Disability income support design and mental illnesses: a review of Australia and Ontario

Ashley McAllister A B * , Maree Hackett A C and Stephen Leeder AA

B

C

Abstract

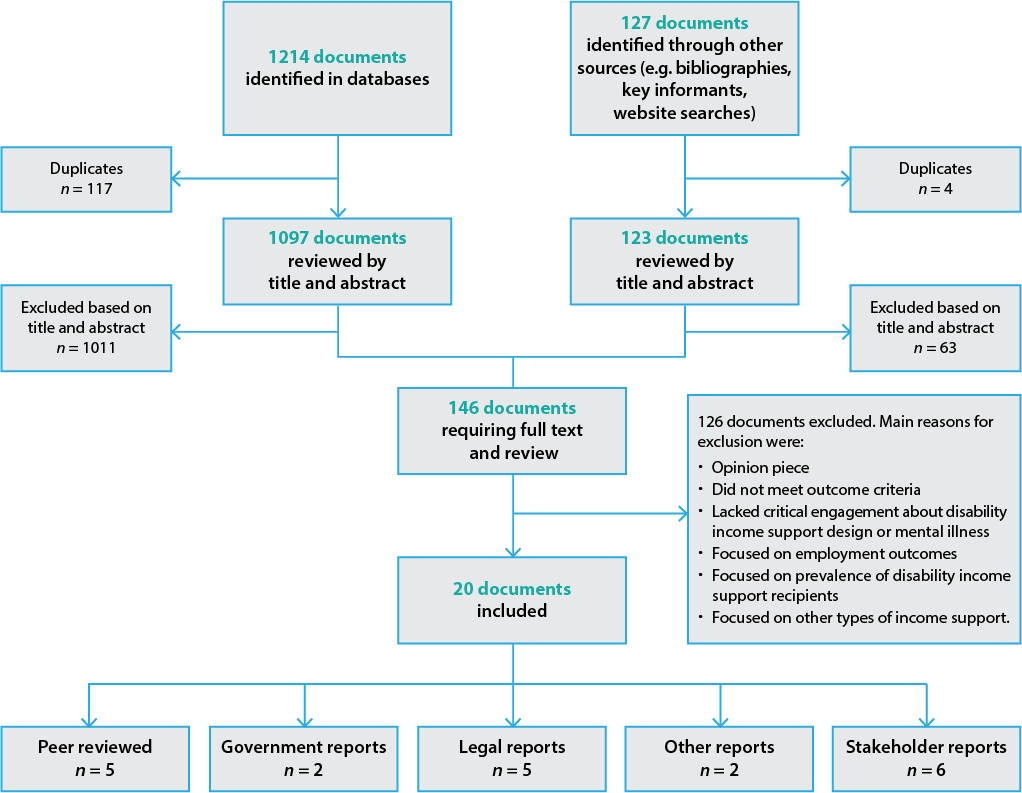

Aim:Mental illnesses have many distinctive features that make determining eligibility for disability income support challenging – for example, their fluctuating nature, invisibility and lack of diagnostic clarity. How do policy makers deal with these features when designing disability income support? More specifically, how do mental illnesses come to be considered eligible disabilities, what tools are used to assess mental illnesses for eligibility, what challenges exist in this process, and what approaches are used to address these challenges? We aimed to determine what evidence is available to policy makers in Australia and Ontario, Canada, to answer these questions. Methods: Ten electronic databases and grey literature in both jurisdictions were searched using key words, including disability income support, disability pension, mental illness, mental disability, addiction, depression and schizophrenia, for articles published between 1991 and June 2013. This yielded 1341 articles, of which 20 met the inclusion criteria and were critically appraised. Results: Limited evidence is available on disability income support design and mental illnesses in the Australian and Ontarian settings. Most of the evidence is from the grey literature and draws on case law. Many documents reviewed argued that current policy in Australia and Ontario is frequently based on negative assumptions about mental illnesses rather than evidence (either peer reviewed or in the grey literature). Problems relating to mental illnesses largely relate to interpretation of the definition of mental illness rather than the definition itself. Conclusions: The review confirmed that mental illnesses present many challenges when designing disability income support and that academic as well as grey literature, especially case law, provides insight into these challenges. More research is needed to address these challenges, and more evidence could lead to policies for those with mental illnesses that are well informed and do not reinforce societal prejudices.Introduction

Unlike other types of disability-related payments (e.g. workers’ compensation benefits) in Australia and Ontario, disability income support – payments provided by the government for those unable to work as a result of their disability – require an applicant to have little or no income. However, it is unclear in the policy documents how policy makers design and interpret eligibility criteria to distinguish between people with disabilities who are able to work and those who are unable to work, especially those with mental illnesses. We aimed to address this gap by examining the evidence in two contexts: Australia and Ontario, Canada. In Canada, the provinces are responsible for providing disability income support, and this study is limited to the province of Ontario. Unlike in other provinces, the Ontario Disability Support Program Act, 19971 explicitly excludes addiction (this has since been overturned but remains written in the Act), making it an interesting case for studying mental illnesses. These two jurisdictions also represent the most common types of model of disability income support. In Australia, the Disability Support Pension (DSP) uses an economic model in which the definition is primarily based on a person’s capacity to work. In Ontario, the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP) uses a medical model in which the definition is primarily based on a person’s medical diagnosis.

The challenges of mental illness in design of disability income support

Mental illnesses will soon be the leading cause of disability in high-income countries.2 Current estimates of the cost of mental illnesses are about A$50 billion per year in Canada and about A$20 billion per year in Australia.3,4 Unlike disability due, say, to the loss of a limb, mental illnesses can fluctuate, most lack objective diagnostic criteria, and many may be invisible to other people (i.e. there are no visual symptoms or impairment). The lack of clearly defined symptoms or impairment and diagnostic tests to prove the existence of a mental illness adds to this problem. It also distinguishes many mental illnesses from other invisible illnesses such as diabetes, where the symptoms or impairment may be invisible but a diagnostic test is available to prove that a person has the illness. The stigma associated with a diagnosis of a mental illness adds complexity to how people present with their illness, and how they ask for and receive treatment.5,6 This may raise further issues regarding whether mental illnesses and disability due to mental illnesses are considered differently from physical illness and disability due to physical illness, and how this may affect the chances of receiving disability income support in Australia and Ontario. When reviewing policy documents relating to disability income support, it is unclear how policy makers deal with these challenges or, indeed, whether they see them as an issue when designing disability income support for people with mental illnesses.

In this literature review, we aimed to determine what evidence is available to Australian and Ontarian policy makers when designing disability income support programs, especially in addressing the challenges relating to mental illnesses. Our specific questions were ‘How do mental illnesses come to be considered eligible disabilities?’, ‘What tools are used to assess mental illnesses for eligibility?’, ‘What challenges exist in this process?’ and ‘What approaches are used to address these challenges?’.

Methods

We broadly followed the Cochrane method for conducting systematic reviews7 and used the PRISMA checklist for reporting.8 The following is a description of how the articles were selected and appraised.

Search strategy

We reviewed peer-reviewed published papers and grey literature (e.g. legislation, policy documents, reports) on mental illnesses and disability income support in Australia and Ontario. We searched Embase, Informit, Medline via Ovid, ProQuest Health & Medical, PsycINFO, Scopus, Web of Knowledge, Trove via National Library of Australia (for Australian theses), and Library and Archives Canada (for Canadian theses). Grey literature, defined as any literature not produced by commercial publishers9, was identified through website searches and direct contact with relevant policy makers in both jurisdictions. To identify further studies, we searched the bibliographies of included publications; journals relating to the field, such as the Australian Social Policy Journal, the Canadian Review of Social Policy and Disability Studies Quarterly; and conference proceedings from the Australian Social Policy Conference.

Selection criteria

We chose articles that addressed specific challenges experienced by those with a mental illness in obtaining disability income support, or by policy makers when designing disability income support for people with mental illnesses.

We included articles that:

Explicitly discussed the DSP in Australia or the ODSP in Ontario

Focused on mental illnesses, making specific reference to addiction (a disputed mental illness), unipolar depression (a common mental illness) or schizophrenia (a mental illness with low incidence but high impairment), as defined in the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV)10

Were limited to individuals of working age (16–65)

Were published between 1 January 1991 (when the Australian DSP was introduced; the ODSP was not introduced until 1997) and 30 June 2013.

We excluded articles that were opinion-based documents11, were about other types of disability-related programs such as workers’ compensation benefits or employment benefits for people with disability, or were not available in English.

We assessed documents for recommendations for, or critiques of, disability income support for people with mental illnesses (e.g. defining disability, assessing disability, eligibility criteria, exclusion or inclusion of certain mental illnesses).

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently reviewed articles by title and abstract against inclusion and exclusion criteria, and selected the articles for inclusion. The full-length article was retrieved for all selected abstracts. Both reviewers completed initial data extraction and entered the data into a template. Extracted data included the author, year, type of publication, location of the program (Australia or Ontario), aim and focus of the article, key points, and strengths and limitations according to the reviewers. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. The primary reviewer (AM) completed the grey literature search, extracted the data and entered the data from the templates into a summary table.

Many tools are available for critically appraising qualitative research.12 As we extracted data, we documented specific information about the strengths and limitations of each article, using the quality appraisal instrument developed by Gallacher et al.13 as a guide, because of its flexibility in appraising documents that do not follow a typical study design.

Results

A total of 20 documents were included (see Figure 1): 5 from the academic peer-reviewed literature (Table 1) and 15 from the grey literature (Supplementary Table 2, available from: https://hdl.handle.net/2123/16497). Documents in Supplementary Table 2 were further categorised into four subtypes of grey literature: government reports, legal research and reports, other reports, and stakeholder reports. Results were presented in these groupings to identify the type of information available on design of disability income support.

| Article and jurisdiction | Aim and focus illness | Key points | Strengths and limitations | |

| Brucker14 Australia and Canada (not Ontario) | Aim: To demonstrate that target populations of public policies are based on social constructions Focus: Addiction | Strengths:

Limitations: | ||

| Carney15 Australia | Aim: To explore whether the 1990 Australian social security reforms repressed the rights of people with disabilities to income security Focus: General mental illness |

| Strengths: Limitations: | |

| Hales-Ricalis16 Ontario | Aim: To demonstrate that the ODSP addiction exclusion contributes to social stigma of people with addiction Focus: Addiction | Strengths:

Limitations: | ||

| Madden et al.17 Australia | Aim: To discuss eligibility and assessment for two major disability-related national programs in Australia, including the DSP Focus: General mental illness |

| Strengths: Limitations: | |

| Mendelson18 Australia | Aim: To explore the different rating scales available to assess psychiatric impairment in Australia Focus: General mental illness | Strengths: Limitations: |

DSP = Disability Support Pension; ODSP = Ontario Disability Support Program.

In terms of setting, most documents (11) had an Australian focus. In one article, national disability support in Australia and Canada, but not Ontario14, were compared. Nine documents had an Ontarian focus. Most documents (13) did not delineate between types of mental illnesses. Four focused specifically on addiction14,16,19,20, three on depression21,22,23 and none on schizophrenia.

Peer-reviewed research

Of the five peer-reviewed articles (Table 1), two focused on inclusion of addiction as an eligible condition in disability income support programs.14,16 Both authors argued that eligibility criteria for disability income support are based on social constructions of what the public perceives to be socially acceptable as a disability (e.g. beliefs about addiction), rather than drawing on literature about addiction that provides evidence that addiction can be debilitating and is an illness and not a choice.

Three articles critiqued the Australian Impairment Tables, a rating tool used in Australia to assess how a person’s impairment affects their capacity to work.15,17,18 These articles concluded that the tables were not a good tool for assessing eligibility, especially for people with mental illnesses. The authors raised the following concerns:

The Impairment Tables were designed to assess functioning, not to rate impairment or to be used as ‘sudden death’ criteria

There is doubt that the Impairment Tables are evidence based

Not enough consideration is given to the fluctuating nature of mental illnesses or the difficulty of predicting work impairment in the assessment process

Eligibility decisions are judgements that are influenced by external factors (i.e. economics, service traditions and societal prejudice).18

Government reports

Two Australian documents were written for government departmental purposes (Supplementary Table 2). Neither was primarily about mental illnesses, but authors of both noted the challenges associated with providing medical evidence of mental illness to prove eligibility. It was unclear whether these challenges helped or hindered people with mental illnesses in obtaining the DSP.

Legal research and reports

Five documents were categorised as legal research and reports (Supplementary Table 2). Two authors argued that, in practice, a more stringent definition of disability is applied than the written definition.20,24 Chu19, and Copes and Bisgould,20 argued that the ODSP addiction exclusion is based on assumptions about people with addictions (e.g. they are lazy and do not want to recover), rather than evidence. Both Social Security Reporter articles implied that proving eligibility is easier for a physical illness than for a mental illness.21,22 For example, in the 2011 Social Security Reporter article22, a court rejected a general practitioner’s (GP’s) evidence relating to the appellant’s mental illness, but accepted the GP’s evidence relating to the appellant’s physical illness.

Other reports

Two reports (Supplementary Table 2) were written by independent research organisations – the Centre of Full Employment and Equity, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) – and did not clearly fit into the other categories. Both reports were primarily about employment outcomes for people with mental illnesses but had sections on disability income support. Cowling25 argued that the outcomes of assessments are reliant on the assessors, not definitions or tools used. Unlike other documents, the OECD report discussed the lack of available data on this topic.26 The authors also lauded the Australian DSP assessment process for incorporating the fluctuating nature of mental illnesses.26

Stakeholder reports

Most stakeholder reports (Supplementary Table 2) were from Ontarian stakeholders and highlighted that poor access to physicians, especially mental health specialists such as psychiatrists and psychologists, makes it difficult for applicants with mental illnesses to provide adequate medical evidence to support their applications. In terms of assessment, the authors noted that evidence from GPs is sometimes discounted and that assessors apply a stricter definition of disability than the legal definition.27,28

Overall, the stakeholder reports highlighted three unique features of mental illnesses that create challenges in policy design for disability income support:

Mental illness is an umbrella term rather than a diagnosis, meaning that there is variation between different diagnoses and a spectrum within each diagnosis

The lack of relationship between the number of symptoms and the degree of impairment makes assessing work capacity difficult

Nonmedical factors (e.g. education, skills) affect the degree of impairment related to mental illnesses.

Discussion

Despite calls for greater focus on mental illnesses in policy design29-31, our results demonstrate that there is limited evidence relating to policy design for disability income support and mental illnesses in Australia and Ontario. The evidence that is available overwhelmingly suggests that disability income support, especially the assessment process, is not adequately designed for mental illnesses. Despite the variation in the type of documents, many common challenges relating to disability income support design and mental illnesses were identified, including that the policy tools (i.e. the Impairment Tables) that are available are inadequate to assist in interpreting the definition of disability, and that decisions about policy design for disability income support seem to be based more on assumptions about mental illnesses than on the current available evidence about mental illnesses – for example, the exclusion of addictions as a disability in ODSP policy, which is not evidence based. The combination of the characteristics of most mental illnesses (i.e. invisibility and difficulty of diagnosis) and the lack of evidence based tools to assess eligibility leaves too much room for assessors to rely on their own judgements when assessing mental illnesses.

Key sources of evidence in the grey literature

Limited results made it difficult to answer all of the research questions outlined in the introduction. However, the results did reveal that most documents about disability income support design and mental illnesses were found in the grey literature. This finding is significant because most systematic reviews do not include grey literature in their search strategy (e.g. see reviews by Gallacher et al.13, De Pinho Campos et al.32 and Hunter et al.33). Systematic reviews relating to policy making may fail to identify important evidence if they do not extend beyond database searching34, because evidence in the social sciences, social policy and case law may not be indexed in searchable electronic databases.12 This review indicated that grey literature is a necessary component of social science systematic reviews9,35, despite the difficulty of conducting systematic searches for such literature and assessing its quality.

In terms of types of grey literature, Supplementary Table 2 demonstrates that case law was frequently used as supporting evidence. Furthermore, results suggest that case law evidence plays an important role in design of disability income support, because decisions can set a precedent, changing the intention or interpretation of the policy. Case law and references to legislation were used to substantiate arguments, even in documents not categorised as legal documents.15,27,36The most notable example is the Tranchemontagne case that resulted in the ODSP addictions exclusion being overturned. This case was featured in many of the reviewed documents.16,19,20,27,28,36 The legal system appears to influence and monitor policy.

Limitations of case law should be acknowledged. For example, judicial decision makers base decisions on information presented in court, and therefore decisions may not be based on peer-reviewed research.

Similarities and differences between Australia and Ontario

The challenges relating to mental illnesses and disability income support were similar across the Australian and Ontarian research, suggesting that the model of disability may not be an important distinction. In the evidence reviewed, both jurisdictions seem to struggle with the unique features of mental illnesses in their approaches to design of disability income support, and documents from both settings provided little in the way of solutions.

Implications

The limited evidence suggests that current tools used to assess eligibility for disability income support leave so much room for assessors’ judgement that people with mental illnesses could easily be at a disadvantage, which could indicate inequalities in relation to people with physical illness. Developing better tools for disability income support assessors could reduce these disadvantages.

Similar systematic reviews on this topic in other jurisdictions would be beneficial. Results from these reviews could elucidate whether lack of data on this topic is context specific or an international problem.

Limitations

Determining whether evidence was anecdotal or empirical was difficult because of the lack of description of methods in many documents, including the peer-reviewed articles. Guidelines, such as those developed by Forchuk and Roberts37, could be used to ensure that documents include essential elements (e.g. details about study design). Only one document38 included disability income support assessors – those making decisions about eligibility for disability income support – in their data collection, even though many concerns were raised relating to the assessment process. Policy makers are a key resource for addressing these challenges. Future research should consider using informant interviews to learn more about policy design for disability income support from those who create the policy. Another limitation is that the review was limited to documents in the Australian and Ontario settings. It is possible that there is literature from other settings about disability income support design and mental illnesses.

Conclusion

The review confirmed that mental illnesses present many challenges when designing disability income support (e.g. fluctuating nature of the illness, impact of nonmedical factors). However, it is unclear why certain choices have been made about the definition of disability (e.g. why some illnesses are included when others, such as addiction, are not), and it remains unclear how to address the challenges associated with assessing the eligibility of people with mental illnesses for disability income support. This review contributes to these issues by providing a repository of the limited literature (identified within the parameters of this review) available to policy makers and researchers in the area of disability income support. We demonstrate that academic and grey literature (especially case law) provide valuable insights into the problems relating to disability income support design and mental illnesses in Australia and Ontario. We call for more research that focuses on how to address these challenges. More evidence on this topic could lead to policies for those with mental illnesses that are well informed and do not reinforce the societal prejudices against this already vulnerable group.

Acknowledgements

During this work, AM received a Canadian Institute of Health Research Foreign Doctoral Research Award, and MH received a National Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship 100034 (Level 2). These funding bodies had no role in the conduct or reporting of the review. We thank Anna Fraser for her contribution as a reviewer of the peer-reviewed articles. We also thank Benjamin Moffitt for his generous comments on an earlier draft.

Author contributions

AM conceived and carried out all aspects of the study design and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MH helped with study design, particularly the initial study protocol, analysis and revision of the manuscript. SL provided advice on the study design, analysis and overall manuscript preparation.

References

1 Ontario Disability Support Program Act, 1997. Toronto: Government of Ontario; 2009 [cited 2016 May 24]. Available from: www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/97o25b

3 Mental Health Commission of Canada: improving mental health outcomes for all. Ottawa: Mental Health Commission of Canada; 2013. Making the case for investing in mental health in Canada; 2013 Mar 21 [cited 2015 Oct 8]; [about 1 screen]. Available from: www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/English/document/5210/making-case-investing-mental-health-canada-backgrounder-key-facts

4 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Mental Health. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2009 [cited 2017 March 7]. Available from: www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/LookupAttach/4102.0Publication25.03.094/$File/41020_Mentalhealth.pdf

7 Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. London: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011 [cited 2015 Oct 8]. Available from: handbook.cochrane.org

8 Moyer D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9. Crossref

15 Carney T. Disability Support Pension: towards workforce opportunities or social control? University of NSW Law Journal. 1991;14(2):220–46. Article

16 Hales-Ricalis C. Lessons to be learned: the decision of the Social Benefits Tribunal in Tranchemontagne v. Ontario (Director, Disability Support Program). Critical Disability Discourse. 2010;2(2):1–16. Article

18 Mendelson G. Survey of methods for the rating of psychiatric impairment in Australia. J Law Med. 2004;11(4):446–81. PubMed

19 Chu S. Court decision extends long-term income support to those dependent on alcohol or drugs. HIV/AIDS Policy Law Rev. 2009;14(2):38–9. PubMed

20 Copes T, Bisgould L. Respondents' factum: Director, Ontario Disability Support Program and Tranchemontagne and Werbeski. Toronto: Community Legal Clinic and Legal Aid Ontario; 2010 [cited 2017 Mar 3]. Available from: www.erc.paulappleby.com/papers_docs/20100503142612/Tranchemontagne-ARCH.pdf

21 Roberts, Secretary to the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. Disability Support Pension – whether a fully documented, diagnosed condition; whether condition investigated, treated and stabilised. Social Security Reporter. 2010;12(1):1–2. Article

22 Erb, Secretary to the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. Disability Support Pension – continuing inability to work. Social Security Reporter. 2011;13(4):2–3. Article

23 Glozier N. Depression and work related disability: an introduction. Sydney: Chambers Medical Specialists; 2008 Aug [cited 2014 Jun 30]. Available from: www.cmspecialists.com.au//wp-content/uploads/Work-Related-disability-and-Depression.pdf

24 Patton L, Pooran B, Samson R. A principled approach: considering eligibility criteria for disability-related support programs through a rights-outcome lens. Toronto: Law Commission of Ontario; 2010 [cited 2014 Jun 30]. Available from: www.lco-cdo.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/disabilities_patton.pdf

25 Cowling S. The welfare to work package: creating risks for people with mental illness. Callaghan: Centre of Full Employment and Equity, University of Newcastle; 2005 [cited 2014 Jun 30]. Available from: e1.newcastle.edu.au/coffee/pubs/wp/2005/05-20.pdf

26 OECD. Sick on the job? Myths and realities about mental health and work. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2012 [cited 2014 Jun 30]. Available from: www.gamian.eu/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Miranda_OECD_sick-on-the-job_presentation_Vilnius-2013.pdf

27 Income Security Advocacy Centre. Denial by design: the Ontario Disability Support Program. Toronto: Income Security Advocacy Centre; 2003 [cited 2014 Jun 30]. Available from: www.incomesecurity.org/publications/odsp/Denial_by_Design_-_The_Ontario_Disability_Support_Program_-_2003.pdf

28 Ontario Disability Support Program Action Coalition. Access to ODSP campaign: summary of forum reports. Toronto: ODSP Action Coalition; 2003 Jan [cited 2014 Jun 30]. Available from: www.odspaction.ca/sites/odspaction.ca/files/summary_of_odsp_forums_2002.pdf

29 World Health Organization. The world health report 2001. Mental health: new understanding, new hope. Geneva: WHO; 2001 [cited 2015 Oct 8]. Available from: www.who.int/whr/2001/en/whr01_en.pdf?ua=1

37 Forchuk C, Roberts J. How to critique qualitative research articles. Can J Nurs Res. 1993;25(4):47–55. PubMed

38 Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA). Review of the tables for the assessment of work-related impairment for Disability Support Pension: advisory committee final report. Canberra: FaHCSIA; 2011 [cited 2014 Jun 30]. Available from: www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/05_2012/dsp_impairment_final_tables.pdf