Father and non-birth parent experience of child and family health services: a systematic review and meta-synthesis

Catina Adams A * , Shannon Bennetts A , Lael Ridgway A , Leesa Hooker A B , Christine East A Kristina Edvardsson A

A * , Shannon Bennetts A , Lael Ridgway A , Leesa Hooker A B , Christine East A Kristina Edvardsson A

A

B

Abstract

This study aimed to synthesise global research examining the experiences of fathers and non-birth parents using child and family health services, and to identify the facilitators and barriers to father- and non-birth parent-inclusive practice.

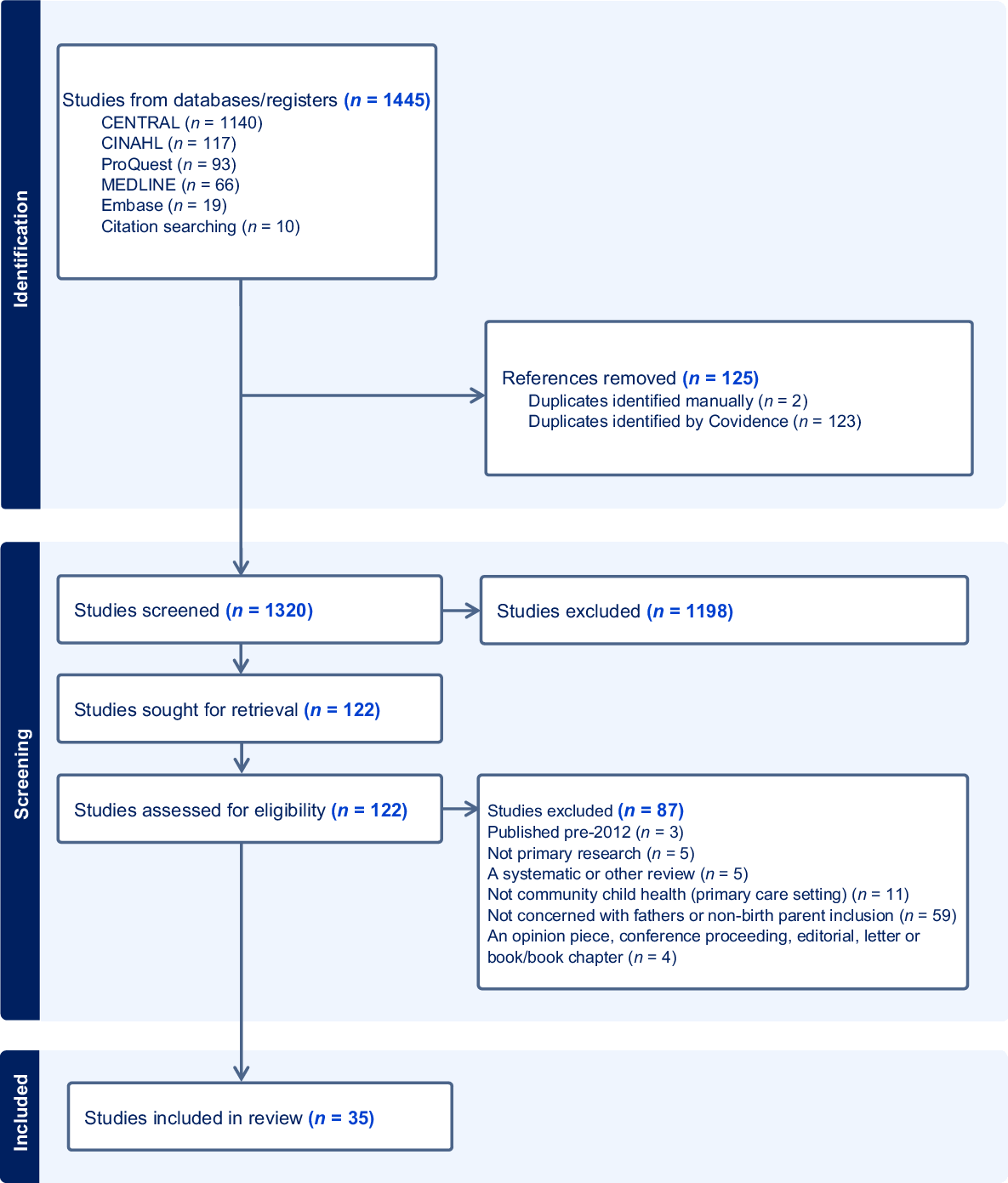

A systematic review, using the Joanna Briggs Institute mixed-methods approach, and meta-synthesis of the data were performed. We undertook a quality appraisal of the research using the Quality Assessment with Diverse Studies (QuADS) tool. An initial systematic search was conducted of four scientific databases (ProQuest Central, CINAHL, MEDLINE, EMBASE) in January 2023, and updated in February 2024. Results were reported according to the PRISMA guidelines with no patient or public contribution.

We identified thirty-five studies for inclusion. Thirty-one papers identified barriers to inclusive practice, such as program design (n = 15), traditional gender roles and gatekeeping (n = 11), and lack of workforce knowledge and skills (n = 11). Facilitators of inclusive practice included factors such as explicit inclusion (n = 14), support with transition to parenthood (n = 11), connection with other fathers (6), and attention to the father’s health and well-being (n = 13). The four papers that concerned same-sex parents identified additional and specific barriers experienced by same-sex parents, including discrimination and homophobic attitudes.

We found barriers and facilitators of father and non-birth parent engagement in child and family health services at individual, community, and health service levels, with organisational and cultural barriers impacting inclusive practice. Inclusive practice for fathers and non-birth parents entails the development of environments, policies, and programs that actively involve and support the father and non-birth parent in all aspects of parenting and family life. Strategies include systematic outreach to fathers and non-birth parents, customising activities to fathers’ and non-birth parents’ preferences, and addressing their needs.

Keywords: child and family health, fathers, inclusive practice, maternal and child health, meta-synthesis, non-birth parents, systematic review, transition to parenting.

Introduction

Father- and non-birth parent-inclusive practice is an approach that aims to actively involve and support fathers and non-birth parents, such as same-sex parents, in the upbringing and care of their children. This practice recognises and supports diverse family structures and all parents’ significant roles in a child’s development. Despite the presence of family-centred care policies and approaches in child and family health services, engagement with fathers and non-birth same-sex parents is often limited, and their health and well-being are often overlooked (Cabrera et al. 2018). Identifying the factors that hinder or enable inclusive practices involving fathers and non-birth parents is important for optimising child development and family well-being.

Existing literature tends to present a heteronormative view of ‘family’, primarily identifying the non-birth parent as male (Gruson-Wood et al. 2023). There is a lack of research exploring the impact of non-birth same-sex parents on child health and development, their well-being, and their support needs during early parenthood, particularly within the context of child and family health settings.

This systematic review synthesises research examining the experiences of fathers and non-birth parents using child and family health services. Child and family health services encompass a range of programs and resources designed to promote the well-being and development of children from birth to five years of age and their families. These services often focus on early intervention and support for families with additional challenges (Schmied et al. 2011).

We identify facilitators and barriers to father- and non-birth parent-inclusive practice, and strategies used by child and family health nurses and other healthcare practitioners to improve engagement.

Background

The World Health Organization emphasises the significance of father engagement in health promotion interventions for maternal and newborn well-being (World Health Organization 2015a). The transition to fatherhood brings physical, social, and emotional changes with a lifelong impact (Gold et al. 2020). However, men’s experiences of pregnancy, labour, and early fatherhood can be a time of marginalisation and vulnerability (Baldwin et al. 2021). Poorly designed perinatal support and poorly delivered services can exacerbate this experience.

Father-inclusive practice refers to services designed and implemented to support the roles and experiences of fathers and address the needs of women and children (Allport et al. 2018). Father-inclusive practice is recommended internationally (Commonwealth of Australia 2009; World Health Organization 2015b), with the advantages of including fathers in child and family health care identified (Cardenas et al. 2022). Greater father involvement is linked to better developmental outcomes for children (Kroll et al. 2016), improved paternal health and well-being, improved family and couple relationships (Cabrera 2020), and support for families in the transition to parenthood (Diniz et al. 2021).

Child and family health services play a role in connecting with families from their child’s birth and often maintain their involvement until the child enters school. A trust-based relationship with child and family health nurses can foster open communication, allowing families to disclose sensitive and challenging personal issues, such as mental health problems or family violence (Adams et al. 2021). Child and family health services have traditionally focused on the mother and child. Changing gender roles and increased expectations of fatherhood have led to an awareness that the whole family benefits when fathers and non-birth parents are actively included in child health and parenting support activities (Diniz et al. 2021).

The increased interest in the father’s role arises from socio-economic changes, such as the increased number of women in the labour force, as well as diversity in family structures and dynamics, which challenge beliefs about parental roles, particularly for fathers (Diniz et al. 2021). Over the past two decades in the United Kingdom, the number of men who act as their children’s primary carer has risen tenfold, with more than 91% taking some time off after the birth of their child (Machin 2015). Nevertheless, over half of Australian fathers work more than 45 hours per week postpartum (Cooklin et al. 2015), so balancing fathering and breadwinning responsibilities brings challenges. In Australia, same-sex couples account for 1.4% of all couples living together. About one in five same-sex couples have children, with female same-sex couples more likely to have children (27.7%) than male same-sex couples (7.0%) (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2022).

Men’s mental health and well-being during their transition to fatherhood is an important public health issue that is under-researched (Baldwin et al. 2021). Rates of depression and anxiety among men are high, with up to 25% experiencing a diagnosed mental health disorder in their lifetime and 15% experiencing a disorder in the previous 12-month period. From 15 to 44 years of age, the leading causes of disease burden in males are suicide, self-inflicted injuries, and alcohol use disorders (Terhaag et al. 2020).

Postnatal depression in fathers is associated with emotional and behavioural problems in their children at three years of age, particularly in boys (Ramchandani et al. 2013). Depression affects fathers’ capacity to engage in quality father–child interactions, which may contribute to poorer cognitive, behavioural, social, and emotional development in their children (Cui et al. 2020).

Interventions aimed at engaging fathers or non-birth parents are effective in strengthening positive lifestyles and parenting behaviours (Comrie-Thomson et al. 2021). Expanding research highlights the significance of fathers’ long-term involvement with their children, so policymakers and healthcare practitioners are increasingly seeking methods to encourage fathers’ engagement during early childhood (Osborne et al. 2022).

Methods

Design

We followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) mixed-methods approach to systematic reviews (Pearson et al. 2015) and PRISMA guidance in reporting the review (Page et al. 2021).

Search methods

The systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022358908). Four databases were searched in January 2023: ProQuest Central, CINAHL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE. The search was updated in February 2024.

The database searches used keywords: child and family health nurse (and its international equivalents), family support (and its synonyms), parent (and its synonyms), and engagement and inclusion (see Table 1). Inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in Table 2.

| Database | Keywords | |

|---|---|---|

CINAHL PROQUEST MEDLINE EMBASE GOOGLE SCHOLAR (grey literature) Limiters -

| Maternal and Child Health nurs* OR Public health nurs* OR Health visit* OR Child and family health nurs* OR Community health nurs* OR Plunkett | |

Family support OR parenting ORhealth educ* OR health promot* | ||

Parent* OR Father* OR non-birth*parent OR non-birth* partner | ||

Engag* OR inclusion OR inclusive practice OR consumer |

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

The review will include papers that: 1. Report primary research. 2. Are peer-reviewed. 3. Are published from 2012 in the English language. 4. Are studies in high-income settings. 5. Report findings of any aspect of father-/non-birth parent-inclusive practice in child, family, and community health settings (children 0–5 years of age). 6. Relevant doctoral dissertations. | A paper will be excluded if it is: 1. Published pre-2012. 2. Only published in another language than English. 3. An opinion piece, conference proceeding, editorial, letter or book/book chapter, or case reports. 4. Set in hospital or acute nursing settings. 5. Concerning practice with children >5 years. 6. A systematic or other review. |

Search outcome

The second author (SB) conducted the searches, identified papers from the selected databases, and imported the files into COVIDENCE (Covidence systematic review software; Veritas Health Innovation). Duplicates were removed, and all five authors applied the predetermined exclusion criteria to screen titles and abstracts. The first and second authors (CLA and SB) reviewed the full text of the included papers and screened them for inclusion or exclusion. A third assessor (KE) reviewed papers with conflicting assessments.

Data extraction

We designed a data extraction template and used the template to describe the following study characteristics of the included texts (Supplementary Table S1): author(s), title, year of publication, the country where the study was conducted, aim, study design, analysis method, study funding source, possible conflict of interest for study authors, inclusion and exclusion criteria, number of participants, gender, summary of findings recommendations, and strengths and limitations of the study as described by the authors.

Quality appraisal

We used the Quality assessment with diverse studies (QuADS) tool to assess the quality of studies within systematic reviews that include diverse study designs (Harrison et al. 2021). We opted for this single tool for ease of reporting instead of the two tools described in the Prospero protocol (CRD42022358908): the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist to assess qualitative research studies and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for evaluating quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies.

Using the QuADS, we determined that all the studies were methodologically sound, with only minor concerns. Overall, the studies demonstrated minor issues with recruitment, a lack of detail around data collection and analysis, and missing information about stakeholder involvement (Supplementary Table S1).

Synthesis

We defined the dataset as content from the Results or Findings section of the papers (including direct quotations from participants and key concepts or themes as interpreted by study authors). Thomas and Harden (2008) recommend this approach to qualitative synthesis: (i) coding the data, (ii) preserving the original language, (iii) grouping the data into descriptive codes, and (iv) identifying themes.

We used NVivo (Lumivero 2023) to analyse data and perform the meta-synthesis. The first author (CLA) developed themes inductively, comparing data from each study for similarities and differences. A second reviewer (SB) reviewed the coding spreadsheets, and any differences in opinion about the descriptive themes were discussed with a third reviewer (KE) to achieve consensus.

Results

The search generated 1445 records (125 duplicates), of which 1198 were excluded during title and abstract screening. We assessed 122 full-text papers for eligibility, which resulted in a final sample of 35 papers published between January 2012 and February 2024 that described father- and non-birth parent-inclusive practice in a child, family, and community setting (Page et al. 2021). As summarised in Table 3, 31 of the 35 included papers focused on fathers (as the non-birth parent) and four focused on lesbian non-birth parents. Studies were conducted in eight countries, most commonly in Australia (n = 11), the UK (n = 8), and the USA (n = 7). Fig. 1 depicts the papers presented following the PRISMA guidelines (Page et al. 2021).

| Characteristic | Results from studies | |

|---|---|---|

Country n = 35 | Australia = 11 Canada = 2 Finland = 1 Norway = 1 Singapore = 1 Sweden = 4 United Kingdom = 8 United States = 7 | |

Concerning the experience of fathers or lesbian non-birth parents (LGBTQI+) n = 35 | Fathers = 31 LGBTQI+ = 4 | |

Research method n = 35 | Multi method = 8 Qualitative = 19 Quantitative = 8 | |

Participants n = 35 | Fathers = 9 Mothers = 2 Lesbian mothers = 3 Parents = 8 Health care workers = 9 Both parents and health care workers = 4 | |

Year of publication n = 35 | 2012 = 1 2013 = 1 2014 = 3 2015 = 3 2016 = 4 2017 = 2 2018 = 3 2019 = 7 2020 = 2 2021 = 4 2022 = 3 2023 = 2 |

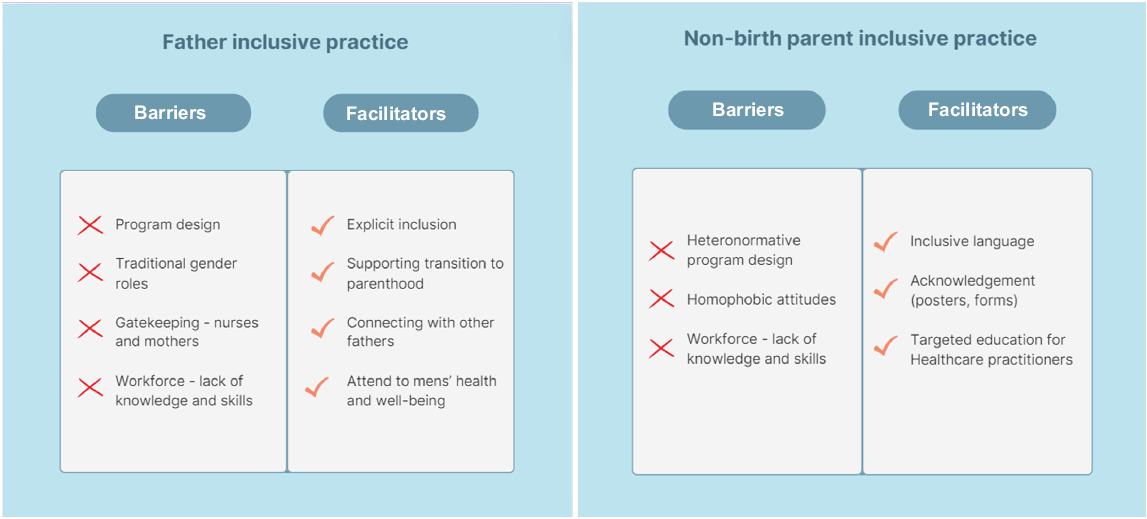

The following themes and sub-themes were identified (Fig. 2 and Tables 4, 5):

Barriers to father-inclusive practice, including program design, traditional gender roles, gatekeeping, and lack of workforce knowledge and skills.

Facilitators of father-inclusive practice, including explicit inclusion, support with transition to parenthood, connection with other men, and attention to men’s health and well-being.

Same-sex parents, including the parent experience and barriers and facilitators for non-birth parent-inclusive practice.

Table 5 summarises the synthesised research with illustrative quotes.

| Barriers to Father-inclusive practice | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program design | The service hours of Monday to Friday, 9 am−5 pm, coincide with the working hours of most fathers in paid employment (Humphries and Nolan 2015; Laffar and Elliott 2021). It is difficult for fathers to attend appointments and engage with health services operating only during business hours (Rominov et al. 2018). Many fathers said they would have liked to attend but could not because of income-generating work commitments (McGinnis et al. 2019; Forbes et al. 2021). Fathers may be more likely to attend parent groups if they occur in the evening, are run by men, and consist primarily of fathers (Wells et al. 2013). Strategically including fathers may require changes in schedules (e.g. to include more evening or weekend visits) (Stargel et al. 2020); however, this may impinge on nurses’ own family life. | As identified by Osborne et al.: Fathers employed during the day may be unable to attend home visits, but this does not necessarily represent their lack of desire to be engaged in home visiting (Osborne et al. 2022, p. 13). | ||

The names of services, such as the ‘Maternal and Child Health Service’ or ‘Mums and Bubs’ group, further excluded fathers and non-birth parents (Clifford-Motopi et al. 2022). Describing perinatal services as ‘woman-centred’ rather than ‘family-centred’, new and expectant mothers were almost exclusively identified as the client or patient, with minimal father involvement (Carlson et al. 2014). Systems for recording family information often did not include fathers, so children’s records and routine letters referred only to mothers (Humphries and Nolan 2015). This meant that family nurses were unlikely to engage with fathers and, conversely, fathers with nurses (Humphries and Nolan 2015). Nurses identified workforce pressure, with increasing responsibilities and fewer resources | Participants expressed frustration regarding limitations imposed by services, which reduced their ability for early intervention. One participant expressed frustration that she could barely find the time to work with mothers, never mind the additional challenge of working with fathers (Laffar and Elliott 2021, p. 248) | |||

Many fathers felt that society paid lip service to involved fatherhood rather than genuinely investing in its implementation and success (Machin 2015). Mother-centric language in written resources such as pamphlets and posters increased their sense of exclusion (Rominov et al. 2018). Fathers identified a lack of father-specific resources and a sense of being excluded from traditional mother-focused resources and models of care (Machin 2015). For example, several fathers emphasised targeting information on breastfeeding to fathers, rather than generic information (Sherriff et al. 2014). | One father referred to: The lack of visibility or lack of communication and, you know, when you go to the appointments at the hospital, there’s, you know, all of the literature and all of the stuff which is on the walls and is about more for the mother (Baldwin et al. 2021, p. 14). | |||

| Traditional gender roles and gatekeeping | One-third of the nurses in de Montigny et al.’s (2020) study felt that mothers are naturally better than fathers at bonding with a baby and providing a secure attachment relationship. However, following the nurses’ participation in a reflexive workshop, several beliefs about families were modified, and many nurses began reflecting on fatherhood and identifying and deconstructing prejudices or preconceived ideas about fathers. Several professionals became aware of their prejudices and discriminatory behaviours towards fathers (de Montigny et al. 2020). They learnt how important father involvement is for children and fathers themselves. Fathers frequently stated feeling excluded or marginalised during appointments (Forbes et al. 2021, 2023), to the point of feeling unwelcome (Wells et al. 2013). Men described being perceived as ‘useless’ and feeling like a ‘bit of a spare part’ (Baldwin et al. 2021). Men’s feelings of exclusion could negatively impact their ability to connect with their children and successfully transition into fatherhood (Clifford-Motopi et al. 2022). They described how they felt that their role as a co-parent was not acknowledged well enough in the healthcare system, resulting in feelings of marginalisation (Rominov et al. 2018). It is worth noting that women sometimes acted as ‘gatekeepers’, preventing nurses from having direct contact with fathers (Laffar and Elliott 2021). Women in one study preferred that their partners were not present, describing the assessment process as ‘women’s business’ and that they felt more comfortable and could speak more freely when their partners had left the room (Hjalmhult et al. 2014; Rollans et al. 2016). Other women were happy for their partners to go with them but usually did not see it as important enough for them to miss work to attend (Forbes et al. 2021). | In any case, I think that’s what the workshops did for me. Because they were saying that fathers, they’re, I don’t remember the term, but they stimulate their child. But children can also stimulate their father. It’s on both sides, and goes both ways (de Montigny et al. 2020, p. 1007). | ||

| Workforce lack of knowledge and skills | Some professionals admitted they had not suspected that some fathers who appeared indifferent might actually be ‘interested, attentive, communicative and eager to learn’ (de Montigny et al. 2020, p. 1008). Several professionals reported trying to adapt their discourse, taking into account approaches that work best with fathers, for example, by using humour (de Montigny et al. 2017). However, there were indications that many staff were not aware of their stereotypical view of men (Cooke et al. 2019). Nurses identified a need for dedicated training to feel more comfortable engaging with fathers and responding to their specific support needs (Wells et al. 2013; Humphries and Nolan 2015; Shorey et al. 2017). Mother-centred nurses often did not know how to connect with fathers or what to offer them (Carlson et al. 2014). Many nurses felt they needed education to identify fathering influences that promote or hinder child and family outcomes. These influences might form targets for intervention within the context of home visiting services (Guterman et al. 2018). Fathers wanted more information to feel better prepared and better supported when things did not go as planned (Rominov et al. 2018). The importance of multiple formats, including online resources and apps, to access resources and support was also recognised (Boykin et al. 2022; Clifford-Motopi et al. 2022). | Reflecting on the obstacles experienced by fathers, the professionals recognised the need to find better ways to connect with them. The reflexive workshops also made the professionals aware of the importance of reaching out to the father rather than simply waiting for the father to request services (de Montigny et al. 2020, p. 1011) | ||

| Facilitators of father-inclusive practice | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit inclusion | Midwives and Child and Family Health nurses used simple strategies to include partners in antenatal or postnatal visits. For example, they greeted the partner by name, demonstrated sensitivity to the concerns of the woman and the partner, and created opportunities to discuss their feelings about becoming parents (Rollans et al. 2016). Some fathers felt involved during the consultations and described feeling ‘very much part of the conversation’. Some services focused more on the physical environment (waiting room posters, words used, program names, etc.) to ensure fathers felt recognised and at home (de Montigny et al. 2020). Other strategies included buying magazines geared towards men for the waiting rooms, having parent group meetings in the evenings and having a male lead some parent group meetings (Wells et al. 2021). | One father said: I was being listened to, they were asking me specific questions as well. Not just about me but about how I was perceiving my wife’s state of mind or physical exhaustion to be (Baldwin et al. 2021, p. 14) | |

Some research identified that participation measures needed to expand beyond ‘attendance’ at appointments. Mothers reported that most fathers participated in activities such as asking the mother questions about the home visit or practising lessons after the visit – activities not observable and, therefore, not reported by a home visitor. In contrast, just over one-third of fathers participated in home visits – the activity most measured as an indicator of father participation (Osborne et al. 2022). Fathers in Hrybanova et al.’s (2019) study recommended that healthcare practitioners should find ways for fathers to participate and engage with the programs, such as being addressed and included in conversations and being asked to perform tasks during the visits, such as holding, weighing, and undressing the children. | I guess it’s about adequately signposting that there are services available in the moments when they might be needed. If it is a phone call, it’s part of that phone call being ‘Oh, we also have a drop-in center,’ or ‘Oh, you can also go here and speak to someone face-to-face. Here are the dad’s groups or whatever you can join and chat to other fathers.’ Making those options obvious and accessible is needed (Rominov et al. 2018, p. 464). | ||

Engagement strategies could include collecting contact information for the child’s father (especially important for non-resident fathers), leaving (or mailing) materials specifically for fathers to use outside of the visit, and developing specific programs in the evenings and weekends to engage fathers (Osborne et al. 2022). Other examples of engagement included fathers’ groups and antenatal classes facilitated by a father, services provided outside of normal business hours, visual demonstrations, online information, and hard-copy resources (Rominov et al. 2018). The fathers’ groups appeared to have the biggest impact on fathers’ sense of equality in the family, increasing self-confidence, addressing feelings of loneliness, creating a sense of connection and belonging, providing access to and finding resources, and broadening their social network (Carlson et al. 2014; Guterman et al. 2018; Wells et al. 2021). First Nations fathers wanted a stronger male presence in maternity and early childhood services, including a First Nations male worker to talk to and a men’s group to connect them with other First Nations fathers (Clifford-Motopi et al. 2022). | Those who had found material written specifically for men commented on the reassurance it provided and the helpfulness of the information in that format (Ross et al. 2012; Rominov et al. 2018). Several fathers discussed how incorporating father-specific information into classes would facilitate their receptivity to information and encourage them to become more involved (Rominov et al. 2018). | ||

| Supporting the transition to fatherhood | Nurses described changing societal views about fatherhood and fathers’ ‘friends telling them how important it is that they are involved with their children’ (Wells et al. 2021, p. 758). As fathers become aware of quality parenting and co-parenting practices, they may become more aware of their parenting limits (Guterman et al. 2018). | Educating fathers on topics such as infants and parenting and having them reflect on their own childhood and the need to address deficits experienced when fathered by their fathers, helped fathers to better ‘understand’ and ‘attach to’ their infants/children (Parry et al. 2019, p. 4). | |

| In another study, young men expressed concerns about their lack of skills in basic childcare activities, such as making up feeding bottles, bathing and handling infants. They said they would have benefited from further guidance and support in the lead-up to the birth and immediately after (Ross et al. 2012). A lack of information and support about alternatives to breastfeeding and how to support their partner in this process was identified as a significant gap for fathers (Rominov et al. 2018). | Fathers described a need for additional support in the early parenting period to assist with the multitude of challenges a newborn baby brings, such as developing a sleep routine, coordinating work schedules, renegotiating social commitments, and managing changes in the couple’s relationship (Rominov et al. 2018, p. 464) | ||

| Fathers often feel secondary or invisible in traditional parent groups (Wells et al. 2021). Gender-specific parent groups or fathers’ groups may provide an inclusive space for fathers to discuss their transition into parenthood (Parry et al. 2019; Wells et al. 2021; Clifford-Motopi et al. 2022). | As described by a male participant: I think it would’ve been nice if there were some men in some of those classes to say …. ‘Hey guys, this is what you do.’ (Carlson et al. 2014) | ||

| Connection with other fathers | Fathers appreciated hearing the prenatal parental information from male-led fathers’ groups and liked meeting other fathers (Campbell et al. 2018; Wells et al. 2021). A fathers’ group offers a safe space for men to connect with other fathers, likely reducing their internalised pressure to manage these stressors independently and their risk of adopting negative coping mechanisms (Clifford-Motopi et al. 2022). Fathers’ group leaders observed that fathers’ groups could increase the fathers’ reflection about parenthood, influence discussions regarding equality and the co-parenting relationship, and benefit the fathers’ relationships with their partner and child (Parry et al. 2019; Wells et al. 2021). Fathers meeting with other fathers helped them to feel less alone regarding their situation (Boykin et al. 2022; Parry et al. 2019) | As described by Carlson: The relationships between individuals are the medium in which learning takes place. Applied to first-time fathers and the transition to fatherhood, social learning suggests that men become fathers in relation to others, including current relationships with other fathers, as well as the social others in their lives. It is these mechanisms of observation, imitation, and modelling that shape who men become as fathers (Carlson et al. 2014). Other benefits of a fathers’ group were: … a source of reassurance that support was available should they require it, that parenting skills could be learnt there, that knowledge on the practical issues involved in parenting, like finances and budgeting, could be shared, that being with young men in similar situations to themselves would be beneficial, and that various fears or worries held could be aired in a supportive environment (Ross et al. 2012). | |

| Attention to men’s health and well-being | Participants suggested that engaging fathers in healthcare consultations can be an opportunity to connect men to services to support their well-being and psychological journey towards becoming fathers (Forbes et al. 2021). | From a young father expecting his first baby: reframing the whole thing as getting help for yourself is a way of helping your baby might be a good way of going about it (Rominov et al. 2018, p. 463). | |

| Men were keen for healthcare practitioners to take an interest in them and what was happening in their lives (Riggs et al. 2016). However, 90% of nurses in de Montigny et al.’s (2020) study admitted they rarely noticed when a father was experiencing distress, and fewer than one in five reported having offered support to a father in the past year. | It was mainly just kind of, you know, the odd jokes, you know, joke around as if it was my job to change the nappies, or, you know, look after … I have to look after my wife and the baby. So, I don’t have any sort of recollection of staff or health professional’s kind of taking my health into consideration” (Baldwin et al. 2021, p. 14) | ||

| Non-birth parents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers | Respondents generally felt there needed to be a shift in the healthcare paperwork accompanying an admission to an early parenting service, as the current paperwork is not flexible enough for diverse families. For example, forms that say ‘mother’ and ‘father’ do not allow for variations in family diversity (Bennett et al. 2017). Recognition involves professionals listening and reflecting on the language the family uses and making sure that parents are called by their own parenting names (Kerppola et al. 2019). | Being invisible, secondary, or left outside included a lack of recognition of parents’ gender identity, parental role, or even their legal status as parents. Participants reported that they did ‘not fit into the regular mould’ because almost all routines were based on and planned around heterosexual couples or families with two parents (Kerppola et al. 2019) | |

Barriers to father-inclusive practice

Barriers to father engagement in child and family health services were identified at the individual, community, and health service levels (de Montigny et al. 2020; Forbes et al. 2021). Organisational and cultural barriers were identified as factors impacting father-inclusive practice (Humphries and Nolan 2015). Participants felt that the predominantly female workforce in child and family health services negatively impacted engagement with fathers (Humphries and Nolan 2015; Laffar and Elliott 2021). The policy and practice orientation of the service towards fathers was also a crucial factor. Because the mother is explicitly named as the primary client in some services, this created uncertainty about the relationship with the fathers (Ferguson and Gates 2015).

Fathers felt that there was a systemic issue of them being symbolically, but not practically, recognised and supported by the child health field (Cooke et al. 2019). Several authors raise issues of nurses’ gatekeeping, maternal gatekeeping, and feminised environments as major barriers to including fathers (Wells et al. 2013; Cooke et al. 2019; de Montigny et al. 2020). The feminised environment was identified as a result of the predominantly female workforce in Child, Family, and Community nursing internationally. For example, in Victoria, Australia, there are only two male nurses in a workforce of over 1800 nurses.

Maternal or nurse gatekeeping arises when one person subtly or overtly limits or withholds information, resources, or opportunities. Even though parental gatekeeping can be engaged in by fathers as well as by mothers, the literature has focused almost entirely on maternal gatekeeping (Schoppe-Sullivan and Altenburger 2019). This relates to the prescribed gender roles for men and women, especially with respect to parenting, and the extent to which parents’ identities are tied closely with societal expectations regarding gender and parenting.

Barriers to fathers’ involvement may be amplified for men from minority groups. Culturally diverse fathers are positioned at an intersection of two groups that each experience barriers to engaging with perinatal services (Forbes et al. 2023). Barriers for culturally diverse fathers include limited access to transportation, lack of confidence in speaking English (Forbes et al. 2023), and difficulty navigating a new healthcare system while dealing with settlement challenges (Riggs et al. 2016). Participants spoke about the loss of extended family through migration, with new parental roles and the need to establish ‘family-like’ relationships with friendship groups in Australia (Forbes et al. 2023).

First Nations fathers wanted a stronger male presence in maternity and early childhood services, including a First Nations male worker to talk to and a men’s group to connect them with other First Nations fathers (Clifford-Motopi et al. 2022).

Common barriers to better engagement with fathers included a predominantly female healthcare workforce and healthcare practitioners’ lack of confidence to engage with fathers (Humphries and Nolan 2015). Some care providers felt that it was not their role to address the needs of men or that they were not equipped with the information the men were seeking (Riggs et al. 2016; de Montigny et al. 2020). When professionals believed the father had little interest in caring for their child, this affected their attitude towards him in their interactions, thereby perpetuating the phenomenon (de Montigny et al. 2020).

de Montigny et al. (2020) suggested that female professionals may benefit from interventions to increase their perceived self-efficacy in working with fathers. The results also indicated that the frequency of contact with fathers was positively associated with perceived self-efficacy. The strength of de Montigny et al.’s (2020) study is that it examined the links between acquiring new knowledge, developing and adopting beliefs, and integrating these two components into the professional practices implemented by healthcare practitioners.

Facilitators of father-inclusive practice

Inclusive practice for fathers involved creating environments, policies, and programs that actively engage and support fathers in various aspects of parenting and family life. Strategies used include systematic outreach to fathers, changing the timing of visits, employing fatherhood coordinators, tailoring activities to meet fathers’ preferences, and advocating for their needs (McGinnis et al. 2019). Engaging men at appointments was particularly important as this enabled trust to be established (Riggs et al. 2016), creating a culture of involved fathering with the concept of the father as a co-parent (Machin 2015).

Fathers identified that they needed support in their transition to parenthood (Shorey et al. 2017; Parry et al. 2019; Baldwin et al. 2021; Boykin et al. 2022). Ferguson and Gate’s (2015) study explored the experiences of vulnerable families being home visited in the Family Nurse Partnership program in the U.K. A lack of knowledge about parenting and the additional socioeconomic challenges of most of the men in this program left them feeling unprepared for fatherhood (Ferguson and Gates 2015).

Fathers identified a need for resources and support regarding communication skills, expressing their needs, managing conflict, and managing time to help them navigate these changes. A desire to know what resources were trustworthy was an important support need for fathers (Rominov et al. 2018). Aspects that would support their transition to fatherhood included information about fathers’ groups, childcare and support services, ‘feeding and general how-to-dos for caring for the baby’, tailored information for fathers, ‘online videos and bitesize information’, and preparation for changes in new fatherhood (Baldwin et al. 2021).

A key theme evident in men’s narratives was that becoming fathers and feeling love and responsibility towards their babies had changed them (Ferguson and Gates 2015) and that there were limited support options for men facing difficulties with the transition to fatherhood (Cooke et al. 2019). Fathers suggested reminding them that sleep interruptions, decreased sleep, fatigue, and changes to individual free time and intimacy can be expected during this time and may affect their health (Fisher et al. 2016; Boykin et al. 2022).

Fathers’ groups had a positive impact on their relationship with their partner and child (Shorey et al. 2017; Wells et al. 2021), assisting fathers to develop and maintain positive and productive relationships with their children through improved knowledge and understanding (Parry et al. 2019).

According to fathers, child and family health practitioners should enquire about fathers’ mental health and well-being, and ask direct questions as they do with mothers (Baldwin et al. 2021). Engaging fathers in their children’s health may provide an opportunity to engage fathers in their own health care (Boykin et al. 2022). Men’s needs and worries were rarely addressed (Riggs et al. 2016; Wells et al. 2021). To fulfil fatherhood roles and be the best father possible, some men described how they needed to acknowledge and move on from past loss, trauma, and mistakes (Clifford-Motopi et al. 2022). Parry et al. (2019) studied an Antenatal Dads and First-Year Families program in which the topics of mental health and suicide were actively discussed (Parry et al. 2019).

A common theme was the importance to the men of being able to discuss the sensitive subject of mental health and suicide without their partners present, which suggests that in a mixed or partnered meeting format, they may have remained quiet (Parry et al. 2019). Another study highlighted the negative stigma and attitudes that fathers may face about mental health and help-seeking (Rominov et al. 2018).

Recruiting and engaging fathers may be particularly challenging for healthcare practitioners working with young parents, given variations in their relationship status, residential status, or co-parenting relationship (Stargel et al. 2020). Perceived exclusion deterred some young men from attending further appointments, discouraging them from being as involved as they would have liked (Ross et al. 2012).

The relationship between parents significantly affected the level and nature of paternal involvement (Ferguson and Gates 2015). Fathers wanted to offer emotional support to their partners, and they felt that going to classes and appointments together supported the relationship (Forbes et al. 2021). For this reason, one study recommended a more explicit focus on strengthening family relationships and co-parenting (McGinnis et al. 2019).

Non-birth parents

The four included papers related to lesbian non-birth mothers identified additional and specific barriers and facilitators experienced by same-sex parents. These papers found that lesbian parents experienced discrimination and homophobic attitudes held by some nurses or other healthcare practitioners (Bennett et al. 2017). These negative attitudes were often associated with more conservative nurses with strong religious views (Bennett et al. 2017). The parents identified that targeted education was needed to assist in increasing awareness and sensitivity related to the challenges faced by LGBTQ parents in their parenting role (Bennett et al. 2017). According to the participants in Bennett et al. (2017) study, promoting acceptance of diversity and the inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender families in planning, developing, evaluating, and accessing early parenting services is required.

Brochures, medical records, and forms that provide only normative options for families, parents, and genders, heteronormative assumptions, and the use of heterosexist language meant that this group were either invisible or secondary in this system (Kerppola et al. 2019).

The findings of these papers show that the healthcare services accessed by the participants exhibited predominantly heterosexual assumptions (Kelsall-Knight and Sudron 2020). Non-biological mothers felt unacknowledged during interactions with nurses or healthcare practitioners (Engström et al. 2019; Kelsall-Knight and Sudron 2020) and felt disenfranchised due to their non-biological parent status (Kelsall-Knight and Sudron 2020). Some experiences were inclusive, but the majority left them feeling insignificant, marginalised, and somehow ‘less of a mother’ (Kelsall-Knight and Sudron 2020).

Discussion

This systematic review examines the literature on inclusive practices for fathers and non-birth parents. We found barriers to father and non-birth parent engagement in child and family health services at individual, community, and health service levels, with organisational and cultural barriers also impacting father- and non-birth parent-inclusive practice.

Our review emphasises that creating an inclusive environment for fathers and non-birth parents involves developing policies and programs that actively engage and support them in every aspect of parenting and family life. Effective strategies include systematically contacting fathers, scheduling visits at convenient times, hiring fatherhood coordinators, tailoring activities to suit fathers’ preferences, and addressing their specific needs. As found in other research, the use of inclusive language and a professional understanding of LGBTQI+ parenting issues are crucial for fostering positive parental engagement (Philippopoulos 2023).

Findings highlight that fathers and non-birth parents actively desire engagement with healthcare practitioners to address their mental health and well-being needs. Common challenges to improving father engagement include the predominance of a female healthcare workforce and healthcare practitioners’ lack of confidence in interacting with fathers (Humphries and Nolan 2015; Lovett et al. 2017).

The research in this review found that female health professionals working in this sector reported feeling ill-equipped to work with men. Healthcare professionals could benefit from interventions aimed at increasing their perceived self-efficacy in working with men (de Montigny et al. 2020). A focus on acquiring new knowledge, forming and adopting beliefs, and integrating these elements into the professional practices of healthcare practitioners may improve father- and non-birth parent-inclusive practice (Carryer et al. 2015).

During pregnancy and early parenthood, parents are often responsive to health promotion efforts because the well-being and development of the fetus, infant, and child can be powerful motivators for adopting a healthier lifestyle (Edvardsson et al. 2011). Interventions aimed at involving fathers or non-birthing parents should be designed, targeted, and implemented to also safeguard the well-being of women and children, for example, where there is family violence in the home (Comrie-Thomson et al. 2021).

Fathers impact child developmental outcomes, including children’s language and cognitive skills, better self-regulation, and fewer behavioural problems over time (Gonzalez et al. 2023). Father involvement benefits not only the mothers, newborns, and parents but may also foster stronger family relationships and promote bonding between the child and the non-birth parent (Cabrera et al. 2018). Fathers who take the time to support and affectionately care for their children positively impact their children’s development, and this has been found to be true even when controlling for maternal involvement (Ramchandani et al. 2013).

Our review identifies facilitators of more inclusive practice, such as explicit engagement with fathers and non-birth parents, including program redesign, facilitating connection with other fathers and non-birth parents, and for fathers specifically, a focused attention on men’s health and well-being. This is consistent with other research on inclusive nursing practice (Carryer et al. 2015; Marjadi et al. 2023). Being aware of assumptions and stereotypes, using inclusive language, and self-educating on diversity in all its forms are some of the key messages in contemporary research on inclusivity (Marjadi et al. 2023).

As evidenced by our systematic review, there has been little research on the experiences of same-sex non-birth parents, highlighting the need for further study. This gap in the literature suggests that more studies are necessary to understand the unique challenges faced by this group of parents. Such research could inform inclusive practices and policies to better support same-sex non-birth parents in their parenting roles, contributing to enhanced well-being for their families.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Systematic searching and data analysis techniques facilitated a high-quality meta-synthesis, yielding valuable and insightful outcomes. The decision to exclude papers from low- or middle-income countries means we might have overlooked valuable research. However, incorporating these papers could have posed challenges in synthesising the findings due to variations in nursing care models and diverse practice contexts.

Conclusion

Father- and non-birth parent-inclusive practice promotes the health and well-being of children and families. Recognising and addressing the unique needs and roles of fathers and non-birth parents ensures they are actively engaged and supported in parenting. Inclusive practices can enhance family dynamics, improve child development outcomes, and provide a more equitable and supportive environment for all family members.

Inclusive practice for fathers and non-birth parents entails developing environments, policies, and programs that actively involve and support fathers in all aspects of parenting and family life. Strategies include systematic outreach to fathers, adjusting the timing of visits, hiring fatherhood coordinators, customising activities to fathers’ preferences, and addressing their needs. Inclusive language and professional knowledge about LGBTQI+ parenting issues are key factors for positive parental empowerment.

Many experiences of child and family health services left lesbian non-birth mothers feeling insignificant and marginalised. Including lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender families in planning, developing, evaluating, and accessing early parenting services will promote acceptance of diversity and improve inclusive practice.

Programs need to consider what strategies are effective in engaging fathers, such as building relationships with fathers independent of their relationship with mothers, offering a range of services, setting goals with fathers, and helping families define their co-parenting roles and expectations (Stargel et al. 2020). More research is required to identify best-practice strategies for engaging fathers in home visits by nurses and other healthcare professionals (McGinnis et al. 2019).

Lastly, it is important to acknowledge that fathers want support from healthcare professionals. However, these professionals need to feel positive and confident about engaging with fathers, and this is likely to come from improved education and training to help them address their lack of confidence (Humphries and Nolan 2015).

Data availability

The data that support this study are available in the article, the references sited, and the accompanying online Supplementary material.

Declaration of funding

This systematic review is part of a larger study funded by a seeding grant for early to mid-career researchers funded by La Trobe University School of Nursing and Midwifery. The funding body had no role in the preparation of the data or manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

Adams C, Hooker L, Taft A (2021) Threads of practice: enhanced maternal and child health nurses working with women experiencing family violence. Global Qualitative Nursing Research 8,.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Allport BS, Johnson S, Aqil A, Labrique AB, Nelson T, Kc A, Carabas Y, Marcell AV (2018) Promoting father involvement for child and family health. Academic Pediatrics 18, 746-753.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Baldwin S, Malone M, Murrells T, Sandall J, Bick D (2021) A mixed-methods feasibility study of an intervention to improve men’s mental health and wellbeing during their transition to fatherhood. BMC Public Health 21, 1813.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bennett E, Berry K, Emeto TI, Burmeister OK, Young J, Shields L (2017) Attitudes to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender parents seeking health care for their children in two early parenting services in Australia. Journal of Clinical Nursing 26, 1021-1030.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Boykin A, Miller E, Garfield CF, Jones KA (2022) Pediatric provider practices in engaging young fathers at pediatric visits. Pediatric Nursing 48, 278-282.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cabrera NJ (2020) Father involvement, father-child relationship, and attachment in the early years. Attachment & Human Development 22, 134-138.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Cabrera NJ, Volling BL, Barr R (2018) Fathers are parents, too! Widening the lens on parenting for children’s development. Child Development Perspectives 12, 152-157.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Campbell S, McCalman J, Redman-MacLaren M, Canuto K, Vine K, Sewter J, McDonald M (2018) Implementing the Baby One Program: a qualitative evaluation of family-centred child health promotion in remote Australian Aboriginal communities. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 18, 73.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cardenas SI, Morris AR, Marshall N, Aviv EC, Martínez García M, Sellery P, Saxbe DE (2022) Fathers matter from the start: the role of expectant fathers in child development. Child Development Perspectives 16, 54-59.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Carlson J, Edleson JL, Kimball E (2014) First-time fathers’ experiences of and desires for formal support: a multiple lens perspective. Fathering 12, 242-261.

| Google Scholar |

Carryer J, Halcomb E, Davidson PM (2015) Nursing: the answer to the primary health care dilemma. Collegian 22, 151-152.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Clifford-Motopi A, Fisher I, Kildea S, Hickey S, Roe Y, Kruske S (2022) Hearing from First Nations Dads: qualitative yarns informing service planning and practice in urban Australia. Family Relations 71, 1933-1948.

| Google Scholar |

Comrie-Thomson L, Gopal P, Eddy K, Baguiya A, Gerlach N, Sauvé C, Portela A (2021) How do women, men, and health providers perceive interventions to influence men’s engagement in maternal and newborn health? A qualitative evidence synthesis. Social Science & Medicine 291, 114475.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cooke D, Bennett E, Simpson W, Read K, Kendall G (2019) Father inclusive practice in a parenting and early childhood organisation: the development and analysis of a staff survey. Australian Journal of Child and Family Health Nursing 16, 3-10.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cooklin AR, Giallo R, Strazdins L, Martin A, Leach LS, Nicholson JM (2015) What matters for working fathers? Job characteristics, work-family conflict and enrichment, and fathers’ postpartum mental health in an Australian cohort. Social Science & Medicine 146, 214-222.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Cui C, Li M, Yang Y, Liu C, Cao P, Wang L (2020) The effects of paternal perinatal depression on socioemotional and behavioral development of children: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Psychiatry Research 284, 112775.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

de Montigny F, Gervais C, Meunier S, Dubeau D (2017) Professionals’ positive perceptions of fathers are associated with more favourable attitudes towards including them in family interventions. Acta Paediatrica 106, 1945-1951.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

de Montigny F, Gervais C, Larivière-Bastien D, Dubeau D (2020) Assessing the impacts of an interdisciplinary programme supporting father involvement on professionals’ practices with fathers: a qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing 29, 1003-1016.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Diniz E, Brandão T, Monteiro L, Veríssimo M (2021) Father involvement during early childhood: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Family Theory & Review 13, 77-99.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Edvardsson K, Ivarsson A, Eurenius E, Garvare R, Nyström ME, Small R, Mogren I (2011) Giving offspring a healthy start: parents’ experiences of health promotion and lifestyle change during pregnancy and early parenthood. BMC Public Health 11, 936.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Engström HA, Häggström-Nordin E, Borneskog C, Almqvist AL (2019) Mothers in same-sex relationships-Striving for equal parenthood: a grounded theory study. Journal of Clinical Nursing 28, 3700-3709.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ferguson H, Gates P (2015) Early intervention and holistic, relationship-based practice with fathers: evidence from the work of the Family Nurse Partnership. Child & Family Social Work 20, 96-105.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fisher J, Rowe H, Wynter K, Tran T, Lorgelly P, Amir LH, Proimos J, Ranasinha S, Hiscock H, Bayer J, Cann W (2016) Gender-informed, psychoeducational programme for couples to prevent postnatal common mental disorders among primiparous women: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 6, e009396.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Forbes F, Wynter K, Zeleke BM, Fisher J (2021) Fathers’ involvement in perinatal healthcare in Australia: experiences and reflections of Ethiopian-Australian men and women. BMC Health Services Research 21, 1029.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Forbes F, Wynter K, Zeleke BM, Fisher J (2023) Engaging culturally diverse fathers in maternal and family healthcare: experiences and perspectives of healthcare professionals. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 34, 691-701.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Gold S, Edin KJ, Nelson TJ (2020) Does time with dad in childhood pay off in adolescence? Journal of Marriage and Family 82, 1587-1605.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Gonzalez JC, Klein CC, Barnett ML, Schatz NK, Garoosi T, Chacko A, Fabiano GA (2023) Intervention and implementation characteristics to enhance father engagement: a systematic review of parenting interventions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 26, 445-458.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Gruson-Wood J, Haines J, Rice C, Chapman GE (2023) The problem of heteronormativity in family-based health promotion: centring gender transformation in Ontario, Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health 114, 659-670.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Guterman NB, Bellamy JL, Banman A (2018) Promoting father involvement in early home visiting services for vulnerable families: findings from a pilot study of “Dads matter”. Child Abuse & Neglect 76, 261 272.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Harrison R, Jones B, Gardner P, Lawton R (2021) Quality assessment with diverse studies (QuADS): an appraisal tool for methodological and reporting quality in systematic reviews of mixed- or multi-method studies. BMC Health Services Research 21, 144.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hjalmhult E, Glavin K, Okland T, Tveiten S (2014) Parental groups during the child’s first year: an interview study of parents’ experiences. Journal of Clinical Nursing 23, 2980-2989.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hrybanova Y, Ekström A, Thorstensson S (2019) First-time fathers’ experiences of professional support from child health nurses. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 33, 921-930.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Humphries H, Nolan M (2015) Evaluation of a brief intervention to assist health visitors and community practitioners to engage with fathers as part of the healthy child initiative. Primary Health Care Research & Development 16, 367-376.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kelsall-Knight L, Sudron C (2020) Non-biological lesbian mothers’ experiences of accessing healthcare for their children. Nursing Children and Young People 32, 38-42.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kerppola J, Halme N, Marja-Leena P, Anna MP (2019) Parental empowerment—Lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans or queer parents’ perceptions of maternity and child healthcare. International Journal of Nursing Practice 25, e12755.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kroll ME, Carson C, Redshaw M, Quigley MA (2016) Early father involvement and subsequent child behaviour at ages 3, 5 and 7 years: prospective analysis of the UK Millennium Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 11, e0162339.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Laffar K, Elliott H (2021) Influences that affect health visitors’ ability to work with fathers who are perpetrators of domestic abuse. Journal of Health Visiting 9, 246-251.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lovett D, Rasmussen B, Holden C, Livingston PM (2017) Are nurses meeting the needs of men in primary care? Australian Journal of Primary Health 23, 319-322.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Machin AJ (2015) Mind the gap: The expectation and reality of involved fatherhood. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, and Practice about Men as Fathers 13, 36-59.

| Google Scholar |

Marjadi B, Flavel J, Baker K, Glenister K, Morns M, Triantafyllou M, Strauss P, Wolff B, Procter AM, Mengesha Z, Walsberger S, Qiao X, Gardiner PA (2023) Twelve tips for inclusive practice in healthcare settings. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, 4657.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mcginnis S, Lee E, Kirkland K, Smith C, Miranda-Julian C, Greene R (2019) Engaging at-risk fathers in home visiting services: effects on program retention and father involvement. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal 36, 189-200.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Osborne C, DeAnda J, Benson K (2022) Engaging fathers: expanding the scope of evidence-based home visiting programs. Family Relations 71, 1159-1174.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Page MJ, Mckenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, Mcdonald S, Mcguinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372, 1-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Parry YK, Ankers MD, Abbott S, Willis L, Thorpe L, O’Brien T, Richards C (2019) Antenatal dads and first year families program: a qualitative study of fathers’ and program facilitators’ experiences of a community-based program in Australia. Primary Health Care Research & Development 20, e154.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pearson A, White H, Bath-Hextall F, Salmond S, Apostolo J, Kirkpatrick P (2015) A mixed-methods approach to systematic reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation 13, 121-131.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Philippopoulos E (2023) More than just pronouns – gender-neutral and inclusive language in patient education materials: suggestions for patient education librarians. Journal of the Medical Library Association 111, 734-739.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Ramchandani PG, Domoney J, Sethna V, Psychogiou L, Vlachos H, Murray L (2013) Do early father–infant interactions predict the onset of externalising behaviours in young children? Findings from a longitudinal cohort study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 54, 56-64.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Riggs E, Yelland J, Szwarc J, Wahidi S, Casey S, Chesters D, Fouladi F, Duell-Piening P, Giallo R, Brown S (2016) Fatherhood in a new country: a qualitative study exploring the experiences of Afghan men and implications for health services. Birth 43, 86-92.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Rollans M, Kohlhoff J, Meade T, Kemp L, Schmied V (2016) Partner involvement: negotiating the presence of partners in psychosocial assessment as conducted by midwives and child and family health nurses. Infant Mental Health Journal 37, 302-312.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Rominov H, Giallo R, Pilkington PD, Whelan TA (2018) “Getting help for yourself is a way of helping your baby:” Fathers’ experiences of support for mental health and parenting in the perinatal period. Psychology of Men & Masculinity 19, 457-468.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ross NJ, Church S, Hill M, Seaman P, Roberts T (2012) The perspectives of young men and their teenage partners on maternity and health services during pregnancy and early parenthood. Children & Society 26, 304-315.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sherriff N, Panton C, Hall V (2014) A new model of father support to promote breastfeeding. Community Practitioner 87, 20-24.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

Shorey S, Dennis C-L, Bridge S, Chong YS, Holroyd E, He H-G (2017) First-time fathers’ postnatal experiences and support needs: a descriptive qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing 73, 2987-2996.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Stargel LE, Fauth RC, Goldberg JL, Ann EM (2020) Maternal engagement in a home visiting program as a function of fathers’ formal and informal participation. Prevention Science 21, 477-486.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Thomas J, Harden A (2008) Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 8, 45.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wells MB, Varga G, Kerstis B, Sarkadi A (2013) Swedish child health nurses’ views of early father involvement: a qualitative study. Acta Paediatrica 102, 755-761.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wells MB, Kerstis B, Andersson E (2021) Impacted family equality, self-confidence and loneliness: a cross-sectional study of first-time and multi-time fathers’ satisfaction with prenatal and postnatal father groups in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 35, 844-852.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |