Indigenous and cross-cultural wildlife research in Australia: editorial

Jack Pascoe A * , Marlee Hutton B , Sarah Legge

A * , Marlee Hutton B , Sarah Legge  C D , Emilie Ens E , Hannah Cliff F and Stephen van Leeuwen G

C D , Emilie Ens E , Hannah Cliff F and Stephen van Leeuwen G

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

Abstract

This special collection of Wildlife Research focuses on the importance of Indigenous inclusion and leadership in the stewardship of Australian ecosystems. It highlights the urgent need for collaborations in conservation to address the declining health of our environment and the limitations of historical and current approaches to land management. The issue emphasises that Indigenous Australians hold unique, deep, spiritual and kinship connections to Country steeped in millennia of experience and experimentation, making their voices crucial in shaping the future of environmental management. The collection outlines three key themes. (1) Putting Country first: Indigenous priorities are central to wildlife research and management, prioritising culturally significant entities (CSEs) that hold immense cultural, symbolic, and spiritual value for Indigenous Australians. (2) Opportunities for researchers working on Country: collaboration with Indigenous Australians offers significant opportunities for researchers to learn from Indigenous deep knowledge of the land, enhance research effectiveness, and embrace a more holistic perspective of ecosystems. (3) Respect and reciprocity: successful partnerships with Indigenous Australians are based on respect for culture, cultural obligations to care for Country, Traditional Ecological Knowledge, and community aspirations. This includes adhering to principles of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), safeguarding Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP), and ensuring fair representation in authorship and benefit sharing. The issue emphasises the vital role that Indigenous knowledge and perspectives play in achieving sustainable and culturally appropriate solutions for managing Australia’s natural environment.

Keywords: biocultural conservation, culturally significant entities, free prior and informed consent, Indigenous cultural intellectual property, Indigenous Estate, Indigenous knowledge, Indigenous Rangers, Indigenous self-determination.

Introduction

The ‘Indigenous and cross-cultural wildlife research in Australia’ collection of Wildlife Research comes at a time when the health of Australian ecosystems is seriously and increasingly compromised, and biodiversity is in freefall (Cresswell et al. 2021). Current approaches to land management and conservation have failed to address this decline and the underlying policy and legal framework is inadequate to the task (Wintle et al. 2019; Dielenberg et al. 2023; Legge et al. 2023). As a society, we need to stem biodiversity losses for many reasons, including to maintain the ecosystem services that we all depend on, to safeguard biodiversity for future generations, and because species have their own rights to exist. In addition, and importantly, biodiversity is inherently an element of Country, and for Indigenous Australians, Country is culture, family and self (Rose et al. 2002; Reynolds and Cameron 2025). To drive the required changes to Australia’s relationship with the natural environment, the relational voice of Country must be heard (e.g. Country et al. 2016). As Indigenous Australians, and close colleagues of Indigenous Australians, we recognise that the spiritual and kinship relations between Indigenous Peoples and Country positions them to give Country and species a voice, as demonstrated by Country et al. (2016), Raven et al. (2021) for emus, and Pascoe et al. (2024a) for whales.

Prevailing rhetoric about contemporary Indigenous issues is dominated by comparative disparities in health and economic inequity (‘Closing the Gap’); however, these narratives fail to acknowledge that Indigenous People are Country. Without broader recognition and active support of the deep spiritual connection between Indigenous Peoples and Country that is afforded by free access to and interaction with Country, commentary of Indigenous issues is easily reduced to one of social disadvantage and dispossession. Recent research aims to shift this narrative and raise awareness about Indigenous identified measures of happiness that are embedded in access and connection to Country and ancestral knowledge (Cairney et al. 2017). Further, incorporation of Indigenous knowledge, priorities and cultural values in measures of conservation success can also leverage new funding streams, such as from emerging carbon and biodiversity conservation ‘markets’ (see Smuskowitz et al. 2025). These measures focus on a Country and relational strengths-based approach that may feed into socio-economic benefits and, therefore, indirectly address Closing the Gap targets.

Indigenous inclusion in the stewardship of Country is imperative for the continuation of Indigenous cultures, languages, knowledges and ecosystems themselves (Reynolds and Cameron 2025), as articulated through recent global advocacy of linked biocultural diversity (and conservation) (Maffi 2001; Sterling et al. 2017; Rozzi 2018; Ens et al. 2023). Further, recognition of the intimate links between cultural and environmental diversity is entwined in human rights and environmental policy and Australia’s international commitments under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the Convention on Biological Diversity including the Nagoya Protocol. Inclusion of Traditional Knowledge is also crucial to the health of Country, and to effectively mitigate the pervasive threats driving the decline of ecosystem health around the continent, we desperately need to adopt ‘new’ approaches. The articles in this collection highlight that these ‘new’ approaches to wildlife research and management are coming in the form of programs informed by contemporary expressions of the ancient ancestral knowledge and wisdom of Indigenous Australians in partnership with collaborators who seek to engage in the ‘right way’ (Goolmeer and van Leeuwen 2023). For example, remote-sensing technologies are allowing more cost effective and rapid detection of invasive and native species and assessment of vegetation (e.g. Geyle et al. 2024; Legge et al. 2024a; Moore et al. 2024; Ngururrpa Rangers et al. 2024; Lavery et al. 2025; Paltridge et al. 2025).

In this collection, the following three themes emerge across the papers: (1) putting Country stewardship first by promoting Indigenous priorities; (2) opportunities and benefits for wildlife research that come from working on Country in partnership with Indigenous Australians; and (3) the need for research partnerships with Indigenous Australians that prioritise respect and equity in benefit sharing.

Putting Country first

For Indigenous Australians, Country provides everything, including rock, soil, water, materials, foods, medicines, totems; it sustains people mentally, physically and spiritually; it teaches and maintains lore and law, and binds individuals and groups through responsibility and obligation to Country and kin (Pascoe et al. 2024a; Reynolds and Cameron 2025). Indigenous Australians are therefore asserting that Country is placed at the centre of what we do in wildlife research and management (Goolmeer et al. 2022a, 2022b; Shields et al. 2024). This has led to an increase in research that looks to place Indigenous priorities at the forefront of the ongoing stewardship of Country (Ens and Turpin 2022; Campbell et al. 2024).

Culturally significant entities (CSE) refer to species and ecosystems of resource, cultural, symbolic or spiritual value for Indigenous Peoples (Goolmeer et al. 2022a). CSEs are becoming increasingly recognised for their application in policy, and as biocultural indicators that reflect the way Indigenous Australians express their obligations as stewards of Country (Goolmeer et al. 2024). We are seeing this recognition in demands for rights-based approaches to conservation management, that promote the ongoing stewardship of Country through relationality, connection with, and responsibility to CSEs and Country (Hill et al. 2021; Poelina et al. 2023). The collection includes examples of Indigenous Australians who are using CSEs to shape the on-ground management of their estates and to frame their entire approach to biocultural land care (Campbell et al. 2024; Pascoe et al. 2024a, 2024b), and enduring economic potential (Smuskowitz et al. 2025).

This approach to the stewardship of Country is radically different from the relationship with the environment of contemporary non-Indigenous culture in Australia. For example, non-Indigenous conservation often focuses on threatened or declining species and threat abatement, whereas Indigenous conservation centres on place-based approaches that address all interconnections between biophysical, cultural and spiritual aspects of Country. In practice, this can mean a focus on culturally significant species that are not considered threatened but instead are common (e.g. see Campbell et al. 2024; Goolmeer et al. 2024). Indigenous approaches are more holistic and do not draw distinctions between people and the land, offering the potential to enrich our society with deeper understanding of our relationships and responsibilities to Country (Kwaymullina 2005).

Opportunities for researchers working on Country

The opportunities for working on Country with Indigenous Australians in wildlife research and management are significant, especially given the increasing recognition of Indigenous land rights and designation of Indigenous Protected Areas (Goolmeer et al. 2022b). The relationships of Indigenous Australians with Country are intensely and inherently place-based. Indigenous Rangers and Knowledge Holders know their Country, have extraordinary observational skills, are regularly out on Country, and are often early to detect changes as they are attuned to patterns in the landscape and in biodiversity. In collaborations with ‘outsider’ or ‘insider’ researchers (see Tuhiwai Smith 2012; Cooke et al. 2022), this ‘local’ knowledge can improve the effectiveness of surveys, monitoring and subsequent management actions designed to mitigate threats, as clearly shown by the lizard research of Ward-Fear et al. (2019). Many papers in this special issue also attest to this, including research collaborations to enhance conservation management of white-throated grasswrens in Arnhem Land (Dixon et al. 2024); night parrots on Ngururrpa Country in the Great Sandy Desert (Ngururrpa Rangers et al. 2024); looking after wiliji or black-flanked rock-wallabies by Nyikina Mangala in the west Kimberley (Lavery et al. 2025); monitoring of warru or black-flanked rock-wallaby on Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (Read et al. 2025) and bilbies on the Dampier Peninsula and in the Tanami Desert (Geyle et al. 2024; Moore et al. 2024).

Researchers have much to learn by looking at Country with Indigenous eyes (Reynolds and Cameron 2025). More holistic local Indigenous perspectives about how species fit in ecosystems (e.g. dingoes on Nyangumarta Country, Smith et al. 2024) extend also to the place of people in ecosystems, and how human interactions with their environment can sustain ecological states. A good example of this is the influence of people on fire regimes and the persistence of threatened species in the Kiwirrkurra Indigenous Protected Area (Paltridge et al. 2025).

By embracing local Indigenous perspectives, research partnerships can combine spiritual, cultural and emotional restoration in tandem with ecological restoration. Such biocultural restoration (see Maffi 2001) can entwine tangible actions of caring for Country with aims that re-connect people with Country and bring peace for Indigenous landowners, even after large-scale events, such as the 2019–20 wildfires that affected Australia’s southern and eastern forests (Williamson 2022; Pascoe et al. 2023). Lloyd et al. (2024) described a collaboration between researchers and Indigenous people, in which traditional weaving techniques were adapted to create roost shelters for golden-haired bats in severely burnt forests of the Gumbaynggirr Nation. In another example, Moro et al. (2024) showed how animal translocations that aimed to restore species in areas where they had become locally extinct were also valuable opportunities to rekindle cultural knowledge and practice and heal across many dimensions.

The Indigenous Estate (all land and sea Country over which Indigenous Australians have rights to undertake customary and traditional activities as conferred through the Crown) covers more than half of Australia’s landmass and incorporates vast tracts of Country with high conservation priority (Jacobsen et al. 2020). In addition, Indigenous Rangers also work on other tenures such as government-run National Parks, sometimes in a co-management arrangement (Hill et al. 2012). Consequently, collaborations among multiple Indigenous groups, and between those groups and researchers, have the potential to cover very large areas, undertaking research and monitoring that benefit from scale. Such large-scale collaborations are leading to extraordinary insights into the distributions of native and invasive species across entire biomes, as demonstrated by several papers in this collection (Legge et al. 2024b; Lindsay et al. 2024).

The papers in this collection underscore the growing leadership of Indigenous Australians in wildlife research. This includes demonstrating the conservation outcomes of traditional practice, such as burning practices in the desert (e.g. Paltridge et al. 2025), as well as utilising scientific method to generate new knowledge that can be applied to revise and adapt the care of Country, such as understanding how modifying fire patterns and contemporary fire management could change faunal communities in the desert (e.g. Legge et al. 2024a).

Respect and reciprocity

The interconnected cultures of Indigenous Australians engender a network of respectful and reciprocal relationships that underpin obligations and responsibilities to everything in Country. For non-Indigenous Australians seeking to work on Country, it is important to understand where they stand within this context and be prepared to enter reciprocal relationality with Country and its Traditional Custodians. This understanding can come only from ample time spent on-Country with Indigenous Australians and their communities. Partnerships with Indigenous Australians unquestionably represent opportunities for wildlife research, but Indigenous Australians are demanding more from research partners (Weir et al. 2024) to meet their expectation of reciprocity and mutual benefit sharing. More than just utilisation of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and the Indigenous Estate, it is important that research benefits and respects Indigenous Australians and addresses the aspirations and obligations of Indigenous Australians, including their agency in decisions about them and their Country that may not always be obviously connected with the wildlife or species that researchers want to study. Hence, we recommend that researchers spend time with Indigenous Australians to understand what they want from research partnerships and that this is factored into budgets and plans, whether they be short or long term.

In respecting Indigenous Australian and TEK, it is essential to understand and follow the principles of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) and to ensure that arrangements are in place to protect any Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) that is shared by Knowledge Holders (Janke 2019; Woodward et al. 2020). So as to balance open science principles and Indigenous data sovereignty when working with TEK, leveraging collective benefit, authority to control, responsibility and ethics (CARE), findable, accessible, interoperable, and reproduceable (FAIR) and transparency, responsibility, user focus, sustainability and technology (TRUST) principles is imperative across the data lifecycle, whether it be for knowledge generated from new research and on-Country partnerships, existing knowledge collected, collated and synthesised from contemporary sources or knowledge repatriated back to Indigenous Australians from archival repositories (Carroll et al. 2021; Jennings et al. 2025).

In science, authorship on publications is critical for establishing intellectual leadership in the production of the paper; it is imperative that authorship of collaborative works is defined by and agreed to by Indigenous partners. This collection of papers demonstrates multiple ways of achieving and acknowledging Indigenous research contributions, from research led or directed by Indigenous scholars (e.g. Ngururrpa Rangers et al. 2024; Pascoe et al. 2024a, 2024b; Reynolds and Cameron 2025) to Indigenous partners being acknowledged individually and collectively. This collection also addresses critiques of science for prior and continuing systemic racism (Nature Editorial 2020) by providing an opportunity for Indigenous and cross-cultural research to be published and be accessible for present and future generations. Along with other special issues featuring Indigenous and cross-cultural work (e.g. Ecological Management & Restoration Special Issues: ‘Indigenous and cross-cultural ecology – perspectives from Australia’ in 2022, see Ens and Turpin 2022; and ‘Remote Indigenous Land and Sea Management’ in 2012, see Ens and McDonald 2012), these publications make substantial contributions to promotion of Indigenous themes in conservation science generally, and wildlife research more specifically.

When working with Indigenous Australians, including Ranger groups, it is important to understand the many various competing priorities that are constantly being balanced. Organisations and individuals are often stretched, working on limited budgets and dealing with many competing demands from community. To ensure that Rangers and Knowledge Holders have opportunities to engage and participate in fauna conservation and research, it is essential to ensure that partners can provide appropriate timeframes, resources and flexibility to allow for this. Correspondingly, effective and respectful engagement can, depending on the scale of the project, require significant investment of by researchers, which should be taken into account during project planning (Ens and McDonald 2012).

Partners working with Indigenous Australians should also be considering opportunities for professional development of Indigenous co-researchers and their communities. This can come in the form of higher education opportunities (e.g. the Bush University model, Jaggi et al. 2024), training in skills useful in research and monitoring, or professional development in communicating with diverse audiences (see Ens and Turpin 2022). However, researchers need to understand that there are many interpretations of what professional development means, and Indigenous priorities and aspirations should be respected. Opportunities for development seen through the contemporary science lens may sometimes be what their Indigenous colleagues seek, but in other cases, these priorities could be quite different. Whereas a university-based researcher might value the chance to acquire some new analytical skills or secure a field vehicle, an Indigenous Ranger may also value that chance, or they may alternatively prefer opportunities to spend time with Elders and community on Country outside of the formal research tasks, allowing space and time for intergenerational transfer of Indigenous knowledge and practice (see Smuskowitz et al. 2025).

Conclusions

Country, to me, means us. Its where we come from. Country is Mother Earth, and all living things comes from Mother Earth in its entirety. So, if you talk about wildlife, then you classify us as we are a part of it. We are its original inhabitants, and we have a responsibility to look after Country and care for it. By protecting and respecting the spiritual foundations of Country we can restore our animals, plants, and people, heal our families and Law, and our cultural places. [Reynolds and Cameron 2025, p. 3]

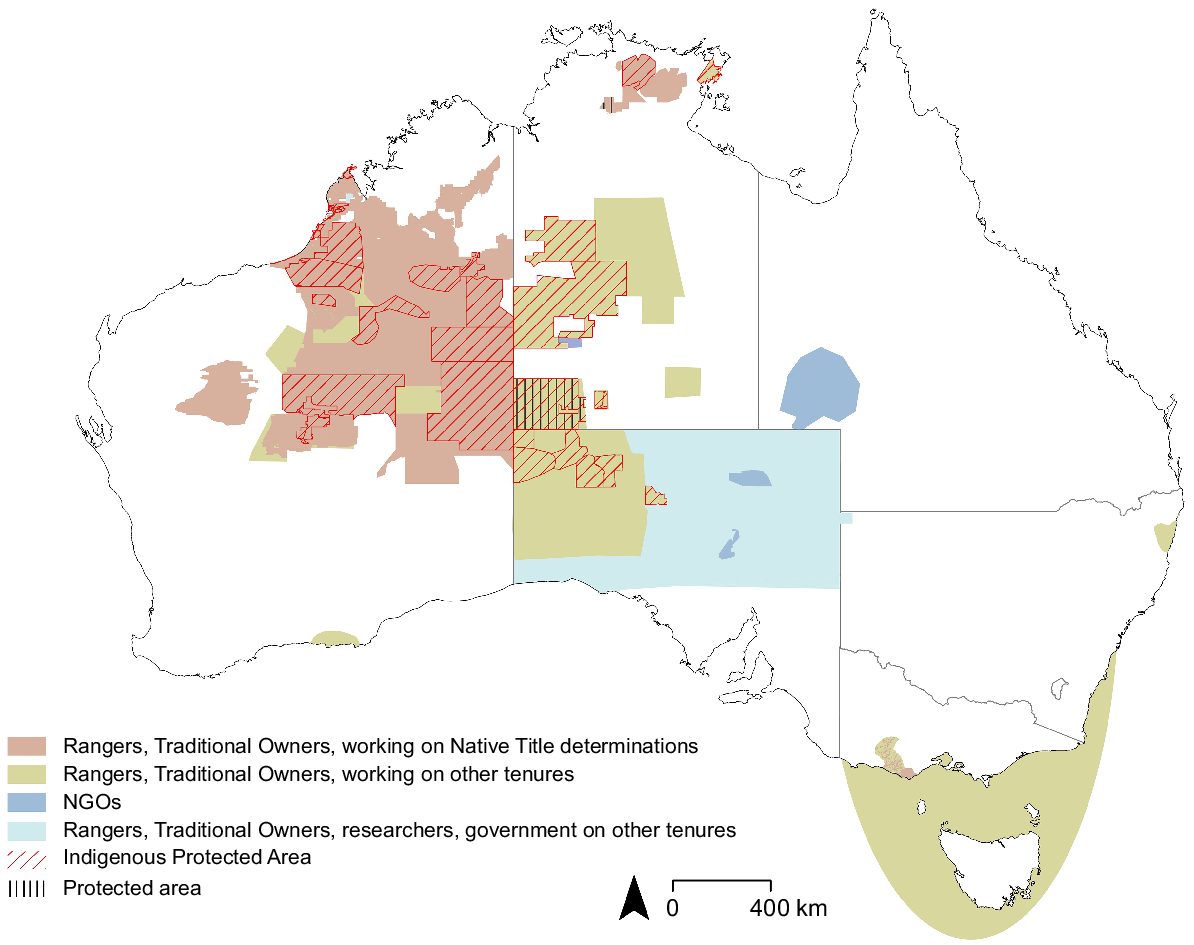

The opportunity for wildlife research and researchers to engage with Indigenous Australians on Country is well demonstrated in this collection of papers, which features work from across Australia (Fig. 1). The collection also highlights the benefits, challenges and recommendations for respectful, inclusive and reciprocal relationships between researchers and Indigenous Australians. And finally, it presents a suite of tangible projects that champion the priorities of Indigenous Australians in wildlife research and management for the stewardship of their Country, guiding the way for future projects to continue to empower Indigenous leadership in science and decolonise prevailing Western conservation approaches.

Map showing areas, with some information on their tenures, that feature in research that is presented in the collection. Spatial data visible on the map are sourced from the National Native Title Tribunal (see https://www.nntt.gov.au/assistance/Geospatial/Pages/Spatial-aata.aspx); the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (see https://doi.org/10.25814/cfm3-db86) and from the Commonwealth of Australia’s spatial data portal (see https://fed.dcceew.gov.au/).

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were generated or analysed during this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors are Guest Editors of the ‘Indigenous and cross-cultural wildlife research in Australia’ collection in Wildlife Research, and J. Pascoe is an Associate Editor and S. Legge is an Editor-in-Chief for Wildlife Research. To mitigate potential conflicts of interest, the authors had no editor-level access to this manuscript during peer review. The authors have no further conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Elders who have passed on the wisdom of our Old People and Country to Indigenous Australians across the Country and who continue to generously share with all Australians.

References

Cairney S, Abbott T, Quinn S, Yamaguchi J, Wilson B, Wakerman J (2017) Interplay wellbeing framework: a collaborative methodology ‘bringing together stories and numbers’ to quantify Aboriginal cultural values in remote Australia. International Journal for Equity in Health 16(1), 68.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Campbell B, Russell S, Brennan G, Condon B, Gumana Y, Morphy F, Ens E (2024) Prioritising animals for Yirralka Ranger management and research collaborations in the Laynhapuy Indigenous Protected Area, northern Australia. Wildlife Research 51, WR24071.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Carroll SR, Herczog E, Hudson M, Russell K, Stall S (2021) Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR principles for Indigenous data futures. Scientific Data 8(1), 108.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Cooke P, Fahey M, Ens EJ, Raven M, Clarke PA, Rossetto M, Turpin G (2022) Applying First Nations and State biocultural research protocols in ecology: insider and outsider experiences from Australia. Ecological Management & Restoration 23(S1), 64-74.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Country B, Wright S, Suchet-Pearson S, Lloyd K, Burarrwanga L, Ganambarr R, Ganambarr-Stubbs M, Ganambarr B, Maymuru D, Sweeney J (2016) Co-becoming Bawaka: towards a relational understanding of place/space. Progress in Human Geography 40(4), 455-475.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dielenberg J, Bekessy S, Cumming GS, Dean AJ, Fitzsimons JA, Garnett S, Goolmeer T, Hughes L, Kingsford RT, Legge S, Lindenmayer DB, Lovelock CE, Lowry R, Maron M, Marsh J, McDonald J, Mitchell NJ, Moggridge BJ, Morgain R, O’Connor PJ, Pascoe J, Pecl GT, Possinghma H, Ritchie EG, Smith LDG, Spindler R, Thompson RM, Treziae J, Umbers K, Woinarski J, Wintle BA (2023) Australia’s biodiversity crisis and the need for the biodiversity council. Ecological Management & Restoration 24(2–3), 69-74.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Dixon KM, von Takach B, Hayward-Brown B, Guymala T, Warddeken Rangers, Jawoyn Rangers, Djurrubu Rangers, Mimal Rangers, Evans J, Penton CE (2024) Integrating western and Indigenous knowledge to identify habitat suitability and survey for the white-throated grasswren (Amytornis woodwardi) in the Arnhem Plateau, Northern Territory, Australia. Wildlife Research 51(9), WR24034.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ens EJ, McDonald T (2012) Caring for country: Australian natural and cultural resource management. Ecological Management & Restoration 13(1), 1.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ens EJ, Turpin G (2022) Synthesis of Australian cross-cultural ecology featuring a decade of annual Indigenous ecological knowledge symposia at the ecological society of Australia conferences. Ecological Management & Restoration 23(S1), 3-16.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ens EJ, Rossetto M, Costello O (2023) Recognising Indigenous plant-use histories for inclusive biocultural restoration. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 38(10), 896-898.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Geyle HM, Schlesinger C, Banks S, Dixon K, Murphy BP, Paltridge R, Doolan L, Herbert M, North Tanami Rangers, Dickman CR (2024) Unravelling predator–prey interactions in response to planned fire: a case study from the Tanami Desert. Wildlife Research 51, WR24059.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Goolmeer T, van Leeuwen S (2023) Indigenous knowledge is saving our iconic species. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 38(7), 591-594.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Goolmeer T, Skroblin A, Grant C, van Leeuwen C, Archer R, Gore-Birch C, Wintle BA (2022a) Recognizing culturally significant species and Indigenous-led management is key to meeting international biodiversity obligations. Conservation Letters 15(6), e12899.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Goolmeer T, Skroblin A, Wintle BA (2022b) Getting our act together to improve Indigenous leadership and recognition in biodiversity management. Ecological Management & Restoration 23(S1), 33-42.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Goolmeer T, Costello O, Culturally Significant Entities workshop participants, Skroblin A, Rumpff L, Wintle BA (2024) Indigenous-led designation and management of culturally significant species. Nature Ecology & Evolution 8(9), 1623-1631.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hill R, Harkness P, Raisbeck-Brown N, Lyons I, Álvarez-Romero JG, Kim MK, Chungalla D, Wungundin H, Aiken M, Malay J, Williams B, Buissereth R, Cranbell T, Forrest J, Hand M, James R, Jingle E, Knight O, Lennard N, Lennard V, Malay I, Malay L, Midmee W, Morton S, Nulgit C, Riley P, Shadforth I, Bieundurry J, Brooking G, Brooking S, Brumby W, Bulmer V, Cherel V, Clifton A, Cox S, Dawson M, Gore-Birch C, Hill J, Hobbs A, Hobbs D, Juboy C, Juboy P, Kogolo A, Laborde S, Lennard B, Lennard C, Lennard D, Malay N, Malay Z, Marshall D, Marshall H, Millindee L, Mowaljarlai D, Myers A, Nnarda T, Nuggett J, Nulgit L, Nulgit P, Poelina A, Poudrill D, Ross J, Shandley J, Skander R, Skeen S, Smith G, Street M, Thomas P, Wongawol B, Yungabun H, Sunfly A, Cook C, Shaw K, Collard T, Collard Y (2021) Learning together for and with the Martuwarra Fitzroy River. Sustainability Science 17, 351-375.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jaggi A, Rogers KG, Rogers HG, Daniels AY, Ens E, Pinckham S (2024) We need to run our own communities: creating the wuyagiba bush uni in remote Southeast Arnhem Land, Northern Australia. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education 34(1), 122-144.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jennings L, Jones K, Taitingfong R, Martinez A, David-Chavez D, Alegado RA, Tofighi-Niaki A, Maldonado J, Thomas B, Dye D, Weber J, Spellman KV, Ketchum S, Duerr R, Johnson N, Black J, Carroll SR (2025) Governance of Indigenous data in open earth systems science. Nature Communication 16(1), 572.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kwaymullina A (2005) Seeing the light: Aboriginal law, learning and sustainable living in country. Indigenous Law Bulletin 6(11), 12-15.

| Google Scholar |

Lavery TH, Watson DJ, Nyikina Mangala Rangers, Broome L, Charles R, Eldridge MDB, Green J, Gregory P, Legge S, Millindee S, Pearson D, Skeen T, Smuskowitz D, Southwell D, Watson A, Watson A, Watson W, Weigner N, Woinarski J, Woolley L-A, Lindenmayer DB (2025) Monitoring the Endangered wiliji (Petrogale lateralis kimberleyensis) on Nyikina Mangala Country (Western Australia) using camera traps. Wildlife Research 52, WR24081.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Legge S, Rumpff L, Garnett ST, Woinarski JCZ (2023) Loss of terrestrial biodiversity in Australia: magnitude, causation, and response. Science 381(6658), 622-631.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Legge S, Bijlani H, Karajarri Rangers, Ngurrara Rangers, Taylor B, Shovellor J, McCarthy F, Murray C, Ala’i J, Brown C, Tromp K, Bayley S, Noakes E, Wemyss J, Cliff H, Jackett N, Greatwich B, Corey B, Cowan M, Macdonald KJ, Murphy BP, Banks S, Lindsay M (2024a) Pirra Jungku and Pirra Warlu: using traditional fire-practice knowledge and contemporary science to guide fire-management goals for desert animals. Wildlife Research 51(10), WR24069.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Legge S, Indigo N, Southwell DM, Skroblin A, Nou T, Young AR, Dielenberg J, Wilkinson DP, Brizuela-Torres D, Yankunytjatjara AP, Birriliburu Rangers, Backhouse B, Galindez Silva C, Arkinstall C, Lynch C, Central Land Council Rangers, Curnow CL, Rogers DJ, Moore D, Ryan-Colton E, Benshemesh J, Schofield J, Jukurrpa K, Karajarri Rangers, Moseby K, Tuft K, Bellchambers K, Bradley K, Webeck K, Kimberley Land Council Land and Sea Management Unit, Kiwirrkurra Rangers, Tait L, Lindsay M, Dziminski M, Newhaven Warlpiri Rangers, Ngaanyatjarra Council Rangers, Ngurrara Rangers, Jackett N, Nyangumarta Rangers, Nyikina Mangala Rangers, Parna Ngururrpa Aboriginal Corporation, Copley P, Paltridge R, Pedler RD, Southgate R, Brandle R, van Leeuwen S, Partridge T, Newsome TM, Wiluna Martu Rangers, Yawuru Country Managers (2024b) The Arid Zone Monitoring Project: combining Indigenous ecological expertise with scientific data analysis to assess the potential of using sign-based surveys to monitor vertebrates in the Australian deserts. Wildlife Research 51, WR24070.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lindsay M, Paltridge R, Leseberg N, Jackett N, Murphy S, Birriliburu Rangers, Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa, Martu Rangers, Karajarri Rangers, Kiwirrkurra Rangers, Ngurrara Rangers, Nyangumarta Rangers, Wiluna Martu Rangers, Gooniyandi Rangers, Kija Rangers, Paruku Rangers, Nharnuwangga Wajarri Ngarlawangga Warida Rangers, Ngurra Kayanta Rangers, Ngururrpa Rangers, Boyle A, Watson A, Greatwich B, Hamaguchi N, Shipway S (2024) Aboriginal rangers co-lead night parrot conservation: background, survey effort and success in Western Australia 2017–2023. Wildlife Research 51, WR24094.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lloyd A, Scanlon A, Clegg L, Link R, Jarrett L, Pursch K, Williams A, Giese M (2024) Girrimarring wiirrilgal bulany ngayanbading (bat nest-type fur sun-like): blending traditional knowledge and western science to create roosting habitat for the threatened golden-tipped bat Phoniscus papuensis. Wildlife Research 51(11), WR24065.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Moore HA, Yawuru Country Managers, Bardi Jawi Oorany Rangers, Nyul Nyul Rangers, Nykina Mangala Rangers, Gibson LA, Dziminski MA, Radford IJ, Corey B, Bettink K, Carpenter FM, McPhail R, Sonneman T, Greatwich B (2024) Where there’s smoke, there’s cats: long-unburnt habitat is crucial to mitigating the impacts of cats on the Ngarlgumirdi, greater bilby (Macrotis lagotis). Wildlife Research 51, WR23117.

| Google Scholar |

Moro D, West R, Lohr C, Wongawol R, Morgan V (2024) Partnering and engaging with Traditional Owners in conservation translocations. Wildlife Research 51(10), WR24053.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Nature Editorial (2020) Systemic racism: science must listen, learn and change. Nature 582, 147.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Paltridge R, Napangati Y, Ward Y, Nangagee J, James M, Olodoodi R, Napangati N, Eldridge S, Schubert A, Blackwood E, Legge S (2025) The relationship between the presence of people, fire patterns and persistence of two threatened species in the Great Sandy Desert. Wildlife Research 52, WR24076.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pascoe J, Shanks M, Pascoe B, Clarke J, Goolmeer T, Moggridge B, Williamson B, Miller M, Costello O, Fletcher MS (2023) Lighting a pathway: our obligation to culture and Country. Ecological Management & Restoration 24(2–3), 153-155.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pascoe J, Goolmeer T, McKnight A, Couzens V (2024a) Whale are our kin, our memory and our responsibility. Wildlife Research 51, WR23157.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pascoe J, Clarke M, Hickey E, Prentice L, Couzens V, Clarke J (2024b) Pang-ngooteekeeya weeng malangeepa ngeeye (remembering our future: bringing old ideas to the new). Wildlife Research 51(10), WR24068.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Poelina A, Paradies Y, Wooltorton S, Mulligan EL, Guimond L, Jackson-Barrett L, Blaise M (2023) Learning to care for Dangaba. Australian Journal of Environmental Education 39(3), 375-389.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Raven M, Robinson D, Hunter J (2021) The emu: more-than-human and more-than-animal geographies. Antipode 53(5), 1526-1545.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Read JL, West R, Nyaningu G, Rangers W, Oska M, Phillips BL (2025) Adaptive management of a remote threatened-species population on Aboriginal lands. Wildlife Research 52, WR24050.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Reynolds D, Cameron L (2025) Yarning up with Doc Reynolds: an interview about Country from an Indigenous perspective. Wildlife Research 52, WR24104.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Shields T, Talbot L, Pascoe J, Gilbert J, Gould J, Hunter B, van Leeuwen S (2024) Creating an authorizing environment to care for country. Conservation Letters 18, e13075.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Smith BP, Loughridge J, Nyangumarta Rangers, Wright C, Badal A, Rose N, Hunter E, Kalpers J (2024) Traditional owner-led wartaji (dingo) research in Pirra Country (Great Sandy Desert): a case study from the Nyangumarta Warrarn Indigenous Protected Area. Wildlife Research 51, WR24082.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Smuskowitz DG, Ens EJ, Campbell B, Wunuŋmurra BM, Wunuŋmurra B, Waṉambi LG, Wunuŋmurra BB, Marrkula BT, Waṉambi DG, The Yirralka Rangers (2025) Exploring a new biocultural credit assessment framework: case study for Indigenous-led fauna management from the Laynhapuy Indigenous Protected Area, Australia. Wildlife Research 52, WR24022.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sterling EJ, Filardi C, Toomey A, Sigouin A, Betley E, Gazit N, Newell J, Albert S, Alvira D, Bergamini N, Blair M, Boseto D, Burrows K, Bynum N, Caillon S, Caselle JE, Claudet J, Cullman G, Dacks R, Eyzaguirre PB, Gray S, Herrera J, Kenilorea P, Kinney K, Kurashima N, Macey S, Malone C, Mauli S, McCarter J, McMillen H, Pascua P, Pikacha P, Porzecanski AL, de Robert P, Salpeteur M, Sirikolo M, Stege MH, Stege K, Ticktin T, Vave R, Wali A, West P, Winter KB, Jupiter SD (2017) Biocultural approaches to well-being and sustainability indicators across scales. Nature Ecology & Evolution 1(12), 1798-1806.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Ngururrpa Rangers, Sunfly C, Schubert A, Reid AM, Leseberg N, Parker L, Paltridge R (2024) Potential threats and habitat of the night parrot on the Ngururrpa Indigenous Protected Area. Wildlife Research 51, WR24083.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ward-Fear G, Balanggarra Rangers, Pearson D, Bruton M, Shine R (2019) Sharper eyes see shyer lizards: collaboration with indigenous peoples can alter the outcomes of conservation research. Conservation Letters 12(4), e12643.

| Google Scholar |

Weir JK, Morgain R, Moon K, Moggridge B (2024) Centring Indigenous peoples in knowledge exchange research-practice by resetting assumptions, relationships and institutions. Sustainability Science 19, 629-645.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Williamson B (2022) Cultural burning and public forests: convergences and divergences between Aboriginal groups and forest management in south-eastern Australia. Australian Forestry 85(1), 1-5.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wintle BA, Cadenhead NCR, Morgain RA, Legge SM, Bekessy SA, Cantele M, Possingham HP, Watson JEM, Maron M, Keith DA, Garnett ST, Woinarski JCZ, Lindenmayer DB (2019) Spending to save: what will it cost to halt Australia’s extinction crisis? Conservation Letters 12, e12682.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |