Healthcare workers’ perspectives on the implementation of tuberculosis infection prevention and control policy in rural Papua New Guinea

Gigil Marme A * , Jerzy Kuzma A , Peta-Anne Zimmerman B , Shannon Rutherford C Neil Harris D

A * , Jerzy Kuzma A , Peta-Anne Zimmerman B , Shannon Rutherford C Neil Harris D

A

B

C

D

Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) infection prevention and control (TB-IPC) is recommended as an essential public health intervention to control TB transmission worldwide. Nonetheless, merely applying evidence-based prevention and control measures is often inadequate for effective TB prevention and treatment goals. This study examined healthcare workers’ (HCWs’) perceptions of strategies important for TB-IPC in primary healthcare (PHC) settings in Papua New Guinea.

Using a nominal group technique, this study sought the views of a diverse range of HCWs (ranging from clinical, IPC personnel to policymakers) from national and subnational levels, and various provinces to prioritise TB-IPC guidelines implementation needs in practice. Group discussions were conducted with 51 HCWs, and encompassed quantitative and qualitative data collection techniques. Nine key strategies drawn from a preceding study and literature review were presented to participating HCWs, and from these, three significant strategies related to TB-IPC policy were identified as key priorities.

The participants recommended HCWs’ capacity building on TB-IPC policy and strategy, improving PHC infrastructure, and increasing community awareness of TB as the most important strategies to improve TB-IPC practices.

This study investigated the perceptions of diverse key HCWs of the implementation of TB-IPC guidelines in PHC settings in rural Papua New Guinea. The HCWs identified key strategies needed for effective TB-IPC practice in PHC to prevent TB transmission. This study supports previous recommendations that call for adopting multi-pronged strategies to improve the high TB burden. Key stakeholders’ insights have been shared to inform public health policy and program implementation both locally and as part of the global goals of the TB eradication program.

Keywords: community health, healthcare workers, infection prevention and control, nominal group technique, Papua New Guinea, primary health services, rural health services, rural hospitals, TB control strategies, tuberculosis.

Introduction

Before the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (COVID-19), infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis was the leading cause of death from a single infectious disease worldwide (Falzon et al. 2023). Although Papua New Guinea (PNG) has transitioned out of the 30 countries with a high tuberculosis (TB)/HIV burden, there was an extremely high TB incidence of 432 per 100,000 in 2023, and the case fatality rate among HIV-negative people with TB was 27 per 100,000 (World Health Organization 2023). Among nationally reported TB cases, it was estimated that 3.4% of new TB patients and 26% of previously treated cases had multidrug-resistant TB (MDR TB) in 2020, reducing the positive treatment outcomes of the national TB control efforts (Diefenbach-Elstob et al. 2019). A study of MDR-TB in rural Western Province, PNG from 2014 to 2017 found that of the 1548 people registered for TB medications, 1208 (78%) had drug-susceptible TB, and 333 (21.5%) had MDR-TB (Morris et al. 2019). Similarly, a cross-sectional study conducted in four PNG provinces (Madang, Morobe, National Capital District and Western Province) from 2012 to 2014 found that among 1182 TB patients enrolled in the study, 20 new cases (2.7%) and 24 post-treatment cases (19.1%) were diagnosed with MDR-TB (Aia et al. 2016).

In the context of these complex realities, the necessity of effectively implementing TB infection prevention and control (TB-IPC) measures in resource-constrained primary healthcare (PHC) institutions is clear (Bozzani et al. 2022). Although TB transmission is more prevalent outside health facilities, TB infections in PHC settings present a considerable and, in principle, preventable cause of TB incidence. Therefore, designing relevant TB-IPC strategies is essential to prevent TB transmission within PHC settings.

TB-IPC measures have emerged as an effective preventive public health platform to prevent TB transmission in often overcrowded healthcare settings (Reid et al. 2012). Effective TB-IPC measures are critical to the quality of healthcare service delivery to achieve people-centred, integrated, universal health coverage. The WHO TB-IPC guidelines are among the most widely used, and are a mainstay of public health practice to address the prevalence of infectious diseases, such as TB (World Health Organization 2019). These measures are commonly composed of three main pillars: administrative controls – triaging individuals with signs and symptoms of TB, isolating suspected TB cases and initiation of correct medications, developing appropriate health facilities infrastructure to act promptly and appropriately to patients diagnosed with TB in the health facilities; environmental controls – improving the ventilation systems and quality of fresh air in a healthcare setting to minimise TB transmission to health workers; and personal protective control measures – using face masks and respirators appropriately to reduce TB transmission to health workers and individuals seeking medical care in clinical settings. The WHO recommends that healthcare institutions, including PHC facilities that manage TB cases, apply these measures to minimise TB transmission among susceptible individuals in healthcare settings and prevent spread into the wider community.

Despite these crucial recommendations, health system challenges, such as a deficit in basic healthcare infrastructure, insufficient financing of TB-IPC activities and lack of sustained IPC standards, have restricted implementation in resource-constrained PHC in low-income countries (Zwama et al. 2021). Even though TB-IPC measures are suitable for PHC facilities, the extent to which they are effectively implemented is highly dependent on the context of the healthcare system. There is limited understanding of the perceived barriers and strategies of primary health settings and HCWs’ understanding and experience of relevant strategies to address the implementation barriers.

The literature on TB-IPC recommends an increasingly consistent set of strategies for effectively implementing TB-IPC in tertiary healthcare institutions (Zwama et al. 2021). However, there is limited information on strategies related to PHC settings. Zinatsa et al. (2018) provide an excellent overview of some of the strategies relevant to PHC facilities in urban areas of South Africa. These strategies include HCWs training on TB-IPC, improved patient education and awareness of TB-IPC, HCWs as TB-IPC champions, improved social support, and clarity on TB-IPC guidelines. An investigation into PHC settings from a rural area perspective may enhance our understanding of specific strategies required for effective TB-IPC practice (Paleckyte et al. 2021). In some countries, such as PNG, with a high rural population of >85% and a reliance on a distributed PHC system where individuals in need can easily access health care at their location, understanding the key public health policies and prioritised implementation remains under-researched. In PNG, the administration of PHC services was decentralised to the provinces after it gained independence in 1975. The PHC encompassed 1800 aid posts located in the community, 800 health centres and >25 district or rural hospitals. Secondary healthcare services are provided by 23 provincial hospitals and one national referral hospital (Wiltshire et al. 2020). This study aimed to prioritise relevant strategies, and demonstrate their significance in making TB-IPC work better in resource-constrained PHC settings in PNG.

Methods

Study design

A nominal group technique (NGT) was used in this study with HCWs to determine important strategies for TB-IPC practices in rural PHC settings. The NGT is a consensus method used in research focused on problem-solving, idea generation and priority identification (Harvey and Holmes 2012; Chamane et al. 2020). NGT has been regularly used in health services research. For instance, it is used to identify strategies to improve TB-IPC in PHC settings in South Africa (Zinatsa et al. 2018), to explore adolescents’ perspectives on food literacy and its impact on their dietary behaviours in Australia (Ronto et al. 2016), among other things. NGT combines quantitative and qualitative data collection methods and generates data that can be analysed quantitatively and qualitatively (Laenen 2015). The quantitative, nominal group discussion utilised the list of barriers and strategies identified from a survey and semi-structured interviews collected by the lead researcher as part of the PhD research program (Marme et al. 2023). The researcher asked participants to place coloured dots on the strategies they thought were most important for TB-IPC practice. The coloured dots were then counted to determine the most important barriers and strategies.

The qualitative design collected participants’ narratives supporting the selected strategies within the same workshop. The workshop format allowed participants to identify, discuss and agree on key strategies to improve TB-IPC practices in PHC facilities in PNG. The participants were then asked to explain their reasons for selecting the TB-IPC barriers and strategies to build a deeper understanding of HCWs’ perspectives of TB-IPC practice in the PHC system.

Participants and setting

The study population represents the broader HCWs (clinicians and health managers) from PNG national and subnational health services employed in TB programs from the four regions of PNG, including Highlands, Momase, New Guinea Island and the Southern region. A purposive sample (n = 51) (Laenen 2015), HCWs from two-course cohorts attending a Graduate Certificate in Health Science course hosted by another Brisbane-based University, were recruited to participate in the study. Participants’ demographic profiles included years of work experience and health sector level. This comparison was conducted to determine any significant differences between the prioritisation of the strategies. A total of 51 HCWs from two-course cohorts were approached and all agreed to participate. The group was composed of men and women aged between 25 and 44 years.

Data collection procedure

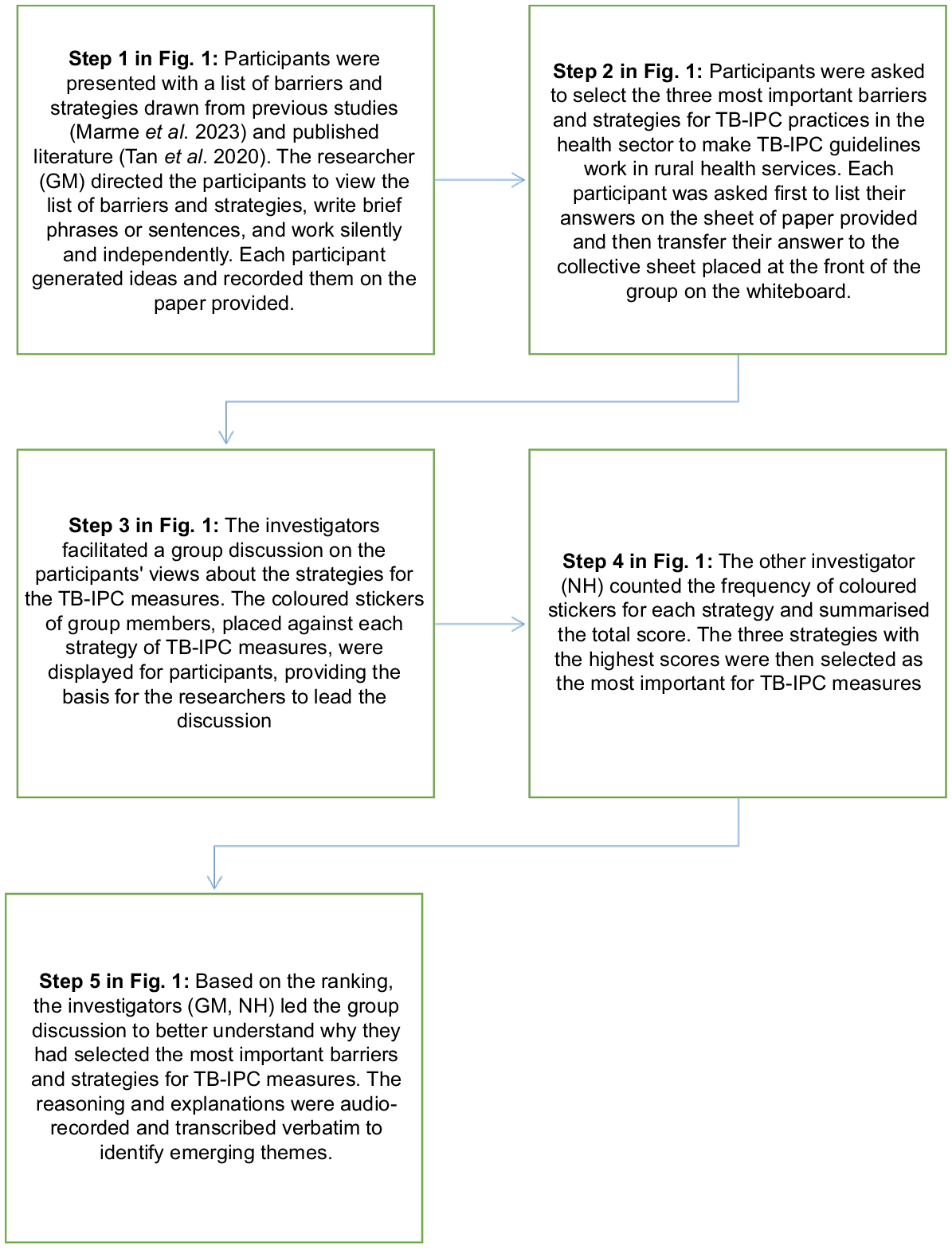

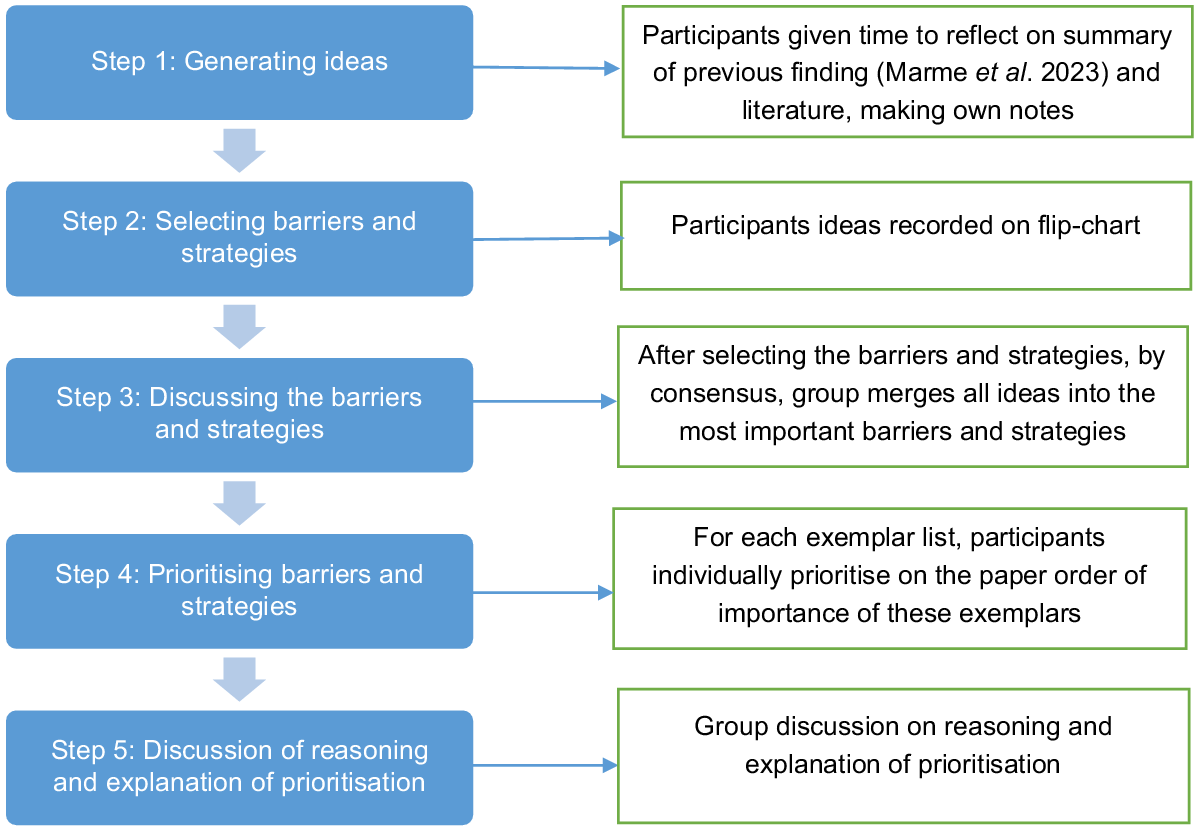

Data were collected between October 2022 and March 2023. The researchers contacted the relevant course lead to seek permission to conduct the group discussion with the participants, and following permission and consent, participants were invited to attend the discussion. After the selection of the most important barriers and strategies using coloured dots, using the NGT (Laenen 2015), experienced HCWs employed in TB-IPC programs were engaged in group discussions to reach a consensus on the selected barriers and strategies to improve TB-IPC measures in rural PHC facilities in PNG. The five stages of the NGT used for this research are summarised in Figs 1 and 2.

The four stages of the nominal group technique used with the inclusion of the fifth step by the authors. Adapted from Ronto et al. (2016).

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) v26 (IBM). First, descriptive statistics, including means and frequencies, were calculated for categorical variables (Onwuegbuzie and Collins 2007). The researcher asked participants to place coloured dots on the strategies they believed were most important for TB-IPC practice. Each participant assigned dots to the strategy they deemed most significant. After collecting the responses, we counted the number of dots assigned to each strategy, providing a raw measure of how frequently each strategy was viewed as important. We analysed their rankings separately, as policymakers and health service providers are independent groups. We summarised the number of dots per strategy for each group and ranked the strategies within each group based on the total dots received. This allowed us to compare how each group prioritised the strategies and whether their rankings differed. We applied the Mann–Whitney U test to determine whether the rankings between policymakers and health service providers were statistically different. This test is beneficial, because it compares two independent groups (policymakers vs health service providers) to check if one group consistently ranks strategies higher or lower. The mean was then calculated to determine any possible differences between each group; for instance, policymakers and health services providers. To calculate the mean rank for each group, we first combine the ranks from policymakers and health service providers. Then, we assign an average rank based on this pooled data. After computing the mean rank for each group, we use the Mann–Whitney U test to evaluate whether the rankings’ differences are statistically significant. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Content analysis was used to analyse the qualitative data. Content analysis is regarded as appropriate for under-researched topics, which often benefit from an in-depth discussion of the entire dataset and for explaining quantitative findings (Laenen 2015). The discussion was professionally transcribed, and one researcher reviewed transcripts for accuracy against the initial audio recordings. The recorded transcripts were read and reread several times to develop familiarisation with the data. One researcher manually coded data using open coding, and using the content analysis technique. The initially assigned codes were condensed into subcategories and categories. The research team met regularly to discuss the codes, subcategories and categories to improve the trustworthiness of the results. The investigators clustered subcategories into categories by the core constructs of the NGT. Supportive quotes from the HCWs were selected to illustrate responses that were common, contrasting or representing a summary of a topic and identified with a participant number.

Results

Participant demographic profiles

In total, 51 respondents participated in the group discussions conducted in October 2022 and March 2023. Respondents were representative of PNG’s four regions (Highlands, Momase, Southern and New Guinea Island). Most were from the Highlands and Momase regions (n = 31, 60%). Most participants were female (n = 34, 67%), and 78% (n = 40) were clinical practitioners employed with TB-IPC programs in healthcare institutions. More than half (n = 26, 51%) were nurses. The demographic characteristics of the study participants are described in Table 1.

| Variables | Total 51 n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 17 (33) | |

| Female | 34 (67) | |

| Age, years, mean ± s.d. | 35 ± 9.3 | |

| Years of work experience | ||

| <10 years | 15 (29) | |

| >10 years | 36 (71) | |

| Regions | ||

| Highlands | 11 (21) | |

| Momase | 20 (39) | |

| Southern | 10 (20) | |

| New Guinea Islands | 10 (20) | |

| Health sector level | ||

| Policy level (policymakers) | 11 (22) | |

| Implementation level (health services providers) | 40 (78) | |

| Educational qualifications | ||

| Masters | 02 (4) | |

| Bachelors | 37 (70) | |

| Diploma/certificates | 14 (26) | |

| Professional cadres | ||

| Doctors | 01 (2) | |

| Health Extension Officers | 14 (27) | |

| Environmental Health Officers | 06 (11) | |

| Nursing Officers | 26 (51) | |

| Other allied health workers (Pathologist) | 06 (11) | |

N, number of participants; s.d., standard deviation; Health Extension Officers are described as professional healthcare providers between physicians and nurses. Often regarded as ‘rural doctors’, Health extension Officers provide comprehensive care and health education, especially in remote locations in PNG.

Generally, HCWs prioritised HCWs’ capacity building on TB-IPC policy and strategy, improvement in healthcare infrastructure, and regular awareness in the community as more important for them to implement TB-IPC guidelines. Table 2 displays HCWs’ recommendations for the most important strategies, with the top three most important by policymakers and health services providers’ groupings highlighted with bolded text. Although HCWs stated that health workers’ capacity building and regular health awareness in the community are most important, these were statistically insignificant, respectively (P = 0.71, P = 0.14). The P-value indicates that policymakers and health service providers regard health workers’ capacity building and health awareness in the community as equally important strategies. This may indicate that applying these strategies will likely improve the TB-IPC program. However, the selection of improvement of healthcare infrastructure was statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05). The reasoning and explanations for these prioritisations will be explored further with illustrative quotes.

| Aspects of TB-IPC strategy | Policymakers (N = 11) M (s.d.) | Health services providers (N = 40) M (s.d.) | P-value | Total (N = 51) M (s.d.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCWs capacity building on TB-IPC policy and strategy | 0.73 (0.47) | 0.56 (0.45) | 0.71 | 0.73 (0.45) | |

| Improvement in health facilities infrastructures | 0.55 (0.52) | 0.58 (0.50) | P ≤ 0.05 | 0.57 (0.50) | |

| Regular awareness in the community | 0.18 (0.40) | 0.33 (0.47) | 0.14 | 0.33 (0.48) | |

| Adequate healthcare resources | 0.76 (0.44) | 0.72 (0.46) | 0.22 | 0.75 (0.50) | |

| Compliance with TB-IPC guidelines | 0.33 (0.47) | 0.28 (0.46) | 0.57 | 0.31 (0.47) | |

| Availability of information, education and technology at the health facilities | 0.18 (0.40) | 0.20 (0.41) | 0.66 | 0.20 (0.40) | |

| Development of TB-IPC policy at the provincial level and communication with facility staff | 0.45 (0.52) | 0.30 (0.46) | 0.10 | 0.33 (0.48) | |

| Adequate support from the district health services | 0.09 (0.30) | 0.05 (0.22) | 0.77 | 0.06 (0.24) | |

| Availability of TB-IPC guidelines at the health facilities | 0.30 (0.40) | 0.20 (0.41) | 0.10 | 0.16 (0.37) |

N, number of participants; M, mean; s.d., standard deviation.

Participants’ perceptions of strategies facilitating HCWs to implement TB-IPC guidelines in PHC settings

Participants ranked HCWs’ capacity building on TB-IPC guidelines and strategy as the first and most important strategy for effectively applying TB-IPC standards in primary healthcare settings out of the nine strategies (Table 2). The ranking shows that policymakers ranked HCWs’ capacity building as the most important strategy (M = 0.73, s.d., 0.47) compared with health service providers (M = 0.56, s.d. = 0.45; P ≤ 0.71; Table 2). Most HCWs agree that upskilling HCWs’ with relevant knowledge of TB and its prevention strategies is crucial for TB control efforts in the country.

A recurrent theme in the discussions was a sense among the participants that HCWs act as health policy translation agents. The participants stated that HCWs require higher-skilled clinical and public health training. Participants expressed that they translate health policies into health services at the PHC level, and that correct training can promote this process. However, participants indicated that the non-availability of relevant guidelines at the PHC facilities prevented them from effectively conducting HCWs training:

Training is most important because we have all these important policies, but who is going to implement them correctly? So, to implement them correctly, we must put the correct training in place, so such policies can be implemented effectively at the PHC settings. But we do not have the document, so how can we conduct training? (Participant, 045)

Most participants highlighted that HCW training promotes relationships, sharing ideas and information, and attaining support in TB control efforts. This, in turn, allows HCWs to learn from peers employed in TB programs in other healthcare settings at the national and subnational levels. The participants proposed that training should be coordinated at the provincial level to minimise the cost:

Training can be organised for HCWs at the provincial level. Get all the health workers to the provincial level, train them and return them to the facilities. Training also provides networking opportunities; they can learn from others in the field. (Participant, 042)

Many participants discussed that training could empower HCWs with the relevant skills and knowledge that would enable them to transform the rural community. This is because HCWs work with patients in the community; therefore, training develops their clinical and public health skills to identify community needs and design appropriate programs to improve their health. HCWs can also provide opportunities and options for individuals to exercise more control over their health and environments, and make choices conducive to health:

HCWs work in the community with patients, so when they are trained with adequate knowledge and information, they can then educate the community. The knowledge does not stop at the facility but continues to the community. (Participant, 023)

Participants viewed strengthening leadership roles in the district health system as essential to sustainable TB training programs. Many participants stated that district TB officers are underutilised and should be empowered with more leadership responsibility, including training needs analysis and conducting training:

At the district level, TB program officers should lead in developing training programs. But they are not always utilised. They must be trained with appropriate skills to conduct training. District training will reduce training costs conducted at the provincial level. (Participant, 015)

The HCWs ranked improving and maintaining the PHC infrastructure as the second most important strategy for effectively applying TB-IPC guidelines in PHC settings. The importance of improving PHC infrastructure as recommended by the HCWs was statistically significant, as both the policymakers (M = 0.55, s.d. = 0.52) and health services providers (M = 0.58, s.d. = 0.50; P ≤ 0.05) ranked improvement and maintenance of PHC infrastructure as the most important aspects (Table 2). A P-value of <0.05 indicates that policymakers and health service providers held divergent views on the importance of enhancing healthcare infrastructure as a critical tactic for implementing TB-IPC guidelines in primary healthcare settings. However, in Table 2, the mean scores for this strategy are quite similar, suggesting that although a statistical difference was identified, the practical significance of this difference may be limited.

The participants discussed that improving and maintaining PHC infrastructure is vital, because it is a key to strengthening access to health services, an equitable and cost-effective approach to accomplishing universal health coverage. It also promotes a resilient healthcare system whereby PHC facilities are better prepared to respond to emergencies, and have the capacity to deal with increasing disease burdens, such as TB and other long-term infections. Furthermore, HCWs explain that health staff should not see their work as fixing problems; instead, they should view PHC infrastructure as helping patients to be healthier. They emphasised that improving PHC infrastructure should promote positive attitudes towards maintaining a healthy lifestyle:

The availability of proper diagnostic facilities, such as laboratory and X-ray, is essential because when patients are admitted with TB, they should feel that these facilities will help them get better. They should not get worried that they have a problem and that health workers will find solutions. (Participant, 022)

Although PHC infrastructure plays a key role in the TB-IPC program, the deficit in basic healthcare infrastructure to effectively implement TB-IPC guidelines was considered a significant impediment:

When we talk about practising infection control in primary health settings in PNG, the infrastructure, such as isolation rooms, TB wards and ventilation systems, is all rundown. They do not meet the recommended standard. (Participant, 032)

Most HCWs discussed that proper healthcare infrastructure is critical, because it acts as a catalyst to deliver comprehensive healthcare to patients. Participants explained that with the availability of a TB ward, for instance, HCWs can provide physical, mental and social care to hospitalised patients. In contrast, participants indicated that inadequate infrastructure makes it difficult for them to deliver comprehensive services in rural health facilities. One participant emphasised this point in conjunction with community health programs:

We cannot travel to villages and conduct health awareness due to resource limitations. Therefore, when patients come to the health facility, we use this opportunity to provide holistic care, but we cannot do enough, because we do not have proper PHC infrastructure. (Participant, 050)

Most participants believed that the risk of spreading airborne infectious diseases could increase because of poor physical healthcare infrastructure, such as TB wards, isolation rooms and ventilation systems in PHC settings. Staff need to be agile and adaptive, mainly because the facilities in rural locations were not designed to ensure HCW safety. The staff must be exceptionally thoughtful in working to prevent themselves and their patients from TB infection, for instance, by promoting fresh air in overcrowded settings and applying masks or respirators during patient interactions:

Poor physical infrastructure increases health workers’ risk of TB infection. Like, you know, health workers work with infectious patients. If the TB ward has a poor ventilation system, health workers are at risk of TB infection. Sometimes, we do not wear face masks, attend to patients and expose ourselves to infection. We should change and wear protective masks. (Participant, 039)

HCWs ranked increasing awareness of TB in the community as the third most important strategy to control TB incidence in PNG. The importance of increasing community awareness and education of TB-IPC varied between policymakers and PHC service delivery staff. Although the difference was not statistically significant, PHC service delivery staff ranked increasing community awareness and education as the most important for them to implement TB-IPC successfully (Table 2).

Participants indicated that because TB prevalence is high in rural communities, health education empowers them with relevant knowledge of TB. Community members can then act as change agents to transform their environment and promote healthy lifestyles. Participants emphasised that providing relevant knowledge of TB can empower individuals, families and communities to be responsible for their health. However, many participants indicated that the lack of awareness of TB makes the community unaware of health risks and increases their vulnerability to TB and other infections:

If health education is conducted regularly in the communities, they will have good knowledge of TB, and organise their life to prevent TB and live a healthy life. Communities with good knowledge of TB can also help others. (Participant, 033)

Discussion

TB-IPC guidelines have emerged as a potential preventive public health strategy to support TB control efforts. However, applying relevant TB-IPC measures to improve TB control efforts in resource-constrained PHC settings is limited and poorly understood. This study explored HCWs’ perspectives on the most important strategies to strengthen the implementation of TB-IPC policy in rural PHC settings in PNG. Despite the diversity in types of workers involved in this study, nearly all participants thought that HCWs capacity building on TB-IPC guidelines, adequate PHC infrastructure and community awareness of TB were the most important strategies for good TB-IPC practices in PHC facilities.

Comprehensive and sustained implementation of TB-IPC guidelines by HCWs is critical to reducing the risk of nosocomial transmission of TB in PHC settings and spreading it into the community. HCWs perceive this as best achieved through training and upskilling HCWs with skills and knowledge of relevant TB-IPC guidelines and standards. This finding aligns with the WHO’s recommendations that promote the significance of healthcare staff training and the practical application of TB-IPC standards (World Health Organization 2019). Although many participants prioritised HCWs’ training as an important strategy for TB-IPC, differences were noted between the responses from policymakers and healthcare providers in the field. Most policymakers (M = 0.73, s.d. = 0.47) tend to prioritise HCWs’ capacity building as the most important strategy compared with health service providers (M = 0.56, s.d. = 0.45; P ≤ 0.71). Although the variations are statistically insignificant, they demonstrate the level of knowledge among the different HCWs and the level of exposure to the TB-IPC guidelines. These findings suggest that HCWs prefer many different priorities and strategies to strengthen the TB burden other than training and skills development for HCWs. This finding aligns with Shrestha et al. (2017), who suggested that the differences in HCWs’ knowledge of TB-IPC guidelines can be addressed through systematic training programs for HCWs. They revealed that HCWs’ knowledge of TB-IPC guidelines was significantly associated with education level and TB training. This implies that periodic in-service training and continuous education can enhance and maintain primary HCWs’ knowledge and skills.

Moreover, Zinatsa et al. (2018) found that a lack of HCWs’ training and conflicting guidelines was responsible for inadequate TB-IPC practices in the South African healthcare system. They maintained that comprehensive training for all HCWs and clarity on TB-IPC guidelines were significant for TB eradication and prevention efforts in South Africa (Zinatsa et al. 2018). Similarly, our study found that key stakeholders perceived the training of HCWs as the highest priority for delivering quality TB care in PHC settings. However, many participants indicated that the lack of capacity building for HCWs, such as training, remains the most significant barrier to effective TB prevention efforts, and contributes to the poor quality of healthcare services in PNG. Participants expressed that the lack of training challenges primary healthcare providers’ abilities to plan and coordinate healthcare services that address the health needs of communities and individuals with chronic health conditions. This further suggests that knowledge can be perceived as a decision-making tool for HCWs to govern their clinical practice, and establish the process through which they are held accountable for continually improving the quality of their health services and safeguarding a high standard of care. Therefore, effective infection control measures, including regular skill-based training and orientation for all categories of HCWs, can improve infection control practices in PHC facilities.

Many HCWs prioritised improving and maintaining PHC setting infrastructure as the second most important strategy for TB-IPC guidelines. The results of this study indicate that most participants were aware of the poor PHC infrastructure in PNG, and how it influences TB care and healthcare services more broadly. This research found minimum differences in the HCWs’ perspectives, indicating that improving healthcare infrastructure, such as diagnostic facilities, TB wards and isolation units, can significantly prevent TB transmission and infection. Most participants concur that periodic maintenance and improvement of PHC facilities are essential to manage diseases, such as TB. This finding is consistent with that of Baumgarten et al. (2018), who indicated that high-quality TB control is associated with some aspects of the primary healthcare infrastructure, including a sound supply system, adequate physical infrastructure and community outreach programs. This is also supported by Luxon (2015), who maintains that infrastructure is a crucial pillar of high-quality healthcare and promotes improved patient care and wellbeing. Therefore, investing in healthcare infrastructure promotes a resilient healthcare system, and ensures that PNG can effectively prevent and respond to current and emerging infectious diseases.

Despite the recommendations that an effective TB-IPC program depends on adequate PHC infrastructure, almost half of the participants expressed concern that a deficit in basic PHC infrastructure remains a severe obstacle to the effective application of TB-IPC guidelines. These findings are consistent with a study in South Africa, which found that poor primary health facility infrastructure coupled with insufficient maintenance, and lack of resources and materials impedes effective TB-IPC implementation in primary healthcare settings (Zinatsa et al. 2018). Similar to our study, HCWs in the South African healthcare system agree that poor infrastructure was one of the most significant obstacles to good TB-IPC practices (Zinatsa et al. 2018). These findings suggest that, as the success of TB control efforts depends on health system factors, health managers and decision-makers need to seriously consider investment in health systems via health systems strengthening interventions, such as healthcare infrastructure, to curb the high TB burden in PNG.

HCWs recommended increasing TB education and awareness programs in rural communities as the third most important strategy for effective TB-IPC practice. Many participants stressed that health awareness educates individuals and communities about health risks and symptoms that may lead to serious health conditions. Jops et al. (2023) argue that decentralising TB care services to the local community can improve TB detection and strengthen public health delivery in PNG. This would mean that the Provincial Health Authorities responsible for primary health services at the subnational levels can ensure a more efficient allocation of healthcare resources, strengthen local resource mobilisation, and improve local governance and accountability (Farmer et al. 2018).

Moreover, the findings in the present study are consistent with the findings of Iribarren et al. (2014), who emphasise that capitalising on community capabilities and maximising established decentralised systems are important, and could mitigate some of the health system barriers preventing accessibility to primary healthcare services. Increasing community health awareness programs would provide opportunities for rural and disadvantaged individuals in PNG to access primary healthcare services in their catchment area, and increase their knowledge of TB, treatment outcomes and risk factors. Increasing primary healthcare services to communities will further reduce the financial burdens on rural inhabitants associated with the excessive travel cost to access TB care at district health centres (Maha et al. 2019; Lewis et al. 2022). The findings in this research have demonstrated that improving the knowledge of the community of TB through health education and health promotion through the decentralisation system was considered an essential strategy to empower individuals, families and communities to take charge of their health.

TB remains a significant public health challenge, particularly affecting economically disadvantaged populations. An essential next step for the national government is to enhance primary healthcare strategies, as detailed in the National Health Plan 2021–2030. This initiative seeks to foster healthier communities by encouraging active participation from local residents. Church health services in Papua New Guinea are pivotal in supporting the government’s primary healthcare initiatives through the Healthy Island Program. Therefore, the government should allocate resources to strengthen church health services, enabling effective implementation of the healthy island concept in local communities.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this study was that it considered the voices of the frontline HCWs engaged in the TB-IPC program to brainstorm ideas and to determine the most important strategies that may work in resource-constrained PHC settings. Although this study has contributed to a better understanding of healthcare experts’ perceptions of the essential strategy for good TB-IPC practice in PHC settings in PNG that could influence policy and practice, the study has some limitations that must be acknowledged. First, HCWs were presented with nine strategies for good TB-IPC practice in PHC institutions. There might be other strategies of TB-IPC measures that should have been included in the present study. However, all researchers conceptualised good TB control practices to identify TB control strategies based on the current literature. Second, HCWs were requested to choose only the three most important TB-IPC strategies that could improve TB-IPC standards in PHC institutions. Third, only one investigator (GM) coded the data, so a potential bias in identifying the codes may exist. To minimise this, the co-authors met regularly to review the codes and categories.

Conclusions

This study aimed to prioritise suitable TB-IPC strategies in PHC settings. The healthcare staff ranked HCWs’ training and education, adequate PHC infrastructure, and increasing community awareness and education as the most important for them to implement TB-IPC guidelines successfully in PHC settings to control the TB burden in PNG. The findings in this study suggest that primary health care enables health systems to strengthen individuals’ health needs, from the promotion of disease prevention to medication and rehabilitation. This approach also ensures that basic healthcare services are delivered in a way that is focused on the community’s needs and respects their health choices. As primary health care is a whole-of-society approach to effectively organise and support the national health system to direct health services closer to communities, the health sector should respond to the national health plan strategy on strengthening primary health systems, including investment in health workforce training, community health services and primary healthcare infrastructure.

Data availability

The data that support this study may be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of funding

The authors thank Griffith University for the PhD scholarships for the first author.

Author contributions

GM, JK, P-A Z, SR and NH conceptualised and designed the study; GM and NH completed the data collection and initial analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data. GM drafted the initial manuscript, and JK, P-A Z, SR and NH substantively revised it. All authors approved the submission of the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Queensland University of Technology, Kelvin Groove campus for allowing the researchers to conduct group discussions with the participants.

References

Aia P, Kal M, Lavu E, John LN, Johnson K, Coulter C, Ershova J, Tosas O, Zignol M, Ahmadova S, Islam TI (2016) The burden of drug-resistant tuberculosis in Papua New Guinea: results of a large population-based survey. PLoS ONE 11(3), e0149806.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Baumgarten A, Hilgert JB, Pinto IC, Zacharias FCM, Bulgarelli AF (2018) Facility infrastructure of primary health services regarding tuberculosis control: a countrywide cross-sectional study. Primary Health Care Research & Development 20(4), e67.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bozzani FM, DIaconu K, Gomez GB, Karat AS, Kielmann K, Grant AD, Vassall A (2022) Using system dynamics modelling to estimate the costs of relaxing health system constraints: a case study of tuberculosis prevention and control interventions in South Africa. Health Policy and Planning 37(3), 369-375.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Chamane N, Kuupiel D, Mashamba-Thompson TP (2020) Stakeholders’ perspectives for the development of a point-of-care diagnostics curriculum in rural primary clinics in South Africa-nominal group technique. Diagnostics 10(4), 195.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Diefenbach-Elstob T, Guernier V, Burgess G, Pelowa D, Dowi R, Gula B, Puri M, Pomat W, Mcbryde E, Plummer D, Rush C, Warner J (2019) Molecular evidence of drug-resistant tuberculosis in the Balimo Region of Papua New Guinea. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Article 4, 33.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Falzon D, Zignol M, Bastard M, Floyd K, Kasaeva T (2023) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the global tuberculosis epidemic. Frontiers in Immunology 14(August), 1234785.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Farmer J, Davis H, Blackberry I, de Cotta T (2018) Assessing the value of rural community health services. Australian Journal of Primary Health 24(3), 221-226.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Harvey N, Holmes CA (2012) Nominal group technique: an effective method for obtaining group consensus. International Journal of Nursing Practice 18(2), 188-194.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Iribarren SJ, Rubinstein F, Discacciati V, Pearce PF (2014) Listening to those at the frontline: patient and healthcare personnel perspectives on tuberculosis treatment barriers and facilitators in high TB burden Regions of Argentina. Tuberculosis Research and Treatment 2014, 1-14.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jops P, Cowan J, Kupul M, Trumb RN, Graham SM, Bauri M, Nindil H, Bell S, Keam T, Majumdar S, Pomat W, Marais B, Marks GB, Kaldor J, Vallely A, Kelly-Hanku A (2023) Beyond patient delay, navigating structural health system barriers to timely care and treatment in a high burden TB setting in Papua New Guinea. Global Public Health 18(1), 2184482.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Laenen FV (2015) Not just another focus group: making the case for the nominal group technique in criminology. Crime Science 4(1), 5.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lewis VJ, MacMillan J, Harris-Roxas B (2022) Defining community health services in Australia: a qualitative exploration. Australian Journal of Primary Health 28(6), 482-489.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Luxon L (2015) Infrastructure – the key to healthcare improvement. Future Hospital Journal 2(1), 4-7.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Maha A, Majumdar SS, Main S, Phillip W, Witari K, Schulz J, du Cros P (2019) The effects of decentralisation of tuberculosis services in the East New Britain Province, Papua New Guinea. Public Health Action 9(1), S43-S49.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Marme G, Kuzma J, Zimmerman P-A, Harris N, Rutherford S (2023) Tuberculosis infection prevention and control in rural Papua New Guinea: an evaluation using the infection prevention and control assessment framework. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control 12(1), 31.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Morris L, Hiasihri S, Chan G, Honjepari A, Tugo O, Taune M, Aia P, Dakulala P, Majumdar SS (2019) The emergency response to multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Daru, Western Province, Papua New Guinea, 2014–2017. Public Health Action 9(1), S4-S11.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Onwuegbuzie AJ, Collins KMT (2007) A typology of mixed methods sampling designs in social science research. The Qualitative Report 12(2), 281-316.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Paleckyte A, Dissanayake O, Mpagama S, Lipman MC, McHugh TD (2021) Reducing the risk of tuberculosis transmission for HCWs in high incidence settings. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control 10(1), 106.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Reid MJA, Saito S, Nash D, Scardigli A, Casalini C, Howard AA (2012) Implementation of tuberculosis infection control measures at HIV care and treatment sites in sub-Saharan Africa. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 16(12), 1605-1612.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Ronto R, Ball L, Pendergast D, Harris N (2016) Adolescents’ perspectives on food literacy and its impact on their dietary behaviours. Appetite 107, 549-557.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Shrestha A, Bhattarai D, Thapa B, Basel P, Wagle RR (2017) Health care workers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices on tuberculosis infection control, Nepal. BMC Infectious Diseases 17(1), 724.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wiltshire C, Watson AHA, Lokinap D, Currie T (2020) Papua New Guinea’s primary health care system: views from the frontline. Available at https://devpolicy.org/publications/reports/PNGs-Primary-Health-Care-System_Wiltshire-Watson-Lokinap-Currie-December-2020.pdf

World Health Organization (2019) WHO guidelines on tuberculosis infection prevention and control, 2019 update. In WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. WHO Press. Available at www.who.int

World Health Organization (2023) Tuberculosis profile: Papua New Guinea 2023. WHO Library Cataloguing. Available at https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/tb_profiles/?_inputs_&tab=%22tables%22&lan=%22EN%22&iso2=%22PG%22&entity_type=%22country%22

Zinatsa F, Engelbrecht M, van Rensburg AJ, Kigozi G (2018) Voices from the frontline: barriers and strategies to improve tuberculosis infection control in primary health care facilities in South Africa. BMC Health Services Research 18(1), 269.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Zwama G, Diaconu K, Voce AS, O’May F, Grant AD, Kielmann K (2021) Health system influences on the implementation of tuberculosis infection prevention and control at health facilities in low-income and middle-income countries: a scoping review. BMJ Global Health 6(5), e004735.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |