Use of targeted SMS messaging to encourage COVID-19 oral antiviral uptake in South West Victoria

Naomi Clarke A * , Jessica O’Keeffe A B , Arvind Yerramilli A B , Caroline Bartolo A B , Nomvuyo Mothobi A B , Michael Muleme A , Bridgette McNamara A , Daniel O’Brien A B , Eugene Athan A B C and Mohammad Akhtar Hussain AA

B

C

Abstract

Objectives:During winter 2022, as part of a multifaceted approach to optimise oral antiviral uptake in the Barwon South West region in Victoria, Australia, the Barwon South West Public Health Unit (BSWPHU) implemented an innovative, targeted SMS messaging program that encouraged people with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) to be assessed for antiviral treatment. In this study, we investigated patterns of antiviral uptake, identified barriers and facilitators to accessing antivirals, and examined the potential impact of targeted SMS messaging on oral antiviral uptake. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study of notified COVID-19 cases aged 50 years and older, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 30-49 years, in the BSWPHU catchment area over a 6-week period commencing 21 July 2022. We analysed survey data using descriptive statistics and generalised linear models. Results: Of the 3829 survey respondents, 36.7% (95% confidence interval (CI) 35.2, 38.2) reported being prescribed oral antivirals, with 75.4% (95% CI 72.8, 77.9) of these aged ≥70. Antiviral prescriptions increased significantly over the 6-week survey period. Most prescriptions (87.5%; 95% CI 85.7, 89.2) were provided by the respondents’ usual general practitioners (GPs). Barriers to receiving antivirals included respondents being unable to get a medical appointment in time (3.7%; 95% CI 3.1, 4.2), testing too late in their illness (2.3%; 95% CI 1.8, 2.8) and being unable to access medications in time after receiving a prescription (0.2%; 95% CI 0.1, 0.6). Facilitators to receiving antivirals included respondents first hearing about antivirals from a trusted source such as a family member, friend or usual doctor. Nearly one in eight people who were prescribed antivirals reported first hearing about them from the SMS message sent by BSWPHU. Conclusions: Oral antiviral treatment uptake in south-west Victoria in July−August 2022 was high among survey respondents and increased over time. GPs were the key prescribers in the community. Targeted SMS messaging to COVID-19 cases is a simple, low-cost intervention that potentially increases antiviral uptake.Introduction

Developing biomedical interventions to reduce transmission and improve patient outcomes for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been a key priority since the disease’s emergence in 2020. Following the publication of efficacy and safety data for two oral antiviral agents, molnupiravir (Lagevrio®; Merck Sharp & Dohme Australia) and a combination of nirmatrelvir and ritonavir (Paxlovid®; Pfizer Australia)1,2, Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration granted provisional approval for both agents on 18 January 2022.3 Lagevrio and Paxlovid were then listed on Australia’s subsidised medication program, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), on 1 March and 1 May 2022, respectively.4,5 Eligibility criteria gradually expanded over time (Box 1).

Box 1: PBS eligibility for COVID-19 oral antivirals6

From 11 July 2022, individuals with mild to moderate COVID-19 were eligible for molnupiravir or nirmatrelvir and ritonavir via the PBS if they were either:

a) aged ≥70

b) aged 50-69 with at least two risk factors for severe disease

c) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 30-49 with at least two risk factors for severe disease

d) moderately to severely immunocompromised and aged ≥18.

Treatment was to be initiated within 5 days of symptom onset, or if asymptomatic, as soon as possible following diagnosis. For asymptomatic people, only those aged ≥70 were eligible for oral antivirals.

Australia experienced a significant surge in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections between June and August 2022, driven by the Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 sublineages.7 Given the high case numbers and expanded eligibility criteria, many people were eligible for oral antivirals during this time. The Barwon South West Public Health Unit (BSWPHU) in collaboration with the Western Victoria Primary Health Network (WVPHN), implemented a multipronged approach throughout 2022 to improve awareness and uptake of antivirals, which included the following key components:

Facilitating clinician education across primary and tertiary health sectors

Ensuring appropriate referral pathways were available, which included collaborating with government-funded GP Respiratory Clinics (GPRCs), working with COVID Positive Pathways teams (who provided targeted care and support for individuals with COVID-19 in Victoria)8, and providing a specialist referral service

Working closely with high-risk settings such as residential care facilities to ensure appropriate antiviral prescription

Developing a public communications campaign, including messaging to priority groups.

As well as broad community messaging, in May 2022 we implemented an innovative, targeted messaging program. This involved sending an SMS message to newly notified COVID-19 cases in the Barwon South West (BSW) region who were potentially eligible for oral antivirals, prompting them to be assessed for treatment.

SMS messaging is a simple, low-cost communication method that is increasingly being used to deliver health interventions and promote healthy behaviours.9 This reflects the burgeoning field of mobile health (mHealth), defined by the World Health Organization as “medical and public health practice supported by mobile devices”.10 Meta-analyses have shown that SMS messaging has positive effects on health behaviours such as medical appointment attendance, medication adherence and the adoption of healthy lifestyle choices9,11,12. In recent years, SMS messaging has also successfully been used to increase uptake of COVID-19 vaccinations.13,14 We did not identify any previous analyses of targeted SMS messaging about COVID-19 antiviral medications.

Barriers to receiving oral antivirals that have been reported in other countries include a lack of public awareness, insufficient clinician education, limited pathways for clinical evaluation before treatment, and logistical challenges in medication dispensing.15 However, there is limited understanding of the Australian community’s awareness, perception and uptake of oral antivirals.

We report the results of a survey conducted to inform local efforts to improve antiviral uptake. The specific objectives of the survey were to:

a) Investigate patterns of oral antiviral prescription in south-west Victoria following the expansion of eligibility criteria on 11 July 2022

b) Understand potential barriers and facilitators to accessing oral antivirals

c) Examine the potential impact of targeted SMS messaging on oral antiviral uptake.

Methods

Setting

The BSWPHU catchment area (population approximately 464 000) encompasses 10 local government areas (LGAs) in south-west Victoria, Australia, and includes Victoria’s largest regional city, Geelong (Supplementary Figure S1, available from: doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24155514). The region experienced a significant surge in COVID-19 infections in July−August 2022, peaking at more than 1000 cases a day in mid-July (Supplementary Figure S2, available from: doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24155514).

Targeted SMS messaging

From 25 May 2022, BSWPHU sent an SMS message to COVID-19 cases who were potentially eligible for oral antivirals based on their age and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status. The messaging was updated from 11 July 2022 to reflect the PBS eligibility criteria (Supplementary Text S1, available from: doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24155514).

The SMS message advised COVID-19 cases who were aged ≥70 of their eligibility for antivirals. Those aged 50–69, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 30–49, were informed of their potential eligibility and referred to eligibility criteria published online.16 All cases were advised to contact their general practitioner (GP) or local GPRC.

Messages were sent daily, using the online platform SMS Broadcast, to all confirmed and probable COVID-19 cases in the above groups who had been notified to the Victorian Department of Health in the previous 24 hours and: a) had a postcode in the BSWPHU catchment; b) had an Australian mobile phone number; and c) were not a recent confirmed case, as defined in the Quarantine Isolation and Testing Order in place at the time.17 Cases were identified using the Transmission and Response Epidemiology Victoria (TREVi) database.

Project design and data collection

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of COVID-19 cases in the BSWPHU catchment. All cases who were sent an SMS message between 11 July and 21 August 2022 were sent a link to an anonymous online survey 10 days later. The survey collected basic demographic data (age group and postcode) and information about the respondents’ experiences with oral antivirals, including where prescriptions were accessed, the type of antiviral prescribed and how long it took to access antivirals, or the reasons why they were not prescribed antivirals. The survey also asked where respondents first heard about oral antivirals for COVID-19.

This study received ethics approval from the Research Ethics, Governance and Integrity Unit at Barwon Health (QA/91034/VICBH-2022-338494).

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics (proportions and 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) to examine responses overall and by age group. We compared proportions between age groups (≥70 versus <70) and between those who were and were not prescribed antivirals using two-sample Z tests for proportions. We used generalised linear models to examine the impact of age group, local government area (LGA) and survey week on the odds of being prescribed oral antivirals, and to examine changes over time. All analyses were completed using Stata software version 15.1 (College Station, Texas, US).

Results

Survey respondents

From 7010 survey invitations sent over the survey period (11 July–21 August 2022), we received 3829 responses (54.6% response rate). Most respondents (70.4%) were aged 50–69, 28.2% were aged ≥70, 0.9% were aged 30–49, and 0.6% did not specify their age group. Nearly two-thirds of respondents (60.6%) reported a home postcode within the City of Greater Geelong, 7.1% within Surf Coast Shire and 6.8% within City of Warrnambool. There were less than 5% of respondents with home postcodes within each of the remaining LGAs.

Patterns of antiviral prescription

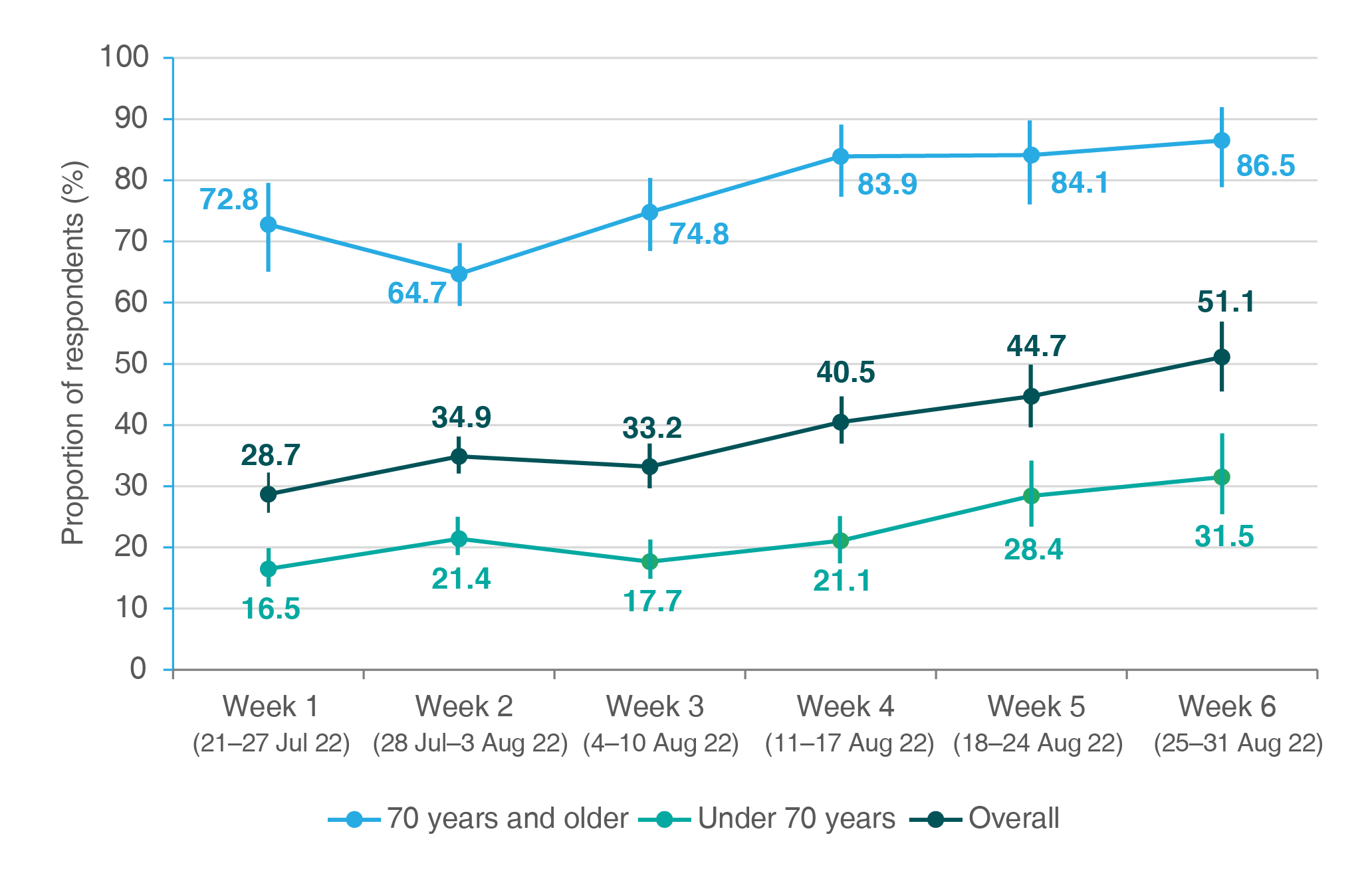

Of the survey responses received between 21 July and 31 August 2022, just over one-third (36.7%; 95% CI 35.2, 38.2) reported being prescribed oral antivirals. Prescription rates were much higher among respondents aged ≥70 (75.4%; 95% CI 72.8, 77.9) than those aged <70 (21.1%; 95% CI 19.6, 22.6). The proportion of respondents that reported being prescribed antivirals increased over the survey period (Figure 1). Details of antiviral prescriptions by age group, LGA and survey week are shown in Supplementary Table S1, available from: doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24155514.

Proportion of survey respondents who were prescribed oral antiviral medications, by survey week and age group (N = 3829)

Note: Vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

As shown in Table 1, the odds of respondents having been prescribed oral antivirals were higher in survey weeks 4, 5 and 6 than in survey week 1. Compared with Greater Geelong, six LGAs had lower odds of antiviral prescription and two LGAs had higher odds; however, most of these results were not statistically significant.

| Covariate | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI | pvalue | |

| Age group | ||||

| 30−49 yearsa | 0.69 | 0.26, 1.82 | 0.454 | |

| 50−69 years | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | |

| ≥70 years | 11.71 | 9.86, 13.91 | <0.001 | |

| Survey week (2022) | ||||

| Week 1 (21–27 July) | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | |

| Week 2 (28 July–3 August) | 1.07 | 0.84, 1.36 | 0.592 | |

| Week 3 (4–10 August) | 1.11 | 0.86, 1.44 | 0.417 | |

| Week 4 (11–17 August) | 1.49 | 1.14, 1.95 | 0.003 | |

| Week 5 (18–24 August) | 1.98 | 1.47, 2.67 | <0.001 | |

| Week 6 (25–31 August) | 2.36 | 1.71, 3.26 | <0.001 | |

| Local government area | ||||

| Colac Otway Shire | 0.66 | 0.45, 0.99 | 0.043 | |

| Corangamite Shire | 0.81 | 0.46, 1.42 | 0.458 | |

| Glenelg Shire | 0.63 | 0.39, 1.00 | 0.051 | |

| City of Greater Geelong | (ref) | (ref) | (ref) | |

| Golden Plains Shire | 0.74 | 0.50, 1.08 | 0.119 | |

| Moyne Shire | 1.18 | 0.72, 1.90 | 0.533 | |

| Borough of Queenscliffe | 1.44 | 0.85, 2.46 | 0.175 | |

| Southern Grampians Shire | 1.02 | 0.67, 1.55 | 0.915 | |

| Surf Coast Shire | 0.80 | 0.58, 1.09 | 0.159 | |

| City of Warrnambool | 0.86 | 0.62, 1.17 | 0.330 | |

| Other (outside Barwon South West) | 0.80 | 0.44, 1.46 | 0.478 | |

| Constant | 0.23 | 0.18, 0.27 | <0.001 |

CI = confidence interval; ref = reference group

a Survey only included Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people for this age group.

Table 2 details which antivirals were prescribed, where prescriptions were accessed and if the five-day antiviral course was completed. GPs provided most prescriptions, specifically usual GP practices and GPRCs. There were no significant changes over time in the prescription source or types of antivirals prescribed (Supplementary Table S2, available from: doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24155514).

| Proportion of respondents, % (95% CI) | ||||

| Overalla (N = 1404) | Aged ≥70 (n = 813) | Aged <70b (n = 575) | ||

| Antiviral agent prescribed | ||||

| Molnupiravir (Lagevrio) | 67.1 (64.6, 69.5) | 66.8 (63.5, 69.9) | 67.8 (63.9, 71.5) | |

| Nirmatrelvir and ritonavir (Paxlovid) | 25.0 (22.8, 27.4) | 23.7 (20.9, 26.8) | 27.0 (23.5, 30.7) | |

| Could not remember | 7.7 (6.4, 9.3) | 9.5 (7.6, 11.7) | 4.9 (3.4, 7.0) | |

| Source of antiviral prescription | ||||

| Usual GP/practice | 87.5 (85.7, 89.2) | 88.7 (86.3, 90.7) | 85.9 (82.8, 88.5) | |

| GP Respiratory Clinic | 4.1 (3.2, 5.3) | 4.3 (3.1, 5.9) | 4.0 (2.7, 5.9) | |

| Other doctor involved in care | 2.3 (1.6, 3.2) | 1.7 (1.0, 2.9) | 3.1 (2.0, 4.9) | |

| Hospital (including emergency department) | 2.6 (1.9, 3.5) | 2.7 (1.8, 4.1) | 2.1 (1.2, 3.6) | |

| COVID Positive Pathways team | 2.7 (2.0, 3.7) | 2.1 (1.3, 3.3) | 3.7 (2.4, 5.5) | |

| Other | 0.8 (0.4, 1.3) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.3) | 1.2 (0.6, 2.5) | |

| Completed antiviral course | ||||

| Yes | 97.2 (96.2, 97.9) | 97.9 (96.7, 98.7) | 96.2 (94.2, 97.5) | |

| No | 2.8 (2.1, 3.8) | 2.1 (1.3, 3.3) | 3.8 (2.5, 5.7) | |

CI = confidence interval; GP = general practitioner

Notes: Denominator is all respondents who reported being prescribed oral antivirals (N = 1404). All findings were not significantly different between age groups

a Some respondents (n = 16) did not specify their age range.

b Includes people aged 50–69 and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 30−49.

Access to medications after prescription

Most respondents accessed medication within 24 hours of receiving a prescription (87.3%; 95% CI 85.4, 88.9), 8.0% (95% CI 6.7, 9.5) accessed it within 24–48 hours, and 2.4% (95% CI 1.7, 3.4) did not access it until more than 48 hours after receiving a prescription. These proportions did not change significantly over the survey period. Three survey respondents (0.2% of those prescribed antivirals) reported that they were not able to access antivirals in time to start treatment.

Treatment completion

Most respondents (97.2%; 95% CI 96.2, 97.9) reported that they completed antiviral treatment (Table 2). Among the 39 individuals who stopped treatment, 22 (1.6% of those prescribed antivirals) reported stopping due to side effects, nine (0.6%) stopped because they felt better or believed treatment was no longer necessary, and two (0.1%) stopped due to the large number of tablets. The remaining six individuals did not provide a reason for stopping treatment. Of those respondents who stopped treatment due to side effects, 11 were prescribed molnupiravir (1.2% of respondents who were prescribed molnupiravir), nine were prescribed nirmatrelvir and ritonavir (2.6% of respondents who were prescribed nirmatrelvir and ritonavir), and two could not recall which antiviral they were prescribed. Reported side-effects included dysgeusia (four respondents), rash (two respondents), nausea, diarrhoea, headaches and dizziness (one respondent each).

Reasons for antivirals not being prescribed

Overall, the most commonly reported reasons for antivirals not being prescribed were the respondent not contacting a doctor due to feeling well, self-assessing as ineligible for antivirals, and being assessed by a doctor as ineligible, as shown in Table 3. Compared with respondents aged ≥70, respondents aged <70 were significantly more likely to report feeling well, self-assessing as ineligible and being assessed as ineligible by their doctor (all p < 0.001). However, respondents aged ≥70 were more likely to report getting tested for COVID-19 too late in their illness to access antivirals than younger respondents (p = 0.013). There was a 10% increase each survey week in the odds of respondents self-assessing as ineligible (OR 1.10; 95% CI 1.04, 1.17), while the odds of other reasons for antivirals not being prescribed did not change over the survey period (See Supplementary Table S3, available from: doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24155514).

| Proportion of respondents (95% CI) | |||||

| Reason | Overalla (N = 3829) | Aged ≥70 (n = 1078) | Aged <70b (n = 2728) | pvaluec | |

| Felt well so did not contact a doctor | 26.1 (24.7, 27.5) | 12.9 (11.0, 15.0) | 31.5 (29.7, 33.2) | <0.001 | |

| Self-assessed as ineligible | 18.2 (17.0, 19.5) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.5) | 25.0 (23.4, 26.2) | <0.001 | |

| Doctor assessed as ineligible | 9.1 (8.2, 10.1) | 1.7 (1.1, 2.6) | 12.1 (10.9, 13.4) | <0.001 | |

| Tested late in illness | 2.3 (1.8, 2.8) | 3.2 (2.3, 4.5) | 1.9 (1.5, 2.4) | 0.013 | |

| Unable to get an appointment | 1.6 (1.3, 2.1) | 1.4 (0.8, 2.3) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.3) | 0.423 | |

| Delays in getting appointment | 2.1 (1.7, 2.6) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.5) | 2.7 (2.1, 3.4) | <0.001 | |

| Contraindications to receiving antivirals | 0.7 (0.5, 1.0) | 0.8 (0.4, 1.6) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.1) | 0.653 | |

| Did not know about antivirals/did not know that antivirals were an option | 0.7 (0.5, 1.0) | 0.4 (0.1, 1.0) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.3) | 0.118 | |

| Personal preference not to have antivirals | 0.4 (0.2, 0.6) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.9) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.8) | 0.473 | |

CI = confidence interval

Notes: Respondents could indicate more than one answer. Denominator is all survey respondents (N = 3829)

a Some respondents (n = 23) did not specify their age range.

b Includes people aged 50-69 and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 30-49.

c p values were calculated using two-sample Z tests comparing the proportions of age groups.

Other reasons that were less commonly reported included not having a GP (two respondents), believing antivirals would be too expensive (two respondents), being concerned about side-effects (one respondent), and being unable to afford a GP appointment (one respondent).

Knowledge of antivirals

Supplementary Table S4 (available from: doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24155514) details the sources from which respondents first heard about oral antivirals for COVID-19. The three most commonly reported sources overall were media (34.7%; 95% CI 33.2, 36.3), the SMS message from BSWPHU (23.8%; 95% CI 22.5, 25.2), and a family member or friend (17.2%; 95% CI 16.0, 18.4). Of those respondents who were prescribed antivirals, 11.8% (95% CI 10.2, 13.6) reported first hearing about oral antivirals from the SMS message from BSWPHU.

Individuals who were prescribed antivirals were significantly more likely to have first heard about antivirals from their GP or other doctor than those who were not prescribed antivirals (p < 0.001), while those who were not prescribed antivirals were significantly more likely to have first heard about antivirals from the SMS message from BSWPHU (p < 0.001). Among respondents aged ≥70, those prescribed antivirals were significantly more likely to have first heard about antivirals from a family member or friend than those not prescribed antivirals (p = 0.002), see Supplementary Table S5 (available from: doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24155514).

Discussion

We observed high rates of oral antiviral uptake among survey respondents, particularly for those aged ≥70. These results are supported by data from the Victorian Department of Health showing that, between 11 July and 10 October 2022, individuals aged ≥70 living in the BSW region were the most likely to be prescribed oral antivirals for COVID-19 in Victoria (personal communication, Victorian Department of Health, 24 October 2022). The increasing rates of antiviral prescription observed over the survey period reflect increased awareness of antivirals among health providers and consumers. We believe the multifaceted approach taken by the BSWPHU, in collaboration with key partners and stakeholders including WVPHN, local GPRCs and high-risk settings, to improve clinician awareness, referral pathways and public knowledge of antivirals, played a key role in the high and increasing prescription rates.

Nearly one-quarter of respondents, including nearly one in eight of those prescribed antivirals, first learned about oral antivirals from the targeted SMS message from BSWPHU. While our study design prevents direct attribution of antiviral uptake to our SMS messaging program, this finding demonstrates that the messaging improved awareness of antivirals among COVID-19 cases. It also may have contributed to broader community awareness through, for example, word of mouth from cases to family and friends, and to increased clinician awareness through patient demand. The findings from our cross-sectional analysis complement those from longitudinal studies and randomised controlled trials demonstrating that targeted SMS messaging increases awareness of health interventions, including those for COVID-19.13,18,19

Sending the SMS messages took less than 10 minutes each day, required minimal training, and cost under A$1200 (A$0.168 per message) over six weeks. This is consistent with previous characterisations of SMS messaging as a simple and cost-effective health intervention.9

Accessible and affordable care pathways are essential to achieve equitable access to COVID-19 treatment.15 GPs were the most common source of antiviral prescriptions, highlighting the important role of primary care in the COVID-19 response. Although referral and supply pathways appeared to be functioning well, some respondents reported a lack of access to medical care and medication as barriers to accessing antivirals; this is consistent with previous findings.15 Lower prescription rates in most LGAs compared with Greater Geelong may reflect challenges in accessing medical appointments and pharmacy services in regional areas.20,21

More than one in eight respondents aged ≥70, and more than one-quarter of respondents aged <70, felt they were too well for antivirals. This highlights opportunities to strengthen community messaging about antiviral treatment eligibility and benefits for high-risk individuals, even if they are not experiencing many symptoms.

Respondents who were prescribed antivirals were more likely than those not prescribed antivirals to have first heard about oral antivirals from a family member or friend, or from their usual GP. This suggests that learning about antivirals from a trusted source may increase the likelihood of accessing them, and that people who are well engaged with a GP may be more likely to seek treatment than those who are not. Healthcare providers in Australia were also encouraged to proactively create COVID-19 action plans with high-risk patients22, which may have contributed to high antiviral uptake.

Limitations

This study has several limitations, the most important being the potential for selection bias. Individuals actively engaged in healthcare may have been more likely to both seek antivirals and participate in this survey than those who are not actively engaged, which may have led to overestimated prescription rates. Self-reporting of antiviral prescriptions can also lead to misclassification (for example, respondents who were prescribed other medications may have mistakenly reported receiving antivirals). Additionally, survey recipients were identified based on the address provided at COVID-19 testing, meaning that a small proportion of survey data may not relate to the BSW region (for example, some people may have been diagnosed in another jurisdiction, or returned to another jurisdiction after being tested).

Finally, because the survey was conducted in English, culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) groups were likely under-represented. Recent Australian data have shown that individuals who were born overseas are more likely to die from COVID-19 than those who were born in Australia.23 Understanding barriers and facilitators to oral antiviral access for people from CALD backgrounds, as well as other priority populations, is crucial to achieve equitable access to treatment.

Conclusion

We observed high and increasing rates of antiviral prescriptions for COVID-19 in the BSW region of Victoria during winter 2022, with most prescriptions provided by GPs. A targeted SMS messaging program was a simple and low-cost intervention that improved awareness of COVID-19 antivirals among clinicians and patients. Larger studies that link to PBS data on medication use are warranted to understand prescription patterns and coverage across Australia, and to further clarify barriers and facilitators to antiviral access. These findings can be used to inform interventions to improve equitable access to treatment across the population.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the team leaders, administrative staff, in-reach testing team and COVID Positive Pathways team at the BSWPHU for their work in sending out the daily SMS messages.

Author contributions

NC led the implementation of the SMS messaging, drafted the survey, conducted the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. MH conceived the SMS messaging and survey. JO, AY, CB, NM, MM, BJM, DO, EA and MH helped develop the SMS messaging and survey and provided feedback on the manuscript. All authors approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

References

3 Therapeutic Goods Administration. TGA provisionally approves two oral COVID-19 treatments, molnupiravir (LAGEVRIO) and nirmatrelvir + ritonavir (PAXLOVID). Canberra, ACT; Australian Government TGA; 2022 Jan 20 [cited 2022 Sep 27]. Available from: www.tga.gov.au/news/media-releases/tga-provisionally-approves-two-oral-covid-19-treatments-molnupiravir-lagevrio-and-nirmatrelvir-ritonavir-paxlovid

4 Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Paxlovid® (nirmatrelvir and ritonavir) PBS listing, Canberra, ACT: Australian Government PBS; 2022 [cited 2022 Sep 27]. Available from: www.pbs.gov.au/info/news/2022/04/paxlovid-nirmatrelvir-and-ritonavir-pbs-listing

5 Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Lagevrio® (molnupiravir) PBS listing. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government PBS; 2022 [cited 2022 Sep 27]. Available from: www.pbs.gov.au/info/news/2022/03/lagevrio-molnupiravir-pbs-listing

6 Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Updated eligibility for oral COVID-19 treatments. Canberra, ACT: Department of Health and Aged Care; 2023 [cited 2023 Sep 18]. Available from: www.health.gov.au/health-alerts/covid-19/treatments/eligibility

8 Victorian Government. COVID Positive Pathways. Victoria: Victorian Government; 2022 [cited 2022 Sep 27]. Available from: www.coronavirus.vic.gov.au/covid-positive-pathways

10 WHO Global Observatory for eHealth. mHealth: new horizons for health through mobile technologies: second global survey on eHealth. Geneva: WHO; 2011 [cited 2023 Sep 4]. Available from: apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44607

16 Victorian Government Department of Health. Antivirals and other medicines. Victoria: Department of Health: 2022 [cited 2022 Sep 27]. Available from: www.coronavirus.vic.gov.au/covid-19-medicines

17 Victorian Government Department of Health. Quarantine Isolation and Testing Order. Victoria: Department of Health; 2022 [cited 2022 Sep 27]. Available from: www.health.vic.gov.au/covid-19/quarantine-isolation-and-testing-order

20 National Rural Health Alliance. Discussion Paper: Access to medicines and pharmacy services in rural and remote Australia [Discussion Paper]. Canberra, ACT: NHRA; 2014 [cited 2023 Sep 4]. Available from: www.ruralhealth.org.au/sites/default/files/documents/nrha-policy-document/policy-development/nrha-medicines-discussion-paper-january-2014.pdf

21 The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. General Practice: Health of the Nation 2020. Melbourne, VIC: RACGP; 2020 [cited 2023 Sep 4]. Available from: www.racgp.org.au/getmedia/c2c12dae-21ed-445f-8e50-530305b0520a/Health-of-the-Nation-2020-WEB.pdf.aspx

22 Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Coronavirus (COVID-19) action plan 2021. Canberra, ACT: Department of Health and Aged Care; 2021. [cited 2022 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-action-plan (URL no longer active).

23 Australian Bureau of Statistics. COVID-19 mortality in Australia: deaths registered until 31 August 2022. Canberra, ACT: ABS; 2022 [cited 2022 Nov 22]. Available from: www.abs.gov.au/articles/covid-19-mortality-australia-deaths-registered-until-31-august-2022