Carer and staff preferences for characteristics of health services delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children: a best–worst scaling study

Shingisai Chando A B * , Martin Howell C D , Janice Nixon E , Simone Sherriff B , Kym Slater F , Natalie Smith G , Laura Stevenson H , Michelle Dickson B , Allison Jaure A C , Jonathan C. Craig I , Sandra J. Eades J Kirsten Howard D

A B * , Martin Howell C D , Janice Nixon E , Simone Sherriff B , Kym Slater F , Natalie Smith G , Laura Stevenson H , Michelle Dickson B , Allison Jaure A C , Jonathan C. Craig I , Sandra J. Eades J Kirsten Howard D

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

Abstract

Prioritising the characteristics of health services delivery can guide improvements to the quality of care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and their carers. The aim of this study was to estimate the relative importance of 20 health services delivery characteristics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

From May 2022 to November 2023, best–worst scaling surveys were distributed in person and online to carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and staff who work at health services used by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Preference scores (0–1) were calculated using multinomial logit regression models. Interaction terms were added to a regression model to examine preference heterogeneity.

A total of 109 surveys were completed. Most participants identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (81%), and were aged ≥30 years (77%), female (83%) and either worked or used health services at an Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (84%). For the combined sample of carers and staff, the most important attribute was ‘Treatment options are explained, and the carer is involved in decisions about the child’s care’, followed by ‘Clinical staff ask carer about their concerns for their child and respond to them’ and ‘Clinical staff provide carers with the skills to manage their child’s health at home’.

Our study identified that communication characteristics related to shared decision-making and empowerment are considered the most important characteristics of health services delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

Keywords: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, best-worst scaling, child health services delivery, children, health policy, health service preferences, health services, Indigenous health.

Background

Delivering patient-centred care that improves patients’ satisfaction and their long-term engagement with health services requires fulfilling the needs and expectations of service users. Several studies have identified characteristics of primary health services, including those specific to health services delivery, that are important to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia (Gomersall et al. 2017; Harfield et al. 2018). In general, these data reflect what is important when delivering adult health services. Data on characteristics of child health services delivery that are particularly important to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parents or caregivers (hereafter referred to respectfully as carers) are limited.

Evidence about the characteristics of health services delivery that positively impact experiences with health services has informed guidelines for developing health services in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, and are evident in service models used by Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs; Australian Government 2016; Campbell et al. 2018; Elvidge et al. 2020). Progress towards improving health services delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can be largely credited to the work of ACCHOs (Campbell et al. 2018; Pearson et al. 2020). ACCHOs are highly effective community-led health services that adopt a holistic approach to healthcare delivery, and lead in creating spaces for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voices to be heard and privileged in primary health care (Pearson et al. 2020).

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, ACCHOs have contributed to improvements in nutrition and growth, mental health, immunisation, ear health, dental care, and social and emotional wellbeing (Campbell et al. 2018). The success of the ACCHO model can be attributed in part to these organisations’ connection and proximity to communities, and their commitment to promoting self-determination (Campbell et al. 2018). However, the systematic gathering of evidence from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health service users to identify the aspects that contribute to positive experiences and the prioritisation of those elements of service delivery varies across ACCHOs and other primary care services (Larkins et al. 2019). Moreover, adequately resourcing the processes that support the service characteristics important to service users in a primary care setting remains challenging (Coombs 2023).

Although most health services attempt to meet the needs of all their service users, trade-offs are inevitable, because budgets are constrained and funding priorities frequently change (Coombs 2023). For example, a health service considering two projects, one to improve cultural safety in the waiting room and the other to incorporate cultural education into a health promotion program, may rely on the same funding pool for both projects. The service may only have sufficient funding for one initiative, forcing it to choose between the two projects. Mismatches between what service users value and what decision-makers perceive as important can result in missed opportunities to provide the services that matter most to service users.

In a recent qualitative study, carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who utilise health services provided by ACCHOs and staff at those services described the health services delivery characteristics and processes (organisational and interpersonal) that are important to them based on their lived experiences (Chando et al. 2022). Carers also described how different aspects of service delivery influenced their decisions to participate in and engage with health programs (Chando et al. 2022). However, as with similar studies, the data are descriptive, and it is unclear how carers value and prioritise those important aspects. Building on this qualitative study and other previous research, this study aimed to evaluate the relative importance of the organisational and interpersonal characteristics of health services delivery that carers and staff found important. It aimed to contribute to a better understanding of the characteristics that enhance the experience of receiving care at health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. The data can inform targeted quality improvement activities, and facilitate the efficient allocation of limited resources while delivering culturally safe care across ACCHOs and other mainstream child health services.

Methods

Study design

We elicited carer and staff preferences for 20 characteristics of health services identified by carers and staff using an object case best–worst scaling (BWS) survey. The BWS technique uses choice modelling to estimate the relative importance of a set of predetermined attributes (Wittenberg et al. 2016; Hollin et al. 2022). The methodology is underpinned by random utility theory, which asserts that when presented with a set of alternatives, individuals will choose the option that maximises their utility (Louviere et al. 2015).

In an object case BWS survey, participants are presented with best–worst tasks, each containing three or more attributes or characteristics. In each best–worst task, participants are asked to select the most important and least important attribute. The attribute options included in each best–worst task are populated from a larger list of attributes. Unlike other ranking exercises, BWS surveys show participants only a subset of attributes rather than the full list of attributes. The relative preferences across all attributes are determined from the choices made across all the best–worst tasks included in the survey. An example of a best–worst choice task is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Positionality of authors

This work was conducted in partnership with ACCHOs, and under the supervision of senior Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander academics. The lead author is a non-Indigenous academic from a culturally and linguistically diverse background who applied a decolonial framework to the design and development of the research.

Participant recruitment and study setting

Aboriginal Research Officers (AROs) at ACCHOs in New South Wales, Australia, assisted in recruiting carers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and staff aged ≥18 years. The ACCHO model of care is holistic, providing a wide range of health services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples across the lifespan. The carers included parents, kinship carers and grandparents, and were eligible to participate if they had at least one Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child in their care and used a child health service or program either at an ACCHO, the local general practice or community health centre or a mainstream hospital. Staff included individuals aged ≥18 years, employed by a child health service providing care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Staff included those in clinical roles; for example, doctors, nurses and allied health staff, and those in administrative roles; for example, receptionists. Health services included medical, dental and other child health programs or services offered at ACCHOs or mainstream health services.

Carers attending an appointment or program at an ACCHO were approached by an ARO or by SC (a non-Indigenous investigator) and invited to complete the survey. A A$25 Woolworths gift card was provided to carers on submission of the survey. Staff at the ACCHOs were informed of the study and invited to participate by an ARO, either in person or via email. To maximise the sample size, an online version of the survey was distributed to carers and staff through the study’s investigator networks.

Survey design and data collection

The attributes used in the survey were chosen based on findings from two systematic reviews and two qualitative studies (Chando et al. 2021a, 2021b, 2022, 2024). Twenty attributes were identified that describe features considered important by carers and staff in the delivery of healthcare services or programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (see Table S2). A reference group including AROs at ACCHOs and non-Aboriginal researchers working closely with ACCHOs reviewed and approved the list of attributes included in the survey.

We used a partially balanced incomplete block design to create the survey, because it is not feasible to include every combination of attributes in a survey. The design included 40 best–worst tasks, each containing four attributes. The 40 tasks were split into four blocks, each containing 10 best–worst tasks. Each of the 20 attributes appeared eight times, with the position randomised across the 40 tasks. The pairing is partially balanced with an average pairwise frequency of 1.26. Each survey respondent completed one block. The design and blocking were completed using the %MktBIBD SAS macro (see Table S3 for the block design). Participants recruited at the ACCHOs completed paper-based surveys, and the AROs distributed them randomly across the blocks while ensuring the blocks were equally distributed across participants. The participants who completed the online versions of the survey were randomly assigned to one block by the software program. The experimental design aimed to balance the attributes across the blocks. On average, the respondents saw each attribute at least twice within each block.

Demographic data were also collected to characterise the participants and enable an analysis of preference heterogeneity related to the demographic characteristics of the respondents. The survey included a free-text question for the participants to provide additional information, including descriptions of characteristics that they felt should have been included. The survey was piloted with a reference group prior to distribution to check for understanding, respondent burden and wording. Feedback from the pilot was used to update the wording in the survey. We used Qualtrics XM for the online survey (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Due to delays from COVID-19 lockdowns, the data collection commenced in May 2022 and was completed in November 2023.

Statistical analysis

A multinomial logit regression model (MNL) was used to estimate the relative preferences, obtained as beta coefficients. Given the sample size, and assumption that participant preferences would be relatively similar, the MNL model was selected to analyse the data. The attribute ‘reception staff and clinical staff are all Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander’ was used as the reference attribute in the MNL and assigned a value of 0. The attributes were dummy-coded with values of 0 if absent, 1 if chosen as the most important (best) and −1 if chosen as the least important (worst).

Because all the beta coefficients generated were on the same scale, they were re-scaled to a range from 0 to 1 for ease of interpretation. We assumed that the participants made their selections sequentially, choosing the most important option first and then selecting the least important option from the remaining three options. As a secondary analysis, we estimated preference heterogeneity in the MNL with participant categories (carers or staff) included as interaction terms. The analysis was undertaken using NLogit ver. 5.0 (Econometric Software, Plainview, NY). The DIRECT checklist was used to report the findings for this study (Ride et al. 2024).

Results

Of the 132 people who started the survey (37 online and 95 using the paper survey), 109 (82.6%) fully completed the survey. Of the participants who commenced the survey online, 24 (64.9%) completed it. For the paper-based survey, five surveys (5%) had missing values, and five (5%) were completed incorrectly (more than one most or least important option selected, or only the most important option selected). Only data from fully completed surveys were included in the choice analyses, because the incomplete surveys had a substantial amount of missing data. Of the incomplete online surveys, only two attempted one best–worst task in the survey, and the rest did not continue with the survey past the demographic questions.

Staff accounted for 54% of participants (n = 59). Of all respondents, 93% either used or worked in health services based in New South Wales. Health services from other states reported included Queensland, Victoria and South Australia. There were more respondents in the 30–50 years age group compared with other age groups: 30 (60%) for carers and 27 (45%) for staff. A greater proportion of staff participants (28%) were aged <30 years compared with carers (16%). Most participants were women, 38 (76%) for carers and 52 (88%) for staff. All carers identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, and of the staff, 38 (64%) identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. Most carers (36; 72%) used an ACCHO in a non-remote area as the primary health service provider for their child, and 55 staff respondents (93%) worked at an ACCHO. Most carers (35; 70%) had more than one child, and the majority of children (94% of responses) were aged >12 months old. Thirty-two staff (54%) were in administrative roles (e.g. receptionists and transport), and 27 (46%) were clinical staff, including doctors, nurses or health workers. Table 1 provides a summary of the participants’ characteristics.

| Characteristic | Carer | Staff | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Respondent | 50 (46) | 59 (54) | 109 (100) | |

| Age group (years) | ||||

| <30 | 8 (16) | 17 (28) | 25 (23) | |

| 30–50 | 30 (60) | 27 (45) | 57 (54) | |

| >50 | 9 (18) | 16 (27) | 24 (23) | |

| No data | 3 (6) | 0 | 3 (6) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 38 (76) | 52 (88) | 90 (83) | |

| Male | 12 (24) | 7 (12) | 19 (17) | |

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status | ||||

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander | 50 (100) | 38 (64) | 88 (81) | |

| Not Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander | 0 | 21 (36) | 21 (19) | |

| Service location | ||||

| ACCHOsA | 36 (72) | 55 (93) | 91 (84) | |

| OtherB | 14 (28) | 4 (7) | 18 (16) | |

| No. of children per carer | ||||

| 1 child | 15 (30) | – | ||

| ≥2 children | 35 (70) | – | ||

| Age range of carer’s children | ||||

| 0–12 months | 5 (6) | – | ||

| 1–5 years | 20 (26) | – | ||

| 6–11 years | 26 (34) | – | ||

| 12–18 years | 26 (34) | – | ||

| Staff role | ||||

| Clinical | – | 27 (46) | ||

| Administrative | – | 32 (54) | ||

Preference scores

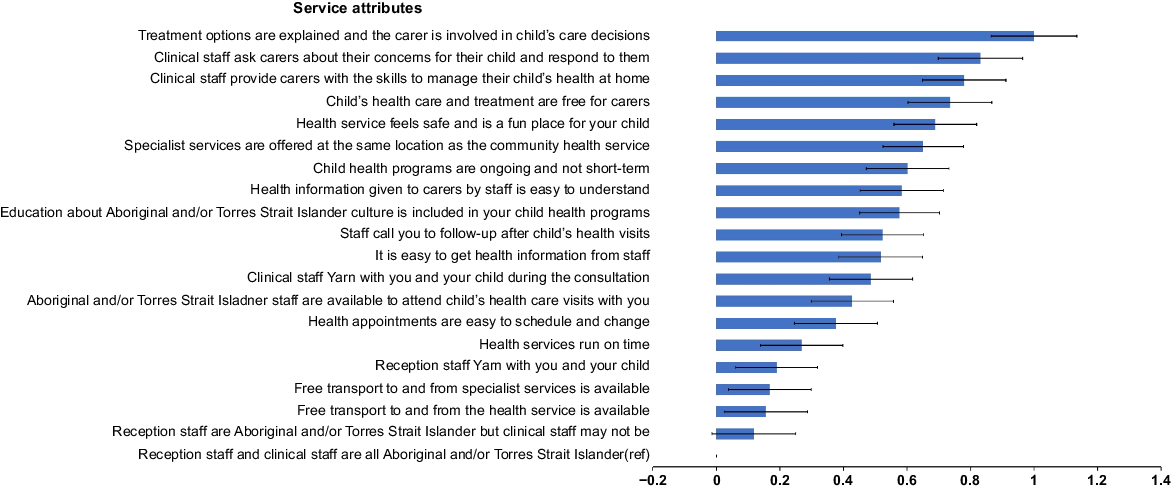

The attribute coefficients were estimated relative to the reference attribute (‘reception staff and clinical staff are all Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander’), and scaled to produce preference scores across a range of 0 for the least important to 1 for the most important (see Table 2). The outcomes are shown in Fig. 1. In the combined sample of carers and staff, the most important attribute, relative to the reference attribute, was ‘Treatment options are explained, and the carer is involved in decisions about the child’s care’, with a preference score of 1 (95% CI 0.87–1.13). The least important attribute was the reference attribute, ‘Reception staff and clinical staff were all Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander’, with an assigned value of 0.

| Attribute | β A | s.e. | 95% CI | Preference score B | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment options are explained and the carer is involved in decisions about child’s care | 2.64 | 0.18 | (2.28, 2.99) | 1 | (0.87, 1.13) | |

| Clinical staff ask carer about their concerns for their child and respond to them | 2.19 | 0.18 | (1.84, 2.54) | 0.83 | (0.70, 0.96) | |

| Clinical staff provide carers with the skills to manage their child’s health at home | 2.06 | 0.18 | (1.71, 2.40) | 0.78 | (0.65, 0.91) | |

| Child’s health care and treatment are free for carers | 1.94 | 0.18 | (1.59, 2.29) | 0.74 | (0.60, 0.87) | |

| Health service feels safe and is a fun place for the child | 1.82 | 0.18 | (1.48, 2.16) | 0.69 | (0.56, 0.82) | |

| Specialist services are offered at the same location as the community health service | 1.72 | 0.17 | (1.38, 2.05) | 0.65 | (0.52, 0.78) | |

| Child health programs are ongoing and not short term | 1.59 | 0.18 | (1.24, 1.93) | 0.60 | (0.47, 0.73) | |

| Health information given to carers by staff is easy to understand | 1.54 | 0.18 | (1.19, 1.88) | 0.58 | (0.45, 0.71) | |

| Education about Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander culture is included in child health programs | 1.52 | 0.17 | (1.19, 1.85) | 0.58 | (0.45, 0.70) | |

| Staff call carers to follow up after child’s health visits | 1.38 | 0.17 | (1.04, 1.72) | 0.52 | (0.39, 0.65) | |

| It is easy to get health information from staff | 1.36 | 0.18 | (1.02, 1.71) | 0.52 | (0.39, 0.65) | |

| Clinical staff yarn with carers and their child during consultations | 1.28 | 0.18 | (0.94, 1.63) | 0.49 | (0.36, 0.62) | |

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander staff are available to attend child’s healthcare visits with carers | 1.13 | 0.17 | (0.79, 1.47) | 0.43 | (0.30, 0.56) | |

| Health appointments are easy to schedule and change | 0.99 | 0.18 | (0.65, 1.34) | 0.38 | (0.25, 0.51) | |

| Health services run on time | 0.71 | 0.18 | (0.36, 1.05) | 0.27 | (0.14, 0.40) | |

| Reception staff yarn with carers and their child | 0.50 | 0.17 | (0.16, 0.84) | 0.19 | (0.06, 0.32) | |

| Free transport to and from specialist services is available | 0.44 | 0.18 | (0.10, 0.79) | 0.17 | (0.04, 0.30) | |

| Free transport to and from the health service is available | 0.41 | 0.18 | (0.06, 0.76) | 0.16 | (0.02, 0.29) | |

| Reception staff are Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, but clinical staff may not be | 0.31 | 0.18 | (−0.04, 0.66) | 0.12 | (−0.01, 0.25) | |

| Reception staff and clinical staff are all Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander (reference) | 0 | 0 |

Combined carer and staff preferences for health services designed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (n = 109).

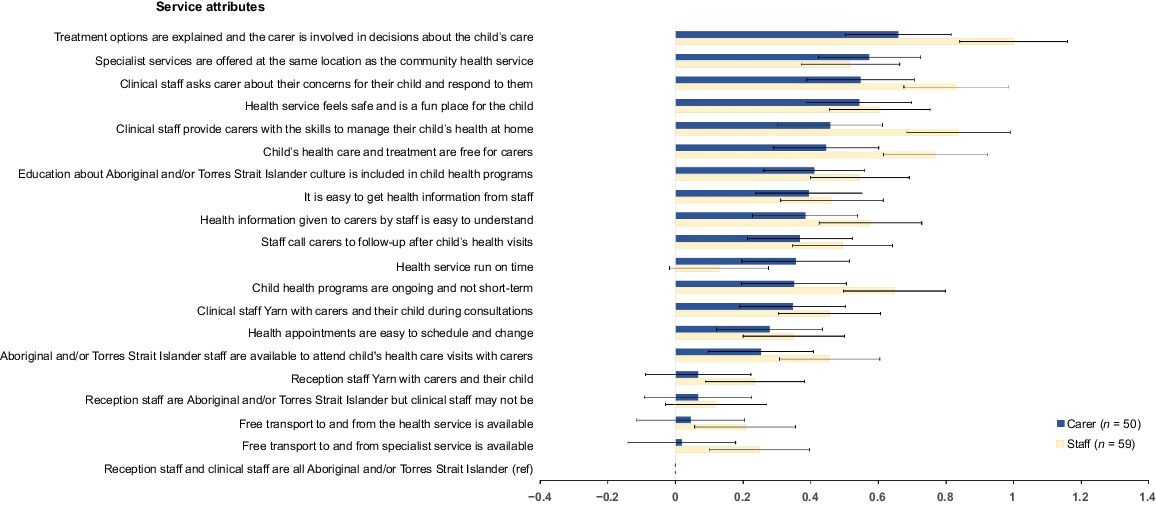

We estimated attribute coefficients to ascertain preference heterogeneity using an MNL model with respondent categories (carers and staff) included as interaction terms. The coefficients were scaled to produce preference scores in the range of 0 for least important and 1 for most important. For both carers and staff, the most important attribute relative to the reference attribute was ‘Treatment options are explained, and the carer is involved in decisions about the child’s care’, with a preference score of 1 (95% CI 0.84–1.16) for staff and a preference score of 0.66 (95% CI 0.50–0.81) for carers. The reference attribute ‘Reception staff and clinical staff are all Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander’ was the least important for both carers and staff. The preference scores for carers and staff are shown in Fig. 2 for a participant-specific comparison.

Participant-specific preferences for health services designed for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children (n = 109).

In addition to the most important attribute, two other attributes in the top five most important attributes were similar for both carers and staff. The attribute ‘clinical staff ask carer about their concerns for their child and respond to them’ was ranked third by both carers (preference score of 0.55, 95% CI 0.39–0.70) and staff (preference score of 0.83, 95% CI 0.68–0.98). Carers ranked the attribute ‘clinical staff provide carers with the skills to manage their child’s health at home’ as fifth in relative importance, with a preference score of 0.46 (95% CI 0.30–0.61). Whereas staff ranked the same attribute as second in relative importance, with a preference score of 0.84 (95% CI 0.68–0.99).

Two attributes in the top five for carers were different to those of staff. Carers chose having specialist services at the same location as the community health service as the second most important attribute, with a preference score of 0.57 (95% CI 0.42–0.72), whereas staff ranked the same attribute as the ninth most important (preference score 0.52; 95% CI 0.37–0.66). Having a health service that felt safe and fun for their child was the fourth most important attribute for carers, with a preference score of 0.54 (95% CI 0.39–0.70), whereas staff ranked the same attribute as the sixth most important (preference score 0.60; 95% CI 0.45–0.75).

Staff chose having the child’s health care and treatment being free for carers as the fourth most important attribute (preference score 0.77; 95% CI 0.61–0.92), and having child health programs that are ongoing and not short term as fifth (preference score 0.65; 95% CI 0.50–0.80). Carers ranked having free care and treatment as the sixth most important attribute (preference score 0.44; 95% CI 0.29–0.60), and having programs that are ongoing and not short term as the 12th most important attribute (preference score 0.35; 95% CI 0.20–0.51).

For staff and carers, the five attributes at the bottom end of the scale were similar. In the bottom five were attributes relating to free transport and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status of the reception and clinical staff. A notable difference in the bottom five was having services run on time. Carers ranked that attribute as the 11th most important (preference score 0.36; 95% CI 0.20–0.52), whereas staff ranked it as the 18th most important attribute (preference score 0.13; 95% CI −0.02 to 0.28). Scaled preference scores are given in Table 3, together with the rankings. Unadjusted beta values and standard errors are provided in Table S4.

| Attribute | Carer (n = 50) | Staff (n = 59) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preference score A | 95% CI | Rank | Preference score A | 95% CI | Rank | ||

| Treatment options are explained and the carer is involved in decisions about the child’s care | 0.66 | (0.50, 0.81) | 1 | 1 | (0.84, 1.16) | 1 | |

| Specialist services are offered at the same location as the community health service | 0.57 | (0.42, 0.72) | 2 | 0.52 | (0.37, 0.66) | 9 | |

| Clinical staff ask carer about their concerns for their child and respond to them | 0.55 | (0.39, 0.70) | 3 | 0.83 | (0.68, 0.98) | 3 | |

| Health service feels safe and is a fun place for the child | 0.54 | (0.39, 0.70) | 4 | 0.60 | (0.45, 0.75) | 6 | |

| Clinical staff provide carers with the skills to manage their child’s health at home | 0.46 | (0.30, 0.61) | 5 | 0.84 | (0.68, 0.99) | 2 | |

| Child’s health care and treatment are free for carers | 0.44 | (0.29, 0.60) | 6 | 0.77 | (0.61, 0.92) | 4 | |

| Education about Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander culture is included in child health programs | 0.41 | (0.26, 0.56) | 7 | 0.55 | (0.40, 0.69) | 8 | |

| It is easy to get health information from staff | 0.39 | (0.24, 0.55) | 8 | 0.46 | (0.31, 0.61) | 11 | |

| Health information given to carers by staff is easy to understand | 0.38 | (0.23, 0.54) | 9 | 0.58 | (0.42, 0.73) | 7 | |

| Staff call carers to follow up after child’s health visits | 0.37 | (0.21, 0.52) | 10 | 0.49 | (0.35, 0.64) | 10 | |

| Health services run on time | 0.36 | (0.20, 0.52) | 11 | 0.13 | (−0.02, 0.28) | 18 | |

| Child health programs are ongoing and not short term | 0.35 | (0.20, 0.51) | 12 | 0.65 | (0.50, 0.80) | 5 | |

| Clinical staff yarn with carers and their child during consultations | 0.35 | (0.19, 0.50) | 13 | 0.45 | (0.30, 0.61) | 13 | |

| Health appointments are easy to schedule and change | 0.28 | (0.12, 0.43) | 14 | 0.35 | (0.20, 0.50) | 14 | |

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander staff are available to attend child’s healthcare visits with carers | 0.25 | (0.10, 0.41) | 15 | 0.46 | (0.31, 60) | 12 | |

| Reception staff yarn with carers and their child | 0.07 | (−0.09, 0.22) | 16 | 0.23 | (0.09, 0.38) | 16 | |

| Reception staff are Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander, but clinical staff may not be | 0.07 | (−0.92, 0.23) | 17 | 0.12 | (−0.03, 0.27) | 19 | |

| Free transport to and from the health service is available | 0.04 | (−0.11, 0.20) | 18 | 0.21 | (0.06, 0.36) | 17 | |

| Free transport to and from specialist services is available | 0.02 | (−0.14, 0.18) | 19 | 0.25 | (0.10, 040) | 15 | |

| Reception staff and clinical staff are all Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander (reference) | 0 | (0, 0) | 20 | 0 | (0, 0) | 20 | |

Results from qualitative data

Thirty-nine respondents (36%) completed the free-text section of the survey and offered additional feedback about what was important to them. Twenty-eight (72%) of those respondents were carers. The themes from the qualitative data included shorter wait times for GP consultations, particularly for priority patients and those with disabilities; options for priority or emergency consultations; the onsite availability of specialist and allied health services, such as pathology, X-rays and ultrasound; navigating the health system, physical and cultural safety; welcoming attitudes from reception staff; having more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff; and access to transport.

Discussion

In this study, carers and staff stated their preferences for health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in terms of 20 attributes that included organisational processes and characteristics, and the interpersonal skills of health professionals. Overwhelmingly, carers and staff reported the importance of having treatment options explained and of shared decision-making regarding the child’s treatment plans. The five most important attributes for both carers and staff were largely communication related, and reflected practices of active listening, responsiveness and empowerment in the delivery of health care for children. To our knowledge, this is the first study to use an object case BWS method to rank characteristics of health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in Australia.

Traditionally, healthcare environments have disempowered Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia, often excluding carers from decision-making affecting their child’s care (Sherwood 2013). The importance of involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carers in their child’s care is well documented (Chando et al. 2020). ACCHOs have led the way in creating spaces in which carers can exercise self-determination in their children’s health care (Harfield et al. 2018; Pearson et al. 2020). Our study confirms that an important aspect of health services delivery for carers is involvement in the decisions affecting their child’s care – specifically, being afforded the opportunity and space to voice their concerns, and being empowered to participate in the process of caring for their child.

The desire for safe and welcoming environments matches guidelines for the provision of health services for children (Australian Government 2016). The qualitative data highlighted the need to have security available when needed, and for community health services to ensure that they have policies and procedures in place to quickly triage people who require urgent mental health support, particularly if children use the same waiting rooms. Cultural safety was another aspect of safety reported as important in this study, and this is consistent with other findings (Gomersall et al. 2017). Included in the safety attribute was having spaces that are fun for the child. Further research is needed to determine whether carers prioritised safety and fun differently, and to ascertain how carers determine a fun space for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Such information would help guide quality improvement efforts to meet service users’ expectations.

Both carers and staff recognised the importance of having free access to health care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. However, given that the proportion of GPs offering bulk-billing or ‘no fee’ services are highest in metropolitan areas compared with regional and large rural towns, for some carers access to ‘free’ health care is limited (O’Sullivan et al. 2022). Policies introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic further affected billing practices (O’Sullivan et al. 2022), limiting options for carers seeking primary care without a co-payment (Graham et al. 2023). Primary care services at ACCHOs are mostly offered without a co-payment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Our findings suggest that carers and staff value health care without out-of-pocket costs, which perhaps reflects an awareness of the limited bulk-billing options outside ACCHOs, and highlights public perceptions of the importance of affordable care (Ellis et al. 2024).

There were differences between staff and carer assessments of the most important attributes. Some attributes were scored higher by carers than staff, such as specialist services being offered onsite and health services running on time. Carers’ preferences for having specialist services at the same location as the community health service underscores the importance of convenient access to specialist services. The importance of onsite access to specialist services is known, and supports the holistic model of health care that ACCHOs promote and service users value (Harfield et al. 2018). Similarly, frameworks for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child health encourage the adoption of integrated service models (Australian Government 2016). Our study suggests that from the carer’s perspective, individual ACCHOs should continue to seek pathways to provide specialist services onsite. Where onsite specialist services are difficult to secure, the feasibility and acceptability of other options, such as telehealth at the ACCHOs, could be explored.

The mismatch in preferences regarding having health services run on time requires further investigation. Our findings suggest that carers value short wait times. The qualitative data revealed differences in needs between carers, with carers whose children have disabilities expressing specific concerns about their options for accessing clinical consultations. These findings suggest a need to recognise the heterogeneity of carer needs when designing health services delivery, carefully considering a range of options for accessing care to suit patients’ needs. Health services should consult with carers about approaches to managing wait times that would be useful to them to the extent that the service has the capacity to make any changes in that area.

The BWS technique offers important benefits in prioritising health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Previous research has used BWS surveys or other choice techniques, such as discrete choice experiments, to value aspects of health services that affect experiences and engagement with the services (Wittenberg et al. 2016; Lungu et al. 2018). The BWS method had advantages over other rating and ranking exercises (Hollin et al. 2022), in that the design of the survey is less cognitively burdensome (Mühlbacher et al. 2016), and most of the respondents in our study completed the exercises independently and with ease.

The BWS object case survey also offered an accessible way to understand the elements of health services delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children that are most important to carers. We adjusted our approaches to administering the survey to accommodate methods that were acceptable to and convenient for the participants. The estimates produced from analysing BWS data are on a single scale, so the results can be ordered and the strength of importance of the attributes examined (Louviere et al. 2015). The results from a BWS study can be easily transferred by service providers into actions to improve service users’ experiences with health services.

There were limitations to the study. The BWS technique is restricted to the attributes included in the tasks; staff and carers could only choose from pre-selected survey attributes. However, we used a variety of best-practice methods, such as literature reviews and qualitative studies capturing data directly from stakeholders, to select the attributes to be included in the survey. We also cross-checked the draft attributes with a reference group to inform the final selection of the attributes. The similarities in the themes from the qualitative section to the included attributes, and participants stating that the attributes were all important reinforced our confidence in the selection.

A limitation to the BWS survey was that some attributes capture more than one issue, which complicates interpretation, as one issue may be more or less important than the other. The attributes were developed such that they closely aligned with the literature around processes that are important and service delivery choices that services grapple with. As such for some attributes, the combination of issues rather than the single item was thought to better capture the service delivery; for example, during a consultation. Further breakdown of attributes also increases the complexity of the BWS survey. The need to address complexity is a limitation of all preference elicitation surveys in that they cannot include all possible attributes.

The participants who completed paper surveys were mostly recruited from ACCHOs in NSW. The study results may not fully represent the preferences of staff and carers who do not attend the participating ACCHOs or any ACCHO. However, the ACCHOs involved in this study are located in regional and urban or metropolitan areas, and the additional data from the online surveys captured a diversity of preferences. Future research could expand the reach of this survey, recruit more staff and carers from mainstream health services and other States and Territories, and compare the findings with the results from this study.

Conclusion

When services that provide health care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children identify what is important to parents and their children, and incorporate these priorities into service design and delivery, they can positively affect engagement, participation and child health outcomes. Our study elicited preferences to inform decisions about priority areas for resourcing and aspects of services that may not have previously been considered among the most important to service users. Our study revealed the importance of communication that values carers as partners, and uses active listening, relevant and appropriate responsiveness, and empowerment. Mainstream health services without close links to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are vulnerable to mismatches in prioritising the most important aspects of health services delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Such services could benefit from using the approach in this paper to enhance their decision-making processes.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of funding

SC was a recipient of a National Health and Medical Research Council Postgraduate Scholarship award, and was supported by SEARCH (The Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health), which was funded by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (1023998, 1035378, 1124822 and 1135271), the NSW Ministry of Health, and the Commonwealth Department of Health. The funders did not have any role in the study design, data collection, analysis and manuscript preparation.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the contributions of all respondents to this project, and the Traditional Custodians of the lands on which this research was conducted and written, and pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging.

References

Campbell MA, Hunt J, Scrimgeour DJ, Davey M, Jones V (2018) Contribution of Aboriginal community-controlled health services to improving Aboriginal health: an evidence review. Australian Health Review 42, 218-226.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Chando S, Craig JC, Burgess L, Sherriff S, Purcell A, Gunasekera H, Banks S, Smith N, Banks E, Woolfenden S (2020) Developmental risk among Aboriginal children living in urban areas in Australia: the Study of Environment on Aboriginal Resilience and Child Health (SEARCH). BMC Pediatrics 20, 13.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chando S, Howell M, Young C, Craig JC, Eades SJ, Dickson M, Howard K (2021a) Outcomes reported in evaluations of programs designed to improve health in Indigenous people. Health Services Research 56, 1114-1125.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chando S, Tong A, Howell M, Dickson M, Craig JC, Delacy J, Eades SJ, Howard K (2021b) Stakeholder perspectives on the implementation and impact of Indigenous health interventions: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Health Expectations 24, 731-743.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chando S, Dickson M, Howell M, Tong A, Craig JC, Slater K, Smith N, Nixon J, Eades SJ, Howard K (2022) Delivering health programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children: carer and staff views on what’s important. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 33, 222-234.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Chando S, Howell M, Dickson M, Jaure A, Craig JC, Eades SJ, Howard K (2024) Factors informing funding of health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children: perspectives of decision-makers. Australian Journal of Primary Health 30, PY24054.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ellis LA, Dammery G, Gillespie J, Ansell J, Wells L, Smith CL, Wijekulasuriya S, Braithwaite J, Zurynski Y (2024) Public perceptions of the Australian health system during COVID-19: findings from a 2021 survey compared to four previous surveys. Health Expectations 27, e14140.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Elvidge E, Paradies Y, Aldrich R, Holder C (2020) Cultural safety in hospitals: validating an empirical measurement tool to capture the Aboriginal patient experience. Australian Health Review 44, 205-211.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Gomersall JS, Gibson O, Dwyer J, O’Donnell K, Stephenson M, Carter D, Canuto K, Munn Z, Aromataris E, Brown A (2017) What Indigenous Australian clients value about primary health care: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 41, 417-423.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Graham B, Kruger E, Tennant M, Shiikha Y (2023) An assessment of the spatial distribution of bulk billing-only GP services in Australia in relation to area-based socio-economic status. Australian Journal of Primary Health 29, 437-444.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Harfield SG, Davy C, Mcarthur A, Munn Z, Brown A, Brown N (2018) Characteristics of Indigenous primary health care service delivery models: a systematic scoping review. Globalization and Health 14, 12.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hollin IL, Paskett J, Schuster ALR, Crossnohere NL, Bridges JFP (2022) Best-worst scaling and the prioritization of objects in health: a systematic review. PharmacoEconomics 40, 883-899.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Larkins S, Carlisle K, Turner N, Taylor J, Copley K, Cooney S, Wright R, Matthews V, Thompson S, Bailie R (2019) ‘At the grass roots level it’s about sitting down and talking’: exploring quality improvement through case studies with high-improving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary healthcare services. BMJ Open 9, e027568.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lungu EA, Guda Obse A, Darker C, Biesma R (2018) What influences where they seek care? Caregivers’ preferences for under-five child healthcare services in urban slums of Malawi: a discrete choice experiment. PLoS ONE 13, e0189940.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mühlbacher AC, Kaczynski A, Zweifel P, Johnson FR (2016) Experimental measurement of preferences in health and healthcare using best-worst scaling: an overview. Health Economics Review 6, 2.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

O’Sullivan BG, Kippen R, Hickson H, Wallace G (2022) Mandatory bulk billing policies may have differential rural effects: an exploration of Australian data. Rural and Remote Health 22, 7138.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Pearson O, Schwartzkopff K, Dawson A, Hagger C, Karagi A, Davy C, Brown A, Braunack-Mayer A, on behalf of the Leadership Group guiding the Centre for Research Excellence in Aboriginal Chronic Disease Knowledge Translation and Exchange (CREATE) (2020) Aboriginal community controlled health organisations address health equity through action on the social determinants of health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. BMC Public Health 20, 1859.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ride J, Goranitis I, Meng Y, LaBond C, Lancsar E (2024) A reporting checklist for discrete choice experiments in health: the DIRECT checklist. PharmacoEconomics 42, 1161-1175.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Sherwood J (2013) Colonisation – it’s bad for your health: the context of Aboriginal health. Contemporary Nurse 46, 28-40.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wittenberg E, Bharel M, Bridges JFP, Ward Z, Weinreb L (2016) Using best-worst scaling to understand patient priorities: a case example of Papanicolaou tests for homeless women. The Annals of Family Medicine 14, 359-364.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |