Impacts of long COVID on disability, function and quality of life for adults living in Australia

Danielle Hitch A B C * , Tanita Botha C D , Fisaha Tesfay C E , Sara Holton F G , Catherine M. Said H I J , Martin Hensher K , Kieva Richards

H I J , Martin Hensher K , Kieva Richards  A , Mary Rose Angeles C L , Catherine M. Bennett C , Genevieve Pepin A , Bodil Rasmussen F G M N Kelli Nicola-Richmond O

A , Mary Rose Angeles C L , Catherine M. Bennett C , Genevieve Pepin A , Bodil Rasmussen F G M N Kelli Nicola-Richmond O

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

Abstract

To describe the impact of long COVID on disability, function and quality of life among adults living in Australia.

People aged >18 years with a history of COVID-19 infection confirmed by polymerase chain reaction or rapid antigen test were eligible for this cross-sectional survey. The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 measured disability and function, and the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey assessed quality of life.

Participants (n = 121) reported significant functional impairment and reduced quality of life compared with established population norms for these outcome measures. Most (n = 104, 86%) reported clinically significant disability and participation limitations in daily activities. Mean World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 scores indicated higher levels of disability than 98% of the general population. The 36-Item Short Form Health Survey scores indicated lower quality of life across all domains, but particularly in relation to vitality and social functioning. Regression analysis found significant associations between the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 and 36-Item Short Form Health Survey scores, and vaccine dose number, comorbidities and self-rated recovery.

Long COVID is associated with significantly reduced function and quality of life, which are distinct outcomes requiring targeted assessment and intervention. The overall impact may be exacerbated in people with pre-existing comorbidities who are more susceptible to long COVID in the first place. The findings underscore the need for targeted rehabilitation and support services for people living in Australia with long COVID, and further longitudinal research to explore the long-term impact on disability and quality of life, and inform policy and healthcare service delivery.

Keywords: disability, function, long COVID, post-acute sequelae of COVID-19, quality of life, rehabilitation, SF-36, WHODAS 2.0.

Introduction

Globally, long COVID remains an important and contentious issue in global health, with debates continuing over diagnostic criteria, prevalence estimates and the mechanisms driving persistent symptoms across diverse populations (Paterson et al. 2022). For some people, COVID-19 infection leads to persistent symptoms that may occur in any body system or structures. There are no diagnostic criteria for long COVID, although the World Health Organization (WHO) describes it as ‘the continuation or development of new symptoms 3 months after the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection, with these symptoms lasting for at least 2 months with no other explanation’ (World Health Organization 2021).

Long COVID will remain a challenge for the foreseeable future, potentially affecting hundreds of thousands of people living in Australia (Parliament of Australia 2023). Prevalence ranges from 5% to 18% of acute COVID-19 infections, and varies with vaccination, access to antivirals and SARS-CoV-2 variants (Liu et al. 2021; Woldegiorgis et al. 2024). There are few Australian studies of health outcomes following COVID-19 infection, although international research consistently reports the negative impacts of long COVID on function and quality of life (QoL; Líška et al. 2022; Paterson et al. 2022; Hitch et al. 2023). Ongoing living evidence syntheses, such as those from the NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation, further underscore the evolving understanding of long COVID’s impacts (Agency for Clinical Innovation 2024).

This study describes disability, function and QoL for people living in Australia with self-reported long COVID. The research questions were:

How do disability, function and QoL for Australians with self-reported long COVID compare with previously established population norms?

What are the relationships (if any) between perceived disability, function and QoL for Australians with self-reported long COVID?

What effects (if any) do self-reported age, vaccination doses, comorbidities and recovery have on patient-reported disability, function and QoL?

Methods

Recruitment

Adults aged ≥18 years living in Australia with a polymerase chain reaction- or rapid antigen test-confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis (February 2020 to June 2022) were eligible. All potential participants confirmed they met the WHO long COVID case description (World Health Organization 2021). Recruitment used purposive and snowball methods with targeted posts to 65 social media accounts that had previously posted about long COVID. Recruitment also occurred via the research team’s long COVID professional networks and a university website (May to October 2022).

Data collection

Participants completed a 10-min, online, self-report survey comprising demographics (age, COVID diagnosis date, language, birth place, hospital admissions, vaccination status), a self-reported recovery scale, the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0 – 36-item version; Ustun and World Health Organization [WHO] 2010) and the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36; Ware and Sherbourne 1992). Comorbidities were assessed with a “yes”/“no” question and a free text box for diagnoses. A single Likert item evaluated self-rated recovery (1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = full recovery), along with a 100-point visual analogue scale (0 = no recovery, 100 = full recovery).

The WHODAS 2.0 assesses disability and function across six domains: understanding and communicating, getting around, self-care, getting along with people, life activities (i.e. household, work and/or school), and participation in society (Ustun and World Health Organization [WHO] 2010). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = no problems, 4 = extreme problems or cannot do), with lower scores indicating less disability. The 36-item version generates detailed functional information; however, Australian norms for comparison are only available for the 12-item version (Andrews et al. 2009). The norms categorise total scores as indicating no disability (0), mild disability (1–4), moderate disability (5–9) and clinically significant disability (≥10). Summative sub-scale and total scores were calculated for both the 12- and 36-item versions. The total WHODAS 2.0 36-item score was also transformed using the complex scoring approach into a disability metric (0 = no disability, 100 = full disability; Ustun and World Health Organization [WHO] 2010).

QoL and health status was measured using the SF-36 (Ware and Sherbourne 1992), where a higher score indicates better status. The scale includes eight sub-scales: physical functioning, role limitations (physical health), bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role limitations (emotional health) and mental health. Sub-scales and component scoring utilised specialised algorithms available from the Rand Corporation (RAND Corporation n.d.). Interim norms from the Australian National Household Survey (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 1996) provided comparative data.

Age, number of vaccine doses and comorbidities provided independent variables for regression analysis based on research evidence about their impact on COVID-19 severity (Romero Starke et al. 2021; Fatima et al. 2023). Self-rated recovery was also measured to explore relationships between the outcome measures and overall perceptions of health and wellbeing.

Data management and analysis

Responses were stored on the RedCap platform (Harris et al. 2019), and analysed in R (R Core Team 2021) excluding 17 incomplete surveys. Missing values were mostly confined to SF-36 Questions 3–8, were minimal and random (Little’s test, P = 0.067). This suggested low bias, which was managed with multiple imputation.

Descriptive statistics (means and proportions) summarised participants’ demographic characteristics. WHODAS12 items were extracted from the 36-item version for normative comparison, whereas SF-36 scores were directly compared with Australian norms (Andrews et al. 2009). Coding and re-coding of the WHODAS 12 items and SF-36 were undertaken, which were also recoded into 100-point scales. Average values for each domain of the WHODAS 36 items and SF-36 were not normally distributed, so Spearman’s correlation coefficient assessed for correlations between the domains on these measures. Correlations were also calculated between the WHODAS 36 items, the SF-36 general health status question and self-rated recovery scale. Correlation magnitudes were interpreted as weak (0.00–0.39), moderate (0.40–0.69), strong (0.70–0.89) or very strong (0.90–1.00; Schober et al. 2018).

Regression models were developed to investigate the effect of demographic characteristics on SF-36 and WHODAS 36-item scores. Univariate investigation identified the factors significantly associated with outcomes of interest, for inclusion in the final models to determine independent predictors. All tests were performed at a 5% level of significance.

Results

Participants’ sociodemographic and health characteristics

Surveys submitted by 121 individuals were analysed. Participants were mostly aged 36–50 years (n = 57, 47%) and Australian born (n = 100, 83%; Table 1). Most participants (n = 105, 87%) managed their acute infection in the community, and a minority (n = 50, 41%) reported comorbid conditions. Healthcare workers comprised 13% (n = 16) of the sample. Most were infected by the Omicron variant, with time since COVID-19 infection ranging from 3 to 35 months (M 8.87 months, s.d. 6.99 months).

| Variable name | Category | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <35 years | 21 (17.4) | |

| 36−50 years | 57 (47.1) | ||

| 51–65 years | 40 (33.1) | ||

| >66 years | 3 (2.5) | ||

| Country of birth | Australia | 100 (82.6) | |

| Elsewhere | 21 (17.4) | ||

| Language spoken in daily life | English | 120 (99.2) | |

| Language other than English | 1 (0.08) | ||

| Comorbid condition | Yes | 50 (41.3) | |

| Place of COVID-19 treatment | In hospital (including ICU admission) | 7 (5.8) | |

| In hospital (without ICU admission) | 9 (7.4) | ||

| In the community | 105 (86.8) | ||

| Place of residence | Australia Capital Territory | 5 (4.1) | |

| New South Wales | 29 (24.0) | ||

| Northern Territory | 1 (0.8) | ||

| Queensland | 18 (14.9) | ||

| South Australia | 9 (7.4) | ||

| Tasmania | 3 (2.5) | ||

| Victoria | 49 (40.5) | ||

| Western Australia | 7 (5.8) | ||

| Working as a health worker | Yes | 16 (13.2) |

ICU, intensive care unit.

Patient-reported disability, function and QoL

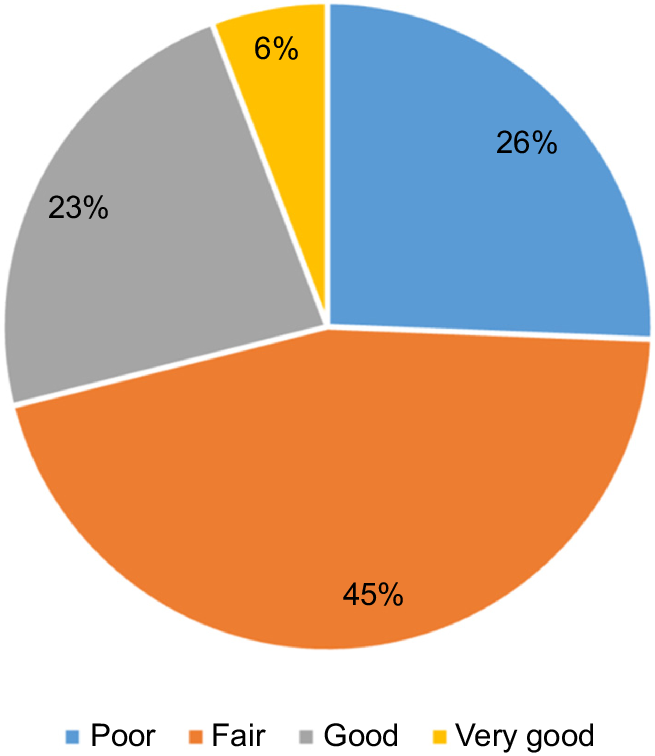

Most participants reported their recovery as ‘fair’ (n = 55, 45%), which aligned with visual analogue scale scores (M 35.78, s.d. 6.30; Fig. 1). The Likert and analogue scales strongly correlated (r = 0.81, P < 0.001), with no participants reporting complete recoveries.

Disability and Function

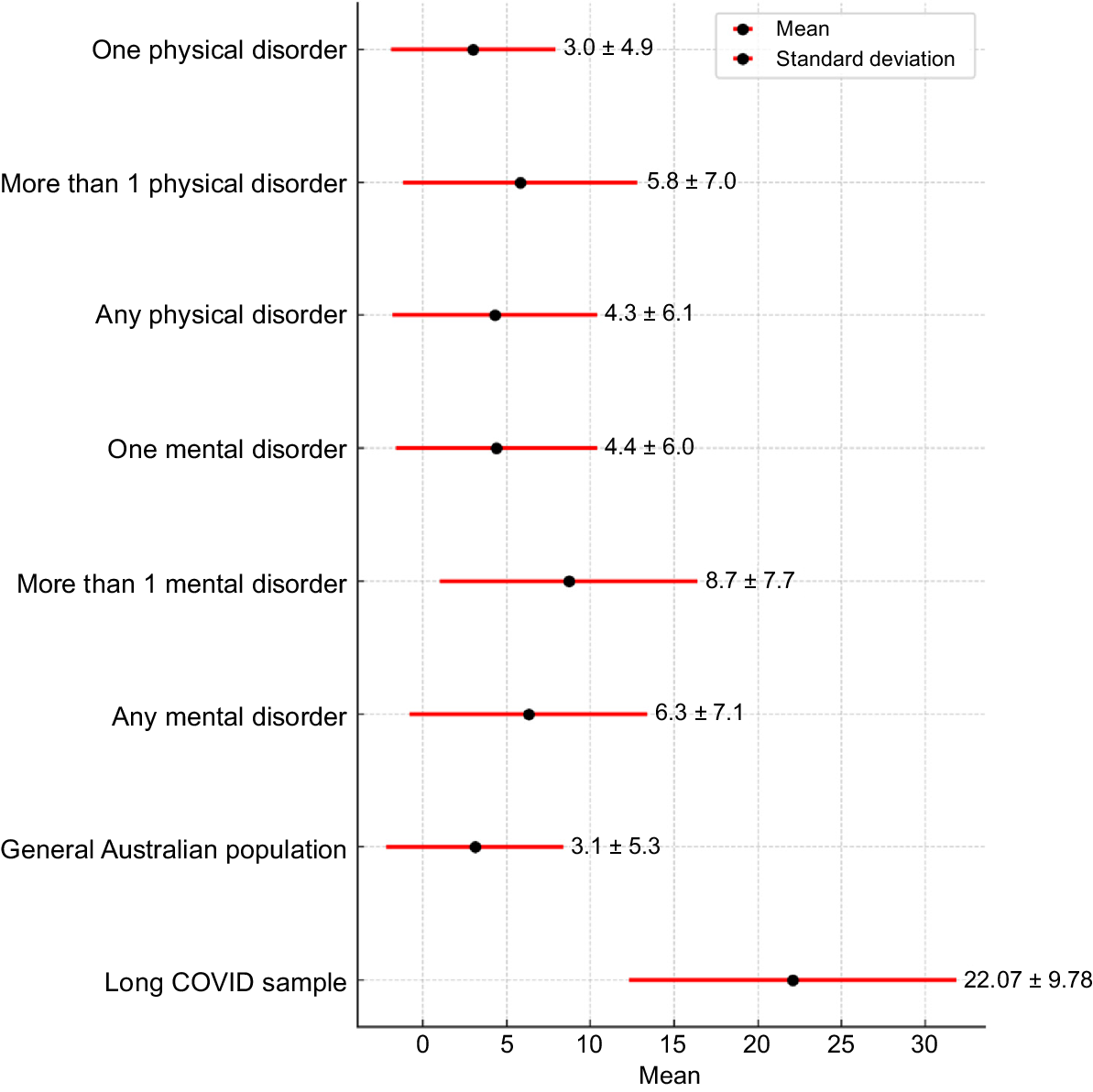

WHODAS 36-item subscale scores varied widely (Table 2), with all participants reporting mild, moderate, severe or extreme disability on at least one subscale. The disability metric was 69 out of 100, indicating participants experienced greater disability than 98% of the general population.

| WHODAS scores (scale range) | Mean (s.d.) | Range of responses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding and comprehension (0–24) | 9.7 (5.3) | 0–24 | |

| Getting around (0–20) | 9.6 (5.0) | 0–20 | |

| Self-care (0–16) | 3.9 (3.6) | 0–16 | |

| Getting along with people (0–20) | 8.6 (5.1) | 0–20 | |

| Life activities (0–16) | 10.3 (4.4) | 0–16 | |

| Work/school (n = 94) (0–16) | 11.0 (4.8) | 0–16 | |

| Participating in society (0–32) | 18.2 (7.3) | 0–32 | |

| WHODAS 36 items total | 68.9 (27.4) | 14–124 |

s.d., standard deviation; WHODAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule.

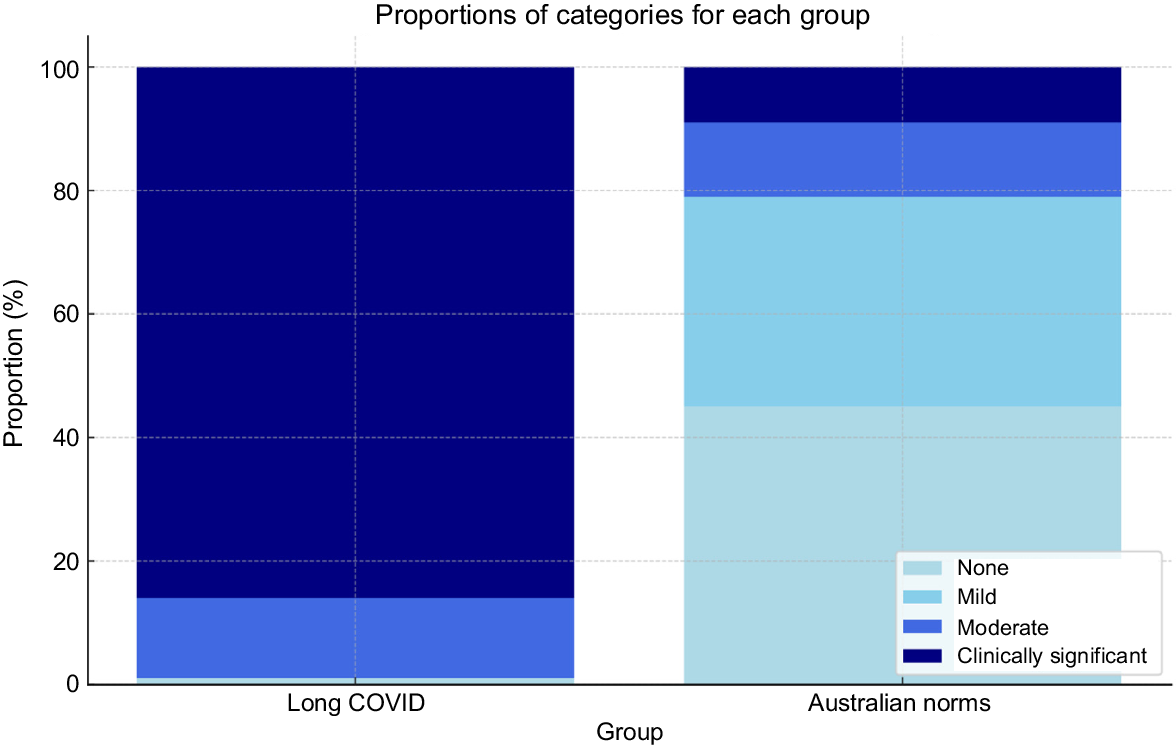

Participants experienced difficulties with daily activities on M 26.7 (±6.6) days per month, and had to reduce participation on M 19.70 (±11.56) days per month. They were totally unable to complete daily activities on M 17.95 (±11.95) days per month. Activities related to household duties, work/school and participating in society were the most difficult, whereas self-care caused the least problems. WHODAS 12-item scores were higher than all categories of Australian population norms reported by Andrews et al. (2009), indicating generally higher levels of disability (Fig. 2).

Australian norm and long COVID sample World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0) means and standard deviations.

Most participants (86%) reported clinically significant disability, in comparison with 9% of the general Australian population (see Fig. 3).

QoL

SF-36 subscale scores also varied significantly (Table 3). Participants generally reported worse health and wellbeing than the general population. Vitality and social functioning caused the most difficulties, whereas pain and emotional wellbeing were less problematic. Total SF-36 scores were 23 points below the Australian norm.

| SF-36 sub-scale scores | Mean (s.d.) | Response range A | Australian norms (s.d.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 34.7 (24.6) | 0–95 | 83.6 (23.4) | |

| Role limitations due to physical health | 3.5 (12.6) | 0–100 | 79.7 (35.1) | |

| Role limitations due to emotional health | 30.6 (43.2) | 0–100 | 83.7 (30.9) | |

| Vitality | 13.5 (14.7) | 0–70 | 63.9 (19.4) | |

| Emotional wellbeing | 51.9 (20.1) | 0–92 | 75.7 (16.4) | |

| Social functioning | 26.8 (22.8) | 0–100 | 84.6 (22.2) | |

| Pain | 44.8 (25.0) | 0–100 | 76.9 (25.2) | |

| General health | 36.0 (18.4) | 0–90 | 71.5 (20.8) |

Relationship between perceived recovery, function and QoL

Self-rated recovery (visual analogue) moderately correlated with WHODAS 36 items work/school (r = −0.69), mobility (r = −0.66), societal participation (r = −0.61) and life activities (r = −0.59) subscales (all P < 0.001), and total WHODAS 12-item (r = −0.67) and WHODAS 36-item (r = −0.66) scores. However, other subscales were weakly correlated with self-rated recovery.

The SF-36 general health item was weakly correlated with all WHODAS sub-scales, WHODAS 12-item and WHODAS 36-item total scores, and all SF-36 sub-scales. The SF-36 social functioning (r = 0.56, P < 0.001), energy/fatigue (r = 0.63, P < 0.001) and physical functioning (r = 0.53, P < 0.001) sub-scales moderately correlated with self-rated recovery.

The regression analyses for the SF-36 and WHODAS scales, respectively, are shown in Tables 4 and 5. Pre-existing comorbidities were not a major predictor of QoL, disability or function. The only aspect of QoL predicted by age was role limitations caused by emotional problems, with older participants reporting lower QoL. However, age was associated with less disability on the getting around, self-care and household activities WHODAS 36-item subscales.

| Estimate (s.e.) | P-value | R squared | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | ||||

| Age | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.60 | 0.34 | |

| Comorbidities yes (base – N0) | −5.7 (3.9) | 0.15 | ||

| Vax 3 times (base – vax 2 times) | −12.6 (4.9) | 0.01* | ||

| Vax 4 or more (base – vax 2 times) | −6.4 (5.1) | 0.22 | ||

| Recovery VAS | 0.5 (0.1) | <0.001* | ||

| Role limitations – physical health | ||||

| Age | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.55 | ||

| Vax 3 times (base – vax 2 times) | −5.0 (2.8) | 0.08 | 0.12 | |

| Vax ≥4 (base – vax 2 times) | −1.3 (3.0) | 0.68 | ||

| Recovery VAS | 0.2 (0.0) | <0.001* | ||

| Role limitations – emotional problems | ||||

| Age | −0.8 (0.4) | 0.03* | 0.13 | |

| Vax 3 times (base – vax 2 times) | 31.8 (9.3) | <0.001* | ||

| Vax ≥4 (base – vax 2 times) | 37.5 (9.9) | <0.001* | ||

| Energy fatigue | ||||

| Age | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.09 | 0.33 | |

| Recovery VAS | 0.3 (0.0) | <0.001* | ||

| Emotional wellbeing | ||||

| Age | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.19 | 0.15 | |

| Vax 3 times (base – vax 2 times) | 11.8 (4.3) | 0.007* | ||

| Vax ≥4 (base – vax 2 times) | 11.5 (4.6) | 0.014* | ||

| Recovery VAS | 0.3 (0.1) | <0.001* | ||

| Social functioning | ||||

| Age | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.20 | 0.39 | |

| Comorbidities yes (base – N0) | 4.0 (3.3) | 0.24 | ||

| Recovery VAS | 0.5 (0.1) | <0.001* | ||

| Pain | ||||

| Age | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.97 | 0.16 | |

| Vax 3 times (base – vax 2 times) | 12.4 (5.3) | 0.02* | ||

| Vax ≥4 (base – vax 2 times) | 6.3 (5.7) | 0.27 | ||

| Recovery VAS | 0.4 (0.1) | <0.001* | ||

| General health | ||||

| Age | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.60 | 0.29 | |

| Recovery VAS | 0.5 (0.1) | <0.001* |

*, stastically significant; s.e., standard error; VAX, vaccination status; VAS, visual analogue scale.

| Estimate (s.e.) | P-value | R squared | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding and communicating | ||||

| Age | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.74 | 0.22 | |

| Recovery VAS | −0.10 (0.0) | <0.001* | ||

| Getting around | ||||

| Age | −0.09 (0.0) | 0.004* | 0.48 | |

| Recovery VAS | −0.12 (0.0) | <0.001* | ||

| Self-care | ||||

| Age | −0.07 (0.0) | 0.008* | 0.22 | |

| Recovery VAS | −0.05 (0.0) | <0.001* | ||

| Getting along with people | ||||

| Age | −0.06 (0.0) | 0.16 | 0.22 | |

| Recovery VAS | −0.09 (0.0) | <0.001* | ||

| Life activities – full list | ||||

| Age | −0.3 (0.1) | <0.001* | 0.42 | |

| Vax 3 times (base – vax 2 times) | 5.9 (1.6) | <0.001* | ||

| Vax ≥4 or more (base – vax 2 times) | 6.3 (1.7) | <0.001* | ||

| Recovery VAS | −0.1 (0.0) | <0.001* | ||

| Life activities – (just la1 to la4) | ||||

| Age | −0.1 (0.0) | 0.03* | 0.41 | |

| Vax 3 times | 1.7 (0.8) | 0.03* | ||

| Vax ≥4 | 2.0 (0.9) | 0.02* | ||

| Recovery VAS | −0.1 (0.0) | <0.001* | ||

| Life activities – work/school | ||||

| Age | −0.0 (0.0) | 0.41 | 0.55 | |

| Vax 3 times | 2.4 (0.9) | 0.01* | ||

| Vax ≥4 | 2.5 (01.0) | 0.01* | ||

| Recovery VAS | −0.1 (0.0) | <0.001* | ||

| Participation in society | ||||

| Age | −0.1 (0.1) | 0.12 | 0.40 | |

| Recovery VAS | −0.2 (0.0) | <0.001* | ||

| WHODAS 36-item total | ||||

| Age | −0.6 (0.2) | 0.001* | 0.51 | |

| Recovery VAS | −0.7 (0.1) | <0.001* |

*, stastically significant; s.e., standard error; VAX, vaccination status; VAS, visual analogue scale; WHODAS, World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule.

Three vaccine doses (i.e. full vaccination plus one booster) correlated with worse physical function and greater role limitations due to emotional health than two doses only. Conversely, four or more vaccine doses were predictive of better emotional wellbeing and fewer role limitations due to emotional problems, but also greater difficulties with household and work/school activities. Self-rated recovery consistently and significantly predicted all WHODAS 36-item and SF-36 dimensions.

R squared values for the SF-36 domains ranged from 0.10 to 0.39, indicating a moderate ability to explain variance in QoL. However, values for the WHODAS domains ranged from 0.22 to 0.55, suggesting the sociodemographic factors analysed were more influential on disability and function.

Discussion

Australian adults with long COVID reported significant functional impairment and reduced QoL compared with norms. Most had clinically significant disability and limited daily participation, especially in relation to vitality, household duties, work/school and societal roles. However, they experienced fewer problems with self-care, pain and emotional wellbeing. Disability and QoL were weakly correlated, with regression analyses indicating complex sociodemographic influences. Self-rated recovery also moderately correlated with vitality, physical function and community participation.

Various comorbidities are known risk factors for severe acute COVID-19 and subsequent long COVID, including respiratory disorders and recent cancer diagnosis (Liu et al. 2020). However, there is little evidence about their influence on long COVID severity or duration. In this study, comorbidity did not significantly predict disability or QoL. Therefore, the relationship between long COVID and comorbidities may be more nuanced than causative.

Disability and QoL outcomes were weakly correlated, with sociodemographic factors playing variable predictive roles. In a multinational study (including Australian participants), Bonsaksen et al. (2022) found age group, gender, education level, employment and/or marital status were not associated with self-identified long COVID. Concepts of function and QoL are often used interchangeably, but significant disability can co-exist with excellent QoL (and vice versa). Functional outcome measures provide a tangible basis for management plans, whereas QoL measures assess the subjective impact of health conditions (Whitcomb 2011). Therefore, longitudinal monitoring of both these outcomes with psychometrically sound measures is crucial to understanding the impacts of long COVID.

Self-rated recovery, which reflects perceived progress, strongly predicted both functional (e.g. work/school, mobility) and QoL outcomes (e.g. vitality), but was only weakly related to perceptions of overall health. This suggests self-rated recovery better captures long COVID’s pervasive impact, meaning this measure is better suited to guiding personalised management (Bierbauer et al. 2022; Huijts et al. 2023). A single self-reported recovery item can effectively capture patient perceptions of progress, with previous research indicating visual analogue scales are preferred for capturing subtle shifts in health and wellbeing (Huijts et al. 2023).

Participants reported severe deficits in vitality and functional limitations, comparable to other conditions, such as stroke, rheumatoid arthritis and Parkinson’s disease (Twomey et al. 2022). Problematic daily activities are more cognitively and physically demanding, and often occur in community spaces. Current long COVID rehabilitation literature focuses on regaining physical function (Sari and Wijaya 2023), but these findings emphasise its impact on more complex daily activities. Rehabilitation must therefore prioritise both fatigue and functional recovery to maximise recovery.

Self-reported vaccination status showed variable associations with outcomes in this observational study, likely reflecting complex confounding factors, including vaccination priority, uptake timing, pre-existing disability levels and self-reported data inaccuracies. The relationship may be further confounded by vaccine dose number, which related to the timing of participants entering the study and the variant responsible for their infection, all of which are predictors of long COVID severity. Additionally, the cross-sectional, observational design limits causal inferences, particularly for vaccine-related findings, underscoring the need for larger, longitudinal studies to confirm associations. Higher emotional wellbeing scores from participants receiving more doses occurred against a generally poorer functional background, and the negative association between age and role limitations due to emotional problems. This may indicate over-representation by participants already adjusted to existing disability or ageing among the more vaccinated participants. Given the modest sample size (n = 121), and reliance on self-reported vaccination and infection details, these findings should be interpreted cautiously to avoid misinforming public health messaging on vaccination benefits.

This study has several limitations, including no matched control group, and therefore, the representativeness of the sample is uncertain, and the background rates for shifts in these measures in the pandemic setting is not known. Recruiting people with self-identified long COVID may also have over-selected people predisposed to poorer outcomes or with increased concern or less tolerance of their situation. Relying on self-report for other demographic variables, such as vaccination status, may also introduce inaccuracy into the analysis if these details are misremembered. Although the use of social media in recruitment may have increased exposure of the study, it may have biased the sample to people familiar with this technology. Participants reported less pre-existing comorbidity (41%) than the general Australian population (47%; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2023), but we had no data on pre-existing levels of disability to contextualise the long COVID outcomes. Disability and QoL were measured at a single time point, and this varied between participants. Equivocal evidence existed around the impact of gender when this study was designed, and its influence requires further investigation.

In conclusion, long COVID significantly impaired disability and QoL in study participants. Incorporating a self-rated recovery item, functional and QoL measures in the ongoing monitoring of long COVID patients would enable individualised management plans. Intervention should also prioritise fatigue management and more complex daily activities, such as domestic, community and social tasks. More longitudinal research, including gender analysis, is urgently required to better understand the risk, duration and nuanced impact of long COVID on daily life for people living in Australia.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, DH, upon reasonable request.

Declaration of funding

This project received funding from the Institute of Health Transformation at Deakin University via the Category 1 Seed Grant scheme.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the unceded lands, skies and waterways on which this work was produced. We pay our deep respect to the Ancestors and Elders of Muwinina, Palawa, Wurundjeri and Wadawurrung country in recognition of the deep history and culture of these lands. This project received funding from the Institute of Health Transformation at Deakin University via the Category 1 Seed Grant scheme.

References

Agency for Clinical Innovation (2024) Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (long COVID). Available at https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/statewide-programs/critical-intelligence-unit/post-acute-sequelae [accessed 11 July 2025]

Andrews G, Kemp A, Sunderland M, Von Korff M, Ustun TB (2009) Normative data for the 12 Item WHO disability assessment Schedule 2.0. PLoS ONE 4(12), e8343.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2023) Chronic conditions and multimorbidity. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/chronic-conditions-and-multimorbidity

Bierbauer W, Lüscher J, Scholz U (2022) Illness perceptions in long-COVID: a cross-sectional analysis in adults. Cogent Psychology 9, 2105007.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bonsaksen T, Leung J, Price D, Ruffolo M, Lamph G, Kabelenga I, Thygesen H, Geirdal AØ (2022) Self-reported long COVID in the general population: sociodemographic and health correlates in a cross-national sample. Life 12(6), 901.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Fatima S, Ismail M, Ejaz T, Shah Z, Fatima S, Shahzaib M, Jafri HM (2023) Association between long COVID and vaccination: a 12-month follow-up study in a low- to middle-income country. PLoS ONE 18(11), e0294780.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, Duda SN, behalf of the REDCap Consortium (2019) The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 95, 103208.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hitch D, Deféin E, Lloyd M, Rasmussen B, Haines K, Garnys E (2023) Beyond the case numbers: social determinants and contextual factors in patient narratives of recovery from COVID-19. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 47(1), 100002.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Huijts T, Gage Witvliet M, Balaj M, Andreas Eikemo T (2023) Assessing the long-term health impact of COVID-19: the importance of using self-reported health measures. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 51, 645-647.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Líška D, Liptaková E, Babičová A, Batalik L, Baňárová PS, Dobrodenková S (2022) What is the quality of life in patients with long COVID compared to a healthy control group? Frontiers in Public Health 10, 975992.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Liu H, Chen S, Liu M, Nie H, Lu H (2020) Comorbid chronic diseases are strongly correlated with disease severity among COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging and Disease 11, 668-678.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Liu B, Jayasundara D, Pye V, Dobbins T, Dore GJ, Matthews G, Kaldor J, Spokes P (2021) Whole of population-based cohort study of recovery time from COVID-19 in New South Wales Australia. Lancet Regional Health - Western Pacific 12, 100193.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Paterson C, Davis D, Roche M, Bissett B, Roberts C, Turner M, Baldock E, Mitchell I (2022) What are the long-term holistic health consequences of COVID-19 among survivors? An umbrella systematic review. Journal of Medical Virology 94(12), 5653-5668.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

RAND Corporation (n.d.) 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) Scoring Instructions. Available at https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/mos/36-item-short-form/scoring.html

Romero Starke K, Reissig D, Petereit-Haack G, Schmauder S, Nienhaus A, Seidler A (2021) The isolated effect of age on the risk of COVID-19 severe outcomes: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ Global Health 6, e006434.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Sari DM, Wijaya LCG (2023) General rehabilitation for the post-COVID-19 condition: a narrative review. Annals of Thoracic Medicine 18(1), 10-14.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Schober P, Boer C, Schwarte LA (2018) Correlation coefficients: appropriate use and interpretation. Anesthesia & Analgesia 126(5), 1763-1768.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Twomey R, DeMars J, Franklin K, Culos-Reed SN, Weatherald J, Wrightson JG (2022) Chronic fatigue and postexertional malaise in people living with Long COVID: an observational study. Physical Therapy 102, pzac005.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ware JE, Jr., Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30(6), 473-483.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Whitcomb J (2011) Functional status versus quality of life: where does the evidence lead us? Advances in Nursing Science 34(2), 97-105.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Woldegiorgis M, Cadby G, Ngeh S, Korda RJ, Armstrong PK, Maticevic J, Knight P, Jardine A, Bloomfield L, Effler PV (2024) Long COVID in a highly vaccinated population infected during a SARS-CoV-2 Omicron wave: a cross-sectional survey. Medical Journal of Australia 220(6), 323-330.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |