Integrating shade provision into the healthy built environment agenda: the approach taken in NSW, Australia

Elizabeth King A * , Susan Thompson B and Nicola Groskops CA

B

C

Abstract

Objective: To detail the approach and progress being made by the Shade Working Goup (SWG) across health and the built environment to embed natural and built quality shade provision in places used by the community in New South Wales (NSW), Australia. Type of program or service: The NSW Skin Cancer Prevention Strategy sets a comprehensive and collaborative approach to skin cancer prevention for the state of NSW. Through the Strategy, the SWG has been promoting the benefits of shade for solar ultraviolet radiation (UVR) protection, in addition to heat mitigation, among peak bodies, governments and practitioners. Findings: With representation from health- and built environment–related disciplines, the SWG has set the foundations for raising awareness, as well as delivering education and advocacy initiatives to deepen engagement and generate evidence to better inform healthy built environment practice. Lessons learnt: The ways of working adopted by the SWG demonstrate effective collaborative principles for others to use to positively impact accepted practice across health and the built environment.Preventing skin cancer

Worldwide, there are an estimated 1.5 million cases of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers each year and more than 120 000 skin cancer–related deaths.1 Australia –as the highest rate of skin cancer in the world.2 This reflects its predominantly fair-skinned population and high levels of solar ultraviolet radiation (UVR) due to its geographical position on Earth. Melanoma and other skin cancers cost Australia approximately $1.7 billion annually3, with costs escalating due to our ageing population and increased costs for managing late-stage melanomas.

Solar ultraviolet radiation (UVR) is the cause of 95% of all skin cancers4, making skin cancer a highly preventable disease. Primary–prevention has contributed significantly to improving awareness of solar UVR, skin cancer and the need for sun protection in different settings across Australia.5 Mass media social marketing campaigns in Australia have been particularly effective, supported by settings-based sun protection programs focused on positive behavioural change.6 This is demonstrated by the declining rates of invasive melanomas in younger Australians.7 Skin cancer prevention policies including the banning of solaria8 and improvements in the Australian standards for sun protection products, including shade fabrics, sunscreen, clothing and sunglasses, are supporting these advancements.9

Aligning skin cancer prevention with healthy built environments

Healthy built environments and shade provision

A key challenge for skin cancer prevention practitioners is supporting individual behaviour change strategies that recognise the influence of broader socioeconomic, political and environmental facto–s on solar UVR exposure over the life course.10 Against the international backdrop of the World Health Organization’s Healthy Cities movement, Australia has contributed to developing this field, now widely referred to as ‘healthy built environments’.11 Both national agencies12 and those at the state level13,14 have been instrumental in advancing this work, although the role of shade in preventing skin cancer is still inconsistently acknowledged.

Quality shade is critical for solar UVR protection

Quality shade, which is a well-designed and correctly positioned combination of natural and built shade15, can reduce solar UVR exposure by up to 75%.16 This makes shade a critical component to reducing overall skin cancer risk. Shade availability and accessibility are key to shade use. Although public health professionals continue to encourage people to seek quality shade, it must be readily available across the range of outdoor spaces where children and adults live, work and play. Communities in the state of New South Wales (NSW) have been shown to overwhelmingly support government funding for more shade in public places, with the strongest support for government regulations guiding shade provision in schools.17

Australian researchers have contributed significantly to the growing body of evidence on shade provision for UVR protection.18,19 Attention within the healthy built environment sphere has focused on the benefits of shade for climate change mitigation and heat reduction.20,21 Urban greening has multiple human health and environmental sustainability benefits and is now an integral practice to shaping the built environment to promote better health.22 Further, as shade offers protection from excessive solar UVR exposure, it facilitates participation in health-supportive behaviours such as being physically active and connecting with others in outdoor settings. Including the provision of good-quality built and natural shade for skin cancer prevention is essential in creating places that support health and wellbeing.

The NSW Skin Cancer Prevention Strategy (the Strategy)23 has contributed to progress in aligning shade for solar UVR protection. A state government–led initiative, the Strategy, initially implemented in 2012, coordinates a comprehensive multisector approach to improving sun protection through policy adoption, behaviour change and shade provision strategies. The NSW Shade Working Group (SWG) operates under the auspices of the Strategy and assists in its delivery and the goal to improve access to shade. Our focus on promoting the use of shade also aligns with international guidance on health supportive places, such as the UK ‘Healthy Streets’ project. This includes ‘shade and shelter’ as one of its 10 healthy street indicators and has been adapted for use in Australia.24 Below, we outline the SWG’s approach and key activities as an exemplar for others.

The intersectoral approach taken by the Shade Working Group in NSW

Increasing planning sector awareness about the importance of skin cancer prevention strategies is a key goal of the SWG. So too is utilising intersectoral engagement to embed sun protection into the broad health, environmental and social benefits of good urban design. In particular, promoting the co-benefits of shade for both solar UVR and heat mitigation is a clear opportunity in NSW.

While a public health sun protection network has been active within NSW for more than 30 years, in 2012 the SWG was established through the Strategy to support a coordinated and strategic shade policy agenda. During the 2012–2015 phase of the Strategy, there were several SWG achievements25, including a best practice shade literature review18, updated guidelines on shade15, playground audits, community shade grants and the development of shade case studies.26

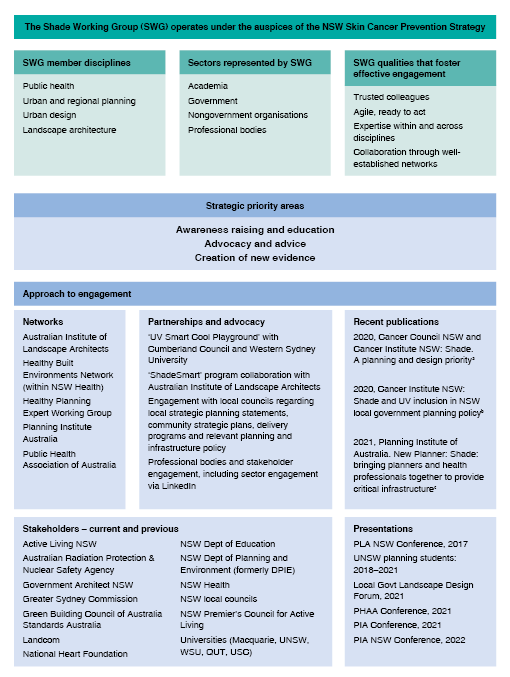

As part of the revised 2016 Strategy, the SWG invited new practitioner representation from planning and landscape architectural sectors. A work plan to drive engagement further afield, beyond the public health and cancer prevention domains, was subsequently prioritised. Figure 1 provides an overview of the qualities, ways of working and strategic priority areas of the SWG.

PLA = Parks and Leisure Australia; PHAA = Public Health Association of Australia; PIA = Planning Institute Australia

a 2020, Cancer Council NSW and Cancer Institute NSW: Shade. A planning and design priority that helps prevent skin cancer.

b 2020, Cancer Institute NSW: Shade and UV inclusion in NSW local government planning policy

c 2021, Planning Institute of Australia. New Planner: Shade: bringing planners and health professional together to provide critical infrastructure

The three SWG strategic priority areas are discussed below: awareness raising and education; advocacy and advice; and the creation of new evidence.

Awareness raising and education

The incorporation of good shade in public placemaking is promoted by the SWG through –wareness raising and educational strategies, principally aimed at championing urban shade design and increased green infrastructure to enhance sun protection. Since 2017, the SWG has engaged with 15 peak strategic and planning bodies to build relationships, seek out a common language and raise awareness of the importance of shade for solar UVR protection. The SWG has made more than 20 submissions to NSW Government public consultations to raise awareness and promote the inclusion of quality shade in key state-wide strategic and technical planning documents. Although several of these documents had previously addressed strategies to reduce urban heat and the benefits of healthy environments, few had recognised the role of shade for UVR protection. Ongoing engagement with key stakeholders and preliminary analysis of updated guidance documents reflect an increasing awareness and inclusion of shade prioritisation. For example, most recently, the NSW Draft urban design guide specifies targets for shade in public open spaces to provide protection against solar UVR.27

SWG representatives have promoted shade for UVR protection at numerous healthy built environment webinars, university lectures and network meetings, through journal articles and practitioner conference prese–tations. A succinct information resource, Shade: a planning and design priority28, showcases the co-benefits of shade. It specifically highlights solar UVR protection within the context of broader healthy built environment initiatives. Cancer Institute NSW (CINSW) has also released Sun and UV at school29, a comprehensive mix of educational resources for primary and secondary school students.

A collaborative ShadeSmart partnership was established–in 2020. The first of its kind, the partnership comprises CINSW, Cancer Council NSW (CCNSW) and the NSW Chapter of the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA). The ShadeSmart goal is to deliver a strategic skin cancer prevention program of work relevant to AILA membership and the broader community of design professionals. There are four key areas of focus: continuing professional development (CPD); influencing relevant planning and design policy and standards; promoting best-practice shade planning and design through AILA ShadeSmart awards; and conducting research into shade design and technology. A schedule of five continuing professional development modules is planned for delivery in 2022 which will be further supported by the AILA NSW Award program.

Advocacy and advice

The SWG has sought out a variety of opportunities to enhance shade availability. These include: advocacy and advice on quality shade planning to a number of local councils across NSW including Penrith City Council, Tamworth Regional Council and Wagga City Council; advocacy for improved shade as part of the North Sydney Olympic pool redesign; promoting the inclusion of shade and solar UVR effective protection in the Standards Australia development of an Urban Green Infrastructure Handbook30; and advocating to the planning profession for the framing of solar UVR as a natural hazard, mirroring other acute threats such as fire and flood.

A UV Smart and Cool demonstration project with Western Sydney University and Cumberland Council, completed in 2021, was designed to model the implementation of quality playground shade design.31

A prime opportunity arose in 2019–2020 to educate and influence NSW councils as they created their local strategic planning statements (LSPSs). CINSW and CCNSW made more than 240 submissions to 109 local councils regarding their draft LSPSs, providing specific policy suggestions for the inclusion of shade in their 20-year vision for land use. A systematic evaluation of the impact of submissions made by CINSW revealed that 74% of tailored submissions and 41% of generic submissions had achieved a degree of success, with 55 LSPSs including at least one reference to shade. The evaluation report details specific examples of shade inclusion policies for other councils to consider.32 A second phase of this approach is planned as local councils realise their LSPS vision through subsequent policies, and in the review of their community strategic plans.

New evidence

Although a lack of adequate and equitable shade availability across Greater Sydney playgrounds has been identified33, a state-wide understanding of shade availability and quality was unknown. With the imprimatur of the SWG, CINSW and Queensland University of Technology led a NSW research study to benchmark the availability and quality of shade in local council and school playgrounds. The research includes a literature review34, a report detailing more than 2500 shade audits and numerous consultations with local communities, councils and industry professionals. This is being developed into a comprehensive dataset and action tool35 designed to influence targets and improve shade design.

Conclusion

This paper details the approach and progress being made by the SWG in NSW. Four key principles underpin the group’s achievements: collaborative ways of working within and across disciplines; opportunistic engagement in policy contexts; a practitioner-focused approach to the provision of advice and support; and the need to reiterate key messages with stakeholders across a range of situations. These key principles can assist and guide other organisations in Australia and beyond working across health and the built environment. The principles offer an approach to effectively and consistently embed natural and built quality shade provision in creating places that support and nurture community wellbeing.

The SWG has achieved robust stakeholder relationships that will continue to strengthen and evolve, and while progress has been made, challenges remain. This is especially so in relation to promoting the importance of shade in providing sun protection to prevent skin cancer, along with the broader benefits of shade in reducing heat. Ensuring that shade is an integral component for professionals creating health-supportive built environments is core to future actions. Ultimately the SWG wants to see quality shade provision as a standard component of healthy built environment practice.

Acknowledgements

EK is Chair of the Shade Working Group, and ST and NG are members of the group. The authors would like to acknowledge the other current members of the group: Jan Fallding (Consultant Strategic & Social Impact Planner), Ally Hamer (Senior Skin Cancer Prevention Project Co-ordinator, CCNSW), Kylie Ide (Skin and Healthy Living Cancer Prevention Project Officer, CINSW), Andrew Turnbull (Strategic adviser, landscape architect) and Nikki Woolley (Skin and Healthy Living Cancer Prevention Portfolio Manager, CINSW). The authors also acknowledge the helpful comments of the reviewers.

This manuscript is part of a special issue focusing on skin cancer prevention. The special issue was supported by and developed in partnership with Cancer Council, and also support by the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency, the Australasian College of Dermatologists and the Australian Skin and Skin Cancer Research Centre.

References

1 International Agency for Research on Cancer. The Global Cancer Observatory; 2020. ‘Melanoma and non-melanoma estimated number of new cases and deaths in 2020, worldwide, both sexes, all ages. France: IARC; 2020 [cited 2021 Sep 2]. Available from: gco.iarc.fr/today/home

3 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Disease expenditure in Australia 2018–19. Canberra: AIHW; 2021 [cited 2022 Jan 6]. Available from: www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/9ce5ae2a-f574-4089-8d52-158abb4bdb09/Disease-expenditure-in-Australia-2018-19.pdf.aspx?inline=true

5 Walker H, Maitland C, Tabbakh T, Preston P, Wakefield M, Sinclair C. Forty years of Slip! Slop! Slap! A call to action on skin cancer prevention for Australia. Pub Health Res Pract. 2022;32(1):e31452117. Crossref

9 King, K, Javorniczky, J, Gies P., McLennan A. Changes to the Australian and New Zealand standards for sun protective products including clothing, sunglasses and shade fabrics. NIWA UV Workshop, Wellington, New Zealand: 2018 [cited 2022 Feb 1]. Available from: www.niwa.co.nz/atmosphere/uv-ozone/uv-science-workshops/2018-uv-workshop

11 Kent JL, Thompson S. Planning Australia’s healthy built environments. NY: Routledge; 2020. Crossref

12 Heart Foundation. Healthy active by design. Sydney: Heart Foundation; 2021 [cited 2022 Feb 1]. Available from: www.healthyactivebydesign.com.au/

13 NSW Department of Health. Healthy urban development checklist. Sydney: NSW Department of Health; 2009 [cited 2022 Feb 1]. Available from: www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/lcdocs/other/10375/Answers%20to%20questions%20on%20notice%20-%20NSW%20Health%20-%20Att%202.PDF

14 NSW Ministry of Health. Healthy built environment checklist: a guide for considering health in development policies, plans and proposals. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2020 [cited 2021 Sep 2]. Available from: www.health.nsw.gov.au/urbanhealth/Publications/healthy-built-enviro-check.pdf

15 Cancer Council NSW. Guidelines to shade. Sydney: Cancer Council NSW; 2013 [cited 2022 Jan 13]. Available from: www.cancercouncil.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Guidelines_to_shade_WEB2.pdf

20 Pfautsch S, Tjoelker A. The impact of surface cover and tree canopy on air temperature in Western Sydney. Sydney: Western Sydney University; 2020 [cited 2021 Sep 2]. Available from: researchdirect.westernsydney.edu.au/islandora/object/uws:57721

21 Western Sydney Regional Organisation of Councils (WSROC). Turn down the heat strategy and action plan. Sydney: WSROC; 2018 [cited 2021 Oct 4]. Available from: wsroc.com.au/media-a-resources/reports/send/3-reports/286-turn-down-the-heat-strategy-and-action-plan-2018

22 Department of Planning, Industry and Environment, Public Spaces Unit. Sydney: NSW Government [cited 2022 Jan 12]. Available from: www.dpie.nsw.gov.au/our-work/place-design-and-public-spaces

23 Cancer Institute NSW. NSW skin cancer prevention strategy. Sydney: CINSW; 2017 [cited 2022 Feb 9]. Available from: www.cancer.nsw.gov.au/getmedia/1e57459e-7bc7-4994-a005-0dc49172d6fa/CINSW-SkinStrategy-WEB.pdf

24 Healthy Streets. Healthy Streets Design Check Australia. Sydney: NSW Government; 2021 [cited 2022 Feb 9]. Available from: www.movementandplace.nsw.gov.au/resources/movement-and-place-around-world

25 Cancer Institute NSW. NSW skin cancer prevention strategy 2012–2015. Final evaluation report. Sydney: CINSW; 2015 [cited 2022 Jan 13]. Available from: www.cancer.nsw.gov.au/about-cancer/document-library/nswskin-cancer-prevention-strategy-2012-15-evalua

26 Cancer Institute NSW. How schools, councils, community groups and sporting organisations created shade: 10 case studies. Sydney: NSW Government; 2016 [cited 2022 Jan 12]. Available from: www.cancer.nsw.gov.au/getmedia/c82affbc-e3b7-4f65-8a82-87b75d283865/Short-report-A-Case-Study-approach-to-development-of-Shade-in-NSW.pdf

27 Department of Planning, Industry and Environment. Draft urban design guide: for urban design developments in NSW. Draft for discussion 2021. Sydney: NSW Government; 2021 [cited 2022 Jan 13]. Available from: shared-drupal-s3fs.s3.ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/master-test/fapub_pdf/Draft+Urban+Design+Guide_Accessible.pdf

28 NSW Shade Working Group. Shade. A planning and design priority that helps prevent skin cancer. Sydney: NSW Shade Working Group; 2019 [cited 2022 Feb 9]. Available from: www.cancercouncil.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Shade-a-planning-and-design-priority.pdf

29 Cancer Institute NSW. Sun and UV at school. Sydney: CINSW; 2020 [cited 2022 Feb 9]. Available from: www.cancer.nsw.gov.au/prevention-and-screening/preventing-cancer/preventing-skin-cancer/sun-and-uv-at-school

30 Pfautsch S, Wujeska-Krause A. Guide to climate-smart playgrounds – research findings and application. Sydney: Western Sydney University; 2021 [cited 2022 Jan 12]. Available from: researchdirect.westernsydney.edu.au/islandora/object/uws:60046

31 Cancer Institute NSW. Shade and UV inclusion in NSW local government planning policy. Sydney: CINSW; 2020 [cited 2021 Sep 2]. Available from: www.cancer.nsw.gov.au/about-cancer/document-library/shade-and-uv-inclusion-in-nsw-local-government-pla

33 Queensland University of Technology. Literature review: benchmarking shade in NSW playgrounds. Brisbane: CINSW; 2021 [cited 2022 Feb 16]. Available from: www.cancer.nsw.gov.au/getmedia/78c3b999-bec0-40ec-9964-3b7a5718faa9/Shade-Benchmarking-in-Playgrounds-Literature-Review-15-11-21.pdf

34 Cancer Institute NSW. Action tool – benchmarking shade in NSW playgrounds. Sydney: CINSW; 2021 [cited 2022 Feb 16]. Available from: www.cancer.nsw.gov.au/getmedia/a4209c82-609b-4c61-a3a7-7515f0cd8b9f/E21-19670-Action-Tool-Shade-Benchmarking-in-NSW-playgrounds-17-12-21.pdf