Science meets the taipan: the discovery and description of an iconic venomous snake

Kevin Markwell A and Richard Shine

A and Richard Shine  B *

B *

A

B

Abstract

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this publication contains images of deceased persons, and discussion of historical events which may be deemed culturally sensitive.

Reflecting its large size and potent venom, the coastal taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus) from northern Australia has been the subject of several books and popular articles but published accounts of the species’ discovery and classification by Western scientists contain numerous errors and omissions. Based on examination of original specimens and historical documents, we summarise the circumstances in which the first specimens of taipans were collected and we tease out the multiple mistakes that delayed adoption of the scientific and vernacular names currently used for the species. Our analysis identifies both answers and knowledge gaps about issues such as who collected the first specimens, why errors were made in identifying and naming this massive snake, the pathways through which errors and assumptions were perpetuated, and a lack of recognition for First Nations collectors who played important roles in the capture of at least two of the first three taipans known to Australian science.

Keywords: Aboriginal, Amalie Dietrich, Donald Thomson, Elapidae, Eric Worrell, Friday Wilson, herpetological history, James Roy Kinghorn, Pseudechis scutellatus, Pseudechis wilesmithii, Tommy Tucker, William McLennan.

Introduction

More than four thousand species of snakes are known to science, with new species being named every month (based on The Reptile Database: Uetz and Freed 2025). The vast majority of snake taxa are small species that are poorly known scientifically; indeed, a recent search of databases for ecological research reported that many snake species have not had even a single paper written about their ecology (Shine 2025). At the other extreme, however, a small number of snake species attract intense attention not only from scientists, but also from the general public. The snake species most frequently studied by scientists are relatively small, abundant and non-venomous (such as European grass snakes (Natrix natrix) and American gartersnakes (Thamnophis spp.): Shine 2025), whereas the species that are best-known to the general public are those perceived to be dangerous to humans either because of large body size (such as anacondas, Eunectes spp.) or toxic venom (such as rattlesnakes, Crotalus spp.).

Although venomous species of the family Elapidae dominate the snake fauna over much of Australia, most elapids are small and pose no threat to humans. Of the larger species, arguably the most iconic is the coastal taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus; herein also referred to as ‘the taipan’). That high profile is attested to by the fact that this species has been the subject of five ‘popular’ books plus chapters in five other books (Table 1). Apart from children’s books featuring pythons (Pender 1967; Cannon 1997; Frazel 2012; MacDonald Baldwin 2003), most other books about specific taxa of Australian snakes have focused almost entirely on husbandry issues (e.g. Kortlang and Green 2001; Mutton and Julander 2011; Bedford 2024). In addition, the coastal taipan occupies an important place in the life stories of at least four celebrated Australian snake experts: Donald Thomson (1901–1970), David Fleay (1907–1993), Ram Chandra (1921–1988) and Eric Worrell (1924–1987). The species is also the co-protagonist in one of the most well-known and tragic stories in Australian herpetology involving the death of 20-year-old Sydney snake enthusiast Kevin Budden in 1950 (see Seal 1999; Markwell and Cushing 2010; Murray 2017). This event has taken on an almost mythological status in Australian herpetological history.

| Book title | Chapter/section title | Author/s | Year of publication | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Search for the Taipan, The Story of Ram Chandra | – | Phillip Jones | 1977 | |

| Traveller Brown, The Story of Ram Chandra and the Taipan | – | Tasman Beattie and Nan Rogers | 1988 | |

| The Taipan, The World’s Most Dangerous Snake | – | Paul Masci and Phillip Kendall | 1995 | |

| Ram: The Man, the Legend | – | Nan Rogers | 1999 | |

| Stalking the Plumed Serpent | Coastal taipans: a dream realised | D. Bruce Means | 2008 | |

| Venom, The Heroic Search for Australia’s Deadliest Snake | – | Brendan James Murray | 2017 | |

| Song of the Snake | The taipan, killer of the cane fields | Eric Worrell | 1958 | |

| Talking of Animals | Living with taipans | David Fleay | 1956 | |

| Living with Animals | A taipan is domesticated | David Fleay | 1960 | |

| Australian Snake Man, The Story of Eric Worrell | The deadly taipan | Roy Norry | 1966 | |

| Looking at Animals | Taipan facts and fancies The tragedy of ‘Alexandra’ the Taipan | David Fleay | 1981 | |

| The Snakebite Survivors’ Club | Chapter 3 Australia Chapter 6 Australia Chapter 9 Australia | Jeremy Seal | 1999 | |

| Snake Bitten, Eric Worrell and the Australian Reptile Park | Quest for the Taipan | Kevin Markwell and Nancy Cushing | 2010 |

The taipan’s high public profile is further evident in the name of a national basketball team (the Cairns Taipans), a fighter aircraft (AC-88 Taipan), an Australian Army helicopter (MRH Taipan), rides at two Australian theme parks (Steel Taipan at Queensland’s Dreamworld and The Taipan at Jamberoo Park, New South Wales), a song by the Australian rock band, Cold Chisel (Taipan) as well as a range of product brands including a herbicide, fishing rods and computer equipment. Markwell and Cushing (2016) examined the various meanings that have been constructed for the species through the social structures and practices embedded within Australian popular culture.

This intense public interest in the taipan, and the consequent array of publications about the species, provide a unique opportunity to explore not only how venomous snakes are portrayed to the public, but also how ‘popular’ writers recount the attempts of scientists to capture and understand these formidable animals. We might expect, for example, that the history of early encounters between colonial scientists and taipans would be well-known and clearly documented; but in the process of investigating those reports we encountered contradictions, errors and gaps in knowledge. To fill in some of those gaps we examined primary sources such as historical reports as well as diaries and correspondence of early scientists and inspected most available specimens of taipans collected early in the history of scientific exploration of Australia and New Guinea.

The timeframe for our examination commences with the year the first taipan was collected for science in 1866 and concludes at the end of the 1930s, after taxonomic and nomenclatural confusion had been resolved. Our aim is to clarify scientific involvement with the taipan in the 70 years following its discovery by Western biologists.

The coastal taipan (Oxyuranus scutellatus)

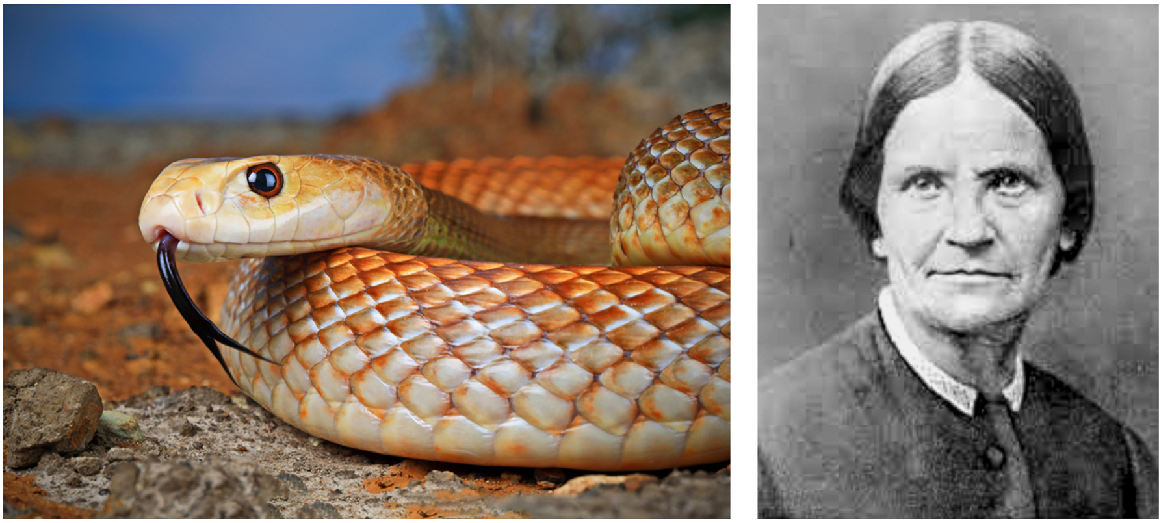

The coastal taipan is a large dangerously venomous elapid snake that occurs along the east coast of Australia from Cape York Peninsula (Queensland) down to around Grafton on the far north coast of New South Wales as well as along the northern Australian coast from the Kimberley region in Western Australia to the northern part of the Northern Territory (Cogger 2014). It is a slender snake with glossy scales, usually brown dorsally and white ventrally (Fig. 1). These snakes attain an average adult length of around 2 m, although specimens of almost 3 m are known (see, for example, Beatson 2020). Distinctive features include a long, narrow head (sometimes evocatively described as ‘coffin-shaped’) and weakly keeled dorsal scales which occur in 21–23 rows across the snake’s mid-body. The anal scale is undivided whereas the subcaudal scales (beneath the tail) are divided.

The coastal taipan, Oxyuranus scutellatus (photograph by Rob Valentic) and the woman who obtained the first specimen known to Western science, Amalie Dietrich (from Sumner 1983).

Unlike most other Australian elapids, taipans prey almost entirely on mammals such as rats and small marsupials (Shine and Covacevich 1983). As with the majority of tropical terrestrial snake species, taipans are oviparous, producing clutches of up to 20 eggs (Worrell 1963; Shine and Covacevich 1983; Cogger 2014). The species can deliver a large quantity of venom which contains powerful neurotoxins as well as at least two procoagulants (Mirtschin et al. 2017; Tasoulis et al. 2020). Until a specific antivenom was developed in 1955, the bite of this species was almost always fatal to humans. In New Guinea, coastal taipans are responsible for 70–80% of the 1000 or so snakebite deaths per annum (PNG Snakebite Research Project undated).

The genus Oxyuranus also contains two other species. The type specimen of the inland taipan (Oxyuranus microlepidotus) was described as Pseudechis microlepidotus by McCoy in 1879, and later renamed Parademansia microlepidotus by Kinghorn in 1955 and as Pseudechis ferox by Macleay (1882). This inland species occurs in south-western Queensland, the north-western corner of New South Wales, the north-eastern corner of South Australia and the south-eastern corner of the Northern Territory (Wilson and Swan 2025). Covacevich et al. (1981) and Cogger (1983) recognised the species as belonging to Oxyuranus rather than the separate genus Parademansia. Another species in the genus, the western desert taipan (O. temporalis), was described in 2007 (Doughty et al. 2007). This species appears to be widespread but seemingly rare across the western deserts of central Australia (Shea 2007; Brennan et al. 2012; Cogger 2014; Black et al. 2020).

Attitudes to snakes in colonial Australia

To put the history of Western science’s early interactions with taipans into perspective, we first need to consider broader views of snakes at the time of those discoveries. In that respect, there is a clear dichotomy between the traditional owners of the land (First Nations people) and the colonising British. For many First Nations communities of Australia, snakes play a central role in mythology. The Rainbow Serpent is a powerful being associated with acts of creation and destruction (Taçon et al. 1996). The Rainbow Serpent is an integral part of the Creation and Dreamtime stories of those First Nations, is frequently depicted in Aboriginal art, and is known by a variety of names and through different totemic appearances across the First Nations language groups of Australia (Morris and Morris 1965; Japingka Aboriginal Art undated). Snakes also play an important role as traditional food (‘bush tucker’) of First Nations people, particularly in tropical Australia where pythons (Antaresia, Aspidites, Liasis, Morelia) and filesnakes (Acrochordus arafurae) are still eaten (e.g. Shine 1991). Venomous snakes such as the coastal taipan, the subject of our paper, were greatly feared by many First Nations communities (Thomson 1933).

British colonists brought with them a different set of beliefs about snakes. Within Judaeo-Christian mythology, the serpent persuaded Eve to eat fruit from the tree of knowledge, which she then shared with Adam, leading to their expulsion from the Garden of Eden (Lunney and Ayers 1993). Most of the British settling Australia had little direct experience of snakes, because only three species of snakes occur in the British Isles. Some early encounters with deadly snakes in the Sydney district including common death adders (Acanthophis antarcticus), eastern brownsnakes (Pseudonaja textilis) and tigersnakes (Notechis scutatus) would have led to human fatalities, although death from snakebite in the first decades of the New South Wales colony was an ‘apparently rare occurrence’ and snakes were not seen as a significant threat (Hobbins 2017: p. 25).

A substantial shift away from that relaxed attitude occurred by the beginning of the 1800s. Increasingly, Australian snakes were portrayed as ‘highly poisonous … both within the colony and in European natural history texts’ (Hobbins 2017: p. 26). Indeed, in 1820, an anonymously authored piece in the Sydney Gazette warned newcomers to New South Wales that the colony had an abundance of snakes ‘of different kinds and adders, all venomous, their bite is fatal, unless remedies are used without delay’ (An Australian 1820: p. 3). Various remedies (the use of ‘snake oil’, application of a ligature and cutting the bite site) are helpfully suggested by the author. Newspaper reports of the deaths of dogs, livestock and sometimes people, as well as the writings of explorers and naturalists, helped fuel the public perception that snakes were a dangerous menace. Such attitudes are detectable in Australian popular culture from the late 1800s. For example, the snake appears as a malevolent intruder, sliding under the floorboards of a house in Henry Lawson’s short story, The Drover’s Wife (Lawson 1892). The snake represents not just a direct threat to the woman and her dog, but also the unpredictable threat that wild, untamed nature posed to those whose livelihood depended upon its domestication.

A negative and fearful attitude towards snakes permeated many forms of literature. For example, a sinister snake slithered into view as one of the characters in the much-loved children’s book, Snugglepot and Cuddlepie (Gibbs 1918). The ‘wicked Mrs Snake’ keeps company with the ‘Big, bad Banksia Men’ and is relentless in pursuit of the gumnut babies and their friend ‘Mr Lizard’. Until she was killed, Mrs Snake was an ever-present danger in the Australian bush. There is no ambiguity in Gibbs’ treatment of this serpent: ‘So Mrs Snake was tied head and tail ‘til she couldn’t move, and her wicked head was knocked off. A great shout went up, for she was very wicked and deserved to die, and everyone was glad’.

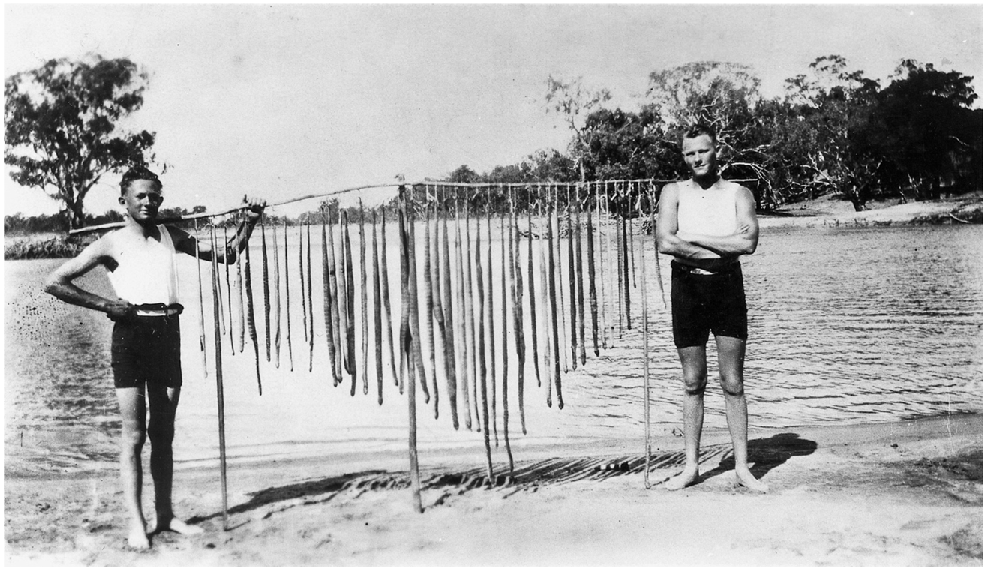

Clearly, snakes have not been celebrated as part of the fauna of Australia as have kangaroos, koalas and kookaburras. Indeed, for Australians growing up in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the dominant mantra was ‘the only good snake is a dead snake’ (see Fig. 2). As Markwell and Cushing (2010: p. xiv) noted:

… Australians prided themselves on their killing of snakes. They displayed their mangled, lifeless bodies along fences and in photographs; they had picnic days for group snake hunts in which hundreds of snakes were killed; and they read stories in which snakes were nasty, malevolent beings.

Young men posing with over 40 tigersnakes (Notechis scutatus) that they had slaughtered near the Murray River in South Australia. Photograph courtesy of the State Library of South Australia.

This collective fascination for snakes was exploited by generations of men (and some women) who made their living displaying snakes at agricultural shows and travelling circuses. In the Sydney suburb of La Perouse, the Cann family ran Sunday snake shows for many decades. These ‘snakeys’ have been well documented by Worrell (1960) and by Cann (1986, 2001, 2014). In an attempt to change the prevailing narrative, Worrell (see, for example, Worrell 1952, 1958, 1959, 1963) was one of the earliest naturalists who countered myths with facts about snake biology and behaviour. His writings emphasised that snakes were timid and shy, almost always preferring to flee from an encounter with a person. He consistently argued that reptiles (apart from dangerous snakes) should be protected because of the role they played in keeping vermin in check (Markwell 2024).

Despite sporadic attempts by experts like Worrell to challenge the antisnake orthodoxy, snakes in post-colonial Australia occupied a marginalised position within Australia’s understanding of its fauna. Snakes remained feared and even reviled up until the end of the twentieth century. Although naturalists including Charles Barrett, Vincent Serventy, David Fleay and Eric Worrell offered counter-narratives, it was not until the 1970s that snakes and other reptiles were afforded legal protection that had been given to mammals and birds decades earlier (Shine 1991, 2023). Recent years have seen increasing efforts to portray snakes in a more positive light (e.g. Shine et al. 2023; von Takach et al. 2024).

The ‘Dietrich taipan’

Accounts of the earliest European involvement with the coastal taipan have been published in a number of academic and popular forms (see for example White 1922; Kinghorn 1923a, 1923b; Thomson 1933; Jones 1977; Sumner 1993; Masci and Kendall 1995; Markwell and Cushing 2016; Murray 2017). However, our analysis has found that this early history is characterised by confusion over the snake’s taxonomy and nomenclature as well as some errors of fact.

The first coastal taipan to be brought to the notice of Western science was part of a large consignment of specimens despatched by a German-born natural history collector, Amalie Dietrich (see Fig. 1), to her employer (the Museum Godeffroy in Hamburg), arriving there in December 1866. The snake had been collected earlier in 1866 in the vicinity of Rockhampton, Queensland (Sumner 1985, 1993).

Dietrich spent nine years in Queensland, from 1863 to 1872. That timespan included a year in Rockhampton (early 1866 until early 1867), after which she departed for Mackay (Sumner 1985). Dietrich had been commissioned to collect specimens by shipping magnate, Johann Cesar VI Godeffroy, who had established the eponymously named Godeffroy Museum in Hamburg in 1861 (Sumner 1985). Following the expansion of his trading empire to include Australia and the South Seas islands, Godeffroy employed collectors to obtain natural history, geological and ethnographic specimens over several years. As a result, he amassed a significant collection for his museum and on-sold duplicates to other parties (Sumner 1985). Included in the ethnographic specimens were human skulls and skeletal material sourced from Australia and South Pacific communities. Dietrich was involved in the acquisition of Aboriginal remains although the extent and nature of her involvement remains unclear (see for example Affeldt and Hund 2019–2020; Turnbull 2019–2020).

As her biographer, Ray Sumner (1985, 1993), observed, Amelie Dietrich lived a life on the periphery. She was of working-class origins, with little formal education, and was a single mother at the time she left for Australia. Her relocation to the new British colony of Queensland, far removed from her home in Germany, resulted in social isolation, poverty, uncertainty and at times, great adversity. Yet she was a highly productive collector, making extensive collections of zoological, botanical, geological and anthropological specimens. Her contributions to botany and zoology have been recognised in her name being given to at least six species. She is attributed as the collector of 33 type specimens of plants (Sumner 1985).

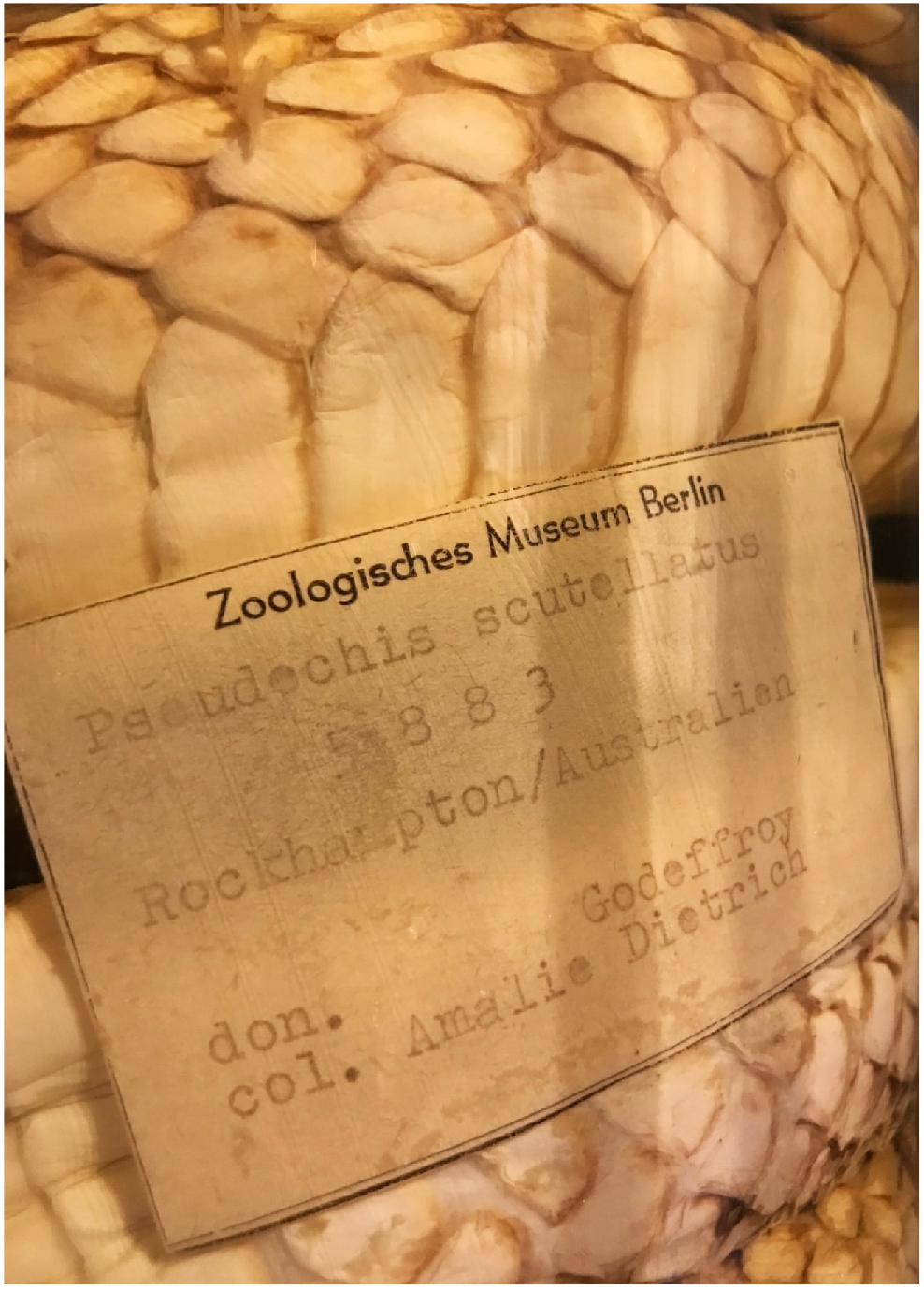

One of the zoological specimens she sent to Hamburg was a large, brown-coloured snake that had been collected when she was based in the Rockhampton area. Over the course of the following 12 months, the preserved snake came to the attention of herpetologist Wilhelm Peters who published a formal description of this giant animal in 1867 (before Dietrich returned to Europe) as Pseudechis scutellatus. Dietrich never published any scientific papers under her own name.

Who collected ‘the Dietrich taipan’?

All published narratives regarding Dietrich’s involvement with this snake state or imply that she collected the animal herself, but we could find no direct evidence to support that claim. Peters’ (1867) published description of the snake does not include any reference to Dietrich, although she is named as the collector on the identification label inserted into the jar containing the snake (see Fig. 3). However, this does not prove that Dietrich collected the snake herself.

Label showing Amalie Dietrich as the collector of the taipan holotype, from the collection in the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin. Photograph by Kevin Markwell.

The earliest published reference to Dietrich having collected the taipan is found in Phillip Jones’ (1977) book ‘Search for the Taipan, the Story of Ram Chandra’. Jones was a novelist, script-writer and radio producer who moved to the Mackay district in the late 1950s. Although his book focuses primarily on the involvement of local snake expert Ram Chandra with the taipan, he provides some background on the early history of the taipan. He states (p. 29):

It was in this vicinity [Rockhampton] that a strange, dedicated woman had captured the snake [our emphasis] which was to become known as the taipan, and in that bygone time she had dispatched it, suitably packed as a wet specimen, to a place 16,000 km distant, where it would be named as a new species by a man who until that time had never heard of Rockhampton.

Later in his book, Jones states that ‘Amalie made a huge collection in this area [Rockhampton] … she was not to know that the snake she had found near Rockhampton was one of the world’s deadliest, a killer from whose venom there was no protection and no hope of survival’ (Jones 1977: p. 62). Jones provides a translation of a paragraph of Peters’ scientific description of the species, which was originally published in German.

Jones provides no sources for his information, but in the Acknowledgements section of his book he thanks Dr John Graydon (at the time a Senior Consultant with the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories, Melbourne), whose ‘exhaustive reply to my early inquiry revealed a whole avenue of research’. Graydon, who had a long involvement in the production of Australian snake and spider antivenoms (Brogan 1990) may have provided Jones with background information concerning Dietrich. Jones also thanks the ‘Queensland Museum’, although he does not mention anyone by name. A letter in the archives of the Queensland Museum (QM) (dated 17 April 1973) shows that Peters’ description of Pseudechis scutellatus (‘Monatsberichte der Deutschen Akademie der Wissenschaften’) was provided to Jones by Jeanette Covacevich, who was employed initially as a trainee cadet at the Museum in 1966, then appointed the first curator of vertebrates at that museum the following year and later, as Senior Curator (Reptiles) in 1978. In a letter of 11 April 1973 (QM archives), Jones asks for information about whether or not the taipan specimen was collected by Amalie Dietrich herself, so he was clearly aware of the ambiguity. His question, however, went unanswered by Covacevich.

Unfortunately, none of the articles (many of them ‘tribute pieces’) on Dietrich that have been published in Australian zoological and field-naturalist journals (Turner 1933; Gilbert 1948; Mulac-Teichmann 1964; Berry 1966; Lowie 1968) mention the collection of the taipan. Gilbert (1948: p. 221) notes that Dietrich ‘gathered jungle snakes and lizards …’ but does not specifically mention the taipan. Most of these articles appear to have been based on the book written about Dietrich by her daughter, Charitas Bischoff, first published in 1909, with the first English translation published in 1931 (Bischoff 1931). This book (including letters supposedly from Dietrich to her daughter) has been demonstrated to be largely fictional by Sumner (1985). Unfortunately, Dietrich’s own papers were destroyed during the bombing of Hamburg during World War II (Sumner 1985).

Given that Peters does not mention Dietrich as the collector in his formal description of the taipan, the source of Graydon’s information (assuming it was Graydon who passed this information on to Jones) remains unknown. A search of Graydon’s papers held at the CSL Seqirus archives failed to locate any correspondence with Jones. Sumner accessed various documents (including catalogues of the Godeffroy Museum) and was able to establish an inventory of species of animals that had been sent there by Dietrich, but this information first appeared in Sumner’s (1983) paper, some 6 years after the publication of Jones’ book. Following Jones, others who have written on the coastal taipan state unequivocally that Dietrich collected the snake herself. But the only evidence for that claim is that she is named as the collector of the specimen on the label inside the jar that contains the specimen. It might well have been she who collected the snake but, alternatively, the snake could have been caught and killed by someone else and given or sold to her.

Examination of the specimen (ZMB 5883) shows that the snake had not been shot and instead had its vertebral column broken (F. Tillack, pers. comm., January 2025). This method of killing – a single blow to the forebody – suggests that whoever collected ‘the Dietrich taipan’ was skilled in killing snakes. These are formidable animals, especially at the size of the Dietrich specimen, and a high proportion of taipan specimens in museum collections are badly damaged by repeated blows and other injuries (R. Shine, pers. obs.). For example, one of the specimens obtained from a First Nations collector (Friday Wilson) by McLennan (1922) was so badly damaged that McLennan could salvage only its skull (see below). Dietrich’s primary scientific expertise was in botany, suggesting that Dietrich herself may not have collected the giant snake. Indeed, Dietrich’s biographer, Ray Sumner, said in an email to us dated 27 July 2024: ‘I can only conjecture that Dietrich did indeed purchase the specimen [of the taipan]. Her real talent was botany’.

Did somebody else kill the snake and donate or sell it to Dietrich? Obtaining specimens in this way was commonplace for early naturalists. For example, Indian surgeon and biologist Edward Nicholson wrote in 1874 (Nicholson 1874) that:

The European in India can do little himself beyond keeping a sharp look-out whilst walking for exercise or after game; by far the greater part of collections are made by employing the patience and acuteness of Indians in this laborious pursuit. In stations where a reward is given by the authorities for every cobra that is killed, other snakes will often be brought in, and an arrangement with the police will bring these to anyone willing to give a small reward. Where public money is not devoted to this philanthropic object the best way is to make generally known amongst toddy-drawers, fishermen, grass-cutters and Indian camp-followers in general, that a reward will be given for every snake that is brought in.

The species composition of reptiles that Dietrich shipped to Germany suggests that a proportion of these specimens were collected by others. For example, her collection included specimens that were identified as a thorny devil (Moloch horridus) and a perentie (Varanus giganteus), species found only in desert habitats of central Australia (Cogger 2014). Dietrich never visited that region (Sumner 1985). Likewise, she obtained and shipped representatives of several reptiles that were identified as species from southern Australia (e.g. Egernia cunninghami, Hemiergis decresiensis, Rankinia diemensis, Hoplocephalus bungaroides and Morelia spilotes spilotes) despite spending only a few days in Sydney as she transited out of the country (Sumner 1983). Although some of these animals may have been misidentified specimens collected by Dietrich in Queensland, (for instance H. bungaroides may have been a misidentified H. stephensii) it is likely that (as was true for most early collectors) Dietrich purchased or was given animals and plants from local people as well as collecting specimens herself.

Although we will probably never know who collected the specimen obtained by Amalie Dietrich in 1886, that person may well have been Aboriginal rather than European. The population of Aboriginal people around Rockhampton was estimated at 600 people in 1855, when European colonists arrived (Shield 2016) whereas the 1861 census of the area (which omitted Aboriginal people) recorded 517 people (434 men, 83 women: https://hccda.ada.edu.au/Individual_Census_Tables/QLD/1861/census/). As well as outnumbering Europeans, First Nations communities were spread across their traditional lands in the wider landscape rather than concentrated in the city of Rockhampton. In contrast, the 1861 census reported that about half the European (plus Chinese, Polynesian, etc.) population in Queensland at the time lived in cities rather than in the country (https://hccda.ada.edu.au/Individual_Census_Tables/QLD/1861/census/). Broadly, then, about twice as many people living outside the city (and thus, most likely to encounter a taipan) were First Nations rather than European (i.e. around 600 versus 300 people). If ‘the Dietrich taipan’ was indeed collected by an Aboriginal person, the role of First Nations people in the ‘discovery’ of the taipan by Western science thus may be even greater than revealed by our analysis (below) of events in the 1920s.

Recognising ‘the Dietrich taipan’ as a new species

Wilhelm Peters took up a position at the Museum für Naturkunde (Berlin Museum of Natural History) in 1856, and the snake provided by Dietrich to the Godeffroy Museum eventually was moved to the larger Berlin-based institution (accession number ZMB 5883; exact date of its arrival not known). According to Curator Peter Bartsch, ‘The original catalog entry probably is in W.C.H. Peters’ own handwriting and done when he was the director of the Museum. The snake is male and 2.32 m in length’ (P. Bartsch, pers. comm., January 2007).

Peters had earlier received the taipan (and some other specimens) from Johann Schmeltz, the curator of the Godeffroy Museum (Sumner 1985). The snake had been identified as a king brown snake (Pseudechis australis), and Peters initially accepted this identification. His comments on the list of specimens sent to him by Schmeltz included ‘Godeffroy No. 2131 Pseudechis australis’ (dated 21 December 1866) (H. Landsberg, pers. comm., 1 February 2007). We do not know who made that erroneous identification, but Ray Sumner doubts that it was Dietrich herself. Sumner wrote to us that ‘the burden of identification was mainly on Schmeltz before the Museum Godeffroy sold up and he went to the Netherlands’ (Ray Sumner, pers. comm., 6 August 2024). By the following year Peters had examined the snake more closely and concluded that it was a different species to P. australis. He subsequently named it Pseudechis scutellatus (Peters 1867; see Fig. 4).

The holotype of the coastal taipan (ZMB 5883) obtained by Amalie Dietrich, from the collection of the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin. Note the everted hemipene. (photograph by Frank Tillack).

Gerard Krefft, Curator at the Australian Museum, listed the new species in the Appendix (p. 100) to his Snakes of Australia (published in 1869 (Krefft 1869)). The species is also listed along with several other species of Pseudechis by Edgar Waite in his A Popular Account of Australian Snakes (1898). He suggested its first vernacular name, ‘yellow-bellied snake’, a name that does not appear to have ever been used again. He gives its distribution as ‘Queensland and New Guinea’ and its length ‘3 feet 6 inches.’ Presumably Waite had access to Boulenger’s Catalogue of the Snakes of the British Museum vol III (published in 1896) which included an entry on Pseudechis scutellatus. That entry gave details of the type specimen obtained from Queensland as well as of two specimens held in the British Museum that had been collected in the Fly River district of New Guinea (see below). Waite’s basis for stating that the species’ length was ‘3 feet 6 inches’ is unclear, given that all three specimens known at that time were well in excess of this length.

More taipans become known to science

Less than 20 years after the first taipan had been obtained by Dietrich, two taipans were acquired by a Scottish missionary, Reverend Samuel MacFarlane, from the Fly River area in what is now Western Province of Papua New Guinea. One measured 1435 mm and the other 1685 mm (M. O’Shea, pers. comm., 20 April 2024) (see Fig. 5). They were killed, preserved in alcohol and eventually accessioned into the collection of the British Museum on 20 May 1886, under the name ‘Naja’ (the generic name now reserved for cobra species from Asia and Africa). The specimens are now held in the Natural History Museum (NHM), London (formerly known as the British Museum of Natural History). According to emails to the authors from the Herpetology Department (7 November 2023) and Professor Mark O’Shea (20 April 2024), the data accompanying the specimens read: ‘registration #s 86.5.20.14–15; collection locality Fly River, Western Prov., PNG; collected by S. MacFarlane: purchased from Gerrards’. A note in the bottle containing these snakes reads ‘86.5.20.14–15. Pseudechis scutellatus. Fly River, New Guinea. E. Gerrard’.

The two coastal taipans obtained by MacFarlane in the Fly River region of Papua New Guinea in or around 1885; both specimens are now in the collection of the Natural History Museum, London. Photographs by Mark O’Shea.

These snakes had been purchased from ‘E. Gerrard as part of the MacFarlane collection’ (email to authors from NMH Herpetology, 7 November 2023). Edward Gerrard was the founder of his family’s business that specialised in the sale of zoological specimens, skeletons and taxidermied mounts to museums. He also worked for the British Museum from 1841 for almost 50 years (Morris 2004). It is likely that Gerrard either bought the specimens from MacFarlane or was acting as his sales agent. Given that MacFarlane explored the Fly River in 1875, 1882 and 1885 (van Steenis-Kruseman and van Steenis 1950) and returned to Scotland in 1886, the taipans were probably collected in 1885, the year before he left for Scotland. So, by this time, three snakes which would eventually be identified as coastal taipans were preserved in specimen jars in museums in Berlin and London, but none in Australia.

As is the case for the ‘Dietrich taipan’, we have no direct information on who actually collected the Fly River snakes. Based on his writings, MacFarlane himself was mostly focused on converting Indigenous people to Christianity rather than on collecting zoological specimens (MacFarlane 1889). The Papua New Guinea snakes appear to have been killed by being hit on the forebody (possibly with a sharp implement like a machete) rather than shot (see Fig. 5), suggesting that the snakes may have been collected by local people (O’Shea et al. 2016). In keeping with that inference, we know that explorers in this region at around this time purchased many reptiles from native people (O’Shea et al. 2016). For example, Luigi D’Albertis (who had accompanied MacFarlane on an earlier expedition) noted in his 1877 diary: (p. 200) October 16th. ‘About 200 natives of Matzingare arrived at Moatta to-day. Some of these Bushmen brought me some fine reptiles, for which I immediately paid with tobacco’; (p. 203) October 17th. ‘Attracted by the smell of tobacco, […] the natives of Matzingare come to me every day, bringing animals, especially reptiles’; (p. 204) October 17th. ‘Meanwhile, my collection of reptiles is increasing; specimens like those I found at Naiabui and Yule Island, which I have previously described, but which were lost in the shipwreck, often come into my hands’; (p. 204) October 26th. ‘During the last few days I have continued to receive specimens from the people of Matzingare’.

Other taipans may have been collected but did not find their way into museum collections. For example, in his 1952 book Dangerous Snakes of Australia, Eric Worrell writes (p. 26) that ‘Late last century two specimens [of taipans] were recorded from Birdum, Northern Territory, but there is a possibility of error in locality’. The first taipan to be accessioned into an Australian museum collection was a specimen donated to the Queensland Museum in the early 1900s (accession no. J201). The snake was donated to the Museum by Dr Thomas Lane Bancroft but there are no extant data regarding date of collection or any field notes. Nonetheless, Dr Glenn Shea (pers. comm., June 2025) has pointed out to us that the date of collection can be inferred from knowledge of Bancroft’s work. Bancroft was a government medical officer based at Stannary Hills (the source location of most of the snakes reported by de Vis (1911)) in 1908–09. The Stannary Hills snakes presumably were obtained in this period, as was the type of wilesmithii from Walsh River (at the time, a mining area on the upper reaches of the Walsh River, close to Stannary Hills). The only Wilesmiths in Queensland at the time were a family of miners living in Watsonville (near both Stannary Hills and Walsh River). Bancroft likely would have known the Wilesmith brothers (who may well have given him the snake) and asked de Vis to name it after one or more of them.

Based on this specimen from Walsh River, north Queensland, Charles de Vis (the curator of the Queensland Museum at the time) described the new species as Pseudechis wilesmithii in a 1911 publication entitled ‘Description of snakes apparently new’. The specimen measured 2215 mm in total length. Based on the body size (male taipans grow larger than females: Shine and Covacevich 1983) and thick tailbase, we believe the animal was a male (Fig. 6). Its head is disfigured, apparently because the venom glands were removed at some point (Ingram and Covacevich 1981). Bancroft was clearly a prolific collector (see Mackerras and Marks 1973), having ‘presented’ six of the seven species that de Vis described in the paper. Unfortunately, none of those species are currently regarded as valid. de Vis should have been familiar with Boulenger’s (1896)Catalogue of the Snakes in the British Museum by this time and it is therefore surprising that he did not identify this snake as P. scutellatus. However, de Vis’ taxonomy was slapdash. The leading British scientist George Albert Boulenger wrote in 1885 ‘through his incompetence and want of care, he will do much harm … one can only wonder at his daring to write on subjects of which he is so manifestly ignorant’ (Boulenger 1885).

The specimen upon which de Vis based his description of ‘Pseudechis wilesmithii’ (now synonymised with Oxyuranus scutellatus), in the collection of the Queensland Museum. Photograph by Kevin Markwell.

A few years later, after de Vis had retired from the Queensland Museum, a scientific assistant (Heber Longman, later to become Director) of the same institution cast doubt on the validity of Pseudechis wilesmithii and renamed it as Pseudechis scutellatus. In Longman’s paper he also referred to another specimen of P. scutellatus (QM # J3729) that had been received from William Henry Edwards, a grazier at Congoola Station, Colosseum, North Coast Line, Queensland. Longman argued that P. wilesmithii was a junior synonym of P. scutellatus (Longman 1913).

The next taipan to be accessioned into an Australian natural history museum was a specimen collected from the Claudie River in Cape York Peninsula during an expedition led by James Kershaw in 1913. Kershaw was, at the time, the Curator of Zoology at the Museum of Victoria (Kershaw 1915). Interestingly, William McLennan, who collected one taipan and acquired another in 1922 (see below) was a member of that expedition. The significance of the snake specimen collected on this expedition was not realised as Kershaw simply mentions that ‘A tree snake and two or three other species were also captured’ (Kershaw 1915: p. 166).

Just a few years later, another taipan was donated to the Queensland Museum. This snake appears to have been collected on 1 August 1915, from ‘Koolpunyah’, (actually Koolpinyah) in the Northern Territory, approximately 40 km east of Darwin. It was registered in the collection on 31 July 1917 (Queensland Museum Collection database, Andrew Amey, pers. comm., 9 July 2025). Originally the snake was entered into the register as Pseudechis scutellatus (A. Amey, pers. comm., 25 June 2024) but was later reidentified as Oxyuranus scutellatus. This is a notable specimen because it was the first coastal taipan to be collected for science in the Northern Territory (discounting Worrell’s 1952 unsubstantiated report of two specimens from Birdum, Northern Territory). However, the presence of this Northern Territory snake went unnoticed for several decades. Indeed, the first published mention of this snake is in a short paper by Graeme Gow (1980), in which he acknowledges the presence of this taipan from Koolpinyah station but incorrectly gives the date of acquisition as 1925.

The ‘McLennan taipans’

By 1915, a total of six snakes which would ultimately be identified as coastal taipans had found their way into the domain of Western science: one from Rockhampton and held in Germany, two from what is now Papua New Guinea held originally at the British Museum (and now in the Natural History Museum, London), two in the Queensland Museum; and one in the National Museum of Victoria (see below). However, published historical accounts of the ‘discovery’ of the coastal taipan have claimed that following the snake obtained by Dietrich, the next taipans collected were by William McLennan in the Coen district in Cape York Peninsula (see Jones 1977; Markwell and Cushing 2016; Murray 2017).

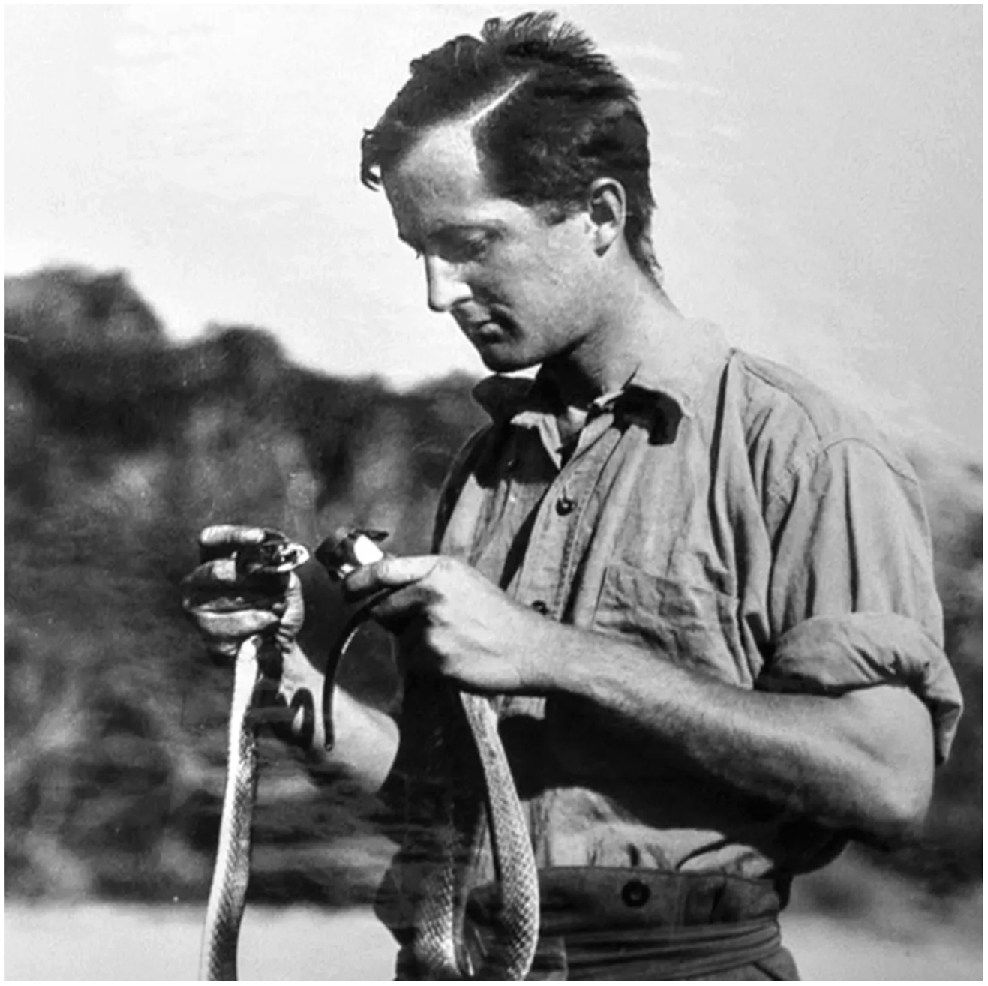

William Rae McLennan (Fig. 7) was a highly skilled ornithological collector who had travelled to Cape York Peninsula to collect birds and bird eggs on behalf of Henry L. White, a wealthy grazier and an active member of the Royal Australasian Ornithological Union (D’Ombrain 1936). White was an enthusiastic collector, with interests in stamps and rare books in addition to birds. His collection of 8500 bird skins and 4200 clutches of eggs was eventually donated to the National Museum of Victoria (Gray 1990). White employed McLennan, who had a reputation as an excellent field ornithologist and collector, to obtain specimens from Cape York Peninsula. He was particularly keen to secure specimens of the buff-breasted buttonquail (Turnix olivii) (White 1922).

William McLennan, who obtained two taipans from Cape York Peninsula in 1922. Photograph from an obituary written by D’Ombrain (1936).

H. L. White’s correspondence (Letterbooks and papers of H. L. White of Belltrees, 1886–1927, with White family papers, 1850–1986, call numbers MAV/FM4/10946) in the State Library of New South Wales includes letters to his financial advisor about McLennan’s employment. He refers to McLennan as ‘a man who collects ornithological specimens for me’, so the snakes were clearly peripheral. White also notes that ‘he is paid 20/- per day including Sundays, and his allowances food etc. accrue to over £2 per week: his total pay is therefore more than £10 per week. The life is a hard one and requires special knowledge’. For context, average annual wages in 1920 in Victoria were £205 for male factory workers, about £300 for male managers and clerks (https://guides.slv.vic.gov.au/whatitcost/earnings), much less than McLennan’s annual wage of more than £500. White also notes that ‘there is no written agreement between us’. In short, White obviously held McLennan in high regard for his collecting abilities.

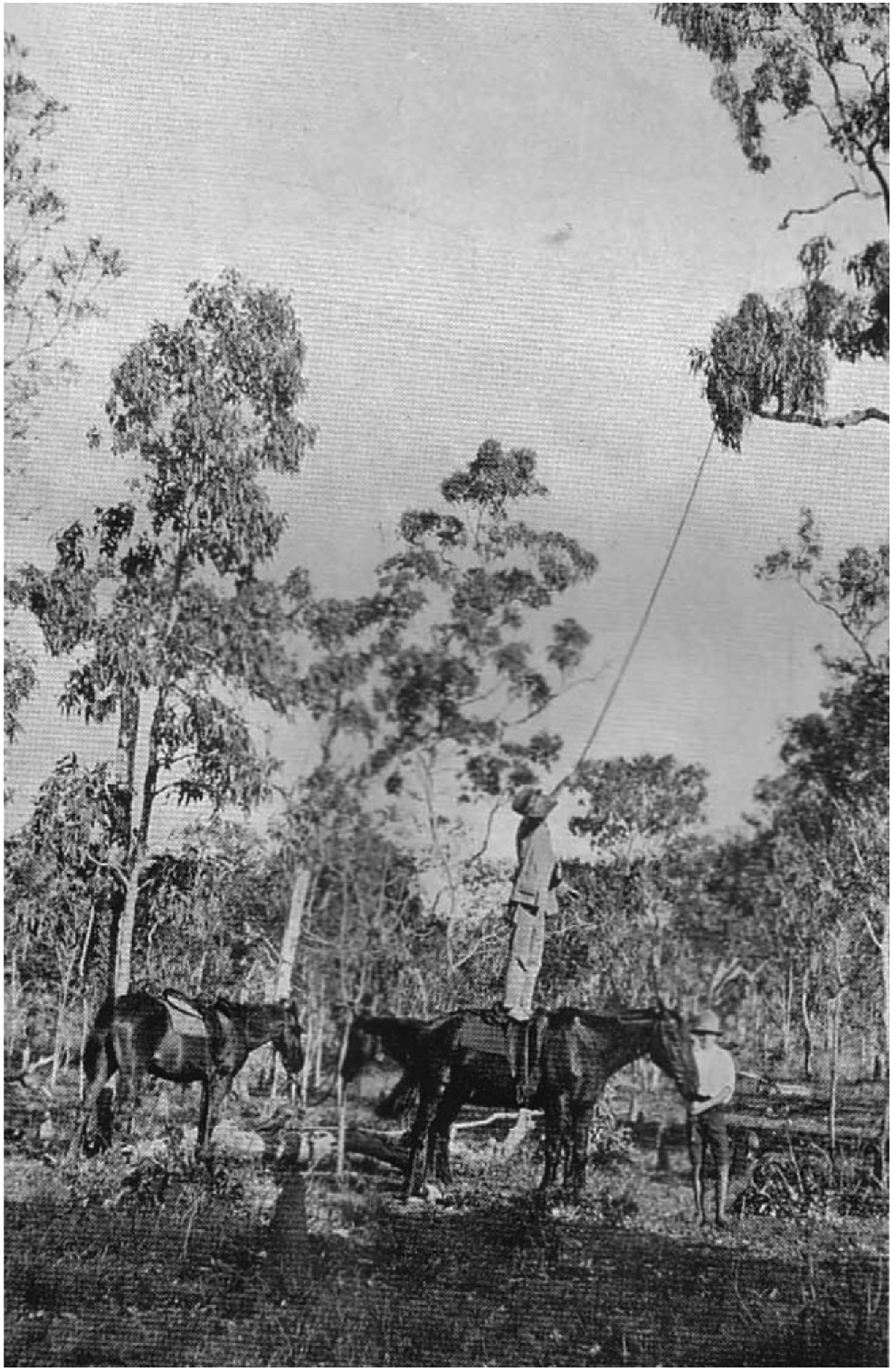

McLennan left Cooktown on the ketch, Elam, on 27 August 1921, arriving over 300 km north at Port Stewart three days later (White 1922). He reached Coen by early September and spent nine months in the vicinity, often under highly adverse conditions, collecting birds and eggs for White (Fig. 8). He was assisted in this work by several Aboriginal men (White 1922), who looked after his horses and provided expertise in tracking and collecting birds.

It is clear from McLennan’s diary that he was a hard-working, highly skilled collector who was willing to take risks. In this photograph he shows one of the methods that he employed: using a precarious perch to obtain bird eggs from a nest high in a tree.

McLennan noted encounters with several snakes during this trip, including the first recorded sighting of the green tree python (Morelia viridis) in Australia (Shea 1987). He described it as a ‘beautiful and brilliant snake with an irregular white stripe down centre of the back and tiny irregular spots of white on sides of body; it was about 5 feet long, and as thick as one’s wrist’ (W. McLennan, unpublished diary, 1922). However, it was a very large, brown-coloured snake that he encountered on 21 March 1922 which is most relevant to this paper.

At the end of his trip, McLennan produced an unpublished type-written diary to document his day-to-day activities and discoveries for his employer, H. L. White. Some of the highlights from this diary were summarised by White to write his 1922 paper in The Emu. Fortunately, McLennan’s diary describes his encounter with the taipan in considerable detail. Because one of his target species was the rare buff-breasted buttonquail (Turnix olivii), McLennan scanned the ground as well as the trees during his search for this elusive bird. Below, we reproduce his diary account:

Tuesday, 21.3.22: Turn out at daybreak and go along to where I heard the Turnix calling yesterday evening.

Head westward through likely looking Turnix country on a Iow sandy messmate, bloodwood, and ironbark covered ridge. My attention was divided between the ground and the trees, Looking out for Turnix and lorikeets. Once, on looking down while I was riding through some fairly long grass, I saw that I was right over the top of a big snake, a black-headed python I thought judging by the size of it, for I could not see it plainly, and so did not feel anxious as this snake is very sluggish and inoffensive. A second later, having passed over it, I saw its head. Hell! It’s a brown snake. Did not have my gun or pistol, so call to Tommy to cut a strong sapling, meanwhile keeping my eyes fixed on it. Tommy brought the sapling along and watched the snake while I dismounted. As I dismounted it started off, Tommy sprang on my horse to watch and I grabbed the sapling and got in a solid blow, quickly followed by a second which effectually stopped it. Approaching closer I saw that I had broken its back 2 feet from the head, gave it another smack nearer the head and quietened it then pinned the head down, got a grip and dragged it out into a clear patch.

It is a tremendous reptile, the biggest of the kind I have ever seen. While trying to sever the spinal cord by way of the mouth with my sheath knife a stream of crystal clear poison squirted out from one of its great fangs, and I dropped it like a red hot coal. Had another go at it, this time with the tomahawk, which proved more effectual and I now examine it at leisure. A swelling mid-way along the body shows that it had dined lately and probably accounts for it not trying to bite the horse or myself when I rode over it. Stretch it out and pace the length – three yards easily. Have a look at the fangs; on the right side there are 2, one behind the other, on the left side one, each a good 3/8 of an inch long; behind the fangs a couple of small teeth, between them two rows of fine needle-like small teeth; at the points of lower jaws a fair sized tooth over an eighth of an inch long, behind these smaller teeth. Colour above a beautiful dark brown with a golden sheen, below pale cream. Take the saddle cloth (a bag) off my horse, put the reptile in, roll it up and strap across pommel of saddle, and continue our way westward to a big valley at the mouth of a gorge in Geikie range.

Reach camp 2 p.m. lunch. Get to work on the snake. Total length 9 ft. 3 in.; girth 8 in.; poison fangs 15 mm. from point to tip of jaw, 18 mm. apart, they are hollow to within 3 mm. of the tips, not grooved or channeled; the sides of groove or channel have grown together thus forming the hollow through which the poison is forced; 10 mm. behind the fangs on right side one tooth 2.5 mm. long; on left side 2 teeth 2.5 mm. long; between the fangs two rows of very small teeth. The fangs are recurved, aperture of hollow on convex side or front of fangs. Bottom jaw two rows of teeth, first on each side 3 mm. long, rest very small. Squeeze the poison out of sacks or glands through the fangs and collect it in a tube, the first lot was crystal clear and slightly glutinous; on exposure to air it rapidly coagulated. When glands were nearly empty the poison got slightly milky. Not having a small tube I collected a few drops of the crystal clear poison in a quill and allowed it to coagulate. Wash the fangs and mouth out with a strong solution of Pot. permang. and proceed to take the skin off. Reach the spot where its dinner (a Dasyurus) lay and was nearly suffocated by the smell of it. Get skin off pretty lively and the carcase well away to leeward of camp. Preserve skin with arsenical soap and put it in the shade to dry. Needless to say I’ll be more careful of snakes in future. I was always under the impression that the death adder was the only Australian snake with hollow fangs and that the bite of a venomous snake would only show two punctures, thus.; from now on every snake that I see is very dangerous till it is dead and every bite poisonous whether it shows two or two dozen punctures, for I have too long been thinking if bitten through thick clothing by one of these snakes that the poison would be absorbed by the cloth. …

McLennan also provides information about his acquisition of a second taipan specimen a month later, and the possible consequences to his health, as follows:

Monday, 24.4.22: Turn out at daybreak and develop the film. After breakfast I set to work on eggs of anthill parrot. While I was at work a native (Friday Wilson) brought along a big brown snake, that he had only just killed a quarter of a mile away in bed of Coen River; it measured 8 feet 6 inches, and its top jaw was armed with four great poison fangs. Too badly knocked about to make a skin, so skin head, take out poison glands, squeeze poison into a phial, then cut off all flesh of head and put in a solution of pearl ash. Afternoon: turn in for a much needed sleep; night: print off a packet of cards of anthill parrot’s nest and eggs, finish up about midnight again.

Tuesday, 25.4.22: Feeling very much off colour. … Afternoon and night, I try to get my writing finished off, but failed.

Wednesday, 26.4.22: Still very much off colour. Try several times during the day to get on with my writing, but get very little done; am all the time dozing off, and am beginning to think that I must have got some of the snake poison into my system yesterday.

Thursday, 27.4.22: Still very much off colour; do not go out anywhere.

These detailed, first-hand notes show that the two taipans were collected at different times, in different places, by different people. Contrary to that fact, it has been assumed by some authors that the two snakes had been caught together. That error can be traced to Jones’ (1977) book, Search for the Taipan. Jones wrote (p. 64) that McLennan had ‘killed a pair [our emphasis] of very large brown snakes on the Cape York Peninsula, which he sent to the Australian Museum’ (Jones 1977: p. 64). ‘Pair’ could be understood as either two individual snakes collected on the same day or two snakes that had been found and collected together. Masci and Kendall (1995: p. 7) appear to have interpreted this in the former way and refer to ‘two large brown snakes’ that were ‘killed’ by McLennan in 1923. However, Murray interpreted the word differently (2017: p. 14). He wrote:

It was in a paddock five miles out of Coen that McLennan happened upon two enormous venomous snakes. In all probability he caught them off guard. Taipans – like most snakes – do not cohabitate, and are only found together while mating, or when males are fighting for females. Seizing this opportunity, McLennan shot them both.

Murray has imagined that the two snakes had been either two males that had been engaged in ritual combat or that they had been a male–female pair that had come together to mate. While this was no doubt a device to provide a more colourful imagined account of the ‘pair of snakes’ that Jones had claimed had been found by McLennan, common in creative non-fiction, it distorts the real situation considerably. Murray also states the snakes had been shot, when it’s likely that neither had been. McLennan’s snake was killed by striking it with a sapling while Friday Wilson’s snake had most likely been battered to death, resulting in a body that was no longer suitable for fixing in preservative.

The neglected role of First Nations assistants and collectors

To our knowledge, no published account of the first-collected taipans mentions the role of Indigenous people in the collection of these formidable reptiles. That omission is typical of early reports: specimens that were collected by Aboriginal people were credited to the Europeans who received the animals (Olsen and Russell 2019).

Indeed, ‘the Dietrich taipan’ from 1866 was as likely to have been collected by a First Nations person as by a European, given the relative numbers of the two groups in the Rockhampton area at the time.

Second, the two taipans obtained by MacFarlane from the Fly River in Papua New Guinea are likely to have been purchased from local communities, who sold many reptiles to the expedition.

Third, Aboriginal men played pivotal roles in obtaining ‘McClennan’s taipans’. Ironically, given Murray’s (2017) obvious deep respect for Aboriginal people who had been caught up in the early history of the taipan, his imagined account of McLennan finding them removes any involvement by First Nations people. In fact, ‘horseboy’ Tommy Tucker (a ‘blacktracker’ seconded from the Coen police force) assisted in the capture of McLennan’s first specimen. He cut the sapling that McLennan used to batter the snake to death and then sprang onto McLennan’s horse to keep watch on the snake’s whereabouts so that McLennan could kill the animal. The very large size of this specimen (Fig. 9, Table 2) would have made its collection a daunting task for any person on their own. McLennan had several Aboriginal assistants during his time in Cape York but in his diary he complains that some were unreliable. Tommy was clearly his favourite assistant and was expert at finding birds and their nests as well as taking care of horses and camp duties.

This photograph reveals the very large size of the taipan collected by McLennan, donated in 1922 to the Australian Museum by Henry White. Co-author R. Shine included for scale. Photograph by Kevin Markwell.

| Museum tag | Year | Location | ‘Collector’ | Museum where held | Total length (mm) | Sex | Register # | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5883 | 1866 | Rockhampton | Dietrich | Museum für Naturkunde | 2230 | M | 1888566 | |

| (86.5.20–14) | 1886 | Southern PNG | MacFarlane | BMNH | 1435 | F | 1435 | |

| (86.5.20–15) | 1886 | Southern PNG | MacFarlane | BMNH | 1685 | F | 1685 | |

| J201 | 1908–09 | Walsh River | Bancroft | Queensland Museum | 2215 | M | ||

| R12693 | 1913 | Claudie River | Kershaw | Museums Victoria | 1530 | M | ||

| J2973 | 1915 | Koolpinyah | Unknown | Queensland Museum | 1821 | M | ||

| R7901 | 1922 | Coen | McLennan | Australian Museum | 2819 McLennan; 2760 Kinghorn | M | ||

| R7900 | 1922 | Coen | Wilson | Australian Museum | 2545 (specimen lost) | M |

PNG = Papua New Guinea; BMNH = British Museum of Natural History. Note that the column ‘Collector’ refers to the person who obtained the snake, and in some cases was not the actual collector.

The Queensland State Archives indicate that Tommy was moved from Coen to Palm Island in 1928 with his wife Maudie (https://www.cifhs.com/qldrecords/qldcookoccur.htmland). This was a penal colony with horrendous conditions and high mortality rates, and we do not know why Tommy was sent there; the criteria for moving people to Palm Island were very broad, and included refusal to comply with regulations under the Aboriginal Act. Letters in the Archives note that Tommy absconded rather than being forcibly removed to Palm Island, and that his formidable bushcraft skills made it difficult for police officers and trackers to capture him. He returned to Coen prior to his death at Ell Creek, Coen on 22 October 1931 (predeceased by Maudie, who died on 17 January 1931: https://www.cifhs.com/qldrecords/A58973_Qld_Deaths_1910_1928.html). The only other information we have about Tommy Tucker comes from Tim Jaffer (pers. comm., 29 April 2025), who notes that Tommy had a son named Johnny Crooked Foot (also a Kaantju man). We have not been able to find any photographs of Tommy Tucker. The name ‘Tommy’ was commonly given to Aboriginal men; and ‘Tommy Tucker’ was a central character in an English nursery rhyme that was popular at the time. The consequent popularity of the name makes it difficult to identify specific individuals.

The contribution of Friday Wilson was even greater; he collected McLennan’s second specimen, presumably single-handedly. Wilson was born around 1880, so was about 41 years of age at the time. The snake was killed ‘in the bed of the Coen River’ according to McLennan’s diary. Personal communication from Mr Allan Creek of Coen in 2023 (via D. Natusch, pers. comm., August 2024) reveals that ‘Friday Wilson was from between Beetle and Wilson Creek, on the way to Peach. He belonged to a Dingo Story. Southern Kaantju man. He was a lighter skinned old fella who lived on the Lankelly Creek in a shack just up from the bridge.’ Lankelly Creek runs into the Coen River, and we surmise that the snake may have been encountered and killed close to Friday Wilson’s home. Defence of his home against a dangerous intruder might have provided Friday with motivation to attack such a formidable animal, and to do so with enough violence to ensure that it was incapable of biting.

Most of the information that is available about Friday Wilson reflects his involvement in mining. Galiina Ellwood’s chapters and articles Ellwood (2014, 2017, 2018) on the involvement of Aboriginal people in gold mining on Cape York Peninsula provide a chilling account of Wilson’s early life (Ellwood 2018: p. 86): ‘As a baby of around 10 months, Frederick ‘Friday’ Wilson was found in 1881 by Charlie Wilson, one of the early diggers on the Coen goldfield, on the track from Laura to Coen. There is no record of why he was there, but was probably the survivor of a massacre of Aborigines’. In contrast, an obituary of Wilson (Anonymous 1950) talks of him being ‘rescued from his tribe’ and ‘reared by some very kind-hearted whites of the early pioneer days named Wilson’. We could find no specific evidence to clarify Wilson’s origins, but it is clear that massacres of First Nations people were common in that area at around that time (e.g. Cole 2004; Wallis et al. 2022; https://database.frontierconflict.org/entries/entry?EID=47309).

Despite his tragic beginnings, Wilson later became a successful businessman:

Charlie Wilson adopted the boy and he grew up as the foster brother of Johnny Wilson. … Friday and Johnny went into business as teamsters, using horse teams and drays. They also … were recorded as mining at Coen in 1896 and Ebagoolah in 1901. Johnny was accidentally killed in 1906 and Friday went mining full-time … He sometimes worked with white people, and in 1936 he took up a claim with Herbert James Thompson and John Louis Basani, while in the early 1930s he was working for Duke Delaney at the New Years Gift mine on the Batavia, at Lower Camp. … in a 1936 newspaper report the Mining Warden records him as having a miner’s right and a lode mining claim there. The newspaper also said that ‘he works on his own in a most methodological fashion’ and that he was constructing a blacksmith’s shop at the mine, presumably to sharpen rock drills and make repairs …. Friday died in 1950 [at the age of about 69] at the Coen Hotel, where he was living’ (Ellwood 2018: p. 87).

Interestingly, ‘Friday Wilson was the only Queensland Aborigine of that period to have an officially registered gold mining lease in his own name’ (Ellwood 2017: p. 44). Unusually for an Aboriginal person of the time, Wilson was literate, had been adopted by a white family, integrated well with the white community, and apparently was generally respected and accepted (see Fig. 10). Those factors doubtless helped when he applied for exemption from section 33 of ‘The Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act’. Under that Act, it was ‘lawful for the Minister to issue to any halfcaste, who, in his opinion, ought not to be subject to the provisions of this Act, a certificate, in writing under his hand, that such halfcaste is exempt from the provisions of this Act and the Regulations’. Wilson’s name appears in the register of applications for 1946, when he was 65 years old. His exemption ‘allowed [him] to live outside the Aboriginal Act’.

The man on the left is thought to be Friday Wilson, in this photograph from the Blue Mountains gold-mining battery near Coen (c. 1930s), reproduced from Ellwood (2018).

We note that the first taipan to be collected alive, by Donald Thomson (see below), also was obtained with assistance from Aboriginal people. In a typewritten manuscript about the snake’s capture (Queensland Museum archives), Thomson notes that he found the snake when it bit and killed ‘a native dog’. Given that Thomson routinely lived with First Nations communities, it seems probable that he was alerted to the snake’s presence by the owners of the dog. Additionally, the type specimens of the inland taipan (Oxyuranus microlepidotus) were also likely provided by First Nations people collecting specimens for Krefft, who was working for William Blandowski, on the Murray–Darling in the early 1850s (see Allen 2009).

Scientists examine the ‘McLennan taipans’

Both of the snakes obtained by McLennan were stored in the field until he left Coen in June 1922. At some point after returning from the field, McLennan passed on all his specimens, including the material from the two large brown snakes to his benefactor, Henry White. Table 2 lists the taipan specimens described as new species or genera by early scientists.

White’s financial ‘letterbook’ correspondence in the New South Wales State Library provides an interesting perspective on McLennan’s reaction to the capture of this formidable snake, and his illness after exposure to the venom of the second specimen. We have found no correspondence from McLennan to White, but he must have written to White shortly after the snake’s capture because on 30 August 1922 (5 months later), White wrote to his financial advisor A. C. Ebsworth to say that:

This man who collects ornithological specimens for me in the North Queensland scrub, has raised the question of insurance under the Workers Compensation Act of that state. In case you do not have it in hand, I send you under separate cover a copy of the Act. Please advise whether McLennan meets with the provisions of the Act, and if so, what I should do in the matter. To my idea, I am not liable.

In a follow-up letter to Ebsworth on 4 September 1922, White accepts Ebsworth’s advice that ‘it appears that I am at risk by not insuring the man, so to be on the safe side you may fix it up for me.’ Although the motive for McLennan’s request for Workers Compensation coverage will never be known, his encounters with taipans (the first leading to significant shock, the second to possible indirect envenomation) may have alerted him to previously unsuspected risks.

McLennan’s detailed notes in his diary enabled his employer, H. L. White, to write an article about the collecting trip in an ornithological periodical (The Emu, the journal of the Royal Australasian Ornithological Union) in 1922 – the same year in which McLennan obtained the two taipans. The events surrounding his capture of the first snake are summarised in White’s paper, so he obviously regarded it as noteworthy despite his focus on birds rather than reptiles. In a letter to Charles Anderson, who was the Curator of the Australian Museum from 1921 until 1940, White (25 June 1922) wrote:

We expect the snake to be of much interest, as we can find no record of such a reptile: the skin, jaw and tubes of venom are for you and I ask that they be examined by the best available expert. No objections to you publishing the matter if of sufficient interest. If anything is written up on any of the above, please do give McLennan every credit attached to a new find.

After Anderson (or more likely, J. R. Kinghorn, see below) had examined the contents of the case of specimens that White had sent to him, he responded in a letter dated 29 June 1922:

The snake’s skins, skull, and venom are exceedingly interesting. A very large venomous brown snake, sometimes called ‘the venomous python’ occurring in Northern Queensland, has often been reported, but this is the first specimen we have seen. It may be new, but more comparative work is necessary before a definite statement can be made to its identity. It will be a pleasure to associate Mr McLennan’s name with any published work on the specimens brought by him and we shall not fail to acknowledge our indebtedness to yourself.

Anderson showed the specimens to J. R. (Roy) Kinghorn, at the time zoologist in charge of reptiles, amphibians and birds. He would later become curator of these three animal classes at the Australian Museum. Kinghorn wrote a note for Anderson (dated 4 July 1922) which Anderson used as the basis for another letter to White, dated the same day as above:

The snake is one of the most interesting I have ever examined, the external characters would place it as a Pseudechis, it being very near to P. scutellatus, the type of which is about 5 feet long and unfortunately in the Gottingen Museum [sic]. The internal, or skull characters differ from most Australian snakes and when time allows a thorough examination, the snake might prove to be a new genus.

The type specimen to which Kinghorn is referring is of course the snake sent to the Godeffroy Museum in Hamburg by Amalie Dietrich, which was still considered at that time to be a species of Pseudechis.

Importantly, his note to Anderson shows that Kinghorn recognised the affinity between the specimens provided by McLennan and the snake described by Peters as Pseudechis scutellatus. However, he later determined that the McLennan snakes were sufficiently different from Peters’ description of P. scutellatus (based mostly on scalation, cranial and dental characters) and erected a new genus, Oxyuranus, to accommodate it. He recognised McLennan’s role in collecting the snakes by giving the new species the specific epithet of maclennani, expanding McLennan’s name when he Latinised it. Although there is no requirement in the Code of Zoological Nomenclature to do so, this was common practice (G. Shea, pers. comm., 2 January 2025). Kinghorn described the new species in a paper published in the Records of the Australian Museum in 1923. Given his interest in birds (indeed, he is on record as saying he ‘disliked snakes’: Docker 2007), it is noteworthy that Kinghorn also published a short note in The Emu, later that same year (Kinghorn 1923b), titled ‘New snake discovered on a bird expedition’. He wrote:

A complete skin, containing a skull, and a second beautifully cleaned and preserved skull (both from specimens about 9 feet in length) were presented to the Australian Museum … I found that there was only one small tooth following the fang (excepting those in reserve), and this, together with several cranial characters, gave me sufficient evidence on which to decide that the snake did not belong to any known Australian genus, and wide comparisons with foreign snakes led me to conclude that it was a new genus and species, and undoubtedly the most dangerous snake in Australia.

It should be noted that Kinghorn did not examine Peters’ snake which was in the collection of the Berlin Museum of Natural History by this time (and not in the ‘Gottingen Museum’ as he stated in the note to Anderson). Kinghorn’s speculation that the snake was ‘undoubtedly the most dangerous snake in Australia’, without any information on the toxicity of the venom nor the temperament of the snake, likely was based on the length of the snake and the size of the fangs.

Kinghorn included entries for both Pseudechis scutellatus and Oxyuranus maclennani in his book Snakes of Australia, the first edition of which was published in 1929. He gives the vernacular name of ‘Giant Brown Snake’ to the latter species. He notes that ‘in general appearance and external characters this snake [Pseudechis scutellatus] is similar to and very closely allied to the Giant Brown Snake’ (Kinghorn 1929: p. 169). However, he restricts O. maclennani to ‘Cape York Peninsula extending westward to the Gulf country’ (p. 170) while P. scutellatus occurs in ‘central Queensland’ (p. 169). Scalation for the two species is given as different, with 23 rows of dorsal scales given for P. scutellatus and 21 for O. maclennani, as well as differences in ventral and subcaudal scale counts. Kinghorn also states that the anal scale is divided in P. scutellatus but single in O. maclennani. Kinghorn erred in this respect because Peters’ description of Pseudechis scutellatus gives the anal scale as ‘1 ungetheiltes Anale’ or ‘undivided anal scale’. In other words, the anal scale is single in both Pseudechis scutellatus and Oxyuranus maclennani and it could not therefore be used to separate the two ‘species’. Kinghorn may have assumed the anal scale was actually divided in the type of P. scutellatus given that he was familiar with other Pseudechis species (such as P. australis, P. guttatus and P. porphyriacus) all of which have divided anal scales (Glenn Shea, pers. comm., June 2025).

Kinghorn commented on the size, venom, diet and distribution of O. maclennani, although on what basis is unclear given that only two specimens (one a skin incorporating the skull, and the other a skull) are known to him. He includes an illustration of the head and neck of O. maclennani from above and another from the side. The skin with the head and skull intact is held at the Australian Museum, Sydney (see Fig. 9), but the second specimen (skull only; the animal collected by Friday Wilson) is apparently lost, its labelled jar sitting empty on a shelf in the herpetological collection. This is a terrible loss, given the important role it played in resolving the taxonomic identity of the snake, as we shall see in the following section.

Confusion: taxonomic and nomenclatural

The confusion over the identity of the coastal taipan was further muddied when Charles Kellaway (eminent venom researcher and Director of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research in Melbourne) and his colleague Eleanor Williams published a comparison of the venoms of what they considered to be Pseudechis scutellatus and Oxyuranus maclennani in the Australian Journal of Experimental Biology and Medical Science (Kellaway and Williams 1929). Roy Kinghorn had given them samples of venom from the two snakes that had been collected/acquired in 1922 by McLennan sometime in late 1928 or early 1929, as well as another sample of venom that had been extracted by McLennan from a snake he believed to be O. maclennani (Kellaway and Williams 1929; Thomson 1949). Kellaway and Williams note, however, that Kinghorn warned them that the sample from McLennan may have been from Pseudechis scutellatus, which he explained could not be differentiated from O. maclennani from external characters alone. The venom had been donated to them by Donald Thomson (see below) who had met McLennan on his first expedition to Cape York Peninsula in 1928 (Thomson 1949). McLennan gave Thomson several dead snakes and a sample of venom, the latter subsequently given to Kellaway and Williams.

Their analysis found substantial differences between the venoms. However, these differences can be explained if they had been testing the venom of coastal taipans against that of another taxon, given that P. scutellatus and O. maclennani were later found to be the same species. Because Thomson later identified the dead snakes he was given by McLennan as king brown snakes (Pseudechis australis), it seems most likely that the third venom sample was from this species. Although that error is surprising, Thomson had written in an article, published in 1949 in the popular magazine, Walkabout:

Few people, even among those who live in its habitat, are able to identify this snake, and most specimens which have been sent to me for determination from the Cairns district, and even specimens received from McLennan himself, collected at Coen on Cape York Peninsula where he secured the giant specimen now in the Sydney Museum, have proved to be the huge but much less deadly king brown snake – Pseudechis australis.

Thomson repeated these comments in a letter to Hugo Flecker dated 7 December 1948 (in the Donald Thomson Collection of Museum Victoria) and gives another example of misidentification in a letter to Roy Mackay of 23 February 1950 (also in the Museum Victoria collection):

You may have noticed for example, a press report of the sending of a specimen of the taipan from Coen. On arrival, however, this proved to be a small specimen of Natrix marii [sic] which as you know, is a harmless freshwater snake. In my experience in the field, amounting to the best part of 7 years on Cape York Peninsula and Arnhem Land, I think I collected only six living specimens of the taipan. Oddly enough two snakes which were sent to me by W. McLennan himself, whom I knew well and who was probably one of the best field workers Australia has seen, with a statement that they were specimens of taipan, both proved to be Pseudechis australis.

It was not until 1933, six decades after the capture of the first taipan in Rockhampton, that the taxonomic identity of this large, distinctive and medically significant snake was finally resolved. Donald Thomson spent about eight months undertaking anthropological and zoological fieldwork in Cape York Peninsula in 1928 and returned several times until 1933 (Fig. 11). He collected approximately 2000 zoological specimens and 7500 ethnographic objects and artefacts (Allen 2012). In 1929 he became a member of staff at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute (WEHI) of Medicine, where he worked on antivenoms. After leaving WEHI, Thomson made a third expedition to Cape York Peninsula in 1932, before joining the University of Melbourne where he remained until 1968, the last four years as professor of anthropology (Morphy 2002).

Donald Thomson, in the field, milking a coastal taipan of its venom in 1928. Photograph courtesy of the University of Melbourne.

Thomson published a paper in the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London in which he demonstrated that Pseudechis scutellatus and Oxyuranus maclennani were in fact the same species. However, an error still crept in at the beginning of the paper when he states that Peters described a new snake ‘under the name of Pseudechis scutellatus’ from ‘South-eastern New Guinea’ (Thomson 1933: p. 855). As we have shown earlier, two taipans had been collected from the Fly River in 1886 and deposited in the British Museum. Thomson’s error might be traced to the entry for Pseudechis scutellatus in Boulenger’s (1896)Catalogue of the Snakes in the British Museum. At the end of the entry (p. 332), Boulenger gives the following locations for the species: ‘South-eastern New Guinea, Queensland, Northern Australia’ and then provides scale counts for the two (female) specimens collected in the Fly River (Boulenger 1896: p. 332). Thomson may have transcribed ‘South-eastern New Guinea’ into his notes incorrectly as the type locality for the species.

Thomson’s analysis necessarily was based on specimens in Australia and did not include the type specimen of Pseudechis scutellatus (i.e. ‘the Dietrich taipan’). In a letter dated 7 December 1948 to Heber Longman (Donald Thomson Collection, Museum of Victoria), Thomson wrote that: ‘Just before the war I had arranged to examine Peters’ type which is or was in the Berlin Museum, to see whether it possessed the toothless extension of the palatine bone which characterises the genus Oxyuranus, but I went to America in 1939 and did not return to Europe on account of the war.’ According to this letter, Thomson’s desire to view the holotype in Berlin appeared to come later in that decade; he does not seem to have considered viewing the holotype prior to his published description of Oxyuranus scutellatus in 1933. Thomson thus based his paper on four taipans from Queensland: three from Cape York and one from ‘southern Queensland’. Of the four snakes he examined, two (the one identified as WEHI #3, and the #6 Field register) are presumably both Thomson specimens – two of the six he collected in Cape York, with #6 collected on his third and final trip to Cape York in 1932. Both #3 and #6 were from Bare Hill, a Thomson collecting locality. The third specimen is QM J3729 (the specimen from Colosseum collected by Edwards). Thomson doesn’t appear to have examined the type of wilesmithii in the same collection (Glenn Shea, pers. comm., June 2025).

But Thomson also examined another (generally overlooked) specimen: R12693 in the Museum of Victoria. Indeed, the authors of this current paper had overlooked this specimen until we were alerted to its existence by Glenn Shea (pers. comm., June 2025). This snake was the specimen collected in 1913 by James Kershaw, from the Claudie River (and is not one of Thomson’s six specimens), as mentioned earlier in the current paper. Whittell (1954) notes that Kershaw worked with McLennan, along with William McGillivray and his son Ian in the Claudie River area between November 1913 and January 1914. In other words, McLennan had actually been working with someone who collected a taipan in Cape York in 1913, a decade before McLennan collected the types of maclennani in 1922. While work was being done synonymising wilesmithii with scutellatus by Longman in 1913, a taipan was just about to be sent to the Museum of Victoria – the fourth specimen in a museum collection.