Preferences and willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV among men who have sex with men in mainland China and Hong Kong

Jiajun Sun A B , Jason J. Ong

A B , Jason J. Ong  A B C , Heather-Marie Schmidt

A B C , Heather-Marie Schmidt  D E , Curtis Chan

D E , Curtis Chan  F , Benjamin R. Bavinton

F , Benjamin R. Bavinton  F , Kimberly Elizabeth Green

F , Kimberly Elizabeth Green  G , Nittaya Phanuphak

G , Nittaya Phanuphak  H I , Midnight Poonkasetwattana J , Nicky Suwandi K , Doug Fraser F , Weiming Tang

H I , Midnight Poonkasetwattana J , Nicky Suwandi K , Doug Fraser F , Weiming Tang  L , Michael Cassell M , Hua Boonyapisomparn K , Edmond Pui Hang Choi

L , Michael Cassell M , Hua Boonyapisomparn K , Edmond Pui Hang Choi  N , Lei Zhang

N , Lei Zhang  A B O P # * and Warittha Tieosapjaroen A B # *

A B O P # * and Warittha Tieosapjaroen A B # *

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

# Co-senior author

Handling Editor: Ian Simms

Abstract

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake remains low in mainland China and Hong Kong. We examined preferences for different PrEP modalities among men who have sex with men (MSM) in mainland China and Hong Kong.

We conducted a cross-sectional online survey from May to November 2022 in mainland China and Hong Kong. Eligible participants were aged ≥18 years, identified as MSM and self-reported HIV-negative, or unknown HIV status. Random forest models and SHapley Additive exPlanations analyses were used to identify key factors influencing preferences for and willingness to use six PrEP options: (1) daily oral, (2) on-demand oral, (3) monthly oral, (4) two-monthly injectable, (5) six-monthly injectable, and (6) implantable PrEP.

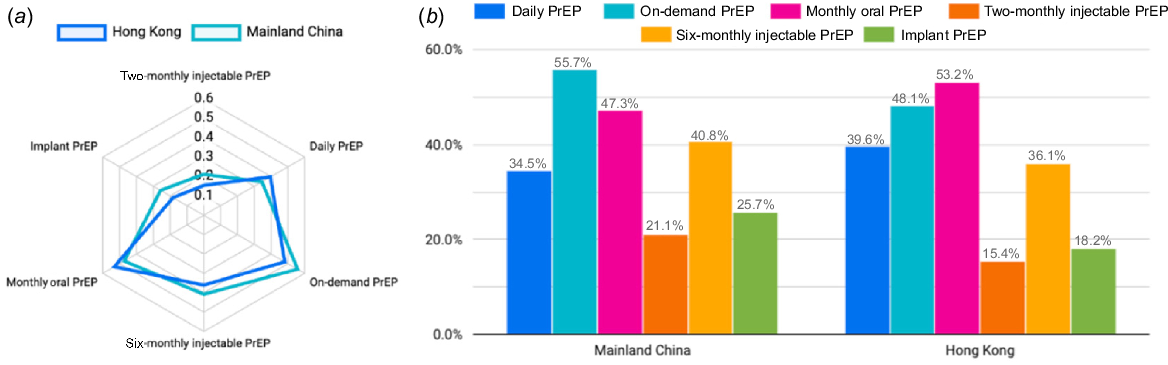

Among 2142 participants (mainland China: 1604; Hong Kong: 538), the mean age was 28.4 (±7.0) years in mainland China and 34.7 (±9.5) years in Hong Kong. Current PrEP use was similar between mainland China and Hong Kong (18.0% vs 17.8%, P = 0.93), with an additional 10.5% and 8.0% reporting past PrEP use (P = 0.11), respectively. A greater proportion of participants from mainland China preferred on-demand PrEP compared to those from Hong Kong (55.7% vs 48.1%, P < 0.01), whereas more participants from Hong Kong preferred monthly oral PrEP (53.2% vs 47.3%, P = 0.02). Willingness to use non-oral options was lower, with two-monthly injectable PrEP preferred by 21.1% (19.1–23.1%) in mainland China and 15.4% (12.3–18.5%) in Hong Kong (P < 0.01). Among Hong Kong participants, condom use frequency and migration status were important predictors of willingness to use both oral and injectable PrEP options. Current PrEP use status and PrEP attitudes were consistently important predictors. Additionally, individuals who preferred six-monthly injectable PrEP tended to dislike the two-monthly option.

On-demand and monthly PrEP options remain the preferred choices, though the monthly oral option is neither proven nor available. However, the factors influencing these preferences vary, highlighting the need for tailored and targeted approaches to PrEP implementation.

Keywords: China, HIV prevention, Hong Kong, machine learning, men who have sex with men, pre-exposure prophylaxis, Preference research, random forest.

Introduction

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimates that the number of people using pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV in 2022 in Asia and the Pacific was less than 5% of the 2025 target.1,2 As of the end of 2023, only 3.5 million individuals had used PrEP during the year, representing just 16.5% of the global target (21.2 million).2 This shortfall is apparent in mainland China and Hong Kong. The National Health Commission of China has been working on increasing the availability and awareness of PrEP, but progress remains slow.3 Increasing PrEP uptake is crucial for reducing HIV incidence among key populations, particularly men who have sex with men (MSM), who remain affected by HIV.4

In Hong Kong, PrEP is available but not yet widely used. The Hong Kong Department of Health issued guidelines for PrEP in 2022,5,6 and according to the 2020 HIV and AIDS Response Indicator Survey, 6.3% of MSM in Hong Kong used PrEP in the past year.6 However, by 2022, there was still no formal PrEP program within the public healthcare system.7 In contrast, mainland China has been slower in rolling out PrEP, with limited general availability, although pilot programs have begun in some major cities.8 Both Hong Kong and mainland China have lower public awareness and access compared to countries like the United States and some of those in Europe.9–11 In terms of cost, PrEP is not available through public healthcare services in Hong Kong and can only be obtained from private providers at a high cost or overseas suppliers,12 with wholesale costs averaging HK$6000 (US$ 772.16) per month.13 In mainland China, PrEP is mainly accessible through private providers and is relatively expensive, costing approximately ¥2000 RMB (US$ 274.87) per bottle (30 pills), with no widespread government subsidy, leading many to seek international or online sources.10,14 According to national guidelines, the indications for PrEP use in both mainland China and Hong Kong are similar, focusing on key populations, such as MSM, people who inject drugs, and those with HIV-positive partners.9,15–17

In 2022, WHO recommended a new long-acting injectable PrEP product, cabotegravir (CAB-LA), to be offered to people at substantial risk of HIV as part of combined HIV prevention approaches.18 Providing choice in PrEP products, including the addition of CAB-LA, is expected to help accelerate PrEP uptake.19 However, CAB-LA for HIV prevention is not yet broadly available in most parts of the world. Although ViiV Healthcare holds the patents and has approved CAB-LA in some countries, its rollout has been primarily limited to the United States, Zambia, South Africa, and other sub-Saharan African countries. Although registered in China in 2024,20 challenges such as high production costs and limited global supply have restricted the distribution of CAB-LA, especially in upper-middle-income countries, like China.21 Little is known about awareness and willingness to use non-oral PrEP22,23 among MSM in mainland China and Hong Kong. Research on awareness and willingness to use non-oral PrEP can help identify key factors for its implementation.

There are multiple factors influencing awareness and willingness to use PrEP, many of which are interrelated, making it challenging to identify the key drivers of PrEP uptake. Identifying these drivers is essential for policymakers and researchers working in HIV prevention.24,25 Traditional statistical methods, such as logistic regression, have been used to explore the predictors of PrEP awareness and willingness towards PrEP use.26,27 However, these approaches often assume linear relationships between variables and may fail to capture complex interactions between demographic, behavioural, and societal factors influencing PrEP use. Machine learning offers a valuable approach to analysing complex datasets, helping to uncover key factors that influence PrEP use. The random forest classifier is a widely used machine learning technique that combines multiple decision trees to make predictions. This approach provides a more flexible and robust framework that can identify non-linear patterns and subgroup-specific trends.28,29 By incorporating the model, it could provide new insights into how different factors interact to influence PrEP preferences, which may not be apparent in traditional regression-based analyses. In this study, respondents provided their awareness of and willingness to use PrEP through questionnaire responses, selecting the options that best aligned with their circumstances, risk behaviours, and intention to use PrEP. These responses were analysed using the random forest classifier to determine which factors contribute most to the outcome of willingness (i.e. intention to use PrEP). This study aims to build a machine learning model to evaluate the primary drivers of PrEP use and explore the similarities and differences in influencing factors between mainland China and Hong Kong.

Methods

Study design and participants

The PrEP APPEAL survey was a cross-sectional online study conducted between May and November 2022 across 15 countries and territories in Asia. A full list of countries included in the survey is listed in the PrEP APPEAL survey report.30 This analysis will be restricted to participants from mainland China and Hong Kong Special Admistrative Region. There were paid and unpaid advertising in both mainland China and Hong Kong. We used the apps ’WeChat’ and ’Grindr’ for mainland China, and ’Hornet’ and ’Grindr’ for Hong Kong. Both also used community mailing lists. In mainland China, the survey was conducted in simplified Chinese, and in Hong Kong, it was conducted in traditional Chinese or English. The sample size for this study was calculated to ensure sufficient statistical power to detect differences between groups. We aimed for a statistical power of 80% to detect a moderate effect size at a 5% significance level. Given the expected proportions in each group, the calculated minimum sample size was 2000 MSM (1400 from mainland China and 600 from Hong Kong), which is consistent with the number of respondents included in the study.

To encourage participation, respondents who completed the survey were offered the opportunity to enter a prize draw. The prize value was ¥1000 (US$ 137.48) in mainland China and HK$1500 (US$ 192.90) in Hong Kong. Eligibility criteria for participation required individuals to be adults aged 18 years or older, self-report as HIV-negative or unknown, currently residing in mainland China or Hong Kong, and self-identifying as MSM, including transgender men.

Variables for machine learning input

Participants were categorised into two groups based on their current place of residence: (1) mainland China or (2) Hong Kong. The survey included a range of questions covering demographic characteristics, behavioural patterns, and preferences for PrEP. For their preferences for PrEP, participants were presented with a multiple-choice question: ‘There are different types of PrEP available now, and new forms are in development. If all these options were available and equally effective in protecting you from HIV, which would you choose?’. Respondents were provided with six options: (1) one oral pill every day (‘daily PrEP’); (2) oral pills around the time of sexual encounters (‘on-demand PrEP’); (3) one oral pill every month (‘monthly PrEP’); (4) PrEP injections every 2 months (‘two-monthly injectable PrEP’); (5) PrEP injections every 6 months (‘six-monthly injectable PrEP); and (6) a slow-release, removable PrEP implant lasting about 1 year (‘implant PrEP’).

For the analysis, six PrEP preference variables were identified as the primary outcomes of willingness to use, with each PrEP option treated as a dependent variable in separate models. The independent variables included demographic and behavioural data, along with the other five PrEP options. In Table S1, all independent variables were classified into three categories: (1) binary, (2) continuous, and (3) categorical. The chi-squared test was used to perform intergroup statistical comparisons. A P-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. To address potential multicollinearity among the independent variables, we applied the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to assess correlations. During the VIF analysis, 20 independent variables with VIF values ≥10 were excluded to address multicollinearity, enhancing the model’s stability and interpretability. The removed variables primarily included categorical indicators (such as uncommon place of birth), PrEP access methods not covered in the questionnaire options, and whether participants had previously used PrEP. This refinement ensured that the remaining features were less correlated, allowing the model to generate more reliable and meaningful predictions. The study flowchart is shown in Fig. 1.

Random forest model and importance feature analysis

The random forest algorithm has become a widely successful method for both classification and regression tasks.31 This algorithm, grounded in statistical learning theory, uses Bootstrap resampling to generate multiple versions of the training dataset. A decision tree model is built for each resampled dataset, and the final prediction is made by aggregating the results through a majority voting mechanism. We selected the random forest model for this analysis due to its robustness and ability to handle high-dimensional data, such as the questionnaire responses. Unlike other machine learning algorithms, random forest performs well even with duplicate or incomplete data and can capture complex relationships between features.

We applied a random forest classifier, implemented using Python 3.12 and Sklearn 1.5.2, to analyse the questionnaire data. Model training involved parameter optimisation using random search and five-fold cross-validation. The dataset was randomly split, with 80% of the participants’ responses used for training and the remaining 20% for testing. To ensure the reproducibility of results, we set the random seed to 42.

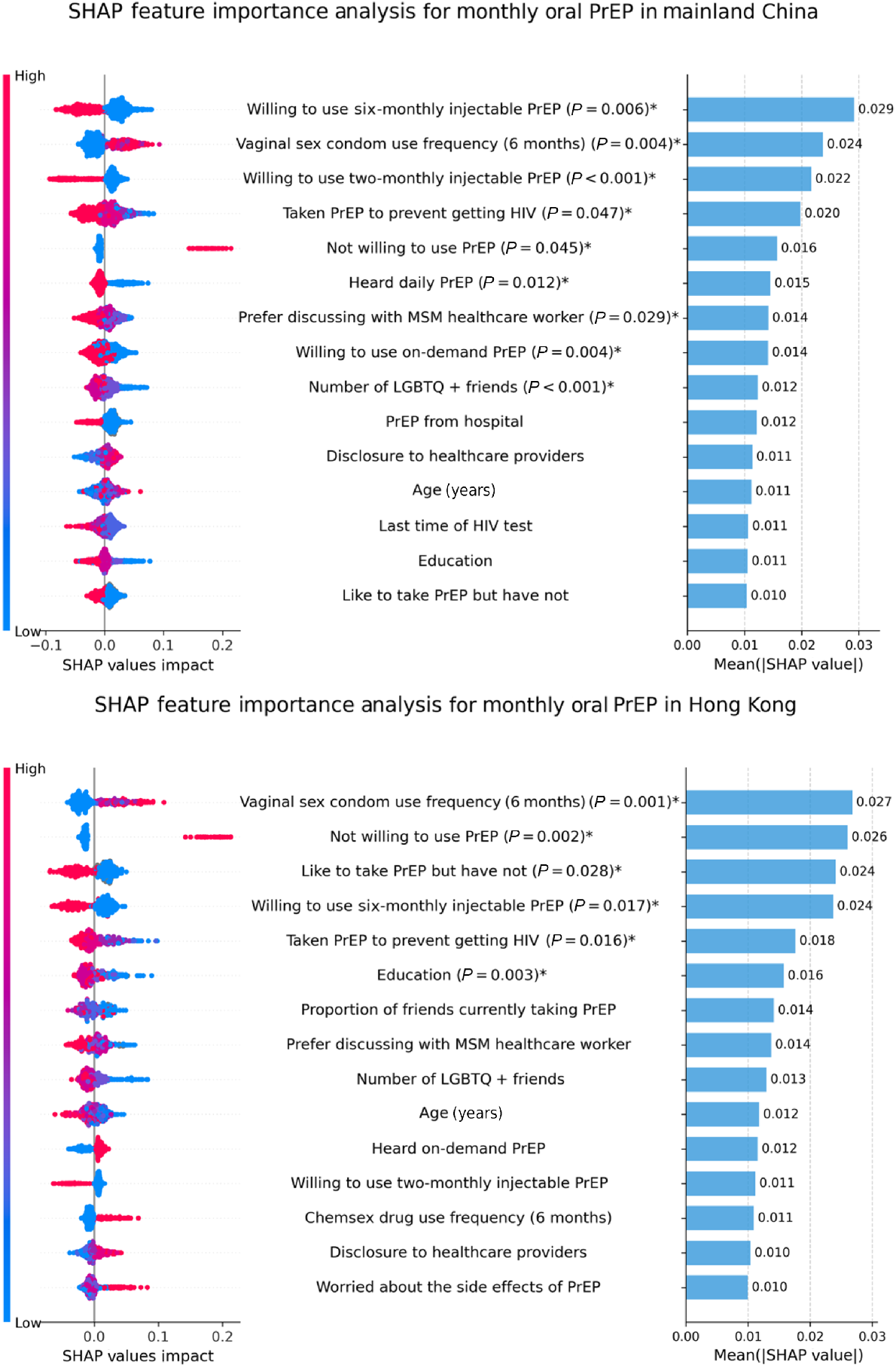

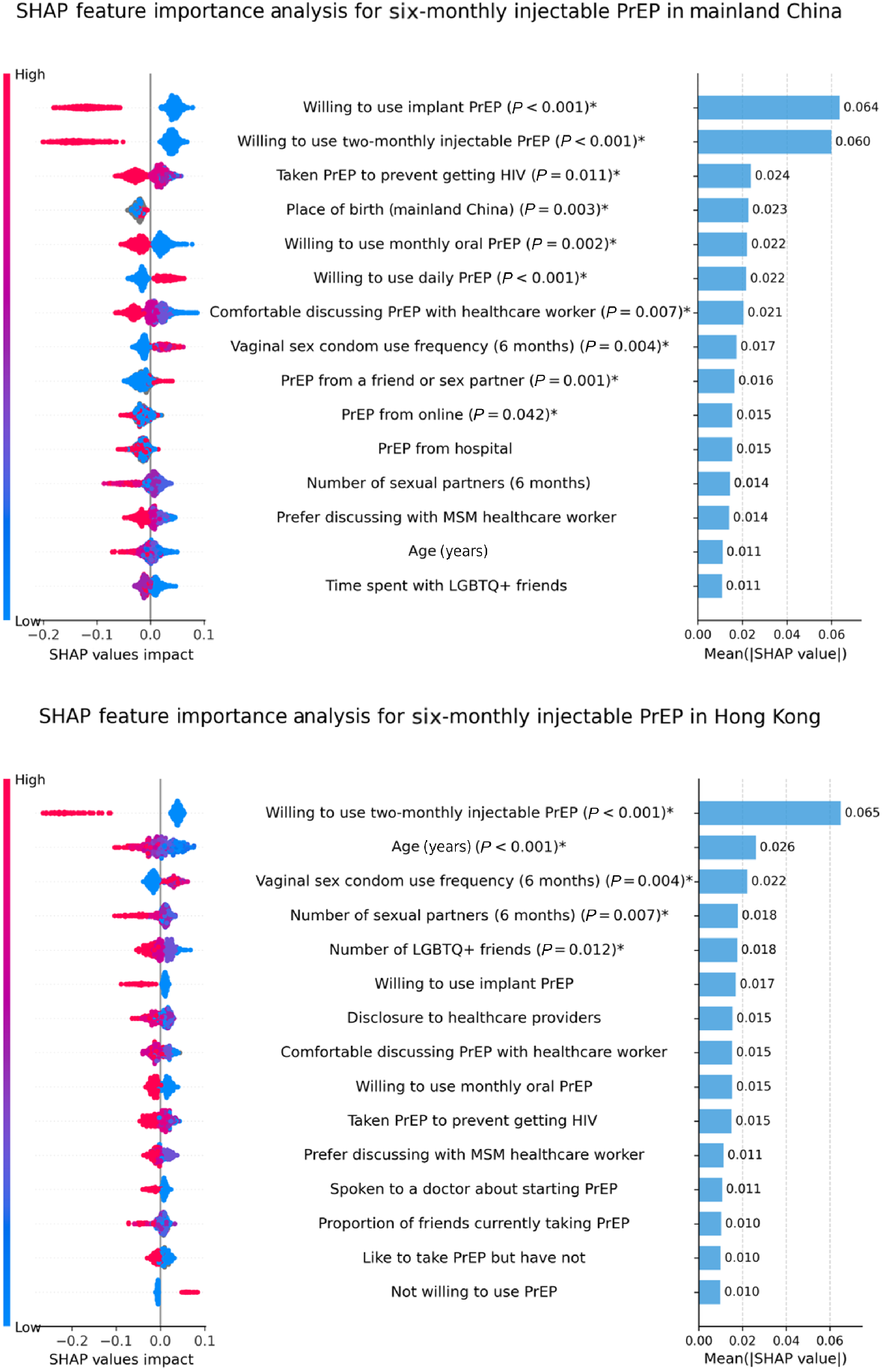

SHAP figure

For model interpretation, we used SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), a method based on cooperative game theory.32 SHAP assigned an importance value to each feature by evaluating its contribution across all possible feature combinations. It provided an average marginal contribution of each feature to the model’s output, offering a comprehensive assessment of feature importance.

The SHAP values provided insight into the impact of each feature on the model’s predictions for the preference for PrEP. The X-axis represented the SHAP value, which quantified the influence of each feature on the model’s output; positive values indicated that the feature contributes to a higher outcome, such as a stronger preference for PrEP, whereas negative values suggested a push toward a lower outcome, reflecting reluctance or a lower preference. This correlation between the SHAP values and PrEP preferences may explain how each feature influenced participants’ PrEP choices. The Y-axis displayed the top 15 most important features affecting the model’s predictions. The colour bar denoted the value of each feature for individual participants, with red indicating a high feature value, blue representing a low feature value, and grey signifying a blank value. Each dot corresponded to an individual participant’s SHAP value for that specific feature, and the horizontal spread of the dots illustrated the variability in the impact of that feature on the outcome; a wider spread indicated greater variation in how that feature influences predictions across participants. This comprehensive representation aided in understanding the relative importance and effect of various factors on participant preferences for PrEP.

We focus on the top 15 most important features based on a balance between capturing the most influential variables while avoiding the inclusion of too many features that could lead to model complexity and overfitting. We found that the top 15 features provided a sufficient representation of the factors most strongly affecting participants’ preferences for PrEP without losing the interpretability of the model. Selecting fewer features would have potentially excluded some key predictors while selecting more could have introduced noise and reduced the clarity of the results. Therefore, we considered 15 to be an optimal number, as it offered a comprehensive yet manageable set of features for further analysis.

To further analyse the significance of the top 15 most important features identified by SHAP, we constructed a logistic regression model, with the PrEP option as the dependent variable and the top 15 features as independent variables. We applied backward elimination to refine the model by iteratively removing non-significant features, allowing us to focus on the most impactful predictors. The model details are shown in Tables S2 and S3. We calculated P-values for each feature to evaluate statistical significance, with features showing a P-value of ≤0.05 being considered statistically significant. Significant features were marked with an asterisk to indicate their importance in predicting the willingness to use PrEP. Although SHAP values provide valuable insights into the relationship between features and model predictions, they do not directly assess statistical significance. The lack of statistical significance in the logistic regression model does not necessarily mean that a feature is not predictive or relevant. It may indicate that the feature’s effect is not strong enough to achieve statistical significance given the sample size or the specific model structure used.

Results

Characteristics of participants

As shown in Table 1, 2142 MSM completed the survey and were included in this analysis, with 1604 (74.9%) residing in mainland China and 538 (25.1%) in Hong Kong. Among respondents included in the analyses, the mean age of mainland China and Hong Kong was 28.4 (±7.0) and 34.7 (±9.5) years, respectively. All respondents reported male as their sex at birth, except one respondent (0.2%) in Hong Kong, who identified as female sex at birth.

| Mainland China | Hong Kong | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age (years) | Mean 28.4 | s.d. 7.0 | Mean 34.7 | s.d. 9.5 | |

| Sex at birth | |||||

| Male | 1604 | 100.0 | 537 | 99.8 | |

| Female | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Sexual identity | |||||

| Gay or homosexual | 1302 | 81.2 | 451 | 83.8 | |

| Bisexual or pansexual | 230 | 14.3 | 76 | 14.1 | |

| Heterosexual or straight | 17 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| I don’t usually use a term | 45 | 2.8 | 8 | 1.5 | |

| I use a different term | 10 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Education level | |||||

| No schooling | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Primary/elementary school | 3 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Junior high school | 20 | 1.2 | 9 | 1.7 | |

| Senior high school | 125 | 7.8 | 79 | 14.7 | |

| Diploma/trade/vocational certificate | 141 | 8.8 | 97 | 18.0 | |

| Undergraduate degree | 982 | 61.2 | 206 | 38.3 | |

| Postgraduate degree | 316 | 19.7 | 145 | 27.0 | |

| Missing | 15 | 0.9 | 2 | 0.4 | |

| Employment | |||||

| Full-time | 1076 | 67.1 | 407 | 75.7 | |

| Part-time | 92 | 5.7 | 42 | 7.8 | |

| Unemployed | 107 | 6.7 | 26 | 4.8 | |

| Student | 309 | 19.3 | 51 | 9.5 | |

| Retired | 3 | 0.2 | 6 | 1.1 | |

| Other | 13 | 0.8 | 5 | 0.9 | |

| Missing | 4 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| PrEP awareness and use | |||||

| Never heard of PrEP | 64 | 4.0 | 20 | 3.7 | |

| Heard of PrEP but never used PrEP | 1009 | 62.9 | 358 | 66.5 | |

| Used in the past but not currently | 168 | 10.5 | 43 | 8.0 | |

| Currently using PrEP | 289 | 18.0 | 96 | 17.8 | |

| Missing | 74 | 4.6 | 21 | 3.9 | |

| Chemsex in the past 6 months | |||||

| No sexual partner | 1162 | 72.4 | 430 | 79.9 | |

| No chemsex | 359 | 22.4 | 85 | 15.8 | |

| Had chemsex | 78 | 4.9 | 22 | 4.1 | |

| Missing | 5 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| STI diagnosis in the past 6 months | |||||

| No | 1525 | 95.1 | 504 | 93.7 | |

| Yes | 77 | 4.8 | 34 | 6.3 | |

| Missing | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Involvement in commercial sex in the past 6 months | |||||

| No | 1521 | 94.8 | 523 | 97.2 | |

| Yes | 82 | 5.1 | 15 | 2.8 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Sexual partner in the past 6 months | |||||

| Single | 149 | 9.3 | 44 | 8.2 | |

| One partner | 510 | 31.8 | 92 | 17.1 | |

| Multiple partners | 945 | 58.9 | 402 | 74.7 | |

| Condomless anal sex in the past 6 months | |||||

| No sex | 275 | 17.1 | 99 | 18.4 | |

| Always used condoms | 644 | 40.1 | 140 | 26.0 | |

| Not always used condoms | 684 | 42.6 | 298 | 55.4 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Sharing injecting equipment in the past 6 months | |||||

| Not injecting drugs | 1531 | 95.4 | 497 | 92.4 | |

| Injecting drug without sharing equipment | 69 | 4.3 | 40 | 7.4 | |

| Injecting drug and sharing equipment | 2 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.2 | |

| Missing | 2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

s.d., standard deviation; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Regarding PrEP use, 10.5% of residents in mainland China and 8.0% of residents in Hong Kong reported having taken PrEP in the past but are not currently using it (chi-squared test, P = 0.11), and 18.0% of mainland China residents and 17.8% of Hong Kong residents reported currently taking PrEP (chi-squared test, P = 0.93). In the past 6 months, 4.9% of residents in mainland China reported having chemsex, 4.8% reported a sexually transmitted infection (STI) diagnosis, 5.1% were paid for sex in the past 6 months, 58.9% had multiple sexual partners, and 0.1% shared injecting equipment while using drugs. Meanwhile, 4.1% of residents in Hong Kong reported having chemsex, 6.3% reported an STI diagnosis, 2.8% were involved in paid sex, 74.7% had multiple sexual partners, and 0.2% shared injecting equipment in the past 6 months.

Overall preference for PrEP types

The willingness to utilise PrEP varied among residents of mainland China and Hong Kong. The ratio was defined as the proportion of individuals expressing a willingness to use a specific PrEP type, calculated by dividing the number of willing individuals by the total population. As shown in Fig. 2, a greater proportion of participants from mainland China preferred on-demand PrEP compared to those from Hong Kong (55.7% vs 48.1%, chi-squared test, P < 0.01), whereas more participants from Hong Kong preferred monthly oral PrEP (53.2% vs 47.3%, chi-squared test, P = 0.02). In contrast, the willingness to use two-monthly injectable PrEP options was lower, at 21.1% (19.1–23.1%) among mainland Chinese residents and 15.4% (12.3–18.5%) among those in Hong Kong (chi-squared test, P < 0.01). Similarly, receptiveness to long-acting implant PrEP was limited, with 25.7% (23.6–27.8%) of residents in mainland China and 18.2% (14.9–21.5%) in Hong Kong indicating willingness to use (chi-squared test, P < 0.01).

On-demand PrEP

As shown in Fig. 3, taking on-demand PrEP was the most influential factor in both mainland China and Hong Kong. In Hong Kong, this was followed by interest in taking PrEP without having started and by age. In mainland China, reluctance to use PrEP and interest in taking PrEP without having started were ranked second and third, respectively.

The SHAP summary plots provided insights into how each factor affected willingness to use on-demand PrEP. In Hong Kong, the current use of on-demand PrEP showed a negative relationship with the outcome, indicating that individuals who were not currently using on-demand PrEP may be more inclined to consider it. Similarly, interest in taking PrEP without having started also exhibited a negative effect, indicating that individuals who had expressed willingness to use but had not yet accessed PrEP might be less likely to consider this option. Age displayed a positive relationship, with older participants showing a greater willingness to use on-demand PrEP. Reluctance to use PrEP showed a positive association with the willingness to use on-demand PrEP, ranking fourth in importance, suggesting that individuals who initially expressed reluctance towards PrEP might be more open to considering the flexibility offered by on-demand dosing. In mainland China, currently taking on-demand PrEP and interest in taking PrEP without having started similarly exhibited a negative effect on the outcome. Reluctance to use PrEP exhibited a positive association with willingness to use on-demand PrEP.

Additionally, differences were observed in other factors. In Hong Kong, the frequency of condom use during vaginal sex in the past 6 months ranked fifth and displayed a positive association, suggesting that individuals who used condoms more frequently during vaginal sex might be more open to considering on-demand PrEP. In contrast, this factor did not appear among the top 15 most influential factors for participants in mainland China, indicating its lesser importance in that context. In Hong Kong, willingness to use daily PrEP showed a negative relationship with willingness to use on-demand PrEP, ranking 15th in importance, indicating that those willing in daily PrEP might be less inclined to consider the on-demand option. In mainland China, although this factor similarly displayed a negative association, it exhibited greater influence by ranking 12th in importance.

Daily oral PrEP

In both mainland China and Hong Kong, current use of on-demand PrEP had a positive association with willingness to use daily PrEP and ranked as the top factor, suggesting that current on-demand PrEP users were more open to considering daily PrEP as well (Fig. 4).

In Hong Kong, the proportion of friends currently using PrEP ranked second and showed a negative association, indicating that participants with more friends using PrEP tended to have a lower willingness to use daily PrEP. In contrast, this factor ranked 11th in mainland China, where it displayed a positive association.

Across both mainland China and Hong Kong, reluctance to use PrEP exhibited a positive association with the willingness to use daily PrEP, suggesting that participants initially not willing to use PrEP showed greater willingness to use the daily PrEP compared to those who were already inclined toward PrEP.

In Hong Kong, being born in the current country exhibited a negative relationship with the outcome, indicating that individuals who had migrated to Hong Kong showed greater willingness to use daily PrEP compared to those born locally. Similarly, participants who did not know friends had a positive attitude toward PrEP exhibited a negative association with daily PrEP acceptance, suggesting that individuals who were uncertain about their peers’ attitudes toward PrEP might be more open to considering daily PrEP use. These factors’ influences appeared to be specific to Hong Kong, as they did not emerge as predictors in the mainland China analysis.

Monthly oral PrEP

As shown in Fig. 5, in Hong Kong, the frequency of condom use during vaginal sex in the past 6 months emerged as the most influential factor, showing a positive relationship with the outcome, indicating that individuals who more frequently used condoms during vaginal sex were more open to considering monthly PrEP. Similarly, reluctance to use PrEP ranked second and displayed a positive association, suggesting that those initially resistant to PrEP might be more receptive to the monthly oral PrEP specifically. However, this factor, ranked fifth, was not particularly influential among MSM in mainland China.

The analysis also highlighted willingness patterns in PrEP preferences across mainland China and Hong Kong. In Hong Kong, interest in taking PrEP without having started demonstrated a negative relationship with monthly PrEP willingness to use, ranking third in importance, suggesting that individuals who expressed willingness but had not accessed PrEP might prefer other PrEP options. Although this same negative association existed in mainland China, its influence was weaker, ranking 15th in importance. Conversely, willingness to use two-monthly injectable PrEP showed a negative association in both mainland China and Hong Kong but ranked third in mainland China and only reached 12th in Hong Kong.

Age exhibited distinct patterns in its influence. In Hong Kong, it showed a weak negative relationship with willingness to use monthly PrEP, suggesting younger participants were more receptive to this option. In contrast, mainland China showed a weak positive association, indicating slightly higher acceptance among older participants.

Variations were further exemplified by the factor heard about on-demand PrEP, which showed a positive association with monthly PrEP use willingness in Hong Kong, suggesting that awareness of different PrEP options might increase openness to monthly PrEP. This factor did not emerge as a key influence in mainland China.

Two-monthly injectable PrEP

As shown in Fig. 6, in Hong Kong, willingness to use six-monthly injectable PrEP emerged as the most influential factor, showing a negative relationship with the outcome, indicating that individuals not willing to use six-monthly injectable PrEP options were more inclined to consider two-monthly injectable PrEP. Similarly, willingness to use implant PrEP and willingness to use monthly oral PrEP both exhibited negative associations, ranking second and third, respectively, suggesting a preference pattern where willingness to use implant or monthly oral PrEP might decrease willingness to use two-monthly injectable options. These relationships remained consistent in mainland China, where these factors ranked first, second, and fourth in importance, highlighting a shared pattern in how preferences for different PrEP intervals interacted.

Distinctions emerged in other factors’ influences. In mainland China, willingness to use daily PrEP exhibited a negative relationship with willingness to use two-monthly injectable PrEP, ranking 13th in importance, suggesting that those less willing in daily PrEP use might find the two-monthly PrEP more appealing. This factor did not appear among the key influences in Hong Kong. Additionally, heard two-monthly injectable PrEP showed a negative association with two-monthly injectable PrEP use willingness in Hong Kong, suggesting that awareness of this option might decrease willingness for its use, while this factor did not emerge in the mainland China analysis.

Six-monthly injectable PrEP

As shown in Fig. 7, in Hong Kong, willingness to use two-monthly injectable PrEP exhibited a negative relationship with the outcome, ranking first in importance, indicating that individuals willing to two-monthly injectable PrEP might be less inclined to consider six-monthly injectable options. Similarly, willingness to use monthly oral PrEP showed a negative association, ranking ninth, suggesting that preferences for monthly oral PrEP options might decrease willingness in six-monthly injectable PrEP use. These patterns were mirrored in mainland China, where these factors ranked second and fifth, respectively, highlighting consistent trends in how preferences for different PrEP options interacted.

Variations emerged in several key factors. In Hong Kong, speaking to a doctor about starting PrEP exhibited a negative relationship with six-monthly injectable PrEP use willingness, ranking 12th in importance, suggesting that individuals who had discussed PrEP with healthcare providers did not prefer six-monthly injectable PrEP use. This factor did not emerge in mainland China, indicating potential differences in how healthcare provider interactions influenced PrEP preferences.

The analysis also revealed willingness patterns in behavioural and attitudinal factors. In Hong Kong, the frequency of condom use during vaginal sex in the past 6 months showed a positive association with injectable PrEP use willingness, ranking third, indicating that individuals with higher condom use might be more open to this PrEP option. While this factor maintained a positive relationship in mainland China, ranking eighth. Additionally, reluctance to use PrEP exhibited a positive association in Hong Kong, ranking 15th, suggesting that those initially resistant to PrEP might be more receptive to the six-monthly injectable option, though this factor was not prominent in mainland China.

Mainland China showed unique patterns, with a willingness to use daily PrEP displaying a positive relationship with six-monthly injectable PrEP use willingness, ranking sixth in importance. This suggested that individuals open to daily oral PrEP might also be receptive to six-monthly injectable options, a pattern not prominently observed in Hong Kong.

Implant PrEP

As shown in Fig. 8, in mainland China, willingness to use six-monthly injectable PrEP emerged as the most influential factor, showing a negative relationship with the outcome, indicating that individuals’ willingness to use six-monthly injectable PrEP options might be less inclined to consider long-term implants. Similarly, willingness to use two-monthly injectable PrEP exhibited a negative association, ranking second in importance, suggesting that preferences for a shorter two-monthly option might decrease openness to implant options. These relationships maintained consistency in Hong Kong, where these factors ranked third and first, respectively, highlighting shared patterns in how preferences for different PrEP intervals interacted with willingness to use implants.

Distinctions emerged in the influence of daily PrEP preferences. In mainland China, willingness to use daily PrEP exhibited a positive relationship with willingness to use 1-year implant PrEP, ranking fourth in importance, suggesting that individuals open to daily PrEP might also be receptive to long-term implant options. This factor was not among the key influences in Hong Kong.

Discussion

This study applied machine learning techniques to identify and compare factors influencing preferences for PrEP options among MSM in mainland China and Hong Kong. Our findings reveal that while preferences varied, oral PrEP remains the preferred choice over non-oral options in both locations, with 55.7% (53.3–58.1%) of mainland Chinese and 48.1% (43.9–52.3%) of Hong Kong participants expressing willingness to use on-demand oral PrEP (P < 0.01). These preferences are influenced by distinct combinations of demographic, behavioural, and social factors, providing new insights for tailoring HIV prevention strategies to local contexts.

The preference for oral PrEP aligns with previous research indicating greater acceptability of oral PrEP, possibly due to its perceived flexibility, efficacy, and reversibility.5,18,33,34 However, oral PrEP usage in mainland China among MSM remains below 1%,35 despite efforts by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, academic researchers, and community-based organisations to introduce and scale up PrEP programs. This low uptake reflects multiple barriers. Stigma is a persistent issue. HIV-related stigma and fears of being identified as gay or promiscuous discourage MSM from accessing PrEP services, particularly in settings where same-sex behaviour remains highly stigmatised.36 Awareness of PrEP remains limited. A 2018 survey in China found that only 57% of MSM had heard of PrEP.36 Accessibility is also a concern. Before the patent expiry, Truvada was costly and only sporadically available in formal healthcare channels, with many users resorting to informal online purchases, raising issues of safety and continuity.37–40 Additionally, MSM generally showed a preference for on-demand or long-acting oral PrEP over injectable or implant options. The relatively lower willingness to use non-oral PrEP (e.g. two-monthly injectable PrEP: 21.1% [19.1–23.1%] in mainland China, 15.4% [12.3–18.5%] in Hong Kong) may reflect concerns about long-term commitment, injection anxiety, or limited familiarity with newer options.41 However, individuals willing to use six-monthly injections were often unwilling to use two-monthly injections, and vice versa. These findings highlight the complexity and suggest a diversity of preferences in mainland China and Hong Kong. Although campaigns to promote injectable PrEP are ongoing, it is crucial to also support current oral products to meet existing needs. Addressing concerns about non-oral PrEP modalities may further enhance their acceptability.

Variations in factors associated with PrEP preferences highlight the importance of localised approaches. In Hong Kong, condom use frequency during vaginal sex showed strong positive associations with willingness to use various PrEP modalities, whereas this factor was less influential in mainland China. This difference may be due to differences in PrEP accessibility, public awareness, and HIV prevention strategies. In Hong Kong, greater exposure to PrEP-related information may lead individuals to align their decisions more closely with their sexual behaviour, whereas, in mainland China, limited awareness of and access to PrEP may reduce the influence of condom use on PrEP decisions. Additionally, in Hong Kong, migrants show a stronger preference for daily PrEP than locals, unlike in mainland China, where birth location has little effect on daily PrEP choices. This suggests that migration status may influence PrEP decision-making differently. Studies indicate that migrant MSM are more likely to engage in sexual risk behaviours, report additional barriers to accessing PrEP,42 have less access to HIV/STI testing services,43 and show greater willingness to use PrEP.44 Given no significant difference in efficacy between on-demand and daily PrEP strategies, the effectiveness of program implementation solely relies on individual preferences and sexual behaviour patterns.45 These distinctions emphasise the need for specific strategies in PrEP implementation.

The role of social networks and healthcare engagement varied between mainland China and Hong Kong. In mainland China, the presence of friends using PrEP positively influenced individuals’ willingness to adopt daily PrEP, which aligned with findings in Western and other Asian settings where peer influence could foster social acceptance and increased uptake.46–48 However, the negative association observed in Hong Kong reveals complex cultural and societal dynamics that distinctly shape PrEP perceptions. Studies indicate that MSM in Hong Kong, where discussions on HIV prevention remain highly sensitive, prefer to receive PrEP-related information privately.49,50 This issue may stem from Hong Kong’s densely populated environment and tightly interconnected social circles, where concerns about confidentiality and reputation influence individuals’ healthcare decisions.51,52 In contrast, MSM in mainland China, where PrEP discussions are still emerging, may rely more on peer influence as a primary source of information and support.49,50 This finding might be attributed to several intersecting sociocultural factors. Within Hong Kong’s densely populated environment, characterised by closely interconnected social networks and a pronounced emphasis on personal privacy, individuals often demonstrate heightened sensitivity regarding health-related discussions, particularly concerning HIV prevention and treatment methods.51,52 The intimate nature of these tightly knit social circles, combined with strong cultural values surrounding privacy maintenance, may create an environment where concerns about confidentiality and reputation preservation significantly influence healthcare decisions. Similarly, healthcare provider discussions showed different impacts, with Hong Kong residents who had discussed PrEP with doctors showing less willingness to use injectable options. Discussing with healthcare providers may dissuade MSM from accessing six-monthly injectable PrEP. This trend may be attributed to the cautious stance of healthcare providers in Hong Kong regarding long-acting PrEP, potentially due to limited local clinical experiences and PrEP programs with injectable options.7 Additionally, MSM in Hong Kong may place greater trust in medical advice, and doctors may be more likely to recommend daily oral PrEP due to its well-documented efficacy and established use.7,53,54 Additional training for healthcare providers is necessary to ensure that MSM receive the information that they need to access different types of PrEP and increase uptake and adherence. These findings suggest that peer influence and healthcare guidance operate differently in each context, necessitating tailored approaches to social support and medical counselling.

The use of the random forest classifier, one machine learning approach, provided new insights into PrEP preferences that may have been otherwise lost when using traditional statistical analysis. Through the use of SHAP values, we could identify complex interactions between demographic, behavioural, and social factors and identify patterns in PrEP use. Compared to the more conventional regression-based analyses that presume linearity, machine learning approaches allowed for a more robust and flexible exploration of predictors, such as detecting non-linear patterns and subgroup-level trends. The other strengths of this study include its large sample size (n = 2142) and sophisticated analytical approach using SHAP values to identify key predictive factors. However, our study has several limitations. Although online recruitment methods are effective for reaching large, geographically dispersed populations, this approach limits conclusions about causality, and the reliance on online convenience sampling may affect the sample’s overall representativeness. People who take part in online surveys may differ from those who do not participate in terms of their willingness and ability to disclose private behaviours. Furthermore, the self-reported nature of the information poses risks of recall bias and social desirability bias, as the individuals would tend to underreport or overreport conduct based on what they believe is socially acceptable to align with perceived social norms,55,56 which may affect the accuracy of the findings. Additionally, inherent limitations of the machine learning model itself should be considered, including potential overfitting, model uncertainty in predictions, and complex algorithms that may limit the interpretability of specific decision paths. The model’s performance metrics, while strong, still indicate some degree of prediction error that suggests caution when applying findings to real-world scenarios.

In conclusion, although oral PrEP remains the preferred choice among MSM in both mainland China and Hong Kong, the factors influencing PrEP preferences differ. Enhanced education about newer PrEP modalities, combined with targeted support through both peer networks and healthcare providers, may help optimise PrEP implementation across these diverse settings.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data availability

The data that support this study cannot be publicly shared due to ethical or privacy reasons and may be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author if appropriate.

Conflicts of interest

Weiming Tang, Edmond Pui Hang Choi, Nittaya Phanuphak, Benjamin Bavinton and Lei Zhang are Associate Editors, and Jason Ong is co-Editor-in-Chief for Sexual Health but were not involved in the peer review or decision-making process for this paper.

Declaration of funding

JJO is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Emerging Leadership Fellowship (Grant number: 1193955). LZ is supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China (2022YFC2304900, 2022YFC2505100), the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC2505100, 2022YFC2505103); Outstanding Young Scholars Support Program (Grant number: 3111500001); Epidemiology modelling and risk assessment (Grant number: 20200344), and Xi’an Jiaotong University Young Scholar Support Grant (Grant number: YX6J004).

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants who took part in our study. This study would not have been possible without the many collaborators who assisted across the region: AIDS Concern (Andrew Chidgey, KL Lee); Alegra Wolter; APCOM Foundation (Vaness S. Kongsakul); Asia Pacific Council of AIDS Service Organizations (Martin Choo); Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health and Society (Adam Hill); Bali Medika (Yogi Prasetia); Blue Diamond Society (Manisha Dhakal); Community Health and Inclusion Association (Viengkhone Souriyo); FHI 360 (Amornrat Arunmanakul, Chris Obermeyer, Htun Linn Oo, Keo Vannak, Linn Htet, Lucyan Umboh, Mario Chen, Matthew Avery, Mo Hoang, Ngo Menghak, Nicha Rongram, Oudone Souphavanh, Phal Sophat, Rajesh Khanal, Sanya Umasa, Stacey Succop, Stanley Roy Carrascal, Stephen Mills, Sumita Taneja, Tinh Tran, Vangxay Phonelameuang); Grindr For Equality; Institute of HIV Research and Innovation (Rena Jamamnuaysook and the Tangerine Clinic staff); Kirby Institute (Andrew Grulich, Benjamin Hegarty, Huei-Jiuan Wu, Jeff Jin, Ye Zhang); KLASS (Andrew Tan Tze Tho, Samual Lau), Malaysian AIDS Council (Davindren Tharmalingam); Myanmar Youth Stars (Min Thet Phyo San); National Association of People with HIV Australia/Living Positive Victoria (Beau Newham); PATH (Asha Hegde, Bao Vu Ngoc, Davina Canagasabey, Ha Nguyen, Hong An Doan, Irene Siriait, Irma Anintya Tasya, Kannan Mariyapan, Khin Zarli Aye, Kyawzin Thann, Phan Thai, Phillips Loh, Phuong Quynh, Saravanamurthy Sakthivel, Tham Tran); Queer Lapis (Azzad Mahdzir); Sisters Foundation (Thitiyanun (Doy) Nakpor); Taipei City Hospital (Stephane Ku); Tingug-CDO Inc (Reynate Pacheco Namocatcat); UNAIDS Country Offices for Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, The Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam (especially Guo Wei, Komal Badal, Patricia Ongpin, Polin Ung, Weng Huiling); the Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific; University of North Carolina Project-China (Jie Fan, Long Ren, Rayner Kay Jin Tan); Youth Lead (Jeremy Fok Jun Tan); WHO Country Offices for Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, The Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam; the WHO South East Asia Regional Office; and WHO Western Pacific Regional Office.

References

1 UNAIDS. UNAIDS data 2022: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2022. Available at https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2023/2022_unaids_data

2 UNAIDS. 2024 global AIDS report — The Urgency of Now: AIDS at a Crossroads: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2024. Available at https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2024/global-aids-update-2024

3 Yan L, Yan Z, Wilson E, Arayasirikul S, Lin J, Yan H, et al. Awareness and willingness to use HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) among trans women in China: a community-based survey. AIDS Behav 2021; 25(3): 866-74.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

4 Beyrer C, Baral SD, Collins C, Richardson ET, Sullivan PS, Sanchez J, et al. The global response to HIV in men who have sex with men. The Lancet 2016; 388(10040): 198-206.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

5 Centre of Health Protection. Guidance on the use of HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in Hong Kong. Scientific Committee on AIDS and STI (SCAS), Centre for Health Protection, Department of Health; 2022. Available at https://www.aids.gov.hk/english/publications/pubsearch_1.html

6 Hong Kong Advisory Council on AIDS. Recommended HIV/AIDS Strategies for Hong Kong (2022–2027); 2022. Available at https://www.aca.gov.hk/english/strategies/hk_strategies.html

7 Wong NS, Chan DP, Kwan TH, Lui GC, Lee KC, Lee SS. Dynamicity of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis usage pattern and association with executed adherence in MSM: an implementation study in Hong Kong. AIDS Behav 2024; 28(4): 1327-44.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

8 Wang X, Xu J, Wu Z. A pilot program of pre-exposure and post-exposure prophylaxis promotion among men who have sex with men – 7 Study Sites, China, 2018–2019. China CDC Wkly 2020; 2(48): 917-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

9 Wang H, Wang Z, Huang X, Chen Y, Wang H, Cui S, et al. Association of HIV prophylaxis use with HIV incidence in men who have sex with men in China: a nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Network Open 2022; 5(2): e2148782.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

10 Fu Y, Ashuro AA, Feng X, Wang T, Zhang S, Ye D, et al. Willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and associated factors among men who have sex with men in Liuzhou, China. AIDS Res Ther 2021; 18: 46.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

11 Luo S, Wang Z, Lau JT-F. The general public’s support toward governmental provision of free/subsidized HIV preexposure prophylaxis to at-risk Chinese people: a population-based study. Sex Transm Dis 2021; 48(3): 189-94.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

12 Choi EPH, Wu C, Choi KWY, Chau PH, Wan EYF, Wong WCW, et al. Ehealth interactive intervention in promoting safer sex among men who have sex with men. npj Digit Med 2024; 7(1): 313.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

13 Department of Health – HIV Testing Service. Prevention – Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Available at https://www.hivtest.gov.hk/en/hiv_prevention_and_condom_use/PrEP.html

14 Lin C, Li L, Liu J, Fu X, Chen J, Cao W, et al. HIV PrEP services for MSM in China: a mixed-methods study. AIDS Care 2022; 34(3): 310-4.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

15 Kwan TH. Social and genetic network analyses for assessing the HIV transmission dynamics in the men who have sex with men community in Hong Kong. PhD thesis, The Chinese University of Hong Kong (Hong Kong); 2019. Available at https://www.proquest.com/docview/2375494504

16 Kwan TH, Lee SS. Bridging awareness and acceptance of pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men and the need for targeting chemsex and HIV testing: cross-sectional survey. JMIR Publ Health Surveill 2019; 5(3): e13083.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

17 Sun Z, Gu Q, Dai Y, Zou H, Agins B, Chen Q, et al. Increasing awareness of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and willingness to use HIV PrEP among men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of global data. J Int AIDS Soc 2022; 25(3): e25883.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

19 Liegeon G, Ghosn J. Long-acting injectable cabotegravir for PrEP: a game-changer in HIV prevention? HIV Med 2023; 24(6): 653-63.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

20 ViiV Healthcare. Cabotegravir PrEP Worldwide Registration 2024. Available at https://viivhealthcare.com/content/dam/cf-viiv/viivhealthcare/en_GB/pdf/wwrs-for-external-use.pdf

21 Médecins Sans Frontières. Q&A on long-acting cabotegravir (CAB-LA) for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Available at https://reliefweb.int/report/world/qa-long-acting-cabotegravir-cab-la-pre-exposure-prophylaxis-prep

22 Bisaso KR, Anguzu GT, Karungi SA, Kiragga A, Castelnuovo B. A survey of machine learning applications in HIV clinical research and care. Comput Biol Med 2017; 91: 366-71.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

23 Belete DM, Huchaiah MD. Grid search in hyperparameter optimization of machine learning models for prediction of HIV/AIDS test results. Int J Comput Appl 2022; 44(9): 875-86.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

24 Auerbach JD, Parkhurst JO, Cáceres CF. Addressing social drivers of HIV/AIDS for the long-term response: conceptual and methodological considerations. Glob Publ Health 2011; 6(suppl 3): S293-309.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

25 HIV Modelling Consortium Treatment as Prevention Editorial Writing Group. HIV treatment as prevention: models, data, and questions—towards evidence-based decision-making. PLoS Med 2012; 9(7): e1001259.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

26 Liu Y, Xian Y, Liu X, Cheng Z, Wei S, Wang J, et al. Significant insights from a National survey in China: PrEP awareness, willingness, uptake, and adherence among YMSM students. BMC Publ Health 2024; 24(1): 1009.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

27 Zarwell M, Patton A, Gunn LH, Benziger A, Witt B, Robinson PA, Terrell DF. PrEP awareness, willingness, and likelihood to use future HIV prevention methods among undergraduate college students in an ending the HIV epidemic jurisdiction. J Am Coll Health 2025; 73(2): 700-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

28 Couronné R, Probst P, Boulesteix AL. Random forest versus logistic regression: a large-scale benchmark experiment. BMC Bioinformat 2018; 19(1): 270.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

29 Aria M, Cuccurullo C, Gnasso A. A comparison among interpretative proposals for Random Forests. Mach Learning Appl 2021; 6: 100094.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

31 Breiman L. Random Forests. Mach Learn 2001; 45: 5-32.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

32 Heuillet A, Couthouis F, Díaz-Rodríguez N. Collective explainable AI: explaining cooperative strategies and agent contribution in multiagent reinforcement learning with shapley values. IEEE Computat Intellig Magaz 2022; 17(1): 59-71.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

33 Hill-Rorie J, Biello KB, Quint M, Johnson B, Elopre L, Johnson K, et al. Weighing the options: which PrEP (Pre-exposure Prophylaxis) modality attributes influence choice for young gay and bisexual men in the United States? AIDS Behav 2024; 28(9): 2970-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

34 Han J, Bouey JZ, Wang L, Mi G, Chen Z, He Y, et al. PrEP uptake preferences among men who have sex with men in China: results from a National Internet Survey. J Int AIDS Soc 2019; 22(2): e25242.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

35 Liu Y, Wei S, Cheng Z, Xian Y, Liu X, Yang J, et al. Correlates of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis cessation among men who have sex with men in China: implications from a nationally quantitative and qualitative study. BMC Publ Health 2024; 24(1): 1765.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

36 Si M, Su X, Yan L, Jiang Y, Liu Y, Wei C, et al. Barriers and facilitators in pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use intention among Chinese homosexual men. Glob Health J 2020; 4(3): 79-86.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

37 Sha Y, Li C, Xiong Y, Hazra A, Lio J, Jiang I, et al. Co-creation using crowdsourcing to promote PrEP adherence in China: study protocol for a stepped-wedge randomized controlled trial. BMC Publ Health 2022; 22(1): 1697.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

38 Li C, Xiong Y, Muessig KE, Tang W, Huang H, Mu T, et al. Community-engaged mHealth intervention to increase uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in China: study protocol for a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2022; 12(5): e055899.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

39 Xu J, Tang W, Zhang F, Shang H. PrEP in China: choices are ahead. Lancet HIV 2020; 7(3): e155-7.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

40 Jiang Z, Wang Q, Liang J, Gu Y, Han Z, Li J, et al. Exploration of PrEP/PEP service delivery model in China: a pilot in eastern, central and western region. Glob Health Med 2024; 6(5): 295-303.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

41 Da Silva-Brandao RR, Ianni AMZ. Exploring the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) risk rituals: individualisation, uncertainty and social iatrogenesis. Health Risk Soc 2024; 26(1–2): 19-36.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

42 Tieosapjaroen W, Zhang Y, Fairley CK, Zhang L, Chow EPF, Phillips TR, et al. Improving access to oral pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV among international migrant populations. Lancet Publ Health 2023; 8(8): e651-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

43 Wu J, Wu H, Li P, Lu C. HIV/STIs risks between migrant MSM and local MSM: a cross-sectional comparison study in China. PeerJ 2016; 4: e2169.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

44 Sun S, Yang C, Zaller N, Zhang Z, Zhang H, Operario D. PrEP willingness and adherence self-efficacy among men who have sex with men with recent condomless anal sex in Urban China. AIDS Behav 2021; 25(11): 3482-93.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

45 Kwan TH, Lui GCY, Lam TTN, Lee KCK, Wong NS, Chan DPC, et al. Comparison between daily and on-demand PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) regimen in covering condomless anal intercourse for men who have sex with men in Hong Kong: a randomized, controlled, open-label, crossover trial. J Int AIDS Soc 2021; 24(9): e25795.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

46 Dubov A, Altice FL, Fraenkel L. An information–motivation–behavioral skills model of PrEP uptake. AIDS Behav 2018; 22(11): 3603-16.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

47 Santos LAD, Grangeiro A, Couto MT. HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men: peer communication, engagement and social networks. Cien Saude Colet 2022; 27(10): 3923-37.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

48 Tao J, Parent H, Karki I, Martin H, Marshall SA, Kapadia J, et al. Perspectives on a peer-driven intervention to promote pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake among men who have sex with men in southern New England: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2024; 24: 1023.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

49 Du J, Wang S, Zhang H, Liu T, Sun S, Yang C, et al. Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) awareness and engagement among MSM at high risk of HIV infection in China: a multi-city cross-sectional survey. AIDS Behav 2025; 29: 1629-39.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

50 Hao C, Lau JTF, Zhao X, Yang H, Huan X, Yan H, et al. Associations between perceived characteristics of the peer social network involving significant others and risk of HIV transmission among men who have sex with men in China. AIDS Behav 2014; 18(1): 99-110.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

51 Suen YT, Chidgey A. Disruption of HIV service provision and response in Hong Kong during COVID-19: issues of privacy and space. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2021; 20: 23259582211059588.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

52 Lau JYC, Wong N-S, Lee KCK, Kwan T-H, Lui GCY, Chan DPC, et al. What makes an optimal delivery for PrEP against HIV: a qualitative study in MSM. Int J STD AIDS 2022; 33(4): 322-9.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

53 Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, Buchbinder S, Lama JR, Guanira JV, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4(151): 151ra25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

54 Philpot SP, Murphy D, Chan C, Haire B, Fraser D, Grulich AE, et al. Switching to non-daily pre-exposure prophylaxis among gay and bisexual men in Australia: implications for improving knowledge, safety, and uptake. Sex Res Social Policy 2022; 19(4): 1979-88.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

55 Teh WL, Abdin E, P.V. A, Siva Kumar FD, Roystonn K, Wang P, et al. Measuring social desirability bias in a multi-ethnic cohort sample: its relationship with self-reported physical activity, dietary habits, and factor structure. BMC Publ Health 2023; 23(1): 415.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

56 Adams SA, Matthews CE, Ebbeling CB, Moore CG, Cunningham JE, Fulton J, et al. The effect of social desirability and social approval on self-reports of physical activity. Am J Epidemiol 2005; 161(4): 389-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |