What information women want about intrauterine devices and contraceptive implants and where they want to receive this information: findings from an Australian online survey

Jacqueline Coombe A * , Ximena Camacho B C , Digsu N. Koye D C and Cassandra Caddy A

A * , Ximena Camacho B C , Digsu N. Koye D C and Cassandra Caddy A

A

B

C

D

Abstract

Information about contraceptive options is important for informed decision making. We aimed to understand the information needs and preferences of potential users of intrauterine devices and contraceptive implants, methods that are underutilised in Australia.

We conducted an online survey of Australian women aged 18–45 years. The survey comprised mostly close-ended questions, with a few opportunities for free-text comments.

In total, 1745 women participated in the survey. Participants had a mean age of 31 years; most identified as heterosexual (67%) and said that they were in a relationship (71%). Overwhelmingly, participants said that the most important information they wanted to know prior to using a contraceptive implant or intrauterine device was potential side effects (97%), signs that something is wrong (91%), effectiveness (90%), cost (87%), how and where to access the method (82%) and the experiences of other people who have used the method (81%). Most participants said that they go to their healthcare provider for information about contraception (86%). However, 78% said they also turn to the internet, and 15% said they use social media. When asked to indicate their preferred source of contraceptive information, participants reported their healthcare provider (93%), the internet (65%), friends (42%) and social media (20%).

Our findings suggest that those considering using contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices have clear information needs, and this information should be provided to consumers during contraceptive counselling by a healthcare provider. Although healthcare providers are a preferred and trusted source of information, participants also reported seeking information from the internet.

Keywords: contraception, contraceptive implant, health information, information needs, intrauterine device, long-acting reversible contraception, online survey, reproductive health, women, women’s health.

Introduction

Women of reproductive age (18–45 years) comprise around 20% of the total Australian population.1 The contraceptive methods used by most of these women are the oral contraceptive pill and male condoms; approximately one-third of contraceptive users, respectively. Far fewer (approximately 10% of contraceptive users) use intrauterine devices (IUDs) and contraceptive implants, collectively referred to as long-acting reversible contraception (LARC).2–4 LARC is very effective at preventing pregnancy (>99% efficacy) for up to 10 years depending on the device selected.5 In addition, the 52 mg levonorgestrel IUD can also be used for non-contraceptive benefits such as the management of heavy menstrual bleeding and endometriosis.6 All types of LARC need to be inserted into the body by a healthcare provider.

Access to a range of contraceptive options is vital to reproductive decision making as well as the management of reproductive conditions. However, research to date has clearly demonstrated that access and information barriers are hindering uptake of LARC for Australian women.7,8 In particular, past research has noted that many women perceive LARC to only be suitable for people who have given birth or for people in monogamous relationships,9,10 neither of which is a requirement according to Australian contraceptive guidelines,11 or only be considered a viable contraceptive option after other methods have been unsuccessfully used.12,13

A recent Australian study demonstrated that the availability of high-quality information about LARC can increase uptake.10 However, further work is needed to understand the specific information needs of women who may be considering these methods. In the current study, we aimed to understand what information people want about LARC prior to use (among those who have and have not used these devices), where people usually access contraceptive information, where they want to access this information and who they trust to provide contraceptive information.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a cross-sectional online survey of Australian women aged 18–45 years between 24 August and 19 September 2022 using Qualtrics survey software. We utilised reporting guidelines CHERRIES14 and STROBE15 to guide our study. Participants were recruited via paid social media advertising (Facebook and Instagram) and via the research networks of the authors (e.g. posting the recruitment flyer on X). Although we recognise that recruiting online in this way poses challenges, including potentially fraudulent responses, we did not experience this issue during our study (see our recent publication regarding recruiting for this survey for more details16). Participants who completed the survey and provided an email address went into a prize draw for 1 of 10 A$20 gift vouchers. This study received ethics approval from The University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (ID: 23972).

Participants

Women and people with female reproductive organs who were aged 18–45 years, were living in Australia and provided informed consent were eligible to participate. We aimed to recruit 500 women to the survey. This sample size was chosen to allow estimation of proportions with a 95% confidence level and a precision of approximately ±4.5%, assuming an expected 50% proportion of participants who wished to know about potential side effects, which provides the most conservative estimate.

Variables and data measurement

The survey comprised mostly close-ended questions. We collected information on respondent demographic, sexual and reproductive characteristics. All participants were asked about current and previous contraceptive use to understand participants contraceptive history, including past or current LARC use (see Supplementary material Table S1).

Outcomes

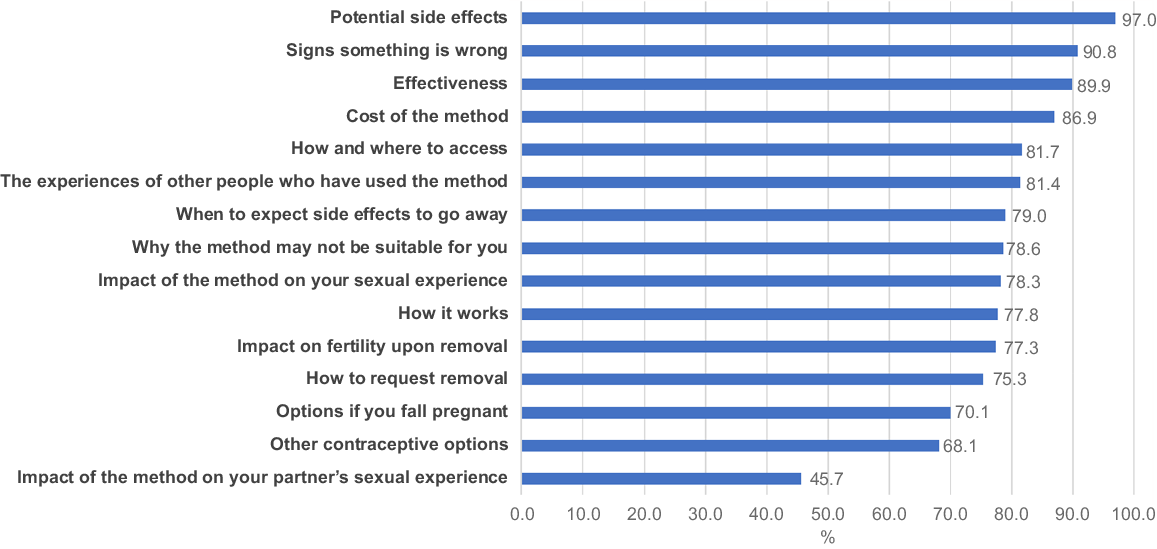

Our primary outcome was to identify the information about LARC that participants deemed most important. All participants were asked, ‘What sorts of information do you think is important to know before deciding whether to use a contraceptive implant or intrauterine device (IUD)?’. They were provided with a list of 15 options (Fig. 1), of which they could select as many as they wished. A free-text box for options not listed was also provided.

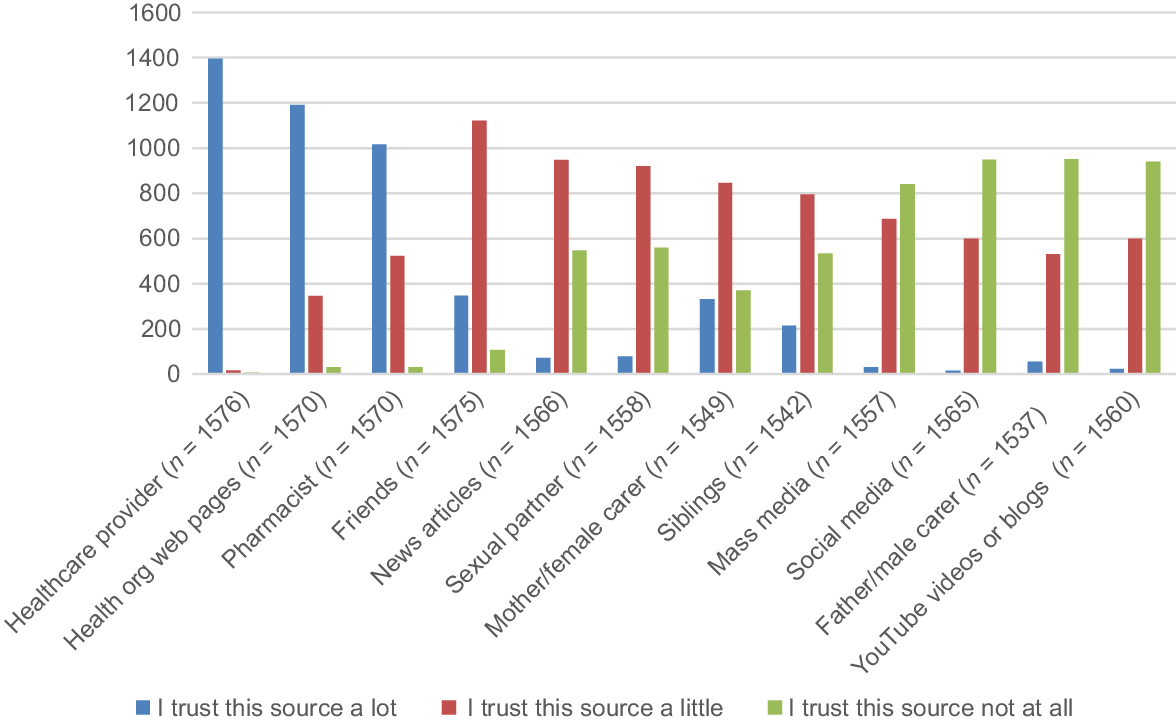

We had two secondary outcomes. The first was to identify the sources through which participants usually access information. Participants were asked where they usually get information about contraception and were provided with a list of 10 multiple-choice options. Participants were then asked where they would like to get information about contraception and were provided with the same list of 10 options from which they could select as many options as they liked. Our other secondary outcome was to identify the sources trusted by participants to provide accurate information about contraception. Participants were given a list of 12 sources, and for each source, participants were asked to rate their trust using a three-point scale (a lot, a little, not at all).

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of respondents were described using mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) for continuous variables, and number and percentages for categorical variables. We used descriptive statistics (number and percentage of respondents) to describe the primary as well as secondary outcomes of the study. All analyses were completed using SAS ver. 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Participant characteristics

In total, 1745 women participated in the survey. Participants had a mean (s.d.) age of 31 years (7.3), and 1150 (67%) identified as heterosexual, 1207 (71%) said that they were in a relationship and 1570 (93%) reported being ever sexually active (Table 1). Nearly three quarters had attained a university degree (1223, 71%), and nearly a quarter lived outside a metropolitan area (416, 24%) (see Table 1).

| Characteristics | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean, s.d. | 30.9 | 7.3 | |

| Gender identity A (missing: n = 29) | |||

| Woman | 1666 | 97.1 | |

| Gender diverse | 50 | 2.9 | |

| Sexuality B (missing: n = 32) | |||

| Heterosexual/straight | 1150 | 67.1 | |

| Gay/lesbian | 40 | 2.3 | |

| Bisexual/pansexual | 343 | 20.0 | |

| Something else | 180 | 10.5 | |

| Relationship status C (missing: n = 42) | |||

| Single | 376 | 22.1 | |

| Casually dating | 85 | 5.0 | |

| In a relationship | 1207 | 70.9 | |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 22 | 1.3 | |

| Something else | 13 | 0.8 | |

| Ethnicity D (missing: n = 31) | |||

| Australian | 1439 | 84.0 | |

| Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander | 19 | 1.1 | |

| Asian | 161 | 9.4 | |

| African or Middle Eastern | 18 | 1.1 | |

| European | 258 | 15.1 | |

| North American | 27 | 1.6 | |

| South or Central American | 13 | 0.8 | |

| Something else | 86 | 5.0 | |

| Residency status E (missing: n = 36) | |||

| Australian citizen | 1576 | 92.2 | |

| Other visa options, lived in Australia for >5 years | 60 | 3.5 | |

| Other visa options, lived in Australia for ≤5 years | 73 | 4.3 | |

| Employment F (missing: n = 39) | |||

| No | 341 | 20.0 | |

| Yes | 1365 | 80.0 | |

| Current student G (missing: n = 39) | |||

| No | 1246 | 73.0 | |

| Yes | 460 | 27.0 | |

| Highest level of education completed (missing: n = 41) | |||

| Secondary school or less | 287 | 16.8 | |

| College, technical, trade certificate or diploma | 194 | 11.4 | |

| University degree | 1223 | 71.8 | |

| Remoteness (missing: n = 23) | |||

| Metropolitan | 1306 | 75.8 | |

| Regional/rural/remote | 416 | 24.2 | |

| State of residence (missing: n = 19) | |||

| Australian Capital Territory | 62 | 3.6 | |

| New South Wales | 314 | 18.2 | |

| Northern Territory | 14 | 0.8 | |

| Queensland | 154 | 8.9 | |

| South Australia | 128 | 7.4 | |

| Tasmania | 72 | 4.2 | |

| Victoria | 839 | 48.6 | |

| Western Australia | 143 | 8.3 | |

| Sexual activity H (missing: n = 54) | |||

| Never sexually active | 112 | 6.6 | |

| Ever sexually active | 1570 | 92.8 | |

| I don’t remember | 1 | 0.1 | |

| Prefer not to say | 8 | 0.5 | |

| Vaginal sex I (missing: n = 9) | |||

| Never engaged in penis-in-vagina sex | 52 | 3.3 | |

| Ever engaged in penis-in-vagina sex | 1509 | 96.7 | |

| Recent penis-in-vagina sexual activity J (missing: n = 5) | |||

| No recent penis-in-vagina sexual activity | 496 | 33.0 | |

| Recent penis-in-vagina sexual activity | 998 | 66.4 | |

| I don’t remember | 7 | 0.5 | |

| Prefer not to say | 3 | 0.2 | |

Participants were not required to answer all questions. The number of respondents for a given characteristic will not add up to the total number of survey respondents if participants chose not to complete that item. Percentages might not add to 100% because of rounding.

Past and current contraceptive use

A total of 1676 (96%) participants reported ever use of a contraceptive method. Most reported a history of male condom use (n = 1406, 83.9%) or oral contraceptive pill use (1402, 83.7%), with fewer indicating ever using a hormonal IUD (n = 429, 25.6%) or contraceptive implant (n = 429, 25.6%). In total, 1263 respondents indicated currently using contraception, most commonly the male condom (n = 448, 35.5%), oral contraceptive pill (n = 347, 27.5%) or hormonal IUD (266, 21.1%, see Table S1).

Important information to know prior to LARC use

Overall, 1601 participants responded to the question about important information prior to LARC use. Overwhelmingly, 97% (n = 1553) said that the most important information they wanted to know was potential side effects, 91% (n = 1454) wanted to know signs that something is wrong, 90% (n = 1439) wanted to know about effectiveness, 87% (n = 1392) wanted to know about cost, 82% (n = 1308) wanted to know how and where to access the method and 81% (n = 1303) wanted to know the experiences of other people who have used the method (Fig. 1).

Sources of contraceptive information

A total of 1591 participants responded to the question ‘where do you usually get information about contraception?’. Healthcare providers were by far the usual source of contraceptive information, with 86.3% (n = 1373) of participants reporting this. However, 78% (n = 1242) said they turn to the internet, and 15% (n = 247) said they use social media. Although most reported using reputable websites, some reported using news articles, YouTube videos and blogs, while Instagram, Facebook and TikTok were popular social media sites (Table 2). More than half of participants said they turn to their social networks for information, including their friends (n = 910, 57%) and their mothers/female carers (n = 171, 11%). Of the 1568 participants who reported their preferred source of contraceptive information (‘where would you like to get information about contraception?’), participants reported their healthcare provider (n = 1466, 93%), the internet (n = 1015, 64.7%), friends (n = 668, 42%) and social media (n = 305, 20%). Interestingly, 36% (n = 561/1568) of participants indicated a pharmacist as a preferred source of contraceptive information, although only 10% (n = 156/1591) reported that this was their usual source of contraceptive information (Table 2).

| Sources of information | Usual | Preferred | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Total respondents | n = 1591 A | n = 1568 A | |||

| Friends | 910 | 57.2 | 668 | 42.6 | |

| Siblings | 117 | 7.4 | 99 | 6.3 | |

| Mother/female carer | 171 | 10.7 | 329 | 13.9 | |

| Father/male carer | 3 | 0.2 | 29 | 1.8 | |

| Healthcare professional | 1373 | 86.3 | 1466 | 93.5 | |

| Pharmacist | 156 | 9.8 | 561 | 35.8 | |

| Sexual/romantic partners | 105 | 6.6 | 131 | 8.4 | |

| Internet B | 1242 | 78.1 | 1015 | 64.7 | |

| Organisations such as family planning or sexual health clinics | 1063 | 85.7 | – | – | |

| Government websites | 1080 | 87.1 | – | – | |

| News articles | 238 | 19.2 | – | – | |

| YouTube videos | 132 | 10.6 | – | – | |

| Blogs | 107 | 8.6 | – | – | |

| Academic journals | 443 | 35.7 | – | – | |

| Somewhere else | 62 | 5.0 | – | – | |

| Mass media | 96 | 6.0 | 229 | 14.6 | |

| Social media C | 247 | 15.5 | 304 | 19.5 | |

| 121 | 49.2 | – | – | ||

| 148 | 60.2 | – | – | ||

| TikTok | 118 | 48.0 | – | – | |

| Snapchat | 4 | 1.6 | – | – | |

| 57 | 23.2 | – | – | ||

| X (formerly Twitter) | 27 | 11.0 | – | – | |

| Somewhere else | 10 | 4.1 | – | – | |

| Other sources of information not elsewhere specified | 102 | 6.4 | 64 | 4.1 | |

When asked who participants trust to provide accurate contraceptive information (‘Who do you trust to provide you with accurate information about contraception?’), participants reported trusting healthcare providers (including a doctor or a nurse), pharmacists and web pages from healthcare organisations. Despite turning to friends for advice, participants indicated that they only trust friends to provide accurate information a little, and few indicated trust in the information provided on social media (Fig. 2).

Discussion

This study identified the information needs of Australian women considering their contraceptive options, including LARC, and the preferred sources of this information. We found that the most important information women wanted about LARC was about potential side effects, signs that something is wrong and when to seek help, effectiveness and cost. Although we found that healthcare providers were both the usual and preferred source of contraceptive information, the internet, including social media, was also used by many, despite participants indicating less or no trust in these sources of information.

Access to the internet has become almost universal in Australia, with most of the population regularly having access17 (although access issues due to rurality and literacy continue to affect parts of the population18). The internet, including social media, is a key source of contraceptive information;19 however, the information currently available regarding LARC is not always evidence based, can be misleading20 or dangerous21 and, vitally, does not meet the needs of consumers.22 Online information about the oral contraceptive pill has been shown by researchers in Canada to be variable and lacking key information,23 and this deficit is even more pronounced for LARC.20 For example, in our study, we found that potential side effects, signs something is wrong and effectiveness are important pieces of information that women want about LARC; however, in a recent scoping review that examined information on publicly available websites to Australian women about LARC, few consistently provided this information.20 Despite this, research both in Australia and internationally has demonstrated not only that information provided online, including on social media, is acceptable to women,24,25 but that high-quality information provided online can actually increase contraceptive uptake.10 Further research to examine the sorts of information available on social media and the ways in which consumers use this information is urgently needed.

Despite many using the internet to seek contraceptive information, most participants in our study indicated that healthcare providers are not only their preferred source of contraceptive information, but also a trusted source of contraceptive information. We did not examine whether participants actually received their preferred information about LARC from these sources. Although it is encouraging that our participants valued the information provided by their healthcare providers, there are known barriers for healthcare provders’ provision of information about LARC, including their own lack of knowledge about these methods.7,26 Structural barriers may also affect healthcare providers’ ability to provide information to patients about LARC, including difficulty accessing insertion and removal training, no pathways for referral to a clinician who can insert LARC (if the provider is not trained to do it themselves) and insufficient reimbursement for the provision of these contraceptive devices.7 Utilising other healthcare professionals to provide information about LARC, including, for example, pharmacists, may be one avenue for addressing some of these challenges. In our study, participants indicated that a pharmacist is a trusted and preferred source of contraceptive information but not the usual source of contraceptive information. These findings provide additional support for ongoing work exploring the potential role of pharmacists in the provision of contraceptive information.27

Our findings have practical implications. Healthcare providers who provide contraception counselling should include information to consumers about side effects, signs something is wrong, efficacy, cost, and how and where to access these devices. This should also be considered by those who provide information online about LARC. Given many participants use the internet to seek information about LARC, healthcare providers should consider directing patients to reputable websites on which they will be provided with comprehensive and accurate information.

Our findings should be considered within their limitations. Our participants were recruited largely via social media and are a convenience sample. Although we were able to recruit more than 1700 women, our findings are limited by generalisability and selection bias. For example, our sample is largely comprised of university-educated, heterosexual women identifying as Australian who use social media; the information needs of women not born in Australia, with lower levels of educational attainment or who may have low or no English literacy are unlikely to be represented. Indeed, although 24% of our sample lived in rural/remote areas (and is comparable to the 28% of the Australian population living in rural areas), 71% of our sample had a university degree, compared with 36% of the general Australian female population.28 Moreover, a large portion of our sample were current or previous LARC users; their information needs may be affected by their experience using these methods and may be different to those people who have never used LARC. However, this work provides insight into the information needs of those considering LARC as well as the sources through which women seek this information.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that women considering using LARC have clear information needs, including potential side effects, signs that something is wrong and when to seek help, effectiveness and cost. It is vital that these needs are met to support informed decision making. Although healthcare providers are a preferred and trusted source of information about contraception, the internet, including social media, was also a key source of contraceptive information; ensuring the information available here is medically accurate and meeting the needs of consumers is vital.

Data availability

Due to the sensitive nature of the questions asked in this study, survey respondents were assured raw data would remain confidential and would not be shared. Data not available/the data that have been used are confidential. Please contact the researchers for a copy of the survey instrument.

Conflicts of interest

JC is an Associate Editor for Sexual Health but was not involved in the peer review or decision-making process for this paper. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of funding

This project was funded a University of Melbourne Early Career Researcher Grant to Dr Jacqueline Coombe (ID: 2022ECR097).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the people who completed our survey. We also wish to extend our thanks to Associate Professor Fabian Kong for his invaluable suggestions on earlier versions of this manuscript.

References

1 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). National, state and territory population. 2023. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/national-state-and-territory-population/dec-2023 [cited 4 July 2024]

2 Richters J, Fitzadam S, Yeung A, Caruana T, Rissel C, Simpson JM, et al. Contraceptive practices among women: the second Australian study of health and relationships. Contraception 2016; 94(5): 548-55.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

3 Skiba MA, Islam RM, Bell RJ, Davis SR. Hormonal contraceptive use in Australian women: who is using what? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2019; 59(5): 717-24.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

4 Grzeskowiak LE, Calabretto H, Amos N, Mazza D, Ilomaki J. Changes in use of hormonal long-acting reversible contraceptive methods in Australia between 2006 and 2018: a population-based study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2020; 61(1): 128-34.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

5 Bahamondes L, Fernandes A, Monteiro I, Bahamondes MV. Long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARCs) methods. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2020; 66: 28-40.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

6 Pearson S, Boerma C, McNamee K, Bateson D. Long-acting reversible contraceptives: new evidence to support clinical practice. Aust J Gen Pract 2022; 51(4): 246-52.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

7 Mazza D, Bateson D, Frearson M, Goldstone P, Kovacs G, Baber R. Current barriers and potential strategies to increase the use of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) to reduce the rate of unintended pregnancies in Australia: an expert roundtable discussion. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2017; 57(2): 206-12.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

8 Mazza D, Watson CJ, Taft A, Lucke J, McGeechan K, Haas M, et al. Increasing long-acting reversible contraceptives: the Australian Contraceptive ChOice pRoject (ACCORd) cluster randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020; 222(4S): S921.e1-e13.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

9 Garrett CC, Keogh LA, Kavanagh A, Tomnay J, Hocking JS. Understanding the low uptake of long-acting reversible contraception by young women in Australia: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health 2015; 15(72):.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

10 Mazza D, Buckingham P, McCarthy E, Enticott J. Can an online educational video broaden young women’s contraceptive choice? Outcomes of the PREFER pre-post intervention study. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2022; 48(4): 267-74.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

11 RANZCOG. Clinical guideline C-Gyn 3 contraception. 2024. Available at https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/Contraception-Clinical-Guideline.pdf

12 Coombe J, Harris ML, Loxton D. What qualities of long-acting reversible contraception do women perceive as desirable or undesirable? A systematic review. Sex Health 2016; 13(5): 404-19.

| Google Scholar |

13 Coombe J, Harris ML, Loxton D. Examining long-acting reversible contraception non-use among Australian women in their 20s: findings from a qualitative study. Cult Health Sex 2019; 21(7): 822-36.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

14 Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res 2004; 6(3): e34.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

15 Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med 2007; 4(10): e296.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

16 Coombe J, Bittleston H, Ludwick T, Lim MSC, Cardwell ET, Stewart L, et al. Recruiting participants via social media for sexual and reproductive health research. Sex Health 2025; 22(4): SH24123.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

17 The World Bank. Individuals using the Internet (% of population) – Australia. 2023. Available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?locations=AU

19 Claringbold L, Sanci L, Temple-Smith M. Factors influencing young women’s contraceptive choices. Aust J Gen Pract 2019; 48(6): 389-94.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

20 Caddy C, Coombe J. Googling long-acting reversible contraception: a scoping review examining the information available online about intrauterine devices and contraceptive implants. Health Promot J Austr 2024; 35(3): 588-95.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

21 Sexual Health Victoria. TikTok a bad influence when it comes to Contraception. Melbourne: Sexual Health Victoria; 2021. Available at https://shvic.org.au/media [cited 2 March 2023]

22 Coombe J, Caddy C, Camacho X, Koye D. Does the information available about long-acting reversible contraception meet the needs of potential and current users? A mixed-methods study (Oral presentation). In: Australasian Sexual and Reproductive Health Conference. 18–20 September, Sydney, Australia; 2023. Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis & Sexual Health Medicine (ASHM).

23 Marcinkow A, Parkhomchik P, Schmode A, Yuksel N. The quality of information on combined oral contraceptives available on the internet. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2019; 41(11): 1599-607.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

24 Stephenson J, Bailey JV, Blandford A, Brima N, Copas A, D’Souza P, et al. An interactive website to aid young women’s choice of contraception: feasibility and efficacy RCT. Health Technol Assess 2020; 24: 56 1-44.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

25 Caddy C, Cheong M, Lim MSC, Power R, Vogel JP, Bradfield Z, et al. “Tell us what’s going on”: exploring the information needs of pregnant and post-partum women in Australia during the pandemic with ‘Tweets’, ‘Threads’, and women’s views. PLoS ONE 2023; 18(1): e0279990.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

26 Black K, Lotke P, Buhling KJ, Zite NB. A review of barriers and myths preventing the more widespread use of intrauterine contraception in nulliparous women. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2012; 17(5): 340-50.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

27 Buckingham P, Amos N, Hussainy SY, Mazza D. Pharmacy-based initiatives to reduce unintended pregnancies: a scoping review. Res Social Adm Pharm 2021; 17(10): 1673-84.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

28 Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Population. 2023. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population [cited 4 July 2024]