Barriers and enablers to referral of older adults to hearing care: a cross-sectional questionnaire study of Australian general practitioners

Ella C. Davine A * , Peter A. Busby A , Sanne Peters B , Jill J. Francis B C , David Harris D , Barbra H. B. Timmer E F Julia Z. Sarant A

A * , Peter A. Busby A , Sanne Peters B , Jill J. Francis B C , David Harris D , Barbra H. B. Timmer E F Julia Z. Sarant A

A

B

C

D

E

F

Abstract

Acquired hearing loss has significant negative effects on quality of life, general health, maintenance of independence, and healthy aging. Despite this, rates of self-directed help seeking are low, as are referral rates from general practice to hearing care. This study aimed to explore the barriers and enablers to general practitioner (GP) referral of adults aged 50+ years to hearing care.

A cross-sectional questionnaire was designed using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change and administered to a self-selected sample of 103 Australian GPs.

Identified enablers included positive beliefs about the consequences of hearing rehabilitation and experiencing positive role models of hearing care including referral. Contextual issues such as time constraints, costs of hearing care, and limited availability of local audiology resources were the most frequently cited barriers to referral. Content analysis of free-format responses yielded 25 themes in total, eight of which were not previously documented in the published literature.

GP beliefs about hearing care and the outcomes of referral were generally positive, however, logistical concerns and contextual constraints such as restricted appointment times were prominent barriers to hearing care referral. Identifying the key barriers and enablers to GP referral of older adults to hearing care will facilitate the design of targeted behavioural interventions aimed at increasing referral rates. Further qualitative investigation of the key modifiable barriers and enablers identified in this study is warranted to clarify how best to address these in clinical practice.

Keywords: audiology, barriers, COM-B model, enablers, general practice, health, healthy aging, hearing care, older adults, primary care, referral, Theoretical Domains Framework.

Introduction

Acquired hearing loss is associated with significant impacts on mental, physical, and social well-being (Genther et al. 2014; Livingston et al. 2017; Vancampfort et al. 2017). Despite the proven efficacy of hearing interventions such as hearing aids, hearing loss remains under diagnosed and under treated in adults aged 50 years and over, due in part to low levels of help seeking from those affected (Wilson et al. 2017; Bisgaard et al. 2022). Nearly one in three adults who have noticed a hearing difficulty have never consulted a clinician regarding their hearing, and 28% have never had any form of hearing test (Mahboubi et al. 2018). Among adults who meet the audiological criteria for the provision of hearing aids, the average reported delay between meeting these criteria and receiving a hearing aid is 8.9 years; with 33.4% of older adults with a moderate hearing loss not owning a hearing aid (Hartley et al. 2010; Simpson et al. 2019).

Qualitative studies have indicated that adults with hearing loss value guidance from health professionals such as their general practitioner (GP) regarding managing their hearing (Laplante-Lévesque et al. 2012; Pryce et al. 2016). However, Australian data suggest that only 0.3% of GP consultations with adults aged 50 and over involve the management of a hearing condition, despite approximately one-third of this age group having a bilateral hearing loss (Schneider et al. 2010). In Australia, 87% of the population visits a GP at least once per year, and approximately half of these appointments involve adults aged 50 and older (Schneider et al. 2010; Britt et al. 2016). This high level of contact with adults most at risk of acquired hearing loss makes GPs ideally placed to initiate a discussion about hearing loss and refer at-risk adults to hearing care. Increasing the number of GP referrals of older adults to audiology has the potential to significantly increase the number of adults who receive appropriate hearing intervention, with likely subsequent positive effects on social connectedness, mental and physical health, quality of life, and healthy aging. This would also likely result in cost savings at personal, governmental, and societal levels (Deloitte Access Economics 2017).

Achieving effective behaviour change amongst health professionals requires an active, theory-informed, and evidence-based approach (Bauer et al. 2015). The field of implementation science provides several frameworks which facilitate identification and appropriate documentation of barriers and enablers to performing particular healthcare behaviours. By utilising these frameworks, factors found to be important in determining behaviour can be mapped to evidence-based interventions, leading to a greater chance of successful behaviour change (Michie et al. 2005). In this paper, we refer to two of these frameworks: the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF, Supplementary file S1) and the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behaviour (COM-B) model (Michie et al. 2011; Cane et al. 2012). As illustrated in Table 1, the TDF consists of 14 domains, allowing for detailed classification of factors that influence behaviour, while the COM-B can assist with understanding how these domains translate into clinical practice (Michie et al. 2011; Cane et al. 2012). These frameworks can be used together or in isolation (Ojo et al. 2019). In this study, we used the TDF to design a questionnaire and both the TDF and COM-B to analyse the data.

| COM-B component | Description | TDF domain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capability | The ability (psychological or physical) to perform the behaviour | Knowledge | |

| Skills | |||

| Memory, attention, and decision making processes | |||

| Behaviour regulation | |||

| Motivation | The underlying beliefs which guide a behaviour | Beliefs about capabilities | |

| Social/professional role and identity | |||

| Beliefs about consequences | |||

| Emotions | |||

| Goals | |||

| Intentions | |||

| Reinforcement | |||

| Optimism | |||

| Opportunity | Factors outside the individual which influence the perfomance of the behaviour | Environmental context and resources | |

| Social influences |

Aims

To increase the number of audiology referrals in general practice, we must first understand the factors that influence GPs’ referral patterns. The aim of this cross-sectional study was to generate an overview of the key barriers and enablers affecting GP referral behaviour in a sample of Australian GPs.

Methods

Questionnaire development

A systematic search of the current body of questionnaire and interview studies in the literature was conducted in January 2023, yielding 75 unique items (participant quotes or questionnaire items) across seven papers (Davine et al. 2025). These items were coded by two reviewers into the TDF, with items assigned to 10 of the 14 possible domains (Atkins et al. 2017). The content of these domains was then further refined via inductive coding into narrower ‘theme’ categories within each domain (Creswell and Creswell 2017). No set number of themes within each domain was determined prior to content analysis; rather, the total number of themes was determined by the diversity of content identified within each domain by two reviewers. The intent of this process was to consolidate the thematic content of all previously used questionnaire tools into a single, theoretical framework-informed questionnaire.

Huijg et al. (2014) provide a series of validated question ‘stems’ for each domain of the TDF, though final question stems were not able to be generated for all 14 domains. The available stems were adapted to align with the themes identified in the systematic review (Davine et al. 2025). In the case of domains where Huijg et al. (2014) did not provide validated question stems, question phrasing was determined via discussion and consensus amongst the research team.

Of the 19 themes identified from the systematic review, 17 could be converted into questions. No agreed-upon questions could be created for the domain of ‘skills’ or the theme of ‘knowledge of treatments for hearing loss’ due to overlap in content with other themes. We were also unable to generate a question for the theme of ‘unrealistic optimism’ without using leading phrasing.

To determine whether the proposed questionnaire was user-friendly and relevant to our target population, four, one-on-one ‘think aloud’ interviews with practising GPs were conducted. In these interviews, GPs were invited to complete the questionnaire in real time while participating in a recorded video call with a researcher. Participants were asked to speak aloud their thoughts and reactions as they completed the questionnaire, and to offer any suggestions for its improvement where relevant. Following these interviews, the questionnaire was further refined before distribution.

Recruitment and questionnaire distribution

The online questionnaire service Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) was used to host the questionnaire, which was open for 10 weeks from September to November 2023. The questionnaire link was distributed via online bulletins, newsletters targeting GPs with a research interest, direct emails to GP clinics, and posts in an Australian GP social media group. Responses were anonymous, but location data were stored to enable comparisons in responses between GPs in the state of Victoria (where the study was based) and non-Victorian GPs. Participants were offered a AUD75 honorarium for completing the questionnaire.

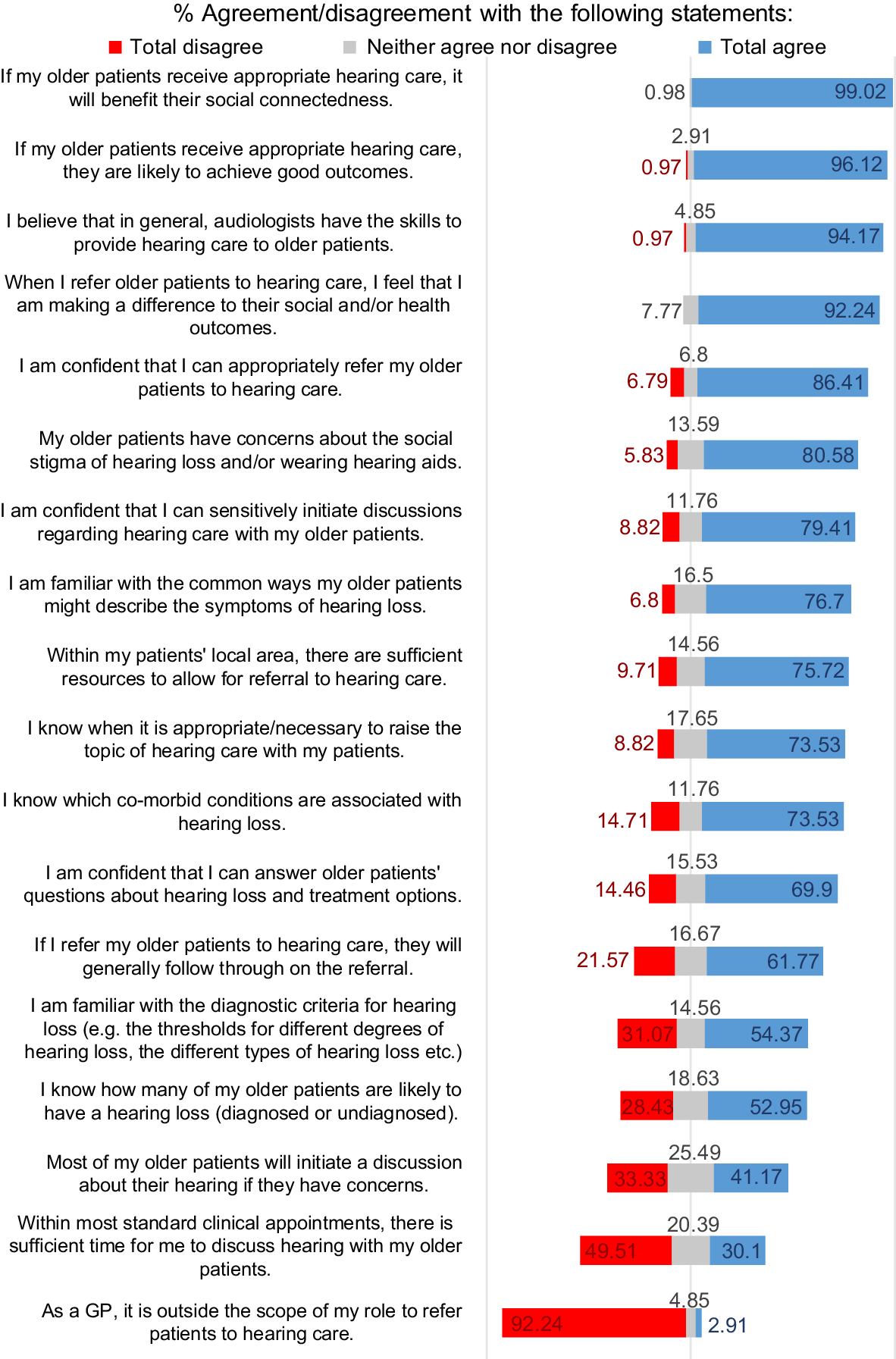

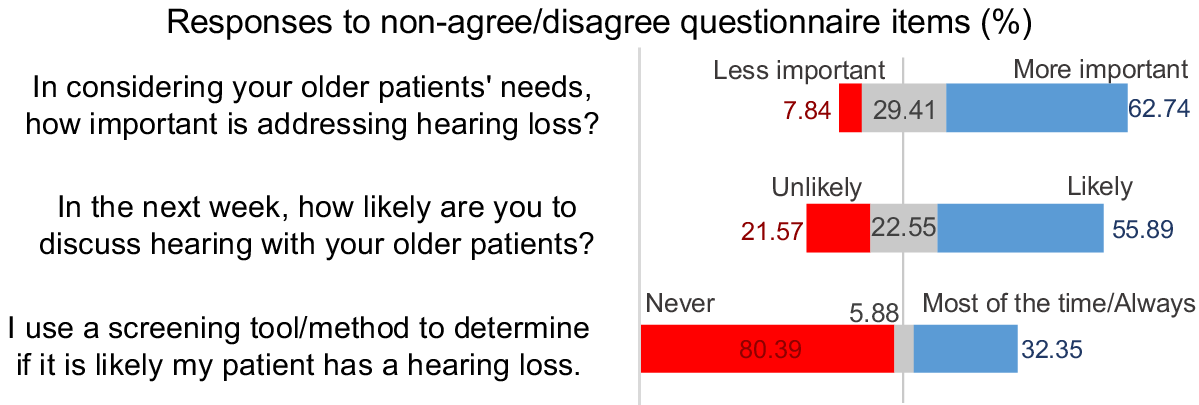

Eighteen Likert scale questions used a response continuum of ‘Strongly Agree’ to ‘Strongly Disagree’ (Fig. 1), while three others used different response options determined by the content of the question (Fig. 2). A final, open-ended question asked participants to respond to the prompt: ‘Do you have any other comments regarding barriers and enablers to hearing care referral that you would like to add?’. The full questionnaire is provided in the Supplementary material.

Analysis

Results were analysed using Minitab® Statistical Software (Minitab, LLC Pennsylvania). Likert scale data were ranked by percentage of total agreement, whereas thematic content from the free format question was ranked by number of occurrences. Content analysis of the free format responses was performed in the following order:

Results

Participant characteristics

One hundred and three responses were obtained, comprising 101 complete and two partially completed responses. Analysis of IP address data indicated 58 Victorian GP responses and 45 from interstate GPs. A Mann–Whitney test with Bonferroni corrections showed no significant differences in responses between groups to any question.

Participants estimated their typical caseload averaged 45.84% of adults aged 50 years and over (s.d. = 19.8, range = 5–85%). This is in line with data from a study of 485,300 Australian GP appointments reported by Schneider et al. (2010), of which 47.7% were with adults aged 50 and over.

Likert scale responses

Fig. 1 shows responses to the 18 ‘Strongly Agree’ to ‘Strongly Disagree’ Likert scale questions, ordered by total agreement score. The highest levels of agreement were observed for domains that related to respondents’ beliefs about the value and outcomes of hearing care referral, the skills of audiologists, the view that managing hearing loss was important in overall patient management, and that referring patients to hearing care was within the GP perceived scope of practice. Greater disagreement was found within domains that related to logistical concerns such as time and resources, as well as the respondents’ knowledge of hearing loss.

Fig. 2 shows the results of the three Likert scale questions that used different response options.

Most respondents reported feeling that hearing loss was a relatively high priority health condition to address, with a slightly smaller majority also reporting that they were somewhat or very likely to discuss hearing loss with older patients in the next week. Less than one-third of respondents had used a screening tool or other screening method for hearing loss with their older patients to guide their referral decisions.

Free format responses

Content analysis of the responses to the open-ended free format question: ‘Do you have any other comments regarding barriers and enablers to hearing care referral that you would like to add?’ yielded 25 themes, coded across 11 different TDF domains (Table 2).

| Domain | Theme | Count | Barrier count | Enabler count | Barrier/enabler (majority) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental context and resources | Cost of hearing devices and assessment A | 24 | 24 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Environmental context and resources | Local resources | 13 | 7 | 5 | Barrier | |

| Environmental context and resources | Lack of time | 8 | 8 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Social influences | Who initiates the discussion about hearing loss? | 8 | 7 | 1 | Barrier | |

| Beliefs about consequences | Beliefs about patient uptake of hearing rehabilitation | 8 | 6 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Goals | Relative importance of other health conditions | 7 | 7 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Social influences | Social stigma | 7 | 7 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Knowledge | Knowledge of costs and funding A | 6 | 6 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Social influences | Skills of other professionals | 6 | 5 | 1 | Barrier | |

| Knowledge | Familiarity with diagnostic criteria and tools | 5 | 5 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Emotion | Trust in hearing services A | 5 | 5 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Knowledge | Knowledge of treatments | 4 | 4 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Beliefs about consequences | Beliefs about hearing rehabilitation outcomes/efficacy | 3 | 3 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Social/professional role and identity | Communication between professionals A | 3 | 3 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Knowledge | Impacts and comorbidities | 3 | 2 | 1 | Barrier | |

| Beliefs about capabilities | Ease of discussion | 2 | 2 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Beliefs about capabilities | Familiarity with next steps | 2 | 2 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Knowledge | Knowledge of condition | 2 | 2 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Social influences | Patient acknowledgement of hearing/hearing problem A | 2 | 2 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Social/professional role and identity | Scope of other professional’s roles in managing hearing loss A | 2 | 2 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Social influences | Positive social models of hearing loss/hearing rehabilitation A | 2 | 0 | 2 | Enabler | |

| Social/professional role and identity | Scope of professional role in managing hearing loss A | 2 | 1 | 1 | Middle ground | |

| Memory, attention, and decision-making processes | Abnormal test results as a trigger for referral | 1 | 1 | 0 | Barrier | |

| Intentions | Intention to change future behaviour | 1 | 0 | 1 | Enabler | |

| Beliefs about consequences | Social outcomes of hearing rehabilitation | 1 | 0 | 1 | Enabler |

Responses to the free format questions focused on barriers more than enablers. Of these themes, eight were unique to this study and have not been formally identified in the current body of literature.

Data integration

All five of the highest-ranked themes from the Likert scale data related to enablers for referral, while responses to all but three of the Likert scale questions identified their respective theme as an enabler, albeit with varying degrees of agreement. There was no theme-level overlap between the highest-ranking enablers in the Likert scale and most frequently raised themes in the free format data (Table 3). However, there was some domain-level overlap, with ‘Beliefs about consequences’ occurring in both datasets. The only high-ranking Likert enabler to be raised at all in the free format responses was ‘Beliefs about the social outcomes of hearing loss’, which was raised by only one GP.

| Rank | Likert scale enablers | Likert scale barriers | Free format responses (all barriers) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TDF domain (COM-B) | Theme | TDF domain (COM-B) | Theme | TDF domain (COM-B) | Theme | ||

| 1 | Beliefs about consequences (M) | Beliefs about social outcomes of hearing care | Social influences (O) | Social stigma | Environmental context and resources (O) | Cost of hearing devices and assessment | |

| 2 | Beliefs about consequences (M) | Beliefs about hearing care outcomes and efficacy | Environmental context and resources (O) | Lack of time | Environmental context and resources (O) | Local resources | |

| 3 | Social influences (O) | Skills of other health professionals | Memory, attention and decision-making processes (C) | Use of a screening tool to guide referral | Environmental context and resources (O) | Lack of time | |

| 4 | Reinforcement (M) | No theme used – domain level question | Social Influences (O) | Relying on the patient to raise hearing concerns | Social influences (O) | Relying on the patient to raise hearing concerns | |

| 5 | Social/professional role and identity (M) | Scope of own role in managing hearing loss | Knowledge (C) | Knowledge of prevalence | Beliefs about consequences (M) | Beliefs about patient uptake of hearing care | |

M, motivation; O, opportunity; C, capability.

Of the data pertaining to barriers (or weak enablers), there was slightly more overlap, with both ‘lack of time’ and ‘relying on the patient to raise hearing concerns’ arising in both datasets. These overlapping themes are described below.

Lack of time

A total of 49.51% (n = 51) of GPs disagreed with the statement ‘Within most standard clinical appointments, there is sufficient time for me to discuss hearing with my older patients’, with a further 20.39% responding neutrally.

… this is often not a patient’s primary complaint and in the limited time frame of a standard consultation it therefore takes a backseat and/or is not talked about. (GP56)

In all eight instances of this theme arising in the free format data, the amount of time available in a consult was raised as a barrier to referral. Frequently, this was linked to having several health priorities competing for clinical time.

Relying on the patient to raise hearing concerns

A total of 41.17% (n = 42) of GPs agreed with the statement ‘Most of my older patients will initiate a discussion about their hearing if they have concerns’, which may indicate a reliance on the patient rather than the GP to raise hearing as a concern. A further quarter of respondents responded neutrally to this question, which may reflect uncertainty for GPs about whether it is appropriate for them to raise this topic in clinical practice.

I am mostly relying on patients bringing this up as an issue, or family members complaining about it. (GP23)

In seven of the eight occurrences of this theme in the free format responses, relying on the patient to raise hearing concerns occurred as a barrier to referral, with GPs reporting they typically relied on patients (or their family) raising hearing as an issue, rather than initiating the discussion themselves.

The themes of ‘Lack of time’ and ‘Relying on the patient to raise hearing concerns’ fall under the domains of environmental context and resources and social influences respectively, which in turn both fall under the COM-B category of ‘Opportunity’.

The remainder of the top five most frequently raised themes in the free format responses are described narratively below.

Hearing aids are very expensive for people, so often I feel what difference will it make if they cannot afford aids? (GP69)

GPs felt that the cost of hearing care was high, particularly for hearing devices. In all 24 occurrences, this was nominated as a barrier to referral, as well as a perceived reason for a lack of follow through on referrals by patients.

The nearest audiologist is 1.5 hrs away … (GP101)

The availability of a local audiologist was raised as a barrier in seven instances, and an enabler in five. This may be reflective of the breadth of settings in which respondents practised, as two participants who flagged access as a barrier noted that they worked in a regional setting.

I find a lot of my patients are hesitant to accept a referral for audiology as it is either ‘too much of a bother’ for what they consider a ‘normal’ aging phenomenon or they simply refuse to wear hearing aids due to stigma. (GP56)

In all eight occurrences of this theme, GPs expressed a belief that patients were not keen on taking up hearing care recommendations and may not follow through on a referral to audiology.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional questionnaire study, we explored Australian GPs’ views on 25 themes related to the referral of older adults to hearing care. Of these themes, eight had not been previously reported in the existing body of literature.

The two barriers that occurred across both the Likert scale data and the free format responses were ‘Lack of time’ and ‘Relying on the patient to raise hearing concerns’. It is of interest to note that when mapped to the COM-B, these themes fell under the umbrella construct, ‘Opportunity’. This is further reflected in the remainder of the results, which suggested that although GPs’ views of hearing care and its outcomes were generally positive, pragmatic issues, such as concern regarding the costs of hearing care and a lack of resources, were identified as significant barriers. This in turn suggests that GPs feel that the main barriers to referral are outside their control. For example, a GP may not have control over the length of appointment a given patient requests, which may in turn be determined by financial or time constraints experienced by the patient. However, although these types of barriers cannot necessarily be targeted directly, they provide important context in considering what may constitute a feasible intervention. For instance, for an intervention to be feasible in this context, it is likely that it would need to take little time.

The relatively low overlap in themes identified in the Likert scale data and the free format response data may suggest that there are further themes to be explored in this area. Future iterations of this questionnaire study incorporating these new themes, as well as greater qualitative investigation, may clarify the degree to which these factors influence GPs’ referral behaviour.

A 2022 systematic review identified the domains of ‘environmental context and resources’, ‘knowledge’, and ‘social influences’ as those most commonly reported as being important in studies of primary healthcare provider behaviour (Mather et al. 2022). This finding largely aligns with the themes observed in the free format responses in this study, as well as with the barriers identified in the Likert scale data. An interesting point of difference observed between this dataset and the systematic review results was the relative importance of ‘goals’ as a domain. Although this was the sixth most frequently raised barrier in the free format responses in this study, it was identified by Mather et al. (2022) as one of the least important themes across the 19 studies included in their review. The reason for this difference in outcomes is unclear and warrants further exploration.

An important strength of the current study is the breadth of themes we have been able to explore, both in the Likert scale questions, as well as those observed in the free format question responses. There is little work in this area to date, with a recent systematic review (Davine et al. 2025) finding that of the seven papers published on this topic, only one used a theoretical framework to systematically explore barriers and enablers to hearing care referral (Gilliver and Hickson 2011). By both building on the findings of a systematic review and using a theoretical framework, this study has, to our knowledge, identified the greatest number of themes in this area using a single questionnaire tool. Including qualitative analysis of open-ended free format question responses added eight novel themes to the body of knowledge (e.g. cost of hearing devices and assessment, trust in hearing services etc.), facilitating increased understanding of factors influencing GP referral to hearing care.

Potential limitations to this study are self-selection of participants and the anonymity of their responses. However, anonymity is also a strength of this study, as although anonymity limits the demographic data available, it may also encourage participants to respond more honestly, as their responses cannot be linked back to them (Patten 2016). Those who are interested in, or perhaps feel positively towards, hearing care and participating in research may have been more likely to respond to this voluntary questionnaire, creating a risk of bias. Offering a monetary honorarium for questionnaire completion may, however, have captured some respondents who were motivated by financial reward rather than by personal interest in this topic. Response bias is a frequent concern in all voluntary research, and evidence suggests that voluntary participation does not inherently lead to a biased dataset (af Wåhlberg and Poom 2015).

Conclusions

By consolidating the thematic content from several pre-existing studies, as well as adding eight new themes to the body of literature, this paper lays the groundwork for further intervention-focused research aimed at increasing the number of referrals from general practice to audiology. In particular, the new thematic content reflected in the free format responses different from that obtained from responses to the Likert-scale raises further areas to be explored in future qualitative research. The findings of this study will be further explored in a series of focus group discussions with GPs, which will then inform the co-design of behavioural intervention/s for use in clinical practice to address the low rates of hearing care referral in Australia.

Data availability

The complete results of this questionnaire study can be found within this paper and its supplementary materials.

Declaration of funding

This research received funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC, TRC grant 2015556, CI: Julia Sarant). This research was also supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship. The funding bodies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; in the decision to submit the article for publication; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the article.

References

af Wåhlberg AE, Poom L (2015) An empirical test of nonresponse bias in internet surveys. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 37(6), 336-347.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, O’Connor D, Patey A, Ivers N, Foy R, Duncan EM, Colquhoun H, Grimshaw JM, Lawton R, Michie S (2017) A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implementation Science 12(1), 77.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bauer MS, Damschroder L, Hagedorn H, Smith J, Kilbourne AM (2015) An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychology 3(1), 32.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bisgaard N, Zimmer S, Laureyns M, Groth J (2022) A model for estimating hearing aid coverage world-wide using historical data on hearing aid sales. International Journal of Audiology 61(10), 841-849.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S (2012) Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Science 7(1), 37.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Davine EC, Busby PA, Peters S, Francis JJ, Sarant JZ (2025) Barriers and enablers to general practitioner referral of older adults to hearing care: a systematic review using the theoretical domains framework. European Geriatric Medicine10.1007/s41999-024-01124-5

Genther DJ, Betz J, Pratt S, Kritchevsky SB, Martin KR, Harris TB, Helzner E, Satterfield S, Xue Q-L, Yaffe K, Simonsick EM, Lin FR, for the Health ABC Study (2014) Association of hearing impairment and mortality in older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 70(1), 85-90.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gilliver M, Hickson L (2011) Medical practitioners’ attitudes to hearing rehabilitation for older adults. International Journal of Audiology 50(12), 850-856.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hartley D, Rochtchina E, Newall P, Golding M, Mitchell P (2010) Use of hearing aids and assistive listening devices in an older Australian population. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 21(10), 642-653.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Huijg JM, Gebhardt WA, Crone MR, Dusseldorp E, Presseau J (2014) Discriminant content validity of a theoretical domains framework questionnaire for use in implementation research. Implementation Science 9(1), 11.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Laplante-Lévesque A, Knudsen LV, Preminger JE, Jones L, Nielsen C, Öberg M, Lunner T, Hickson L, Naylor G, Kramer SE (2012) Hearing help-seeking and rehabilitation: perspectives of adults with hearing impairment. International Journal of Audiology 51(2), 93-102.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cooper C, Fox N, Gitlin LN, Howard R, Kales HC, Larson EB, Ritchie K, Rockwood K, Sampson EL, Samus Q, Schneider LS, Selbæk G, Teri L, Mukadam N (2017) Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet 390(10113), 2673-2734.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Mahboubi H, Lin HW, Bhattacharyya N (2018) Prevalence, characteristics, and treatment patterns of hearing difficulty in the United States. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 144(1), 65-70.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mather M, Pettigrew LM, Navaratnam S (2022) Barriers and facilitators to clinical behaviour change by primary care practitioners: a theory-informed systematic review of reviews using the Theoretical Domains Framework and Behaviour Change Wheel. Systematic Reviews 11(1), 180.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A (2005) Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Quality and Safety in Health Care 14(1), 26-33.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R (2011) The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science 6(1), 42.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ojo SO, Bailey DP, Hewson DJ, Chater AM (2019) Perceived barriers and facilitators to breaking up sitting time among desk-based office workers: a qualitative investigation using the TDF and COM-B. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16(16), 2903.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pryce H, Hall A, Laplante-Lévesque A, Clark E (2016) A qualitative investigation of decision making during help-seeking for adult hearing loss. International Journal of Audiology 55(11), 658-665.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Schneider JM, Gopinath B, McMahon CM, Britt HC, Harrison CM, Usherwood T, Leeder SR, Mitchell P (2010) Role of general practitioners in managing age-related hearing loss. Medical Journal of Australia 192(1), 20-23.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Simpson AN, Matthews LJ, Cassarly C, Dubno JR (2019) Time from hearing aid candidacy to hearing aid adoption: a longitudinal cohort study. Ear and Hearing 40(3), 468-476.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Vancampfort D, Koyanagi A, Hallgren M, Probst M, Stubbs B (2017) The relationship between chronic physical conditions, multimorbidity and anxiety in the general population: a global perspective across 42 countries. General Hospital Psychiatry 45, 1-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wilson BS, Tucci DL, Merson MH, O’Donoghue GM (2017) Global hearing health care: new findings and perspectives. The Lancet 390(10111), 2503-2515.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |