Multidisciplinary primary care outreach for women experiencing domestic and family violence and/or homelessness: a rapid evidence review

Suzanne Lewis A * , Zoi Triandafilidis

A * , Zoi Triandafilidis  A , Mariko Carey

A , Mariko Carey  A B , Breanne Hobden

A B , Breanne Hobden  B , Colette Hourigan C Shannon Richardson D

B , Colette Hourigan C Shannon Richardson D

A

B

C

D

Abstract

Women and children who experience domestic and family violence (DFV) have complex physical and mental health needs, may be at risk of homelessness, and face substantial barriers to accessing health care. The integration of outreach primary health care delivered by a multidisciplinary team (MDT) into shelters or mobile clinics may address these issues. This rapid review sought to identify and describe outreach programs for women and children affected by DFV and/or homelessness in middle- and high-income countries.

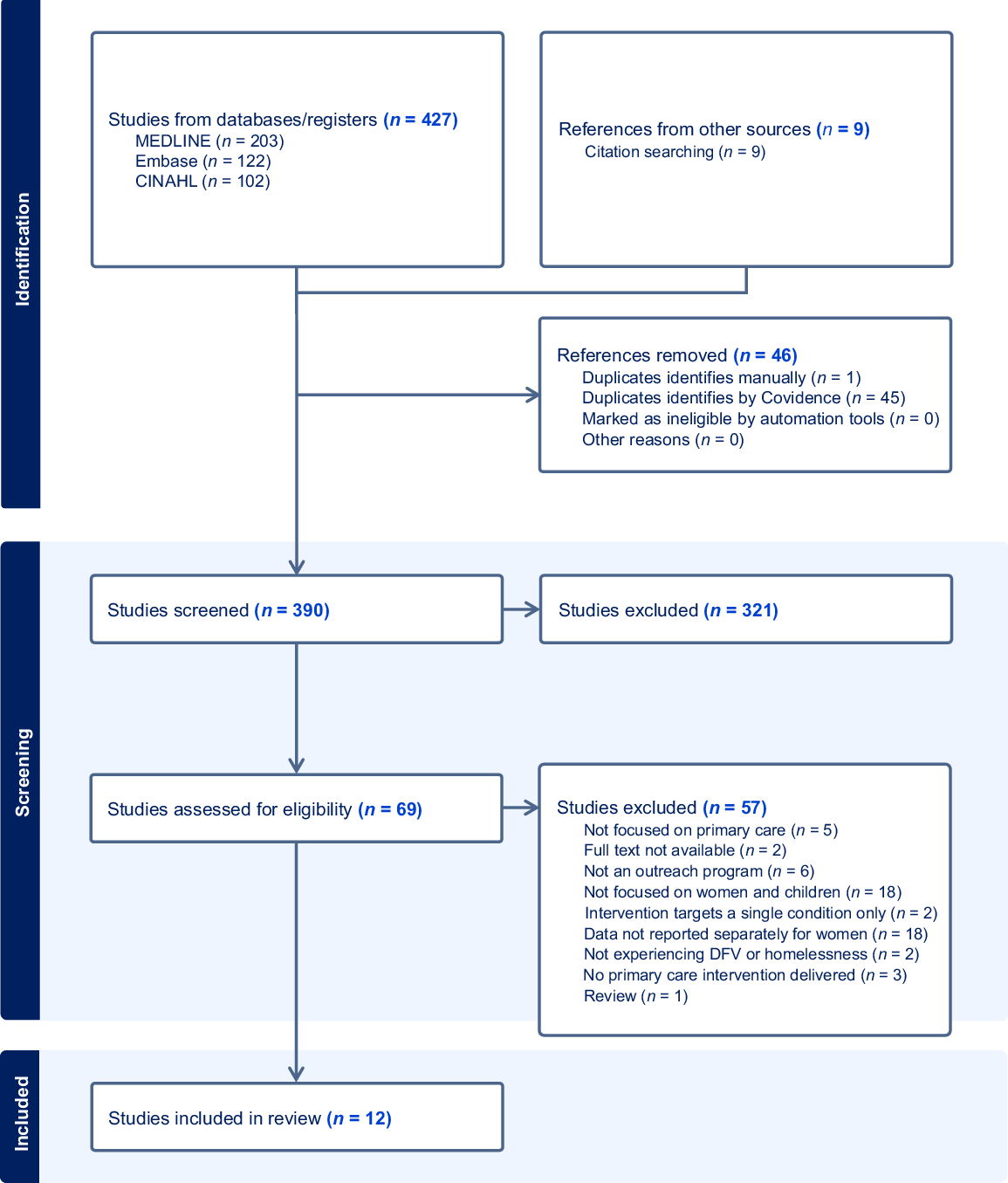

Seven bibliographic databases were searched in March 2024. Included studies described a primary care MDT outreach program that was delivered in a shelter, refuge, mobile clinic or drop-in centre; were written in English; and reported results separately for women.

Twelve publications reporting on 11 programs were included. These identified four staffing models: (1) nurse-led MDT; (2) nurse-led MDT with physician available remotely; (3) MDT with on-site physician; and (4) student-led. Model 3 offered the greatest range of services (11.5 on average), and Model 4 the least (5.5 on average). Three publications reported on two quasi-experimental studies, whereas the remainder of the studies lacked a control group. All studies reported benefits to outreach service clients for one or more of the following outcomes: service acceptability, healthcare use, health outcomes and economic outcomes. Only two studies examined the impact on health outcomes.

Few studies evaluate primary care MDT outreach programs; however, those identified in this review indicate benefits for women and children experiencing DFV and/or homelessness.

Keywords: domestic and family violence, health care accessibility, homelessness, integrated care, multidisciplinary team, outreach, primary health care, women and children.

Introduction

Domestic and family violence (DFV) is defined as violence that occurs within family relationships (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2024a), whereas intimate partner violence (IPV) specifically pertains to violence by current and former partners or spouses (World Health Organization 2024). Both DFV and IPV are significant health, social and economic issues worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that the global lifetime prevalence of IPV perpetrated against women aged 15–49 years is 27% (World Health Organization 2024). Globally, approximately one in six children are exposed to DFV as either victim, witness or both (Whitten et al. 2024). This review uses the term DFV as an umbrella term for IPV and other forms of family violence.

DFV greatly increases the risk of homelessness for women (Chan et al. 2021) and is the leading cause of homelessness for women in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2024b). Homelessness is defined as ‘living in either non-conventional accommodation or sleeping rough… [or] short-term or emergency accommodation due to a lack of other options (such as living temporarily with friends and relatives)’ (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2025a). In 2023–2024, 39% of all people receiving specialist homelessness services in Australia had experienced DFV; of those, 9 in 10 were either women 15 years and older or children aged 0–14 years (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2024b).

Homelessness is associated with acute and long-term health impacts such as poor nutrition, increased risk of injury and infectious disease, poor mental health and reduced life expectancy (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2025b). DFV also has both acute and long-term health impacts for women and their children (Potter et al. 2021; Whitten et al. 2022). Women who experience DFV are at increased risk of chronic conditions such as diabetes, chronic pain, alcohol and substance abuse, depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Dillon et al. 2013; Stubbs and Szoeke 2022). Children who are exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as DFV, are at increased risk of delays in reaching developmental milestones (Gartland et al. 2021) including language and literacy skills (Jimenez et al. 2016). They are also more likely to have unhealthy behaviours, poor mental health outcomes (Haslam et al. 2023) and develop chronic diseases in adulthood (Hughes et al. 2017; NSW Ministry of Health 2019; Gartland et al. 2021).

Despite the complex needs of women and children affected by DFV and those who are homeless, they often face barriers to accessing primary care. These include feeling safe to disclose concerns to healthcare professionals, knowing which services are available, difficulties processing and remembering information because of the impact of trauma and feeling judged by health professionals (Davies and Wood 2018; Hollingdrake et al. 2023). A recent scoping review has indicated that primary care nurses have limited knowledge of DFV practice guidelines and how to support people experiencing DFV (Aljomaie et al. 2022).

When women leave violent relationships, they may experience significant financial disadvantage, which further impedes their ability to prioritise health care, including an inability to pay for transport, appointments, or prescriptions (Hollingdrake et al. 2023). Similar financial and practical barriers have been reported for homeless populations (Davies and Wood 2018). Migrant and refugee women experiencing DFV often face further barriers including language, social isolation, fear of deportation and socio-cultural influences (Allen-Leap et al. 2022).

Primary care outreach services have been proposed as a way of improving access to care for those experiencing homelessness for any reason (Kopanitsa et al. 2023), but there is less evidence regarding such outreach services in DFV shelters (Mantler et al. 2020). Further, given the complexity of health problems faced by women and children who have experienced DFV and/or homelessness, multidisciplinary models of care may be warranted. A multidisciplinary team (MDT) is defined as practitioners from more than one health discipline and/or more than one organisation working together to deliver coordinated care (Mitchell et al. 2008).

The review by Mantler et al about the integration of primary care services in women’s DFV shelters, which searched the published literature up to 2017, identified just four studies (Mantler et al. 2020). In this review, primary care was broadly defined as services to improve physical and mental health including health promotion, and there was no specific focus on multidisciplinary models. The review identified that integration of services improved the accessibility and acceptability of health services and potentially reduced future health burden through participation in preventive care activities. Similarly, a recent review of outreach services for general homeless populations also revealed benefits in terms of improved access because of flexible appointments delivered in convenient locations, referrals and provision of basic resources (Kopanitsa et al. 2023). This review identified 24 studies and included primary care delivered by a range of disciplines such as general practice, community pharmacy, dental and optometry; however, it did not have a specific focus on multidisciplinary models of primary care. Further, the review did not include a focus on women or those who had experienced DFV.

The aim of the current review was to identify and describe MDT models of primary care outreach to women and their children affected by DFV and/or homelessness, in countries with comparable health and social care systems (i.e. middle- and high-income countries classified by The World Bank (2023)). Specifically, this review seeks to answer the following question: what are the settings, populations, staffing profiles, services delivered and outcomes reported for these models?

Methods

Design

A rapid review methodology was selected as the most appropriate, given the timeframe and resources available. The review was informed by the WHO guidance on rapid review methodology (Tricco et al. 2017). Results are reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines (Tricco et al. 2018).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Included publications were those which: (i) were concerned with women (with or without children) experiencing DFV and/or homelessness; (ii) reported at least some results for women and/or children separately to those of men; (iii) examined outreach care delivery settings including refuges, shelters, drop-in centres and mobile vans; (iv) examined outreach services delivered by a MDT of primary health professionals, which provided treatment for a broad range of health concerns; (v) were not limited to any study design; and (vi) were published in peer-reviewed journals in English.

Excluded publications were those which: (i) focused on men only or did not report any results separately for women (studies were not excluded if they did not report results separately for children); (ii) were not located in outreach settings; (iii) examined prevention or screening programs for DFV; (iv) focused on an outreach service for a single condition (e.g. HIV or hepatitis C); (v) examined an outreach service delivered by a single clinician without coordination with other health disciplines; (vi) were published as grey literature; and (vii) were not published in English or available in full text.

Search strategy

A search strategy was developed by one author [SL], an experienced health librarian, using search terms derived from previous reviews and suggested by the review team. The strategy, comprising both index terms and keywords used in combination with Boolean operators (OR, AND), was tested and refined in Medline (Ovid) before being translated for other databases. The search was run in the following databases in March 2024: Medline (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCO), Embase (Ovid), Google Scholar, the Cochrane Library, Campbell Collaboration and JBI EBP (Joanna Briggs Institute Evidence Based Practice database). The full search strategy for Medline (Ovid) is provided in Supplementary File 1. Backward and forward citation tracking was done for included studies.

Screening

Studies identified via database searches were exported to EndNote bibliographic management software (v.20, Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA) and then uploaded into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) where duplicates were removed. All authors screened a test set of 11 references, four of which being those identified by the review conducted by Mantler et al (2020). In this process, inclusion and exclusion criteria were refined and screening consistency was achieved by discussion as a group. All references underwent title/abstract and full-text screening by two independent reviewers. All authors participated in both screening stages. Conflicts were resolved by discussion between three or more members of the review team.

Data extraction and summary

The data extraction tool in Covidence was customised for use in the data extraction phase. Two authors (SL and ZT) developed the data extraction tool, which was tested by the remaining authors (MC, BH, CH and SR) before full use. All authors participated in data extraction. Extracted data included: (i) setting of the outreach program; (ii) population served by the program; (iii) staffing model; (iv) health and social care services offered; and (v) reported outcomes, including program feasibility and acceptability, usage, health outcomes and economic outcomes. Services offered by the programs were grouped according to the following headings: adult assessments; child assessments; treatment; preventive care and screening; referral, coordination and advocacy; psychosocial care; and other (e.g. practical help such as provision of clothes and nappies). The mean number of services offered by each staffing model was calculated. The extracted data are presented in tables and a narrative summary. As the main purpose of the review was to identify models of primary care outreach to women and children residing in DFV shelters and/or experiencing homelessness, a risk of bias assessment was not included (Tricco et al. 2017).

Results

A total of 427 references were retrieved from database searches and nine from citation searching. Following deduplication, 390 references were screened at the title and abstract stage, 65 of which were selected for full-text screening. Fifty-three studies were excluded, mainly because they were not focused on women and children (n = 18) or data were not reported separately for women and men (n = 18). Refer to the PRISMA diagram for the full list of exclusion reasons (Fig. 1). Twelve publications, reporting on 11 programs, were included in the review, the main features of which are summarised in Table 1.

| Reference (author, year and country). | Population and sample size | Services provided | Delivered by | Study design and evaluation measures | Main findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setting: DFV shelter | ||||||

| Attala and Warmington (1996) Illinois, USA | Women who had experienced DFV and their children residing at one 40-bed shelter. 69 surveys from women; 95 surveys completed for their children (age range 1 month to 16 years). | Where/when: shelter-based clinic (10 h per week). Services provided: comprehensive health assessment for women and children; a physical screening examination; health education; counselling and referrals. | Advanced practice nurses and social workers. Physicians off-site provided standing orders for some prescriptions. | Cross-sectional survey. 21-item study-specific survey assessing program impact for women (10 items), children (10 items) and one free-text question. | 95.5% of shelter clients surveyed had positive responses to the health services provided to them at the shelter; 96.7% had positive responses to the health services provided to their children. Written responses (n = 13) were generally positive; however, a few negative comments were received (e.g. ‘the nurse caused me to worry and did not treat me as an adult.’) | |

| D’Amico and Nelson (2008) Colorado, USA | 12 women (aged 21–52 years) and 3 children (aged 1, 9 and 14 years) who received a nurse case management intervention at a DFV shelter between 1 June and 1 August 2006. | Where/when: shelter-based clinic (2 h per week). Services provided: physical examinations, treatment of acute injuries and illnesses, mental health consultations, development of a post-shelter care plan, motivational interviewing, goal setting, and organising referrals to other service providers. | A registered nurse and a mental health care professional, employed by the shelter, and volunteer health professionals (nurses, physicians, physician assistants, and social workers). | Prospective chart audit. Service usage data were collected at point of delivery and 6 weeks post-intervention using the Care Management Outcomes Data Collection Sheet (items 1–5) and Barriers to Services Checklist (item 6). | The following services were recorded: (1) primary care referral 100% (n = 15) (accessed by 40% (n = 6)); (2) payer source referral (e.g. Medicaid) 100% (n = 15) (accessed by 40% (n = 6)); (3) specialty care referral 46.7% (n = 7) (accessed by 57% (n = 4)); (4) mental health referral 40% (n = 6) (accessed by 83.3% (n = 5)); (5) screening/preventative services (mammogram, immunisation) referral 13.3% (n = 2) (accessed by 100% (n = 2)); (6) Barriers to access/reasons for not attending included: leaving shelter without contact information (66.7%); forgetting appointment (22.2%); something else to do (11.1%). | |

| Mantler and Wolfe (2018) Ontario, Canada | Women experiencing trauma, including DFV, who were either housed at two shelters or using a drop-in clinic (n = 25); service administrators (n = 4) and service providers (n = 10). | Two models of social and primary care integration are examined. Model 1. Nurse Practitioner-led outreach clinicWhere/when: either at a shelter or community-based drop-in site, run weekly. Services provided: described as primary care services without further detail. Model 2. Rural women’s shelterWhere/when: at shelter Services provided: inhouse psychological services, children’s services, advocacy; and referrals out to the community for other primary care services. | Model 1 – Nurse Practitioner. Model 2 – Domestic violence advocates, counsellors, and referral to community for primary care services. | Qualitative. Data were collected via semi-structured interviews and field notes; thematic inductive content analysis was conducted. | Both models were highly acceptable and perceived to provide comprehensive, ‘wrap-around care’. Perceived impacts included strong partnerships and improved system navigation. For Model 1, facility integration and accessibility were noted as advantages. The model also functioned as ‘a bridge back to the health-care system’. Users of the facility-based services reported improvements in both physical and mental health. Limited resources and lack of trauma-informed care by other sectors were perceived as gaps for both models. Breaks in continuity in services in Model 1 was also noted as a limitation. | |

| Tschirch et al. (2006) East Texas, USA | Women who entered a DFV shelter and underwent health screening (n = 79). | Where/when: a clinic at the DFV shelter one day per week. Services provided: history, physical examination, laboratory samples, mental health assessment; the psychiatrist conducts a teleconference examination, starts treatment; medications are dispensed by the Psychiatric Nurse Practitioner (PNP), if prescribed. Teleconferences include the patient’s shelter liaison and the PNP; up to four teleconference clinic visits are offered before ongoing care is transferred to a specialist mental health centre. | Family Nurse Practitioner, PNP, and shelter liaison worker on site plus a psychiatrist providing telehealth appointments. | A cross-sectional survey using an unvalidated, locally developed instrument (East Texas Tele-mental Health Network Patient Satisfaction Data survey) evaluated client satisfaction. Service delivery data were also collected including diagnosis, telemedicine visits, referrals, emergency room visits and state mental hospital admissions pre- and post-implementation. | After screening, 38 women were referred for psychiatric evaluation; 35 of these (92%) completed an evaluation and 34 initiated treatment. 25 were treated successfully and referred for ongoing mental health care. 110 telemedicine visits were conducted; 97% of patients had mood and anxiety disorders, 54% had PTSD and 49% had major depression. During the 18-month project period, there was only one emergency room visit (compared to three to four per month prior to the program) and no admissions to the state mental hospital (compared to four to eight per year previously). The patient satisfaction survey results showed high levels of satisfaction with the telemedicine experience. The number of women who completed the survey was not reported. | |

| Setting: Homeless shelter | ||||||

| Burkeen (1994) Kentucky, USA | Families living in a small, family transitional shelter; nursing students on placement at the shelter. | Where/when: shelter-based nursing student clinical site for one semester. Services provided: identifying clients’ needs, helping clients to set goals, developing care plans, providing counselling and education, making referrals, and assisting clients to use their strengths to meet their own needs. | Community health nursing students. Local health centre physician provided remote medical review as needed. | The service is described but no evaluation was conducted. | Needs identified included: (1) lack of self-esteem; (2) PTSD; (3) substance abuse, (4) anxiety; (5) depression; (6) psychosomatic complaints; (7) child and spouse abuse; (8) anaemia; (9) malnutrition; (10) upper respiratory infections; (11) dental problems; (12) various chronic diseases; (13) immunisations; (14) developmental delays; (15) lack of parenting skills, and (16) need for family planning assistance. Interventions delivered included family planning education and referral, making dental referrals, education about early signs of labour, breastfeeding, and newborn care, providing over-the-counter drugs for diarrhoea and referral to an alcoholism treatment centre. | |

| Ciaranello et al. (2006) California, USA | Single adults (18 years or older) living in transitional housing facilities. 609 shelter residents participated in the study over 18 months. Women comprised 38% of participants at the four intervention sites and 22% at the two control sites (described as non-equivalent comparison sites). | Where/when: transitional housing facilities; intervention sites received weekly visits by an Integrated Service Team (IST) Services provided: comprehensive health assessments, follow up care, social work services, counselling, health education, referrals to dental services, specialty medical services, diagnostic studies, and brief problem-focused psychotherapy. An advice nurse was available by telephone 24 h a day. Additional clinics provided HIV and tuberculosis testing and influenza vaccinations. Control site residents received usual care. | A medical director, a nurse practitioner, a medical clerk, and a social worker. | Quasi-experimental, controlled before and after study. Statistical analysis used a standard pre-test, post-test analysis of covariance (ANACOVA) adapted to deal with the challenges presented by the data. Interviewer-administered surveys plus brief physical examinations were conducted at baseline, 6 months, and 18 months post-intervention. The only results reported separately for women were uptake of screening. | At 18 months, female residents at intervention sites had a higher tendency than residents at comparison sites to report having had a Pap smear in the past year, after adjusting for site-specific baseline effects. No significant difference was discovered between the intervention and comparison groups for having had a mammogram in the previous 2 years. | |

| DiMarco (2000) Ohio, USA | Children (n = 4) residing at a homeless shelter specifically for women and children. | Where/when: on site clinic for all children entering the shelter; duration and frequency not reported. Services provided: physical and developmental screening, primary health care, referrals and facilitated access to other health care services, treatment of minor conditions, screening for indications of abuse and health education for mothers. Support was also provided in scheduling appointments both in clinic and with other providers and obtaining immunisation records. | College of Nursing faculty operating as Advanced Practice Paediatric Nurses; graduate nurses, nursing and medical students, a Care Clinic Liaison officer. A local paediatrician provides standing orders for medications, telephone consultations, shelter visits, chart reviews and referrals to hospital. | Case series (n = 4). | Case study 2: Dana, 8-month-old female with a 4-year-old brother and mother diagnosed with depression. Children were not up to date with immunisations and concerns about physical and developmental abnormalities were identified. Referral to the local children’s hospital resulted in differential diagnoses of torticollis, craniosynostosis, and possible cerebral palsy. A subsequent urgent referral to a neurologist was organised but the mother left the shelter before the appointment. The Paediatric Nurse and mother’s case worker subsequently accompanied the family to the appointment. Extensive physical therapy was initiated; after 4 months Dana was progressing with physical milestones. | |

| Graham-Jones et al. (2004) Liverpool, UK See the related study below: Reilly et al. (2004) | Homeless people residing in hostels, shelters, bed and breakfast hotels or other temporary accommodation. Most participants in the study were women (72%), 41% of whom were living with their children. Numbers of children were not reported separately. | Where/when: temporary accommodation or health centre. Services provided:Arm 1. Usual care from a GP at a health centre (GP practice). Arm 2. Health advocacy without outreach. Residents were supported to register with a health centre. Once registered, usual care. Arm 3. Health advocacy with outreach by a Family Health Worker (FHW). In addition to support in registering with a health centre, families were provided with health checks and education, practical help (e.g. organising clothes, baby equipment); and liaision with other health and social services. | A FHW employed as part of the primary health care team (GP, health centre nurses). The FHW was a qualified Registered General Nurse and Registered Mental Health Nurse with extensive community experience. | Quasi-experimental three-armed controlled trial. Participants were allocated in alternating periods of 1–3 months to one of three arms: (1) usual care; (2) health advocacy without outreach; (3) health advocacy with outreach. Interview and questionnaires were completed at baseline and after 3 months. Instruments used were: The Life Fulfilment Scale (LFS); The Delighted–Terrible Faces Scale (DTFS) to assess global quality of life; and the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) to measure distress and subjective health. | Of 326 clients given baseline questionnaires, 222 (68%) returned usable questionnaires. Of these, 171 (77%) were traceable at follow up; of those 171 individuals, 117 (68.4%) returned follow up questionnaires. Compared to usual care, clients in the two intervention arms reported greater improvements on the Life Fulfilment Scale, The Delighted Terrible Faces and the Nottingham Health Profile. The greatest improvement was observed in the health outreach with advocacy group (Arm 3). The largest effect sizes were seen in improvements in: ‘being happy with oneself” (mean difference = 3.09, 95% CI = 1.30–4.87; Bonferroni-corrected P < 0.001) and ‘emotional distress’ (mean difference = 25.89, CI = 7.96–43.83; Bonferroni-corrected P < 0.01). The authors suggest that early outreach contact by the FHW was a key factor for people in Arms 2 and 3 of the study. | |

| Reilly et al. (2004) See the related study above: Graham-Jones et al. (2004) | See above. 400 adults, 76% of whom were women. | See above. | See above. | Quasi-experimental three-armed controlled trial (see above). Health service utilisation and cost data for 400 adults over 3 months were extracted from primary care case notes. Intention-to-treat analysis was used to identify between-group differences. | Participants in the outreach advocacy group (Arm 3) had significantly more patient-initiated (P = 0.017) and advocate-initiated (P = 0.004) contacts than the health centre advocacy group. Participants in the outreach advocacy group (Arm 3) made significantly less use of health centre resources compared to the health centre advocacy group (Arm 2) and the usual care group (Arm 1), including fewer GP contacts and medication prescriptions. Primary care workload costs for each group (£/mean cost per adult) were: usual care (Arm 1) – 70.64; health centre advocacy (Arm 2) – 64.86; outreach advocacy (Arm 3) – 46.55. When the cost of Family Health Worker consultations was added to the two advocacy groups, mean costs per adult were: health centre advocacy (Arm 2) – 80.58; outreach advocacy (Arm 3) – 71.69. Additional costs of health advocacy were offset by the reduction in demand for health centre resources. | |

| Stevens (2002) Minneapolis, USA | Homeless women and children residing in a 50-bed family homeless shelter. | Where/when: a shelter-based clinic two mornings per week; dental clinic one morning per week; and student nurse-led weekly health promotion preschool, plus occasional ‘health fair’. Services provided: nursing students diagnosed and referred children to the clinic for treatment of conditions such as head lice, impetigo, and upper respiratory tract infections. | A paediatric and adult nurse practitioner, a volunteer dentist, and undergraduate nursing students. | No formal evaluation reported. | A few outcomes of the student nurse-led activities are reported for the shelter residents (e.g. after the first health fair, 3/20 adults who attended were started on antihypertensive medication and one was enrolled in a smoking cessation program). | |

| Setting: Mobile outreach | ||||||

| Busen and Engebretson (2008) Texas, USA | Youth aged 15–25 years who used a medical mobile unit that provided health services to homeless and street-involved young people (n = 95). Of the sample, 51 (54%) were female with a mean age of 20.4 years. | Where/when: a mobile unit two evenings per week in an area where homeless young people gather regularly. Services provided: physical and mental health assessments, treatment of minor illnesses and injuries, prescriptions, screening, vaccinations, referrals to low or no cost agencies. | Team comprising a psychiatrist, adolescent medicine fellow, nurse practitioners, social worker, counsellor, support staff and community outreach workers. | Retrospective chart audit. Records were audited for the following US Department of Health and Human Services risk reduction health indicators: updated immunisations; adherence to medical and mental health treatment, follow up, and referral; adherence to prescribed medications; treatment for, or decreased, substance abuse; and responsible sexual behaviour. | For all participants, mean time of engagement with the mobile unit was 14 months. Most frequent medical interventions for females were: STI screening, STI treatment, follow up and referral for medical/dental conditions, viral screening (hepatitis, HIV, HPV), immunisations, and Pap smears. Overall outcomes of medical treatments provided to females, measured by improvements against risk reduction indicators, were: 88.2% improved, 11.7% no information. Overall outcomes of mental health interventions provided to females (counselling, medication stabilised, hospitalisation) were: 74.5% improved, 17.6% no information, 5.8% worse, 1.9% no change. | |

| Paradis-Gagné et al. (2023) Montreal, Canada | A convenience sample of people who are currently (or have) experienced homelessness and who use the services of a mobile health clinic (n = 12). | Where/when: mobile health unit, frequency and duration of clinics not reported. Services provided: primary care, wound care, sexually transmitted disease screening and blood tests, distribution of safe injection equipment and condoms, and referrals to other medical clinics. | A team of nurses, street workers (this role is not defined) and volunteers. | Qualitative study using critical ethnography with data collection via semi-structured interviews and 60 h of observation during clinics. | Results were reported according to three categories: worrisome health and social needs; non-use of health care; and what connects us to health services. Two out of 12 participants (16.6%) were women, both were Indigenous. They reported being treated kindly at the mobile van service. One of the women reported that being able to bring her caseworker to the clinic and/or health service/s made her feel more at ease. During observation of the service, women were heard to appreciate the ‘safe space’ aspect of the clinic. | |

Location and population

Eight of the publications reported on programs from the United States, and two each from Canada and the United Kingdom. Ten out of the 12 included publications provided some detail on the ethnicity of the target population. Most outreach service recipients were white (American, Canadian, or British), although US programs also reported African American, Hispanic, Puerto Rican and Native American client populations. One Canadian study (Paradis-Gagné et al. 2023) reported 2 out of 12 participants being Indigenous women who spoke both Inuktut and English.

Settings

Four publications focused on women and children who had experienced DFV, with the location being a DFV shelter or refuge (Attala and Warmington 1996; Tschirch et al. 2006; D’Amico and Nelson 2008; Mantler and Wolfe 2018). Eight publications focused on women, youth, children, or families experiencing homelessness, either residing in homeless shelters or transitional housing (Burkeen 1994; DiMarco 2000; Stevens 2002; Graham-Jones et al. 2004; Reilly et al. 2004; Ciaranello et al. 2006) or using the services of an outreach clinic located in a mobile van (Busen and Engebretson 2008; Paradis-Gagné et al. 2023).

Study designs

Three studies used quasi-experimental designs (Graham-Jones et al. 2004; Reilly et al. 2004; Ciaranello et al. 2006). The remaining study designs comprised two cross-sectional survey studies (Attala and Warmington 1996; Tschirch et al. 2006), one retrospective chart audit (Busen and Engebretson 2008), one prospective chart audit (D’Amico and Nelson 2008), two qualitative studies (Mantler and Wolfe 2018; Paradis-Gagné et al. 2023), and a case series (DiMarco 2000). Two publications provided program descriptions only, without evaluation (Burkeen 1994; Stevens 2002).

Staffing

Six of the outreach programs described were delivered by a nurse-led MDT (Stevens 2002; Reilly et al. 2004; Graham-Jones et al. 2004; D’Amico and Nelson 2008; Mantler and Wolfe 2018; Paradis-Gagné et al. 2023); four were delivered by nurse-led MDTs with a physician available remotely, most often for prescriptions or consultations (Burkeen 1994; Attala and Warmington 1996; DiMarco 2000; Tschirch et al. 2006); and two services were provided by MDTs that included an on-site physician (Ciaranello et al. 2006; Busen and Engebretson 2008). Three of the programs were provided as part of undergraduate nursing courses and involved other health disciplines as well as nursing (Burkeen 1994; DiMarco 2000; Stevens 2002). All of the services included nurses, usually holding advanced practice qualifications in family health, community health, mental health or child and adolescent health. Where a medical practitioner was available either on site or remotely, this role was filled by family physicians, psychiatrists or paediatricians. One service included a dentist (Stevens 2002). Other staff included social workers, counsellors, community outreach workers, medical clerks and administration support workers. Some teams comprised paid and volunteer health professional roles. Further detail about MDT roles is provided in Table 1.

Services provided

The main services provided by the outreach programs are summarised in Table 2, grouped according to the staffing model in place, namely, nurse-led MDT (Model 1), nurse-led MDT with remote access to a physician (Model 2), MDT with physician on site (Model 3), and student-led (Model 4). Of the 11 programs reported in the publications, 10 included physical health assessments for adults and/or children and referral to other providers. One publication did not provide sufficient information on the services provided (Mantler and Wolfe 2018). Mental health assessments for adults were less commonly offered than physical health assessments. Screening for child abuse was offered in two of the programs that included either a remote or onsite physician. All except one program reported offering referrals to other health providers. Seven programs, five of which were nurse-led models, offered practical help with making and attending appointments; five programs, of which four were nurse-led, reported offering advocacy and liaison with non-health service providers such as social or legal services. Three of the five nurse-led MDTs offered other practical support such as providing clothing and nappies. This service was not reported as being provided by the other two nurse-led MDTs or by the programs using the other staffing models. Four of the five programs that involved a remote or onsite physician reported provision of prescription medications. Counselling interventions were available in seven programs; and brief problem-focused psychotherapy in one. Psychiatric treatment was provided in one nurse-led with remote physician program and one MDT with on-site physician program. Programs using Model 3, involving a MDT with physician on site, offered the greatest range of services with 11.5 on average. Programs using Model 4, involving student-led support, offered the least with 5.5 services on average.

| Service | Model 1: nurse-led MDT | Model 2: nurse-led MDT with remote physician | Model 3: MDT with physician on site | Model 4: student-led | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D’Amico and Nelson (2008) | Graham-Jones et al. (2004) | Mantler and Wolfe (2018) A | Paradis-Gagné et al. (2023) | Reilly et al. (2004) | Attala and Warmington (1996) | DiMarco (2000) | Tschirch et al. (2006) | Busen and Engebretson (2008) | Ciaranello et al. (2006) | Burkeen (1994) | Stevens (2002) | ||

| Adult assessments | |||||||||||||

| Physical health assessments | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | ||

| Mental health assessment | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | ||||||

| Child assessments | |||||||||||||

| Physical health assessment | Y | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y | NA | Y | |||

| Developmental assessment | NA | Y | Y | NA | NA | Y | |||||||

| Screening for child abuse | NA | Y | NA | Y | NA | ||||||||

| Treatment | |||||||||||||

| Treatment of illnesses and minor injuries (including over-the-counter medications) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||

| Prescriptions (medications) | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||||||

| Preventive care and screening | |||||||||||||

| Health screening (e.g. Pap smears) | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||||||

| Communicable disease testing | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||||||

| Vaccinations | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Health education | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||||

| Referral, co-ordination and advocacy | |||||||||||||

| Referrals to other health providers (e.g. substance abuse clinics) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Practical help making and attending appointments | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||

| Advocacy and liaison with service providers outside health (e.g. social services, legal services) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||

| Psychosocial care | |||||||||||||

| Counselling, motivational interviewing and goal setting | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||

| Brief problem-focused psychotherapy | Y | ||||||||||||

| Treatment of psychiatric conditions (e.g. PTSD, anxiety) | Y | Y | |||||||||||

| Other | |||||||||||||

| Other practical help (clothes, nappies, etc.) | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Total | 6 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 6 | 12 | 11 | 7 | 4 | |

Outcomes

Across the 10 publications that included program evaluations, the examined outcomes included acceptability, healthcare use, health outcomes and economic outcomes. All studies reported benefits to outreach service clients for one or more of these outcomes.

Four studies examined service acceptability via client surveys (Attala and Warmington 1996; Tschirch et al. 2006) and semi-structured interviews (Mantler and Wolfe 2018; Paradis-Gagné et al. 2023), finding that the outreach programs were valued for safety, convenience and comprehensiveness of care. One study reported perceived harms with negative comments about a nurse-led clinic offered in a DFV shelter; for example, ‘the nurse caused me to worry and did not treat me as an adult’ (Attala and Warmington 1996). Because of the heterogeneity across the studies and non-standardised survey instruments and interview guides, it was not possible to directly compare acceptability levels between the nurse-led services (Model 1: Mantler and Wolfe 2018; Paradis-Gagné et al. 2023) and the nurse-led with remote physician services (Model 2: Attala and Warmington 1996; Tschirch et al. 2006).

Four studies examined changes in health service usage. D’Amico and Nelson (2008) reported on outcomes of a case management intervention delivered to 12 women and three children in a DFV shelter, finding via a chart audit, that 40% of referrals to a primary care provider resulted in an appointment booked and attended, as did 57% of referrals for specialist care, and 83% of referrals to mental health care. Ciaranello et al. (2006) conducted a controlled before and after study and found that after 18 months of weekly outreach visits to transitional housing facilities for people experiencing homelessness, female residents at intervention sites were more likely than residents at comparison sites to report having had a Pap smear in the past year, although no difference was found for mammograms. Tschirch et al. (2006) evaluated a psychiatric telehealth service in a DFV shelter and found emergency department visits from the shelter decreased from an average of three to four per month to one visit over the 18-month intervention period. Reilly et al. (2004) examined health service utilisation data and found that homeless families in temporary accommodation who received a health advocate outreach model of care made significantly less use of health centre resources than those who did not receive the outreach service. Because of the limited number of studies and heterogeneity in measurement of health service usage between included studies, it was not possible to ascertain differences in usage between the nurse-led services (Model 1: Reilly et al. 2004; D’Amico and Nelson 2008), the nurse-led with remote physician service (Model 2: Tschirch et al. 2006), and the MDT with onsite physician service (Model 3: Ciaranello et al. 2006).

Two studies examined the impact of outreach programs on health outcomes. Graham-Jones et al. (2004) examined health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for homeless families receiving either usual GP care, advocacy without outreach or advocacy with outreach over 3 months and found that the greatest improvement was observed in the group receiving the health advocacy with outreach intervention. The largest effect sizes were seen in improvements in ‘being happy with oneself’ and reductions in ‘emotional distress’. Busen and Engebretson’s (2008) retrospective chart audit of 95 homeless youth using a mobile health service found that for women and girls, there was improvement in physical health for 88.2% of clients and in mental health for 74.5%, as measured by treatment compliance and notations by professional staff in medical records.

One study performed an economic analysis of an outreach health advocate linking homeless people in temporary accommodation with a primary health centre and found that the additional costs of the advocate’s role were offset by a reduction in demand for health centre services (Reilly et al. 2004). Services measured and costed included GP contacts, prescriptions and referral letters.

Discussion

This review sought to examine and synthesise the literature on primary care outreach programs for women and children experiencing DFV and/or homelessness. The 12 articles included in this review describe programs delivered in three main settings: DFV shelters, homeless shelters/temporary accommodation and mobile clinics. These programs provided a range of services delivered by four different staffing models. Outreach programs were generally reported to be acceptable to and valued by clients; however, their impact on healthcare use and health outcomes was unclear.

Clients appreciated the accessibility of the programs, including the convenience of care delivered at no charge in shelters or mobile vans (Attala and Warmington 1996; Tschirch et al. 2006; Mantler and Wolfe 2018; Paradis-Gagné et al. 2023). Within each staffing model, there was considerable heterogeneity in the services offered, which may reflect a combination of both client needs in each setting and local resources available. Models that included physicians were able to provide prescription medications and psychiatric treatment, both of which were highly valued (Attala and Warmington 1996; DiMarco 2000; Tschirch et al. 2006; Busen and Engebretson 2008). The findings of Kopanitsa et al.’s (2023) scoping review of primary health care service outreach to homeless populations support the need for on-site authorised prescribers (such as physicians or nurse practitioners) to provide and maintain pharmaceutical treatments.

Clients appreciated being treated kindly, without judgment, and regarded the clinics as safe spaces (Attala and Warmington 1996; DiMarco 2000; Tschirch et al. 2006; Mantler and Wolfe 2018; Paradis-Gagné et al. 2023). These findings are similar to those of Mantler et al. (2020) who found that care delivered in this way increased access to, and acceptability of, services and had the potential to act as a ‘bridge back to health-care’ for women and children affected by DFV.

Two studies examined the impact of outreach services on health outcomes (Graham-Jones et al. 2004; Busen and Engebretson 2008), and only one of these (Graham-Jones et al. 2004) was a controlled study. Different outcomes were examined across the two studies making it difficult to draw strong conclusions about effectiveness in improving health outcomes

Four studies examined health service usage outcomes, with some evidence of clients taking up referrals to other health services after receiving outreach care (Burkeen 1994; DiMarco 2000; Tschirch et al. 2006; D’Amico and Nelson 2008). Help from a health care advocate was found to decrease use of GP services, presumably because some primary care needs were being met through the advocacy service (Reilly et al. 2004). One study found that outreach clients had an increased uptake of some but not all preventive care services (Ciaranello et al. 2006); while another study found a decrease in emergency presentations over time (Tschirch et al. 2006). Overall, the included studies suggest positive impacts on health outcomes and health service use but are limited by the research designs used and potentially non-rigorous data collection methods.

This review, like that conducted by Mantler et al. (2020), identified very little published research on primary care outreach programs operating specifically in DFV shelters. Although there were further studies examining outreach programs in homeless shelters or mobile vans in the literature, most of these studies did not report results separately for women and therefore did not meet the inclusion criteria for this review. The small volume of research may be because of challenges that may be experienced when conducting research with this vulnerable population. Women and their children who have experienced DFV and/or are homeless are, by definition, a transient population that makes longitudinal studies difficult (Graham-Jones et al. 2004; Reilly et al. 2004). Not only does this result in substantial loss to follow up, it also has implications for the timing of follow-up periods, which may be too short to allow the effects of interventions to become apparent. Some of the studies included in this review use strategies including considering timing and data collection methods carefully during the research design. For example, Attala and Warmington (1996) distributed surveys or other evaluation tools prior to participants departing a shelter. In the quasi-experimental studies, interventions were assigned by site rather than individual level (Ciaranello et al. 2006), or in 1–3 month blocks of participants (Graham-Jones et al. 2004; Reilly et al. 2004).

The findings of this review are reflective of aspects of existing research with vulnerable populations such as those who have experienced DFV (Spangaro et al. 2009; Menih 2023). For example, Howarth et al. (2015) have called for a wider range of outcomes to assess interventions for children exposed to DFV, identifying that children, parents and health practitioners define success more broadly than the health-focused outcomes commonly measured.

This review addresses a gap in the literature as it focuses on outreach models of care delivered by MDTs and provides detailed information about settings, populations served, staffing profiles, organisation and administration, services offered and outcomes reported, which may prove useful to healthcare managers and commissioning bodies setting up similar models of outreach primary care.

Limitations of the study

This study found limited published literature on the topic of primary care outreach services for women and children experiencing DFV and/or homelessness. Despite careful development of the search strategy, searching seven databases including Google Scholar and conducting citation searching for the included studies, some relevant studies may have been missed. Time and resource constraints prevented a comprehensive search of the grey literature, which may have yielded additional relevant material. Although the review had a similar scope to a previous scoping review by Mantler et al. (2020), only two studies included in the current review were also examined by Mantler et al. (Attala and Warmington 1996; Tschirch et al. 2006).

It was not possible to compare outcomes by staffing model beause of the inconsistent and limited outcomes reporting across the included studies. Likewise, it was not possible to directly compare components of the models of care as some studies had scant detail about the model being examined. Although this limited the synthesis of study outcomes, these findings represent a clear need for improved rigorous research on this topic, supported by validated outcome measures and reporting frameworks.

Conclusion

There is a paucity of studies examining the impact of primary care outreach models for women and children who are homeless and/or residing in DFV shelters. The available evidence suggests that these models are acceptable and valued by women and assist in linking women to a range of health and other services. Although benefits and acceptability were reported across all of the included studies, only two studies directly examined health outcomes, finding some evidence for improvement. It is important for future research to ensure that health outcomes and improvements are measured as part of the evaluation process to substantiate the care models being delivered in this field.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were generated or analysed during this study.

Conflicts of interest

Dr Colette Hourigan was the lead general practitioner for the Hunter New England Central Coast Primary Health Network (HNECCPHN) pilot primary care outreach program; Ms Shannon Richardson commissioned the evaluation of the pilot on behalf of the HNECCPHN.

Declaration of funding

This review was funded as part of a mixed methods evaluation of the Hunter New England Central Coast Primary Health Network’s (HNECCPHN) pilot primary care outreach program in three domestic and family violence shelters on the Central Coast of New South Wales, Australia.

References

Aljomaie HAH, Hollingdrake O, Cruz AA, Currie J (2022) A scoping review of the healthcare provided by nurses to people experiencing domestic violence in primary health care settings. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances 4, 100068.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Allen-Leap M, Hooker L, Wild K, Wilson IM, Pokharel B, Taft A (2022) Seeking help from primary health-care providers in high-income countries: a scoping review of the experiences of migrant and refugee survivors of domestic violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 24(5), 3715-3731.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Attala JM, Warmington M (1996) Clients’ evaluation of health care services in a battered women’s shelter. Public Health Nursing 13(4), 269-275.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2024a) Family, domestic and sexual violence: FDSV summary. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra, ACT, Australia. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/family-domestic-and-sexual-violence/resources/fdsv-summary [Verified 13 November 2024]

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2024b) Family, domestic and sexual violence: economic and financial impacts. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra, ACT, Australia. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/family-domestic-and-sexual-violence/responses-and-outcomes/economic-financial-impacts [Verified 13 November 2024]

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2025a) Specialist homelessness services annual report 2023-24. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra, ACT, Australia. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/homelessness-services/specialist-homelessness-services-annual-report/contents/about [Verified 11 May 2025]

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2025b) Health of people experiencing homelessness. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Canberra, ACT, Australia. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/health-of-people-experiencing-homelessness [Verified 4 August 2025]

Burkeen OE (1994) Learning experiences in a rural family homeless shelter. Journal of Nursing Education 33(1), 43-44.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Busen NH, Engebretson JC (2008) Facilitating risk reduction among homeless and street-involved youth. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 20(11), 567-575.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Chan CS, Sarvet AL, Basu A, Koenen K, Keyes KM (2021) Associations of intimate partner violence and financial adversity with familial homelessness in pregnant and postpartum women: a 7-year prospective study of the ALSPAC cohort. PLoS ONE 16(1), e0245507.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ciaranello AL, Molitor F, Leamon M, Kuenneth C, Tancredi D, Diamant AL, Kravitz RL (2006) Providing health care services to the formerly homeless: a quasi-experimental evaluation. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 17(2), 441-461.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

D’Amico JB, Nelson J (2008) Nursing care management at a shelter-based clinic. Professional Case Management 13(1), 26-36.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Davies A, Wood LJ (2018) Homeless health care: meeting the challenges of providing primary care. Medical Journal of Australia 209(5), 230-234.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Dillon G, Hussain R, Loxton D, Rahman S (2013) Mental and physical health and intimate partner violence against women: a review of the literature. International Journal of Family Medicine 2013(1), 313909.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

DiMarco MA (2000) Faculty practice at a homeless shelter for women and children. Holistic Nursing Practice 14(2), 29-37.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Gartland D, Conway LJ, Giallo R, Mensah FK, Cook F, Hegarty K, Herrman H, Nicholson J, Reilly S, Hiscock H, Sciberras E, Brown SJ (2021) Intimate partner violence and child outcomes at age 10: a pregnancy cohort. Archives of Disease in Childhood 106(11), 1066.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Graham-Jones S, Reilly S, Gaulton E (2004) Tackling the needs of the homeless: a controlled trial of health advocacy. Health & Social Care in the Community 12(3), 221-232.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Haslam D, Mathews B, Pacella R, Scott J, Finkelhor D, Higgins D, Meinck F, Erskine H, Thomas H, Lawrence D, Malacova E (2023) The prevalence and impact of child maltreatment in Australia: findings from the Australian Child Maltreatment Study. Brief report. Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. Available at https://www.acms.au/resources/the-prevalence-and-impact-of-child-maltreatment-in-australia-findings-from-the-australian-child-maltreatment-study-2023-brief-report/ [Verified 13 November 2024]

Hollingdrake O, Saadi N, Alban Cruz A, Currie J (2023) Qualitative study of the perspectives of women with lived experience of domestic and family violence on accessing healthcare. Journal of Advanced Nursing 79(4), 1353-1366.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Howarth E, Moore THM, Shaw ARG, Welton NJ, Feder GS, Hester M, MacMillan HL, Stanley N (2015) The effectiveness of targeted interventions for children exposed to domestic violence: measuring success in ways that matter to children, parents and professionals. Child Abuse Review 24(4), 297-310.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Hughes K, Bellis MA, Hardcastle KA, Sethi D, Butchart A, Mikton C, Jones L, Dunne MP (2017) The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health 2(8), e356-e366.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Jimenez ME, Wade R, Jr, Lin Y, Morrow LM, Reichman NE (2016) Adverse experiences in early childhood and kindergarten outcomes. Pediatrics 137(2), e20151839.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kopanitsa V, McWilliams S, Leung R, Schischa B, Sarela S, Perelmuter S, Sheeran E, d’Algue LM, Tan GC, Rosenthal DM (2023) A systematic scoping review of primary health care service outreach for homeless populations. Family Practice 40(1), 138-151.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Mantler T, Wolfe B (2018) Evaluation of trauma-informed integrated health models of care for women: a qualitative case study approach. Partner Abuse 9(2), 118-136.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mantler T, Jackson KT, Walsh EJ (2020) Integration of primary health-care services in women’s shelters: a scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 21(3), 610-623.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Menih H (2023) Challenges and complexities when researching vulnerable populations and sensitive topics: working with women experiencing violence and homelessness. In ‘Fieldwork experiences in criminology and security studies’. (Eds AM Díaz-Fernández, C Del-Real, L Molnar) pp. 119–140. (Springer: Cham) doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-41574-6_7

Mitchell GK, Tieman JJ, Shelby-James TM (2008) Multidisciplinary care planning and teamwork in primary care. Medical Journal of Australia 188(S8), S61-S64.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

NSW Ministry of Health (2019) The first 2000 days framework. NSW Ministry of Health: North Sydney, NSW, Australia. Available at https://www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/ActivePDSDocuments/PD2019_008.pdf [Verified 13 November 2024]

Paradis-Gagné E, Jacques M-C, Pariseau-Legault P, Ben Ahmed HE, Stroe IR (2023) The perspectives of homeless people using the services of a mobile health clinic in relation to their health needs: a qualitative study on community-based outreach nursing. Journal of Research in Nursing 28(2), 154-167.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Potter LC, Morris R, Hegarty K, García-Moreno C, Feder G (2021) Categories and health impacts of intimate partner violence in the World Health Organization multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. International Journal of Epidemiology 50(2), 652-662.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Reilly S, Graham-Jones S, Gaulton E, Davidson E (2004) Can a health advocate for homeless families reduce workload for the primary healthcare team? A controlled trial. Health & Social Care in the Community 12(1), 63-74.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Spangaro J, Zwi AB, Poulos R (2009) The elusive search for definitive evidence on routine screening for intimate partner violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 10(1), 55-68.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Stevens MS (2002) Community-based child health clinical experience in a family homeless shelter. Journal of Nursing Education 41(11), 504-506.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Stubbs A, Szoeke C (2022) The effect of intimate partner violence on the physical health and health-related behaviors of women: a systematic review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 23(4), 1157-1172.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

The World Bank (2023) The world by income and region. (The World Bank: Washington, USA) Available at https://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/the-world-by-income-and-region.html [Verified 11 May 2025]

Tricco AC, Langlois EV, Straus SE (2017) Rapid reviews to strengthen health policy and systems: a practical guide. (World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland) Available at https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/258698/9789241512763-eng.pdf [Verified 16 November 2024]

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tunçalp Ö, Straus SE (2018) PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 169(7), 467-473.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Tschirch P, Walker G, Calvacca LT (2006) Nursing in tele-mental health. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 44(5), 20-27.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Whitten T, Green MJ, Tzoumakis S, Laurens KR, Harris F, Carr VJ, Dean K (2022) Early developmental vulnerabilities following exposure to domestic violence and abuse: findings from an Australian population cohort record linkage study. Journal of Psychiatric Research 153, 223-228.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Whitten T, Tzoumakis S, Green MJ, Dean K (2024) Global prevalence of childhood exposure to physical violence within domestic and family relationships in the general population: a systematic review and proportional meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 25(2), 1411-1430.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

World Health Organization (2024) Violence against women. (World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland) Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women [Verified 16 November 2024]