Improving palliative and end-of-life care for rural and remote Australians

Sarah Wenham A * , Melissa Cumming A and Emily Saurman BA

B

Abstract

Recent reports highlight an inconsistent provision of palliative and end-of-life (palliative) care across Australia, particularly in regional, rural and remote areas. Palliative care improves quality of life and the experience of dying, and all people should have equitable access to quality needs-based care as they approach and reach the end of their lives. A palliative approach to care is crucial in rural and remote Australia where there is a reliance for such care on generalist providers amid the challenges of a limited workforce, poorer access, and vast geography. This article describes the development and implementation of the Far West NSW Palliative and End-of-Life Model of Care, a systematic solution that could drive improvement in the provision of a quality palliative approach to care and support from any clinician in a timely manner, for patients, their families and carers anywhere.

Background

Recent reports highlight an inconsistent provision of palliative and end-of-life (palliative) care across Australia, particularly in regional, rural and remote areas. They recommend that systematic solutions be developed to address the identified gaps and improve the access to and quality of palliative care and support for patients, their families and carers.1,2

Palliative care improves quality of life and the experience of dying, and all people should have equitable access to quality needs-based care as they approach and reach the end of their lives.3,4 Palliative care is provided by specialists (clinicians with advanced palliative training), generalists (other clinicians, including general practitioners), and even lay carers, making it “everyone’s business”.3-6 Specialist palliative care, where available, is most effective when it is provided early in accordance with assessed need and for complex cases.5 In Australia, 12% of those who died in 2014-15 from a known chronic or life-limiting disease received specialist palliative care in their last year of life.7 There is a reliance on generalists to provide palliative care, particularly in rural and remote regions where there is a shortage of specialists and providing quality healthcare faces well-recognised challenges of a limited workforce, poor access, and vast geography.8 These clinicians are expected to have appropriate skills, knowledge and access to training and support; however, generalist staff report that they feel ill-equipped to provide palliative care to their patients.9,10

A ‘palliative approach’ to care aims to improve quality of life for a person with a life-limiting illness by identifying and treating their physical, emotional, spiritual, cultural and social symptoms, and providing support to their families and carers by any provider.11 This approach is usually associated with aged care and generalist services, offering evidence-based processes from a specialist palliative care perspective for a generalist doctor audience. A palliative approach has been documented to improve patient care and outcomes in the last year of life, including resulting in fewer hospital admissions and an increased likelihood of dying at home.6 This palliative approach is crucial in rural and remote Australia.

Developing the Model

The Far West NSW Palliative and End-of-Life Model of Care (Model) was developed within the Far West Local Health District (FWLHD), which serves around 30 000 people of whom more than 12% identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. The FWLHD is classified as remote, covering the western third of New South Wales (NSW) – an area of approximately 200 000 km2 – and bordering three states (Queensland, South Australia, and Victoria).12 In contrast to many remote regions, a Specialist Palliative Care Service has been operating throughout the FWLHD since 1989, and provides specialist care for approximately 50% of the people who die from a known chronic or life-limiting disease each year. The existing collaboration and network across the rural and remote communities of Far West NSW provided an opportunity for innovative development of a new model to enable a consistent, high-quality palliative approach to care be extended to the other 50% of patients.

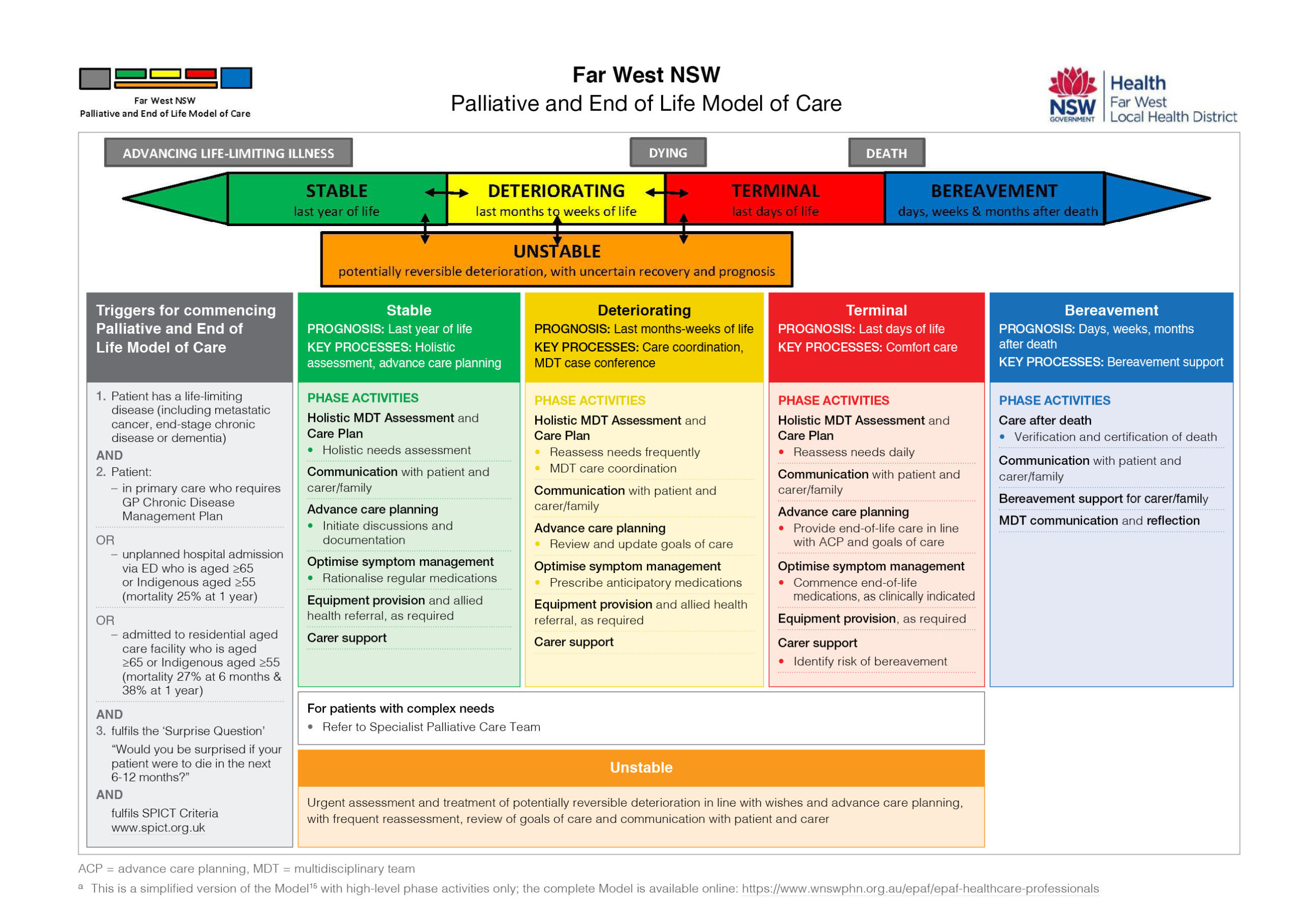

The Model was adapted from a specialist best-practice model in the UK: the North West End of Life Care Model.13 The North West Model provided a useful guide and imagery, and was a catalyst to formalise and build on established key clinical processes and adapt them for generalist services, to enable a consistent and quality palliative approach to care for anyone in need. The North West Model was adapted for the context of rural and remote Australia with the integration of the five clinically meaningful palliative care phases used to define the Australian national casemix classification (stable, unstable, deteriorating, terminal, bereavement) which made it functional in multiple care settings.14 The Model incorporates international, evidence-based best practice including care plans, case conferencing and symptom/medication management, as well as national, state and local clinical standards to enable a consistent palliative approach (Figure 1).15 It is progressively being embedded across the FWLHD.

a This is a simplified version of the Model15 with high-level phase activities only; the complete Model is available online: https://www.wnswphn.org.au/epaf/epaf-healthcare-professionals

Implementing the Model

The Model offers a systematic and responsive solution for improving palliative care. It guides the enhanced provision of comprehensive and consistent patient-centred palliative care, irrespective of diagnosis, location or care provider. Evidence-based ‘triggers’ within the Model assist earlier identification of people who would benefit from a palliative approach to care so providers can initiate care. The inclusion of prognostic indicators and clinical prompts aim to assist the transition of care between the five phases, including identifying the need to initiate appropriate referrals, diagnose dying and provide bereavement support.

Having the clinical skill to support and care for a dying person is important, but it is equally necessary to have the capacity to provide responsive and respectful care that is consistent in its application. To aid generalists’ capacity for providing palliative care, additional tools that assist clinicians to discuss, decide and document goals and other elements of palliative care for the patient as well as their family or carers were adapted and developed to accompany the Model. Tools may be added or revised with time and new evidence, or to align with particular diseases and relevant service delivery systems, such as renal or chronic care. Such adaptability allows care to be contextually responsive and fit for purpose. The Model’s transferability is dependent upon having a locally supported and collaborative system, because it functions as a universal guide applying basic principles of palliative care (i.e., needs-based holistic assessments, advance care planning, care coordination) with tools that educate and instruct (i.e. medication guide, illness trajectories).

Impact of the Model

The implementation and use of the Model are being independently evaluated. Early analyses from interviews with generalist providers suggest that the Model has: improved outcomes for patients approaching the end of their lives, as well as for their families and carers; enhanced communication, integration and collaboration between healthcare providers within and across remote communities in Far West NSW; increased clinicians’ knowledge, skill, and confidence to provide a quality palliative approach to care; and extended the capacity of the local Specialist Palliative Care Service for more complex care and support. Development of the Model into web-based resources (a shared-care patient record and an electronic resource centre) is also in progress. The complete Model and electronic links to current clinical and educational tools and resources within the Model are now available online thereby crossing clinical care boundaries and enhancing a palliative approach that is accessible to all.15 These resources enable access to shared information aiding the provision of timely, reliable, safe and appropriate palliative care that is consistent with patient wishes, by any clinician, at any time.

Conclusion

The Model is one example of a fit-for-purpose and systematic response to enhance the local provision of a palliative approach to end-of-life care in rural and remote NSW. It responds to findings that clinicians require a model to guide the delivery of palliative care and is enhanced with direction from evidence-based practice. It functions with leadership from a Specialist Palliative Care Service which can drive evidence-based care in the generalist space by sharing knowledge and tools to ensure a current, effective and supported palliative approach. Despite the challenges of rurality, and a paucity of rural and remote palliative research, the experience in FWLHD demonstrates that is it possible to provide a patient-centred, needs-based and high-quality palliative approach to care at home (or as close to home as possible), in accord with the wishes of patients and their families. The Model offers a systematic solution that could drive improvement in the provision of a quality palliative approach to care and support for patients, their families and carers anywhere.

References

1 Parliament of Victoria. Inquiry into end of life choices – final report. Victoria: Parliament of Victoria; 2016 [cited 2020 Feb 4]. Available from: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/file_uploads/LSIC_pF3XBb2L.pdf

2 NSW Auditor General. New South Wales Auditor-General’s report – performance audit: planning and evaluating palliative care services in NSW. Sydney: Audit Office NSW; 2017 [cited 2020 Feb 18]. Available from: www.audit.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/pdf-downloads/01_Palliative_Care_Full_Report.pdf

4 NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation. Palliative and end of life care – a blueprint for improvement. In: ACI Palliative Care Network Executive Committee, editor. hardcopy reference ed: NSWACI; 2017 [cited 2020 Feb 18]. Available from: www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/palliative-care-blueprint

5 Gaertner J, Siemens W, Meerpohl JJ, Antes G, Meffert C, Xander C, et al. Effect of specialist palliative care services on quality of life in adults with advanced incurable illness in hospital, hospice, or community settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2017;357:j2925. Crossref | PubMed

6 Australian Government Department of Health. National palliative care strategy 2018. Canberra: Australian Government; 2018 [cited 2020 Feb 4]. Available from: www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/national-palliative-care-strategy-2018.pdf

7 7. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Palliative care services in Australia: Archived reports and data 2015–16. Canberra: AIHW; 2017 [cited 2020 Feb 18]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/palliative-care-services/palliative-care-services-in-australia/contents/archived-data

8 Commonwealth of Australia. National strategic framework for rural and remote health. Canberra: Standing Council on Health; 2012 [cited 2020 Feb 4]. Available from: www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/national-strategic-framework-rural-remote-health

11 Department of Health. How a palliative approach can help older people being cared for at home: a booklet for older people and their families. Canberra: Australian Government; 2012 [cited 2020 Feb 4]. Available from: www1.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/palliative-agedcare-comm-familybkt-toc~palliative-agedcare-comm-familybkt-1

12 NSW Health. Far West Local Health District. Sydney: NSW Government; 2014 [cited 2020 Feb 20]. Available from: www.fwlhd.health.nsw.gov.au/

13 NHS. The North West End of Life Care Model. UK: NHS; 2011 [cited 2020 Feb 4]. Available from: www.nwcscnsenate.nhs.uk/files/2414/3280/1623/May_2015_Final_NW_eolc_model_and_good_practice_guide.pdf

15 Western NSW Primary Health Network. Palliative and End of Life Model of Care. Dubbo; phn Western NSW; 2020 [cited 2020 Feb 18]. Available from: www.wnswphn.org.au/epaf/epaf-healthcare-professionals