Physiotherapy pessary providers in Australia: results of a multidisciplinary survey of practice

Patricia B. Neumann A * , Katrina McEvoy B , Hannah Moger B , Melissa Harris B , Olivia Wright B , Irena Nurkic B , Judith Thompson B and Rebekah Das AA

B

Abstract

Physiotherapists have recently become involved in the management of women with prolapse by providing pessary care as well as pelvic floor muscle training and lifestyle advice. There are little data internationally about physiotherapists providing pessaries and only one Australian study to date reporting on a multidisciplinary survey of pessary providers, which indicated large numbers of physiotherapists involved in pessary management.

The aim of this study was to report specifically on further details of physiotherapy pessary practice from this survey.

An anonymous 24-item electronic survey was developed and sent to all known healthcare pessary providers in Australia between 26 June and 31 August 2022. The survey contained both multiple choice and text answer questions, divided into four sections: clinician demographics, pessary management training, current practices and future training needs. Responses were analysed using descriptive statistics and key variables reported using frequencies (numbers and percentages).

We report comprehensive data on the 324 physiotherapy respondents, who were distributed across all states and territories and in all regions of Australia except in very remote regions. Physiotherapists had 1–15 years’ experience in pessary management, were predominantly employed in private practice, with variable training, and no universal requirement to demonstrate competence. They used a wide range of pessaries, fitted a median of three pessaries per month and all taught pessary self-management.

Physiotherapists are widely distributed across Australia providing local pessary management for women with prolapse. There is a need for national training standards to ensure physiotherapists deliver safe, best-practice pessary care.

Keywords: competency, conservative management, mentoring, multidisciplinary, pelvic health physiotherapist, pelvic organ prolapse, physiotherapy, self-management, scope of practice, survey, training, vaginal support pessary.

Introduction

Pessaries for women with pelvic organ prolapse (POP) have traditionally been prescribed and managed by gynaecologists and urogynaecologists1 and frequently also by nurses.2–4 The first report of physiotherapists in a survey of pessary practice from the United Kingdom (UK) found that only 1.4% of 527 respondents were physiotherapists, while 96.8% were doctors and 1.8% were nurses.5 Few details of the physiotherapy practices were described. Subsequently, physiotherapy pessary providers have been increasingly reported in surveys of practice from the UK6 and France.7

Internationally, little is known about the extent or characteristics of physiotherapists’ involvement in pessary management (PM), their experience as women’s or pelvic health practitioners, their training, or the clinical settings in which they work. Physiotherapists involved in PM will be referred to as pelvic health physiotherapists throughout the article. A recent UK study evaluating the pessary service at one National Health Service (NHS) institution, acknowledged that physiotherapists constituted 15% of the multidisciplinary team providing pessary care but only the outcomes describing the quality of care provided by the medical and nursing team members were reported.8

Growing multidisciplinary involvement in pessary management is potentially important in the context of Australia’s ageing population9 and with up to 50% of parous women over 50 having POP.10 A specialised urogynaecology (UG) service in the UK reported a 225% increase in demand for UG services in the previous year.8 Advanced practice physiotherapy services in Australia have been shown to alleviate pressure on tertiary UG services, reduce waiting times for gynaecology consultations, achieve high patient satisfaction rates,11 and reduce the need for gynaecology reviews.12 Long wait times for gynaecology appointments were found to increase the burden for women with pelvic health conditions, including symptomatic POP.13

A further challenge for Australian women with POP is access to services on a continent with a population of 27 million spread across metropolitan, rural and remote areas. Furthermore, people living in rural areas are known to have poorer health outcomes.14

The Australian healthcare landscape has unique features, combining publicly funded Medicare with a private health system. This contrasts with the UK where health care is predominantly delivered by the NHS. In Australia, pessary management is available for women with POP through Medicare, which provides publicly funded pessary clinics under gynaecology or UG management. However, PM is also available privately from UGs, gynaecologists and physiotherapists, although there are currently limited data to elucidate these services.15

Differences in governance structures also exist between the Australian public and private sectors. Physiotherapists in the public health system are required to meet stringent competency standards, typically co-developed by physiotherapists and medical colleagues.16 By contrast, there are currently no such competency standards for physiotherapists practising privately.15

One key reason for practitioners to demonstrate their competence in PM is the potential to cause harm, e.g. due to the insertion of a foreign body into the vagina, insertion of an incorrect pessary type, or failure to monitor the patient long term.17 Adequate training is therefore needed to acquire the knowledge and skills in the management of different pessaries and to set up fail-safe systems within a clinical environment to mitigate risk.18–20

The first report of pessary training for Australian medical practitioners, nurses and physiotherapists was published in 2015, describing one-day training, which provided no assessment of participants’ competence in fitting or managing pessaries.21 However, these three 1-day workshops in 2010–2012 potentially seeded a growing interest by Australian physiotherapists in adopting PM as part of their conservative approach to prolapse management.

We conducted a national survey of pessary providers in 2022 and subsequently published the results providing the first in-depth description of pessary management in Australia, focusing on the different professions involved.15 The focus of the current paper is to explore the data specific to physiotherapists with a view to describing further details about their management of pessaries, including their geographic location, characteristics of their clinical practice settings and relevant training.

Aims

The aims of this study were therefore firstly to describe the physiotherapists providing PM in Australia in terms of their demographics, background and training and secondly to describe the location and characteristics of their services.

Materials and methods

In this cross-sectional study, an anonymous 24 item electronic survey (Supplementary Appendix 1) was developed and distributed to healthcare practitioners (HCPs) providing PM for POP. Ethical approval was granted by Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (HREC number HRE2022-0325). The methods and details of its development have been previously described in detail.15

The survey was developed by co-investigators with experience in PM using concepts from similar international studies2,4–6,22 and clinical practice guidelines.10,23 Representatives from each target discipline (medical, nursing and physiotherapy) and the Urogynaecological Society of Australasia (UGSA) were invited to complete the draft questionnaire and provide comment to ensure relevance and usability. Feedback provided was incorporated into the final design.

The survey contained both multiple choice and text answer questions, divided into four sections: clinician demographics, PM training, current PM practices and future training needs. HCPs were asked to report their geographical location in relation to the Modified Monash Model (MMM).24 MMM categories range from MM1 (major cities) to MM7 (very remote communities) and are based on population size and remoteness of each area.

The survey was distributed using the Qualtrics XM (Provo, UT) platform, between 26 June and 31 August 2022 via a QR code and web link. Participant consent was required via a checkbox at the commencement of the questionnaire. To optimise responses, associations willing to send reminder emails were asked to do so 14 days after initial distribution. Participant burden was minimised with a time-efficient survey, containing branching questions and an option to save and return. Forced responses avoided missing data.

Recruitment targeted HCPs providing PM in a range of Australian healthcare settings. Target respondents were identified as medical specialists (UGs, obstetrician-gynaecologists, gynaecologists, general practitioner-obstetricians, urologists), general practitioners (GPs), physiotherapists, and nurses.

Pelvic health physiotherapists were targeted via the Continence Foundation of Australia, Australian Physiotherapy Association (APA) Women’s, Men’s and Pelvic Health Group Facebook page, relevant public health facilities, hospital women’s/pelvic health clinical networks, unit managers of known public health pessary clinics, continence clinics and remote continence services, and known physiotherapy pessary/women’s health education and training networks. Pessary suppliers also distributed the survey to HCPs or professional organisations purchasing pessaries. Recruitment amongst professional contacts also occurred via email, flyers, and social media advertising. As there were no existing data on pessary services or providers, an ideal sample size could not be estimated. Snowball and purposive sampling methods prevented calculating a response rate because the number of individuals who viewed the recruitment materials but did not complete the survey was unknown.

Data were exported to Excel in csv format for cleaning before importation into Jamovi 2.325 for statistical analysis. Missing data were accounted for and results from partially completed surveys were included in statistical analyses. Calculations relating to percentages were adjusted to reflect the individual question response rate.

Responses were analysed using descriptive statistics and key variables were reported using frequencies (numbers and percentages), including physiotherapist professional profile, geographical location of physiotherapy services, clinical settings, aspects of PM, and training. Descriptive statistics were also employed to analyse years in profession, years fitting pessaries, number of pessaries fitted per month, geographical areas, clinical settings, pessary types used, age groups of patients managed with pessaries, completed training, mentoring and desire for future training. Respondents who agreed that patients travelled long distances to access pessary services were analysed per geographical area. Finally, a density map was created to demonstrate the distribution of physiotherapists providing PM across Australia.

Results

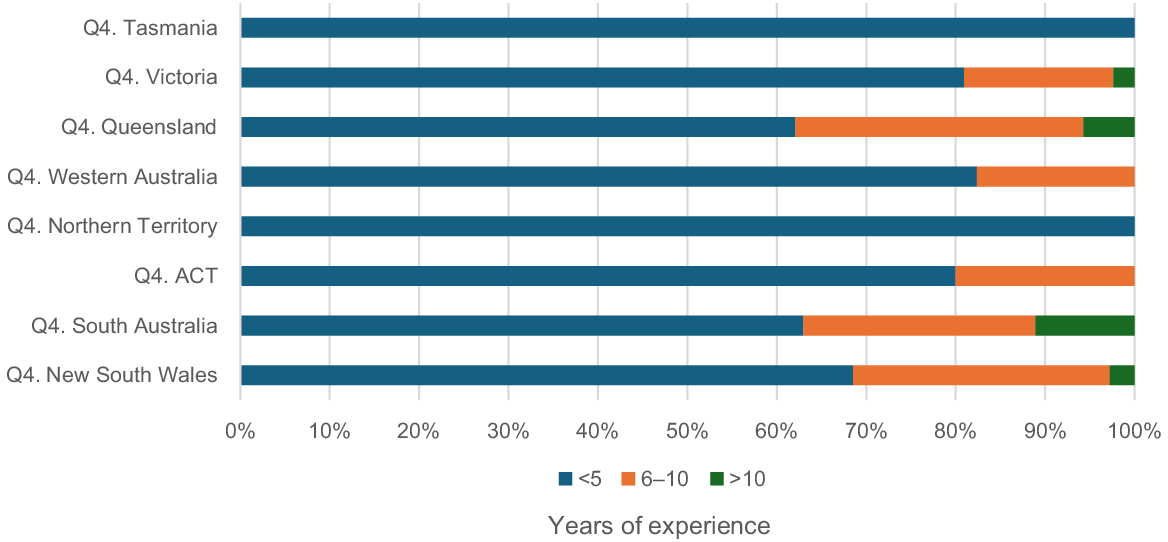

Of the 536 respondents, 324 (60%) were physiotherapists, who were distributed widely across Australia (Fig. 1). Results in this paper pertain to those 324 physiotherapist respondents.

Geographical distribution of physiotherapy respondents providing pessary management across Australia.

Geographical distribution

Physiotherapists were located widely around the continent but most densely around the eastern and southern coasts (Fig. 1).

Table 1 details the distribution of physiotherapists across the regions in Australia, according to their Modified Monash Model (MMM) category. Sixty-six per cent worked in metropolitan areas, 19% in regional areas, 25% in rural towns, and 1% in remote communities. None worked in very remote communities.

| Distribution according to MMM location | n (%) A | |

|---|---|---|

| MM1 Metropolitan | 210 (66) | |

| MM2 Regional | 62 (19) | |

| MM3 Rural (large) | 40 (13) | |

| MM4 Rural (medium) | 23 (7) | |

| MM5 Rural (small) | 15 (5) | |

| MM6 Remote | 4 (1) | |

| MM7 Very remote | 0 (0) | |

| Total | 354 (111) |

Key: Modified Monash Model (MMM) location, Metropolitan (Major Australian Cities accounting for 70% of Australia’s Population) (MM1); Regional Centres, >50,000 residents (MM2); Large Rural Towns, 15,000–50,000 residents (MM3); Medium Rural Towns, 5000–15,000 residents (MM4); Small Rural Towns, All remaining Distribution regional areas – 1000–5000 residents (MM5); Remote Communities, Mainland communities <1000 residents, or islands <5 km offshore (MM6); Very remote areas, all other communities or islands >5 km offshore (MM7).

Physiotherapists delivered pessary care across all Australian states and territories. Details of the distribution per state and territory are provided in Table 2.

| State/Territory | n (%) A | |

|---|---|---|

| New South Wales | 108 (34) | |

| Queensland | 87 (27) | |

| Victoria | 42 (13) | |

| Western Australia | 34 (11) | |

| South Australia | 27 (8) | |

| Australian Capital Territory | 10 (3) | |

| Tasmania | 7 (2) | |

| Northern Territory | 6 (2) | |

| Total | 321 (99) |

Over half of the 321 respondents to the question (n = 179, 56%) indicated that women travelled a long distance to see them for PM.

Clinical setting

Table 3 describes the clinical settings (public or private practice) in which physiotherapy respondents (n = 303) worked. Multiple responses were allowed to the survey questions about clinical settings, allowing for the fact that physiotherapists could work in more than one setting. Thirty physiotherapists (1%) reported working across both settings. Fifty-nine responses were recorded from physiotherapists working in the public system, and 291 from those in private practice. Another four worked in private hospital settings.

| Clinical settings | n (%) A | |

|---|---|---|

| Public pessary services | 59 (17) | |

| Hospital outpatient department | 47 (80) | |

| Public Pessary clinic | 4 (7) | |

| Community clinic | 5 (8) | |

| Other: Rural/outreach | 3 (5) | |

| Private practice | 291 (82) | |

| 1 pessary provider in physiotherapy practice | 89 (31) | |

| 1 pessary provider in MDT | 51 (18) | |

| >1 pessary provider in physiotherapy practice | 82 (28) | |

| >1 pessary provider in multidisciplinary team | 71 (24) | |

| Private hospital | 4 (1) | |

| Total | 354 (109) |

Of the 291 physiotherapists in a private practice setting, 153 (53%) provided pessary care with other pessary providers, while 89 (31%) reported working in a single-discipline physiotherapy practice with only one pessary provider. A further 51 (18%) were the only pessary provider in a multidisciplinary practice.

Table 4 provides further details of the shared-care arrangements of the physiotherapy respondents with doctors and nurses. Of the 205 private practitioner respondents in private practice, 57 (28%) stated that they did not have a shared-care arrangement with other health care providers. Others reported shared-care arrangements with medical and nursing pessary professionals.

| Shared-care arrangements with other HCPs | n (%) private practitioner respondents A | |

|---|---|---|

| No shared-care arrangements | 57 (28) | |

| UG | 83 (41) | |

| Gynaecologist | 144 (70) | |

| General practitioner | 165 (81) | |

| Nurse | 14 (7) |

Experience and training

Physiotherapy pessary providers had been practising in their profession for a mean of 16.8 [range: 2–45] years. The majority (n = 216, 67%) had more than 10 years’ experience as a physiotherapist, while 26 (8%) had been practising for less than 5 years.

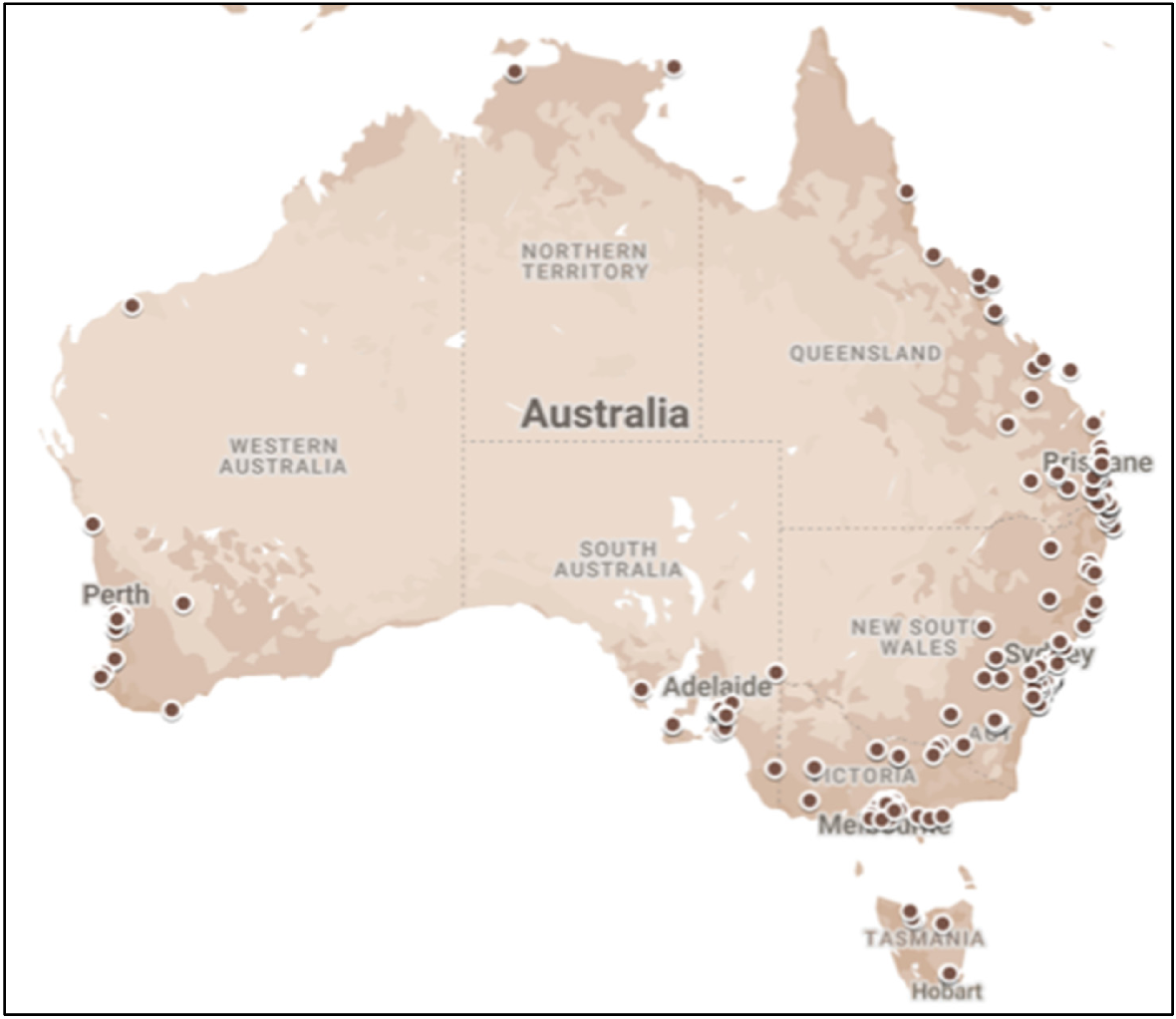

Physiotherapists had a mean of 4.2 [range: 0.5–15] years’ experience in managing pessaries. While 12 (4%) had >10 years’ experience in PM and 81 (25%) had 6–10 years’ experience, the majority (n = 229, 71%) had ≤5 years’ experience. Seventy-three (23%) reported less than 1 year’s experience in PM. Fig. 2 shows the distribution of physiotherapists and their experience in PM per state/territory.

Physiotherapists reported completing various types of training methods in PM. With more than one response allowed, of the 300 respondents to this questions, 244 (81%) reported completing 1–2 day professional development courses, 161 (53%) reported receiving training via mentoring or on-the-job training, and 91 (30%) had a specific university-based qualification in PM. Forty respondents (13%) had completed both professional development training and had a postgraduate qualification in PM. Seven (2%) stated that they had received only on-the-job training or mentoring.

Of all 324 respondents, there were 26 (8%) with <5 years’ experience as a physiotherapist. Of these, 20 (6%) reported their highest level of PM training was via a professional development course, 4 (1%) had no mentoring or support, 8 (3%) reported being the sole pessary provider in a private practice, and 12 (4%) reported having no workplace competency standard.

Physiotherapists were asked whether their workplace required demonstration of their competence in PM, with 174 (57.4%) responding ‘No’ and 129 (42.6%) responding ‘Yes’. By contrast, 100% of four physiotherapists working in public health service pessary clinics were required to demonstrate their competence.

Mentoring

Approximately one-third (n = 105, 35%) of physiotherapy respondents stated that they received no mentoring or support in PM. 119 (40%) respondents reported providing mentoring or support to others. Amongst the small group of 12 physiotherapists with the most PM experience (>10 years), 10 (83%) were providing mentoring or support to others. Of the 154 physiotherapy respondents with 3 or less years’ pessary management experience, 28 (18%) provided mentoring or support to others. Nine (12%) of the 73 physiotherapists with the least experience in PM (1 year or less) reported mentoring others.

Most physiotherapists (n = 244, 81%) stated that they wanted further training, particularly those in rural and remote areas. Over two thirds (n = 219, 68%) wanted education about complex cases, others about adverse events (n = 131, 40%) and risk mitigation (n = 126, 39%).

Pessary practice

Physiotherapists reported using 14 different types of pessaries (in descending order of frequency): ring, ring with support, cube, Gellhorn, donut, dish, shaatz, C-POP, ring with knob, cup, marland, hodge, oval, inflatoball. The first choice of pessary was a ring for 262 (84%) physiotherapists and for 22 (7%) the first choice was a cube pessary. Cubes were the most common second choice for 164 (55%) of physiotherapy respondents, while 3 (1%) and 32 (11%) respectively chose a Gellhorn as their first or second choice. Twelve (4%) physiotherapists only fitted ring pessaries. Fifty-five (18%) reported fitting combinations of two or more pessaries.

Physiotherapists reported fitting a median of three pessaries per month. While a small number (n = 28, 9%) fitted 10–20 per month, there were 40 (13%) who fitted less than one pessary per month. Three hundred and three respondents provided further information about their PM: 298 (98%) provided pessary sizing and fitting, 288 (95%) provided follow-up, and 301 (99%) taught pessary self-management.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first Australian national survey, and most comprehensive internationally, reporting PM practices by physiotherapists. This study has identified physiotherapists as providers of PM for women in all Australian states and territories and in many metropolitan, rural and remote regions across the country. Few physiotherapists are working in the public health system in pessary clinics, whilst the majority are working in private physiotherapy practices, often as sole providers of pessary care, with varying degrees of training and support. Physiotherapists are using a range of pessary types and nearly all are teaching women how to self-manage their pessary.

Physiotherapists as pessary providers

There have been few studies internationally describing the role of physiotherapists in managing pessaries for women with POP and none with comparably detailed data. Our finding of 324 physiotherapists managing pessaries in Australia is remarkable when compared with previous reports. A French multidisciplinary survey of pessary practice reported 208 physiotherapists (20% of all respondents) provided pessary care7 while a recent UK survey of pessary practice reported only 22 physiotherapists (2% of 917 survey respondents).6 In a survey of organisations delivering pessary care in the UK, 10 physiotherapists were reported to be part of multidisciplinary teams across 10 organisations.2 Our data may represent a very successful recruitment campaign for this survey among our pelvic health physiotherapy colleagues. Accordingly, we have been able to demonstrate large numbers of physiotherapists providing pessary care compared with international reports, possibly corresponding with the availability of training opportunities in Australia in the last decade.

The provision of PM by physiotherapists to women in their local and regional areas may also relieve pressure on gynaecology and UG services in the public sector, where, anecdotally, there have been some recent initiatives to develop physiotherapy-led pessary clinics. These have been inspired by the demonstrated efficiencies of Advanced Practice physiotherapy practitioners providing first contact services in gynaecology/UG services.11,12 The outcomes of these initiatives are yet to be reported but they may provide a template for the expansion of physiotherapy scope of practice to enable more women to receive PM in a timely way.

The finding that physiotherapists are providing pessary care across all states and regions of Australia is novel information indicating that physiotherapists can provide opportunities for women to access PM in their primary health care setting. This may be more convenient and save travel to potentially distant tertiary care centres, a model suggested to increase accessibility of health care services.26 The distribution map suggests considerable areas of service inequality, and although we have indicated the location of all physiotherapists according to their MMM classification, we are unable to say from our data whether these new pessary services were able to rectify any inequality in access to pessary services for women with prolapse. We were able to report that 56% physiotherapists stated that women had to travel ‘a long distance’ to see them for PM. Future research is warranted to clarify women’s equitable access to pessary services.

Our data indicated that around a quarter of privately practising physiotherapists did not have shared-care arrangements with other health care providers. There are several possible explanations for this finding. Firstly, we did not formally test the survey questions for their construct validity so that respondents may have misinterpreted the question. Secondly, co-management requires a local medical practitioner who has an interest in women’s health and is able to provide the necessary medical care. Thirdly, respondents may not have been aware of the need to have medical or specialised nursing support for aspects of pessary care that are not within the scope of physiotherapy practice, such as routine speculum examination and the diagnosis and management of complications such as bleeding and vaginal infections. This last possibility would suggest the need for national professional standards in pessary training to protect both the public and practitioners from harm. We also highlight the need for the woman’s GP to be upskilled in the management of pessaries to provide effective co-management, particularly for women with prolapse living in rural and remote Australia, where access to medical practitioners is limited.

Experience and training

There have been no previous reports profiling the experience and training of physiotherapists managing pessaries for comparison with our study. Our data show that Australian physiotherapists have between 2 and 45 years’ experience since graduation. By contrast, the longest any had been managing pessaries was 15 years and nearly a quarter had less than 1 year’s experience. The finding that some physiotherapists were inexperienced as pelvic health practitioners and were already managing pessaries deserves further scrutiny and consideration of minimum training standards in the interests of patient safety and access to best practice care.18

There was also a range in the number of pessaries fitted per month, in keeping with the only other survey to report comparative physiotherapy data.6 Our survey found that some physiotherapists were fitting less than one pessary per month, while some in the UK were fitting less than one pessary per year, further highlighting the need to consider minimum standards to develop and maintain competence.

Our findings reflect differences between the Australian and UK healthcare systems. Locally, 291 (90%) of physiotherapists currently providing PM worked in private practices, whereas a recent UK survey of pessary practice found only 10, out of the 22 physiotherapists identified, worked in private practice, with the others employed in the public health system.6 This suggests that assumptions about education and training suitable in one jurisdiction, e.g. the UK, may not be appropriate for Australia. In the UK, for example, most physiotherapists’ scope of practice and competence will be governed by their institution. In Australia, physiotherapy private practice, including pessary management, is only subject to the professional code of conduct and registration board requirements.

To our knowledge, the first documented recommendations for pessary training for health care professions were published in the UK in 2021,20 followed by an Australian E-Delphi study in 2022 with specific training recommendations for Australian physiotherapists.27 This latter study identified a number of differences in scope of practice for Australian physiotherapists and made recommendations for competence standards to address variability in clinical practice and training specific to the Australian healthcare setting. However, at the time of writing, there were no national pessary-specific training recommendations for physiotherapists to address variations in service delivery.

Various methods of teaching PM have been proposed6 but there are currently no data to demonstrate which is the most effective. In a national survey of nursing practices in the United States, mentoring was reported by 65% of 323 respondents as the main form of learning about PM.4 We have reported that Australian physiotherapists both provide and receive mentoring in PM to support their own learning and that of others. However, the finding that inexperienced physiotherapists are mentoring others raises the question of the qualifications deemed necessary for mentors to provide evidence-based and best-practice training in PM.

Shadowing another clinician was a popular form of training used by 83% of clinicians in the UK6 but this method is only feasible for clinicians in public hospital settings. In Australia, opportunities for physiotherapists to work in public pessary clinics or shadow experts are limited, as most physiotherapists provide pessary care in private practices. Different approaches to training may therefore be needed to meet physiotherapists’ desire for more training and to equip them with the knowledge and skills necessary to competently manage pessaries in clinical practice.

We reported on various training methods in Australia (1–2 day courses, mentoring/on-the-job training, university-based training) which may have had differences in the rigour of the training and assessment processes undergone by physiotherapists. Recommended training standards have been published,27 but it is not clear to what extent they have been adopted by training providers.

Respondents to the survey indicated that more than half of workplaces did not require evidence of practitioner competence in pessary management. To our knowledge, current registration and insurance requirements do not mandate that physiotherapists have participated in a specific type or standard of training, or that workplaces demand evidence of competence. However, the Ahpra Physiotherapy Code of Conduct [2022]28 requires physiotherapists to be competent when moving into a new area of practice. Failure to demonstrate competence may have implications for potential misconduct claims or litigation.

Competence in pessary management encompasses the knowledge and skills to identify and manage the associated risks and complications, including the long-term maintenance of women with a pessary.20,27 Physiotherapists who have undergone training which encompasses the competencies recommended in a recent E-Delphi study27 will be well-equipped to do this, in collaboration with the woman’s medical doctor. Women who are unable to self-manage a pessary will need to be managed by a medical/nursing team.

Pessary self-management

We reported that physiotherapists in the current study almost all taught pessary self-management, which differs from other studies where only 65% of the health care providers, not specifically physiotherapists, taught women how to remove and insert their pessary.7 A recent randomised controlled trial demonstrated the benefits of pessary self-management with reduced risk of complications, cost benefits and improved self-efficacy, with equivalent quality of life outcomes compared with clinic-based care.29 The Australian healthcare system appears well placed to have physiotherapists deliver this evidence-based pessary service, provided that training programmes meet competency standards.

Pessary practices

Australian physiotherapists reported using a wider range of pessaries compared with physiotherapists in the UK,6 an understandable finding when more Australian physiotherapists were providing PM. Ring pessaries were also the most commonly used by physiotherapists in several other studies6,7 and, also consistent with our data, cube pessaries were the next most frequently used pessary.6,7 The frequent use of cube pessaries possibly reflects the younger age of women, less than 60 years of age, receiving PM from physiotherapists15 and their ability to remove and re-insert a cube pessary themselves daily, as required by current guidelines.20 Similarly, some physiotherapists reported fitting women with Gellhorn pessaries, in line with recent research.30 As suggested in the case of cube pessaries, the younger women will likely have had greater flexibility and dexterity, potentially enabling them to successfully self-manage a Gellhorn.

Our findings suggest several opportunities. Firstly, there is an opportunity for enhanced interdisciplinary collaboration with the woman’s GP and her gynaecologist/UG to meet the needs of women wishing to manage their prolapse with a pessary co-managed by a physiotherapist. One cogent reason for co-management is that clinical practice guidelines require the exclusion of pathology and management of complications by a medical practitioner,20 as these are not within the scope of physiotherapy. Secondly, the trend in PM delivery from publicly funded institutions to private physiotherapy practice in primary care settings that we have identified demands a review of the funding structure for PM. Currently women bear the cost of PM when exercising their right to choose local treatment from a physiotherapist, at the same time reducing the financial impact on the public purse.

Thirdly, we suggest an opportunity to develop joint competencies and training standards with all professionals managing pessaries, in order to ensure that all women receive best-practice, evidence-based pessary care. Further research to understand optimal pessary care arrangements, including professional and financial barriers, is warranted. However, we affirm the need for specific Australian physiotherapy competencies as clarity is needed to support physiotherapists to safely navigate the limits of their current scope of practice.

Our results also highlight a number of challenges which potentially impact the delivery of best-practice PM. Challenges include variability in physiotherapists’ experience in women’s health practice, lack of a requirement for standardised, competency-based training in PM, unregulated mentoring practices, the perceived need for more training, and variable governance of pessary provision. It has been argued that PM demands advanced knowledge and skills for the practitioner to deliver a high standard of safe care18 and that standardised, quality, competence-assessed training should be available.6,8,18,31 In line with these recommendations, our data suggest that Australian pessary training standards are urgently needed for physiotherapists, ‘to protect themselves as practitioners, to protect the availability of pessaries as a treatment option, and, most importantly, to protect patients’.18

Strengths and limitations

We believe that this is the first international study to describe physiotherapy practices in PM in detail. A major strength of our study was the high number of responses, identifying the large number of physiotherapists involved in pessary care in Australia. This response rate was likely due to our extensive professional connections as physiotherapy researchers and the willingness of pelvic health physiotherapists in Australia to contribute to research. However, we acknowledge a limitation in our study design, which prevents us from estimating the total number of physiotherapists delivering pessary care. As a result, we could not determine how many did not receive or did not respond to our survey.

A possible limitation in the interpretation of our survey results arises from the timing of the survey soon after the Covid pandemic. It is unknown what effect the pandemic had within public and private settings, but it is possible that services may not have been fully functional again. However, we have reported large numbers of physiotherapists working in the private sector and the relatively small number working in the public sector (4 in pessary clinics, 47 in public hospital outpatient departments15) could also have been related to the historical staffing of pessary clinics by doctors and nurses.

Conclusions

Physiotherapists who manage pessaries are now widely distributed across Australia, with most pessary services provided in private practice settings rather than public health facilities. This shift presents challenges for the governance and regulation of pessary practice standards. Physiotherapists’ experience as pelvic health practitioners and as pessary providers is varied, with many expressing a wish for more training. Physiotherapists are providing PM with a range of pessaries and teaching women to self-manage.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest

PBN and RD declare receipt of payment from Uni SA for teaching a course on pessary management. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest relating to the preparation and publication of this paper.

References

1 Gorti M, Hudelist G, Simons A. Evaluation of vaginal pessary management: a UK-based survey. J Obstet Gynaecol 2009; 29(2): 129-31.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

2 Dwyer L, Stewart E, Rajai A. A service evaluation to determine where and who delivers pessary care in the UK. Int Urogynecol J 2021; 32: 1001-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 Hanson L-AM, Schulz JA, Flood CG, Cooley B, Tam F. Vaginal pessaries in managing women with pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence: patient characteristics and factors contributing to success. Int Urogynecol J 2006; 17: 155-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

4 O’Dell K, Atnip S, Hooper G, Leung K. Pessary practices of nurse-providers in the United States. Urogynecology 2016; 22(4): 261-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

5 Bugge C, Hagen S, Thakar R. Vaginal pessaries for pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence: a multiprofessional survey of practice. Int Urogynecol J 2013; 24: 1017-24.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

6 Brown CA, Pradhan A, Pandeva I. Current trends in pessary management of vaginal prolapse: a multidisciplinary survey of UK practice. Int Urogynecol J 2021; 32: 1015-22.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

7 Pizzoferrato A-C, Nyangoh-Timoh K, Martin-Lasnel M, Fauvet R, de Tayrac R, Villot A. Vaginal pessary for pelvic organ prolapse: a French multidisciplinary survey. J Womens Health 2022; 31(6): 870-7.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

8 Newman S, Rantell A. A specialist service evaluation: a cross-sectional survey approach. B J Nurs 2023; 32(12): 570-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

9 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Population aged over 85 to double in the next 25 years. Canberra: ABS; 2018. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/population-aged-over-85-double-next-25-years [cited 7 December 2024]

10 National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse in women: management; 2019. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng123 [Last updated 24 June 2019, cited 5 December 2024]

11 Goode K, Beaumont T, Kumar S. Timing is everything: an audit of process and outcomes from a pilot advanced scope physiotherapy model of care for women with pelvic floor conditions. Clinical Audit 2019; 2019: 1-10.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

12 Nucifora J, Howard Z, Weir KA. Do patients discharged from the physiotherapy-led pelvic health clinic re-present to the urogynaecology service? Int Urogynecol J 2022; 33: 689-95.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

13 Beaumont T, Tian E, Kumar S. “It’s messing with my physical health. It’s messing with my sex life”: women’s perspectives about, and impact of, pelvic health issues whilst awaiting specialist care. Int Urogynecol J 2022; 33(9): 2463-70.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

14 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Rural and remote health. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2024. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/rural-remote-australians/rural-and-remote-health [cited 7 December 2024]

15 McEvoy K, Griffin R, Harris M, Moger H, Wright O, Nurkic I, Thompson J, Das R, Neumann P. Pessary management practices for pelvic organ prolapse among Australian health care practitioners: a cross-sectional study. Int Urogynecol J 2023; 34(10): 2519-27.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

16 Brennen R, Sherburn M, Rosamilia A. Development, implementation and evaluation of an advanced practice in continence and women’s health physiotherapy model of care. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2019; 59(3): 450-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

17 Abdulaziz M, Stothers L, Lazare D, Macnab A. An integrative review and severity classification of complications related to pessary use in the treatment of female pelvic organ prolapse. Can Urol Assoc J 2015; 9(5-6): E400-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

18 Dwyer L, Kearney R, Lavender T. A review of pessary for prolapse practitioner training. B J Nurs 2019; 28(9): S18-24.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

19 O’Dell K, Wooldridge LS, Atnip S. Managing a pessary business. Urol Nurs 2012; 32(3): 138-45.

| Google Scholar |

20 UK Clinical Guideline Group. UK Clinical Guideline on best practice in the use of vaginal pessaries for pelvic organ prolapse; 2021. Available at https://www.ukcs.uk.net/UK-Pessary-Guideline-2021 [cited 5 December 2024]

21 Neumann P, Scammell A, Burnett A, Thompson J, Briffa N. Training of Australian health care providers in pessary management for women with pelvic organ prolapse: outcomes of a novel program. Aust N Z Cont J 2015; 21(1): 6-12.

| Google Scholar |

22 Vardon D, Martin-Lasnel M, Agostini A, Fauvet R, Pizzoferrato A-C. Vaginal pessary for pelvic organ prolapse: a survey among french gynecological surgeons. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 2021; 50(4): 101833.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

23 Open Science Framework. Guidelines for the use of support pessaries in the management of pelvic organ prolapse. OSFHOME; 2012. Available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/7MES5

24 Australian Government - Department of Health and Aged Care. Modified Monash Model; 2021. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/rural-health-workforce/classifications/mmm [cited 5 December 2024]

25 The jamovi project. jamovi (Version 2.3); 2025. [Computer Software]. Available at https://www.jamovi.org [cited 21 May 2025]

26 Hall CEJ, Kay V. Shifting care closer to home: limitations and challenges of implementing a community vaginal pessary service. J Obstet Gynaecol 2010; 30(7): 754.

| Google Scholar |

27 Neumann PB, Radi N, Gerdis TL, Tonkin C, Wright C, Chalmers KJ, Nurkic I. Development of a multinational, multidisciplinary competency framework for physiotherapy training in pessary management: an E-Delphi study. Int Urogynecol J 2022; 33(2): 253-65.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

28 Ahpra. Code of Conduct; 2022. Available at https://www.physiotherapyboard.gov.au/Codes-Guidelines/Code-of-conduct.aspx [cited 27 March 2025]

29 Hagen S, Kearney R, Goodman K, Best C, Elders A, Melone L, Dwyer L, Dembinsky M, Graham M, Agur W, Breeman S, Culverhouse J, Forrest A, Forrest M, Guerrero K, Hemming C, Khunda A, Manoukian S, Mason H, McClurg D, Norrie J, Thakar R, Bugge C. Clinical effectiveness of vaginal pessary self-management vs clinic-based care for pelvic organ prolapse (TOPSY): a randomised controlled superiority trial. eClinicalMedicine 2023; 66: 102326.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

30 Mao M, Ai F, Kang J, Zhang Y, Liang S, Zhou Y, Zhu L. Successful long-term use of Gellhorn pessary and the effect on symptoms and quality of life in women with symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse. Menopause 2019; 26(2): 145-51.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

31 Lough K, Hagen S, McClurg D, Pollock A. Shared research priorities for pessary use in women with prolapse: results from a James Lind alliance priority setting partnership. BMJ Open 2018; 8(4): e021276.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |