Barriers and facilitators to accessing sexual health services among middle-aged and older adults in the UK, including those with disabilities: a qualitative analysis

Charlotte Letley A , Isabella Kritzer B , Yoshiko Sakuma A , Hayley Conyers A , Sophia Randazzo B , Jason J. Ong A C , Suzanne Day B , Dan Wu

A C , Suzanne Day B , Dan Wu  A D , Fern Terris-Prestholt

A D , Fern Terris-Prestholt  E , Joseph D. Tucker

E , Joseph D. Tucker  A B and Eneyi E. Kpokiri

A B and Eneyi E. Kpokiri  B *

B *

A

B

C

D

E

Abstract

Middle-aged and older adults have unmet sexual health needs but often encounter challenges in accessing sexual health services (SHS). Individual, social, and environmental issues discourage middle-aged and older adults from accessing SHS. This study aimed to examine the barriers and facilitators experienced by middle-aged and older adults when accessing SHS in the UK. We included disabled people and sexual minorities with intersectional needs.

We organised semi-structured interviews with residents in England aged 45 years and older, including disabled people and sexual minorities. Participants were recruited using social media, primary care clinics, and community-based organisations. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Levesque et al.’s framework of healthcare access was used as a theoretical guide for analysing and presenting the study findings. After initial coding and theme generation, sub-themes of barriers and facilitators were mapped onto the healthcare access framework.

The mean age of the 22 participants was 59 years with 15 men and 7 women. Participants included people of different ethnicities (White British, Black African, and White mixed), disabilities, and sexualities. These participants highlighted various barriers to accessing SHS. Physical obstacles, such as narrow corridors, were cited as significant hindrances, although accommodations, such as physical assistance, were noted to enhance accessibility. Additionally, participants noted the pervasive stigma surrounding sexual health in older adults, exacerbated by healthcare providers presuming asexuality within this demographic. To address these multi-faceted challenges, greater involvement of disabled older individuals in the design of SHS is advocated. This collaborative approach is believed to expedite the development of age-responsive clinical services, fostering inclusivity and accessibility while simultaneously addressing psychological and social barriers.

Our data suggest that physical inaccessibility and stigma are persistent barriers to accessing SHS for older disabled people. Increasing training for healthcare providers, further research, and supportive policies are needed to improve delivery and access to SHS for older adults, including those with disabilities in the UK.

Keywords: barriers, disabilities, England, facilitators, older adults, qualitative analysis, sexual health, United Kingdom.

Background

Many sexual health research studies focus on youth and exclude older populations.1 However, the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing revealed 77.7% of men and 53.7% of women aged over 50 years remain sexually active.2 Research indicates higher rates of sexual dysfunction among older adults in England, with approximately half experiencing low sexual function, distress about sex, or increased risk of STIs.3 Older adults are also more prone to chronic illness, disability, or comorbidities than younger adults.4–7 Additionally, HIV prevalence globally among those aged 50 years and older has doubled in the past decade and continues to rise.8

Demographers estimate the number of people over the age of 60 years will double by 2050.9 The World Health Organization (WHO) defines sexual health as a fundamental human right,10 yet access to basic sexual health services (SHS) remains poor for most middle-aged and older adults. Those with intersectional needs, such as those from ethnic, sexual, or disability minority groups, experience greater problems accessing services.11 Barriers for these sub-groups include internalised stigma, ageist and ableist discrimination from health professionals, and challenges in the socio-physical environment, including physical inaccessibility.1,11–13

Research into the sexual health needs of middle-aged and older adults in the UK is limited. Current research suggests barriers to access include misconceptions about the relevance of sexual health issues in older adults,8 stigma from healthcare providers (HCP) leading to embarrassment, and a lack of sexual health discussions initiated by HCPs.14 Although some studies have explored access barriers, such as Gott et al.’s research in 2003,15 the applicability of these findings to the current landscape is limited due to political and structural changes, such as the implementation of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 (UK).16 These studies also lack exploration of service-based and structural access determinants.

An aging population increases the importance of developing high-quality and accessible SHS for older adults.9,17 To enact practice changes and enhance access, additional research is imperative to thoroughly investigate the diverse and intersectional factors influencing SHS access in this demographic group. This qualitative study describes the barriers and facilitators of accessing SHS among middle-aged and older adults in the UK.

Methods

This study is part of the Sexual Health in Older Adults Research (SHOAR) study at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). The SHOAR study employed a mixed-methods, community-engaged approach, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative components to identify factors influencing sexual health service preferences among older adults aged 45 years and older in the UK. For this analysis, we conducted a secondary qualitative analysis using data from 22 semi-structured interviews conducted between October 2021 and July 2022.

Participant recruitment

Eligible participants were adults aged 45 years and older residing in the UK for a minimum of 6 months. Convenience sampling and snowball techniques were used to recruit participants. Study information was distributed to general practitioner offices in London, community-based organisations, care homes, and SHS. Recruitment efforts included posting study information on social media platforms (Facebook, X, Nextdoor) and through personal networks of older adults. Purposive sampling was employed to recruit disabled adults through Independent Living Alternatives, an organisation that engages older and disabled adults in the London community. Participants were offered a £30 gift card as an incentive to participate.

Data collection

Eighteen interviews were conducted by an experienced qualitative researcher (EEK), and four interviews were conducted by a trained master’s student. Interviews took place via phone calls and Zoom teleconference, lasting approximately 1 h each. An interview topic guide (see Supplementary material file S1) was piloted with the first two participants, with minor edits made thereafter. Prior to interviewing, participants were provided with an information leaflet and consent forms. The interview process began with restating study information and obtaining verbal consent for recording discussion sessions. This was followed by demographic questions covering age, ethnicity, sexuality, location, relationship status, and disability status. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. To ensure appropriateness for participants living with disabilities, the questions and language were reviewed by a senior disability researcher (TS) and the director of Independent Living Alternatives (TJ).

Theoretical framework

We utilised Levesque et al.’s modern healthcare access framework18 to assess access to health care.19 This framework adopts a holistic perspective, encompassing individual and service-based factors, with each dimension represented by five key components: (1) approachability, (2) acceptability, (3) availability, (4) affordability, and (5) appropriateness.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis, following Braun and Clarke’s method,20 was employed to identify patterns in the interview data. An inductive approach was initially used to derive codes from the data without predetermined codes or themes. Subsequently, a deductive approach was utilised to examine codes and themes for alignment with Levesque’s framework. Data analysis was facilitated using Microsoft Excel and a data extraction table to map out themes. These sub-themes were then merged to form broader themes representing overarching patterns. Codes lacking sufficient data were considered inconclusive. To visualise the connections and variations among codes, sub-themes, and themes, a theme map was utilised. One coder (CL) generated initial codes and sub-themes to Levesque’s framework. All coding was reviewed by a second researcher (EEK).

Results

A total of 22 participants (15 males, 7 females) aged 45–54 years (27.3%), 55–64 years (45.5%), and over 65 years (22.7%) were interviewed (Table 1). The majority identified as heterosexual (63.6%), with others identifying as gay (31.8%) and bisexual (4.5%). In terms of relationship status, 45.5% were married, 45.5% single, and 9.1% in a long-term relationship. Ethnically, 63.6% were White British, 22.7% Black African, 4.5% Black British, 4.5% White Greek, and 4.5% Black Afro-Caribbean. Most resided in London (68.2%), while others were in Hertfordshire (13.6%), the Southeast (9.1%), the Northwest (4.5%), and the Northeast (4.5%). Nine participants reported a disability (40.9%), with all reported as physical disabilities. This study identified six primary barriers and seven facilitators relevant to accessing SHS. Detailed themes and sub-themes are available in Supplementary Table S1.

| Variable | Participants n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 45–54 | 7 (31.8) | |

| 55–64 | 10 (45.5) | |

| 65+ | 5 (22.7) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 15 (68.2) | |

| Female | 7 (31.8) | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White British | 14 (63.6) | |

| Black African | 5 (22.7) | |

| Black British | 1 (4.5) | |

| Black Afro-Caribbean | 1 (4.5) | |

| White Greek | 1 (4.5) | |

| Sexuality | ||

| Heterosexual | 14 (63.6) | |

| Homosexual | 7 (31.8) | |

| Bisexual | 1 (4.5) | |

| Resident location | ||

| London | 15 (68.2) | |

| Hertfordshire | 3 (13.6) | |

| Southeast | 2 (9.1) | |

| Northeast | 1 (4.5) | |

| Northwest | 1 (4.5) | |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married | 10 (45.5) | |

| Single | 10 (45.5) | |

| Long-term relationship | 2 (9.1) | |

| Presence of a disability | ||

| Yes | 9 (40.9) | |

| No | 15 (59.1) | |

Barriers accessing SHS

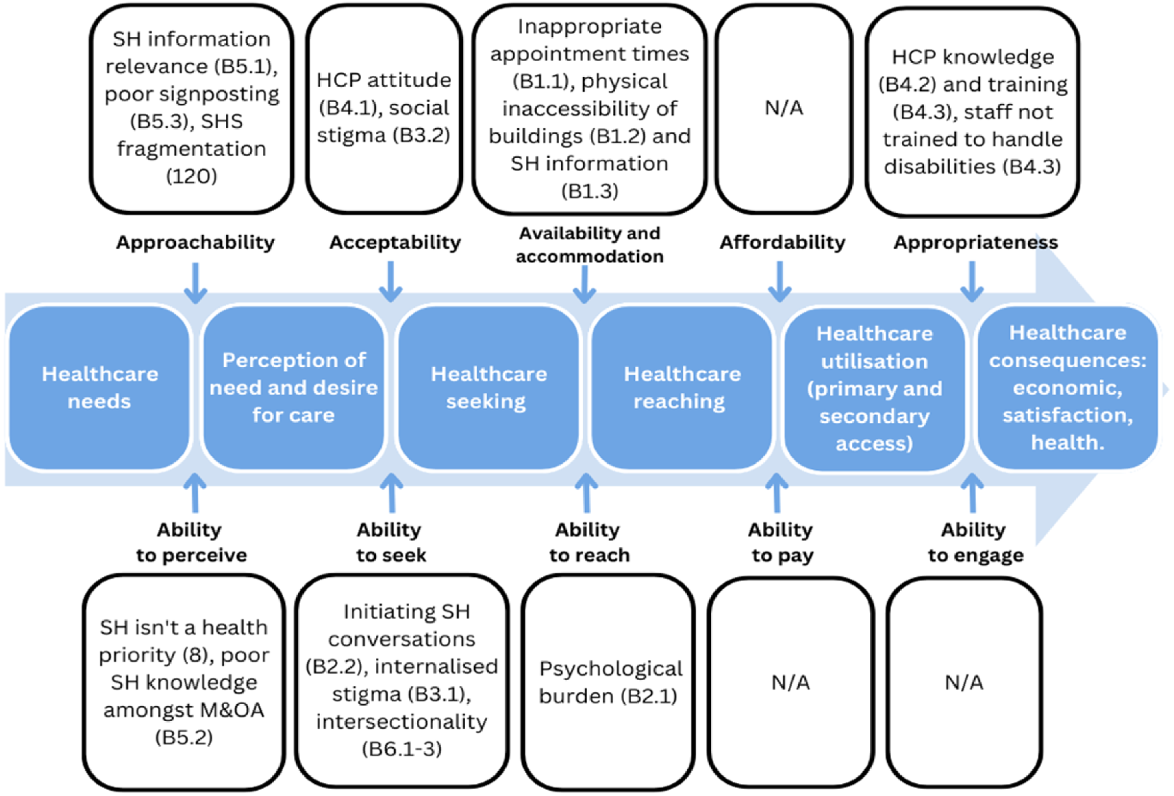

Several participants emphasised barriers to accessing SHS, pointing to physical inaccessibility, stigma, and HCP attitudes as primary challenges; these are theoretically mapped in Fig. 1.

Applied Levesque’s framework: barriers to accessing SHS. A diagram demonstrating how the sub-themes of barriers to access were mapped onto Levesque’s framework. M&OA, middle-aged and older adults; SH, sexual health.

Physical inaccessibility significantly hampered utilisation of SHS, encompassing factors related to service availability and accommodation.3 Challenges frequently cited by participants revolved around the physical accessibility of buildings for adults with disabilities. These challenges included inadequate lift facilities, narrow corridors causing wheelchair inaccessibility, small waiting rooms, inaccessible toilets, and unsuitable examination beds and equipment. Participants described such environments as unwelcoming to adults with disabilities. They emphasised that physical inaccessibility often resulted in missed examinations, procedures, and treatments, leading to exacerbated morbidity and discouraging future treatment-seeking behaviours.

I had to turn away treatment because I couldn’t get on the bed.…It just made me really feel like I am a second-class dispensable citizen. (Participant 20; age 54 years, Disabled)

Many participants observed poor sexual health service signposting and lack of tailored sexual health information. Participants also expressed confusion regarding sexual health service locations, how to obtain sexual health information, and which HCP to approach with sexual health issues. Additionally, some participants noted that public sexual health information and advertising often lacks relevance to the specific needs of middle-aged, older, or disabled adults. This contributed to feelings of alienation and limited access.

Negative HCP attitudes and social stigma represent significant barriers to individuals seeking and accepting SHS.14,21 Several participants reported experiencing stigmatising attitudes from HCPs regarding sexual health, describing feelings of being judged or dismissed. For example, Participant 18 described being dismissed by an HCP based on age and disability, highlighting the detrimental impact on their sexual health.

People have actually said to me, didn’t they ask, you know, certain [SH] questions?... And I realised that obviously the person doing it just skipped over the form, you know, they’ve literally just missed a page … They just made an assumption … Which is, you know, based on age and everything else. (Participant 19; age 62 years, Non-disabled)

Social stigma significantly impacts an individual’s perceived acceptability of seeking SHS. Assumptions of asexuality based on older age and disability were reported.

Participants highlighted the inaccessibility of online SHS due to issues with information formatting, design, and physical requirements for use, such as typing with sufficient dexterity. Additionally, some older disabled adults described facing barriers accessing sexual health information privately, especially those with personal assistants who may lack the necessary privacy to feel comfortable discussing sexual health issues.

HCP knowledge and training are crucial aspects related to the suitability of services for clients, including both technical expertise and interpersonal skills involved in service delivery.18 Participants highlighted shortcomings in HCPs’ understanding of the sexual health needs of middle-aged and older adults (Table S1), with many noting instances where HCPs were unable to address their specific sexual health concerns.

I’ve been able to ask all the questions, I haven’t got any of the answers though. (Participant 5, age 68 years. Non-disabled)

Furthermore, some participants reported that HCPs assumed they were sexually inactive based on their age or disability status, indicating a lack of awareness and understanding of sexual health needs in this demographic.

I even had one GP say to me when they came round and said, ‘Oh, I don’t need to talk about contraception with you because you are not having sex’. (Participant 18; age 68 years, Disabled)

To further this, multiple participants reported staff in SHS lacked the necessary training to accommodate individuals with disabilities. Participant 22 emphasised that staff were unaware of their legal obligation to provide assistance, leading to embarrassment for individuals.

Facilitators for accessing SHS

The facilitators identified are mapped theoretically in Fig. 2. Improving physical accessibility, a key aspect of enhancing service availability and accommodation, emerged as a significant facilitator for accessing SHS.18 Participants recommended various changes, such as installing more hoists, providing Changing Places Toilets (a fully accessible toilet with a height adjustable changing bench, a hoisting system, a peninsular toilet, and enough space for the disabled person with their wheelchair and two carers), widening corridors and doors, ensuring spacious waiting areas, implementing lift or ramp access, monitoring lift use, offering accessible parking, and facilitating sexual health home visits for those unable to access clinics. Additionally, there was a call to improve the accessibility of sexual health information for individuals with sensory impairments and physical disabilities. Many participants stressed the importance of enhancing existing services rather than segregating disabled adults into specialist centres.

I think it’s outrageous to send disabled people to different places. Services should be upscaled in terms of supporting disabled people to access services, and that should be for everybody. (Participant 22; age 61 years, Disabled)

Applied Levesque’s framework: facilitators to accessing SHS. A diagram demonstrating how sub-themes of facilitators to access to were mapped onto Levesque’s framework. M&OA, middle-aged and older adults; SH, sexual health.

The perceived segregation was seen as a form of societal exclusion. Participants proposed involving disabled adults in the design of SHS and equipment to enhance accessibility. They also highlighted the need for improved monitoring to ensure compliance with legislative access requirements, such as conducting regular access audits. Moreover, there was a consensus on the necessity for enhanced staff disability awareness training to better serve individuals with disabilities.

Improving approachability involves making individuals aware of available services, their benefits, and how to access them.18 Participants recommended directing older adults to SHS through targeted signposting and suggested including images of older and disabled adults in sexual health information to enhance relatability.

When there’s leaflets and posters and information, it’d be great to have images of disabled people and to celebrate disabled people as sexual beings. And so that when we see a poster, we say, oh yeah, that’s about me as well or that includes me. (Participant 17; age 71 years, Non-disabled)

Creating culturally appropriate sexual health information for ethnic minority groups was identified as a strategy to empower these communities to access SHS. Additionally, leveraging organisations or networks that engage with older and disabled adults, along with targeted public advertising of SHS, were suggested as methods to disseminate sexual health information to these demographics.

Enhancing the acceptability of SHS among middle-aged and older adults requires improving the perceived appropriateness of seeking such services.18 This includes positive and distigmatising HCP attitudes towards older adults seeking SHS. Clear advertising indicating that sexual health discussions are welcome and encouraged, through signs or leaflets, was also suggested. Additionally, the instigation of sexual health discussions by HCPs was highlighted as a facilitator by many participants. Initiating sexual health discussions during consultations can help alleviate pressure or embarrassment felt by patients, normalising such discussions. Similarly, it was reported that SHS should openly welcome LGBTQ individuals

I’m from a generation where we got quite a lot of hostility from even some sexual health clinics, so I would say my perception of them as being gay friendly would be very important. (Participant 15; age 57 years, Non-disabled)

Patient perceptions of current SHS are influenced by historical oppression, suggesting a need to promote the acceptability of all sexualities, genders, abilities, and ethnicities. Combatting this may involve clearly promoting inclusivity and acceptance within SHS. Additionally, changing societal views towards sexual health in middle-aged and older adults was frequently mentioned as a facilitator. Normalising sexual activity in middle-aged and older adults could help reduce internalised stigma around seeking SHS and empower access.

Improving the appropriateness of SHS requires enhancing both technical proficiency and interpersonal skills among HCPs.22–24 Participants stressed the necessity for HCPs to adopt more nuanced and individualised approaches to sexual health from training that adequately addresses the diverse sexual health needs of middle-aged and older adults, moving beyond a standardised approach. Participant 19 highlighted that the current ‘tick-box’ approach fails to address all intersectional needs.

That’s really lacking in sexual health, when you’ve got a disability and sexual health, to be able to go to somebody who can unpick the things of what is your impairment and what is happening with your sexual health and how it might be interacting. (Participant 18; age 68 years, Disabled)

They emphasised the importance of a more holistic and individualised approaches that consider intersectional needs. Suggestions included training HCPs on how to engage with patients who have personal assistants and ensuring discussions are culturally and personally relevant. Additionally, participants highlighted the significance of creating a safe and confidential environment within SHS to encourage open dialogue and address patients’ concerns effectively.

Discussion

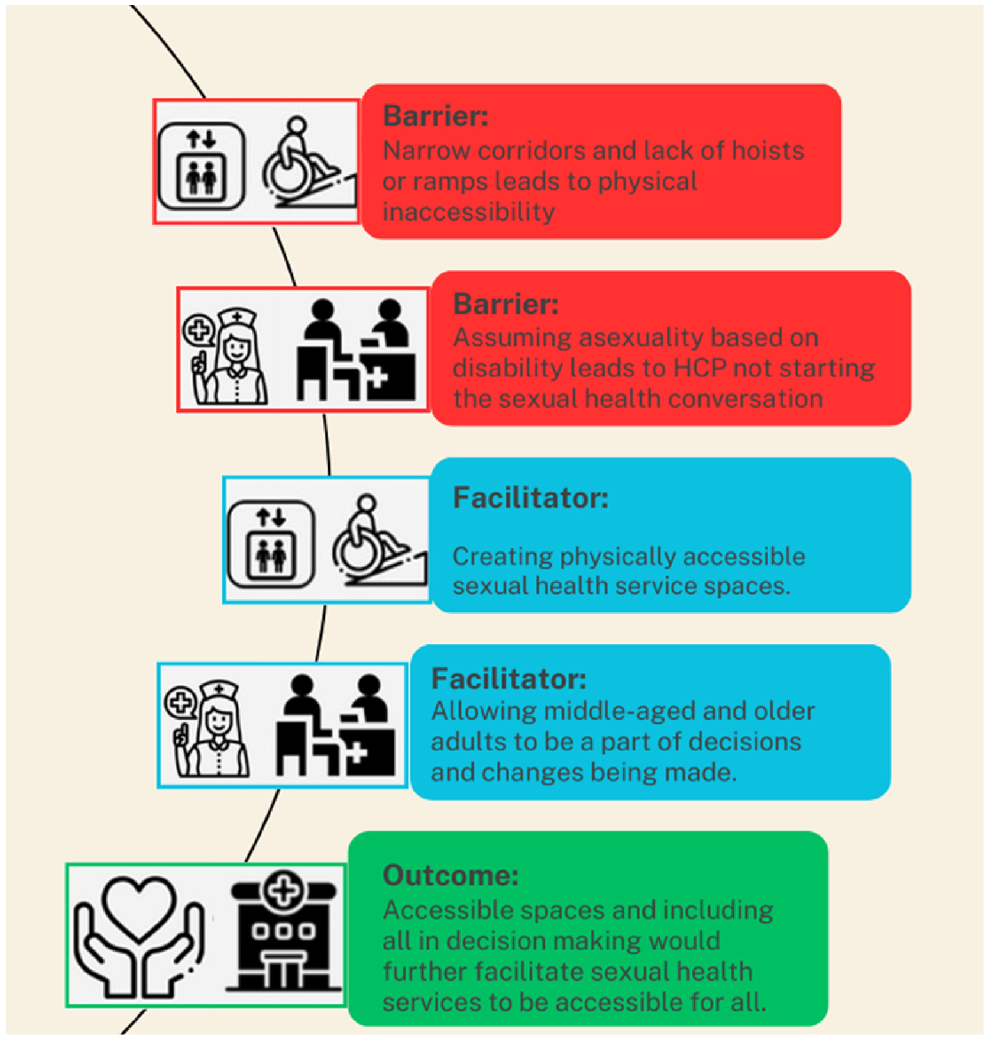

This study investigates barriers and facilitators to accessing SHS among individuals aged 45 years and older in the UK based on their lived experiences. The identified barriers related to systemic factors, such as physical facility accessibility, are shown in Fig. 3. Fig. 3 demonstrates that most facilitators we identified are system-based, as the identified facilitators are more heavily mapped on to systemic factors, such as approachability and acceptability, rather than individual factors, such as ability to seek. This suggests that enhancing access would necessitate changes at the facility and structural levels. This study expands the literature by focusing on older adults and disabled adults over 45 years of age, working in partnership with community organisations serving disabled people, and identifying modifiable elements of SHS to improve access.

Diagram showing barriers and facilitators to accessing SHS in England for middle-aged and older adults who are physically disabled.

Our data suggest that physical inaccessibility is a prominent barrier to older adults accessing SHS in the UK. This contrasts previous research that has not observed this trend.1,11,12,15 However, other sexual health studies focused more on middle-aged people, not recruiting elderly participants or using targeted recruitment to include participants with a higher burden of disability.1 The prevalence of physical disability increases with age, and particularly the elderly have physical accessibility needs, as well as those with life-long disabilities.25 However, these accessibility issues have not been widely reported in sexual health research studies in the UK. The results of this study suggest that SHS are structurally inaccessible, particularly to older adults and people with disabilities. Adults with disabilities appear to inherently face more barriers to accessing sexual healthcare services as a sub-group and this led to an important focus area in our results and key findings.

Our study highlighted several physical accommodations that would be likely to increase access to SHS (Fig. 3). This included more hoists, widening corridors, installing lifts or ramps, and offering home visits for those unable to access clinics. This is consistent with other studies that have researched people with disabilities accessing medical services. Use of general medical services is lower when the centres are not physically accessible.26,27 However, the disabled population is diverse, and addressing their sexual health needs will require a multi-faceted approach tailored to the individual. Although improving physical accessibility is essential, it is unlikely to serve as a universal solution for addressing all aspects of sexual health disparities among individuals with disabilities.

The lack of understanding among HCPs about the sexual needs of older and disabled adults can make them feel burdensome when seeking SHS. There seems to be an intensified stigma surrounding sexual activity as people age, particularly for middle-aged and older adults, which is only exacerbated by their disability status. This demographic is often stereotyped as asexual, meaning HCP seldom raise sexual health during consultations and can have dismissive responses when these issues are raised.1,11–14 This results in many older individuals fearing judgment and doubting their entitlement to access sexual health resources.

Our results show that involving older adults in decision making can facilitate access to SHS. A previous study conducted by the WHO in 2007 found that involving men and boys in decision-making processes related to sexual health positively impacts access to SHS.28 By actively engaging older adults in the development of strategies, HCPs would gain valuable insights into their specific needs and challenges. Through community-engaged approaches, we can identify and address issues more effectively with input from older adults themselves. This inclusive approach fosters a sense of ownership and empowerment within the community, leading to greater trust and confidence in SHS. Overall, involving older adults in decision-making processes not only improves the design and delivery of SHS but also promotes inclusivity and empowerment within the community. By prioritising their voices and experiences, we can create more accessible, responsive, and effective SHS that meet the diverse needs of this demographic.

This study has some limitations worth noting. First, our recruitment efforts were limited to England, preventing us from including participants from other geographical locations in the UK. Second, despite our extensive advertising in care homes, we encountered challenges in recruiting sufficient participants aged over 65 years or residing in care facilities. However, we successfully achieved a diverse participant pool, encompassing various disability statuses, age groups, and sexual identities, which enriched the breadth of our findings. Additionally, our sample size of 22 interviews allowed us to reach data saturation, a significant strength that enhances the robustness of our research outcomes. The study participant demographics were also slightly unequal, with an over-representation of males and non-disabled participants. Lastly, some barriers identified are more specific to minority sub-groups within this study population, but it is important to raise the point that those with intersectional needs face additional barriers in addition to those faced by the general older population.

This study illuminates the multi-faceted barriers encountered by middle-aged and older adults in accessing SHS within the UK. To advance future research, it is crucial to collect data on the costs associated with making spaces physically accessible, providing critical insights for informing clinical practice. Policy reform is imperative to ensure that SHS are inclusively designed, effectively implemented, and rigorously monitored to cater to the needs of this demographic. Moreover, there is a pressing need for future research to actively involve older adults in intervention design and to delve into their preferences regarding accessing SHS. Such endeavours will foster improvements in service delivery, ultimately enhancing the overall sexual health outcomes for middle-aged and older adults.

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest

Dr Dan Wau is an Associate Editor, and Dr Joseph D. Tucker and Dr Jason J. Ong are co-Editors-in-Chief, for Sexual Health but were not involved in the peer review or decision-making process for this paper. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Declaration of funding

This work received funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) grant number: ES/T014547/1.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Tom Shakespeare and Tracey Jannaway for providing feedback on the methods and initial data analysis. We thank Sophie Bowen for support with conducting interviews. We thank Opening Doors London and Independent Living Alternatives for participant recruitment.

References

1 Ezhova I, Savidge L, Bonnett C, Cassidy J, Okwuokei A, Dickinson T. Barriers to older adults seeking sexual health advice and treatment: a scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud 2020; 107: 103566.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

2 Lee DM, Nazroo J, O’Connor DB, Blake M, Pendleton N. Sexual health and well-being among older men and women in England: findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Arch Sex Behav 2016; 45(1): 133-44.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

3 Khan J, Greaves E, Tanton C, Kuper H, Shakespeare T, Kpokiri EE, et al. Sexual behaviours and sexual health among middle-aged and older adults in Britain: a latent class analysis of the Natsal-3. BMJ 2021; 99(3): 1-28.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

4 WHO. Ageing and health. WHO; 2024. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health [cited 26 August 2023]

5 Rabathaly PA, Chattu VK. Emphasizing the importance of sexual healthcare among middle and old age groups: a high time to re-think? J Nat Sci Biol Med 2019; 10(1): 91.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

6 Merghati-Khoei E, Pirak A, Yazdkhasti M, Rezasoltani P. Sexuality and elderly with chronic diseases: a review of the existing literature. J Res Med Sci 2016; 21(1): 136.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

7 Carrillo Gonzalez GM, Sanchez Herrera B, Chaparro Díaz OL. Chronic disease and sexuality. Inves Educ Enferm 2013; 31(2): 295-304.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

8 Youssef E, Wright J, Delpech V, Davies K, Brown A, Cooper V, et al. Factors associated with testing for HIV in people aged ≥50 years: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2018; 18(1): 1204.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

9 United Nations. World population projected to reach 9.8 billion in 2050, and 11.2 billion in 2100. United Nations; 2017. Available at https://www.un.org/en/desa/world-population-projected-reach-98-billion-2050-and-112-billion-2100

10 World Health Organization. Defining sexual health. World Health Organization; 2025. Available at https://www.who.int/teams/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-research/key-areas-of-work/sexual-health/defining-sexual-health [cited 26 August 2023]

11 Hinchliff S, Gott M. Seeking medical help for sexual concerns in mid- and later life: a review of the literature. J Sex Res 2011; 48(2–3): 106-17.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

12 Bauer M, Haesler E, Fetherstonhaugh D. Organisational enablers and barriers to the recognition of sexuality in aged care: a systematic review. J Nurs Manag 2019; 27(4): 858-68.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

13 Conyers H, Wu D, Kpokiri E, Zhang Q, Hinchliff S, Shakespeare T, et al. Barriers and facilitators to accessing sexual health services for older LGBTQIA+ adults: a global scoping review and qualitative evidence synthesis. Sex Health 2023; 20(1): 9-19.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

14 Haesler E, Bauer M, Fetherstonhaugh D. Sexuality, sexual health and older people: a systematic review of research on the knowledge and attitudes of health professionals. Nurse Educ Today 2016; 40: 57-71.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

15 Gott M. Barriers to seeking treatment for sexual problems in primary care: a qualitative study with older people. Fam Pract 2003; 20(6): 690-5.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

16 Stokes-Lampard H, Thompson E, Gracie H. Sexual and reproductive health TIME TO ACT. Royal College of General Practitioners; 2018. Available at https://www.rcgp.org.uk/representing-you/policy-areas/sexual-reproductive-health [cited 26 August 2023]

17 Office for National Statistics. Age groups. Office for National Statistics; 2023. Available at https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/uk-population-by-ethnicity/demographics/age-groups/latest#:~:text=data%20shows%20that%3A-,29.1%25%20of%20all%20people%20in%20England%20and%20Wales%20(17.3%20million,aged%2060%20years%20and%20over [cited 26 August 2023]

18 Levesque J-F, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of Health Systems and populations. Int J Equity Health 2013; 12(1): 18.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

19 Cu A, Meister S, Lefebvre B, Ridde V. Assessing healthcare access using the Levesque’s conceptual framework – a scoping review. Int J Equity Health 2021; 20(1): 116.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

20 Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3(2): 77-101.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

21 Gore-Gorszewska G. “Why not ask the doctor?” barriers in help-seeking for sexual problems among older adults in Poland. Int J Public Health 2020; 65(8): 1507-15.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

22 Schaller S, Traeen B, Lundin Kvalem I. Barriers and facilitating factors in help-seeking: a qualitative study on how older adults experience talking about sexual issues with healthcare personnel. Int J Sex Health 2020; 32(2): 65-80.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

23 Rutte A, Welschen LMC, van Splunter MMI, Schalkwijk AAH, de Vries L, Snoek FJ, et al. Type 2 diabetes patients’ needs and preferences for care concerning sexual problems: a cross-sectional survey and qualitative interviews. J Sex Marital Ther 2016; 42(4): 324-37.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

24 Fileborn B, Lyons A, Heywood W, Hinchliff S, Malta S, Dow B, et al. Talking to healthcare providers about sex in later life: findings from a qualitative study with older Australian men and women. Australas J Ageing 2017; 36(4): E50-6.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

25 Wellard N, Colvin H. Disability by age, sex and deprivation, England and Wales: census 2021. Office for National Statistics; 2023. Available at https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/disability/articles/disabilitybyagesexanddeprivationenglandandwales/census2021#:~:text=After%20the%20ages%20of%2070,aged%2090%20years%20and%20over [cited 26 August 2023]

26 Tun W, Okal J, Schenk K, Esantsi S, Mutale F, Kyeremaa RK, et al. Limited accessibility to HIV services for persons with disabilities living with HIV in Ghana, Uganda and Zambia. J Int AIDS Soc 2016; 19(5S4): 20829.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

27 Moscoso-Porras M, Fuhs AK, Carbone A. Access barriers to medical facilities for people with physical disabilities: the case of Peru. Cad Saúde Pública 2019; 35(12): e00050417.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

28 Barker G, Ricardo C, Nascimento M, World Health Organization, Instituto Promundo. Engaging men and boys in changing gender-based inequity in health: evidence from programme interventions; 2007. Available at https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/43679