Adolescent health presentations to Victorian general practice: a descriptive study using electronic medical records

Ronnen Leizerovitz A # , Ian Williams A # * , Adrian Laughlin A Lena Sanci A

A Lena Sanci A

A

Abstract

Although most young Australians visit their general practitioner at least once a year, discrepancies remain between healthcare need and healthcare support in this group. A detailed contemporary understanding of youth presentations to general practice is needed, given that the last comprehensive investigation into Australian adolescent encounters with primary care is now over two decades old. The aim of this study is to describe rates of presentation and reasons for visit among young people in Victorian primary care using data extracted from electronic medical records.

A retrospective descriptive study of de-identified electronic medical records data from >22,000 adolescents aged 10–24 years who presented to Victorian general practice in 2019 was undertaken.

The overall mean attendance rate of young people was 2.89 visits/patient per year, with rates highest amongst older patients, females and those in regional localities. Young people presented most frequently for physical (biomedical) concerns (such as respiratory, skin and general physical complaints), and psychological (mental health) reasons for visit.

The study addresses a significant gap in our understanding of the role of general practice for young Australians. Although physical problems continue to predominate among Australian adolescents’ reasons for visit to general practice, psychological presentations occur much more frequently than estimated in past studies. This study also demonstrates that general practice electronic medical records data can be harnessed to provide a meaningful description of primary care activity.

Keywords: adolescent, electronic medical records, EMR, general practice research, mental health, primary care, reason for visit, youth.

Introduction

Adolescence is a critical developmental stage in which the foundations of future health are established. This phase is characterised by rapid physical, neurocognitive, emotional and social changes, including those associated with puberty, along with increased independence and personal autonomy (Patton et al. 2016). Although adolescence has often been considered a period of relatively good health, the risks to health and wellbeing in this group are significant. Globally, young people are burdened disproportionately by mental disorders, injury (both non-accidental and intentional), sexually transmitted illnesses and pregnancy-related complications (Patton et al. 2009; Sawyer et al. 2012). Furthermore, the establishment of health risk behaviours during adolescence, among them smoking, alcohol abuse, substance use, poor diet and sedentary lifestyle, endangers both young people’s current health status and their health trajectories into adulthood. As such, investment in adolescent health yields important health and economic benefits, both for individuals and their communities (Patton et al. 2016).

In Australia, various health policy frameworks exist to address the specific challenges of adolescence, all of which emphasise the importance of primary care and prevention (NSW Ministry of Health 2017; Western Australian Department of Health 2018; Victoria State Government 2022). The frontline of Australia’s primary care workforce is general practice, which is well-placed to manage risk and promote healthy behaviours among the nation’s youth. Approximately 80% of young people visit a general practitioner (GP) at least once a year, and young people nominate GPs as their preferred healthcare provider when seeking help (Booth et al. 2004; Britt et al. 2016).

Nevertheless, evidence suggests that key healthcare needs of young people may not be fully addressed by Australian primary care. In the most detailed and wide-ranging investigation into Australian adolescent encounters with primary care, Booth et al. (2008) examined adolescent (age 10–19 years) encounters in general practice between 1998 and 2004, and found adolescents to have the lowest rates of contact with general practice of any age bracket in Australia (Booth et al. 2008). Furthermore, presentations and interventions relating to mental health, preventive care and health promotion were found to be highly infrequent (Booth et al. 2008). These findings sit alongside more contemporary trends showing a steady increase in emergency department presentations among Australian youth, driven largely by a rise in acute mental health problems (Hiscock et al. 2018). Although apparent discrepancies between healthcare need and healthcare support among youth may be related to the well-established barriers young people face in accessing primary care (including fears over confidentiality, lack of youth-friendly services, poor service knowledge and cost; Booth et al. 2004; Tylee et al. 2007), there remains an imperative to identify and address issues of unmet healthcare need among young Australians.

To address concerns of unmet healthcare need among adolescents in Australian primary care, a detailed understanding of their presentations to general practice is essential. However, with data from the Booth et al. (2008) study now two decades old, there is a clear need to revisit the question of adolescent health presentations to general practice in a contemporary setting. Moreover, the national, annual paper-based GP survey on which this study relied (the Bettering the Evaluation of Care and Health program (BEACH)1) has since been discontinued, and new methods are required for large-scale insights into general practice activity.

While the discontinuation of the BEACH program has left a large gap in data collection in Australian primary care, a growing interest has emerged in the use of electronic medical records (EMRs) as a data source for health research. GPs in Australia rely almost exclusively on EMRs created routinely during clinical practice to record patient encounter information, including history, examination, pathology, prescriptions and other treatments, generating rich data that may be later used for anonymised, secondary research purposes (Canaway et al. 2019). Benefits of EMR-based research include increased efficiency of data collection and access to large samples, although concerns remain over data quality, completeness and fitness for purpose (Canaway et al. 2019).

In this study, we examined detailed, large-volume EMR data to describe the nature of adolescent health presentations to Victorian general practice. Specifically, we sought to: (1) determine rates of attendance, and (2) frequencies of various presentations (reasons for visit (RFVs)) among adolescents and young adults aged 10–24 years in these primary care settings. In doing so, we aim to provide updated insights into health presentations of Australian young people in primary care, while exploring the advantages and limitations of using clinical EMR data to examine contemporary health research questions.

Methods

Data collection

A retrospective, quantitative descriptive study was undertaken using de-identified data from EMRs of adolescent patients from a sample of Australian general practices across a single year. EMR data (including reasons for presentation, diagnoses, prescriptions issued, pathology and imaging ordered, Medicare item billed, and patient demographic data) were extracted from the records of 29 consenting Victorian GP clinics participating in the ‘Primary Care Audit, Teaching and Research Open Network’ (Patron) program (Manski-Nankervis et al. 2024). Patron is a research initiative of the University of Melbourne’s Department of General Practice and Primary Care that aims to make better use of existing primary care data to improve knowledge, medical education, policy and the way medical care is delivered (University of Melbourne Department of General Practice and Primary Care 2024). At the time of the present study, data extracts from the three most commonly used EMR software systems in Australia (Best Practice, Medical Director and ZedMed) were not harmonised in the Patron dataset, and hence only practices using Best Practice were included for this analysis.

Data management

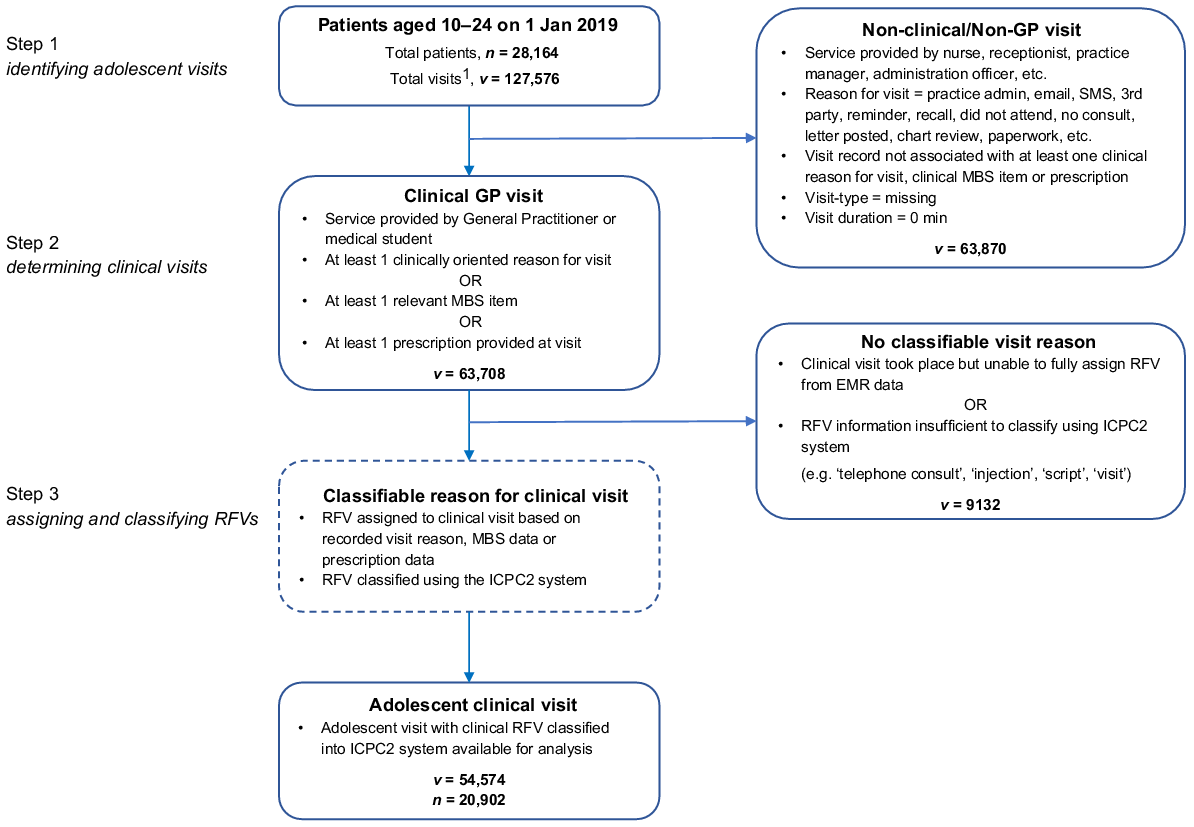

To prepare data for examination and explore key research questions, data management proceeded through three steps (see Fig. 1): (1) identifying which visits to participating GP clinics across the year 2019 were made by adolescent patients; (2) determining which encounters in the EMR from among this patient group were for actual clinical visits; and (3) assigning RFVs to each of these identified clinical visits and classifying them according to the International Classification for Primary Care-2 (ICPC-2; WHO 2005) classification system to calculate the relative frequency of RFVs.

Steps followed to identify, determine and classify adolescent clinical presentations to GP clinics across 2019.

From the subset of enrolled practices using Best Practice, data were obtained for all active adolescent patients (aged between 10 and 24 years inclusive on 1 January 2019) who had visited their GP at least once within the year 2019. For each patient, multiple visits to their GP may have been recorded across the 12-month period, with multiple datapoints captured at each visit to record relevant details, such as patient demographics, visit reason/s, tests conducted, medications prescribed and item numbers from the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS; a list of medical services for which subsidies are available through Australia’s government-funded, universal health insurance scheme), which code for the type and cost of the consultation (further details on the EMR data structure accessible through Patron are available on the program’s official website (University of Melbourne Department of General Practice and Primary Care 2024).

The central focus of this study was to examine the nature of clinical GP visits by young people to primary care. However, not all entries captured in the patient EMR relate to clinical visits (e.g. administrative and clinical management activities, such as file reviews, clerical tasks and documented failures of attendance may all be captured). Hence, it was necessary to identify which entries in patients’ data records reflected actual clinical visits (i.e. patient attended GP clinic seeking support for an identified clinical need).

The target encounters for this study were those conducted by a GP or medical student (overseen by a GP) and classified as clinical in nature. We followed a systematic approach to determine which visits in the dataset met these criteria (see Fig. 2). For example, visits that were undertaken by practice support staff or by providers other than GPs or medical students were dropped from the dataset, as were types of encounters considered non-clinical (e.g. email sent; patient did not attend; MBS or prescription fields indicated visit was not clinical; visit duration of 0 min).

A key goal of the study was to determine the clinical purpose (i.e. the RFV) for each adolescent visit. When consulting with patients, GPs typically record a RFV in the EMR (using a combination of drop-down menus and/or free-text fields); however, this detail is not always captured completely (e.g. visit reason may be missing entirely, incomplete or ambiguous). We therefore followed a hierarchical approach to assigning and classifying RFVs, drawing from three key data fields in the EMR. First, we examined the ‘visit reason’ field. If this field was empty or incomplete, we next checked the ‘MBS item’ field, and then the ‘prescription indication’ field to infer clinical activity (see Fig. 2). A single clinical visit could be associated with multiple RFVs. Where insufficient detail was available to establish the reason for a clinical visit (e.g. ‘telephone consult’ or ‘first visit’), we treated RFV as missing.

Assigned RFVs were next classified according to the ICPC-2 (WHO 2005), a standardised system in which primary care encounters can be categorised based on the reasons the patient has come for the consultation, the problems managed during the encounter, and any procedures, referrals, imaging and pathology tests. Under ICPC-2, patient RFVs are classified according to the relevant body system affected (using 17 different ‘chapter’ codes; e.g. code D = digestive), along with the content of the consultation (using a ‘component’ code). These two elements are combined to give a final ICPC-2 classification code (e.g. the ICPC-2 code for appendicitis is D88; WHO 2005). In the present study, ICPC-2 codes were manually mapped to RFV information extracted from the EMR. Where any classification uncertainty arose, decisions were reviewed by a general practitioner (LS) with speciality interest in adolescent health. Final ICPC-2 codes were then used to calculate relative frequency of RFVs per 100 clinical visits.

Within Best Practice EMR, GPs can select patient gender from a drop-down menu of five options: male, female, other, blank and unknown. Patients recorded with other gender (intended to represent non-binary gender identification) represented a very small fraction of visits in our sample, whereas the gender options blank and unknown capture cases where patient gender has not been recorded or is indecipherable on a patient registration form (i.e. missing data). For these reasons, we do not report rates for these gender categories.

Patient age was collapsed into three age bands; early adolescent (ages 10–14 years), mid-adolescent (ages 15–19 years) and late adolescent (ages 20–24 years), based on the patient’s age on 1 January 2019. The geographic location of each visit (locality) was classified using the Modified Monash Model category (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care 2021), with MM1 areas labelled as ‘city’ and all other areas grouped as ‘regional’.

Data analysis

The main indicators of interest in examining adolescent primary care visits were: (1) annual rates of clinical visit per patient (based on data gathered over a single year), and (2) frequencies of different RFVs. These were examined both for the overall cohort of adolescent patients, and by age band, gender and locality. Visit rates are expressed as mean annual visits per patient, whereas frequency of different RFVs are presented by ICPC-2 classifications, and were calculated as the number of RFVs per 100 patient visits. Patient visits for which no RFVs were able to be assigned were not included in the denominator when calculating rates of RFV per 100 visits.

Several cross-chapter groupings of interest were also examined (i.e. higher-order classifications that combined rates across ICPC-2 chapters), including reason visits relating to preventive vaccination and medication (e.g. sexual and reproductive health, vaccines, lifestyle counselling), and several key GP processes (discussion of results, follow-ups, medications and referrals). All analyses were conducted using Stata software (BE ver. 17.0; StataCorp).

Results

Sample characteristics

The final dataset consisted of 22,062 adolescent patients, who recorded a total of 63,706 visits to primary care across the 12-month period, while seeking medical support for 79,490 total RFVs (see Table 1). Adolescent patients were drawn from 29 participating general practice clinics across Victoria; 16 practices were located in a major city and 12 were classified as regional.

| Overall | Age (10–14 years) | Age (15–19 years) | Age 20–24 years | Locality | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Total A | Female | Male | Total A | Female | Male | Total A | City | Regional | |||

| Patients, n (%) | 22,062 (100) | 3046 (13.8) | 3242 (14.7) | 6316 (28.6) | 4223 (19.1) | 3049 (13.8) | 7318 (33.2) | 5150 (23.3) | 3223 (14.6) | 8428 (38.2) | 11,785 (53.4) | 10,277 (46.6) | |

| Visits, n (%) | 63,706 (100) | 8053 (12.6) | 8127 (12.8) | 16,237 (25.5) | 13,752 (21.6) | 7871 (12.4) | 21,728 (34.1) | 17,232 (27.0) | 8400 (13.2) | 25,741 (40.4) | 32,258 (50.6) | 31,448 (49.4) | |

| RFV B, n (%) | 79,490 (100) | 9647 (12.1) | 9450 (11.9) | 19,167 (24.1) | 17,614 (22.2) | 9623 (12.1) | 27,389 (34.5) | 22,264 (28.0) | 10,517 (13.2) | 32,934 (41.4) | – | – | |

| Visits per patient, mean (CI) | 2.89 (2.85–2.93) | 2.64 (2.57–2.72) | 2.51 (2.43–2.58) | 2.57 (2.51–2.63) | 3.26 (3.18–3.33) | 2.58 (2.50–2.66) | 2.97 (2.91–3.03) | 3.35 (3.27–3.42) | 2.61 (2.53–2.68) | 3.05 (2.98–3.12) | 2.74 (2.69–3.00) | 3.06 (2.79–3.11) | |

Data for patients missing on gender (blank, unknown) or classified as ‘other’ are not presented due to very low frequencies.

Patients in the oldest adolescent age bracket (20–24 years) accounted for the greatest proportion of patents (38.2%; 8428/22,062), as well as the greatest proportion of visits (40.4%; 25,741/63,706). By gender, females accounted for 56% of the patient cohort (3046 + 4223 + 5150/22,062) and >60% (8053 + 13,752 + 17,232/63,706) of the general practice visits observed; females aged 20–24 years accounted for the largest proportion of recorded patient visits (27.1%; 17,232/63,706). Patients whose gender was recorded as ‘other’ made up just 0.1% of total patients and attended 0.1% of recorded general practice visits (values not presented in tables due to very low frequencies). In terms of locality, patient numbers and visits were split roughly evenly between city and regional practices.

Rates of visit to general practice

The average rate of visits per patient across the cohort was 2.89 visits per patient (see Table 1). Visit rates were found to increase with increasing age, with females in the 20–24-year-old age band showing the highest average visit rate of 3.35 visits per patient. Within each age category, females visited general practice at slightly higher rates than males, and on average attended approximately 0.5 more general practice visits per year than males. Overall rates of visit to regional practices were slightly higher than those to city practices (3.06 vs 2.74, respectively).

Reasons for visit

Information (either partial or complete) was present in the ‘visit reason’ field of the EMR for a majority (almost 99%) of recorded clinical visits. For 14% of clinical visits (9132/63,708), we could not assign an ICPC-2 code to RFV, because there was insufficient detail in the EMR (across the three fields examined). Table 2 shows overall rates of RFV for each of the 17 ICPC-2 chapters (representing major body systems; presented in descending order of overall frequency) along with the 45 most frequently recorded RFVs per 100 visits (based on ICPC-2 classification) separately for males and females, and for each age band (10–14 years, 15–19 years and 20–24 years).

| ICPC-2 chapter and code | Overall | Age (10–14 years) | Age (15–19 years) | Age (20–24 years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |||

| Respiratory | 20.3 | 26.0 | 28.1 | 17.5 | 24.4 | 15.1 | 19.0 | |

| (20.0–20.7) | (24.9–27.1) | (26.9–29.2) | (16.7–18.2) | (23.3–25.5) | (14.5–15.7) | (18.0–19.9) | ||

| URTI (acute) | 8.4 | 7.9 | 5.8 | 7.5 | 5.5 | 7.2 | ||

| Respiratory preventive vaccination/immunisation | 4.5 | 4.4 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 1.3 | 1.6 | ||

| Asthma | 3.4 | 4.1 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 1.5 | ||

| Tonsillitis acute | 1.5 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 1.5 | 1.6 | ||

| Respiratory other preventive procedures | 1.2 | 1.6 | * | 0.6 | * | * | ||

| Cough | 1.1 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.0 | ||

| Allergic rhinitis | 0.7 | 1.2 | * | 1.1 | * | 0.8 | ||

| Respiratory infection other | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.1 | * | 0.7 | ||

| Sinusitis acute/chronic | 0.8 | * | 0.9 | 0.8 | * | 0.8 | ||

| Throat symptom/complaint | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.8 | ||

| Psychological | 19.6 | 19.0 | 16.1 | 21.6 | 19.5 | 18.5 | 21.6 | |

| (19.2–20.0) | (17.9–20.1) | (15.1–17.2) | (20.8–22.5) | (18.4–20.7) | (17.8–19.2) | (20.6–22.8) | ||

| Anxiety disorder/anxiety state | 4.3 | 2.1 | 7.1 | 4.6 | 5.9 | 6.9 | ||

| Psychological consult with primary care provider | 4.4 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 3.4 | 4.1 | 3.8 | ||

| Psychological symptom/complaint other | 1.7 | 3.9 | * | 1.3 | * | * | ||

| Psychological order NOS | 2.9 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 1.6 | 1.9 | ||

| Depressive disorder | 1.2 | * | 2.9 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 2.2 | ||

| Anorexia nervosa/bulimia | 1.2 | 0.2 | 1.1 | * | * | * | ||

| Sleep disturbance | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | * | 0.8 | 1.0 | ||

| Drug abuse | * | * | * | * | * | 0.9 | ||

| Acute stress reaction | * | * | * | * | * | 0.7 | ||

| Skin | 15.8 | 18.7 | 18.4 | 13.9 | 20.2 | 11.4 | 18.5 | |

| (15.5–16.1) | (17.7–19.7) | (17.4–19.4) | (13.2–14.6) | (19.2–21.3) | (10.8–11.9) | (17.5–19.5) | ||

| Acne | 2.8 | 1.2 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 1.3 | 1.0 | ||

| Skin excise/remove/debride | 2.8 | 3.4 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 2.4 | ||

| Dermatitis/atopic eczema | 2.5 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.9 | ||

| Skin infection other | 1.1 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.4 | * | 1.3 | ||

| Skin medical exam partial | * | * | * | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.4 | ||

| Skin symptom/complaint other | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | ||

| Warts | 1.2 | 1.1 | * | 0.8 | * | 0.6 | ||

| Dermatophytosis | * | * | * | 0.9 | * | 1.2 | ||

| Ingrowing nail | 0.6 | 0.9 | * | 1.2 | * | * | ||

| Skin therapeutic procedure NEC | * | 1.1 | * | * | * | * | ||

| Skin disease other | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| General and unspecified | 12.8 | 11.5 | 13.0 | 12.1 | 14.7 | 12.1 | 14.7 | |

| (12.5–13.1) | (10.8–12.3) | (12.2–13.8) | (11.5–12.7) | (13.8–15.6) | (11.6–12.7) | (13.8–15.5) | ||

| Viral disease NOS | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 1.6 | ||

| Weakness/tiredness | 1.4 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 1.5 | ||

| General administrative procedure | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 2.1 | ||

| General symptom/complaint other | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.4 | ||

| General medical exam complete | * | * | * | 0.7 | * | 1.4 | ||

| General therapeutic procedure NEC | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.0 | ||

| General preventive immunisation/medication | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.2 | ||

| Allergy/allergic reaction | 0.7 | 1.2 | * | * | * | * | ||

| Health maintenance/prevention | * | 1.1 | * | 0.8 | * | 1.1 | ||

| General follow-up encounter unspecified | * | 0.7 | * | * | * | * | ||

| Musculoskeletal | 10.3 | 12.4 | 14.0 | 7.2 | 14.2 | 6.7 | 13.1 | |

| (10.0–10.5) | (11.6–13.2) | (13.1–14.8) | (6.7–7.7) | (13.3–15.1) | (6.3–7.1) | (12.3–14.0) | ||

| Injury musculoskeletal NOS | 4.1 | 5.1 | 1.4 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 3.4 | ||

| Low back symptom/complaint | 0.7 | * | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 2.2 | ||

| Knee symptom/complaint | 0.7 | 0.9 | * | 0.9 | * | * | ||

| Bursitis/tendinitis/synovitis | 0.7 | 0.9 | * | * | * | * | ||

| Fracture: hand/foot bone | * | 0.8 | * | * | * | 0.6 | ||

| Fracture other | * | * | * | 0.7 | * | * | ||

| Pregnancy, childbearing and family planning | 8.8 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 15.4 | 0.1 | 19.1 | 0.2 | |

| (8.6–9.1) | (1.6–2.3) | (0.0–0.0) | (14.7–16.1) | (0.0–0.1) | (18.5–19.8) | (0.1–0.3) | ||

| Contraception oral | 0.6 | * | 5.2 | * | 4.1 | * | ||

| Pregnancy | * | * | 1.6 | * | 4.5 | * | ||

| Contraception advice | * | * | 2.7 | * | 2.4 | * | ||

| Contraception other | * | * | 2.5 | * | 2.3 | * | ||

| Abortion induced | * | * | 0.8 | * | 1.2 | * | ||

| Pregnancy/family planning remove/excise | * | * | * | * | 0.9 | * | ||

| Contraception intrauterine | * | * | * | * | 0.7 | * | ||

| Digestive | 8.7 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 7.6 | 7.5 | 9.0 | 11.2 | |

| (8.4–8.9) | (7.9–9.3) | (7.9–9.3) | (7.1–8.1) | (6.8–8.1) | (8.5–9.5) | (10.4–12.0) | ||

| Abdominal pain/cramping | 2.3 | 1.8 | 1.22 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.0 | ||

| Gastroenteritis presumed viral | 1.0 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 2.1 | ||

| Heartburn | * | * | * | * | * | 0.9 | ||

| Change faeces/bowel motions | * | * | * | * | 0.7 | 0.9 | ||

| Constipation | 0.7 | 0.6 | * | * | * | * | ||

| Female genital | 7.0 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 11.3 | 0.0 | 14.9 | 0.0 | |

| (6.7–7.2) | (3.7–4.7) | (0.0–0.1) | (10.6–11.9) | (0.0–0.1) | (14.2–15.5) | (0.0–0.1) | ||

| Female genital other preventive procedures | * | * | 1.4 | * | 3.1 | * | ||

| Female genital disease other | * | * | 1.1 | * | 2.3 | * | ||

| Menstrual pain | 1.1 | * | 1.7 | * | 0.9 | * | ||

| Genital candidiasis female | * | * | 0.7 | * | 1.0 | * | ||

| Menstruation absent/scanty | * | * | 0.9 | * | 0.8 | * | ||

| Menstrual irregularity | * | * | 0.8 | * | * | * | ||

| Menstruation excessive | 0.6 | * | 0.8 | * | * | * | ||

| Vaginal discharge | * | * | * | * | 0.7 | * | ||

| Neurological | 3.9 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.0 | |

| (3.8–4.1) | (3.0–3.9) | (3.1–3.9) | (3.7–4.5) | (3.6–4.5) | (3.8–4.4) | (3.5–4.5) | ||

| Headache | 1.4 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.5 | ||

| Head injury other | * | 1.2 | * | 0.8 | * | * | ||

| Blood and immune | 3.3 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 4.5 | 2.1 | 4.5 | 1.9 | |

| (3.1–3.5) | (2.3–3.1) | (1.5–2.1) | (4.1–4.9) | (1.8–2.5) | (4.2–4.9) | (1.6–2.3) | ||

| Iron deficiency anaemia | 1.6 | * | 2.8 | * | 2.6 | * | ||

| Blood/immune medication | * | 0.6 | * | 1.0 | * | * | ||

| Ear | 2.9 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 4.1 | 1.9 | 3.4 | |

| (2.8–3.1) | (3.6–4.5) | (3.3–4.3) | (1.9–2.4) | (3.6–4.6) | (1.7–2.1) | (2.9–3.8) | ||

| Acute otitis media/myringitis | 1.7 | 1.9 | * | 1.3 | * | 0.8 | ||

| Excessive ear wax | * | * | * | 0.8 | * | 0.7 | ||

| Endocrine/metabolic and nutritional | 2.3 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 2.7 | 2.8 | |

| (2.1–2.4) | (1.8–2.5) | (0.9–1.4) | (2.2–2.7) | (1.3–1.9) | (2.5–3.0) | (2.4–3.2) | ||

| Vitamin/nutritional deficiency | * | * | * | * | 0.7 | * | ||

| Male genital | 1.8 | 0.0 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 4.1 | 0.0 | 6.9 | |

| (1.7–1.9) | (0.0–0.0) | (2.5–3.3) | (0.0–0.0) | (3.6–4.6) | (0.0–0.0) | (6.3–7.5) | ||

| Male genital excise/remove | * | * | * | 1.1 | * | 3.0 | ||

| Male genital disease other | * | 1.3 | * | * | * | * | ||

| Male genital other preventive procedures | * | * | * | * | * | 0.9 | ||

| Urological | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 2.5 | 0.7 | 2.8 | 1.3 | |

| (1.6–1.8) | (0.7–1.1) | (0.2–0.5) | (2.2–2.8) | (0.5–0.9) | (2.5–3.1) | (1.1–1.6) | ||

| Cystitis/UTI | * | * | 1.7 | * | 2.0 | * | ||

| Eye A | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.4 | |

| (1.0–1.2) | (1.1–1.7) | (1.2–1.8) | (0.7–1.1) | (0.9–1.5) | (0.6–0.9) | (1.1–1.6) | ||

| Cardiovascular A | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.7 | |

| (1.0–1.2) | (0.5–0.9) | (0.5–0.9) | (0.8–1.1) | (0.9–1.5) | (1.1–1.4) | (1.4–2.0) | ||

| Social problems A | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| (0.4–0.5) | (0.7–1.2) | (0.5–0.9) | (0.3–0.5) | (0.2–0.5) | (0.2–0.4) | (0.3–0.6) | ||

*Denotes values below threshold; that is, rates are shown for the top 45 most frequent ICPC-2 codes only within each patient group (gender by age-band).

UTI, urinary tract infection; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection; NOS, not otherwise specified; NEC, not elsewhere classified.

Overall, respiratory RFVs and psychological RFVs were most frequent (at a rate of 20.3 and 19.6 reasons per 100 visits, respectively), followed by skin-related RFVs (15.8), and general and unspecified RFVs (12.8). This same group of RFVs featured in the five most frequent reasons across each of the gender-by-age groups, with two exceptions: pregnancy, childbearing and family planning RFVs were common among 15–19-year-old females (15.4, 3rd highest RFV) and 20–24-year-old females (19.1, highest RFV); and female genital RFVs were common among 20–24-year-old females (14.9, 4th highest RFV). Overall, females were found to present more frequently for genital-related and urological-related RFVs than males across all age groups.

Rates of respiratory, skin and musculoskeletal RFVs were generally higher among males compared with females, with differences tending to increase with age. Conversely, females showed higher rates of psychological RFVs than males in the younger two age bands, with this trend reversing at 20–24 years. Psychological RFVs appeared to peak during mid-adolescence (aged 15–19 years) for females (RFV rate 21.6) and late adolescence (aged 20–24 years) for males (RFV rate 21.6).

Differences in adolescent RFVs were next examined by locality of GP clinic (city vs regional practices). These comparisons were based on higher-order groupings of ICPC-2 chapter (body system) only (see Table 3). Compared with city practices, visits to regional practices demonstrated higher rates of psychological and pregnancy/family planning RFVs. Conversely, city practices showed higher rates of respiratory and skin-related RFVs compared with regional practices. Otherwise, RFV rates for most other ICPC-2 categories were similar between different geographic locations.

| ICPC-2 chapter A | Overall | City | Regional | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory | 20.3 | 23.5 | 16.9 | |

| (20.0–20.7) | (23.0–24.1) | (16.5–17.4) | ||

| Psychological | 19.6 | 16.7 | 22.6 | |

| (19.2–20.0) | (16.2–17.2) | (22.0–23.2) | ||

| Skin | 15.8 | 17.5 | 14.0 | |

| (15.5–16.1) | (17.0–18.0) | (13.6–14.5) | ||

| General and unspecified | 12.8 | 13.5 | 12.0 | |

| (12.5–13.1) | (13.1–14.0) | (11.6–12.4) | ||

| Musculoskeletal | 10.3 | 10.2 | 10.3 | |

| (10.0–10.5) | (9.8–10.6) | (10.0–10.7) | ||

| Pregnancy, childbearing and family planning | 8.8 | 6.6 | 11.1 | |

| (8.6–9.1) | (6.3–6.9) | (10.7–11.6) | ||

| Digestive | 8.7 | 9.6 | 7.8 | |

| (8.4–8.9) | (9.2–9.9) | (7.4–8.1) | ||

| Female genital | 7.0 | 6.9 | 7.1 | |

| (6.7–7.2) | (6.6–7.2) | (6.7–7.4) | ||

| Neurological | 3.9 | 3.8 | 4.0 | |

| (3.8–4.1) | (3.6–4.1) | (3.7–4.2) | ||

| Blood and immune | 3.3 | 3.9 | 2.7 | |

| (3.1–3.5) | (3.6–4.1) | (2.5–2.9) | ||

| Ear | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.8 | |

| (2.8–3.1) | (3.8–3.2) | (2.6–3.1) | ||

| Endocrine/metabolic and nutritional | 2.3 | 2.6 | 1.9 | |

| (2.1–2.4) | (2.4–2.8) | (1.7–2.1) | ||

| Male genital | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.5 | |

| (1.7–1.9) | (2.0–2.3) | (1.3–1.6) | ||

| Urological | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | |

| (1.6–1.8) | (1.5–1.8) | (1.6–1.9) | ||

| Eye | 1.1 | 1.3 | 0.9 | |

| (1.0–1.2) | (1.1–1.4) | 0.8–1.0) | ||

| Cardiovascular | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.2 | |

| (1.0–1.2) | (0.9–1.2) | (1.0–1.3) | ||

| Social problems | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.6 | |

| (0.4–0.5) | (0.3–0.4) | (0.5–0.7) |

Finally, rates of presentation for several broad categories of RFVs that combined findings across ICPC-2 chapters were examined (i.e. cross-chapter categories; see Table 4). These key groupings included RFVs relating to preventative vaccination and medication, and ‘process’ RFVs that represent common clinical activities that span multiple ICPC-2 chapters (viz results, follow-up, medications, referrals). Among these groupings, preventative RFVs were the most common, with 6.3 preventive vaccination/medication RFVs for every 100 visits.

| ICPC-2 cross- chapters | Overall | Age 10–14 years | Age 15–19 years | Age 20–24 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |||

| Preventive vaccination and medication | 6.3 | 9.7 | 9.6 | 5.9 | 7.2 | 3.7 | 4.8 | |

| (6.1–6.5) | (9.0–10.4) | (8.9–10.2) | (5.5–6.3) | (6.6–7.8) | (3.4–4.0) | (4.3–5.3) | ||

| Results | 5.1 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 5.2 | 3.8 | 7.0 | 5.4 | |

| (4.9–5.2) | (3.2–4.0) | (2.7–3.4) | (4.8–5.5) | (3.4–4.2) | (6.6–7.4) | (4.9–5.9) | ||

| Follow-up | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.7 | |

| (3.7–4.0) | (3.4–4.2) | (3.2–4.0) | (3.3–3.9) | (3.5–4.4) | (3.8–4.4) | (3.3–4.1) | ||

| Medications | 3.4 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 4.4 | 3.0 | |

| (3.3–3.6) | (1.7–2.3) | (1.8–2.5) | (3.9–4.5) | (2.9–3.7) | (4.1–4.7) | (2.7–3.4) | ||

| Referrals | 2.7 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 2.4 | 2.3 | |

| (2.6–2.8) | (2.4–3.1) | (2.9–3.7) | (2.1–2.6) | (2.8–3.6) | (2.2–2.7) | (2.0–2.7) | ||

Discussion

This study presents a comprehensive examination of adolescent health presentations in Australian general practice across 2019 based on secondary analysis of clinical EMR data provided by a sample of >20,000 adolescent patients attending urban and rural general practices in the state of Victoria. Findings provide a contemporary update on trends in adolescent health in Australian primary care following the last examination of such data some two decades ago (Booth et al. 2008).

Rates of attendance

Overall, young people’s rates of visit and their patterns of primary care presentations showed noticeable variation by age band, gender and locality. Rates of attendance to primary care were found to be highest among older patients, females and those in regional localities; females aged 20–24 years accounted for the largest proportion of recorded patient visits. The reasons that young people present to general practice were found to vary by age, gender and practice locality. Overall, respiratory RFVs and psychological RFVs were most frequent, followed by skin-related RFVs, and general and unspecified RFVs. Rates of respiratory, skin and musculoskeletal RFVs were generally higher among males compared with females, whereas rates of psychological, genital-related and urological-related RFVs tended to be higher among females.

The overall mean attendance rate of young people in our sample was 2.89 visits/patient per year, comparable to the value of 3.00 observed in Booth et al.’s (2008) Australia-wide study of BEACH data from 1999 to 2005. Given that the National Prescribing Service General Practice Insights Report found a similar value of 3.3 visits per patient among Australian young people in 2017–2018 (NPS MedicineWise 2021), this suggests that the rate of general practice encounters for this group has remained relatively stable over time. Although comparison between these datasets may be complicated by the fact that our data reflect Victorian and not national activity, overall rates of Victorian GP encounters have been shown to closely approximate national rates, allowing for meaningful comparison (NPS MedicineWise 2021). These relatively low rates complement recent trends in national health service use data that show young Australians (aged 15–24 years) remain the group least likely to attend general practice relative to all other adult age bands (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2022–2023), a pattern also noted two decades ago in the BEACH data (Booth et al. 2008). It has been argued that low rates of primary care presentation among young people may simply be due to their relative good health (Booth et al. 2008) and consequent reduced healthcare needs. However, a growing body of research has identified a range of barriers to accessing primary care among young people, including confidentiality concerns, cost, lack of youth-friendly services and lack of service awareness (Booth et al. 2004; Tylee et al. 2007), all of which may impact access rates.

Reasons for visit

Young people presented to general practice most frequently for physical (biomedical) concerns, particularly respiratory, skin and general/unspecified physical complaints. This finding is consistent with existing literature on adolescent primary care presentations both from Australia and overseas that show young people present most commonly for biomedical concerns (Booth et al. 2008; Frese et al. 2011).

A key point of divergence in our findings compared with these studies, however, is the high frequency of psychological (mental health) reasons for encounter (the second most frequent RFV by ICPC-2 chapter in our sample). This marks a notable upward shift since the Booth et al. (2008) examination of encounters in Australian general practice between 1998 and 2004, in which mental health presentations were found to be infrequent among adolescent patients. The apparent increase in youth mental health consults to primary care corresponds with recent Australian trends showing a rapid decline in mental health for 15–24-year-olds across the past decade (Wilkins et al. 2022). It may also be related to the introduction of the Better Access scheme by the Australian government in 2006 (Department of Health 2023), which led to a considerably expanded range of mental health treatment services covered under Medicare and provided by GPs and mental health practitioners. Youth access to mental health support has increased dramatically since the inception of this scheme (Jorm and Kitchener 2021).

Increased frequency in adolescent mental health presentations may also be in part due to plausible reduction in stigma associated with mental illness (a known barrier to help-seeking among young people with mental health problems (Brown et al. (2015)) following well-publicised campaigns by national mental health organisations, and through various initiatives that aim to reduce stigma and discrimination towards people with mental illness, although research evidence of program effectiveness is limited (Morgan et al. 2021).

In light of previous research showing stark discrepancies between adolescent mental health needs and rates of general practice management (Hickie et al. 2007), our findings provide encouraging signs of greater adolescent engagement with general practice for psychological issues, and emphasise the continued need for proficiency among GPs regarding youth mental health.

Demographic factors

Between males and females, the largest differences with respect to RFVs were seen for pregnancy/family planning, genital and urological RFVs, all of which were observed at notably higher rates for females across all age groups. This concentration of urogenital and reproductive issues among female adolescents in general practice has been observed in previous studies of adolescent general practice encounters (Booth et al. 2008), and is a likely contributor to the higher overall attendance rate of females observed in our investigation. Moreover, the initiation of sexual activity common during this period of adolescence (Power et al. 2022) may account for the sharp increase in rates of pregnancy/family planning and genital RFVs observed among females in the 15–19 years age group.

Our study used the Modified Monash Model to classify visits as occurring in either city or regional GP settings, and found the rate of youth visits to rural practices to be slightly higher than that for city practices. This is despite a body of research indicating greater barriers to healthcare access among adolescents in regional and remote settings (Quine et al. 2003; Booth et al. 2004). This finding may be due to the relative lack of alternative services in rural communities, necessitating presentation to general practice in cases where adolescents in cities might seek help from other healthcare providers.

Our findings also indicate that regional general practice visits more frequently involve psychological RFVs compared with metropolitan practices, where physical problems (e.g. respiratory, skin) tend to be more common. Despite the prevalence of mental illness being similar between those living in major cities and those in regional areas (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2020–2022), suicide-related contacts in general practice are known to increase with increasing remoteness from urban areas (Harrison et al. 2013). As such, more frequent presentations relating to suicidal ideation or attempt may contribute to the observed higher rate of psychological RFVs in regional practices compared with urban areas. A more detailed analysis of mental health RFVs is required to determine which complaints are responsible for this difference. Also notable is that RFVs related to pregnancy/family planning were almost twice as frequent among regional practices. This may be due, in part, to relatively higher rates of teen pregnancy in regional, rural and remote areas (Family Planning Australia 2022), as well as increased barriers faced by women accessing specialist sexual and reproductive health services in these areas (Wood et al. 2024), and their greater reliance on GPs to deliver reproductive healthcare services in Australian rural communities (The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners 2018).

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to use electronic medical records to comprehensively describe RFVs of adolescent patients in Australian primary care. The use of a large repository of secondary EMR data allowed us to study a sizeable sample of patients and visits across geographically diverse locations over a full calendar year. Our use of EMR data collected at the point-of-care as part of routine clinical practice meant that results were unaffected by recall bias. The records obtained provide rich data on patient encounters across multiple practices, and allow detailed insights to be gleaned of adolescent presentations in Victoria. Although data incompleteness and quality are known limitations of secondary research using EMRs (Canaway et al. 2019), our study sought to address this concern by following a systematic approach to determine which visits in the dataset were clinical in nature, and by utilising multiple data fields (such as MBS item recorded and script provided) to infer clinical activity where RFV was incomplete or not recorded. However, despite the benefits of our adopted multi-step approach, our RFV identification process may have included inaccuracies, as EMRs are imperfect data repositories and their use may lead to under-reporting of diagnoses (Canaway et al. 2024). Although other EMR fields could plausibly have been added to our approach, the combination of the three fields examined was considered to offer the best balance of accuracy, reliability and efficiency.

Several key limitations are also noteworthy. Although our focus on Victorian GP clinics only may limit the generalisability of findings, previous data suggest that overall rates of Victorian GP encounters closely approximate national rates (NPS MedicineWise 2021). Additionally, our decision to maximise consistency in EMR data structure between clinics by including only those sites using the common software package, Best Practice, resulted in the exclusion of >60 Victorian clinics with available data, representing a further potential limit on the generalisability of findings. Likewise, our reliance on data from clinics enrolled in the Patron program (Manski-Nankervis et al. 2024) may impact generalisability. Finally, our reporting of findings based on patient gender may be incomplete, as experiences of primary care among gender-diverse youth may vary from those identifying as male or female (Strauss et al. 2022). These potential limitations may be addressed in future studies by expanding program participation to practices in other Australian states and territories, incorporating additional software vendors, and seeking broader representation of patients from diverse backgrounds.

Conclusion

The study addresses a significant gap in our understanding of the role of general practice for young people in contemporary Australia, and may assist both healthcare providers and policymakers in identifying areas for improvement in the provision of primary care services to this group. Although physical problems continue to predominate among Australian adolescents’ RFVs to general practice, psychological presentations occur more frequently than estimated in past studies. Furthermore, the profiles of adolescent health presentations vary considerably based on age, gender and practice location, likely reflecting differing healthcare needs and access to care within this group. Finally, this study demonstrates that general practice EMR data, despite its limitations, can be harnessed to provide a meaningful description of primary care activity. Future studies using EMRs to describe adolescent reasons for presentation should ensure that issues relating to missing and incomplete data are adequately addressed (as in the present study), and seek to extend the focus to a national sample to confirm generalisability of the trends observed in this Victorian study.

Data availability

The data that support this study cannot be publicly shared due to ethical or privacy reasons. The data are protected due to their highly sensitive nature. Researchers who wish to use the de-identified data held within the Patron primary care data repository may do so by following an application process through the independent Data for Decisions Data Governance Committee, and by satisfying requirements of an ethics committee registered with the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council. Data were analysed using Stata 16 software; coding is available on request.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the assistance of the University of Melbourne’s Data for Decisions Team for their invaluable assistance in extracting, processing and harmonising the EMR dataset examined in this study. We also acknowledge the participation of GPs and general practice clinics participating in the Patron program from which these EMR data was derived.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2020–2022) National study of mental health and wellbeing. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/mental-health/national-study-mental-health-and-wellbeing/latest-release [cited 5 October 2024]

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2022–2023) Patient experiences. Available at https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-services/patient-experiences/latest-release [cited 10 July 2024]

Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care (2021) Modified Monash Model. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/topics/rural-health-workforce/classifications/mmm

Booth ML, Bernard D, Quine S, Kang M, Usherwood T, Alperstein G, Bennett D (2004) Access to health care among Australian adolescents young people’s perspectives and their sociodemographic distribution. Journal of Adolescent Health 34(1), 97-103.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Booth ML, Knox S, Kang M (2008) Encounters between adolescents and general practice in Australia. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 44(12), 699-705.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Brown A, Rice SM, Rickwood DJ, Parker AG (2015) Systematic review of barriers and facilitators to accessing and engaging with mental health care among at-risk young people. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry 8(1), 3-22.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Canaway R, Boyle DIR, Manski-Nankervis J-AE, Bell J, Hocking JS, Clarke K, Clark M, Gunn JM, Emery JD (2019) Gathering data for decisions: best practice use of primary care electronic records for research. Medical Journal of Australia 210(S6), S12-s16.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Canaway R, Chidgey C, Hallinan CM, Capurro D, Boyle DIR (2024) Undercounting diagnoses in Australian general practice: a data quality study with implications for population health reporting. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 24(1), 155.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Department of Health (2023) Better access initiative. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/better-access-initiative [cited 21 March 2023]

Frese T, Klaussa S, Herrmanna K, Sandholzer H (2011) Children and adolescents as patients in general practice – the reasons for encounter. Journal of Clinical Medicine Research 3(4), 177-182.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Harrison C, Bayram C, Britt H (2013) Suicide-related contacts – experience in general practice. Australian Family Physician 42(9), 605.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hickie IB, Fogarty AS, Davenport TA, Luscombe GM, Burns J (2007) Responding to experiences of young people with common mental health problems attending Australian general practice. Medical Journal of Australia 187(S7), S47-S52.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hiscock H, Neely RJ, Lei S, Freed G (2018) Paediatric mental and physical health presentations to emergency departments, Victoria, 2008–15. Medical Journal of Australia 208(8), 343-348.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Jorm AF, Kitchener BA (2021) Increases in youth mental health services in Australia: have they had an impact on youth population mental health? Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 55(5), 476-484.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Manski-Nankervis J-A, Canaway R, Chidgey C, Emery J, Sanci L, Hocking JS, Davidson S, Swan I, Boyle D (2024) Data resource profile: primary care audit, teaching and research open network (patron). International Journal of Epidemiology 53(1), dyae002.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Morgan AJ, Wright J, Reavley NJ (2021) Review of Australian initiatives to reduce stigma towards people with complex mental illness: what exists and what works? International Journal of Mental Health Systems 15(1), 10.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, Ross DA, Afifi R, Allen NB, Arora M, Azzopardi P, Baldwin W, Bonell C, Kakuma R, Kennedy E, Mahon J, McGovern T, Mokdad AH, Patel V, Petroni S, Reavley N, Taiwo K, Waldfogel J, Wickremarathne D, Barroso C, Bhutta Z, Fatusi AO, Mattoo A, Diers J, Fang J, Ferguson J, Ssewamala F, Viner RM (2016) Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. The Lancet 387(10036), 2423-2478.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, Viner RM, Haller DM, Bose K, Vos T, Ferguson J, Mathers CD (2009) Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. The Lancet 374(9693), 881-892.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Quine S, Bernard D, Booth M, Kang M, Usherwood T, Alperstein G, Bennett D (2003) Health and access issues among Australian adolescents: a rural-urban comparison. Rural and Remote Health 3(3), 245.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, Blakemore S-J, Dick B, Ezeh AC, Patton GC (2012) Adolescence: a foundation for future health. The Lancet 379(9826), 1630-1640.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Strauss P, Winter S, Waters Z, Wright Toussaint D, Watson V, Lin A (2022) Perspectives of trans and gender diverse young people accessing primary care and gender-affirming medical services: findings from trans pathways. International Journal of Transgender Health 23(3), 295-307.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (2018) Maternity care in general practice: position statement. (The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners) Available at https://www.racgp.org.au/FSDEDEV/media/documents/RACGP/Position%20statements/Maternity-care-in-general-practice.pdf

Tylee A, Haller DM, Graham T, Churchill R, Sanci LA (2007) Youth-friendly primary-care services: how are we doing and what more needs to be done? The Lancet 369(9572), 1565-1573.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

University of Melbourne Department of General Practice and Primary Care (2024) Data for decisions and the patron program of research. Available at https://medicine.unimelb.edu.au/research-groups/general-practice-research/data-for-decisions [cited 15 July 2024]

Victoria State Government (2022) Our promise, your future: Victoria’s youth strategy 2022–2027. (Department of Families, Fairness and Housing) Available at https://www.vic.gov.au/victorias-youth-strategy-2022-2027

Western Australian Department of Health (2018) WA youth health policy 2018–2023. (Health Networks, Western Australian Department of Health, Perth) Available at https://www.health.wa.gov.au/~/media/Files/Corporate/general%20documents/Youth-Policy/PDF/Youth-policy.pdf

Wood SM, Alston L, Chapman A, Lenehan J, Versace VL (2024) Barriers and facilitators to women’s access to sexual and reproductive health services in rural Australia: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research 24(1), 1221.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Footnotes

1 Before its termination in 2016, BEACH was the most comprehensive and longest-running investigation into the nature of healthcare encounters in Australian general practice. The BEACH program was a continuous national study of the nature and content of encounters in Australian general practice, in which approximately 1000 randomly selected GPs each recorded details of 100 consecutive encounters with patients of all ages, using structured, paper-based surveys. Data collected from this annual program were used to generate a wide body of research into Australian general practice activity, including studies on disease management, common presentations and prescribing patterns (Britt et al. (2016), General practice activity in Australia 2015–16. General Practice Series no. 40. 2016, Sydney: Sydney University Press).