James C. R. Smart A D and Christopher L. J. Frid A B

A B * , Laura Griffiths A B , Natalie Osborne C , James C. R. Smart A D and Christopher L. J. Frid A B

A

B

C

D

Abstract

Government-led Indigenous marine development programs aim to deliver socially equitable outcomes, yet these principles are not always embedded in their design.

Evaluating the extent to which equity is prioritised is crucial for respecting Indigenous rights, interests and advancing reconciliation.

This study introduces the Blue Peacebuilding Scorecard (BPS), a novel quantitative tool to assess social equity integration in marine-based Indigenous programs across Australia, Canada and New Zealand.

New Zealand emerged as a leader in equity and justice, Canadian programs displayed varied performance and Australian programs ranked moderately overall. Justice was a consistently strong category across all nine programs, indicating explicit consideration in program design internationally. Areas such as legacy, access and finance showed moderate performance globally, highlighting opportunities for improvement.

To enhance social equity and advance Indigenous rights within national blue economy development, emphasis should be placed on impact assessment, data sharing and recognising data ownership as critical pathways for progress.

The BPS can be adapted to provide localised insights, fostering reconciliation and collaboration. By facilitating co-learning and reducing both stakeholder conflict and fatigue, the use of this practical tool can lead to enhanced program effectiveness and improved relationships.

Keywords: blue economy, environmental justice, environmental management, Indigenous, marine planning, ocean governance, ocean policy, social equity.

Introduction

Global environmental movements concerning the oceanic domain have escalated social equity as a central development priority. These movements seek to rebalance economic, environmental and social sustainability in ocean spaces, which have historically been dominated, especially in the global west, by exploitation, extraction and profit-seeking. Initiatives such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Goal 14 Life Below Water (see https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal14), the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030) (see https://oceandecade.org/challenges/) and the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (see https://oceanpanel.org/the-agenda/) exemplify this trend towards equity and sustainability. Frameworks in support of environmental sustainability are often deeply intertwined with social imperatives at the national level, as, for example, in adaptations of the Blue Economy development model. These initiatives seek to achieve transformative outcomes for marine social development on the international stage.

In support of an equitable shift, marine social disparities have been mapped through a Blue Economy lens within various nations and across sectors; this has informed the development of the social sustainability agenda (Bennett et al. 2019a; Cisneros-Montemayor et al. 2019, 2022; Issifu et al. 2023; Conrad and Frid, in press). The poor condition of Indigenous rights within ocean and coastal spaces is a recurring theme in the blue justice literature and is an evolution of the equity narrative that highlights injustices resulting from ocean-based economic development. A multitude of issues facing coastal Indigenous communities around the globe include dispossession and ocean grabbing, loss of access and control, power imbalances and exclusions from governance, and Indigenous rights abuses (Kerr et al. 2015; Ban and Frid 2018; Hiriart-Bertrand et al. 2020; Bennett et al. 2021; Wilson 2021). Such inequities are reflected within broader environmental justice literature, which highlights vulnerabilities and inequities experienced by Indigenous communities (Whyte 2018; McGregor et al. 2020; Mitchell et al. 2020; Parsons and Fisher 2022). These challenges can be categorised by justice type into recognitional, procedural and distributive domains outlined and utilised across a wide body of literature (Cutter 1995; G Walker 2009; Bennett et al. 2019b, 2021; Parsons et al. 2021).

Place-based inequities are disparities experienced by individuals or communities because of geographic location. These inequities include unequal access to services, resources and opportunities, which can be further exacerbated by systemic exclusion at the national and international levels. In the context of international ocean governance, these exclusions manifest in the absence of Indigenous perspectives and discussions from Blue Economy and Sustainable Development Goal 14 (SDG 14) initiatives (Conrad and Frid, in press). Absence persists despite it being over 15 years since the adoption of the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which outlines the rights of Indigenous Peoples in international law and policy, complemented by minimum recognition, protection and promotion standards (United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner 2023). The Declaration was initially endorsed by 144 states, with 11 abstentions and 4 oppositional votes (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, see https://social.desa.un.org/issues/indigenous-peoples/united-nations-declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples). The four nations that initially voted against are among the world’s most prominent ocean nations, namely, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States of America. Rationale for initial opposition included concerns over provisions on land and resource rights, self-determination and phrasing that gave Indigenous Peoples a right of veto over state management of resources and national legislation (United Nations 2007). The Declaration was later endorsed by each of these nations, first by Australia in 2009 because of a change of government (Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs 2009), followed by New Zealand and Canada in 2010 (Government of Canada 2010; New Zealand Parliament 2010) and the USA in 2011 (US Department of State 2011).

Each of these four nations have historical and ongoing settler-colonial structures. Colonialism is defined as ‘the policy or practice of acquiring full or partial political control over another country, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically’ (see https://www.google.com/search?q=colonialism). Further examination of Indigenous–settler relations and colonial heritage within each of these nation states highlights clear parallels that are particularly prominent among Australia, Canada and New Zealand (Armitage 1995). These countries’ respective Indigenous social policies find their origins rooted in the ideologies espoused by the 1837 House of Commons Select Committee on Aborigines. Their legal frameworks, all stemming from British common law, display remarkable similarity. Moreover, these three nations have a minority Indigenous population and settler interests remain dominant (Armitage 1995). Modern dynamics between Indigenous and settler communities are shaped by specific factors such as the relative proportions of these populations, geographical features and, in Canada’s case, the influence of additional colonial powers (Armitage 1995; Mitrou et al. 2014). These historical interconnections and place-based evolutions contribute, in somewhat diverse ways, to the enduring inequalities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations (Mitrou et al. 2014). Approaches that have enabled Indigenous Peoples’ marine rights and reconciliation between the colonial state and Indigenous communities have diversified through time within these three countries. Thus, they present useful case studies through which to understand how current Indigenous marine rights and interests are protected and served as a result of state-affirmed practices governing ocean and coastal resources.

State-led Indigenous marine development programs operate in all three countries. Systematic mapping of such programs can address the following two key objectives: (i) identification and comparison of active efforts by governments toward affirming Indigenous rights and interests in ocean and coastal spaces, and (ii) consideration of the extent to which these programs succeed in advancing Indigenous environmental justice in the context of marine environments. Identifying existing barriers to social equity within state-led Indigenous marine development programs is needed to build justice-based blue economies in nations with settler-colonial structures.

Evaluation frameworks employed in diverse fields and geographical areas offer insights into best practices and methodological approaches for assessing Indigenous-focused marine management programs. For example, in the realm of health in the United States, Lawrence and James (2019) crafted the Indigenous Evaluation Framework to assess a federally sponsored initiative addressing chronic disease prevention in Indian Country. This framework underscores Indigenous core values and knowledge, addressing a historical backdrop of mistrust between tribal communities and the federal government concerning evaluation and data-driven practices (Lawrence and James 2019). Similarly, within the field of education, the Indigenous Evaluation Framework (IEF) places Indigenous wisdom at the forefront, emphasising the reclamation of power and challenging the notion that the Western evaluation framework is the sole valuable framework (Velez et al. 2022).

Building on this foundational work, our novel Blue Peacebuilding Scorecard (BPS) extends these insights into the field of ocean and coastal management by offering a specialised tool to evaluate Indigenous marine governance programs, with a focus on equity, justice and the integration of Indigenous priorities in the marine space. The BPS, developed by the authorship team, addresses the unique complexities and needs of Indigenous communities within marine governance and fills critical gaps left by existing frameworks.

The BPS allows for the systematic comparison of various equity categories in practical marine programs. Scorecard approaches are widely recognised tools for strategic planning, monitoring and enhancing accountability (Keleher 2013). They have proven effective in supporting policymaking across public sectors (WE Walker 2000) and have been utilised to evaluate environmental and social governance policies in diverse contexts (Chai 2009; Berke et al. 2019). Drawing on insights from environmental justice, social equity and sustainability studies (Liu 2007; Timko and Satterfield 2008), the BPS was designed by the authorship team to advance understanding of marine social equity and Indigenous rights within state-led efforts to decolonise, reconcile and promote peace moving forward.

The study was guided by the following research questions:

What are the key principles and components of the Blue Peacebuilding Scorecard (BPS), and how does it offer a new methodological approach for assessing equity in Indigenous marine development programs?

How do state-led Indigenous marine development programs in Australia, Canada and New Zealand perform against the equity criteria established by the BPS?

Which program elements identified through the BPS should be prioritised to strengthen equity in future marine development policies and initiatives?

Materials and methods

Case studies of Australia, Canada and New Zealand were chosen due to their shared characteristics in Indigenous affairs, including eventual support for UNDRIP, colonial heritage, governance structures and the dynamics of Indigenous–settler relationships (see ‘Case study site selection’ section). We conducted a comprehensive scan of digital federal government resources from each nation to identify state-led Indigenous marine development programs. These resources encompassed legislation, high-level policies, departmental agendas and broader marine governance initiatives.

Australian programs were identified through the environment management projects of the National Indigenous Australians Agency, three of which included a marine focus (National Indigenous Australians Agency 2023). In Canada, three active programs were sourced from governance and reconciliation efforts under Canada’s Oceans Agenda (Fisheries and Oceans Canada 2023). The New Zealand context presented a more dispersed landscape, with programs being selected from multiple government branches overseeing Māori1 ocean and coastal rights, including the Ministry for the Environment, Te Ohu Kai Moana Trustee Limited (Te Ohu Kaimoana, see https://www.teohukaimoana.nz/about-us) and Te Arawhiti, the Office for Māori Crown Relations (Te Arawhiti 2022). Program documents such as reports, articles and reviews were scrutinised by individual work to determine scores.

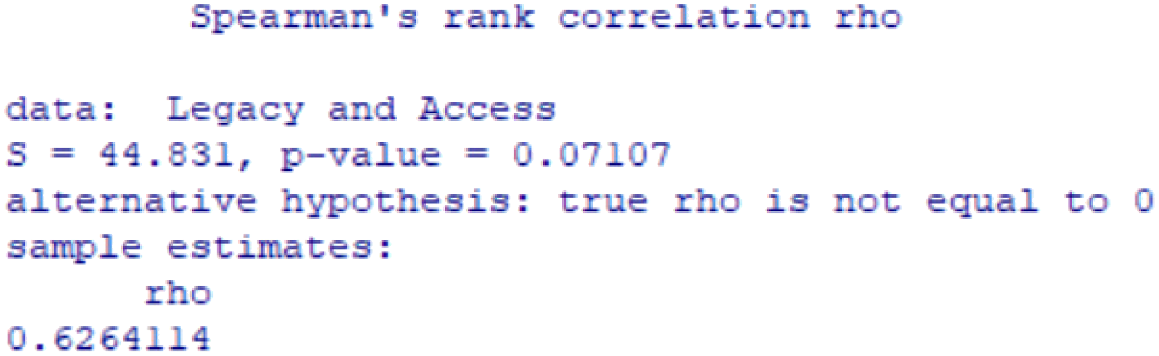

The Blue Peacebuilding Scorecard (BPS) (Fig. 1) was developed as an evaluative tool to assess equity in state-led Indigenous marine management programs across the three nations. Drawing on concepts from social equity and justice literature, general management evaluation models and foregrounding peacebuilding work by Conrad and Frid (2025), the BPS integrates performance management indicators to enable a quantitative comparison of program effectiveness. Each program was assessed by the authorship team across six equity categories (justice, impact, data, finance, legacy and access), evaluated on the basis of three criteria (A, B, C) reflecting increasing levels of specificity. Scores ranged from 0 (missing information) to 5 (advanced specificity), with additional points awarded for comprehensive coverage across all criteria. Program documents were scrutinised to determine scores, adjusted to account for ongoing program developments and data availability as of early 2024. In some instances, data were limited for certain criteria as consultation processes were ongoing. We addressed this by scanning for updated program information 3 months following the initial assessment period; where consultations remain ongoing, such as in the case of Australia’s Aboriginal Water Entitlements Program, a further re-evaluation could be conducted following this period (National Indigenous Australians Agency 2023).

The Blue Peacebuilding Scorecard (BPS), developed by the authors, was used to evaluate three state-led Indigenous-focused marine management programs in Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Six categories were initially scored on the basis of criteria of increasing complexity: 0 is missing (no information related to the category), 1 is fundamental (Criterion A: broad, general information), 3 is intermediate (Criterion B: moderately specific information), and 5 is advanced (Criterion C: highly specific information). Category scores were adjusted to 10 when all criteria were fulfilled. Programs meeting all criteria received a total score of 60. The Australian Indigenous Rangers Program evaluation is shown as an exemplar. See Table 1 for further information.

| Category | Justification | Criteria | Information retrieval within relevant documents | Points | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Justice | The inclusion of justice allows for the quantification of equity and fairness. It enables ethical, human rights-based governance and reduces disparities experienced by marginalised and vulnerable populations. | Recognitional | Criteria were established and assessed for their alignment with the Indigenous Environmental Justice Framework (IEJF) (Conrad and Frid, in press), and scores were assigned accordingly. The IEJF highlights the need for not only acknowledging Indigenous rights (recognitional) and including Indigenous voices in decision-making (procedural) but also ensuring tangible outcomes (distributive) that improve environmental and socio-economic conditions for Indigenous communities. These justice types are progressive and cumulative, with distributive justice representing a more advanced stage that depends on the foundations of recognitional and procedural justice. | 1 | |

| Procedural | 3 | ||||

| Distributive | 5 | ||||

| Impact | Impact assessment provides an understanding of program outcomes and progress toward achieving its intended goal. It also enables identification of unintended consequences to inform refinements and contributes to transparency and accountability by providing concrete evidence of their effectiveness. Impact assessment can also guide evidence-based decision-making. | Disaggregated statistics | Statistics, such as the number of communities involved and jobs generated, in relation to specific programs, areas, etc., that showcase a commitment to understanding and addressing disparities within specific subgroups and ensuring equity in program outcomes. | 1 | |

| General impact statements, details and assessments | Clear and detailed reports that outline the program’s influence, highlighting specific achievements and offering assessments that gauge its effectiveness in meeting its intended goals. Details such as specific impact actions, assessments, participant statements and reported benefits were included. | 3 | |||

| Measurement of the program impact on improving the social, economic and cultural well-being | Explicit details on measurement methodologies, key performance indicators and evidence of positive outcomes that contribute to the overall well-being of the communities involved, specifically regarding social impact, cultural connections and economic benefits. This was identified through program reporting, stories from participants and other similar document types. | 5 | |||

| Data | Robust data collection enables measurement of program inputs, outputs and outcomes, facilitating evidence-based decision-making. Data collection enhances comparability across various programs and jurisdictions and enables the identification of trends, patterns and areas for improvement. | Collection or analysis of relevant data and indicators to assess progress and outcomes | Evidence of a structured approach to data collection, including the selection of meaningful indicators and a clear methodology for assessing the program impact and effectiveness over time. This includes but is not limited to measurement and tracking tools, frameworks, datasets, regular data and progress reporting, individual project reviews. | 1 | |

| Culturally sensitive data retrieval and handling | References to culturally sensitive approaches in data collection, storage and dissemination, ensuring that Indigenous perspectives are considered and respected throughout the process. This includes data retrieved and handled by and for Indigenous groups, ensuring cultural protocols are adhered to. | 3 | |||

| Transparent and accountable reporting of program results to Indigenous communities and stakeholders | Evidence of regular and comprehensive reporting, detailing the outcomes achieved and the impact on Indigenous communities, fostering an informed and engaged rightsholder and stakeholder base. | 5 | |||

| Finance | Financial transparency ensures that programs are cost-effective, efficient in their use of taxpayer funds and support optimisation of resource allocation. This element also enables stakeholders to understand budget, expenditures and cost-effectiveness. | Budget and total funding | Reviewing documents to ascertain a clear breakdown of budget categories and the overall funding amount dedicated to sustaining the program. | 1 | |

| Disbursement details | Reviewing financial reports and documentation to ensure a detailed account of how funds are distributed, expended, and aligned with the program objectives, including but not limited to geographic distribution, recipient information and the timeline of allocations. | 3 | |||

| Initiatives and opportunities | Explicit mentions of current initiatives, funding opportunities, or collaborative ventures, ensuring rightsholders and stakeholders can easily access and engage with the information. | 5 | |||

| Legacy | Legacy assesses a program’s ability to maintain its impact and effectiveness over time. This is essential to ensure lasting positive influence on the target population. Furthermore, assessing longevity and sustainability helps prevent the premature termination of successful programs because of short-term budget constraints or changes in political priorities. | Adaptive management or next steps | Evidence of iterative planning, responsiveness to changing conditions and a roadmap for the program progression. | 1 | |

| Strategies or plans to ensure sustainability and continuity of the program beyond initial implementation | Comprehensive insights into planned measures, resource allocation and adaptation strategies aimed at ensuring long-term viability of the program. | 3 | |||

| Integration of program activities into existing systems and structures for long-term impact | Explicit details on the strategic alignment, sustainable practices and any documented changes or enhancements to existing systems, such as establishing enduring funding agreements and providing evidence of modifications to existing systems. | 5 | |||

| Access | Access focuses on assessing the program’s reach and inclusivity, ensuring that it effectively reaches the intended beneficiaries. Inclusion of this element is critical because it helps identify any disparities in access to the program benefits across different demographic groups or geographic areas. This also aids in maximising positive impact and promotion of inclusivity within a society. | Accessible language | Reviewing program materials for simplicity, clarity and inclusivity to ensure information is easily comprehensible to a diverse audience. | 1 | |

| Resources in Indigenous language(s) | Inclusion of resources available in Indigenous language(s). | 3 | |||

| Engagement instructions and contact information | Presence of user-friendly instructions and easily accessible contact details to promote effective communication and involvement. | 5 |

Our approach assigns equal weight to each category within the BPS to ensure fairness and avoid biases that may arise from disproportionate weighting. This method underscores the holistic evaluation of marine social equity, recognising the interconnectedness among justice, impact, data, finance, legacy and access. Given the potential ripple effects of changes in one category on others, a balanced assessment is crucial to prevent undue emphasis on any single aspect. Stakeholders typically engage in deliberations on category inclusion and weighting in multi-criteria analyses (Proctor and Drechsler 2006). Future applications of the BPS should prioritise the involvement of Indigenous rightsholders in determining categories and their relative weights, reflecting their critical stake in achieving equity.

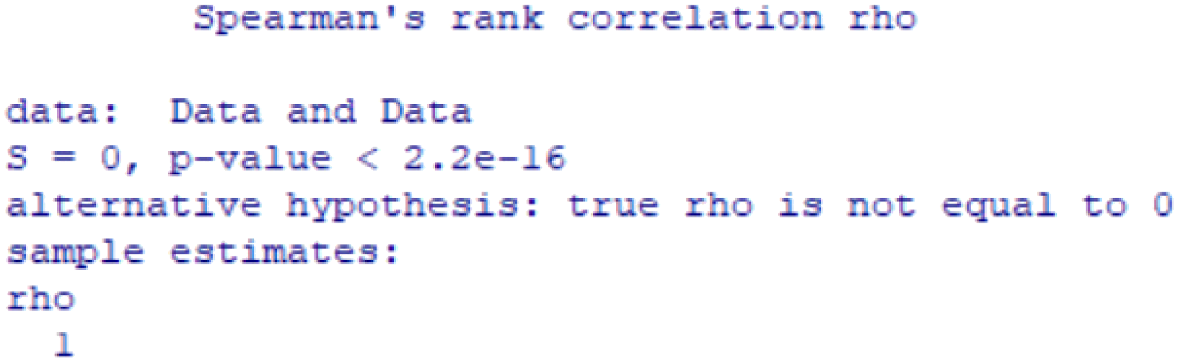

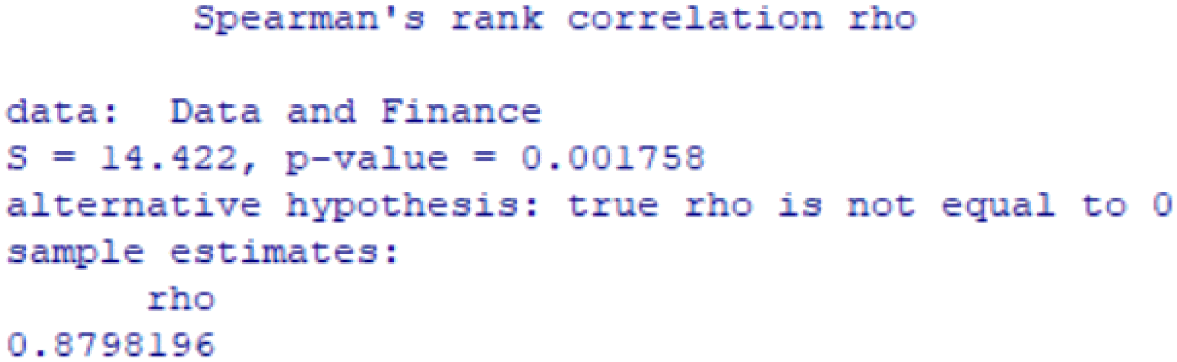

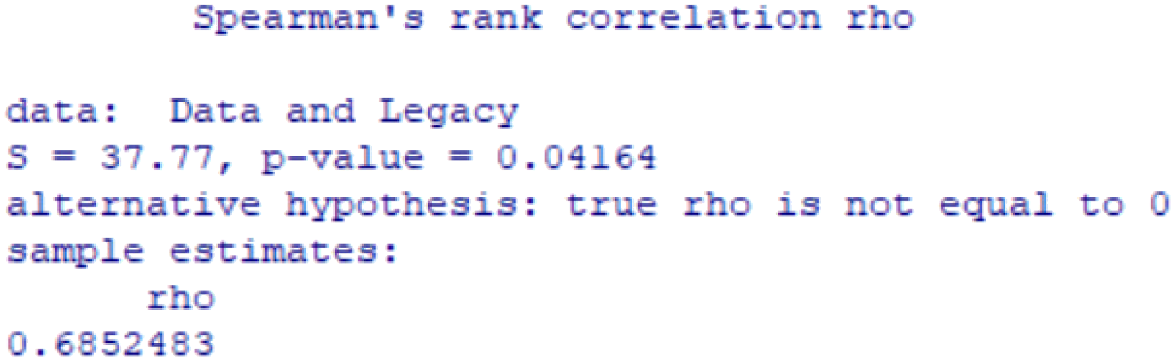

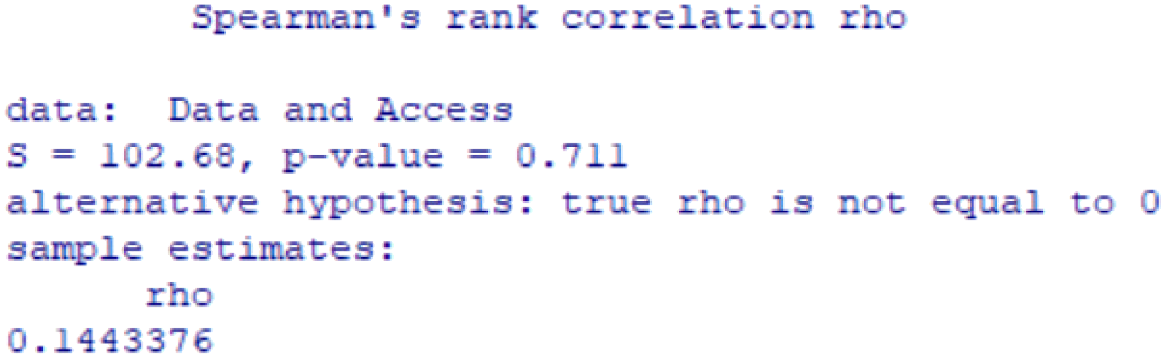

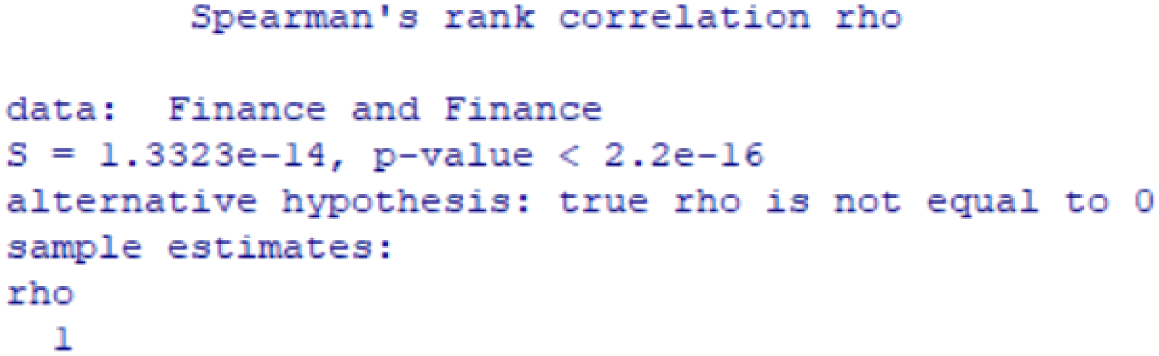

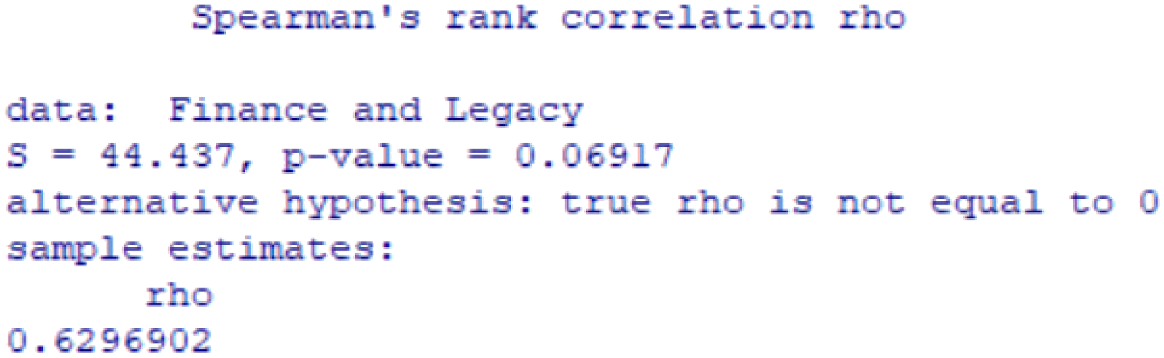

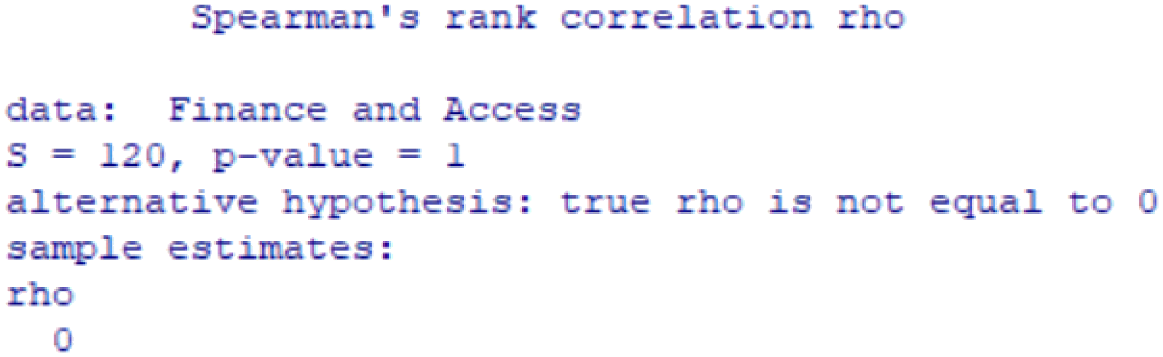

Statistical analysis employed Spearman’s rank correlation tests (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, see https://www.r-project.org/) to identify monotonic rank correlations between program scores. This approach provided insights into program strengths and areas for improvement within national approaches. The programs under analysis are in a continual state of development, with some still in the consultation phase. This is a potential constraint in data availability, underscoring the need to interpret findings with consideration for ongoing consultations and evolving priorities.

Case study site selection

To provide a contextual lens and facilitate the interpretation of findings, the following section delivers a succinct overview of the status of Indigenous rights within each of the study nations. This synopsis is not intended as an exhaustive historical account or a political analysis of colonialism’s intricate interplay within marine domains.

Australia’s First Peoples, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, face ongoing human rights challenges. A report from the Australian Human Rights Commission in 2021 highlighted critical shortcomings in the Australian Federal Government’s approach to implementing UNDRIP. The report found the government had not taken necessary steps to integrate the UNDRIP into legal frameworks, policies and practices, nor had it engaged in dialogue with Indigenous communities to create a National Action Plan aligned with the UNDRIP (Australian Human Rights Commission 2021, p. 1). Furthermore, the report emphasised the absence of audits to ensure existing laws and policies complied with the principles of the UNDRIP (Australian Human Rights Commission 2021, p. 1). The Closing the Gap Strategy, which aimed to realise the objectives of the Declaration, was also critiqued for insufficiently involving Indigenous communities in decision-making processes and setting priorities (Australian Human Rights Commission 2021, p. 1). In response to these challenges, the 2019 National Partnership Agreement on Closing the Gap was established with the goal of transforming the Government’s relationship with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. This initiative aimed to shift towards collaborative definition of goals, outcomes and targets, with a strong emphasis on accountability and reporting (Closing the Gap 2020).

Although constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples is currently lacking, there are ongoing efforts and active steps being taken to address this issue. The Uluru Statement from the Heart is a declaration by Indigenous Australians, expressing the urgent need for constitutional recognition and a representative voice in decision-making processes (see https://ulurustatement.org/the-statement/view-the-statement/). It emphasises the call for a Makarrata Commission to supervise truth telling and reconciliation processes between the Australian Government and Indigenous Peoples. The statement was presented in May 2017 during the First Nations National Constitutional Convention at Uluru; however, it was rejected later that year. The 2022 federal election gave the Uluru Statement renewed momentum within government, as Prime Minister Anthony Albanese pledged to its implementation. The proposed first step was an advisory body, the ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice’, to Federal Parliament (Mills et al. 2023). This proposal was recently rejected by a national referendum in October 2023 (60% vote against; Australian Electoral Commission 2023).

Currently, the National Indigenous Australians Agency, established in 2019, serves as an important platform for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ representation and self-determination. With a focus on 16 priority areas for development, the Agency advances programs aimed at environmental management across terrestrial and marine domains, which seek to promote environmental conservation, cultural preservation and economic empowerment for Indigenous Australians. These include the following three programs analysed in this research (National Indigenous Australians Agency 2023):

‘Sea Country Indigenous Protected Areas Program’ (SCIPAP), which aims to create opportunities for Indigenous Australians and protect coastal and marine areas.

‘Indigenous Ranger Programs’ (IRP) that support Indigenous Australians in managing terrestrial and marine spaces by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander goals.

‘Aboriginal Water Entitlements Program’ (AWEP), which aims to improve surface water access and address historical challenges.

Canada’s multifaceted approach to reconciliation and Indigenous rights encompasses legal enactments, historical treaties, ongoing negotiations and collaborative programs. The recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ rights extends beyond customary law, as the nation has established a comprehensive legal and policy framework. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (see https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/U-2.2/) was enacted in 2021, marking a significant step toward implementing the Declaration at the federal level and rejuvenating the relationship between the Government of Canada and Indigenous Peoples (Government of Canada 2021a). Indigenous Peoples in Canada are recognised and affirmed in Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, of which reconciliation is a fundamental purpose (see https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/const/index.html).

Canada’s historical and modern treaties serve as foundational documents that shape its relationship with Indigenous nations.

Although initial interactions between Indigenous nations and colonial governments were based on mutual respect and collaboration, subsequent colonial and paternalistic policies eroded these relationships, leading to a legacy of colonisation. Recognising this history, Canada has embarked on a journey of reconciliation aimed at addressing the deep-seated impacts of colonialism (Government of Canada 2023a). The ongoing process of reconciliation involves various elements, including existing treaties, land claims negotiations and initiatives such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. To guide its approach, Canada has developed 10 guiding principles that underpin its relationship with Indigenous Peoples. These principles emphasise self-determination, meaningful engagement, respect for agreements, reconciliation and the importance of free, prior and informed consent (Government of Canada 2021b).

The commitment to reconciliation is evident across government departments and is bolstered by departmental reconciliation plans. Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), entrusted with managing fisheries and ocean resources as well as safeguarding Canadian waters, has incorporated governance and reconciliation into its Oceans Agenda. The Agenda underscores the national commitment to improving oceans governance, while fostering collaboration and partnership with Indigenous communities (Fisheries and Oceans Canada 2023, s. 4). Within this framework, the following three ongoing programs have been identified for inclusion in this research (Fisheries and Oceans Canada 2023, s. 4):

‘Aboriginal Fisheries’ (AF), which supports and promotes commercial fishing and conservation activities.

‘Marine Spatial Planning’ (MSP), which is focused on coordinating the use and management of marine spaces.

‘Oceans Protection Plan’ (OPP), which is dedicated to the protection, restoration and preservation of Canadian waters, while also fostering economic growth.

These marine development initiatives are interconnected with broader national programs that emphasise system integration and nation-to-nation governance (NtNG). NtNG aims to address past injustices and foster a mutually respectful and cooperative relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples. It affirms that the relationship between Indigenous Nations and Peoples and the Crown and Canadian governments is based on mutual recognition, respect, responsibility and sharing (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2020). Mechanisms are in place to accommodate Indigenous groups regarding government activities that may affect Indigenous rights, exemplified by the duty to consult (Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada 2021).

New Zealand’s commitment to actualising the UNDRIP has gained momentum with the recent establishment of a Declaration plan, aimed at assessing progress in regular operations (Te Puni Kōkiri 2022). This plan outlines a clear national dedication to the Declaration’s principles, fostering governmental coherence and driving equitable outcomes for Māori, New Zealand’s Indigenous People (Te Puni Kōkiri 2022). Although New Zealand lacks a unified constitutional document, the Treaty of Waitangi stands as the pivotal agreement between the British Crown and ~540 Māori rangatira (chiefs), which formed the foundation of the nation during colonisation. The Treaty’s three articles encompass matters of sovereignty and governance, land and property rights, as well as citizen rights. However, translation challenges have led to varying interpretations of these articles, adding complexity to their implications (Waitangi Tribunal 2016). State-driven reconciliation efforts in New Zealand are multifaceted and have included formal apologies for treaty breaches, such as The Ngāi Tahu Settlement, along with recognition and reparations (Sullivan 2016).

In the realm of marine management, historical adherence to the provisions of the Treaty of Waitangi has been questioned, contributing to degradation of marine ecosystems (Waitangi Tribunal 2011). Critiques from iwi (extended kinship groups) have urged the re-establishment of the relationship between environment and economy. Responding to these concerns at least in the science sector, the government established the National Science Challenge in 2014 (Le Heron et al. 2020). The initiative encompassed 75 research projects conducted between 2014 and 2023 and categorised each into one of the following four strands to find gaps: (1) enhancing the blue economy, (2) refining decision-making by ecosystem-based management (EBM), (3) evaluating the research process, and (4) empowering Mana Moana (Sustainable Seas National Science Challenge 2023). Findings from this research are expected in 2024 and should help inform co-creation and co-management planning.

In essence, New Zealand’s pursuit of UNDRIP alignment and reconciliation efforts is reflected through policy frameworks, legislative mechanisms and research initiatives aimed at safeguarding Indigenous rights, revitalising marine environments, and promoting sustainable management practices. The development programs analysed in this research are as follows:

‘Te Ohu Kaimoana (the Māori Fisheries Trust)’, which emerged from the Treaty of Waitangi (Fisheries Claims) Settlement Act 1992 (see https://teohu.maori.nz/who-we-are/).

‘Te Kāhui Takutai Moana (Marine and Coastal Area)’, enshrining recognition of iwi, hapū and whānau customary interests through the Te Takutai Moana Act 2011 and Ngā Rohe Moana o Ngā Hapū o Ngāti Porou Act 2019 (the takutai moana legislation) (Te Arawhiti 2022).

‘Mana Whakahono ā Rohe: Iwi Participation Arrangements’, a tool operating under the Resource Management Act (RMA) (Ministry for the Environment 2023).

Results

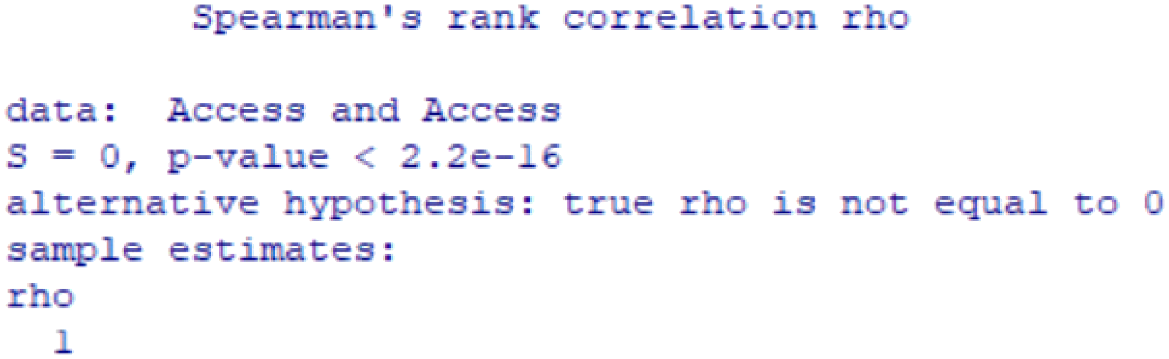

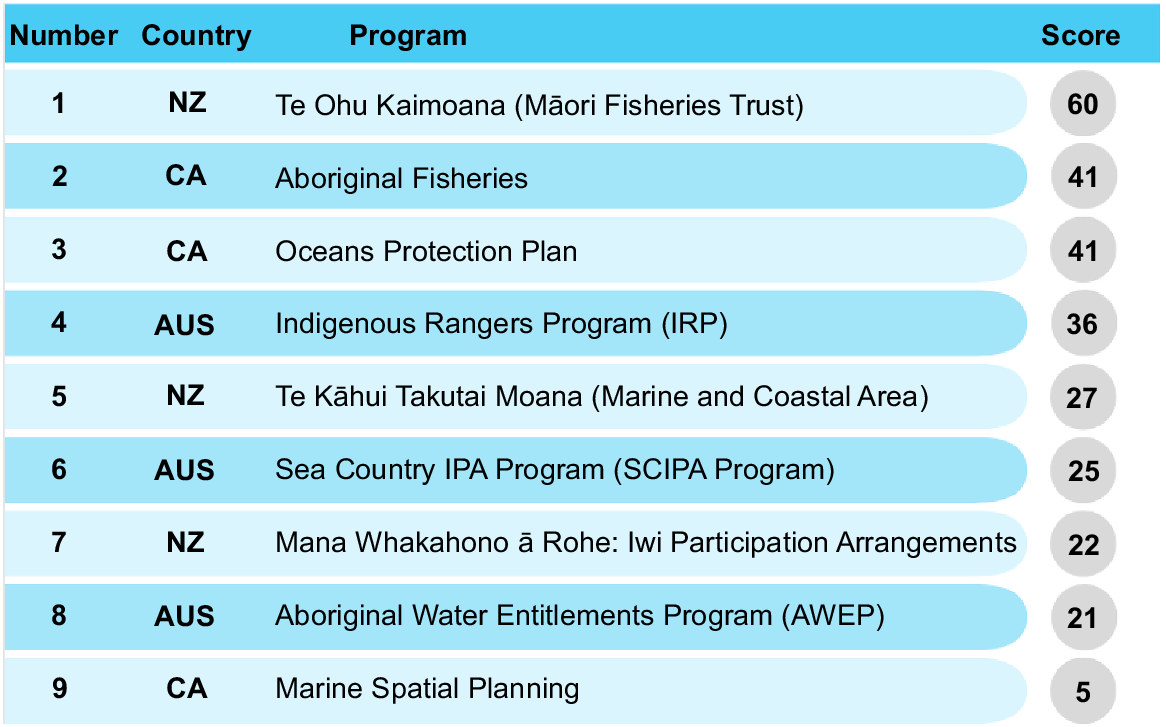

New Zealand achieved the highest aggregate national BPS score, with 109 points of a possible 180. Canada and Australia presented similar aggregate scores that fell ~15% below New Zealand’s tally, totalling 87 and 82 respectively. A detailed examination of individual program rankings showed that New Zealand’s ‘Te Ohu Kaimoana (Māori Fisheries Trust)’ program obtained the highest achievable score of 60 points (Fig. 2). This contrasts with New Zealand’s ‘Mana Whakahono ā Rohe: Iwi Participation Arrangements’ program, which ranked seventh overall. Canada achieved the second and third overall rankings through the ‘Aboriginal Fisheries and Oceans Protection Plan’ programs. The lowest overall ranking program was Canada’s ‘Marine Spatial Planning’ initiative, which achieved a total of only five points. Australian programs were mid to low range, where the ‘Indigenous Rangers Program’ ranked fourth with 36 points, the ‘Sea Country IPA Program’ ranked sixth with 25 points, and the ‘Aboriginal Water Entitlements Program’ ranked eighth with 21 points. Overall, New Zealand’s programs demonstrated the highest intranational BPS variance with a range of 38 points, followed by Canada with a comparable range of 36, and Australia with a range of 15 points. Thus, Australia’s programs were consistently moderate in performance, whereas New Zealand and Canada had some excellent and weak performers.

BPS scores for each of the three analysed national Indigenous-focused marine management programs in Australia (AUS), Canada (CA) and New Zealand (NZ). Scores were determined using the Blue Peacebuilding Scorecard (Fig. 1). See Materials and methods for details.

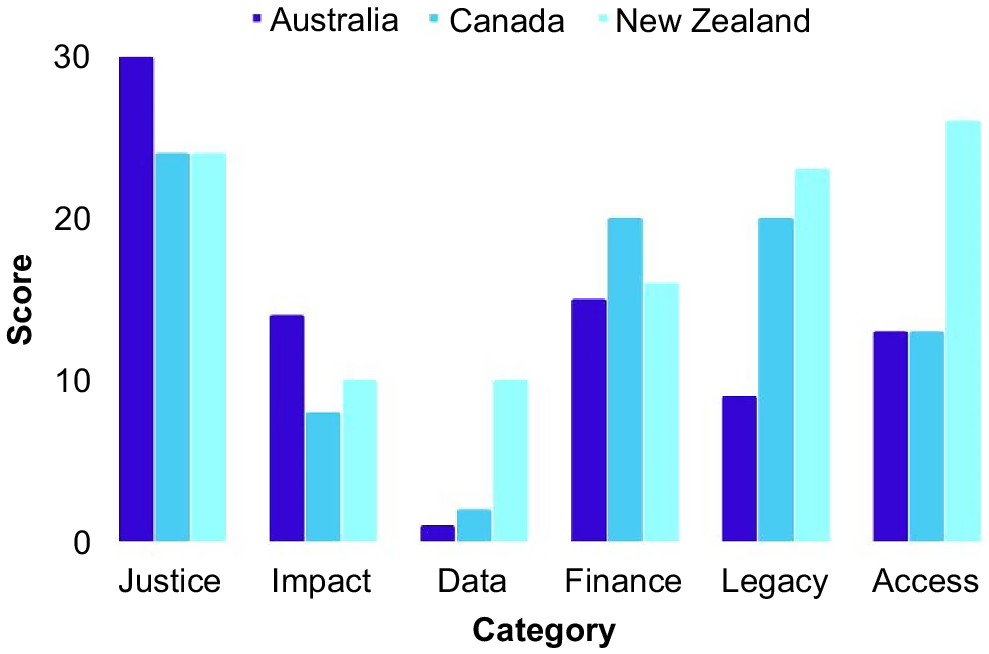

National BPS scores were analysed by category with their respective maximum values (Appendix 1). The resulting proportions showed that programs performed most strongly in terms of justice at 87%, followed by medium performance across the access (58%), legacy (58%) and finance (57%), and low performance across impact (36%) and data categories (14%) (Fig. 3). New Zealand emerged with the highest overall aggregate BPS score, with top national aggregate scores across data, legacy and access categories. Additionally, it secured the second-highest aggregate scores in impact and finance. Canada obtained the highest national aggregate score in the finance category, ranked second in data and legacy and lagged in the impact category. Canada and New Zealand achieved the same aggregate justice scores, whereas Canada and Australia achieved the same aggregate access scores. Australia outperformed both Canada and New Zealand in the justice and impact categories but ranked third in the data, financial and legacy categories.

National BPS scores by category of state-led Indigenous-focused marine management programs in Australia (dark blue bars), Canada (medium blue bars), and New Zealand (light blue bars). Program scores across the six categories of justice, impact, data, finance, legacy and access were determined using the Blue Peacebuilding Scorecard (Fig. 1). See Materials and methods for details.

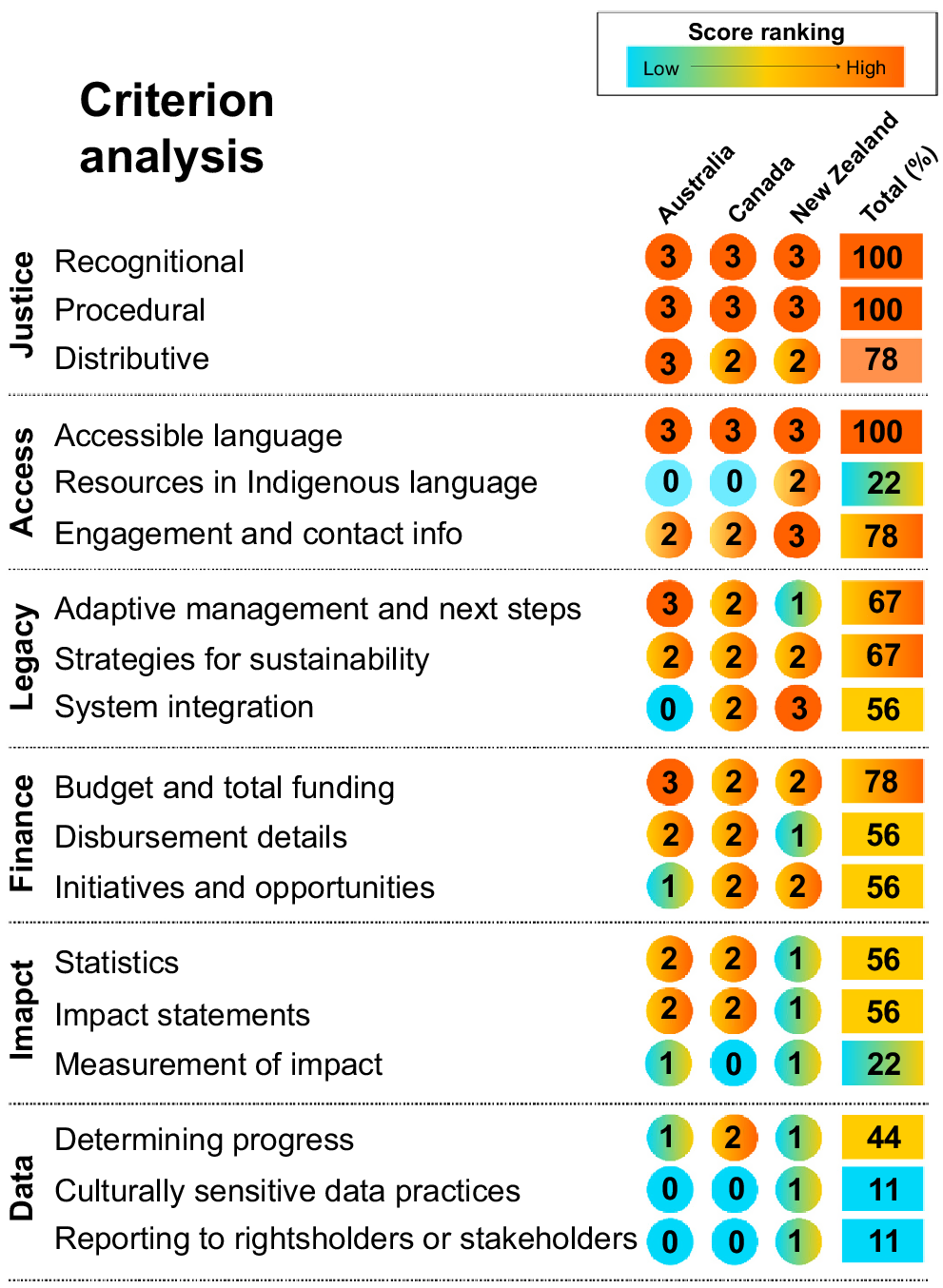

Analysis of how many programs from each country satisfied the fundamental, intermediate and advanced criteria within each BPS assessment category identified specific strengths and areas in need of improvement (Fig. 4). For justice, all programs encompassed elements of recognitional and procedural justice, with distributive justice being a component in most programs (seven of nine). For access, every program incorporated the use of accessible language, whereas seven of nine programs included explicit engagement instructions or contact information for stakeholders. Assessment of legacy criteria showed that six programs included elements of adaptive management and strategies aimed at ensuring the program sustainability and continuity beyond the initial implementation phase. Integration of program activities into existing systems and structures for long-term impact was identified in five programs. When it came to financial aspects, budgetary information was available for seven programs, whereas details on disbursements and financial initiatives and opportunities were featured in five of the programs. Finally, impact criteria, which included disaggregated statistics and general impact statements, were integrated into five of the programs.

Results of the Blue Peacebuilding Scorecard (Fig. 1) analysis of the presence of fundamental, intermediate and advanced criteria within each BPS assessment category performed on three state-led Indigenous-focused marine management programs in Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Categories are organised from top to bottom, ordered from highest to lowest performance. The number of programs fulfilling each criterion are presented for Australia, Canada and New Zealand, followed by the percentage representation for each criterion across programs, of the maximum possible total of nine (Column 6).

Criteria that scored less than 50% of the total achievable score may be in need of further development. Only four of nine programs integrated data collection and analysis for assessing progress and outcomes. New Zealand’s ‘Te Ohu Kaimoana (Māori Fisheries Trust)’ program was the only program that reported utilisation of culturally appropriate data collection methods and tools, accompanied by transparent and accountable reporting of results to Indigenous communities and stakeholders. Within the impact category, the measurement of program impact on social, economic and cultural well-being was present in only two programs, with examples found in Australia and New Zealand. In terms of accessibility, only two programs offered resources in Indigenous language(s), with all instances originating from New Zealand. The finance, legacy and justice categories did not exhibit criterion scores of <50%.

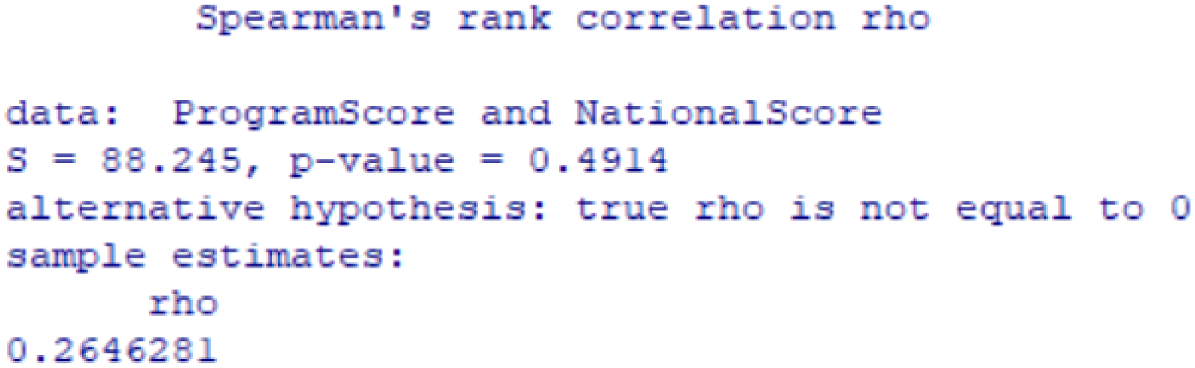

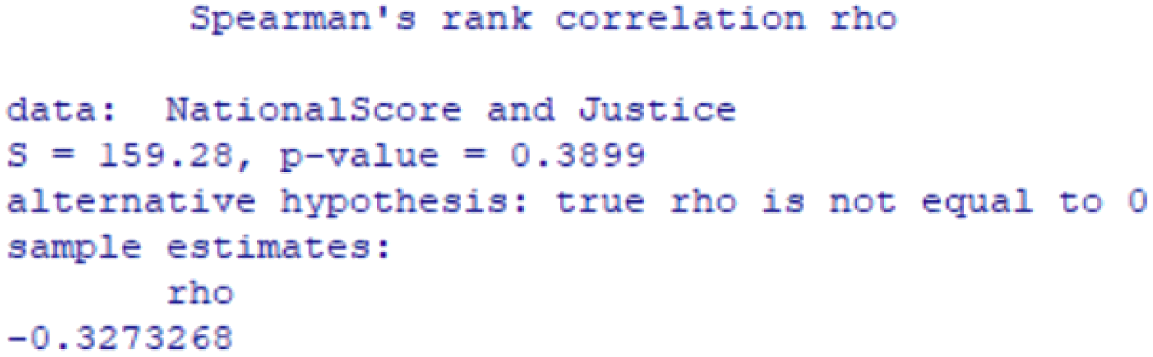

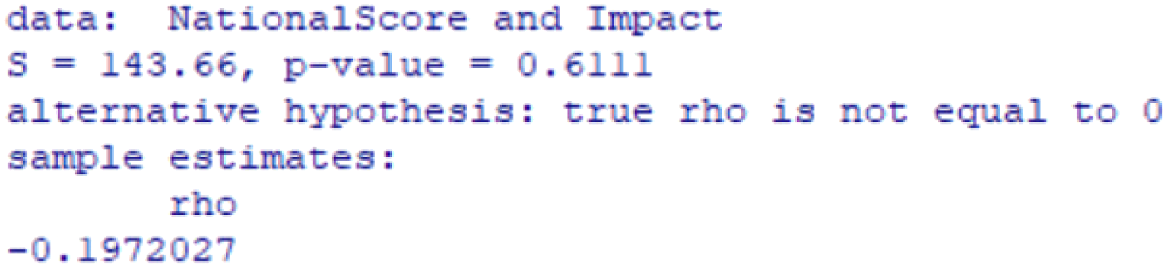

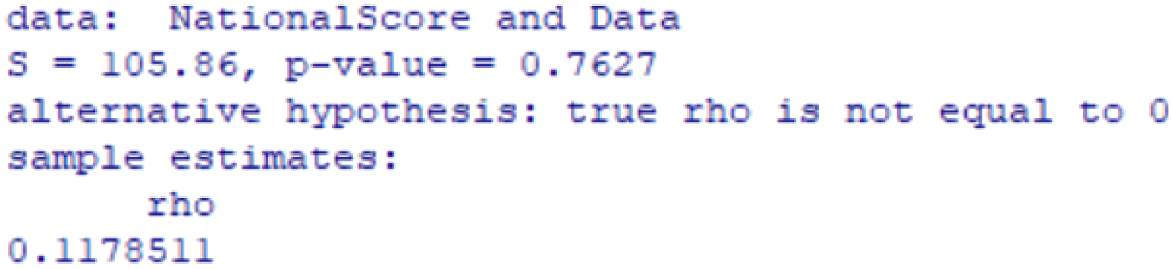

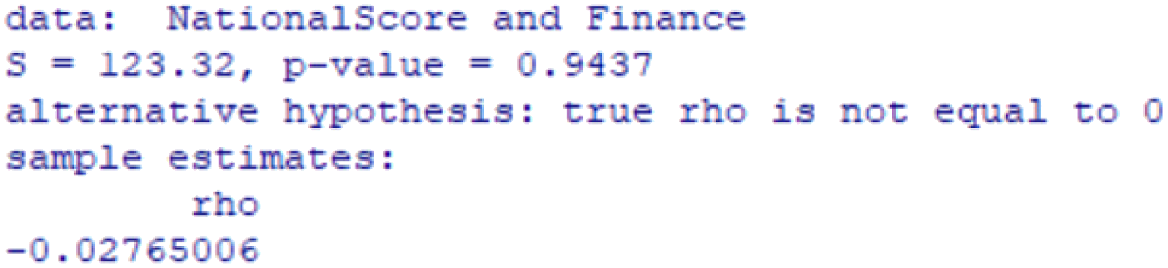

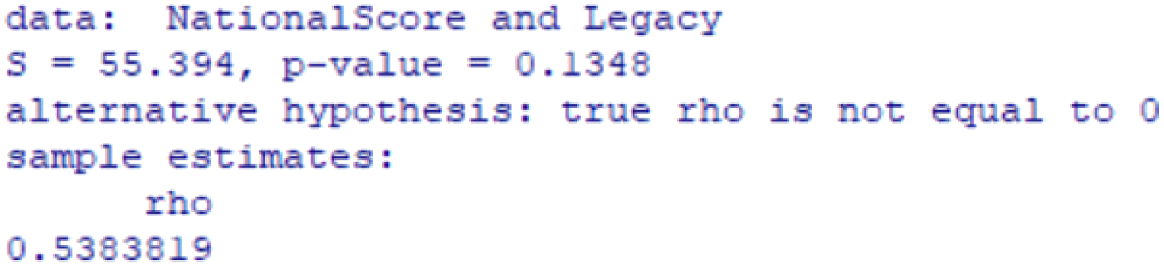

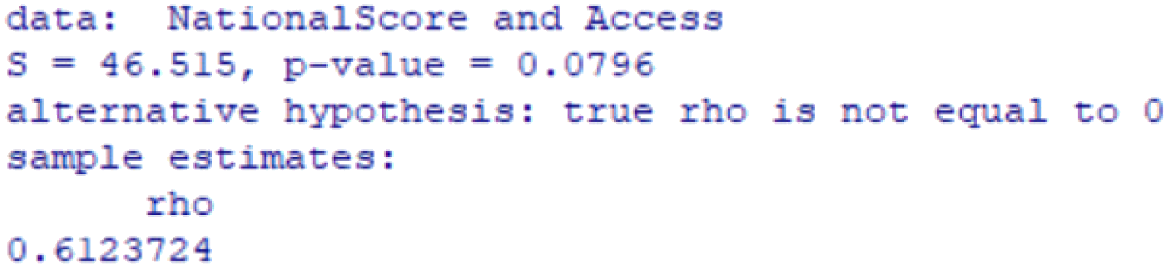

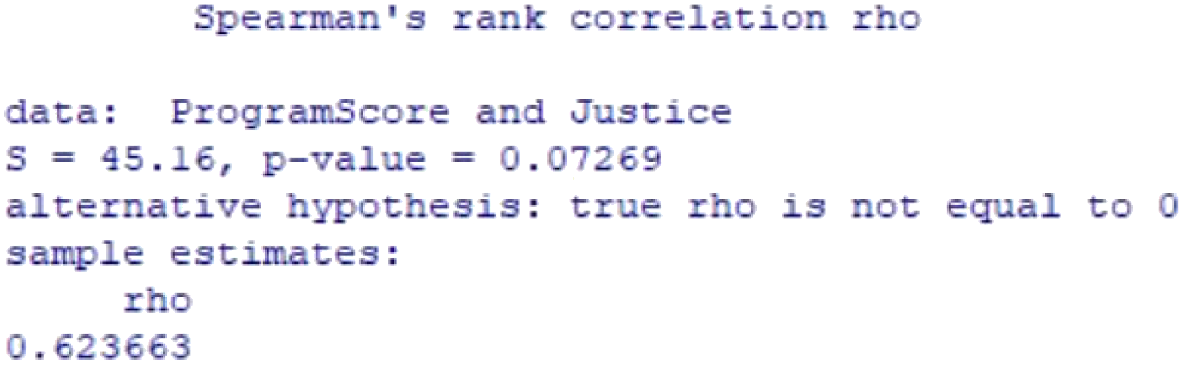

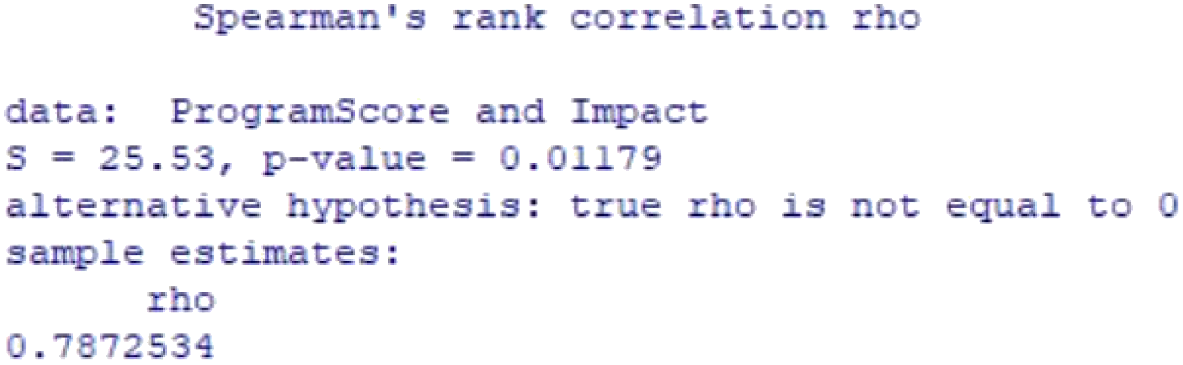

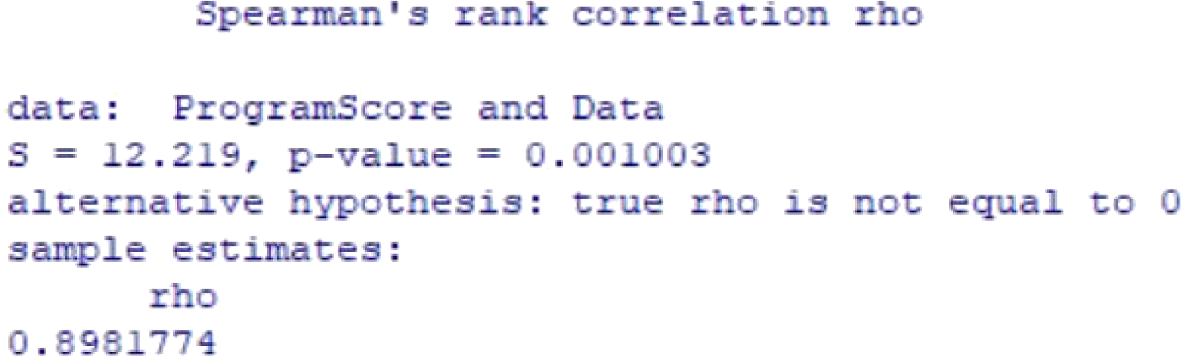

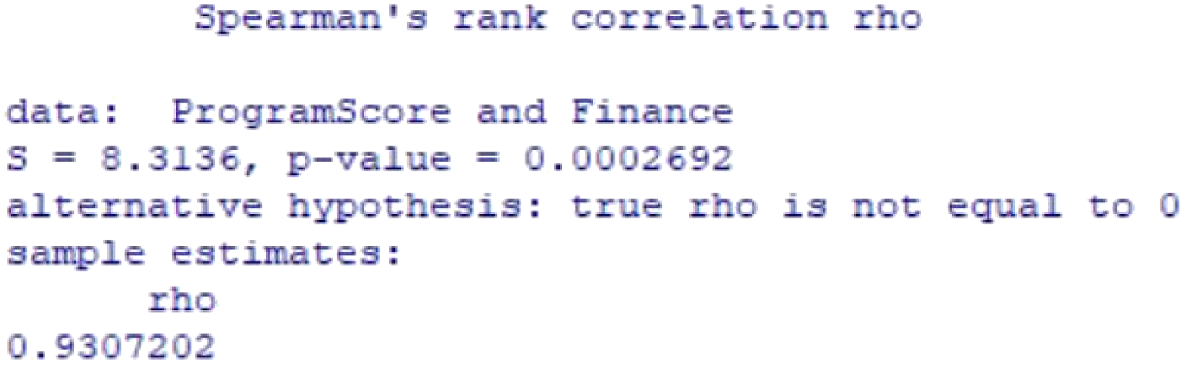

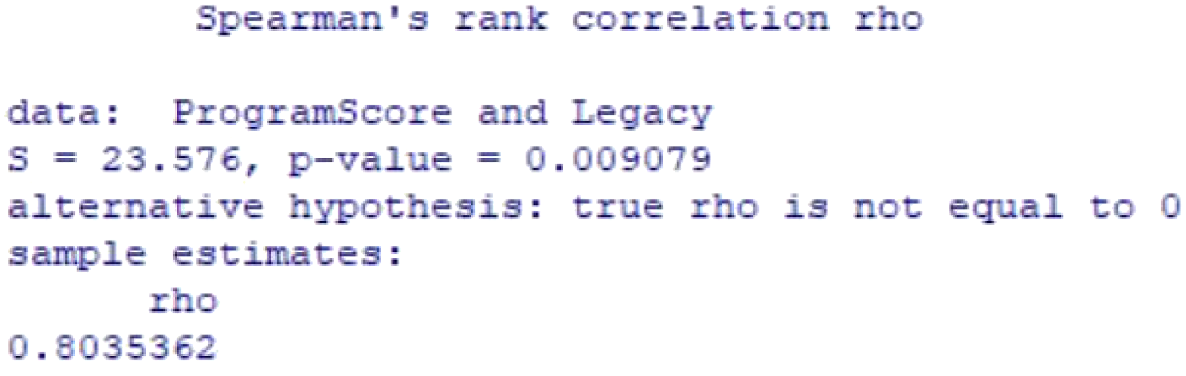

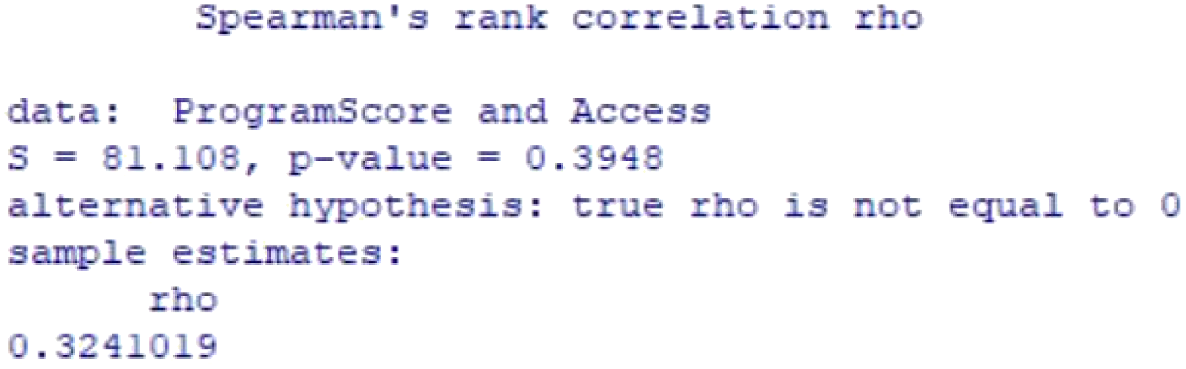

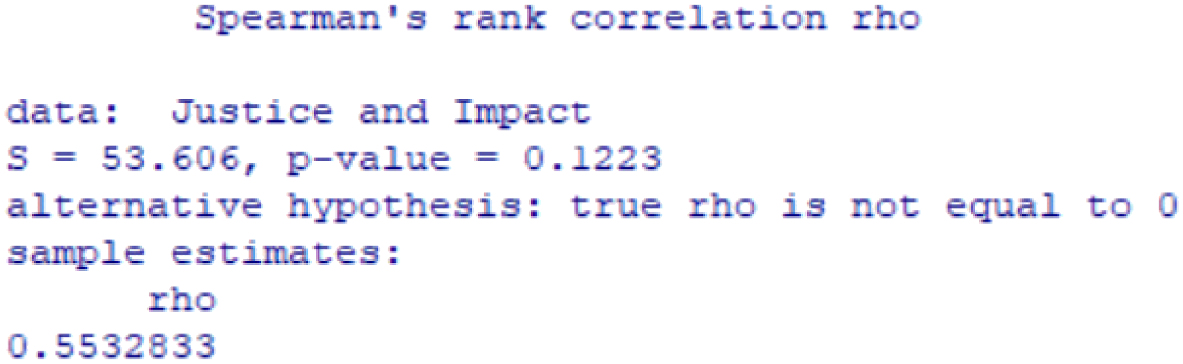

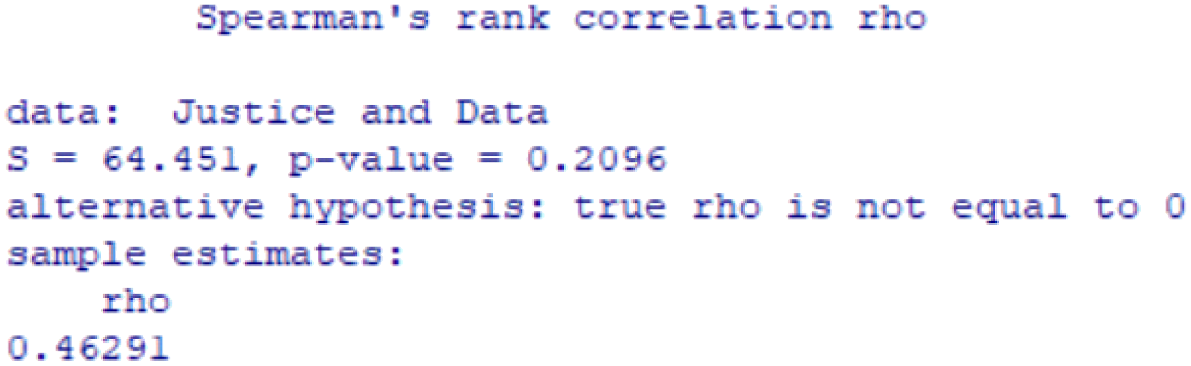

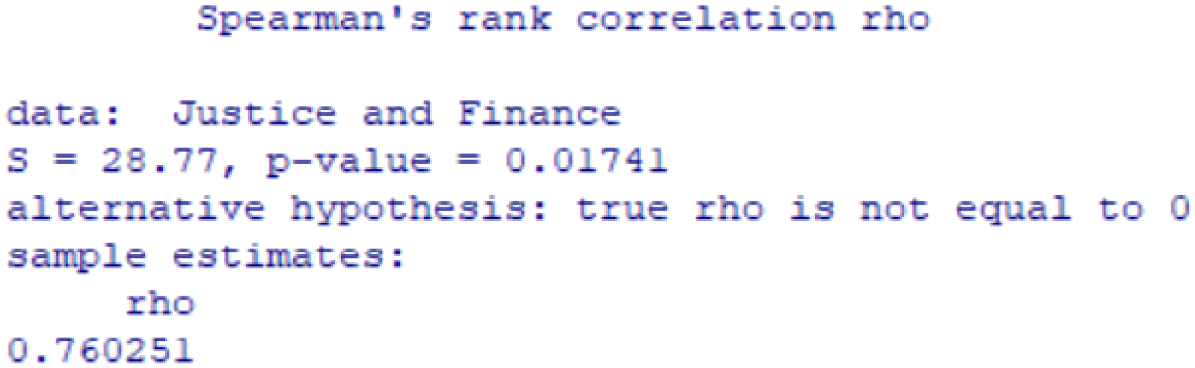

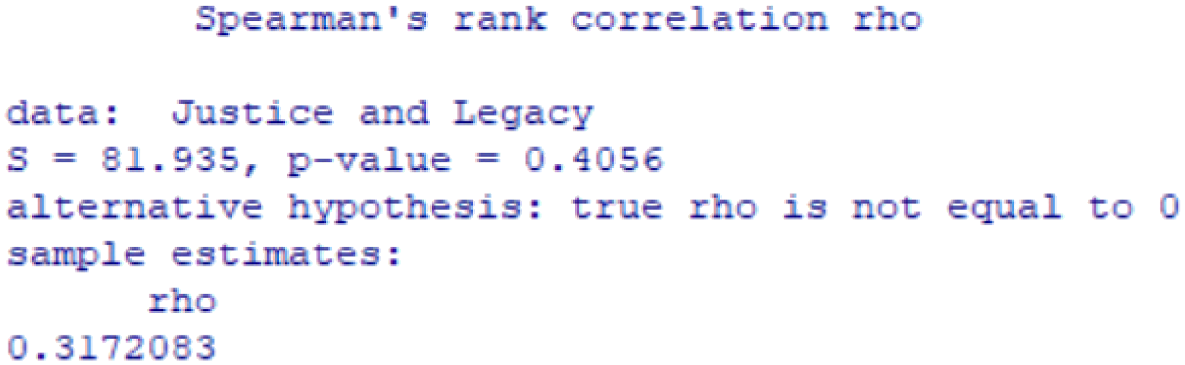

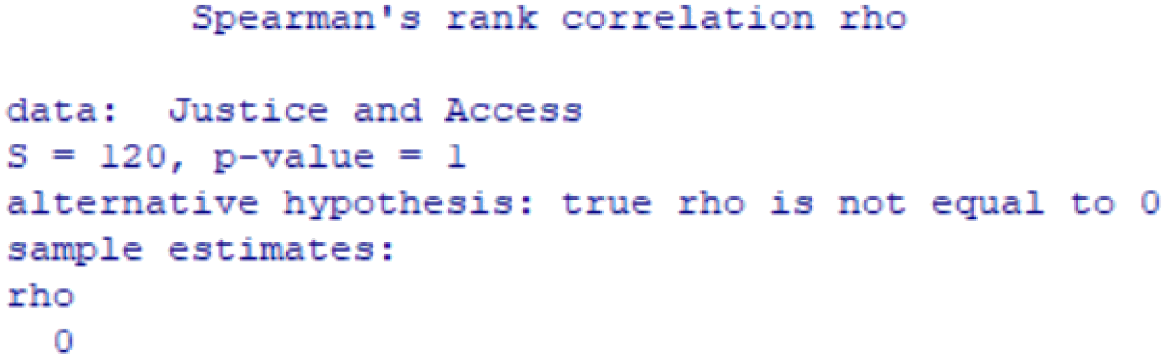

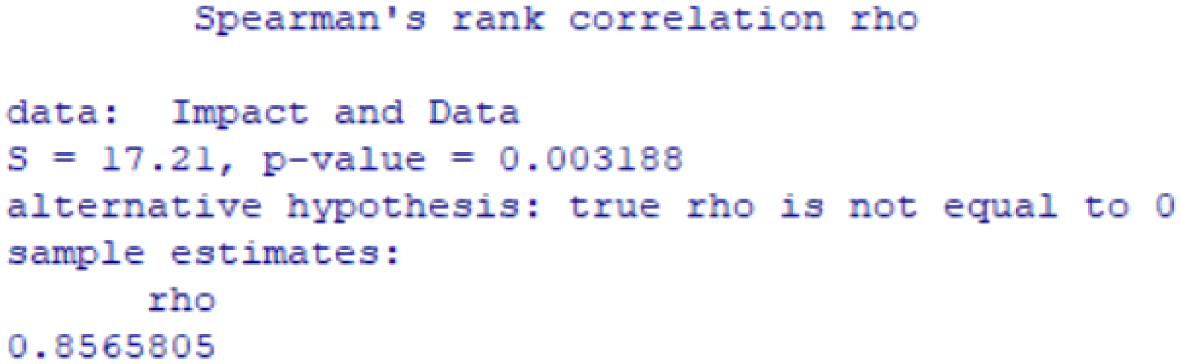

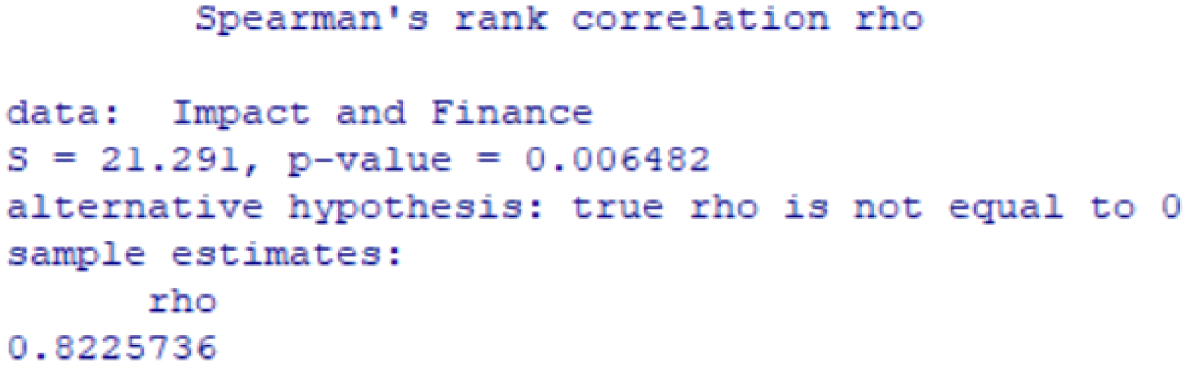

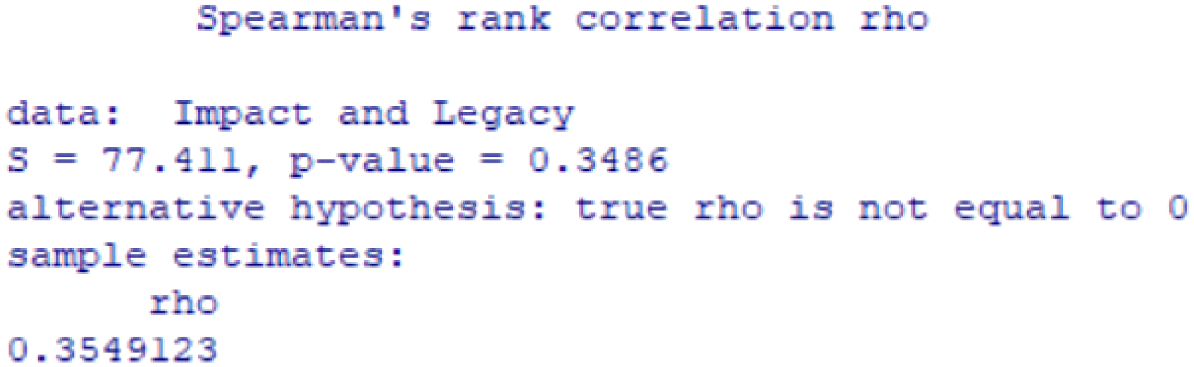

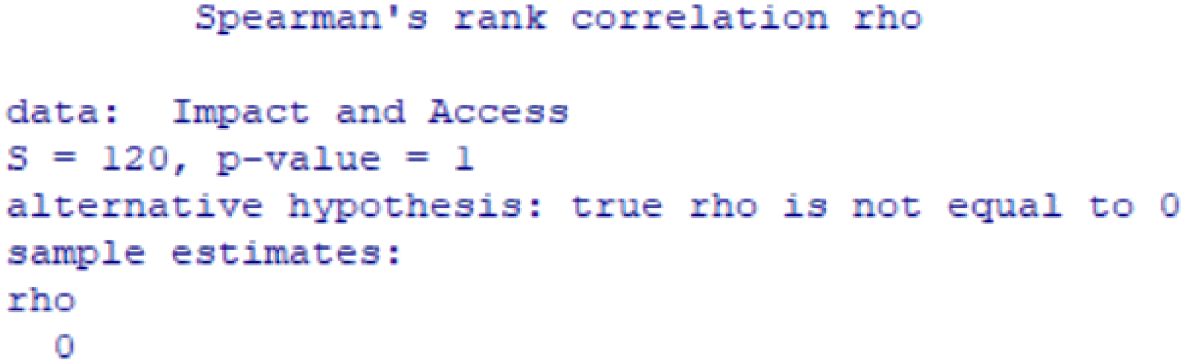

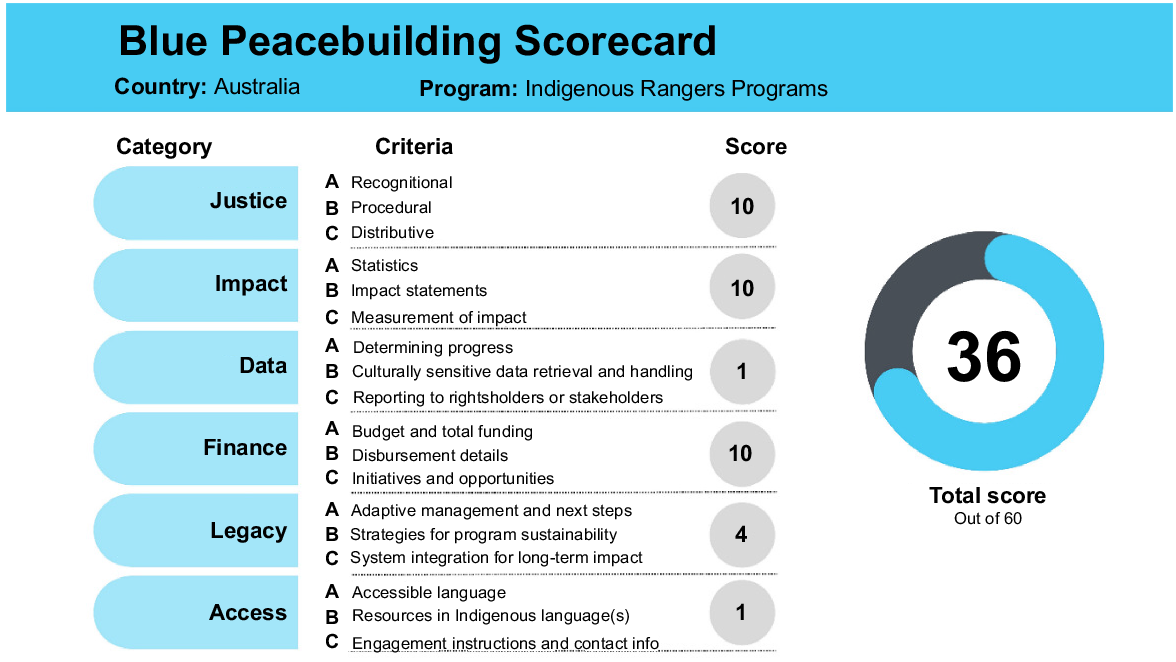

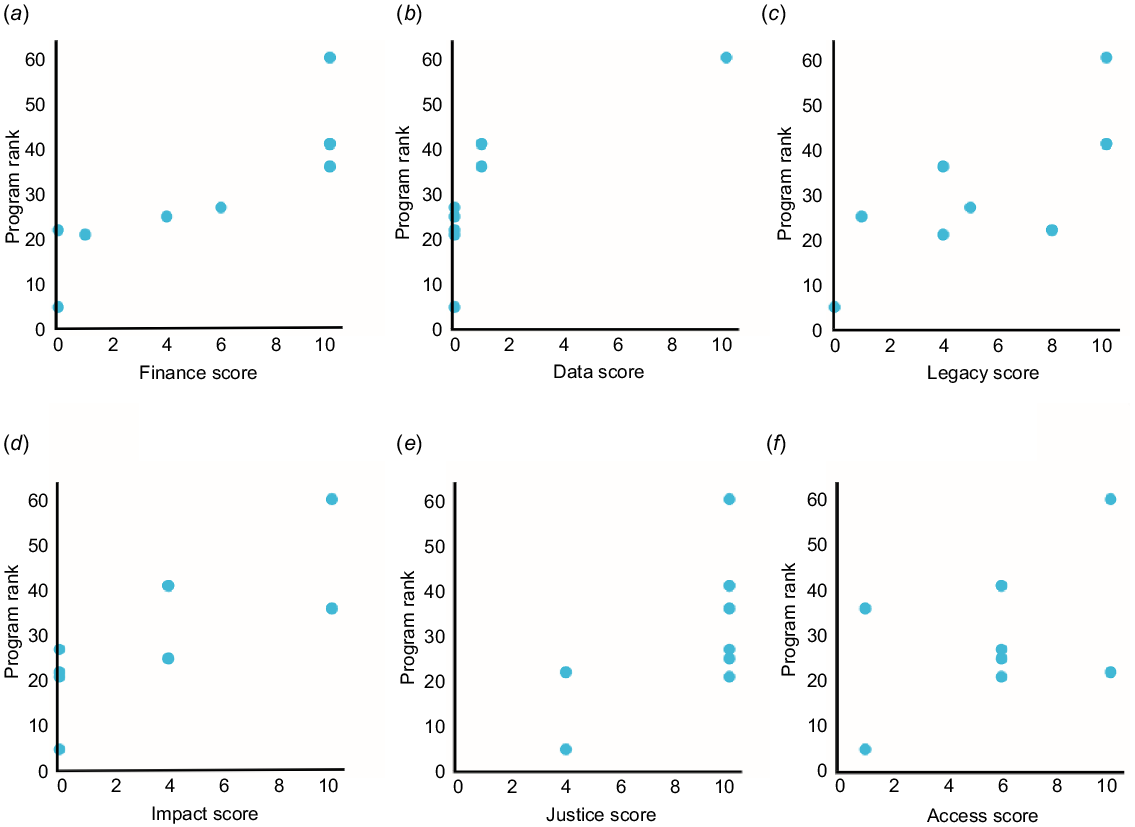

Pairwise Spearman rank correlations were calculated to evaluate the relationships between different aspects of BPS score rankings across all programs (n = 9), aiming to gauge the strength and direction of associations. No discernible relationship emerged between the rankings of program scores and aggregate national scores (Appendix 2). Analysis of the correlations between national rank scores and category rank scores showed no significant connections (Appendix 3). Pairwise Spearman rank correlations were also evaluated between the rankings of program and category scores to identify which categories may have been implicit within program design (Appendix 4). Positive correlations between program rank and category rank were identified for four of the six categories (see Fig. 5). The finance category exhibited a significant (monotonic) correlation with program scores (ρ = 0.9307, P = 0.0003) (see Fig. 5a), so too did the data category (ρ = 0.8982, P = 0.0010) (see Fig. 5b), the legacy category (ρ = 0.8035, P = 0.0091) (see Fig. 5c), and the impact category (ρ = 0.7873, P = 0.0118) (see Fig. 5d). By contrast, no significant correlation was found between ranked program scores and ranked justice category scores (ρ = 0.6237, P = 0.0727) (see Fig. 5e) or between ranked program scores and ranked access scores (ρ = 0.3241, P = 0.3948) (see Fig. 5f). These results suggest that program design may have prioritised all categories except for justice and access.

Spearman’s rank correlation test results illustrating the relationship between the ranking of state-led Indigenous marine development programs across Australia, Canada and New Zealand (n = 9) and rankings of the six evaluation categories: (a) finance, (b) data, (c) legacy, (d) impact, (e) justice and (f) access.

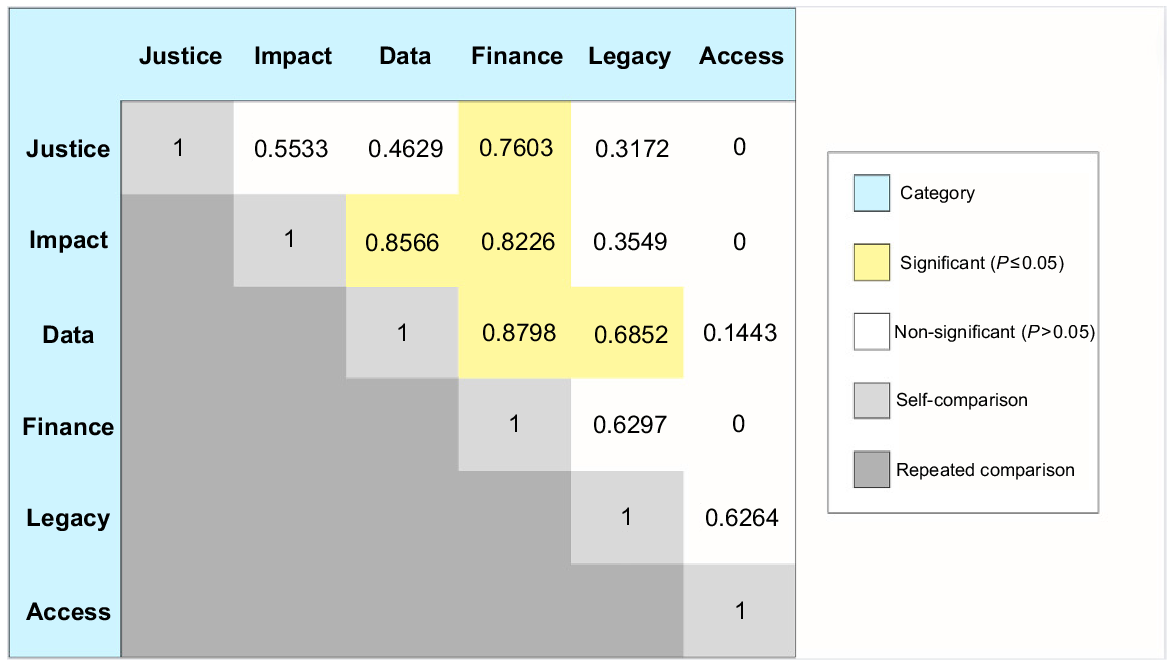

A comparison of the spearman’s rank correlation coefficients across categories showed significant positive correlations for 5 of the 15 comparisons (Fig. 6; Appendix 5). Data and finance demonstrated the strongest correlation with each other (0.8798), followed by impact and data (0.8566), impact and finance (0.8226), finance and justice (0.7603), and legacy and data (0.6852). The remaining categorical interactions were independent, which suggests that unequal effort may have been expended to incorporate elements from each of the categories within program design.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient values across the six program evaluation categories (Appendix 5) incorporated in the Blue Peacebuilding Scorecard (BPS). Blue cells denote categories, yellow indicates significant correlation values, white indicates non-significant values, light grey indicates intracategory correlation values and dark grey denotes repeated comparisons.

Discussion

Recognition of social equity and inclusion of Indigenous perspectives in governance are gaining momentum in Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Although initially resistant to adopting UNDRIP, these nations have since committed to its implementation (Commonwealth of Australia 2020; Government of Canada 2023b; Ministry for the Environment 2023). Progress has been observed through various state-led programs aimed at Indigenous marine governance. However, disparities persist in Indigenous participation levels and documentation of perceived community benefits across these initiatives. The variability in program scores highlights that Indigenous marine development programs do not uniformly deliver equitable outcomes or improved states of equity and justice. Moreover, program volume in this instance does not necessarily indicate that the needs and expectations of the Indigenous community are met across all areas of coastal and ocean management. For example, New Zealand’s ‘Te Ohu Kaimoana’ excels in protecting and advancing Māori fishing rights, whereas Canada’s ‘Marine Spatial Planning’ initiative, with its broad multi-sectoral approach, faces complexities in achieving equity goals. Addressing these challenges requires deeper scrutiny of governance frameworks and program impacts, emphasising the importance of robust impact assessment methodologies and culturally responsive data practices (Kukutai and Taylor 2016; Carroll et al. 2020).

Evaluation frameworks employed in diverse fields and geographical areas offer insights into best practices for Indigenous-focused marine management programs. For example, in the realm of health in the United States, Lawrence and James (2019) crafted the Indigenous Evaluation Framework to assess a federally sponsored initiative addressing chronic disease prevention in Indian Country. This framework underscores Indigenous core values and knowledge, addressing a historical backdrop of mistrust between tribal communities and the federal government concerning evaluation and data-driven practices (Lawrence and James 2019). Similarly, within the field of education, the Indigenous Evaluation Framework (IEF) places Indigenous wisdom at the forefront, emphasising the reclamation of power and challenging the notion that the Western evaluation framework is the sole valuable framework (Velez et al. 2022). Indigenous evaluation, as described by Waapalaneexkweew (2018), is rooted in the role of being caretakers of knowledge, community, or family, as well as in relational interactions and responsibilities to all elements of nature, the spirit world and each other. In both instances, the centrality of Indigenous knowledge and values underscores the crucial need to evaluate such programs in a manner that is culturally responsive, meaningful and holistic. Such frameworks can enhance program design and outcomes within the marine space, ensuring equity and justice for Indigenous communities. This further affirms the need to co-adapt the BPS framework, where Indigenous partners can guide the evaluation process and assign community-determined category weights.

We recognise that state-affirmed marine development programs represent only a fraction of diverse, culturally rich traditional ocean and coastal management programs and practices operating globally. Our findings, derived from analysing public-facing documentation provided by organisations leading state-supported programs, may not have universal applicability. Although the three studied nations demonstrate a varied set of approaches to Indigenous marine management, the findings may not translate to other regions or nations with different cultural, geographic, or governance contexts. Equity-related data transparency is a challenge that has been identified at the national policy level within other fields (Sapat et al. 2022). This issue may be hindering the ability to determine equity priorities within program design and thus limit the interpretation of the results. Organisations may be confronted with reporting challenges, given the scale and diversity of communities engaged. Non-state-led programs may offer better examples of equity and could be included in future analyses. Complementing existing programs with community-based participatory research, an equitable research approach that fosters collaboration between partners at all stages, may help improve impact evaluation and circumvent such challenges (Fawcett et al. 2003; Community Tool Box 2023). Establishing evaluative frameworks, such as the Indigenous Environmental Framework (IEF) (Lawrence and James 2019), reflects the qualities of diverse cultural and community landscapes. The IEF adheres to culturally sensitive protocols and equally incorporates data at the community, regional, and national levels. Such frameworks may aid in improving equitable design and outcomes within the marine space.

Identifying the strengths of reviewed programs can guide other nations in enhancing Indigenous marine rights and fulfilling UNDRIP commitments. Australia, for instance, demonstrates leadership in embedding justice criteria within development programs. Internationally, resource management initiatives often emphasise the value of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) rather than recognising and including Indigenous worldviews (Cisneros-Montemayor and Ota 2019). Although acknowledging TEK is a positive step, it may limit the incorporation of justice into marine governance. Australian programs consistently demonstrate procedural and distributive justice through initiatives such as the Indigenous Rangers Programs, which support skill building and equitable benefit sharing among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples by grant funding and skill-building initiatives (National Indigenous Australians Agency 2023). Canadian marine development programs were identified through the national Oceans Agenda (Fisheries and Oceans Canada 2023), which explicitly incorporates an ‘ocean governance and reconciliation’ component. Reconciliation is a process that holds transformative potential by fostering positive, reciprocal relationships essential for systemic decolonisation. Other nations have embraced reconciliation efforts and exemplified this approach, such as Australia’s ‘Reset the Relationship’ strategy in Tasmania, which prioritises cultural over political considerations and emphasises relationships over agreements (Lee 2019). Following Canada’s example of applying reconciliation efforts in ocean planning should be taken up by other ocean nations to account for and prioritise Indigenous marine rights and interests. This can support cultural preservation, sustainable resource management and environmental stewardship, enhancing climate change resilience and promoting education and awareness through collaboration and conflict resolution. National adoption of marine reconciliation priorities can thus lay a solid groundwork for advancing Indigenous marine rights and decolonising marine spaces in Canada and within other nations with settler-colonial dynamics.

Identifying program weaknesses offers guidance for future initiatives and contributes to improving blue justice in the reviewed nations and beyond. Persistent colonial structures within legal, political and economic contexts significantly affect Indigenous nations’ lived experiences (Clogg 2020). Despite ongoing disruptions to human–environment relationships caused by enduring settler-colonial structures (Whyte 2018), current Indigenous affairs discourse often confines colonialism to a historical context (Black 2021). An example of this in the marine context is the Australian doctrine of mare nullius, which denies Indigenous sovereignty, property and governance rights, leading to the fragmentation of coastal and marine territories for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (Mulrennan and Scott 2000). Addressing these discourses and structures in the marine space necessitates acknowledging the colonial past and present and adopting co-development procedures for ocean planning that are rooted in equity and justice to honour Indigenous rights and forge united futures.

Improving the inclusion of Indigenous languages in ocean governance resources is one possible avenue for improving equity and access for Indigenous coastal communities. Language serves as a relational tool connecting people to their country, as articulated by Callum Clayton-Dixon of the Anaiwan Language Revival Program:

For indigenous peoples, language is not simply a tool for communication; language is a medium for relating with kin and country in a healthy and proper way. Colonization has dislocated people from country, and the same has happened to our language. Decolonization is therefore the undoing of this destructive process. Our language was written down on pages now gathering dust in library and university archives. The people speaking our language were written out of history, along with much of the cultural context and connection to country inherent in Aboriginal languages. In putting community, country, and culture back into the language, we are determined to breathe new life into our ancient tongue, and this is just the beginning of a long journey ahead [Wright 2024].

Given the rich histories and ties of Indigenous Peoples to coastal and oceanic spaces in each of the case-study nations, this perspective should extend to the marine environment. The revitalisation of Indigenous languages within marine governance should mirror New Zealand’s integration of Māori language resources. However, the diversity of Indigenous languages within each region adds complexity; New Zealand has one Indigenous language (Māori), Canada boasts more than 70, and Australia has more than 250. This diversity, coupled with the impact of assimilationist state policies contributing to language loss in North America and Australia, underscores the multifaceted challenges faced (Wigglesworth and Keegan 2013; de Varennes and Kuzborska 2016; Statistics Canada 2023; The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies 2023). Ensuring the availability and appropriateness of Indigenous language resources, such as integrating local dialects into ocean literacy and education initiatives, acknowledges the intricate relationship among language, culture and planning. This reinforces the integral role of Indigenous perspectives in advancing justice for Indigenous Peoples across various sectors, and highlights the importance of culturally appropriate communication strategies that align with community needs and language realities.

Most programs demonstrated advanced levels of justice, indicating a strong emphasis on this aspect in program design across national initiatives. Legacy, access and finance criteria also received considerable attention, although somewhat inconsistently. Central development priorities for each case-study nation should focus on enhancing the inclusion of data and impact criteria, because these categories showed the lowest overall representation. Data collection plays a pivotal role in enhancing Indigenous engagement in government programs that directly influence Indigenous outcomes and in improving state accountability (Calma 2006). Culturally responsive data practices must be a top priority to ensure ethical program management and support Indigenous rights and interests concerning data related to Indigenous societies, lands and ways of life, an approach known as Indigenous data sovereignty (Kukutai and Taylor 2016; Snipp 2016; Rainie et al. 2017; Carroll et al. 2019, 2020). Practical steps include adopting the FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship, along with the complementary CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance (Carroll et al. 2020). Together, these principles promote equitable data practices. Further to this, rigorous impact measurement methodologies that are both cost-effective and feasible in local contexts must be prioritised to enhance the effectiveness of development efforts. This entails incorporating social impact assessments through the collection and analysis of relevant data and indicators to assess progress and outcomes. Transparent and accountable reporting of program results to Indigenous communities and stakeholders is also crucial for fostering trust and affirming the legitimacy of development initiatives.

The ongoing development of state-led programs can draw inspiration from exemplary Indigenous saltwater initiatives worldwide that embed equity and justice into their programs. One such notable initiative is the United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Equator Prize (EP), which annually recognises 10 exceptional Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities globally for their grassroots initiatives and application of traditional knowledge. These initiatives demonstrate inventive, nature-based strategies that achieve community development objectives, enhance community resilience, and address challenges spanning economic, environmental, political and public health domains (United Nations Development Programme 2023a). In contrast to the BPS approach, which focuses on state-led efforts, the EP is awarded to non-governmental initiatives based on criteria including impact, innovation, scalability or replicability, resilience, adaptability, self-sufficiency, reduced inequalities, social inclusion and gender equality (United Nations Development Programme 2023b). However, both the BPS and EP share overlapping criteria, emphasising measurable impact across social, economic and environmental domains. The emphasis of the EP on reduced inequalities and enhanced self-sufficiency aligns closely with the justice category of the BPS, highlighting Indigenous justice as a central priority in both frameworks.

The study’s global context emphasised that despite initial opposition to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Australia, Canada and New Zealand have committed, through policy and programs, to its implementation. However, more research is needed to understand the lived experience of Indigenous participants within these state-led programs to shed light on perceived justice and the equity of program outcomes, as evidenced through lived experience. Future research should concentrate on engaging participants and conducting qualitative analyses to establish Indigenous-led weightings for the distinct categories within the BPS, namely, justice, impact, data, finance, legacy and access. Moreover, specific criterion recommendations, such as the identification of desired Indigenous language resources, can be further improved. This approach aims to effectively address and bridge equity gaps identified by program participants.

Longitudinal studies may provide invaluable insights into the evolution of program performance over time, allowing for a nuanced understanding of their effectiveness. Conducting comparative analyses with Indigenous-focused marine management programs in other nations could offer essential benchmarks for improvement, fostering a collaborative approach to enhance marine governance practices on a global scale. At the same time, this raises the following critical question:

Is adapting another colonial structure the best way forward for Indigenous partner organisations, or do alternative, community-driven models better serve Indigenous self-determination?

Although adapting existing structures can provide immediate pathways for policy engagement, ensuring that these frameworks are reshaped by Indigenous priorities, governance models and knowledge systems set forth by Indigenous partner organisations is essential for meaningful and lasting equity.

The adaptability of the scorecard, supplemented by future research, holds promise for being a valuable tool for evaluating equity not only in Indigenous-based marine programs but also in diverse initiatives rooted in Indigenous perspectives. The case-study nations discussed in this paper are actively working toward embracing UNDRIP, marking an ongoing journey of reconciliation. Empowerment of coastal Indigenous communities lies in prioritising equity and justice through marine program development, continued research, and ongoing engagement to foster empowerment leading to equitable and just program outcomes.

Conclusions

This study has explored the integration of equity and justice within Indigenous marine development programs across Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, all being nations that are grappling with colonial legacies while actively pursuing equitable management tools that respect Indigenous rights and foster unified futures. As these nations evolve in their perspectives and priorities, evidenced by commitments to implementing UNDRIP and the emergence of Indigenous development programs, ongoing progress through program evaluation and reflection remains imperative amidst the dynamic discourse on Indigenous rights and policy shifts.

This research underscores the critical need to assess both the depth and breadth of social equity within program design and impact to better understand equity and justice outcomes delivered for Indigenous Peoples. Areas for further national development have been identified to inform program refinement and policymaking through the application of the BPS. The BPS is a marine reconciliation tool that can lead to cultural preservation, sustainable resource management, climate resilience, education and harmonious coexistence. It can initiate steps towards fostering peace within government-managed Indigenous ocean and coastal spaces, catalysing internal program reviews to enhance effectiveness and navigate political transitions. It is crucial to note that this approach to program evaluation does not substitute Indigenous partnerships, nor is it preferred to establishing co-management processes from the outset. Rather, it signifies a commitment to reconciliation when utilised with transparency, appropriateness and in collaboration with Indigenous nations. Such efforts hold promise in mitigating stakeholder fatigue and conflicts by acknowledging program deficiencies and demonstrating readiness for cooperation.

The authors advocate for a collaborative review of the BPS involving Indigenous and non-Indigenous partners, focusing on refining relevant categories, determining their weightings, establishing desired outcomes and setting benchmarks for monitoring progress. This inclusive approach ensures that community needs are accurately reflected in policies and programs designed to affect them. Furthermore, integrating qualitative records, such as storytelling, artworks, songs and dances, can provide additional context and deepen understanding of program impacts. The governance of such records should be determined collaboratively to uphold data sovereignty, ensuring equitable access and utilisation.

Future research should prioritise developing holistic and culturally responsive approaches to program evaluation in the marine space through ongoing community engagement, responsive to lived experiences and evolving needs. Empowering coastal Indigenous communities demands sustained efforts to amplify their voices and shape program outcomes rooted in equity and justice. These recommendations set a strategic path for development, with implementation efforts marking tangible progress towards realising an equity-first, justice-centred Blue Economy. Collectively, these actions will contribute towards reconciling the past, serving the present, and shaping the future.

Positionality statement

Jillian Conrad

I acknowledge that my background, lived experiences and social positioning shape my perspectives, research approach and interactions with communities. This statement reflects on my identity, biases and commitments as I engage in Sea Country planning research. I am a White, Canadian-born settler and a woman of German and British descent. My position as a non-Indigenous, middle-class researcher has afforded me unearned privilege, shaping how I engage with equitable ocean governance. I have lived on unceded Indigenous territories throughout my life, growing up in Mi’kma’ki (the Traditional Lands of the Mi’kmaq in Eastern Canada), studying in Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee territory, and now residing on the lands of the Yagambah language peoples in Australia. These experiences influence my research, decision-making and collaborations. I recognise the extensive historical and ongoing traumas of colonisation in ocean governance and the institutions I have studied and worked within. My research on Sea Country planning in Australia acknowledges the histories of colonialism, power imbalances and systemic inequities that continue to shape ocean and coastal governance. I strive to engage ethically, reciprocally and with cultural integrity in my work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia. I am committed to challenging injustice and advocating for equitable governance structures. My work is informed by continuous learning from Indigenous perspectives, shared through relationships, literature, stories, and art. I remain mindful of power dynamics, centring Indigenous knowledge, lived experiences and self-determination in my research. I commit to transparency by clearly articulating my role, intentions, and limitations. I prioritise reciprocity by ensuring my work benefits communities and contributes to shifting the burden of responsibility onto non-Indigenous decision-makers. Recognising positionality as dynamic, I remain open to learning, unlearning and adapting, striving to contribute ethically, respectfully and inclusively to this field.

The authorship team as a whole brings diverse perspectives and lived experiences to equity research and Indigenous-supporting work. As part of Griffith University, we have the pleasure of working on the lands of the Yugarabul, Yuggera, Jagera, Turrbal and Kombumerri Peoples. We acknowledge and appreciate the Traditional Custodians of these landsand pay our deepest respect to Elders, past, present and emerging, while also extending respect to all other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

Declaration of use of AI

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT (ver. GPT-4o) for the purpose of editing and improving readability. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of interest

Christopher Frid and Mibu Fischer are guest editors of this collection, but were not involved in the peer review or decision-making process for this paper. Marine and Freshwater Research encourages its editors to publish in the journal and they are kept totally separate from the decision-making processes for their manuscripts. The authors have no further conflicts of interest to declare.

Declaration of funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Blue Economy Cooperative Research Centre, established and supported under the Australian Government’s Cooperative Research Centres Program, grant number CRC-20180101. This research did not receive any other specific funding.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Blue Economy Cooperative Research Centre, established and supported under the Australian Government’s Cooperative Research Centres Program. The authors extend their sincere appreciation to Mibu Fischer, an Indigenous scholar, for her invaluable contribution as a reviewer, bringing unique perspectives and insights that enriched the scholarly discourse of this paper.

References

Armitage A (1995) ‘Comparing the Policy of Aboriginal Assimilation: Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.’ (UBC Press) Available at https://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Y-hBstoLN-MC

Australian Electoral Commission (2023) National results: Referendum. (AEC) Available at https://results.aec.gov.au/29581/Website/ReferendumNationalResults-29581.htm

Australian Human Rights Commission (2021) Implementing UNDRIP. (AHRC) Available at https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-10/implementing_undrip_-_australias_third_upr_2021.pdf

Ban NC, Frid A (2018) Indigenous peoples’ rights and marine protected areas. Marine Policy 87, 180-185.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bennett NJ, Cisneros-Montemayor AM, Blythe J, et al. (2019a) Towards a sustainable and equitable blue economy. Nature Sustainability 2(11), 991-993.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bennett NJ, Blythe J, Cisneros-Montemayor AM, Singh GG, Sumaila UR (2019b) Just transformations to sustainability. Sustainability 11(14), 3881.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bennett NJ, Blythe J, White CS, Campero C (2021) Blue growth and blue justice: ten risks and solutions for the ocean economy. Marine Policy 125, 104387.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Berke PR, Malecha ML, Yu S, Lee J, Masterson JH (2019) Plan integration for resilience scorecard: evaluating networks of plans in six US coastal cities. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 62(5), 901-920.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Black D (2021) Settler–colonial continuity and the ongoing suffering of Indigenous Australians. In ‘E-International Relations’. (University of the West of England: Bristol, UK) Available at https://www.e-ir.info/2021/04/25/settler-colonial-continuity-and-the-ongoing-suffering-of-indigenous-australians/

Calma T (2006) Social justice and human rights: using Indigenous socioeconomic data in policy development. In ‘Assessing the evidence on Indigenous socioeconomic outcomes’. (Ed. BH Hunter) CAEPR Monograph number 26, pp. 299–310. (ANU Press) Available at http://www.jstor.org.libraryproxy.griffith.edu.au/stable/j.ctt2jbj3f.31

Carroll SR, Rodriguez-Lonebear D, Martinez A (2019) Indigenous data governance: strategies from United States Native Nations. Data Science Journal 18(1), 31.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Carroll SR, Garba I, Figueroa-Rodríguez OL, et al. (2020) The CARE principles for Indigenous data governance. Data Science Journal 19, 43.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chai N (2009) ‘Sustainability performance evaluation system in government: a balanced scorecard approach towards sustainable development.’ (Springer) doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3012-2

Cisneros-Montemayor AM, Ota Y (2019) Coastal Indigenous peoples in global ocean governance. In ‘Predicting future oceans’. (Eds AM Cisneros-Montemayor, WWL Cheungpp, Y Ota) pp. 317–324. (Elsevier) doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-817945-1.00028-9

Cisneros-Montemayor AM, Moreno-Báez M, Voyer M, et al. (2019) Social equity and benefits as the nexus of a transformative Blue Economy: a sectoral review of implications. Marine Policy 109, 103702.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cisneros-Montemayor AM, Ducros AK, Bennett NJ, et al. (2022) Agreements and benefits in emerging ocean sectors: are we moving towards an equitable Blue Economy? Ocean & Coastal Management 220, 106097.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Clogg J (2020) Colonialism is alive and well in Canada. March 11, 2020. (West Coast Environmental Law Association: Vancouver, BC, Canada) Available at https://www.wcel.org/blog/colonialism-alive-and-well-canada

Closing the Gap (2020) National agreement on closing the gap. Available at https://www.closingthegap.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-09/ctg-national-agreement_apr-21-comm-infra-targets-updated-24-august-2022_0.pdf

Commonwealth of Australia (2020) National agreement on closing the gap. Available at https://www.closingthegap.gov.au/national-agreement

Community Tool Box (2023) Evaluating community programs and initiatives: participatory evaluation. Available at https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/evaluate/evaluation/participatory-evaluation/main

Conrad JE, Frid CLJ (in press) Blue peacebuilding: exploring social equity and Indigenous justice within SDG 14 and Blue Economy initiatives. In ‘Proceedings of the International Conference on Achieving Ocean Equity: Innovative, Fair, Inclusive, and Sustainable Strategies and Blue Impact Investments’, 27 February–1 March 2023, Wollongong, NSW, Australia. (Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, Japan)

Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (2021) Government of Canada and the duty to consult. Available at https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1331832510888/1609421255810

Cutter SL (1995) Race, class and environmental justice. Progress in Human Geography 19(1), 111-122.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

de Varennes F, Kuzborska E (2016) Language, rights and opportunities: the role of language in the inclusion and exclusion of Indigenous Peoples. International Journal on Minority and Group Rights 23(3), 281-305.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fawcett SB, Boothroyd R, Schultz JA, et al. (2003) Building capacity for participatory evaluation within community initiatives. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community 26, 21-36.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (2023) Canada’s oceans agenda. (Government of Canada–Gouvernement du Canada) Available at https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/campaign-campagne/oceans/index-eng.html

Government of Canada (2010) Canada endorses the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. (Government of Canada–Gouvernement du Canada) Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/news/archive/2010/11/canada-endorses-united-nations-declaration-rights-indigenous-peoples.html

Government of Canada (2021a) Backgrounder: United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act. (Government of Canada–Gouvernement du Canada) Available at https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/declaration/about-apropos.html#:~:text=This%20Act%20requires%20the%20Government,to%20achieve%20the%20Declaration’s%20objectives

Government of Canada (2021b) Principles respecting the Government of Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples. (Government of Canada–Gouvernement du Canada) Available at https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/principles-principes.html#:~:text=Indigenous%20peoples%20have%20a%20special,of%20the%20Constitution%20Act%2C%201982

Government of Canada (2023a) Treaties and agreements. (Government of Canada–Gouvernement du Canada) Available at https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100028574-/1529354437231

Government of Canada (2023b) Implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act. (Government of Canada–Gouvernement du Canada) Available at https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/declaration/index.html

Hiriart-Bertrand L, Silva JA, Gelcich S (2020) Challenges and opportunities of implementing the marine and coastal areas for Indigenous peoples policy in Chile. Ocean & Coastal Management 193, 105233.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Issifu I, Dahmouni I, Deffor EW, Sumaila UR (2023) Diversity, equity, and inclusion in the Blue Economy: why they matter and how do we achieve them? Frontiers in Political Science 4, 1067481.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Keleher H (2013) Policy scorecard for gender mainstreaming: gender equity in health policy. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 37(2), 111-117.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kerr S, Colton J, Johnson K, Wright G (2015) Rights and ownership in sea country: implications of marine renewable energy for indigenous and local communities. Marine Policy 52, 108-115.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kukutai T, Taylor J (Eds) (2016) Front matter. In ‘Indigenous data sovereignty. Vol. 38’. pp. i–iv. (ANU Press) Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1q1crgf.1

Lawrence TJ, James RD (2019) Good health and wellness: measuring impact through an indigenous lens. Preventing Chronic Disease 16, E108.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Le Heron E, Le Heron R, Taylor L, Lundquist CJ, Greenaway A (2020) Remaking ocean governance in Aotearoa New Zealand through boundary-crossing narratives about ecosystem-based management. Marine Policy 122, 104222.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lee E (2019) ‘Reset the relationship’: decolonising government to increase Indigenous benefit. Cultural Geographies 26(4), 415-434.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Liu KFR (2007) Evaluating environmental sustainability: an integration of multiple-criteria decision-making and fuzzy logic. Environmental Management 39, 721-736.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McGregor D, Whitaker S, Sritharan M (2020) Indigenous environmental justice and sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 43, 35-40.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mills J, McNicol S, Haughton J (2023) Constitution Alteration (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice) 2023. (Parliament of Australia) Available at https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/bd/bd2223a/23bd080

Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (2009) Statement on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: speech, Canberra. (Parliament of Australia) Available at https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id%3A%22media%2Fpressrel%2F418T6%22

Ministry for the Environment (2023) Mana Whakahono ā Rohe: Iwi participation arrangements. (Te Kāwanatanga o Aotearoa–New Zealand Government) Available at https://environment.govt.nz/acts-and-regulations/acts/resource-management-act-1991/mana-whakahono-a-rohe-iwi-participation-arrangements/

Mitchell FM, Billiot S, Lechuga-Pena S (2020) Utilizing photovoice to support Indigenous accounts of environmental change and injustice. Genealogy 4(2), 51.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mitrou F, Cooke M, Lawrence D, Povah D, Mobilia E, Guimond E, Zubrick SR (2014) Gaps in Indigenous disadvantage not closing: a census cohort study of social determinants of health in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand from 1981–2006. BMC Public Health 14(1), 201.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mulrennan M, Scott C (2000) Mare Nullius: Indigenous rights in saltwater environments. Development and Change 31(3), 681-708.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

National Indigenous Australians Agency (2023) Environment. (NIAA) Available at https://www.niaa.gov.au/indigenous-affairs/environment

New Zealand Parliament (2010) Ministerial Statements – UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples – Government Support. (New Zealand Parliament–Pāremata Aotearoa) Available at https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/hansard-debates/rhr/document/49HansD_20100420_00000071/

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020) Chapter 1: Overview of Indigenous governance in Canada: evolving relations and key issues and debates. In ‘Linking Indigenous Communities with Regional Development in Canada’. OECD Rural Policy Reviews, pp. 37–66. (OECDiLibrary) doi:10.1787/fa0f60c6-en

Parsons M, Fisher K (2022) Decolonising flooding and risk management: Indigenous Peoples, settler colonialism, and memories of environmental injustices. Sustainability 14(18), 11127.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Parsons M, Taylor L, Crease R (2021) Indigenous Environmental justice within marine ecosystems: a systematic review of the literature on Indigenous peoples’ involvement in marine governance and management. Sustainability 13(8), 4217.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Proctor W, Drechsler M (2006) Deliberative multicriteria evaluation. Environment and Planning – C. Government and Policy 24(2), 169-190.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Rainie SC, Schultz JL, Briggs E, Riggs P, Palmanteer-Holder NL (2017) Data as a strategic resource: self-determination, governance, and the data challenge for indigenous nations in the United States. The International Indigenous Policy Journal 8(2), 1-29.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |