Considerations in the development of an mHealth approach to increase cervical screening participation in primary care in Victoria, Australia

Claire Zammit A * , Maleeha Ashfaq A , Lucy Boyd A , Caitlin Paton A , Joyce Jiang B C , Julia Brotherton A Claire Nightingale A

A * , Maleeha Ashfaq A , Lucy Boyd A , Caitlin Paton A , Joyce Jiang B C , Julia Brotherton A Claire Nightingale A

A

B

C

Abstract

Short message service (SMS) messages are an effective means of delivering health interventions, including promoting cancer screening. SMS offers opportunities to remind people about cervical screening and promote the self-collection option available in Australia’s National Cervical Screening Program. This research aimed to explore the acceptability of SMS reminders sent by general practices to eligible patients promoting the option of self-collection for cervical screening.

We conducted a cross-sectional survey (n = 221) with women and people with a cervix, and focus group discussions (n = 5) with women aged ≥50 years (n = 7), regional/rural residents (n = 6) and bicultural health educators (n = 10) in Victoria, Australia. We examined awareness of self-collection, current receipt and acceptability of health promotion SMSs, and preferences for SMS content promoting cervical screening.

Most survey respondents (83%) found SMS reminders for cervical screening acceptable, stating a preference for their first name (71%) and clinic’s name (58%) to be included. Focus group participants had varying awareness of self-collection, with concerns about accuracy, sample collection and accessibility. Clear communication about clinician- and self- collection options was considered crucial. Most participants were hesitant to click embedded links. SMS acceptability may be affected by limited knowledge of self-collection, accessibility for people with disabilities, differing English or digital literacy, and privacy concerns.

SMS messages appear to be an appropriate way to raise awareness about the choice of self-collection, but SMS may not be suitable as a population-based strategy. Leveraging general practitioner endorsement through SMS may improve participation, particularly for people who may prefer self-collection, but are unaware of this option

Keywords: acceptability, cervical screening, general practice, mHealth, primary health, self-collection, self-sampling, text-messaging (SMS) reminders.

Introduction

Text messaging, or short message services (SMS), have become a standard tool in healthcare communication and are effective delivery methods for health interventions, including improving cancer screening participation in primary health care internationally and in Australia (Liu et al. 2024; McIntosh et al. 2024). The recent SMARTScreen trial demonstrated a 16.5% increase in National Bowel Screening Program participation through general practice-endorsed SMS messages (McIntosh et al. 2024), with systematic review evidence suggesting a 41% increase for cervical screening participation with SMS alone (RR 1.41, 95% CI: 1.14–1.73; Liu et al. 2024) Similarly, a Cochrane review revealed that cervical screening uptake was significantly higher among those who received an SMS invitation compared with standard care (RR 2.24, 95% CI: 1.67–3.00; Staley et al. 2021). However, considering the equity implications of SMS-based strategies within Australia’s cancer screening programs is crucial, particularly for under-screened priority populations with diverse needs and experiences.

Under-screened priority populations may have varying levels of digital or mobile accessibility. For cervical screening, populations more likely to be under-screened include Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples, culturally and linguistically diverse people, people who are LGBTQIA+ and people who are intersex, people living in regional or remotes areas, or people with an intellectual or physical disability (Australian Centre for the Prevention of Cervical Cancer 2023). The Australian Digital Inclusion Index checks how well people can access, use and afford digital technologies (Thomas et al. 2023). In 2022, the index highlighted that people with a disability (24.5%), those residing in public housing (28.2%), those who have not completed secondary school (32.5%) or those who are aged ≥75 years (42.3%) experience higher levels of digital exclusion (index score of <45; Thomas et al. 2023). Furthermore, a recent qualitative systematic review highlights barriers and facilitators that culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) populations experienced with using digital health interventions, including those that are SMS based (Whitehead et al. 2023). Common facilitators of these technologies included culturally centred, modernised approaches that promote healthcare access through accurate information. The maintenance of privacy and a strong connection with healthcare providers was also paramount (Whitehead et al. 2023), particularly when it comes to cervical screening.

Australia has successful and longstanding national programs for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination and cervical screening, and is on track to reach the World Health Organization’s elimination target for cervical cancer (<4 cases per 100,000) by 2035 (Australian Centre for the Prevention of Cervical Cancer 2023; Brotherton et al. 2024). Achieving equity in elimination is far from assured, however, as there are many populations, including people from CALD communities, people living rurally and/or in lower socioeconomic areas, people living with physical or intellectual disability, and gender-diverse or trans people who continue to experience greater barriers to screening participation and are therefore less likely to screen (Allen-Leigh et al. 2017; Azar et al. 2022; Chandrakumar et al. 2022; Power et al. 2022, 2024; Amos et al. 2024; Fullerton et al. 2024; Welsh et al. 2024). To promote equitable access to screening, self-collection cervical screening (where a person can collect their own vaginal sample for HPV testing) was introduced during the National Cervical Screening Program’s (NCSP) transition from cytology- to HPV-based screening in December 2017. Strong evidence demonstrates self-collection is a safe, accurate, acceptable and effective method of cervical screening, and that it can increase screening participation for many populations, including those that are under-screened (Arbyn et al. 2018; Yeh et al. 2019; Serrano et al. 2022).

All screening participants now have a choice between clinician-collected and self-collected options for cervical screening in the Australian NCSP. Most screening (including self-collection) is conducted within a primary healthcare consultation by a GP (Cancer Council Australia 2022). This model of care ensures that screening participants are connected to a healthcare practitioner to support any potential follow up. However, it also means that participants are largely reliant on practitioners to inform them of their available screening options, which may present a barrier to accessing self-collection, given that recent research in Australia indicates that there is still varying awareness, support and adoption of self-collection among practitioners, in addition to low awareness among the eligible population (Matthew-Maich et al. 2016; Gertig and Lee 2023).

There is evidence to demonstrate that healthcare provider-endorsement is an effective strategy to increase screening uptake in cancer screening programs (McIntosh et al. 2024; Verbunt et al. 2024). Population-level screening registers can also play an important role in supporting providers and eligible participants by sending invitations and acting as a safety net for participants who may be less connected to a provider choice (Gertig and Lee 2023). The National Cancer Screening Register (NCSR) supports the NCSP by sending eligible participants invitation and reminder letters, providing information about both screening options available (Gertig and Lee 2023). Many general practices operate their own reminder and recall systems for their active patients, often through a mailed letter (Verbunt et al. 2024). As these reminders depend upon the accuracy of the data about screening held at the practice, the recent integration of the NCSR into most practice software systems will better enable providers to confirm patients’ screening history date (Gertig and Lee 2023; Verbunt et al. 2024). Many tools now exist to facilitate SMS, rather than letter-based invitations, creating new opportunities for practices to promote cervical screening, including self-collection. Australia’s National Strategy for the Elimination of Cervical Cancer recommends to ‘trial and utilise technology to support digital invitations, reminders, and navigation to follow up activities for people with screening results that require further investigation’ (Australian Centre for the Prevention of Cervical Cancer 2023). Therefore, this study aimed to explore the acceptability of a general practice-sent, SMS-based invitation for cervical screening in the context of self-collection being an available choice for routine screening.

Methods

Study design

Our study used a mixed methods approach, including a cross-sectional survey to explore the prospective acceptability and specific content of an SMS among women and people with a cervix from the general Victorian population. Focus group discussions (FGD) designed to gain specific insights from women and people with a cervix aged ≥50 years, living regionally/rurally, and who were from CALD communities were conducted. These groups were included, given that they experience additional barriers to participating in cervical screening, as well as differing acceptability of an SMS-based mHealth approach (Matthew-Maich et al. 2016; Azar et al. 2022; Power et al. 2022; Whitehead et al. 2023).

Survey of eligible Victorian population

We used a flexible approach to survey recruitment to ensure a diverse, representative sample. Participants were eligible for the survey if they reported having a cervix, were aged between 25 and 75 years, and resided in Victoria. Australian-based social media advertisements (specifically through Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn or Twitter) through collaborating accounts were the main methods of recruitment. Informed consent was provided by way of answering the question ‘do you agree to start and participate in the survey? – yes/no’. An embedded link to a copy of the plain language statement for the survey was made available within the preamble of the survey. Once the survey was complete, participants were invited to leave their contact details if they were interested in participating in FGDs. Survey participants had the option to enter a raffle to win one of four A$100 eGift card vouchers as an incentive to participate. Once the survey closed, a random number generated mapped to participants’ survey ID randomly allocated the vouchers to recipients who were notified and sent vouchers via email.

The survey instrument was developed based on a comprehensive review of the literature, and in consultation with research team members, collaborator organisations, and a community and consumer advisory panel (CCAP). The CCAP panel comprised members of priority groups facing screening barriers (women with a physical disability, LGBTQIA+ and people with a cervix, women living rurally/remotely, women aged ≥50 years, or from a culturally diverse background or ethnicity). CCAP members reviewed the survey, including a series of mock SMSs, and provided feedback that was adopted to enhance the survey’s look, feel and relevance. This included rewording the survey preamble, survey questions and mock SMSs to make them easier to understand.

Mock SMSs were developed based on previous research and informed by the health belief model (Champion and Skinner 2008; Machado Colling et al. 2024; Temminghoff et al. 2024; Table 1). Survey domains included demographic information, cervical screening history, current SMS practices in relation to primary care and SMS implementation considerations, including preferred receipt time of day, sender preferences, acceptability of including hyperlinks, as well as Likert ratings of the mock SMSs (Fig. 1).

| Health belief model construct (Champion and Skinner 2008) | Operationalised based on existing research (Machado Colling et al. 2024; Temminghoff et al. 2024) | Mock SMS drafts after team and CCAP review included in survey | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived susceptibility | People understand the risks of delaying cervical screening and early detection | Dear Alex, most cases of cervical cancer occur in people who don’t have their screening test. Did you know you may be eligible to collect your own sample? Call Smith St Medical Clinic to find out more. | |

| Perceived severity | People understand the risks of developing cervical cancer, which could be life threatening | Dear Alex, you are due for your cervical screening test. You may be eligible to collect your own sample if you choose, which could save your life. It’s easy, accurate and private. Call Smith St Medical Clinic to find out more. | |

| Perceived self-efficacy | People understand their abilities to complete and participation in cervical screening through both options i.e. self- and practitioner-collected | Dear Alex, your cervical screening test is due and Smith St Medical Clinic offers self-collection; a quick, easy, private and reliable option that you can do yourself. Call Smith St Medical Clinic to find out more. | |

| Perceived barriers | People understand the barriers to cervical screening i.e. invasive procedure, time-poor, painful that are addressed through self-collection | Dear Alex, your cervical screening test is due. You may be eligible to collect your own sample, which may be more comfortable. It’s quick, easy, reliable and private. Call Smith St Medical Clinic to find out more. | |

| Perceived benefits | People understand the benefits of early detection through cervical screening and/or benefits of self-collection i.e. its quick, easy and private | ||

| – | – Information, requires a click through | Your doctor from Smith St Medical Clinic has sent you some information about the National Cervical Screening Program. Click here for more info https://www.health.gov.au/campaigns/self-collection-for-the-cervical-screening-test or call us on 03 9862 5887 if you have any questions. |

Examples of mock SMSs provided through the online cross-sectional survey and within focus group discussions.

The survey was housed on Qualtrics (Provo) to minimise the risk of fraudulent responses using in built features, such as ballot box stuffing prevention, Google reCAPTCHA scores, security scan monitoring and RelevantID metadata collection (including browser location, duplicate IDs, hidden duplicate and fraud score fields) embedded into the survey’s flow.

Survey data collection occurred on 1–29 May 2023. Quantitative descriptive analysis was used to characterise variables through crude frequencies and percentages. All analyses were completed on Stata 18 software (StataCorp).

Focus group discussion with representatives from priority populations

FGD participants were recruited in two ways. First, contact details of those who expressed interest through the survey were exported and stratified based on specific demographic data. Postcodes were mapped to the Modified Monash Model Suburb and Locality Classification with postcodes in MM3 (large rural towns) to MM7 (very remote communities). Details of survey participants in these postcodes or indicating age ≥50 years were included within an initial sampling frame. Second, bicultural health educators employed by our partner organisation were directly invited to participate. These educators, each with experience providing cancer screening education to their communities, had knowledge regarding the informational needs and acceptability of mHealth interventions within their communities. All FGD participants were provided with plain language statements in English and a consent form prior to participation. FGD participants received A$65 for their participation as consumers, and bicultural health educators received A$150 as remuneration to recognise the time they took out of paid work hours to participate.

Themes covered in the FGDs included awareness and acceptability of self-collection and the acceptability of mHealth approaches for health promotion. Participants were asked to review the preferred mock SMSs identified in Phase 1, and to consider SMS attributes, such as greetings, sender preference, informational needs and the inclusion of hyperlinks.

The FGD guide was piloted twice within the broader research team before active data collection to ensure adequate flow of questions, and appropriate sentence and plain language structure. All FGDs were facilitated in English by authors CP, CZ and CN over Microsoft Teams, audio recorded, and transcribed verbatim using Otter.AI transcription services. Deductive thematic analysis was used to analyse FGDs using an a priori coding framework informed by the theoretical framework of acceptability, which explores the theoretical underpinnings of a health interventions’ prospective or retrospective acceptability to a population (Sekhon et al. 2017).

After reviewing the data, an inductive approach identified emergent codes within the broader level themes of the theoretical framework of acceptability, ensuring accurate and thorough coding. Author CZ initially coded the data, which author MA cross-coded to ensure the framework’s accuracy. Authors CZ, MA and CN extensively discussed the final analysis until they reached a consensus on data interpretation. Open-ended survey responses were also analysed using the same framework. All qualitative data from both study phases was organised and analysed using Lumivero NVivo (version 14).

Results

Demographics

Of 264 respondents who started the survey, 43 (16.3%) responses were excluded due to incomplete consent or ineligibility (i.e. did not reside in Victoria, did not have a cervix), missing contact details or high reCAPTCHA scores. A total of 221 respondents were included in the final analysis. Most participants identified as female (93%), were aged between 25 and 74 years, were Australian born (78%), lived in metropolitan areas (i.e. MM1; 72%), and were non-Indigenous (97%). Most participants had completed cervical screening at least once (85%). Of the respondents that reported their screening status (n = 163), 88% reported being up to date with cervical screening and 12% reported being overdue or could not recall their last screening episode. Most respondents (77%) reported knowing that self-collection was available.

Over half of survey respondents (58%, n = 129) expressed interest in participating in the FGDs. Participants living in regional or rural Victoria (n = 6) were aged ≥50 years (50%, n = 3) and <50 years (50%, n = 3), respectively.

We contacted 49 potential participants, with 10 providing informed consent and taking part in a FGD (Table 2). All 10 bicultural health educators directly invited to participate consented to take part in an FGD. Culturally and linguistically diverase communities represented by bicultural health educators included Filipino, Chinese Mandarin, Karen, Vietnamese, Hindi/Punjabi, Dari and Arabic speaking communities. FGDs (n = 5) went from between 37 and 86 min (average 73 min).

| Demographic | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Survey participants | N = 221 | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 25–29 | 42 (19%) | |

| 30–35 | 40 (18%) | |

| 35–39 | 34 (15%) | |

| 40–49 | 58 (26%) | |

| 50–59 | 33 (15%) | |

| ≥60 | 14 (6%) | |

| Indigenous status | ||

| Aboriginal | 5 (2%) | |

| Non-Indigenous | 214 (97%) | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (1%) | |

| Geography (MM classification) | ||

| Metropolitan (MM1) | 176 (80%) | |

| Regional (MM2) | 15 (7%) | |

| Large to small rural towns (MM3–5) | 28 (13%) | |

| Missing | 2 (<1%) | |

| Country of birth | ||

| Australia | 172 (78%) | |

| Aotearoa New Zealand | 8 (4%) | |

| Europe and UK | 14 (6%) | |

| North and South America | 8 (4%) | |

| East Asia | 4 (2%) | |

| South and Southeast Asia | 11 (5%) | |

| East and South Africa | 2 (1%) | |

| Middle Eastern | 2 (1%) | |

| Sex or gender | ||

| Female | 206 (93%) | |

| Non-binary/third gender | 10 (5%) | |

| Transgender | 2 (1%) | |

| Other | 3 (1%) | |

| Ever had a cervical screening | ||

| No | 34 (15%) | |

| Yes | 187 (85%) | |

| Last cervical screening | ||

| <2 years | 52 (24%) | |

| 2–5 years | 92 (41%) | |

| 6–10 years | 8 (4%) | |

| >10 years | 8 (4%) | |

| I don’t remember | 3 (1%) | |

| Did not answer | 58 (26%) | |

| Awareness of self-collection before survey | ||

| No | 51 (23%) | |

| Yes | 170 (77%) | |

| Focus group participants | N = 10 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <50 years | 3 (30%) | |

| ≥50 years | 7 (70%) | |

| Geography | ||

| Metropolitan (MM1) | 4 (40%) | |

| Regional or Rural (MM2–MM5) | 6 (60%) | |

| Country of birth | ||

| Australia | 7 (70%) | |

| North America, Europe and United Kingdom | 3 (30%) | |

Knowledge, awareness and acceptability of self-collection

Most survey respondents (77%) were aware of the option of self-collection prior to completing the survey (Table 1). The most common ways of becoming aware of self-collection were through news and social media or through their primary care provider. However, among FGD participants, there was mixed awareness of the availability of self-collection for routine screening.

Instagram over a year ago, a post about self-collection being made an option for everyone made me book an appointment with my Dr to do this (Survey participant, age 25–29 years, Metro)

‘…before this research, I was unaware. And I also work in healthcare… I’m a bit surprised.’ (FGD participant, age >50 years, Rural)

Focus group participants discussed concerns about the accuracy of self-collection compared with a clinician-collected cervical screen. People also discussed that needing to go to the GP would remain a barrier to screening, even with the self-collection option available.

To go to GP, they have to queue up and have to, like call make an appointment or something. That’s what the concern (FGD participant, DV Bicultural Health Educator)

Acceptability of SMS approach

Most survey participants (63%) reported already receiving SMSs from their general practice. These SMSs were mainly reminding people of booked appointments (96%), for test results (38%) or reminders for other things to do at the practice (33%), including receiving SMSs as reminders to complete cervical screening (20%; Table 3). Most respondents (82%) indicated that they would like to receive an SMS as a reminder for cervical screening from their doctor or clinic. Similarly, FGD participants reported already receiving SMSs from their general practices for booked appointments, test results or vaccinations, and viewed these as effective reminder methods. In general, most people were supportive of using SMS as an approach to promote participation in cervical screening.

But I get reminders for my appointments. I get the texts [to] inform me that the test results for the ROI [release of information]. But clearly, I don’t get the results in that text and might tell me that I need to ‘contact Dr’ or ‘no need to contact Dr’. Like it’s really, it’s all good. (FGD participant, age 30–49 years, Rural)

| N = 221 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Receive SMS from general practice A | ||

| No | 82 (37%) | |

| Yes | 138 (63%) | |

| Reminder for booked appointments B | 133 (96%) | |

| Test results B | 53 (38%) | |

| Reminders to do things B | 46 (33%) | |

| Receiving SMS reminders for screening B | 44 (20%) | |

| Acceptability of SMS approach C | ||

| I would like to receive an SMS | 177 (82%) | |

| I would not like to receive an SMS | 10 (5%) | |

| I am indifferent to receiving an SMS | 29 (13%) | |

| Specific reminder vs general information D | ||

| Cervical scree reminder | 196 (97%) | |

| General Information | 6 (3%) | |

| Preferred timing of SMS approach E | ||

| <10 am | 17 (8%) | |

| 10 am−5 pm | 65 (32%) | |

| >5 pm | 13 (6%) | |

| No preference | 110 (54%) | |

| Name included E | ||

| First name only | 145 (71%) | |

| Full name | 32 (16%) | |

| No name | 28 (14%) | |

| Preferred sender | ||

| Name of clinic E | 119 (58%) | |

| Name of clinic and GP E | 85 (41%) | |

| Yours and GP’s name E | 81 (40%) | |

| Government E | 53 (26%) | |

| NCSR E | 138 (67%) | |

| Cancer Council Victoria logo E | 59 (29%) | |

| Key actions prompted F | ||

| Read the message on one screen | 137 (62%) | |

| Click to make an appointment online | 165 (75%) | |

| Click a phone number link to call immediately | 107 (48%) | |

| Click a link to extra information/resources | 89 (40%) | |

Considerations for SMS message content and usability

Almost three-quarters of survey respondents indicated that they would like their first name (71%) or their full name (16%) included in the message.

Over half of survey participants (67%) indicated that they would be more likely to pay attention to the SMS if it came from the NCSR or if it included the name of their clinic (58%). Only one-quarter (26%) would be likely to pay attention if it came from the Government. FGDs results indicated the same preference for including their first name; however, there was a strong preference among most that the message comes from their doctor.

Yeah, I agree with that. I think maybe I think I’d like it to have my first name and then identify the clinic. (FGD participant, age 30–49 years, Regional)

I think this is really simple. It’s coming from the doctor. They would trust their doctor more than the cancer registry or the Cancer Council, I guess. It’s more personal rather than a body saying [to] them’ Click clinic to find out more.’ No, it’s just ‘Call the clinic to book.’ Be precise. (FGD participant, GH Bicultural Health Educator)

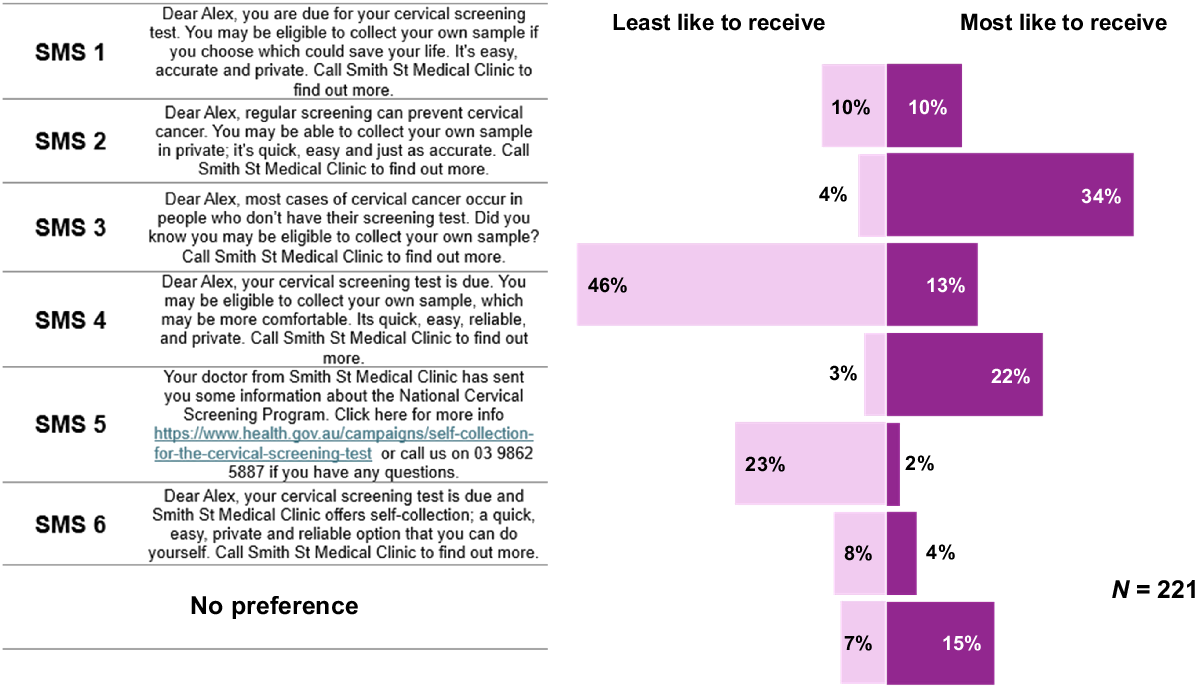

Among the survey respondents who would like to receive a message about cervical screening, the majority (97%) wanted the message to specifically remind them that they were due for screening, rather than conveying generic information. Of six draft messages presented in the survey, participants chose a single option they would most or least like to receive (Fig. 2). SMS 6 was the most frequently reported as the ‘most like to receive’, with approximately one-third of participants (34%, n = 75) choosing this. SMS 4 was the most frequently reported as the ‘least like to receive’, with almost half of the survey respondents choosing this (46%, n = 102), although there was no clear majority consensus on which was most liked (Fig. 2).

Crude percentages of which mock SMSs of six presented that survey participants would most like or least like to receive for cervical screening.

Information contained within the message was discussed further in the FGDs, with some participants indicating they wanted a stronger call for action and emphasis on the importance of screening. Participants in FGDs appreciated that choice of screening options was still available, recognising not everyone would prefer or know about self-collection. FGD participants suggested keeping the message about its availability simple and concise to avoid confusion.

I would prefer if we can add something about the importance of the screening, for example, remember, screening saves a lot of lives. Just as simple as this. (FGD participant, HA Bicultural Health Educator)

We know that self-screening is an option, but if someone just gets this cold turkey, will they understand that they can have the previous option? Or think, oh, no, I’ve got to do it myself now. Should that be included? That that’s an option? (FGD participant, age 50–74 years, Metro)

Most survey respondents (75%) indicated that it was important to be able to ‘click to make an appointment online’, 62% indicated being able to ‘read the SMS on one screen’, and almost half (48%) wanted to be able to ‘click a phone number they could call to make an appointment’ and less important to be able to ‘click a hyperlink for more information’ (Table 3). Although 54% of survey respondents had no preferred time to receive the SMS (Table 3), FGD participants indicated the convenience of receiving it during business hours to facilitate booking an appointment.

Probably sometime during business hours, so that if you need that appointment, you can make it. It’s not in the middle of the night where you’re going to fall asleep or wake up in the morning going, ‘what’s this?’ (FGD participant, age 30–49 years, Rural)

Accessibility considerations

Participants across the survey and FGDs reflected on the need to avoid one-size-fits-all approaches, indicating that the SMS would not be suited to all members in the Victorian screening population. Specifically, SMSs in English could create additional barriers and inadvertent privacy concerns.

…many parents would use their children for translating or interpreting what’s in the text message, what’s in the email, but when it comes to womens’ health, it’s something that’s not appropriate. (FGD participant, MA Bicultural Health Educator)

So they were, they were saying ‘I received the bowel cancer toolkit. That’s why I did it. But as a participant who live here, like many, many years,’ she said, ‘I have never received any information about cervical screening. That’s why I haven’t done it.’ So just wondering, how could participant[s] actually get it [the reminder] if it’s like targeting every single person who need it?…’ (FDG participant, YC Bicultural Health Educator)

Wariness of scams

Despite the majority (72%) of survey respondents indicating that they would like to click on a hyperlink to obtain more information about cervical screening, there were also some concerns.

I didn’t realise until I saw the example with the link how much it would look like a scam. I’d avoid links at all costs. (Survey participant, age 50–59 years, Metro)

This was re-iterated in the focus group discussions, which revealed that people were hyper-aware of SMS-based scams, and most indicated that they would not be likely to click on a link within an SMS. There was also the perception that including a hyperlink could mean foregoing engagement with the SMS all together or that the approach would only be reaching people who are active patients at that general practice.

I probably wouldn’t. I just, it would be something else just to look at and I probably wouldn’t be that interested, after having done them before. (FDG participant, 30–49 years, Rural)

Conversely, some participants also received scams in their own language or did not trust in-language translations. In this scenario, this was also a perceived burden to participation in the approach.

If there is a link, a legitimate link, I would click if it looked okay to me. But if I go to that link, and there is Dari translation, I w[on’t] read it. Because… I don’t believe that translation much accurate, accurately. So whatever I do I interpret my own language. (MD participant, Bicultural Health Educator)

Discussion

Our study findings confirm that SMS is an acceptable form of communication from general practice to patients, and provides insights into how this approach can be optimised for invitations, recalls or reminders regarding routine cervical screening, including through self-collection. Participants in our study indicated that they would: (1) prefer SMSs to be addressed to them personally, (2) to specifically remind them that their screening test is due, (3) to come from their primary care provider, (4) to be short and concise, and (5) to ensure that the choice of screening methods is highlighted. Direct links to call and make an appointment were thought to be important, but there was substantial hesitation about clicking on any hyperlinks included. Our findings also suggest that the approach may not be suitable for everyone.

Almost one-quarter (23%) of survey participants were unaware of the option of self-collection for their cervical screening. Some FGD participants noted they became aware of self-collection from their involvement in this study and perceived that others within their social networks would be unaware of this option. This aligns with recent data reported from local and international settings regarding low awareness of self-collection (Zammit et al. 2022; Creagh et al. 2023; MacLaughlin et al. 2024). Knowing they could still opt for a clinician-collected cervical screening test was equally important, emphasising empowerment over their preference for screening modality. In 2024, 18 months after the choice became available and 14 months after data collection ceased for this study, national health promotion campaigns were launched aimed at raising awareness of the choice of screening method, particularly for priority populations. As described previously, the opportunity for eligible participants to access self-collection is dependent on general practitioners’ offer, with evidence suggesting some practitioners still harbour concerns surrounding self-collection’s accuracy and perceived loss of opportunity to perform a pelvic examination (Creagh et al. 2023, 2024). Therefore, the provision of choice in screening procedure through strategies that raise the awareness of, and trust in, both screening choices for participants and practitioners should be prioritised to promote equitable screening participation for everyone.

Concerns were raised by participants in our study about the appropriateness of an SMS approach as a broad invitation strategy for cervical screening. This is particularly true in the literature for participants representing different CALD communities, people experiencing physical or intellectual disabilities or with differing technological or English literacy (Morgan et al. 2022; Whitehead et al. 2023; Power et al. 2024). FGD data suggested that SMSs sent from Government bodies or NGOs may in fact deter participant engagement given the prevalence of SMS scams. Similar issues surrounding maintaining participants’ privacy and confidentiality were also raised, particularly for participants who required assistance in translating SMSs through family members (Whitehead et al. 2023). Consideration should also be given to tailoring mHealth strategies to specific population needs through end-user engagement (Matthew-Maich et al. 2016; Whitehead et al. 2023). Common themes across the literature include the use of simple language, easy use and linkage with existing support systems, which could extend to trusted relationships with general practice (Morgan et al. 2022; Whitehead et al. 2023; Power et al. 2024).

GP and/or practice endorsement is a highly effective strategy for increasing cancer screening participation – for both bowel and cervical screening; particularly important when choosing to screen via self-collection (Verbunt et al. 2022; Zammit et al. 2023). Most survey respondents reported wanting to receive an SMS from their general practice (82%), as a reminder to complete cervical screening (97% of 117; Table 3) with their first name (71%) and clinic named included (58%). General practice or provider endorsement alone has been shown to increase cancer screening participation by 2–20% across screening types (Duffy et al. 2016), although additional research suggests that discussions surrounding the endorsement significantly influence screening behaviour more than endorsement alone (Peterson et al. 2016). Approximately two-thirds (67%) of survey respondents indicated they would pay more attention to the SMS if it were from the NCSR. The NCSR could enhance their role in invitations and reminders with the use of SMS approaches, as recent national monitoring data indicated a low response to written reminder letters, with 16.3% of eligible participants completing screening within 6 months of invitation (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023). However, aligning with recommendations in the Elimination Strategy (Australian Centre for the Prevention of Cervical Cancer 2023), the NCSR are now sending reminder SMSs (with mention of self-collection) to overdue participants who indicated this preference and who have not responded (i.e. completed screening) to the initial invitation.

Our study considers the multitude of contextual and socio-cultural factors that may influence acceptability of mHealth strategies from an end-user perspective; particularly from women aged ≥50 years, living regionally/rurally and from CALD communities. Given the low likelihood of people changing mobile phone numbers compared with postal address, SMS screening invitations from general practice is a logical development for the NCSP. However, this study also demonstrates that without careful consideration, strategies such as these might further perpetuate inequity rather than addressing it.

Limitations of our study include that it was only conducted in one Australian state, Victoria, and does not reflect the national eligible screening population. Furthermore, most respondents to our survey (77%) were already aware of self-collection. Further exploring the utility of SMS in raising awareness among a population in which the majority were not aware of self-collection may reveal different views.

Not all priority populations were represented on the CCAP or among participants, such as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples or people with an intellectual disability. Our approach also assumes that all general practices are offering a choice of screening options, as recommended by the NCSP, which may not be the case in practice (Creagh et al. 2024). Although the FGD response rate was low at 20%, we observed consistent themes across the discussions. Our approach does not address logistical barriers, such as primary care accessibility and screening costs (e.g. transportation or mixed-billing services), although this reflects the limitations of the intervention’s scope, not the study itself. Although the study has not considered the implementation of SMS reminders from the general practice perspective, recent research suggests that this approach would be feasible and sustainable to implement (McIntosh et al. 2024).

Conclusion

This study provides information to guide the development of SMS-based strategies for cervical screening for use by general practices within the NCSP. This work is aligned with key policy actions in Australia’s Elimination Strategy for cervical cancer. Careful consideration should be taken when developing such strategies to support participation in national preventative health programs, given the specific needs of priority populations with diverse use of digital technologies, differing English and health literacy or intellectual and physical abilities.

Data availability

The participants of this study gave written consent for their data to be shared publicly as long as responses were anonymised. These datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and ethical approval requirements.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report there are the following competing interests to declare. JMB is a past employee of Australian Centre for the Prevention of Cervical Cancer (ACPCC). ACPCC have received donated HPV tests and equipment from multiple manufacturers for HPV validation and research studies.

Declaration of funding

This work was supported by the Victorian Department of Health through a Mid-Career Fellowship (MCRF21039).

References

Allen-Leigh B, Uribe-Zuniga P, Leon-Maldonado L, Brown BJ, Lörincz A, Salmeron J, Lazcano-Ponce E (2017) Barriers to HPV self-sampling and cytology among low-income indigenous women in rural areas of a middle-income setting: a qualitative study. BMC Cancer 17(1), 734.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Amos N, Lim G, Buckingham P, Lin A, Liddelow-Hunt S, Mooney-Somers J, Bourne A (2024) Rainbow realities: in-depth analyses of large-scale LGBTQA+ health and wellbeing data in Australia. La Trobe. Available at https://opal.latrobe.edu.au/articles/report/Rainbow_Realities_In-depth_analyses_of_large-scale_LGBTQA_health_and_wellbeing_data_in_Australia/24654852/2

Arbyn M, Smith SB, Temin S, Sultana F, Castle P, Collaboration Self-Sampling and HPV Testing (2018) Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: updated meta-analyses. BMJ 363, k4823.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Australian Centre for the Prevention of Cervical Cancer (2023) National Strategy For the Elimination of Cervical Cancer. Available from https://issuu.com/vcsreports/docs/national_cervical_cancer_elimination_strategy_-_no?fr=xKAE9_zU1NQ [cited 4 December 2023]

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) National Cervical Screening Program monitoring report 2023, 2023, catalogue number CAN 157. AIWH, Australian Government. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/cancer-screening/ncsp-monitoring-2023/summary

Azar D, Murphy M, Fishman A, Sewell L, Barnes M, Proposch A (2022) Barriers and facilitators to participation in breast, bowel and cervical cancer screening in rural Victoria: a qualitative study. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 33(1), 272-281.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Brotherton J, Machalek D, Smith M, Pagotto A, Canfel K, Saville M, Zammit C, Liang HY-L, Bateson D, Butler T, Hawkes D, Lee A, Macartney K, Mitchell L, Mohamed Y, Chacon GP, Rasmussen S, Vajdic C, Whop L (2024) 2024 Cervical cancer elimination progress report: Australia’s progress towards the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. Australian Centre for the Prevention of Cervical Cancer, Melbourne, Australia. Available at https://report.cervicalcancercontrol.org.au/

Cancer Council Australia (2022) 12. HPV screening strategies for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Clinical Guidelines for Cervical Screening. Available from https://www.cancer.org.au/clinical-guidelines/cervical-cancer-screening/hpv-screening-in-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-women

Chandrakumar A, Hoon E, Benson J, Stocks N (2022) Barriers and facilitators to cervical cancer screening for women from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds; a qualitative study of GPs. BMJ Open 12(11), e062823.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Creagh NS, Boyd LAP, Bavor C, Zammit C, Saunders T, Oommen AM, Rankin NM, Brotherton JML, Nightingale CE (2023) Self-collection cervical screening in the Asia-Pacific region: a scoping review of implementation evidence. JCO Global Oncology 9, e2200297.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Creagh NS, Saunders T, Brotherton J, Hocking J, Karahalios A, Saville M, Smith M, Nightingale C (2024) Practitioners support and intention to adopt universal access to self-collection in Australia’s National Cervical Screening Program. Cancer Medicine 13(10), e7254.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Duffy SW, Myles JP, Maroni R, Mohammad A (2016) Rapid review of evaluation of interventions to improve participation in cancer screening services. Journal of Medical Screening 24(3), 127-145.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Fullerton MM, Ford C, D’Silva C, Chiang B, Onobrakpor S-I, Dievert H, Yang H, Cabaj J, Ivers N, Davidson S, Hu J (2024) HPV self-sampling implementation strategies to engage under screened communities in cervical cancer screening: a scoping review to inform screening programs. Frontiers in Public Health 12, 1430968.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gertig D, Lee J (2023) Supporting health care providers in cancer screening: the role of the National Cancer Screening Register. The Medical Journal of Australia 219(3), 94-98.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Liu X, Ning L, Fan W, Jia C, Ge L (2024) Electronic health interventions and cervical cancer screening: systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research 26(1), e58066.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Machado Colling A, Creagh NS, Gogia N, Wyatt K, Zammit C, Brotherton JML, Nightingale CE (2024) The acceptability of, and informational needs related to, self-collection cervical screening among women of Indian descent living in Victoria, Australia: a qualitative study. Health Expectations: An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy 27(1), e13961.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

MacLaughlin KL, Jenkins GD, St Sauver J, Fan C, Miller NE, Meyer AF, Jacobson RM, Finney Rutten LJ (2024) Primary human papillomavirus testing by clinician- versus self-collection: awareness and acceptance among cervical cancer screening-eligible women. Journal of Medical Screening 31(4), 223-231.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Matthew-Maich N, Harris L, Ploeg J, Markle-Reid M, Valaitis R, Ibrahim S, Gafni A, Isaacs S (2016) Designing, implementing, and evaluating mobile health technologies for managing chronic conditions in older adults: a scoping review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 4(2), e29.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McIntosh JG, Jenkins M, Wood A, Chondros P, Campbell T, Wenkart E, O’Reilly C, Dixon I, Toner J, Martinez-Gutierrez J, Govan L, Emery JD (2024) Increasing bowel cancer screening using SMS in general practice: the SMARTscreen cluster randomised trial. British Journal of General Practice 74(741), e275-e282.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Morgan KA, Wong AWK, Walker K, Desai RH, Knepper TM, Newland PK (2022) A mobile phone text messaging intervention to manage fatigue for people with multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, and stroke: development and usability testing. JMIR Formative Research 6(12), e40166.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Peterson EB, Ostroff JS, DuHamel KN, D’Agostino TA, Hernandez M, Canzona MR, Bylund CL (2016) Impact of provider-patient communication on cancer screening adherence: a systematic review. Preventive Medicine 93, 96-105.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Power R, Ussher JM, Hawkey A, Missiakos O, Perz J, Ogunsiji O, Zonjic N, Kwok C, McBride K, Monteiro M (2022) Co-designed, culturally tailored cervical screening education with migrant and refugee women in Australia: a feasibility study. BMC Women’s Health 22(1), 353.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Power R, David M, Strnadová I, Touyz L, Basckin C, Loblinzk J, Jolly H, Kennedy E, Ussher J, Sweeney S, Chang E-L, Carter A, Bateson D (2024) Cervical screening participation and access facilitators and barriers for people with intellectual disability: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry 15, 1379497.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ (2017) Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Services Research 17(1), 88.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Serrano B, Ibáñez R, Robles C, Peremiquel-Trillas P, De Sanjosé S, Bruni L (2022) Worldwide use of HPV self-sampling for cervical cancer screening. Preventive Medicine 154, 106900.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Staley H, Shiraz A, Shreeve N, Bryant A, Martin-Hirsch PPL, Gajjar K (2021) Interventions targeted at women to encourage the uptake of cervical screening. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 9(9), CD002834.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Temminghoff L, Russell C, Andersson T, Broun K, McGrath N, Wyatt K (2024) Barriers and enablers to participation in the National Cervical Screening Program experienced by young women and people with a cervix aged between 25 and 35. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 35(2), 376-384.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Thomas J, McCosker A, Parkinson S, Hegarty K (2023) Measuring Australia’s digital divide: the Australian digital inclusion index 2023. RMIT University. Available at https://apo.org.au/node/323092

Verbunt E, Boyd L, Creagh N, Milley K, Emery J, Nightingale C, Kelaher M (2022) Health care system factors influencing primary healthcare workers’ engagement in national cancer screening programs: a qualitative study. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 46(6), 858-864.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Verbunt EJ, Newman G, Creagh NS, Milley KM, Emery JD, Kelaher MA, Rankin NM, Nightingale CE (2024) Primary care practice-based interventions and their effect on participation in population-based cancer screening programs: a systematic narrative review. Primary Health Care Research & Development 25, e12.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Welsh EF, Andrus EC, Sandler CB, Moravek MB, Stroumsa D, Kattari SK, Walline HM, Goudsmit CM, Brouwer AF (2024) Cervicovaginal and anal self-sampling for human papillomavirus testing in a transgender and gender diverse population assigned female at birth: comfort, difficulty, and willingness to use. Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. Available at https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/lgbt.2023.0336

Whitehead L, Talevski J, Fatehi F, Beauchamp A (2023) Barriers to and facilitators of digital health among culturally and linguistically diverse populations: qualitative systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 25, e42719.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Yeh PT, Kennedy CE, De Vuyst H, Narasimhan M (2019) Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Global Health 4(3), e001351.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Zammit CM, Creagh NS, McDermott T, Smith MA, Machalek DA, Jennett CJ, Prang K-H, Sultana F, Nightingale CE, Rankin NM, Kelaher M, Brotherton JML (2022) “So, if she wasn’t aware of it, then how would everybody else out there be aware of it?”—key stakeholder perspectives on the initial implementation of self-collection in Australia’s cervical screening program: a qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19(23), 15776.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Zammit C, Creagh N, Nightingale C, McDermott T, Saville M, Brotherton J, Kelaher M (2023) ‘I’m a bit of a champion for it actually’: qualitative insights into practitioner-supported self-collection cervical screening among early adopting Victorian practitioners in Australia. Primary Health Care Research & Development 24, e31.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |