Engaging citizens to conduct large-scale qualitative research: lessons learnt from a community-engaged research project on queer men’s lived experiences of health in Singapore

Shao Yuan Chong A # , Benedict Xin Hao Tan B # , Daniel Weng Siong Ho B # , Ye Xuan Wee

A # , Benedict Xin Hao Tan B # , Daniel Weng Siong Ho B # , Ye Xuan Wee  C * , Muhammad Hafiz bin Jamal D , Rayner Kay Jin Tan

C * , Muhammad Hafiz bin Jamal D , Rayner Kay Jin Tan  E and

E and A

B

C

D

E

# These authors contributed equally to this paper

Handling Editor: Ucheoma Nwaozuru

Abstract

HIV science has made significant progress, but community engagement in some contexts remains suboptimal, with marginalized and key populations being left behind. Discriminatory policies, medical mistrust, stigma and a lack of resources remain key roadblocks. Citizen-led, community-engaged approaches hold promise in subverting power structures that reproduce such barriers and allow us to leverage community resources.

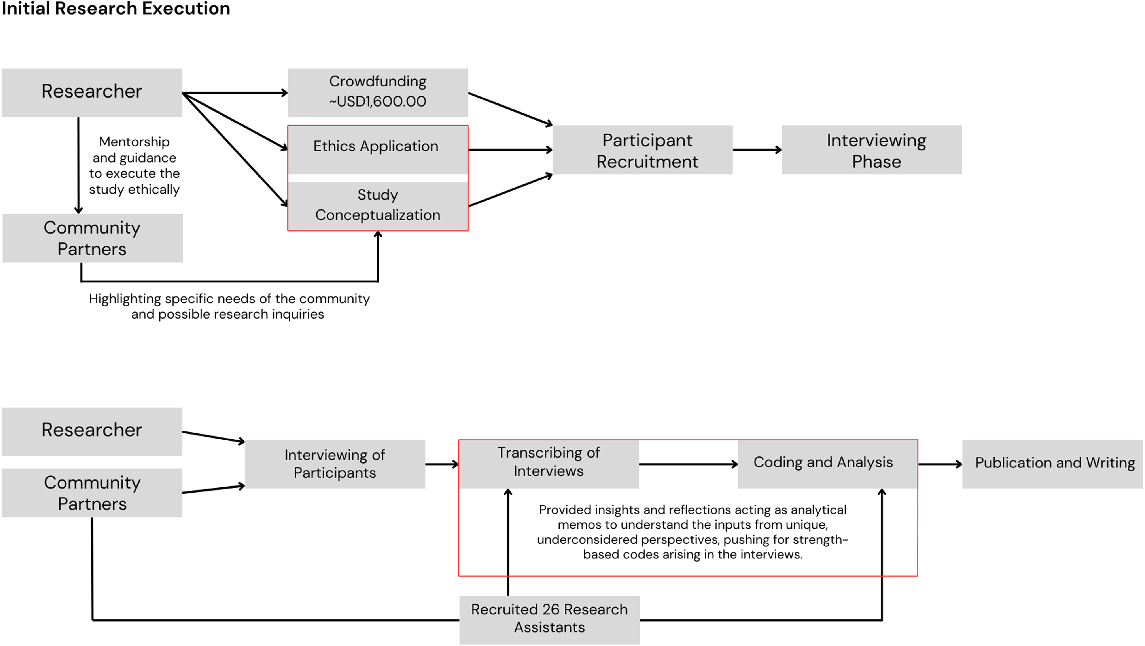

We draw on our experience of a collaborative research project between the National University of Singapore and RainbowAsia, a community-based organization addressing the needs of young gay, bisexual and queer men in Singapore. The study focused on stigma, resilience, relationships, sexual partnerships and mental health among Singaporean gay, bisexual and queer men, and commenced in June 2022. Despite being a high-income country, research funding for HIV key populations in Singapore remains sparse, as local funders prioritize less politically sensitive topics while international funders rightfully focus funding on resource limited settings. A citizen-led approach was therefore implemented out of necessity and a desire by community members to translate research into evidence-based programs. We propose a citizen science framework comprising eight key phases, including: (1) developing a research and implementation pipeline, (2) stakeholder and resource mapping, (3) delegation of expertise, (4) creating plans for equity, (5) developing a research plan, (6) generating evidence, (7) dissemination and translation, and (8) plans for sustainability and impact. Cross-cutting processes across all phases include the adoption of deliberative democratic processes, training and mentorship, and (re)negotiation of power and recognition for all stakeholders. A total of 44 in-depth interviews were completed, transcribed, and analyzed by a core research team and 26 volunteer research assistants. The entire study required crowdfunding USD1600.00 for participant reimbursements, but otherwise leveraged academic, community and citizen resources to accomplish the study’s outputs.

Our case study illustrates a microcosm of how research evidence can be generated, disseminated, and translated by citizens and communities into evidence-based programs at the community level. Our framework aligns itself with stakeholder engagement principles, and can provide a roadmap for sustainable collaborative research between academic, community and citizen stakeholders.

Keywords: citizen science, community engagement, HIV key population, LGBTQIA+, participatory research, qualitative research, Singapore, stakeholder engagement.

Introduction

Citizen science approaches typically involve the engagement of non-academics in various stages of the research process,1 and have several benefits for research. First, it promotes a democratization of the research process by ensuring that the lived experiences of citizens are incorporated into the research process.2,3 Second, it also serves as a form of ‘crowdfunding,’4 and harnesses community resources and empowers community members to advance scientific research in supporting marginalized or key populations.5 Therefore, citizen science approaches can enable research efforts to be executed and sustained with minimal funding.6 Finally, citizen involvement also has the potential to build scientific literacy among lay people and improve their knowledge of the subject matter.7

Citizen involvement in research spans a wide range of activities. It varies on a spectrum, from consulting community members and utilizing volunteers for data generation, to empowering community members to shape research questions and methodologies.8,9 Several participatory tools, such as co-creation groups10 and crowdsourcing approaches, have been utilized to engage citizens and communities in several aspects of solving health-related problems and developing solutions to them.11 Citizens have also been involved in the planning, developing, delivering, evaluating, and scaling up of clinical HIV and sexually transmitted infections services.12 Nevertheless, scholars have more recently highlighted that many studies that engage the community only do so in the later stages of research, and not in postulating research questions or hypotheses.13

Citizen science may be especially useful for studies in sexual health surrounding vulnerable populations, given that communities affected by sexual health-related risks are often disproportionately impacted by stigma, and that public funding for sexual health-related programmes are often suboptimal in many contexts. Past citizen science research has highlighted the method’s efficacy in addressing the HIV key populations, including the LGBTQIA+ community – however, adoption of this framework has been limited given the lack of an implementable framework available in guiding the process of adoption.14 This Method Matters article seeks to contribute to this body of literature by describing our experience of developing a citizen science, collaborative research project between the National University of Singapore and RainbowAsia that focused on stigma, resilience, relationships, sexual partnerships, and mental health among Singaporean gay, bisexual and queer (GBQ) men.

Discussion

Despite the repeal of the anti-sodomy law, Section 377A, in 2022, structures (e.g. restrictive education curriculums, enshrined cisheteronormative laws and health policies) remain in place that prevent health equity from being achieved for LGBTQIA+ individuals. To-date, research has continued to find greater health disparity (including physical, mental and sexual health) among LGBTQIA+ populations in Singapore, as compared with cisheterosexual populations, especially given the higher rates of stigma they experience in their everyday lives, as well as in medical settings.15–19 Funding opportunities remain restricted for LGBTQIA+-related topics and work, preventing resources from being readily available for LGBTQIA+ individuals, even in the case of health-related concerns.20

The study started with a Singapore-based queer community group, RainbowAsia (SY, YXW, MHJ), reaching out to academic researchers, RT and DH, to design and collaborate on the study (‘the core team’). Traditionally, RainbowAsia has focused on advancing the welfare of GBQ+ men in Singapore from a social perspective, but since 2022, the vision of RainbowAsia has changed to encompass the broader LGBTQIA+ community in Singapore. Rainbow+ was the research arm of RainbowAsia. Adhering to the principles of self-determination (‘Nothing about us without us’),21 the community group and academic researchers agreed that this will be a community-led and grounded project. All parties agreed that the best approach toward ensuring the community-grounded nature of this study is by employing the citizen science model, where the research process wholly involved the community group from conceptualization up until publication. We drew on meeting minutes, notes, video recordings, transcripts and other forms of documentation to inform the writing of this manuscript.

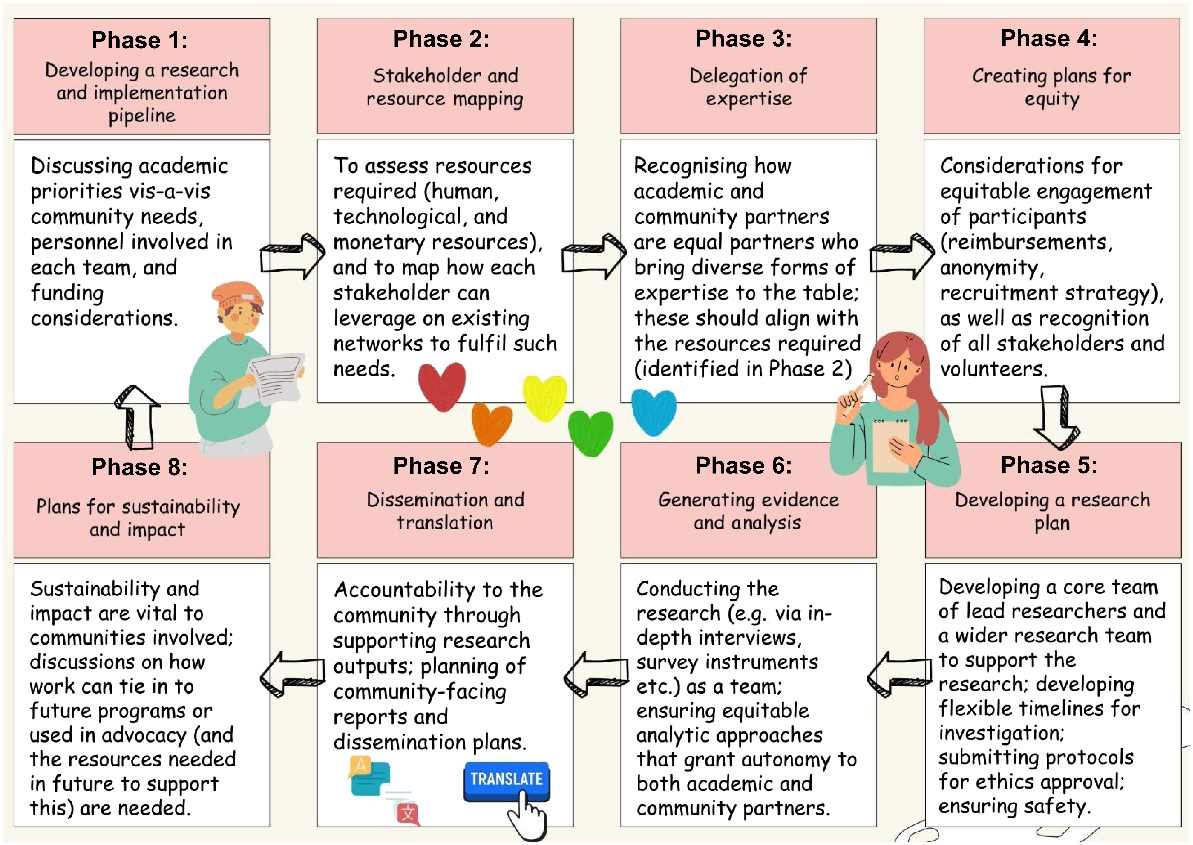

Our analysis of the citizen-science project revealed that our process was organized according to eight key phases. Specifically, these included: (1) developing a research and implementation pipeline, (2) stakeholder and resource mapping, (3) delegation of expertise, (4) creating plans for equity, (5) developing a research plan, (6) generating evidence, (7) dissemination and translation, and (8) plans for sustainability and impact. A summary of the process and key considerations can be found in Fig. 1.

Phase 1: Developing a research and implementation pipeline

This study was conceptualized to meet the goals of RainbowAsia, to inform the needs of GBQ men in Singapore such that social and education programs can be developed to meet these needs. The broad topics (e.g. stigma, resilience) were selected based on RainbowAsia’s identified needs rather than the specific theoretical or methodological contributions that researchers may have been more focused on advancing, highlighting the community centricity in decision-making in this research. Generally, researchers and community members were aligned in their approach and expectations given the researchers’ past experiences working with community-based participatory research, recognizing that community-based research should center the needs of the community first before considering more academically-focused goals. Having acquired at least a Bachelor’s level education, involved community members similarly were able to offer understandings and alternatives as academically-focused considerations (e.g. ethics) were brought up. During initial discussions, three points of discussions were raised.

First, the researchers and community members from RainbowAsia intentionally discussed academic perspectives and community needs, during which the community’s (RainbowAsia) desire to cover ‘all in a single study’ was highlighted as unfeasible from an academic perspective. To resolve the tension, the researchers and community members agreed that immediate community needs (e.g. issues of stigma and ways forward in the post-repeal era) will be prioritized to address the immediate needs, whereas more focused issues (e.g. adolescent experiences) will be addressed as separate studies after the first broader study. On this point, the stakeholders agreed that the key themes to be explored in this study included stigma, resilience, relationships, sexual partnerships, mental health, available resources and social support among Singaporean GBQ men.

Second, the researchers and community members discussed at what point who should be involved in the study, and what types of training may be required for community members’ involvement. Although there were thoughts about involving more community members, even at the research design and data collection stage, it was later decided that that would not be feasible, as it would require more community members to be trained to conduct the interviews ethically. Furthermore, given that the data were based on semi-structured interviews, it was agreed that the more interviewers involved, the higher the probability of the interviews being compromised in integrity in that the interviewers may have varying levels of understanding relating to the research design and aims of the interviews. We also wanted to ensure that all interviewers have had sufficient experience with offering psychological safety for the participants given the sensitivity of the topics. Consequently, it was decided that the nuclear team of five (including two researchers and three community members) would lead the design and data collection, before involving more community members in the data processing and analysis stage. To ensure the integrity of the research can still be preserved while keeping the study grounded, it was also agreed that the researchers on the team will guide the research process while encouraging inputs from involved community members at all stages, and provide training where required to community members.

Finally, the issue of funding for all stakeholders was highlighted as a point of concern given that the community group was a fully volunteer-run organisation. Acknowledging that the community researchers are offering time and effort in their additional capacities to contribute to the research process, explicit discussions were made with all community volunteers to establish how they can benefit from the process tangibly (e.g. in terms of building their portfolios), as well as intangibly (e.g. in terms of skills and social bonds). In discussion with the researchers and in agreement among all community members, it was also agreed that the researchers would tap into their past experience and lead the crowdsourcing of funds to at least ensure that the participants were equitably reimbursed.

Phase 2: Stakeholder and resource mapping

Three key resources were identified to be essential for this study: human resources (i.e. manpower), technological resources and monetary resources (for reimbursement to ensure equitable participation). The entire study required crowdfunding USD1600.00 for participant reimbursements, but otherwise leveraged academic, community and citizen resources to accomplish the study’s outputs. The academic researchers specifically provided additional time and access to the Institutional Review Board through their institutional affiliation (National University of Singapore) before embarking on the study. Although the academic researchers were listed as Principal Investigators for the study, the community researchers were listed as Co-Investigators to highlight the level of contribution the community partners were involved in. For the community partners, RainbowAsia established a new research branch with research staff to advance their vision of empirically informing their programs, with the discussed study being the starting point. For the citizens involved in this study, specifically, the volunteers’ networks with the wider community, and their past trainings and perspectives were engaged to ensure that the study accounted for wide-ranging experiences that exist within the LGBTQIA+ community. The academic researchers offered the involved community members with capacity building, including mentorship (see Phase 6 on subgroup mentorship) and workshop trainings on transcription, coding and analysis to ensure that sufficient skills and knowledge were acquired before formal coding and analysis took place.

Phase 3: Delegation of expertise

In recognition of the strengths of the researchers and the community partners, the researchers focused on meeting the academic requirements, financial needs and the actual execution of the study, shown in Fig. 2.

Phase 4: Creating plans for equity

To ensure equitable participation, the core team discussed and achieved consensus on several aspects of the study. These included: (1) the level of participant reimbursement to ensure equitable participation from a wider pool of participants (e.g. socioeconomically disadvantaged participants); (2) how purposive sampling would be employed to ensure that minoritized community members within the GBQ+ community (e.g. racialized GBQ+ individuals, trans-identifying GBQ+ individuals, neurodivergent individuals etc.) had equal opportunity to be recruited; (3) the need to allow for online interviews to allow for easier access and greater anonymity for participants who may not be comfortable revealing their identities for the purposes of the study; and (4) plans for dissemination of the study results in a non-academic format and promising all participants that they can receive the report.

Three key approaches were adopted to ensure equitable involvement of the volunteers. First, volunteers were accepted based on their ability to commit, their ability to read and understand English (which is the official language of Singapore), and no other criteria. In allowing volunteers of diverse demographics to participate, the setup of this research also offered opportunities for diverse inputs and opinions from the LGBTQIA+ community itself, which at its core benefits the research project in terms of its efficacy in representing the diverse nature of Singapore’s LGBTQIA+ community. Second, to ensure that volunteer research assistants benefit from the experience through appropriate mentorship, volunteer research assistants were then distributed into groups of four or five, each group of which were mentored by the core research team.

Phase 5: Developing a research plan

The core team agreed that the projected timeline would be subject to changes, adjusted according to how the entire research team (including the volunteer research assistants) coped with the study alongside their other commitments. The core team started conceptualizing the study and applying for ethics in June 2022, with the plan of starting interviews in September 2022. Thereafter, from September to December 2022, the core team conducted the interviews. From January to April 2023, the core team and the newly-recruited volunteers engaged in transcription. At the time of writing, plans were made for coding and analysis to take place until December 2023, before engaging in publication writing from January 2024. Community partners and volunteer research assistants began using the data from interviews as case studies for academic conferences, presentations and relevant publications (see Supplementary Figs. 3–5).

To ensure safety for participants, all research processes adhered to academic and ethics guidelines set forth by the National University of Singapore’s Institutional Review Board (NUS-IRB-2022-356). With regard to safety for volunteers, they were briefed about the topics that could come up during the interviews to ensure volunteers had the chance to sound out should some topics or transcripts potentially bring about distress for them that they may not wish to tackle. In choosing to group the volunteers in the research process (see Phase 6 for more information), the core research team sought to ensure volunteers had a space for social support, especially when tackling difficult topics (e.g. discussions of stigma, suicide, sexual violence), while at the same time, also providing a space for exchange of ideas. Further, it created an avenue for social bonds to be built within the LGBTQIA+ community by working toward a common goal of completing this research study.

Phase 6: Generating evidence and analysis

The academic researchers and community group members in the core team conducted all 44 semi-structured interviews, and the 26 volunteer research assistants supported the transcription and analysis. We introduced a single, tailor-made citizen-led coding effort where all 26 volunteers and the five core team members were involved. Subgroups were created where a member of the core team served as the group leader, with approximately four or five volunteer research assistants in each group. These volunteers received training on coding first, engaged in coding within their own subgroups, before the subgroups came together to merge the codes together to form a master coding frame. The subgroups served as both an avenue to engage in coding within a more dedicated space, but also provided dedicated attention by a mentor personnel to address concerns for individual volunteers that may arise in the course of the research analysis process. Large group meetings involving all researchers took place fortnightly, meeting for the consolidation of codes from each subgroup, before coding frames are further refined by the core team members in a separate meeting in the same week. Time conflicts and outside commitments have made time a primary resource constraint; to ensure that all volunteers were able to have their inputs included despite this constraint, the research team members took a liberal approach in adjusting the timelines, and changes were made in consultation with all volunteers involved in coding. Aside from the ongoing large team coding, individuals who were interested in coding separately for their independent analysis and developing research output were encouraged to do so. After the coding phase, volunteers who remained interested were asked to join analysis groups based on themes of interest, during which core research members provided mentorship on how to analyze data to translate them into formal research publications.

Phase 7: Dissemination and translation

The dissemination plan was determined in discussion between the academics and the community group members to ensure that all stakeholders’ interests were protected. In adherence to the goal of empowering the LGBTQIA+ community in the course of their involvement, on an academic level, volunteers were invited to innovate with the data set to produce academic outputs that they found aligning with their interest.22–26 Volunteers were also encouraged to participate in conferences and publication writing in settings where they found appropriate. On a community-level, RainbowAsia, as a community group, will also produce a public-facing report based on the consolidated codes, to inform social programs and policies intended to meet the needs of GBQ men in Singapore. All volunteers involved in this study will be credited as coauthors on the community report.

Phase 8: Plans for sustainability and impact

Beyond the community paper and publication production, the pool of volunteer research assistants who have supported this study have been invited to expand on parts of this study, should they be interested. This will also ensure that subthemes of this study can be deepened beyond this study. Volunteers have reflected that this has been a sustainable mode of community contribution, as they can directly witness the skills and social bond development among themselves. The core research and community team has also explored opportunities to continue pursuing new threads of research from within the community, to ensure that professional development can continue to the extent the volunteers desire. Although overall, maintaining motivation and sustained mentorship has required dedicated resources that can pose a challenge for a fully volunteer-run community research team, negotiations around available resources and flexibility has ensured that these challenges can be overcome, and limitations can be addressed.

Conclusion

Conceptualized with the research question to examine the lives of queer men in Singapore, the use of a citizen science model was intentional in centering community involvement as a key component that featured strongly from conceptualization to publication. Specifically, the involvement of community members via the democratization of the research process allowed for the project to be informed by the felt needs and lived experiences of the community.2 Our process of citizen-engaged science also resonates strongly with a consensus statement on the principles of stakeholder engagement in research published by Goodman et al.13 A summary of the eight statements for which consensus were achieved may be found in Supplementary Table S2, alongside a description of how our work aligned with these statements.

We are mindful of some limitations of this approach. First, although the group was highly engaged due to the inclusiveness of the process and flexibility provided to volunteers, several volunteers from the community did drop out of participating in the project. Understanding the reasons for such drop out and potential mitigating strategies would be important to bolster future citizen-led and community-engaged research. Second, the qualitative nature of this study provided a very dynamic research paradigm that allowed the team to iteratively make changes to processes, and the insights from this study may not apply to all study designs. Third, the experiences highlighted in this manuscript reflect that of a high-income country setting. We anticipate that there may be different competing demands for community partners and citizen volunteers in low-to-middle-income settings. Nevertheless, the low level of financial resources required to execute this citizen science project may help bridge such differences.

In sum, our case study illustrates a microcosm of how research evidence cannot only be generated, but disseminated and translated by citizens and communities into evidence-based programs at the community level. Our framework integrates citizen science, community engagement and qualitative research, and can provide a roadmap for sustainable collaborative research between academic, community and citizen stakeholders.

Data availability

The data that support this study cannot be publicly shared due to ethical or privacy reasons and may be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author if appropriate.

Author contributions

SYC, DH, YXW, MHJ and RT conceptualized the study; SYC, DH, YXW, MHJ and RT conducted all interviews; BT, SYC, DH, YXW, MHJ and RT analyzed the data; RT provided supervision and resources for this study. BT, SYC, DH, YXW and RT wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank all participants who took part in this study. We are also grateful to RainbowAsia and all volunteer research assistants for their contributions to this study.

References

1 Amirrudin A, Harrigan N, Naqvi I. Scaled, citizen-led, and public qualitative research: a framework for citizen social science. Curr Sociol 2023; 71(6): 1019-1039.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical research council guidance. BMJ 2015; 350: h1258.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

4 Kpokiri EE, Sri-Pathmanathan C, Shrestha P, et al. Crowdfunding for health research: a qualitative evidence synthesis and a pilot programme. BMJ Glob Health 2022; 7(7): e009110.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

5 Silvertown J. A new dawn for citizen science. Trends Ecol Evol 2009; 24(9): 467-471.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

6 Bonney R, Phillips TB, Ballard HL, et al. Can citizen science enhance public understanding of science? Public Underst Sci 2016; 25(1): 2-16.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

9 Israel BA, Parker EA, Rowe Z, et al. Community-based participatory research: lessons learned from the Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environ Health Perspect 2005; 113(10): 1463-1471.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

10 Stark E, Ali D, Ayre A, et al. Coproduction with Autistic adults: reflections from the authentistic research collective. Autism Adulthood 2020; 3(2): 195-203.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

11 Wang C, Han L, Stein G, et al. Crowdsourcing in health and medical research: a systematic review. Infect Dis Poverty 2020; 9(1): 8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

12 Tan RKJ, Marley G, Kpokiri EE, et al. Participatory approaches to delivering clinical sexually transmitted infections services: a narrative review. Sex Health 2022; 19(4): 299-308.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

13 Goodman MS, Ackermann N, Bowen DJ, et al. Reaching consensus on principles of stakeholder engagement in research. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2020; 14(1): 117-127.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

14 Tan BXH, Chong SY, Ho DWS, et al. Fostering citizen-engaged HIV implementation science. J Int AIDS Soc 2024; 27(Suppl 1): e26278.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

15 O’Hara CA, Foon XL, Ng JC. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex (LGBTQI+) healthcare in Singapore: perspectives of non-governmental organisations and clinical year medical students. Med Educ Online 2023; et al. 28(1): 2172744.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

16 SG Mental Heath Matters. National Suicide Prevention Strategy White Paper. Project Hayat; 2024. Available at https://sgmentalhealthmatters.com/suicide-prevention

17 Tan RKJ, O’Hara CA, Koh WL, et al. Delineating patterns of sexualized substance use and its association with sexual and mental health outcomes among young gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in Singapore: a latent class analysis. BMC Public Health 2021; 21: 1026.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

18 Tan RK, Yang DW, Le D, et al. Minority statuses and mental health outcomes among young gay, bisexual and queer men in Singapore. J LGBT Youth 2023; 20(1): 198-215.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

19 Tan RKJ, Low TQ, Le D, et al. Experienced homophobia and suicide among young gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer men in Singapore: Exploring the mediating role of depression severity, self-esteem, and outness in the Pink Carpet Y Cohort Study. LGBT Health 2021; 8(5): 349-358.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

21 Harrison J. ‘Nothing about us without us’: GLBTI older people and older people living with HIV-prospects, possibilities and self-determination. HIV Australia 2010; 8(3): 10-12.

| Google Scholar |

22 Chong SY, Tan BXH, Ho DWS, et al. Relegated to and thriving in the margins: a case study analysis of narratives of stigma and resilience amongst gay, bisexual and queer (GBQ) men in Singapore from an intersectional lens. In Council of university directors of clinical psychology diversifying clinical psychology conference, Council of University Directors of Clinical Psychology, Virtual. 14–15 April; 2023.

23 Wee YX, Chong SY, Jamal MH et al. Lonely and forced to experiment without guidance: explaining positive correlational effects between casual sex behaviour and postcoital dysphoria amongst GBQ+ Men in Singapore. In Association for behavioral and cognitive therapies first annual student research symposium, Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, Virtual. 3 June; 2023.

Footnotes

§ Rainbow+ community volunteers involved in the project include (in alphabetical order): Abbrielle Low Jia Min, Aizuddin Zakaria, Anirudh Arun, Chek Yew Chuan (Martyn), Chong Zhao Yang (Daniel), Ethan Kan, Hau-Chi Hsu, Heong Kheng Boon, Hu Chenwei (Nathan), Hum Heh Ying (Erin), Jan Paolo Macapinlac Balagtas, Katherina Oh, Lee Tze Yan, Luna Grimm, Madelaine Wong, Mahahewage Anasta Rishee Bhagya Perera, Medha Acharya, Muhammad Daruthman Abrie Masjuri, Ng Yong Han, Saakshi Shah, Soh Soon Liang Elias, Tan Wen Kai, Tara Tseng-West, Teo Geng Hao, Toh Seng Wee (Chris), Van Gia Tuan (Shawn) and Vishnumaya Deepakchandran.