‘Back to square one’ – experiences influencing topical corticosteroid use in paediatric atopic dermatitis

Christabel Hoe A , Yasin Shahab A * Phyllis Lau

A , Yasin Shahab A * Phyllis Lau  A

A

A

Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that negatively impacts quality of life. Topical corticosteroids (TCS) remain the first-line management and effective TCS use is associated with improved holistic wellbeing. However, medication self-withdrawal and ‘no-moisture’ method discussions have emerged, and there is evidence that treatment success is influenced by caregivers’ views on TCS use. The aim of this study was to understand the experiences causing parents to deviate from traditional TCS use in paediatric AD management.

A convenience sampling approach was used to recruit caregivers of children with AD, who subsequently participated in one-on-one semi-structured interviews following informed consent. Qualitative data were thematically analysed.

Ten participants were interviewed, of which four were also general practitioners (GPs). The steroid phobia observed among non-healthcare participants was also evident in the views of some GPs. Mismatched expectations within therapeutic relationships lead to some participants seeking alternative therapies and non-medical information sources. Divergence in interpretations of management between primary care practitioners is associated with poor treatment adherence and lowered parent confidence.

A holistic approach to paediatric AD management can effectively support parents and caregivers, as well as reduce treatment burden. Further education for GPs, exploration of psychosocial AD management and alternative therapies may assist in improving patient outcomes.

Keywords: atopic dermatitis, caregivers, interview, medication adherence, paediatrics, parents, phobia, qualitative research, self-management, topical corticosteroid.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic episodic inflammatory skin condition that has a significant negative impact on the quality of life of its sufferers (Alahlafi and Burge 2005). Topical corticosteroids (TCS) remain the first-line management of AD, and improvement in skin conditions have been linked with improvements in social and emotional wellbeing (Lax et al. 2022). In recent years, TCS self-withdrawal has come to the forefront of discussions, often associated with TCS addiction and the ‘no-moisture’ method, which involves the complete withdrawal of TCS and emollient agents, as well as limiting the frequency of showers to assist with natural healing (O’Connor and Murphy 2021). There is evidence that caregivers of children with AD can be influenced by a fear or reluctance to use TCS, or steroid phobia, due to concerns about adverse effects, and thereby impacting treatment adherence (Bos et al. 2019; Albogami et al. 2023). Poor adherence can lead to increased disease burden and an overall diminished quality of life (Smith et al. 2017). In 15 countries, using the validated Topical Corticosteroid Phobia tool, a scale aimed at measuring steroid phobia in adult patients and parents, 33.8% caregivers expressed steroid phobia, citing reasons such as lack of education, complexity of regimens, and poor therapeutic relationships increasing their anxiety surrounding AD and TCS use. Although parental reassurance is a key factor to improving adherence and overall understanding of AD, methods for effective counselling are not well defined (Moret et al. 2013; Smith et al. 2017).

A focus on parental experiences in primary care AD consultations is important, as caregivers largely control the treatment of their children, and overall, this may enhance opportunities for chronic disease management and counselling. The aim of this study was to understand the experiences causing parents to deviate from traditional TCS use in paediatric AD management.

Methods

Research design

A qualitative approach was selected to explore the lived experiences of parents of children with AD through semi-structured, in-depth and open-ended interview questions.

Research team

The research team consisted of CH, YS and PL. CH and YS were both GPs with experience working in Sydney. CH was an academic registrar completing the research component of her training, and she was responsible for the whole research process including report-writing. PL is an experienced researcher in qualitative primary care research. Both PL and YS supervised and mentored CH in the process of methodology, data collection, data analysis and writing.

Research setting

The research was conducted in Greater Sydney, New South Wales (NSW), Australia. As of June 2024, Sydney had a total population of 5,557,200 people, with a large proportion hailing from multiple countries including China, India and Greater Europe. As of 2022, there were 9810 registered and practising GPs in NSW, equating to 12 GPs per 10,000 population. In Australia, patients require a referral from a primary care physician to access specialist dermatology or paediatric services.

Participants and recruitment

Parents of children in Sydney with AD under the age of 16 years were eligible to participate. English-speaking parents were recruited for ease of data collection.

A purposive and convenience sampling approach was used to recruit participants. Invitations were disseminated through QR code flyers placed in general practice clinics, word of mouth or through advertisement in the Central Eastern Sydney Primary Health Network newsletter. Potential participants scanned the code to express interest by providing some basic demographic information (e.g. age, gender, highest level of education obtained, number of children with AD and severity of AD for each child) through a secure Qualtrics online survey. This is to ensure a broad spectrum of participants were recruited to provide broad views and information. Initially, 16 parents expressed interest in participating in the study. A total of 10 participants from this group were interviewed, due to various factors, such as declined interviews. Researcher CH then contacted the participants via email to organise a mutually convenient time for interview.

Data collection

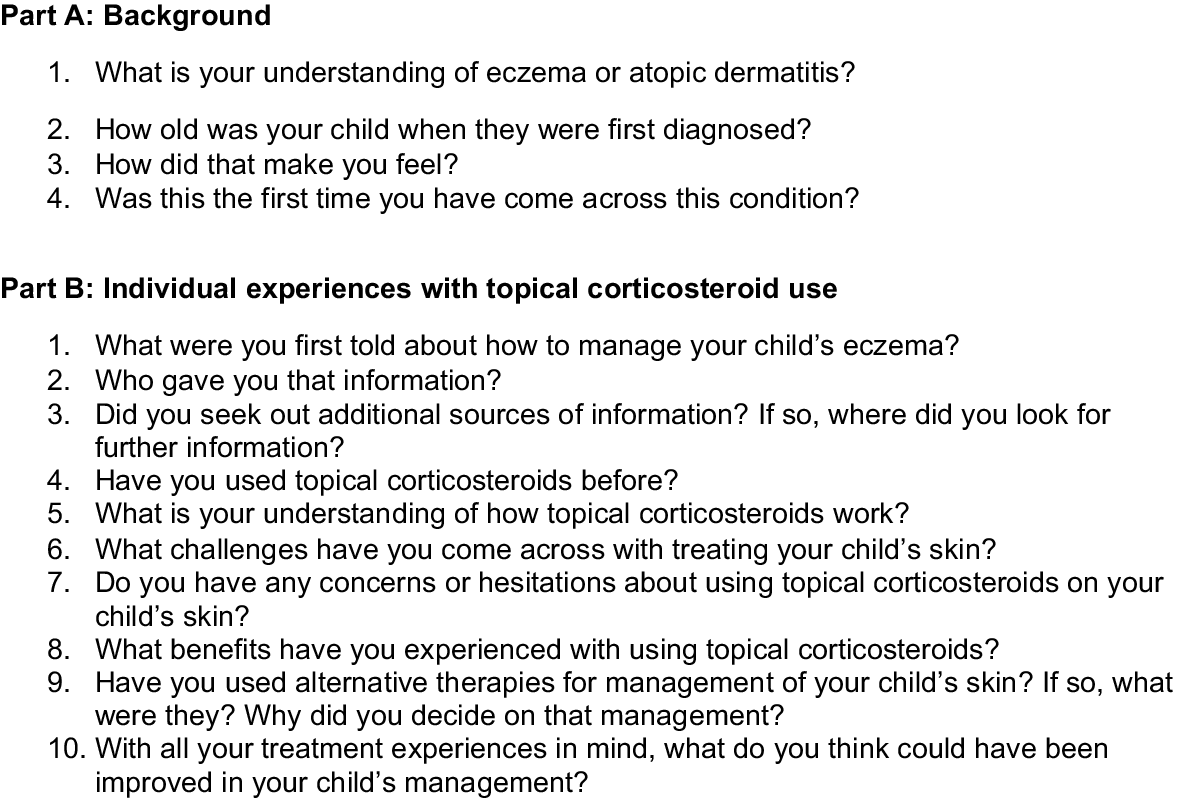

One-on-one, in-depth, semi-structured interviews (Fig. 1) were conducted via telephone by CH. The interview questions were developed based on a review of the literature. The interview questions were piloted to improve fluency and comprehensibility prior to formal interviews with participants. Demographic data and written consent were obtained through a secure Qualtrics online survey via QR code with verbal consent confirmed prior to each interview. Upon completion of the interview, participants were offered a A$30 e-gift card as a token of appreciation.

Interview responses were recorded using a voice recorder and securely stored at Western Sydney University School of Medicine. Interviews were transcribed using a validated external service, and audio recordings were deleted promptly after completion of transcription. Prior to analysis, participants were offered an opportunity to check and edit their responses. Following this, an integrity check of each transcript was undertaken by CH.

Data analysis

NVivo was used to assist in framework thematic analysis using inductive and deductive coding, constant comparison, and recursive refinement, guided by the theory of planned behaviour. The theory of planned behaviour states that a person’s behaviours are shaped by three core components: attitude (personal opinions about the behaviour), subjective norm (perception of others’ opinions in the behaviour) and perceived behavioural control (perception of control over the behaviour; Ajzen 1991).

CH, PL and YS undertook inductive coding of each interview separately. Regular iterative discussions helped to reconcile any differences between the three coders. Emerging common codes were incorporated into the interview protocol in later interviews to enhance data collection. Overarching themes categorised from common codes were compiled in team meetings. Data sufficiency and thematic saturation were determined to have been reached by the research team; that is, when the ‘dataset is comprehensive enough (depth) to both identify recurrent thematic patterns and to account for discrepant examples (breadth)’ (Braun and Clarke 2021; LaDonna et al. 2021).

Results

Demographics

Ten participants were included in our study (Table 1). Participants’ ages ranged between 26 and 55 years, and the majority were women. Most participants had a university education and were employed. Four participants were practising as GPs at the time of their interviews.

| Participant label | Gender | Age range (years) | Education level | Occupation | Age range of children (years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Female | 36–45 | Bachelor | Doctor | 3–8 | |

| B | Male | 26–35 | Masters | Engineer | 0–2 | |

| C | Female | 26–35 | Masters | Doctor | 0–2 | |

| D | Male | 36–45 | Masters | Teacher | 0–2 | |

| E | Female | 26–35 | Bachelor | Analyst | 0–2 | |

| F | Female | 36–45 | Masters | Executive | 3–8 | |

| G | Male | 26–35 | Masters | Doctor | 3–8 | |

| H | Female | 46–55 | Masters | Solicitor | 9–12 | |

| I | Female | 36–45 | Bachelor | Doctor | 0–2 | |

| J | Female | 36–45 | High school equivalent | Carer | 13–16 |

Themes from the interviews

Six broad themes that described influences that shaped behaviours were identified.

Participants sought information from three key resources – themselves, intergenerational experiences (i.e. Interactions with people of different ages) and from other sources, such as health practitioners. Half of the participants personally knew of someone with eczema. Almost all participants sought additional information from health practitioners.

Personal experiences with eczema often influenced participants’ understanding of the condition.

My first personal experience of managing eczema … very steep learning curve. (Participant A, GP)

Participants with intergenerational experiences thought that AD symptoms were dependent on severity and individual circumstances.

They (different types of eczema) are the same condition, but so very different. (Participant B, non-GP)

Experiences (regarding eczema) didn’t carry over at all … totally different in the severity of it. (Participant B, non-GP)

Other participants mentioned that their understanding was limited to communication during GP consultations or from the Internet, and felt it was inadequate.

If I had more education and awareness of the different formulation of the actual corticosteroid or the condition, I would be reassured. (Participant C, GP)

As a result, some participants were unaware of different groups of corticosteroids, such as mineralcorticoids and glucocorticoids. Some identified exogenous androgen hormones as having a similar safety profile to topical glucocorticoids after extrapolating from colloquial terms, such as ‘anabolic steroids’.

I mean … people take them (steroids) to increase muscle mass … just seems unnatural and extreme. (Participant D, non-GP)

Although participants predominantly sought information about eczema from attending consultations with healthcare providers, many also attempted to reinforce their understanding through Internet sources.

I was … doing all this kind of research on the Internet as well. So, I was even thinking to myself … what kind of infection is it? (Participant E, non-GP)

All participants reported attending at least two healthcare visits within the first year of diagnosis. General practitioners appear to be the first point of contact for eczema-related healthcare visits, followed by paediatricians and dermatologists.

Almost half of the participants reported feeling frustrated with the discussions shared during those visits. A few felt that the patient education information from their healthcare providers on the chronicity of AD and treatment did not meet their expectations.

They say try this for a week … but it never goes away. That’s just their answer, you never get quite what you want. (Participant F, non-GP)

Some participants offered suggestions to minimise the mismatch between expectations of healthcare providers and patients, including increasing transparency and better communication.

More transparency on the overall longevity of the condition and long-term strategies on how to manage it, rather than a quick solution. (Participant B, non-GP)

GP participants, despite their knowledge, often had fears of TCS and sought advice from their dermatologist colleagues for management plans for their own children. This often then influenced their own future treatment of their patients.

We saw a paediatrician … in hindsight, I realised, if we started the steroids earlier, it would have been much better. (Participant A, GP)

I’ve seen eczema before. But not firsthand and not a personal experience … well, now I’m not scared at all of the topical steroid. (Participant A, GP)

I didn’t understand as much back then about how to use (TCS) … I was initially, a bit more conservative of my topical steroid use because obviously you’re worried about certain side-effects. (Participant G, GP)

But after talking to many GPs and dermatologists … I’m a lot more aggressive in terms of treating with topical steroids. (Participant G, GP)

All participants recalled challenging experiences associated with eczema management. The majority of these experiences were results of physical complications from poorly controlled eczema.

You don’t want to be scratching every day, every second of your life. (Participant H, non-GP)

He (the child) is just very uncomfortable, you know. You need to be comfortable in your own skin. (Participant H, non-GP)

Some participants commented on the physical appearance of eczema inadvertently caused stigma. A few participants suggested a holistic approach to eczema management, given the impact on mental health.

I had someone describe his skin as reptilian like. (Participant H, non-GP)

He gets embarrassed … the kids point it out you know, what’s wrong with you? That sort of behaviour. It’s hard. (Participant H, non-GP)

Even GP participants who understood the complexities of diagnosing AD were conscience-stricken managing their own children’s skin problems.

Feeling a bit guilty as well … being a first-time parent … we didn’t pick it up for a while. (Participant G, GP)

The chronic and cyclical nature of eczema were a management challenge for many participants. They suggested that treatment is often ineffective and increasingly more frustrating with each flare.

I always feel like we’ve gone back to square one, like all the time. It’s the cycle. (Participant H, non-GP)

A few participants mentioned the financial impact of chronic eczema influenced their management decision-making. Although most participants acknowledged that steroids themselves did not account for a significant portion of their management costs, many recalled spending increasing amounts on other personalised creams or seeing specialists.

If I was going to a dermatologist and then getting the steroids, that would be a A$400 exercise. (Participant F, non-GP)

It is more the custom-made things, but the steroid creams … most of them are used sparingly, so it is not too costly. (Participant I, GP)

Personal knowledge of eczema management based on their experiences played a large role in impacting consistency of TCS use. All participants expressed concerns about the safety profile of steroids, particularly for children.

However, many participants also highlighted the positive features of TCS, which reinforced their continued use. All participants commented on the speed of improvement, and overall improvement of long-term management.

It’s nice to see when you apply it for a few days it (rash) goes away. (Participant F, non-GP)

I know that when it’s well-treated, ah, and treated early that is – it’s pretty manageable. (Participant E, non-GP)

Most participants initially had doubts in their confidence to maintain their child’s AD management. A lack of easily available information was the most stated reason behind their diminished perception of their own abilities. Participants with multiple children with eczema also commented that management became easier over time as they identified effective strategies.

Just a bit more time … and also just the understanding about – developing understanding about, um, using – being, being diligent in the use of topical steroids. (Participant G, GP)

Fragmentation of care was another prominent reason behind their perceived ability to follow their child’s management plan. Many participants commented on receiving different advice from different health professionals, but felt they did not have a proper holistic understanding of eczema management. Some GP participants felt their own knowledge was also lacking regarding identification and treatment of AD.

I didn’t have full understanding of, like, how important it was to – when, at the first sign of eczema, to treat it, um, straight away. (Participant G, GP)

Although some participants felt their own abilities improved after visiting a health professional, the majority felt that solutions were temporary, and their concerns were unheard.

GP doesn’t give you much of an overview. And just when your child is so young, you just think steroids, and then you go, oh, as that’s something really, really strong. (Participant F, non-GP)

Many were not initially aware of the prevalence of paediatric AD in Australia, and felt more reassured by acknowledgement from their GP.

I think it made me a little bit more comforted that she wasn’t the only one suffering from it (eczema). (Participant F, non-GP)

The experiences of friends and family members often acted as deterrents to TCS use.

My girlfriend is a naturopath … she doesn’t agree with steroids … she doesn’t approve. (Participant H, non-GP)

Grandparents … they have heard a lot … how it (steroids) might hinder their growth. (Participant I, GP)

His (a relative) has gone through withdrawal problems (from steroids) and he’s actually got an eye problem like cataract problem. (Participant B, non-GP)

However, a few participants felt that eczema management was individualised, and thought although it was useful to gather information, it did not impact on their approach.

I don’t follow really what his – his own experiences are, ‘cause as I said, everyone’s experiences seem to be different and pretty much unrelated to each other. (Participant B, non-GP)

Some participants expressed frustrations related to inadequate medical management, prompting them to seek alternative treatment advice from friends and families.

I saw online something like bathing the baby using a bit of oatmeal, so that was the therapy I was introduced to as well. (Participant E, non-GP)

I thought dietary as well … I was still breastfeeding … so I’ll try to avoid chilli foods. (Participant A, GP)

In the beginning when we were desperate, we even tried salt rooms. (Participant A, GP)

Participants who had tried alternative therapies, on recommendations from friends and families, did not express a lot of confidence in their effectiveness.

We don’t even know if they (alternative therapies) work or if they are even safe. (Participant J, non-GP)

It is worth noting that the majority of the caregivers interviewed did not pursue alternative treatments of their children’s atopic dermatitis.

Personal interpretation of packaging and labels of the TCS medications often influenced management. All participants recalled instructions calling for sparing use of TCS; however, their definitions of ‘sparing’ varied. Although most participants suggested they strictly followed labels; others felt their interpretation of the severity of the flare played the largest part in applying TCS.

I actually don’t use any sort of measuring system. I just squirt it on my finger and then go around. (Participant F, non-GP)

I would go by the label … only a really thin amount for no more than 2 weeks. (Participant B, non-GP)

Participants often commented on how helpless or frustrated they felt witnessing their child in pain. They felt it was hard to convey their own experiences to others involved in their children’s care, including grandparents and childcare staff. Some participants felt that although management plans made it easy to share with other carers, the consistency of management could not be guaranteed.

She’s in childcare, um, I can’t really keep an eye on what she’s doing to make sure that like, she’s not going to scratch herself to death. (Participant B, non-GP)

Whereas at home I can kind of be there, I don’t know, that’s kind of where (childcare) the stress kind of stems from. (Participant B, non-GP)

Discussion

The aim of this research was to understand the experiences causing parents to deviate from recommended TCS use in paediatric AD management. Through the process of this qualitative study, we have identified several key themes that impact on caregiver management of eczema for their children.

Adherence to treatment regimens continues to play a significant role in the overall improvement in a child’s AD. There is much evidence in the literature on negative experiences with healthcare professionals and patient flares underpinning the perpetuation of steroid phobia and associated non-adherence (Kojima et al. 2013; Curry et al. 2019; Gomes et al. 2022). Our results supported these findings, particularly substantiating that healthcare advice was often unclear and uncoordinated, leading to decreased levels of confidence in subsequent treatment plans.

Inadequate information from healthcare providers also often leads to parents seeking information from friends and families, as well as media sources, frequently leading to misinformation about TCS potency and alternative therapies (Charman et al. 2000; Teasdale et al. 2021). Whereas some of our participants felt that although non-healthcare sources of information were initially helpful, they did not ultimately impact on their own treatment plans.

Our results show that concerns of TCS side-effects, such as cataracts and skin atrophy, continue to perpetuate poor adherence with AD treatment. This is despite complications of poorly controlled eczema, including growth impairment and dyspigmentation, mimicking some of the known side-effects of long-term TCS use (Li et al. 2018). Alternative therapies, including herbal medications, salt rooms, naturopathic treatments and allergy testing, are often seen as a last hope option for many families, and result in difficulty reconciling advice from health professionals to information from other sources (Powell et al. 2018; Tan et al. 2022). The majority of our participants did not, however, pursue alternative treatments, and the discussions around alternative therapies tended to be associated with food allergies and subsequent dietary changes, similar to the findings in other studies (Hon et al. 2018; Powell et al. 2018; Tan et al. 2022). Despite the predominance of parents deeming ‘natural’ treatments to be akin to ‘safe’, some have doubts, because the safety profile and effectiveness of many alternative treatments are mostly unknown (Tan et al. 2022)

Our results show that challenges arising from AD management are multifactorial and may impact on larger psychosocial concerns, such as long-term mental health. issues. Further discussions surrounding the psychosocial impact of AD should be undertaken with patients and caregivers in primary care, to provide reassurance and assist with identifying optimal treatments, as well as debunking misinformation to allow for the best possible outcomes for paediatric patients with AD (Magin et al. 2009).

Despite participants seeking help from primary care practitioners on multiple occasions within the first year of diagnosis, fragmentation in care inherent in our health system prevented appropriate education for patients and caregivers, and impacted subsequent treatment adherence. Inherent factors causing fragmentation of care, such as funding silos, complex healthcare policies and overall difficulty navigating or securing appointments with multiple healthcare practitioners, eventually overburdens patients’ ability to receive timely and effective chronic care management. A parent’s initial interpretation of treatment plans, such as their understanding of TCS medication labels or patient safety leaflets, often impacts the caregiver’s perceived burden of treatment and openness to return to their healthcare practitioner for further discussions (Gore et al. 2005). Parents often are looking for a permanent ‘cure’ to AD, with the cyclical nature of eczema not clearly discussed in initial consultations (Hon et al. 2015). This highlights the divergent interpretations of AD and associated treatment, with GPs focusing on the biomedical approach, and parents preferring a more holistic approach, including the psychosocial impact of eczema (Powell et al. 2018).

The lack of control in management of their children’s AD, including the perception that preschool staff and other caregivers are not able to provide adequate individualised care, appears to increase the burden of complex AD treatment on families. Longer supervision of treatment by healthcare providers has previously been correlated with a lower prevalence of steroid phobia, and may increase parental confidence levels and subsequent TCS adherence for improved AD outcomes (Tangthanapalakul et al. 2023).

This study was rigorously conducted and evaluated using a framework thematic analysis approach guided by the theory of planned behaviour. It provides a rich in depth exploration of the caregivers’ experiences, allowing for a holistic understanding and flexibility in data collection. Interviews were taken through videoconferencing services, limiting our ability to extrapolate data from non-verbal cues. The semi-structured interviews were initially undertaken with reference to our created interview guide, which may have inherently allowed for leading questions and reinforcing the interviewer’s confirmation bias. Whilst a convenience sampling approach was used, the majority of our participants had a high level of education, which makes it difficult to extrapolate the results to fit alternative populations in Australia. Although the sample size was small, data sufficiency and thematic saturation had been reached.

Improving outcomes for paediatric patients with AD at the primary care level relies on a combination of parental understanding of the condition and management alongside appropriate holistic patient education from their trusted healthcare professionals. Steroid phobia is widespread, and patients and caregivers need further education in medication safety in primary care. Fragmentation of care in the healthcare system continually leads to confusion in advice provided by healthcare providers and dissatisfaction in AD management. Our study reinforces the need for clear and transparent discussions in the primary care setting to develop understanding of AD, build patient trust, and improve overall usage of TCS safety and management plans. Strategies to help facilitate this may include further education for GPs, as well as public health promotions, such as practice-based interventions, to ensure effective management of paediatric AD. Further research into the psychosocial impact of AD should also be considered in the future.

Data availability

The data that support this study cannot be publicly shared due to ethical or privacy reasons and may be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author if appropriate.

Declaration of funding

This research received funding from the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners.

Acknowledgements

We thank our participants for their time, and Central Eastern Sydney PHN for assisting with recruitment.

References

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50(2), 179-211.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Alahlafi A, Burge S (2005) What should undergraduate medical students know about psoriasis? Involving patients in curriculum development: modified Delphi technique. BMJ 330(7492), 633-636.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Albogami MF, Aljomaie MS, Almarri SS, Al-Malki S, Tamur S, Aljaid M, Khayat A, Alzahrani A (2023) Topical corticosteroid phobia among parents of children with atopic dermatitis (Eczema)- a cross-sectional study. Patient Preference and Adherence 17, 2761-2772.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bos B, Antonescu I, Osinga H, Veenje S, De Jong K, De Vries TW (2019) Corticosteroid phobia (corticophobia) in parents of young children with atopic dermatitis and their health care providers. Pediatric Dermatology 36(1), 100-104.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Braun V, Clarke V (2021) To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 13(2), 201-216.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Charman CR, Morris AD, Williams HC (2000) Topical corticosteroid phobia in patients with atopic eczema. British Journal of Dermatology 142(5), 931-936.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Curry ZA, Johnson MC, Unrue EL, Feldman SR (2019) Caregiver willingness to treat atopic dermatitis is not much improved by anchoring. Journal of Dermatological Treatment 30(5), 471-474.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gomes TF, Kieselova K, Guiote V, Henrique M, Santiago F (2022) A low level of health literacy is a predictor of corticophobia in atopic dermatitis. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia 97(6), 704-709.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Gore C, Johnson RJ, Caress AL, et al. (2005) The information needs and preferred roles in treatment decision-making of parents caring for infants with atopic dermatitis: a qualitative study. Allergy 60(7), 938-943.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hon KL, Tsang YCK, Pong NH, et al. (2015) Correlations among steroid fear, acceptability, usage frequency, quality of life and disease severity in childhood eczema. Journal of Dermatological Treatment 26(5), 418-425.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hon KL, Leong KF, Leung T, et al. (2018) Dismissing the fallacies of childhood eczema management: case scenarios and an overview of best practices. Drugs in Context 7(2), 212547.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kojima R, Fujiwara T, Matsuda A, et al. (2013) Factors associated with steroid phobia in caregivers of children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatric Dermatology 30(1), 29-35.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

LaDonna KA, Artino AR, Jr, Balmer DF (2021) Beyond the guise of saturation: rigor and qualitative interview data. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 13(5), 607-611.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Lax SJ, Harvey J, Axon E, et al. (2022) Strategies for using topical corticosteroids in children and adults with eczema. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3(3), CD013356.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Li Y, Han T, Li W, Li Y, Guo X, Zheng L (2018) Awareness of and phobias about topical corticosteroids in parents of infants with eczema in Hangzhou, China. Pediatric Dermatology 35(4), 463-467.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Magin PJ, Adams J, Heading GS, et al. (2009) Patients with skin disease and their relationships with their doctors: a qualitative study of patients with acne, psoriasis and eczema. Medical Journal of Australia 190(2), 62-64.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Moret L, Anthoine E, Aubert-Wastiaux H, Le Rhun A, Leux C, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, Stalder JF, Barbarot S (2013) TOPICOP©: a new scale evaluating topical corticosteroid phobia among atopic dermatitis outpatients and their parents. PLoS ONE 8(10), e76493.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

O’Connor C, Murphy M (2021) Scratching the surface: a review of online misinformation and conspiracy theories in atopic dermatitis. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology 46(8), 1545-1547.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Powell K, Le Roux E, Banks J, et al. (2018) GP and parent dissonance about the assessment and treatment of childhood eczema in primary care: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 8, e019633.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Smith SD, Harris V, Lee A, Blaszczynski A, Fischer G (2017) General practitioners knowledge about use of topical corticosteroids in paediatric atopic dermatitis in Australia. Australian Family Physician 46(5), 335-340.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

Tan S, Phan P, Law JY, Choi E, Chandran NS (2022) Qualitative analysis of topical corticosteroid concerns, topical steroid addiction and withdrawal in dermatological patients. BMJ Open 12(3), e060867.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tangthanapalakul A, Chantawarangul K, Wananukul S, et al. (2023) Topical corticosteroid phobia in adolescents with eczema and caregivers of children and adolescents with eczema: a cross-sectional survey. Pediatric Dermatology 40(1), 135-138.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Teasdale E, Muller I, Sivyer K, et al. (2021) Views and experiences of managing eczema: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. British Journal of Dermatology 184(4), 627-637.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |