A qualitative evaluation of the Enough Talk, Time for Action male health and wellbeing program: a primary health care engagement strategy designed with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males

Kootsy Canuto A B , Celina Gaweda B C * , Corey Kennedy B C , Douglas Clinch B , Bryce Brickley A , Oliver Black

B C * , Corey Kennedy B C , Douglas Clinch B , Bryce Brickley A , Oliver Black  D , Rosie Neate B C , Karla J. Canuto A , Cameron Stokes A , Gracie Ah Mat A Kurt Towers E

D , Rosie Neate B C , Karla J. Canuto A , Cameron Stokes A , Gracie Ah Mat A Kurt Towers E

A

B

C

D

E

Abstract

Improving engagement and utilisation of Primary Health Care Services (PHCS) by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males is critical to advancing current physical and mental health outcomes among the subgroup with the highest burden of disease in Australia. PHCS are a first point of contact, coordinating services essential in preventing and managing these conditions. A Men’s Group was established within a South Australian Aboriginal PHCS as a strategy to address documented barriers of access to health care. This study aimed to explore participant experiences and perspectives of the Men’s Group initiative to inform the program.

This Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander led qualitative study used an Aboriginal Participatory Action Research (APAR) framework and a Continuous Quality Improvement approach to gather and transfer Indigenous Knowledges. Semi-structured interviews were conducted by and with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men attending the Men’s Group. Data were analysed using thematic network analysis.

Thirty two participants were interviewed in total. Five global themes were identified: (1) Facilitates and strengthens social and emotional wellbeing (SEWB), (2) Acquiring health knowledge and care is valued, (3) Provide greater opportunities to strengthen connection to culture, (4) Foster individual and collective self-determination, and (5) Improve access and enhance program delivery.

This study demonstrates the effectiveness of APAR to enhance Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male engagement with PHCS through prioritising their voices to co-design a culturally responsive male health program. The findings illustrate profound SEWB, empowerment and health awareness outcomes, resulting from engaging in the newly established, localised Men’s Group.

Keywords: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, Aboriginal participatory action research, engagement strategy, health and wellbeing program, Indigenous, men’s group, men’s health, primary health care.

Introduction

Background

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders advocating for sovereignty in addressing health and wellbeing outcomes has resulted in positive shifts towards decolonising health policy and practice. Ongoing disparities in social determinants of health on Australia’s First Nations Peoples stem from the impacts of colonisation and systemic failures to reduce health inequity (Prehn and Ezzy 2020). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males continue to experience the highest rates of morbidity, mortality, and burden of disease in Australia (Wenitong et al. 2014; Bailie et al. 2017). According to Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet’s most recent overview of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health status, the current Iife expectancy of males is 8.8 years less than non-Indigenous males, and 4322 of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male deaths between 2015 and 2019 were deemed preventable with timely and effective health care (Durbin et al. 2025). The need for greater focus on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male health has been acknowledged (Smith et al. 2008; Canuto et al. 2019), however, there is little applied research aiming to improve access to and utilisation of Primary Health Care Services (PHCS) by them.

PHCS in Australia play a critical role in the early detection and management of diseases, offering annual health checks at no out-of-pocket cost for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Peoples to identify and address chronic disease risk factors. These checks, delivered for adults under item 715 of Australia’s Medicare Benefits Schedule, are typically led by general practitioners (GPs) in PHCS (DoHDA 2025). Between June 2023 and 2024, approximately 25.5% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males had a health check via this initiative (AIHW 2024). This highlights the improvements that could be made to men’s health if new approaches are developed to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males’ access and utilisation of preventative care.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men tend to underutilise PHCS, likely due to complex barriers they face, such as feelings of invincibility or embarrassment, experiences of racial discrimination, disempowerment, and lack of transport, health awareness, or access to male health professionals (Wenitong et al. 2014; Canuto et al. 2018a). A previous study exploring engagement with PHCS in Adelaide, South Australia (SA) and Far North Queensland highlighted enabling factors influencing the utilisation of PHCS by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men, which include feeling culturally safe, dedicated men’s services, and rapport with health service staff (Canuto et al. 2018a). Furthermore, strengthening culture is known to positively restore Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male identities disrupted by colonisation, in-turn improving health and wellbeing (Prehn and Ezzy 2020). This can be achieved by providing culturally appropriate, community-defined, gender-specific initiatives, favourable to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men. This emphasises the importance of genuine collaboration with local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and engaging them to develop grassroots strategies for healthcare planning and delivery.

More broadly, there is opportunity to strengthen the evidence base for monitoring and evaluation in Indigenous male health programs in primary care settings, globally. Although strategies to improve PHCS utilisation by Indigenous men have been implemented in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States, they have lacked rigorous evaluation (Canuto et al. 2018b). In Australia, a recently published scoping review on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male health and wellbeing programs found that only 28 of 54 identified programs reported any evaluation outcomes, with inconsistencies in the quality of outcomes reported (Canuto et al. 2025). Moreover, only four programs explicitly stated they were evaluated by outcome measures determined with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (Canuto et al. 2025). Collaborative evaluation approaches are essential to ensure the future delivery of Indigenous men’s health programs are beneficial and culturally appropriate.

Men’s groups are an effective strategy to improve health and wellbeing outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and can foster important health indicators such as social and emotional wellbeing (SEWB), self-determination, empowerment, and health literacy (Tsey et al. 2002; Cavanagh et al. 2022). Our research project titled ‘Enough Talk, Time for Action’ (ETTA) developed in collaboration with an Aboriginal Primary Health Care Service (APHCS) in SA aimed to improve and increase PHCS engagement and utilisation by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men by providing co-ordinated responses to their SEWB needs. The ETTA research team, led by a Wagadagam man (KC – Mabuiag, Torres Strait), are a collaborative group of multi-disciplinary researchers. This research was conducted by Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islanders (KC, KT, DC, CK, CS, KJC, OB, GAM) and non-Indigenous allies (CG, RN, BB) with extensive experience in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health (broadly and specific to males) with communities and related fields, such as health promotion and program evaluation. Indigenous research capacity building within the project included supporting DC and CK in their roles and tertiary studies and the provision of work experience for three SA based Aboriginal university students through cadetships and internships. Two-way learning was actively encouraged within the team.

A fortnightly Men’s Group was co-designed to facilitate better engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males and was hosted and delivered by the APHCS. The Men’s Group provided male consumers of the APHCS with opportunities to manage and address their health and wellbeing needs and build rapport with staff. This study aimed to explore the experiences and perspectives of the men who participated in the Men’s Group, focusing on the program’s appropriateness, acceptability, and areas for improvement.

Methods

Methodology

The ETTA project engaged an Aboriginal Participatory Action Research (APAR) methodology within an Indigenist Research framework. This decolonising approach centralises Indigenous Knowledges, positioning Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men as leaders and experts to inform the research at every level (Dudgeon et al. 2020). Upholding the principles of self-determination, lead researcher KC engaged in extensive consultation with all APHCSs across SA, building meaningful relationships with local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men, Elders, community leaders and stakeholders to understand the utilisation of PHCSs. This foundational work resulted in identifying community priorities, namely collaborating with community men to guide initiatives for PHCS engagement. This engagement and earlier research identified male-specific initiatives to be a favourable and effective approach.

Positionality

The authors of this paper include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (KC, KT, DC, CK, OB, CS, GAM, KJC) and non-Indigenous (CG, RN, BB) health researchers from both industry (KT) and academia. All non-Indigenous researchers undertook cultural awareness training and understand Indigenous research methodologies.

Design

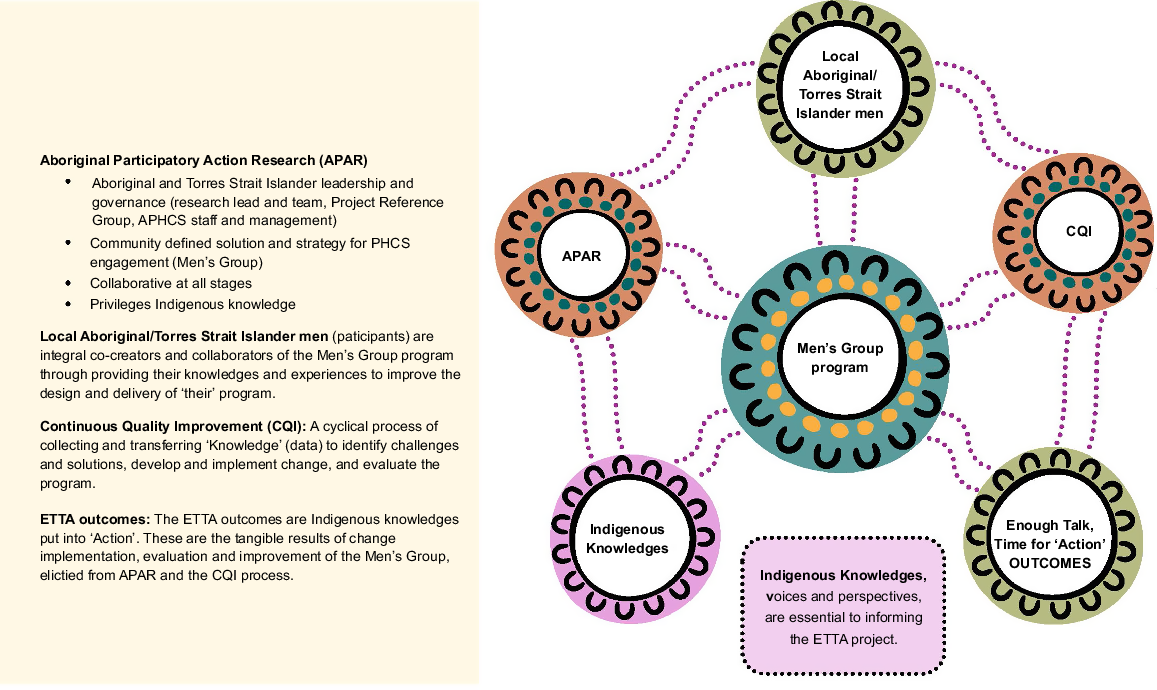

The Men’s Group was an engagement strategy co-designed with senior staff at the APHCS and the Project Reference group, comprising local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men, who provided guidance on project activities, two of whom were Elders. This ensured the project’s conception, research framework, and implementation were culturally informed. To compliment the ETTA project’s APAR methodology, a Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) approach was applied as a structured process to gather and transfer Indigenous Knowledges, through a cyclical process of identifying challenges and solutions, developing and implementing change, and evaluating the quality and delivery of the Men’s Group program (NACCHO 2018). The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander led, cross-cultural research team conducted an exploratory and descriptive qualitative study using semi-structured interviews with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men who attended the program to inform, improve, and assess the quality of the ETTA Men’s Group. The knowledge constructed was fed back to APHCS staff and management and the Project Reference group via reports developed by the research team following each iteration of interviews and analysis. The APHCS implemented viable strategies put forward. This CQI process occurred twice during the project. The reports provided direct evidence for the APHCS to support reform and develop a tailored health and wellbeing program for their network of local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male clients (Canuto et al. 2022; Kennedy et al. 2024). Fig. 1 illustrates how the CQI process functioned. Fig. 2 shows the relationship and interplay between APAR and CQI, with Indigenous Knowledges connecting each aspect of the ETTA project.

Setting

This study was conducted with a state government funded APHCS, in a metropolitan suburb in SA, on the lands of the Kaurna People. The inaugural Men’s Group session was held in October 2021. This service has several clinics within its network. Sessions were mostly held at one clinic and later occasionally rotated to other clinics in response to strategies identified in the first CQI cycle. Sessions were facilitated by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male SEWB officers of the APHCS, ran for 2–3 hours, and included the provision of lunch and transport.

Recruitment

Aboriginal male research assistants, DC and CK, attended most sessions enabling rapport and trust building with participants and were responsible for recruiting Men’s Group attendees and conducting interviews. During sessions, DC and CK invited men to participate by requesting signed consent to contact for future interviews. We aimed to sample the maximum number of participants who identified as an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander male, were aged ≥15 years, and had attended at least one Men’s Group session (14 in 2022, 18 in 2023). Informed consent was obtained using plain language information sheets prior to scheduling interviews. Consistent with the research aims, purposive sampling strategies were used to recruit participants of different ages, experiences, and opinions to maximise validity of the findings (Palinkas et al. 2015). We did not aim for data saturation but sought to recruit the maximum number of eligible participants to capture the widest range of perspectives. Recruitment occurred the same way in both iterations of data collection phases of the two CQI cycles.

Data collection and management

Data were collected via one-on-one (n = 28) and focus group (n = 2) interviews. Interview questions were developed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male researchers and the Project Reference group. Protocols regarding the collection, use, management, and storage of data were developed with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and adhered to by researchers. Most participants agreed for interviews to be audio-recorded, however, three did not, and these interviews were recorded using participant-verified notes. Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and de-identified by CK, RN, and CG to preserve anonymity and checked for accuracy with DC and CK. Participants were asked their preferred interview location, with most taking place at participants’ homes or in public settings (parks/libraries). Following interviews, participants were provided with a A$50 food store voucher and an ETTA T-shirt, as a token of appreciation for their contribution. Interview questions included: ‘What do you like/dislike about the Men’s Group?’; ‘What would you change about the Men’s Group?’, ‘How would you describe the Men’s Group?’; ‘Has attending the Men’s Group changed how you manage and look after your health?’, and ‘Has attending the Men’s Group impacted your health and wellbeing?’.

Data analysis

Data were analysed via collaborative thematic network analysis (Attride-Stirling 2001). First, transcript accuracy was verified by DC and CK. Transcripts were re-read by KC, RN, and CG and imported into NVivo for coding and categorisation. Data were then independently coded by CG and RN in NVivo (Ver 12.0, Lumivero 2022). Next, codes were exported, clustered, and organised under similar themes, revealing patterns. Emerging themes were discussed with all authors, then refined to organising themes. Themes were arranged into networks resulting in the development of global themes and verified by KC. Cross-cultural, reflexive practice occurred throughout analysis, enabling two-way learning and Indigenous research capacity building. Following an iterative process, the analysis continued until researchers were satisfied that participant perspectives were accurately reflected through the final themes.

Ethics and governance

Ethics approval was granted by the Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia’s, Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee (04-20-910) and the South Australian Human Research Ethics Committee (2021/HRE00260). The research followed guidelines outlined by the NHMRC, specifically ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and communities, and The South Australia Aboriginal Health Research Accord. Informed consent was obtained from participants prior to undertaking the research.

Results

A total of 55 Aboriginal/Torres Strait Islander men were invited to participate in the study, and 32 participants were interviewed. The 23 men who did not participate were unresponsive to calls and/or had not returned to the Men’s Group. Interviews typically lasted 30–50 min. Initial interviews occurred between May and June 2022, and the second between September and November 2023. Only 10 participants were interviewed during both CQI cycles. Participants were over 40 years of age, with the majority between 50 and 65 years, except one aged in their early 20’s, and resided in suburbs within the local health network.

Themes

Five global themes were identified: (1) Facilitates and strengthens SEWB, (2) Acquiring health knowledge and care is valued, (3) Provide greater opportunities to strengthen connections to culture, (4) Foster individual and collective self-determination, and (5) Improve access and enhance program delivery. Themes 1 and 2 relate to enabling factors of engagement, and the following three themes highlight strategies and areas for improvement (See Table 1). Overall, engaging in the Men’s Group supported the SEWB needs of participants, in turn strengthening their engagement with the health service. Men were empowered from learning more about health by connecting with clinicians and other men. Suggestions for improvement included offering more diverse opportunities to strengthen connections to culture and Country, promoting self-determination, and increasing accessibility for younger males.

Attending the Men’s Group positively impacted the men’s SEWB in several ways. Social connection and interacting with other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men, described as ‘brothers’, was a key benefit. For many, attending group sessions was one of the few social engagements they had. The occasion provided purpose and something to look forward to.

Food is often used to facilitate engagement and relationship-building within community groups. A shared lunch was central to the Men’s Group and was greatly appreciated. Participants were asked how they would describe the Men’s Group and responses often included the provision of food, ‘Men come down and get a free lunch. We talk about health’ (P33). Eating good ‘tucker’ (food) related to statements describing the Men’s Group as a casual, friendly environment. Receiving food was regarded as an added incentive to encourage new members, along with it being a social occasion.

Gaining new relationships was also appreciated. ‘Yarning’, or informal discussions, were frequently observed. The group was an outlet to talk about life’s problems, in addition to improving mental health. One participant who attended sessions with his support worker explained that ‘using’ the Men’s Group helped him manage and confront an ongoing anxiety:

I use the Men’s Group to help control one of my mental health problems which is good for me because I’m frightened of males, full-on. That’s why I use the Men’s Group. (P20)

Coming together was recognised as important for local men, who are isolated and endure hardship:

Yeah, the group’s good for Nunga [Aboriginal people residing in settled areas of SA] men. A lot of them live alone now and have problems. (P25)

Similarly, peer support and sharing experiences were viewed as essential to supporting the SEWB needs of men in this community, highlighting the significance of having the health and wellbeing program available and accessible for them ‘to come together, talk, and address issues’ (P22).

A dedicated, men’s ‘safe space for speaking’ (P5) was acknowledged as important to discuss health issues in a culturally appropriate way. However, embarrassment or stigma inhibited some men from discussing health challenges, ‘The Group needs to come out more. No shame job to say something’s wrong with you’ (P29).

One participant felt discouraged when men were unwilling to engage in conversations with him about health. Group dynamics were at one point affected by disruptive and inappropriate topics of discussion by some members. Furthermore, older men were viewed as keeping their health problems private, ‘Old fellows don’t want to yarn about their health in front of mob. They feel innate shame’ (P1). However, the diversity of men in the group was also positively acknowledged as stimulating a variety of conversation and relatability.

As sessions progressed, open discussions about health became easier. The opportunity to relate to other men upon hearing similar health circumstances provided a sense of security and connection through shared experience:

I was telling [the men] that I just got it [diabetes] and the guy alongside me pulled out his diabetes book and showed me. I was glad I opened up and shared because [then] I didn’t feel alone. So, it was good to go and listen to other people’s journeys. It took that feeling away. I felt safer. (P22)

The Men’s Group was regarded as a culturally safe environment. Men valued feeling accepted as equals in a setting where their cultural identity is not questioned:

I like hanging out with Aboriginal people in a safe environment without people questioning my identity. I’m whiter than you and I cop it from both sides, from the Aboriginal and the Western world. But I always feel welcome. (P19)

Feelings of acceptance and inclusivity in the collective group of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men supported individual SEWB through fostering a sense of belonging and identity, ‘We’re all treated the same… because it’s hard going to places and not feel judged’ (P5). Nevertheless, this quote echoes experiences of social marginalisation elsewhere.

Occasionally, guest speakers (Elders, researchers, health professionals) attended sessions to give presentations on health-related topics. The men often requested topics they were interested in learning for future sessions, such as diabetes and cancer. Participants appreciated having access to new information. This acquisition of health knowledge meant participants were better informed of general health and specific issues affecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men:

Health issues, whether you’re black or white, are fairly similar but some are more pronounced in Indigenous society. So that’s [knowing more about health issues] helped that recognition. It’s been good in that way. (P34)

These learning opportunities at the Men’s Group encouraged motivation for healthy behaviours and encouraged better self-management of health, such as following through on cancer screenings put forward by guest speakers. New health information was considered empowering by one participant who saw value in growing their own knowledge and sharing it with others:

It’s good having guest speakers, because the more information you get the better it is for you, mind wise, it empowers you. Now I know that [information], and I can tell someone else who didn’t know. (P17)

Attendance of GPs and other health professionals was also a way men could get support for their health needs in a casual, opportunistic way. These occasions were also opportunities to build rapport with the health service staff.

Several participants proposed including cultural activities into the program, indicating a desire to strengthen their connection to culture and suggesting opportunities to practice ‘culture’ are not readily available. One participant wanted to learn about his heritage and proposed a 2-day camp where an Elder could teach men about tradition and culture. Other ideas included going on Country trips or ‘fishing’, with one participant adding it could also be a bonding experience to get to know other men in the group. Making artefacts was also suggested, but it was noted that having access to a shed, tools, and materials would be required:

I would like to see them make some boomerangs, didgeridoos, clap sticks, or something like that but they haven’t really got the space to do it. (P28)

Others were interested in learning the Kaurna language and taking excursions to Aboriginal cultural centres. From a Western biomedical model of health perspective, these suggestions would seem beyond the scope of a health and wellbeing program delivered through a PHCS. However, as reflected here, health and wellbeing from an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander standpoint is also achieved by strengthening protective factors known to promote healing, such as connection to culture and Country.

Restoring dignity in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males is a prevalent topic in the discourse surrounding disempowerment resulting from the impacts of colonisation, such as the loss of cultural identity and ability to fulfil cultural responsibilities. One participant spoke about empowering community men through the Men’s Group by nurturing their pride in identity and exercising self-determination:

We need to empower the urban Aboriginal people down here to take back their power, roles, and responsibilities according to community and Aboriginal lore and culture. I’m hoping that the Men’s Group can start to do this so they can get strong and feel valued. (P22)

The potential of the Men’s Group to better support men feel empowered was proposed through developing a ‘charter’ or a set of principles defining the group’s purpose. This form of group-governance is a way collective self-determination could be achieved through taking ownership of their health and wellbeing. Making the charter publicly visible would further affirm the group’s identity, showing the broader community they are positively engaged in working towards achieving their purpose. Ensuring group facilitators continued giving men collective agency in choosing activities of the group, along with enabling discussion on how these could be implemented, were indicated as important to further enable self-determination. Additionally, recognising and acknowledging achievements of members and/or local heroes in group sessions was also suggested to nurture empowerment.

Participants provided insight on how the Men’s Group could be made accessible to other males in the community by considering promotional strategies, alternating locations, and planning future sessions. Overall, ‘word of mouth’ was regarded as the best strategy to increase engagement. It was also suggested the APHCS increase advertising efforts by displaying posters in local shops. However, promoting the Men’s Group in ways that better conveyed the collective purpose and significance of health and wellbeing for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men was deemed important for building a supportive environment.

Hosting sessions outside the clinic in local community settings was suggested as potentially attracting a wider cohort, including younger men. Examples included situating sessions at sporting clubs to increase awareness of men’s health and indicate the service’s genuine investment in the community. Having a community presence would garner respect by indicating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men do and want to look after their health. Similarly, a more forward-facing approach by the APHCS to promote the men’s health program would be a culturally appropriate way to engage the community:

The service is seen as internal. I’m saying as a Kaurna Elder now to come and sit down in the dirt, in the community. (P22)

The importance of attracting a younger demographic to the Men’s Group was also recognised. This approach would enable older men in the group to serve as mentors:

How do we go about teaching the younger fellas? Get them mixing with the older fellas. Lead by example. (P24)

Better planning and notifying of future sessions by scheduling upcoming topics and events was thought to provide structure and allow men to know what to expect or choose whether to attend. Other participants suggested organising occasional excursions to stifle the boredom men may be experiencing. Having a GP or nurse attend sessions to provide ad hoc support, check-ups, or vaccinations was also proposed to facilitate easier access for men to receive health care without having to book an appointment:

Once a month, they should have a needle day [vaccinations] or something. Put a doctor aside to do that in the group. I think they [the men] would do it there and then. (P6)

Discussion

With the aim of learning the appropriateness and acceptability of the implemented program, our study results reveal what participants value and consider important. Overall, the findings highlight a deep and implicit understanding of SEWB in relation to the program – it’s purpose and potential. Participants described factors that supported positive SEWB experiences of the Men’s Group. Suggestions for program improvement reiterate the significance of delivering culturally responsive health programs and highlight a holistic perspective of health, that would further support SEWB by strengthening cultural identity and empowerment, while complimenting biomedical health outcomes.

The need to foster empowerment by supporting cultural pride and identity was recognised as an important aim of the program, enabling individual and collective self-determination of men’s health and wellbeing. From an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander perspective, health is holistically achieved by including a broader set of circumstances influencing health and wellbeing, beyond the presence of illness (Gee et al. 2014). Practising cultural activities strengthen and maintain continuity of culture and is inextricably linked to the health and wellbeing of an individual and their community by reinforcing cultural identity and belonging. This is pertinent for strengthening Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander masculinity and cultural identities (Prehn and Ezzy 2020). Participants acknowledged that achieving these outcomes was enabled by socialising with other men in the group. Likewise, advice to increase promotional strategies portraying the importance of the program in supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male health were viewed necessary to engage the wider community, particularly younger men, and would signify the men as positive leaders, further affirming empowerment.

The ETTA project did not specifically aim to create an ‘empowerment’ program, but rather to establish a co-designed strategy within the APHCS to strengthen engagement with local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men. However, participants reported feeling empowered through the process of being consulted on their perspectives, needs, and priorities while guiding the Men’s Group. This sense of empowerment stemmed from the implementation of the APAR process, where participants exercised self-determination by holding power in decision-making and developing ‘actionable’ responses to improving the program (Dudgeon et al. 2020). Aligning with wider literature, our results show that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men are eager to improve their health and wellbeing (Bulman and Hayes 2011; Canuto et al. 2019) and have a clear understanding of what facilitates better outcomes for them and their community of men.

Our findings are consistent with studies describing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Men’s Groups as environments that improve SEWB (McCalman et al. 2010), foster empowerment (Tsey et al. 2002), and provide incentive for health improvement (Cavanagh et al. 2022). Dedicated and exclusive spaces are settings where men build relationships and gain trust and confidence in discussing health concerns breaking down the stigma of help-seeking (Canuto et al. 2018a). However, as with any social group, interpersonal dynamics can affect engagement. It is important group leaders facilitate inclusive dialogues that promote cooperative discussion. The men communicated this approach to the APHCS through the CQI process, as a strategy to enhance the group dynamic.

Fostering culturally safe environments in PHCSs and men’s groups has been linked to facilitating engagement and effectively improving health and wellbeing outcomes (Bulman and Hayes 2011; Canuto et al. 2018a). Guest speakers presenting on health topics help normalise talking about health and empower men with knowledge on addressing concerns (Cavanagh et al. 2022). Balancing this with activities that support cultural identity and connection reinforces positive SEWB. A collective sense of wellbeing comes to bear when health solutions are developed with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men (Tsey et al. 2002). The autonomy of shared decision-making to lead solutions concerning them is supported through action research and continuous improvements. Together, these conditions provide a conduit where self-determination of health and wellbeing can be achieved.

This paper demonstrates how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men directly contributed to the planning, delivery, and improvement of the program. Taking this line of action is particularly useful for health promotion and primary care practitioners in establishing local health initiatives for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males to improve health equity among this cohort. Furthermore, the implementation and evaluation of the Men’s Group program using CQI and APAR is a strength-based, decolonising approach to addressing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male health (Dudgeon et al. 2020). Local collaboration is essential to identify needs relevant to the community and deliver nuanced solutions (Canuto et al. 2019). The findings highlight what can be achieved by positioning Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men as knowledge holders and active contributors to determine outcomes important to them.

Strengths and limitations

This study responds to calls for more holistic, culturally responsive, and tailored approaches to improve the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males by collaborating with them. Strong Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male leadership, sustained partnerships with the APHCS, and engagement with the project’s focus population and Project Reference group, ensured community identified priorities were addressed in a culturally appropriate and meaningful way. This leadership, along with two-way learning, allowed non-Indigenous researchers to explore Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture and worldviews, while providing opportunities for self-reflection on their worldviews and positionality as researchers. Transparency in knowledge production and shared decision-making was maintained through trusted relationship between all parties.

Initial stages of this project coincided with COVID-19 restrictions, delaying the implementation of the program, only allowing for two data collection phases within the iterative CQI process rather than four, as originally planned. Although this did not impact the quality of the research, longer engagement could have provided further insight for program improvement. A decline in Men’s Group attendance early in 2022, through to June 2023, may have impacted the number of participants interviewed. Furthermore, 23 participants did not respond to recruitment calls in 2022, potentially resulting in more positive perspectives reflected in the findings. However, attendance improved from July 2023, likely resulting from increased promotional efforts by the APHCS, responding to strategies identified from the first CQI cycle. Lastly, the descriptive findings are grounded in a specific social and cultural context, relevant to participants residing in a metropolitan area in SA, accessing a public APHCS. Therefore, the findings may not reflect broader Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men’s perspectives and experiences, or translate distinct priorities of men in other regions or remote settings.

Conclusion

The findings revealed positive accounts on the appropriateness and acceptability of the Men’s Group and, more importantly, strategies to further improve the quality of the program. This knowledge culminated in the evaluation of the health and wellbeing program delivered by the APHCS, using APAR and CQI methods, ultimately leading to valuable outcomes for the men engaging with the program. Participant narratives illustrate the profound SEWB and empowerment outcomes that can be achieved from engaging with culturally responsive health programs, particularly when men are actively involved in the design and delivery of healthcare initiatives aimed to address their needs. The Men’s Group program delivery model in this study showed potential to meet service and community needs and should be adapted for use in other primary care settings through meaningful stakeholder engagement.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data upon request to the Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee at research@ahcsa.org.au. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions imposed by the Aboriginal Health Research Ethics Committee, as they contain information that could compromise the privacy of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander research participants.

Declaration of funding

Funding was received from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC Investigator Grant: APP1175214).

Author contributions

KC and KT conceptualised the project together with the Project Reference Group after KC and DC engaged with community and stakeholders. DC and CK conducted interviews. All authors contributed to stages of data analysis. KC, CG, OB, and CK composed the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically revised the draft, contributed to writing the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Kaurna People, their ancestors and descendants – on whose lands the project was conducted. We also acknowledge the Project Reference Group, our project partners – the management and staff at the APHCS, and participants for their support, dedication, and contribution to the project.

References

AIHW (2024) Health checks and follow-ups for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-australians/indigenous-health-checks-follow-ups [accessed 9 March 2024]

Attride-Stirling J (2001) Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research 1(3), 385-405.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bailie J, Matthews V, Laycock A, Schultz R, Burgess CP, Peiris D, Larkins S, Bailie R (2017) Improving preventive health care in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary care settings. Globalization and Health 13, 48.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bulman J, Hayes R (2011) Mibbinbah and spirit healing: fostering safe, friendly spaces for indigenous males in Australia. International Journal of Men’s Health 10(1), 6-25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Canuto K, Wittert G, Harfield S, Brown A (2018a) “I feel more comfortable speaking to a male”: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men’s discourse on utilizing primary health care services. International Journal for Equity in Health 17, 185.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Canuto K, Brown A, Wittert G, Harfield S (2018b) Understanding the utilization of primary health care services by Indigenous men: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 18(1), 1198.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Canuto K, Harfield S, Wittert G, Brown A (2019) Listen, understand, collaborate: developing innovative strategies to improve health service utilisation by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 43(4), 307-309.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Canuto K, Gaweda C, Brickley B, Neate R, Hammond C, Newcombe L, Gee G, Black O, Clinch D, Smith JA, Canuto KJ (2025) Investigating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male health and wellbeing programs and their key elements: a scoping review. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 36(1), e940.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cavanagh J, Pariona-Cabrera P, Bartram T (2022) Culturally appropriate health solutions: Aboriginal men ‘thriving’ through activities in Men’s Sheds/groups. Health Promotion International 37(3), daac066.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

DoHDA (2025) Medicare benefits schedule – item 715, Item 715. Medicare Benefits Schedule, Australian Government. Available at https://www9.health.gov.au/mbs/fullDisplay.cfm?type=item&q=715 [accessed 28 July 2025]

Gee G, Dudgeon P, Schultz C, Hart A, Kelly K (2014) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing. In ‘Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice’. 2nd edn. (Eds P Dudgeon, H Milroy, R Walker) pp. 55–68. (Kulunga Research Network: West Perth, WA)

McCalman J, Tsey K, Wenitong M, Wilson A, McEwan A, James YC, Whiteside M (2010) Indigenous men’s support groups and social and emotional wellbeing: a meta-synthesis of the evidence. Australian Journal of Primary Health 16(2), 159-166.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K (2015) Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 42(5), 533-544.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Prehn J, Ezzy D (2020) Decolonising the health and well-being of Aboriginal men in Australia. Journal of Sociology 56(2), 151-166.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Smith JA, Braunack-Mayer A, Wittert G, Warin M (2008) “It’s sort of like being a detective”: understanding how Australian men self-monitor their health prior to seeking help. BMC Health Services Research 8(1), 56.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tsey K, Patterson D, Whiteside M, Baird L, Baird B (2002) Indigenous men taking their rightful place in society? A preliminary analysis of a participatory action research process with Yarrabah Men’s Health Group. Australian Journal of Rural Health 10(6), 278-284.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Wenitong M, Adams M, Holden CA (2014) Engaging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men in primary care settings. Medical Journal of Australia 200(11), 632-633.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |