The role of conservation translocations in the recovery of the endangered Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird (Atrichornis clamosus): from Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve and back

Sarah Comer A * , Alan Danks

A * , Alan Danks  A B , Abby Berryman A , Saul Cowen

A B , Abby Berryman A , Saul Cowen  C , Allan H. Burbidge

C , Allan H. Burbidge  C and Graeme T. Smith D †

C and Graeme T. Smith D †

A

B

C

D

† Graeme T. Smith, deceased June 1999. G. T. Smith joined the CSIRO in 1970 to continue research into the ecology of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird, and was an active member of the recovery team. Graeme made a significant contribution to literature on scrub-birds, and was a coauthor on an unpublished manuscript examining the removal of scrub-birds from Two Peoples Bay between 1983 and 1987.

Handling Editor: Mike Calver

Abstract

Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird (Atrichornis clamosus) translocations between 1983 and 2018 have been a major management strategy for this cryptic semi-flightless songbird, which was once considered extinct.

We review 40 years of translocations, assessing the importance of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, Western Australia as a source of founders, and the role of translocations in Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird recovery.

An evaluation of translocation successes and failures and the impact of removing birds from the Two Peoples Bay population when it was the only possible source. Research into territorial song to explain the social structure of scrub-birds, population genetics, habitat suitability, and the implications of learnings for future translocations.

Translocation has been the major contributor to an increase in the population index and Area of Occupancy, although removal of birds from Two Peoples Bay may have contributed to scrub-bird declines in this area. A more conservative approach to translocations was developed using small initial numbers of founders. Impacts of the translocation program on the genetic diversity of the metapopulation appear not to be significant.

Conservation translocations have been instrumental in securing and conserving the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird, with considerable spatial expansion of the species range, in spite of significant bushfires impacting habitat.

With the likelihood of unplanned fire increasing, and climate change likely to modify habitat, maximising the number of geographically distinct populations remains a priority for the conservation of the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird.

Keywords: conservation translocation, Djimaalap, endangered, genetic bottlenecks, noisy scrub-bird, reintroductions, song groups, Two Peoples Bay.

Introduction

Two Peoples Bay in Western Australia was declared a nature reserve in 1967 following the rediscovery of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird (Atrichornis clamosus), and a subsequent international campaign to protect the area for the purpose of conservation of the scrub-bird (Danks et al. 2024). The Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird is a passerine (songbird), which was once widespread across the south-west of Western Australia. Currently, the only population is restricted to a small area on the south coast of Western Australia (Smith 1977; Comer et al. 2018). Historically, the scrub-bird’s origins are considered to have been in the Gondwanan temperate rainforests, which covered much of the southern part of the Australian continent and have contracted and fragmented since the Miocene (Fig. 1; Bock and Clench 1985; Mitchell et al. 2021). Scrub-birds (A. clamosus and the eastern Australian Atrichornis rufescens) are considered an evolutionary distinct species: part of the early radiation of Australian songbirds, and along with the lyrebirds (Menura spp.) are one of the earliest diverged lineages of the oscines (Chesser and ten Have 2007; Christidis and Norman 2010; Comer et al. 2018; Mitchell et al. 2021). There is significant Indigenous cultural knowledge of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird prior to European settlement and ‘discovery’, and Knapp et al. (2024) capture the cultural significance of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird through oral histories and stories told in Wiernyert/Dreaming events. Evidence of the scrub-bird’s presence in the south-west of Western Australia in the Holocene was confirmed by fossil material from Skull Cave, near Augusta in Western Australia (Baird 1991). In 1842, John Gilbert collected the type specimen of the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird near Drakesbrook in the Darling Range south of Perth and in the following year, specimens were collected in the Albany area (Fig. 2; Smith 1977).

Timeline of events in the history of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird from known origins to the commencement of the translocation program. Places named are also shown in Fig. 2.

Nineteenth century records of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird and conservation translocation sites and outcomes.

Between 1842 and 1889, scrub-birds were also recorded at Boodjidup Creek (Margaret River), Augusta, Torbay, and in the Albany region as far north as Mt Barker and east to the Waychinicup River (Fig. 2; Whittell 1943; Smith 1977). These records summarise the known 19th century distribution of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird. The apparently rapid decline post-colonisation was undoubtedly a combination of the effects of clearing, grazing, and changes to fire regimes (Smith 1977). However, it is highly likely that scrub-birds would have occurred more broadly across the south-west when the early tertiary rainforests covered much of southern Australia (Greenwood and Christophel 2005) (Fig. 1).

The Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird is a small almost flightless, sexually dimorphic passerine (Fig. 3). Females are smaller than males with a mean weight of 34.4 g (n = 72, range 30–43 g). The mean weight for males is 51.1 g (n = 179, range 44–60 g). Scrub-birds occupy dense, low forest, and scrub vegetation that provides cover, nesting habitat, and well-developed leaf litter invertebrate food resources, generally in long unburnt vegetation (Smith and Robinson 1976; Smith 1985a, 1985b). The scrub-bird breeds in winter. Each breeding female builds a domed nest, incubates the single egg, and feeds the nestling alone. Observations suggest that females have distinct nesting territories, which are on the outskirts of, or in between male territories. The female produces only a single offspring in a year (Smith and Robinson 1976; Danks et al. 1996). Its need for dense cover and limited flight capability makes the scrub-bird a poor disperser, especially in fragmented landscapes (Danks 1991). The scrub-bird’s cryptic plumage, and preference for inhabiting dense vegetation mean it is rarely seen. However, the loud territorial song of the males is a distinctive feature of any landscape inhabited by Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds. The males actively defend their territories with a far-reaching territorial song, but other vocalisations also include a short song, a three-note call, and single note calls (Smith and Robinson 1976). The lifespan is unknown, with the oldest bird, a male, known to be at least 10 years old and still actively defending a territory. A female, taken as a nestling from Two Peoples Bay in 1975 for the captive program, was 10 years old and still building nests and laying eggs before being released on Manypeaks in 1985. With low fecundity the lifespan is likely much longer than what has been observed.

Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird (Atrichornis clamosus): male (left) and female (right) (photographs Alan Danks).

In 1961, 72 years after the last confirmed record in the 19th century, Albany naturalist Harley Webster announced that Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds existed east of Albany (Webster 1962a, 1962b) (Fig. 4). This followed reports by another local naturalist, Charles Allen, of a bird that was most likely the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird, in 1944 and 1961. The story behind the rediscovery is provided in Burbidge and Russell (2018) and Chatfield and Saunders (2024). In the 1960s, fewer than 100 individual scrub-birds remained, and they were confined to a single location around the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner area at Two Peoples Bay (Smith and Forrester 1981) (Noongar names for the scrub-bird and places around Two Peoples Bay are from Knapp et al. (2024) and are given before European names). However, the scrub-bird’s limited habitat was under threat from frequent bushfire, unrestricted human access and, alarmingly, the imminent development of a townsite at the foot of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner (Chatfield and Saunders 2024). The cancellation of the proposed Casuarina townsite, gazettal, and management of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, and research by CSIRO for the protection of the small Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird population were key actions in ensuring its survival (Danks et al. 2024).

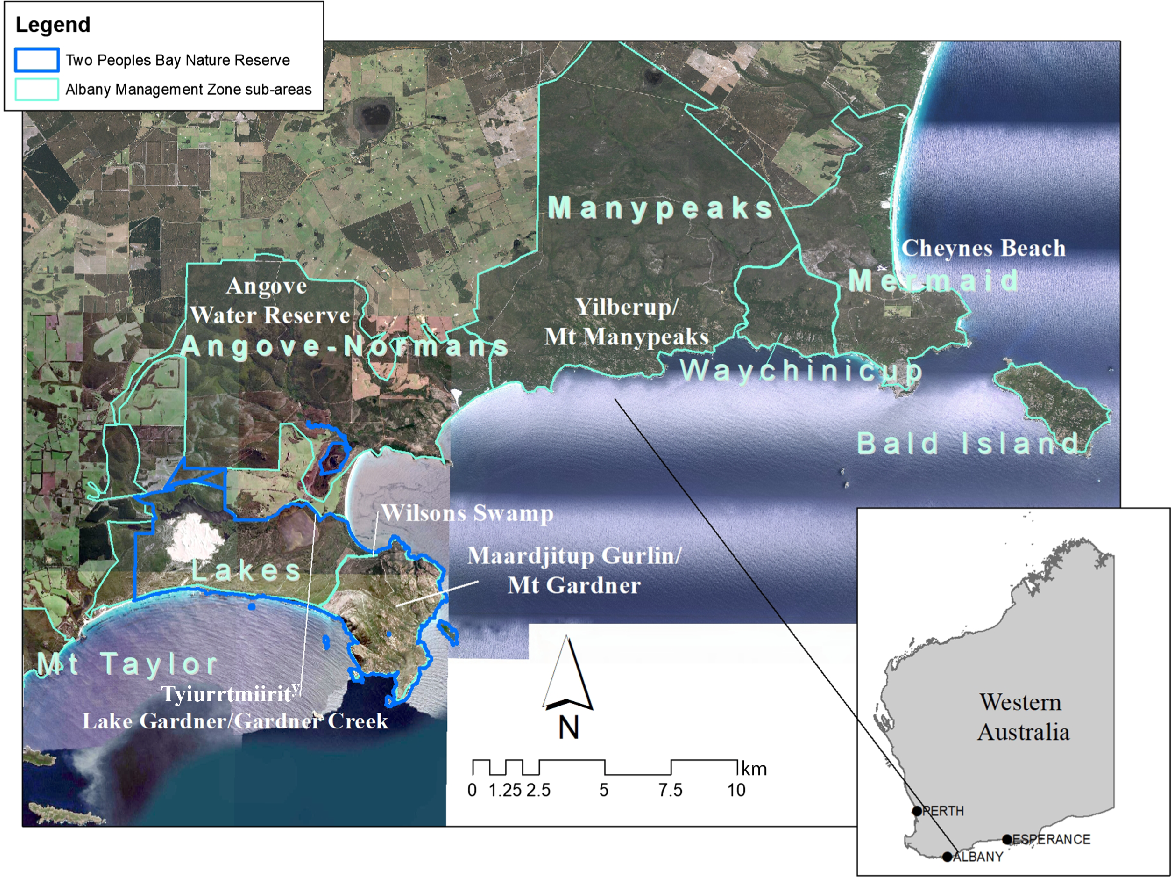

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve and sub-areas of the Albany Management Zone showing the boundaries of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird census areas (pale blue boundaries and text) and Wilson’s Swamp, giving Merningar place names and spellings (from Knapp et al. (2024)). Inset shows the location of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve on the south coast of Western Australia.

The Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird has been relatively well researched since its rediscovery, including aspects of its systematics and morphology, life history, food preferences, translocation habitat suitability, genetics, and song-sharing and repertoire, which are summarised by Bock and Clench (1985), Smith and Robinson (1976), Smith and Forrester (1981), Danks et al. (1996), Smith (1996), Gilfillan et al. (2006), Cowen et al. (2021), and Berryman (2003, 2007). Monitoring of the population is carried out through an annual census of singing males. The number of territorial males is used as an index of population size and changes in annual counts over time indicate population trends (Smith and Forrester 1981; Danks et al. 1996). The scrub-bird’s elusive nature and dense habitat it occupies make it difficult to study through direct field observation, and consequently there is still limited knowledge on some aspects of the bird’s biology and ecology, such as mating strategy and lifespan.

Conservation translocations

Conservation translocations have become a common strategy to maintain and restore populations of threatened species around the world, with the use of translocation as a management tool increasing over the past 40 years (Danks 1994; IUCN/SSC 2013; Morris et al. 2015; Gaywood et al. 2023). Translocations are the intentional movement of a species from one place to another, often in response to loss of habitat, climate change, invasive species, and other anthropogenic threats impacting populations of native fauna and flora. Conservation translocations are defined by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as either population restoration, which includes reinforcement and reintroduction within a species’ Indigenous range, or conservation introductions, comprising assisted colonisation and ecological replacement, outside their range (IUCN/SSC 2013). The IUCN’s Species Survival Commission (SSC) formalised the IUCN/SSC Guidelines for Reintroductions and Other Conservation Translocations (IUCN/SSC 2013). Formed in 1988, the IUCN Reintroduction Specialist Group (now Conservation Translocation Specialist Group) has developed the framework for planning, implementing, and monitoring the results of translocations (IUCN/SSC 2013).

A species with a small population and a restricted range is at risk from a variety of stochastic events and loss of genetic diversity, even if its habitat is well managed (Frankham et al. 2017). Active habitat management (e.g. predator management and fire management) can result in an increasing population size, and this is theoretically only limited by the availability and accessibility of suitable habitat and favourable conditions for breeding. Another method of enhancing survival chances for a species is the establishment of other geographically distinct subpopulations by translocating individuals from the extant population to other areas. In Western Australia translocations of native species have been used as a conservation tool since 1971; at least 43 fauna species, the majority mammals, have been translocated since then (Morris et al. 2015). Conservation translocations have been used less frequently for birds, reptiles, frogs, and invertebrates (Morris et al. 2015).

History of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird translocations

Conservation translocations were considered early in the management of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird. The then Department of Fisheries and Wildlife (subsequently Department of Conservation and Land Management) considered this option as early as 1965 (Young 1983). Webster also mentioned the possibility of transferring some scrub-birds to other areas, including Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks 12 km to the north-east of Two Peoples Bay, in a letter to Dr Dominic Serventy (CSIRO Division of Wildlife Research, 1 April 1966). In the early 1960s there was a clear acknowledgement of the risk to the Two Peoples Bay population from potential stochastic events such as bushfire (Webster 1962a, 1962b). Concerns about genetic diversity were also raised, and these were particularly relevant given the small population size when the scrub-bird was rediscovered (Burbidge et al. 1986). In addition, there was recognition that the area of suitable scrub-bird habitat in Two Peoples Bay was limited (Danks 1994).

The small numbers of scrub-birds, lack of population growth on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner, and the need for secure tenure in the proposed translocation site at Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks required significant planning and management of the source population (Young 1983; Danks 1994; Danks et al. 2024). The possibility of using captive-bred birds to establish new subpopulations led to the establishment of an ex-situ captive breeding program by CSIRO between 1975 and 1981 in Perth, Western Australia. However, the program only raised one chick to adulthood and was judged unlikely to support a translocation program (Davies et al. 1982; Smith et al. 1983; Garnett and Crowley 2008). The growth of the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner population (Smith 1985a), combined with the gazettal of Mt Manypeaks Nature Reserve (Young 1983), prompted the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife to initiate a translocation program in 1983. The translocation of the scrub-bird to Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks in 1983 was the first avian conservation translocation in Western Australia (Burbidge et al. 1986; Danks 1994; Danks et al. 1996; Morris et al. 2015).

Conservation management of scrub-birds was originally led by the Western Australian Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, part of which is now the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA). Research was undertaken by CSIRO’s Division of Wildlife Research under an agreement with the Department of Fisheries and Wildlife. The first management plan for the species was written in 1986 (Burbidge et al. 1986) and a recovery plan followed in 1996 (Danks et al. 1996). A single species recovery team was formed in 1992 and since 1996, scrub-bird recovery has been guided by the South Coast Threatened Birds Recovery Team, with habitat management, monitoring and research coordinated by the DBCA’s South Coast Region (Burbidge et al. 2018).

In 1983, a trial Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird translocation project was conducted to establish basic techniques for capturing, holding, releasing, and monitoring scrub-birds (Burbidge et al. 1986). Following the apparent success of the first translocation, translocation was incorporated into the management plan as a major recovery strategy (Burbidge et al. 1986). The main objective of the management plan was the establishment of additional subpopulations to ensure at least four separate reproducing subpopulations exist at any one time. This strategy has continued under subsequent recovery plans for the species (Danks et al. 1996; Comer et al. 2010; Department of Parks and Wildlife 2014).

In the early years of the conservation translocation program, Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve was the only possible source of scrub-birds. It was not known how many scrub-birds could be removed without affecting the population. However, there was a clear understanding that the effects of regular removal of breeding adults needed to be monitored, to ensure that this could be sustained without negatively impacting the source population (Danks et al. 1996).

The IUCN/SSC Guidelines for Reintroductions and Other Conservation Translocations (IUCN/SSC 2013) emphasise the importance of considering social relationships of founder groups. Berryman (2007) found that territorial male scrub-birds form song sharing groups of up to 10 birds, with neighbouring song groups having no song types in common. In addition, males change their songs over time, with all members of a song group making the same changes to their shared song types (Berryman 2007). The combination of extensive song sharing and rapid repertoire change meant that recognising individuals from their songs was impractical (Berryman 2003; Portelli 2004), and males likely learnt their songs from their neighbours on an ongoing basis. Berryman (2007) proposed that song groups were akin to an exploded lek where a dominant male drives changes to shared songs, and song sharing may be a factor in creating a cohesive group of founders, hence influencing successful establishment of translocated birds. If song groupings are important in the social structure of the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird, sourcing birds for translocation from the same song groups may play a role in maintaining social cohesion and may be important for successful establishment at the release site.

The IUCN/SSC Guidelines also highlight the critical importance of genetic management when establishing new subpopulations (including ensuring founder groups provide adequate genetic diversity), and subsequent genetic monitoring (IUCN/SSC 2013). The low number of scrub-birds on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner when rediscovered in 1961 suggests that the species likely experienced a major population bottleneck, which may have had significant impact on the genetic diversity of the species through genetic drift or inbreeding (Danks et al. 1996; Cowen et al. 2021). Between 1983 and 1994, as far as practical, birds were sourced from different sub-areas within Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in an attempt to maximise genetic diversity of founder groups (A. Danks, unpubl. data).

In this paper, we summarise and review the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird translocation program that used the population on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve as a source of birds between 1983 and 1999. The effects of removal of scrub-birds from the parent population were monitored and are reviewed here. We also review genetic work in the context of birds from Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve being used as a source for establishment of other subpopulations, and the understanding of song-groups in the context of the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird translocation program. Specifically, we evaluate success in relation to the following aims of the scrub-bird translocation program (Burbidge et al. 1986; Danks et al. 1996):

To provide security for the species in the event of bushfire through the establishment of additional populations to increase population size and geographic spread;

Improve methods and strategies for translocations: including methods to assess suitability of potential translocation sites and to reduce impacts on the source population;

Increase understanding of scrub-bird biology and behaviour to inform any further translocation efforts: through capture, holding, monitoring and telemetry;

Increase understanding of genetic constraints in relation to population bottlenecks, selection of individuals for translocations, and implications for future genetic management; and

Test the significance of song groups and their possible impacts on social relationships during translocations.

Materials and methods

Source population monitoring

The number of singing scrub-bird males is a measure of the number of territories defended during the breeding season and provides a population index. There is no practical method to census female scrub-birds, although some nesting areas are known and can be surveyed to establish annual breeding activity. Complete censuses of singing males have been carried out almost annually at Two Peoples Bay since 1966, using the techniques of Smith and Forrester (1981) and Smith (1985a). A census involves several visits to each territory during the breeding season, both before and after the capture and removal of any birds for translocation has ceased.

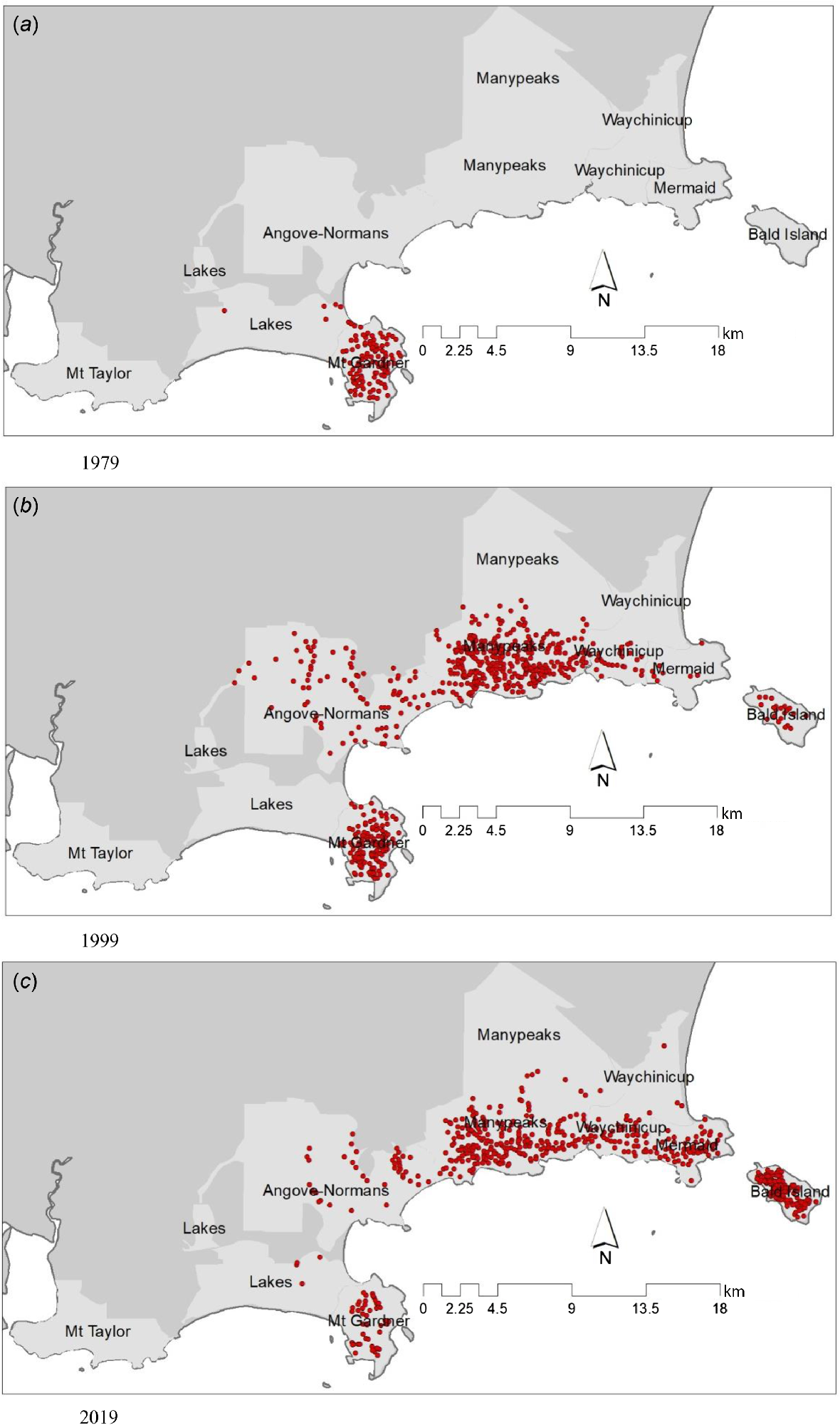

At a population level, the effect of the regular removal of breeding adults was primarily monitored through the annual census of territorial males. As the population expanded, the area of suitable habitat between Two Peoples Bay and Cheynes Beach was divided into sub-areas to facilitate partial census. The area occupied by the single mainland and Bald Island subpopulations is collectively referred to as the Albany Management Zone, with sub-areas on the mainland including Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner, Lakes, Angove-Normans, Mt Taylor, Yilberup/Manypeaks, Waychinicup, Mermaid, and Bald Island (Fig. 4; Danks et al. 1996).

To monitor the replacement of captured territorial males, additional visits were made to territories where males had been removed. This monitoring was often opportunistic, and the more accessible territories received greater attention than others. Some territories were not visited until the next census several months later. In 2006, a translocation from Mermaid to Porongurup National Park provided an opportunity to document the songs of replacement birds which is described in more detail below. Replacement of females captured from nests or nesting areas could be confirmed if the nesting area was used in the following year.

Translocation methods and strategies

Before the trial translocation project, Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds were not routinely captured and it took many weeks of trial and error before techniques for capturing males and females were developed. Graeme Folley, Fisheries and Wildlife Reserve Officer at Two Peoples Bay, led the trial translocation project and Don Merton was seconded from the New Zealand Wildlife Service (now Department of Conservation) to assist, bringing a lifetime’s experience in translocating threatened birds to the project. The third member of the 1983 team was Alan Danks, from Fisheries and Wildlife. An aviary with separate compartments was constructed at Two Peoples Bay so captured birds could be held temporarily before transfer as a small group to the release site. Each compartment was furnished with a layer of leaf litter and shrubs to provide cover for the birds. Male scrub-birds required individual compartments, but two females could be housed together. In captivity the scrub-birds were voracious feeders and keeping them well fed meant gathering and breeding large numbers of live invertebrates. Captured scrub-birds were held at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve for between several days and up to 3 weeks, and fed a diet of mealworms, cockroaches, crickets, and other invertebrates (Danks 1994).

All scrub-birds taken from Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve for translocations between 1983 and 1999 were sourced from Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner and the Lakes sub-areas (Fig. 3). The initial strategy was to translocate large numbers of birds of both sexes; up to 20 each year, ideally with an even sex ratio (Burbidge et al. 1986). In the early 1990s, a more conservative release strategy was introduced, where a small group of males was released in the first year, followed by females and sometimes additional males in the second year if males from the first release had persisted. To ensure that harvesting of founders was from as wide an area as possible, birds were sourced from 10 areas within Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve; eight within the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner sub-area, and two around the Wilson’s Swamp/Tyiurtmiirity/Gardner Creek in the Lakes sub-area (Fig. 4) (A. Danks, unpubl. data). Post-1999, when birds had established, scrub-birds were captured for translocations from Angove-Normans, Bald Island, Mermaid, and Yilberup/Manypeaks sub-areas.

Release site selection

Initial assessment of release site suitability was based on a visual assessment of habitat, and comparison with occupied habitat at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. In later years, more rigorous assessments of translocation sites were undertaken, using release site characteristics described by Danks (1997). This included abundance of leaf litter invertebrates, fire management options, and land tenure and purpose. Understanding of preferred leaf litter invertebrates was based on work at Two Peoples Bay by Danks and Calver (1993) and Welbon (1993). From 1994, the availability of food resources at potential release sites was assessed by sampling leaf litter invertebrates. The abundance of invertebrates was then compared to occupied territories on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner (Danks 1997). Later, other factors such as presence of introduced or native predators, and potential for management and control of feral cats (Felis catus) in particular, were also considered as part of the release site selection, with preference for sites managed under DBCA’s Western Shield Program (Miller et al. 2012; Comer et al. 2020).

Capture methods

Territorial males were captured using a song playback system in conjunction with a modified mist net (Fig. 5). Capture of male scrub-birds was most efficient during the breeding season, and the mist net set-up needed to be within the singing territory to be effective. Between 1983 and 1999, breeding females were captured at their nest (Fig. 6) using a specially designed nest trap. From 2003, females were also captured in mist nets using playback of female calls, with placement of nets in known nesting habitat. Females were only responsive to playback for a short period of time during the early stages of the breeding season. Based on several nests found post-capture, this was believed to be in the latter stages of the 3-week nest-building period and early stages of incubation. In addition, between 1983 and 1992, both males and females (mostly non-breeding) were captured in Elliott mammal traps modified for use with ground dwelling birds by the insertion of a wire mesh end. Elliott traps were used, either in conjunction with a drift fence or placed in tunnels in dense vegetation (Danks 1994). Padded transport boxes were used for transporting scrub-birds from holding aviaries to release sites.

Impacts of translocation on song sharing

The effect of translocation on the song groups of males was studied during a translocation of birds from the Mermaid area near Cheyne Beach to Porongurup National Park in 2006 (Fig. 2). This study focused on what happened to the songs of territorial males sourced from different song groups before and after release in a new area. Methods for determining song groupings, song sharing, and repertoire change in scrub-birds are detailed in Berryman (2003, 2007). The songs of territorial males at the source site (Mermaid) were recorded in the month prior to captures commencing to determine which birds shared songs and belonged to the same song group.

Playback songs used for captures were either from the targeted male, or from neighbours within hearing distance to avoid introducing any novel song material. Once a bird was removed from its territory, checks were made as often as possible to determine when that bird had been replaced, and songs of replacement males were recorded and compared to those of the original territory holder.

In 2006, birds were fitted with transmitters and radio-tracked following release in the Porongurup National Park, and singing was recorded after release. The birds were released at two locations, which were approximately 1.8 km apart (three males at one location, five males at the other). Spectrograms of songs given by individuals were compared over time to study changes in each individual’s songs, and also compared between individuals to determine whether they shared songs or had similarities in their song types, with methods described in Berryman (2007).

Genetics

An assessment of genetic diversity and inbreeding in Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird populations was undertaken by Cowen (2014), who extracted DNA from blood and feather samples collected from birds captured between 1998 and 2011 (Cowen et al. 2021). Using novel species-specific microsatellite loci (Cowen et al. 2013) across 60 individuals from three sub-areas (Two Peoples Bay = 22, Mt Manypeaks/Mermaid = 23, and Bald Island = 15), Cowen (2014) considered a range of metrics, including expected and observed heterozygosity, allelic diversity and richness, intra- and inter-population relatedness and genetic structure, inbreeding coefficient, Wright’s F-statistics, and evidence of population bottlenecks. The full methods used are outlined in Cowen et al. (2013, 2021). Cowen (2014) also investigated diversity in an adaptive gene group linked to immunocompetence and disease resistance: the Major Histocompatibility Complex (Class II B) (MHC).

Translocation success

Translocation success was determined by the number of singing males at the new site exceeding the number released, indicating that breeding had occurred. Radio-telemetry was used from 1990, to provide information on short-term survival and movement to a maximum of 3 weeks post-release. The movement of females could only be monitored using radio-telemetry as they do not sing. Nest searching was impractical in most translocation sites due to the often extensive nesting habitat and lack of well-defined and known nesting areas as are found in gullies at Two Peoples Bay. In addition, the risk of major disturbance to these areas limited the ability to search for nests.

Results

Between 1983 and 2018, 250 Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds (174 males:76 females) were translocated to 13 locations from the Darling Range, 60 km north-east of Bunbury, to Mondrain Island in the Recherche Archipelago (Fig. 2, Table 1). Two Peoples Bay was the major source of birds with 168 birds (110 males:58 females) translocated from this site between 1983 and 1999. Of the 13 release locations, Mondrain Island was considered a conservation introduction as there were no historical or contemporary records of scrub-birds east of the Waychinicup River (A. Danks, unpubl. data). There were also no contemporary or historical records of scrub-birds at Quarram Nature Reserve, Nuyts Wilderness, Bald Island, Jane National Park, or Porongurup National Park, but these locations fall broadly within the historic range of scrub-birds and therefore these were considered population restoration translocations (reintroductions). A number of other translocations were for the purpose of reinforcement in areas where scrub-bird populations were recovering from bushfires, including to the Angove Water Reserve (part of the Angove-Normans sub-area) in 2011, 2012 and 2017, and Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in 2017 and 2018 (Table 1). All other translocations were reintroductions aimed at restoring scrub-birds to their former range.

| Translocation site | Source | Release years | No. of birds (M:F) | Outcome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks | Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve | 1983, 1985 | 31 (18:13) | Success (1988) | |

| Nuyts Wilderness (Walpole-Nornalup National Park) | Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve | 1986, 1987 | 31 (16:15) | Fail (1988) | |

| Quarram Nature Reserve | Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve | 1989, 1990 | 26 (15:11) | Fail (1991) | |

| Mt Taylor (1) | Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve | 1990–1992 | 12 (6:6) | Initial success, (impacted by bushfire, did not persist) | |

| Bald Island | Two Peoples Nature Reserve | 1992–1994 | 11 (8:3) | Success (1997) | |

| Mermaid | Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve | 1992–1994 | 10 (8:2) | Success (1999) | |

| Stony Hill (Torndirrup National Park) | Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve | 1994 | 5 (5:0) | Fail (1995) | |

| Darling Range (eight distinct release areas) | Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, Angove/Normans | 1997–2003 | 80 (60:20) | Fail (2005) | |

| Porongurup National Park | Mermaid | 2006 | 8 (8:0) | Fail (bushfire) (2008) | |

| Mt Taylor (2) | Mermaid | 2007 | 5 (5:0) | Fail (predation) (2008) | |

| Jane National Park | Bald Island | 2010 | 6 (5:1) | Fail (predation) (2008) | |

| Angove Water Reserve | Bald Island, Mermaid | 2011–2012, 2017 | 14 (10:4) | Success (reinforcement) | |

| ‘Lakes’ (Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve) | Bald Island, Mermaid | 2017–2018 | 6 (6:0) | Success (reinforcement) | |

| Mondrain Island | Bald Island, Mermaid | 2018 | 5 (4:1) | Fail (2020) |

A summary of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird conservation translocations to seven sites between 1983 and 1994 is in Table 1 (Danks 1994, 1997; Comer et al. 2010). Of these Mt Manypeaks, Mt Taylor, Mermaid, and Bald Island were regarded as successful but the birds on Mt Taylor subsequently disappeared following a bushfire in 1995 (Comer et al. 2010). These successful translocations were all within 27 km of the source at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve.

There were no additional large areas of suitable habitat in the Albany locale and nearby south coast reserves, and this led to investigation of potential translocation sites in the Darling Range, where the type specimen was collected by Gilbert in 1842. Planning for this reintroduction commenced in 1996 with studies of leaf litter invertebrates, habitat suitability, and discussions with local land managers about fire management, including Alcoa Australia who held mining leases over the area of interest (Danks 2000). Between 1997 and 2003, 80 scrub-birds (60 males and 20 females) were released in eight locations near the historical collection sites at Mt William and Drakesbrook in the Darling Range (Fig. 2). Only one of these locations showed any sign of breeding success, with an unbanded male captured in 2005 (S. Comer et al., unpubl. data). Following the predation of two radio-tracked scrub-birds in 1999, a study of potential predators was carried out in 2000. Black rats (Rattus rattus) were found in scrub-bird habitat at all Darling Range release areas, with high trap rates (up to 5%). Chuditch (Dasyurus geoffroii) were also recorded in all release areas (B. Johnson and L. Cuthbert, unpubl. data). Survey efforts continued in the Darling Range until 2012, but no singing activity has been detected since 2007.

Other translocations in the mid-2000s included the release of eight males in Porongurup National Park between June and August 2006 (Fig. 2, Table 1). While the early signs were promising, with up to four scrub-birds heard calling through to December 2006, the founder males were impacted by bushfire in February 2007. Two birds were heard calling in creek lines outside the park following this fire, but failed to persist. In 2007, a second attempt made to re-establish scrub-birds on Mt Taylor was unsuccessful.

In 2010, a translocation to Jane National Park (Fig. 2, Table 1), near Northcliffe, also failed, most likely due to predation. The remains of two birds were found within 6 days of release. Although not conclusive, both mortalities were believed to be from feral cats with sign of cat activity near one of the carcasses and cat tracks seen around the release site. Of the other four birds released, two could not be located 24 h after release, and the fate of the other two was unknown.

These three translocations (Porongurup National Park, Mt Taylor, and Jane National Park) all sourced birds from areas established through previous translocations (Table 1). Scrub-birds sourced for Jane National Park were from Bald Island; and for Porongurup and Mt Taylor from the Mermaid sub-area.

In 2011, 2012, 2017, and 2018, reinforcement translocations were undertaken to the Angove Water Reserve (Angove-Normans sub-area) and Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve (Fig. 4). These aimed to increase genetic diversity at a local level and enhance the viability of the small numbers of scrub-birds remaining in these locations following fires in the Angove Water Reserve in 2003, and at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in 2015.

In 2018, a trial translocation of five scrub-birds (four males and one female) was undertaken to Mondrain Island in the Recherche Archipelago (Fig. 2). These birds were released on the southern end of the island in July, in the only unburnt habitat following a bushfire early in 2018. The released males continued calling through the summer months and a single short song was heard in April 2019. Surveys of the entire island in 2020 failed to locate any scrub-birds and this translocation is assumed to have failed.

For the translocations from 1994 to 2018, females were only released in areas where males persisted through to the second year, with the exception of Jane National Park and Mondrain Island where a single female was released with four males.

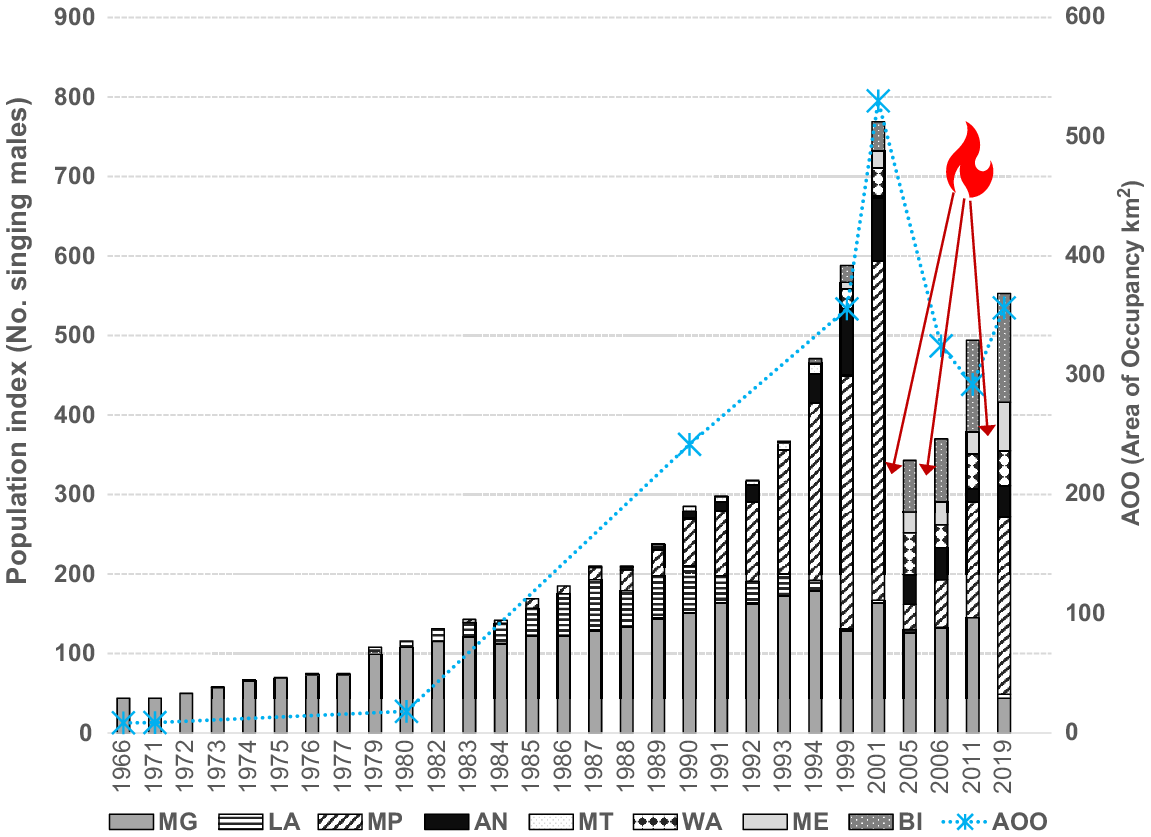

A total of 168 scrub-birds (110 males and 58 females) were removed from the Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve for translocation between 1983 and 1999 (Fig. 7). From 1999 to 2018, 82 scrub-birds (64 males and 18 females) were translocated from Manypeaks, Bald Island, Mermaid, Waychinicup, and Angove-Normans sub areas (Table 1; see Supplementary material Table S1). At the time of capture, the majority of the males were territory holders, whose removal might be expected to directly affect the census of singing males in the year of capture or in subsequent years if they were not replaced. Between 1983 and 1990, the number of singing males within Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve increased annually, despite the removal of birds (Fig. 8).

Territory replacement time

Between 1983 and 1987, detailed records were obtained of the time taken for 32 captured territorial males to be replaced within their territories. Five were replaced within 1 day, four were replaced within 1 week, six were replaced in less than 1 month, 10 were replaced within 6 months, and another six were replaced by the next breeding season. During this period of intensive monitoring of replacement males, only one territory remained vacant after a territorial male was removed in 1985, i.e. 96.9% of the captured territorial males were replaced.

In 1999, the final year of sourcing scrub-birds for translocations from Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, eight males were captured for translocation to the Darling Range (S. Comer and A. Danks, unpubl. data). The replacement rate of singing males in 1999 was noted as very slow, compared with anecdotal records between 1989 and 1998 when most birds were replaced within a few days (A. Danks, unpubl. data). It took between 10 and 131 days for males to reoccupy the six territories where singing males were replaced in 1999, and two other territories were not reoccupied in 1999 (S. Comer and A. Danks, unpubl. data).

Two adjacent territories near Wilson’s Swamp at the Lakes sub-area in Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve (Fig. 4) were trapped more intensively than other territories and because of their accessibility and proximity to the research facilities, these could be monitored more closely. Between 1983 and 1987, 12 males (including nine territorial males) and seven females were removed from these two territories. In each territory, removal of the territorial male was followed by a generally rapid replacement by another male. This occurred five times in both territories. The initial replacement of the two original territorial birds occurred within 24 hours, while later replacements required periods ranging from 2 days to 3 weeks. The replacement males were captured at the same locations as the territorial male they were replacing, suggesting close knowledge of the territory and of the previous territorial male’s movements. Two other territories, adjacent to the Wilson’s territories, were also monitored at the time of the captures in the Wilson’s Swamp area (Fig. 4), and these appeared to retain their territorial males.

In 1986, after capture and removal of the territorial male from one of the two Wilson’s Swamp territories (Fig. 4), the replacement was a young male with a poorly developed song, possibly in his first year. The intensity of the song increased over the next 6 months and eventually became like regular scrub-bird territorial song. After capture of two non-territorial males in a trapline in the same area in 1987, removal of the territorial male resulted in that territory being occupied by the territorial male from the adjacent territory. This male defended both territories until 6 months later when each territory had its own territorial male.

Post-capture monitoring of replacement of territorial males in other sites showed rapid replacement. In 2000, 15 males were captured from the Yilberup/Manypeaks and Angove-Normans sub-areas (Fig. 8). Replacement of males occurred in all but one territory. Eight territories were reoccupied within 1 day, three were reoccupied within 1 week, and two were reoccupied within 3 weeks. At Mermaid, where birds were first removed for translocations in 2006, males were also replaced quickly. Of eight males removed in 2006, four vacated territories had new males calling within 24 hours, two had new males calling within 2 days, and one had a new male calling within 4 days. The remaining Mermaid replacement was a bird that was recorded 17 days after capture, but this was after the second male was removed from this territory within a 5-week period. On Bald Island in 2009 and 2010, most captured males were replaced within 48 hours, but it was more difficult to monitor these areas due to limited time spent on the island.

A total of 28 females were captured at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve between 1983 and 1987. Of these, 22 were considered to be breeding at the time of capture, as they were captured at the nest, had a well-developed brood patch, or an egg in the oviduct when captured. Evidence (from nest searching and trapping in 1985, 1986, 1987, and 1989) suggested there was replacement of at least 12 (54.5%) of these breeding females. Four were found to have been replaced by the following breeding season, three were replaced after 2 years, three were replaced after 3 years, and two were replaced after 4 years. After this 4-year monitoring period, there was no evidence for replacement for 10 of the 22 captured breeding females.

Translocation success

Between 1983 and 2018, scrub-birds were reintroduced to 10 locations including seven sites not considered part of the Albany Management Zone, and one conservation introduction (Mondrain Island). For seven of these translocations, founders were sourced only from Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, and for the Darling Range over 50% of the translocated birds were also sourced from Two Peoples Bay (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1). Two reinforcement translocations were undertaken to two occupied areas within the Albany Management Zone (Table 1). Of 11 translocations to new sites, only four were considered successful: (1) Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks; (2) Mermaid; (3) Mt Taylor; and (4) Bald Island. All were within a radius of 27 km from the source population at Two Peoples Bay (Figs 8 and 9), and all founders for successful translocations came from Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. Four translocations (Nuyts Wilderness, Quarram, Stony Hill, and Darling Range) using founders from Two People Bay were unsuccessful (Table 1).

Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird population index and trend in the Area of Occupancy for years between 1966 and 2019 where a full census was completed, showing the sub-areas (MG, Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner; LA, Lakes; MP, Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks; AN, Angove-Normans; MT, Mt Taylor/Gull Rock; WA, Waychinicup; ME, Mermaid; BI, Bald Island). Major bushfires are indicated between 2001 and 2015.

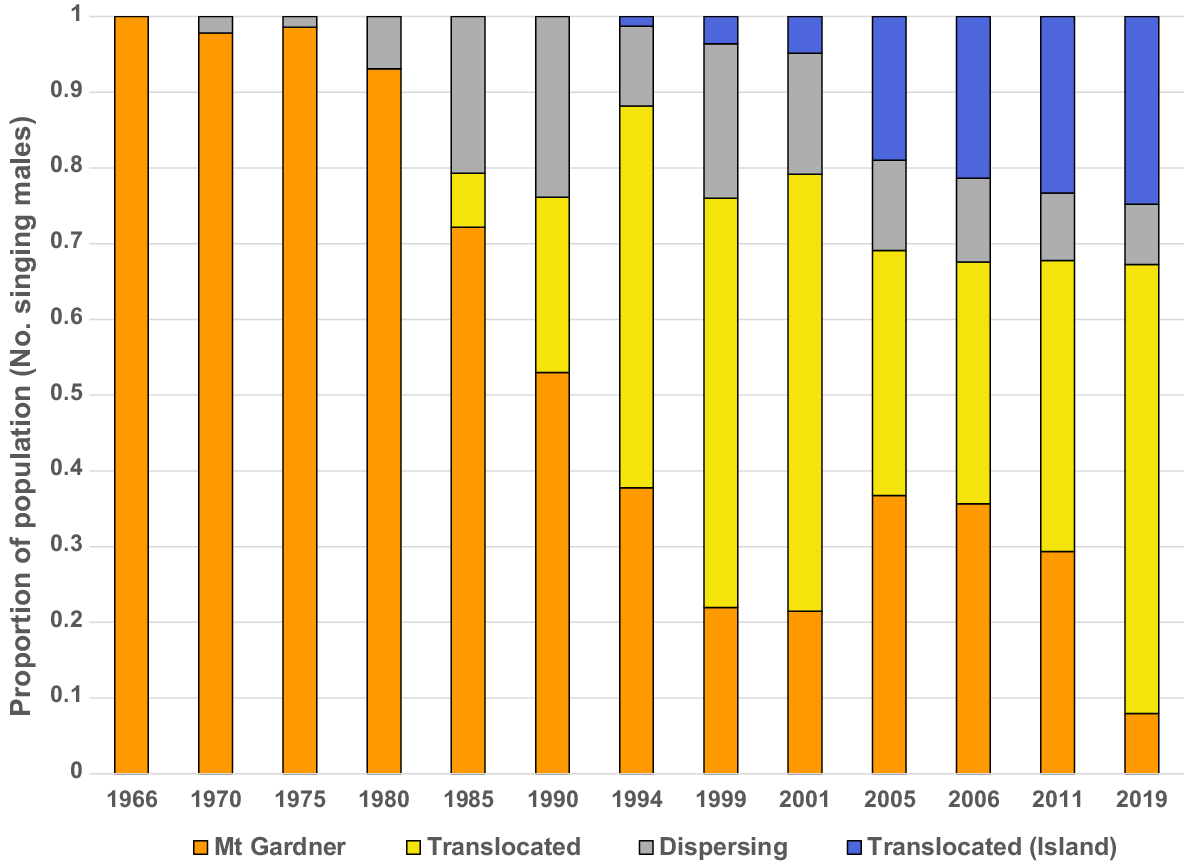

By 1999, it was clear that the Two Peoples Bay population was declining (Figs 7 and 9), and no further scrub-birds were removed from the Reserve. From 2000, the birds were sourced from sub-areas established by previous successful translocations. By 1994, over 50% of the total scrub-bird population was derived from birds translocated from Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. By 2019, the proportion of the population derived from translocated populations had grown to over 90% (Fig. 10). Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds dispersing from Two Peoples Bay in the late 1980s also made a small contribution to the population outside the Reserve (Fig. 10; Danks 1991).

The proportion of the population index (number of territorial males) for the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird population derived from translocations and dispersing birds (estimated), with birds from Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve used to source all translocations up to and including 1999. By 2019, Bald Island and the mainland sub-population was contiguous between Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve derived from the parent population on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner (rediscovered), and Cheynes Beach on the south coast of Western Australia.

Failures of translocations from Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve to Nuyts Wilderness and Quarram Nature Reserve between 1986 and 1990 led to a review of the release strategy, which had focused on translocating large numbers of both males and females. This involved a significant capture effort and a high level of impact on a small source population. Subsequently, small groups of males only were released in the first year to test habitat suitability. This strategy was used in translocations to Mermaid, Mt Taylor, Bald Island, and Stony Hill; the first three of these were successful compared to one out of three successes (Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks was successful) when large groups of founders were released (Danks 1994). The geographic spread of birds following the commencement of the translocation program increased significantly (Fig. 8), with the Area of Occupancy (IUCN Standards and Petitions Subcommittee 2024) increasing from <20 km2 in 1979 to 356 km2 in 2019 (Fig. 9).

Impacts of fire on translocation sites

Over the period of the translocation program, both source and translocated populations have been impacted by bushfires at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve (Dilly et al. 2025), Mt Taylor, Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks (Comer et al. 2005; Comer and Burbidge 2006), and Porongurup National Park. Scrub-birds were well established at Mt Taylor by 1994, but a bushfire in 1995 burnt all occupied habitat and these birds disappeared. A lightning strike in late December 2004 on Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks burnt over 4500 ha of scrub-bird habitat. The translocated population declined substantially from 427 territorial males in 2001 to only 32 territorial birds in this area in 2005 (Fig. 9). This single fire represented a loss of over half of the population (Comer and Burbidge 2006). By the 2019 census of the Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks sub area, this had increased to 223 territorial males. The 2015 fire at Two Peoples Bay resulted in a steep drop in the numbers of scrub-birds in the Reserve (Dilly et al. 2025), which highlighted the importance of previous translocations, and raised consideration of reinforcing the Two Peoples Bay sub-area from other successful translocation sites.

Angove Water Reserve (in the Angove-Normans sub-area), derived from scrub-birds dispersing from Two Peoples Bay in the late 1980s, was burnt in a bushfire in 2001 and again in 2003. Following the detection of a small number of birds in this area in 2009, additional birds were released as part of reinforcement of this area in 2011, 2012, and 2017 (Table 1).

Song groups and translocation

At Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner, the original source for Mermaid, scrub-birds had discrete song groups with no song types shared between groups. In contrast, the song groupings at Mermaid were not discrete and there was some overlap in shared songs between neighbouring groups. Replacement of males removed from Mermaid for translocation in 2006 was rapid, with most birds replaced within 1–2 days. Seven of the replacement males sang songs the same as the original territory holder, and the remaining male sang the songs of the neighbouring song group (Table 2).

| Territory no. | Captured | Replaced | Song group of replacement male | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 22 June 2006 | 4 days | Neighbouring | |

| 23 | 22 June 2006 | 2 days | Same | |

| 17 | 22 June 2006 | 2 days | Same | |

| 27 | 25 June 2006 | 1 day | Same | |

| 24 | 17 July 2006 | 1 day | Same | |

| 29 | 19 July 2006 | Same day | Same | |

| 27 | 25 July 2006 | 1 day | Same | |

| 23 | 31 July 2006 | Within 17 days | Same |

Males that were released together at Porongurup National Park did not have any song types in common. Radio-tracking of translocated birds was challenging, and a manufacturer error meant that transmitters had either come off the bird or were non-functional by the time the birds began to sing territorial song, so it was not possible to confirm the identity of singing birds. However, in general, enough of each bird’s unique song characteristics were retained to be reasonably confident in assigning his identity (Fig. 11).

Spectrograms of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird 06M05’s pre-capture (Mermaid) and post-release (Porongurup National Park) songs with similarities highlighted. Each spectrogram shows a separate song type, with time on the x-axis and frequency on the y-axis to provide a visual representation of the patterns of each song.

Six of the eight males were recorded singing following translocation, with the time taken to sing territorial song ranging from singing the same day as release, to 50 days post-release. Repertoire size had decreased on average 67% when birds first began to sing, and notably two of the males were singing only a single song type. This is uncommon as a repertoire is usually around five song types (Berryman 2007). Singing was infrequent, and some songs lacked the complexity of those sung pre-capture. Repertoire size subsequently increased over 1–3 months back to levels similar to pre-capture in most birds (Table 3). Monitoring of songs was not possible beyond 7 months post-release because the site was impacted by bushfire.

| Bird ID | Mermaid | Porongurup | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-capture | Initial post-release | Maximal post-release | ||

| 06M01 | 6 | 3 | 8 | |

| 06M02 | 5 | 1 | 5 | |

| 06M03 | 8 | 3 | 7 | |

| 06M04 | 11 | 6 | 5 | |

| 06M05 | 10 | 4 | 4 | |

| 06M06 | 5 | 1 | 3 | |

| 06M07 | 11 | – | – | |

| 06M08 | 6 | – | – | |

Scrub-birds 06M07 and 06M08 were not heard singing post-release, but it is possible that they moved away from the release sites and their singing was not detected. Monitoring was only possible for 7 months post-release, after which the site was impacted by a bushfire.

In three cases, two males that had no song types in common prior to capture were observed to have shared song types when they eventually commenced singing following release. This happened relatively quickly, with shared repertoires apparent within 2 months or less. Lack of consistent singing post-release made it difficult to follow the process of how these birds arrived at a shared repertoire. It is interesting to note that although the main body of shared song types matched, some birds retained their original terminal flourishes (Figs 12 and 13), and this allowed individuals to be identified in the absence of functional transmitters.

Spectrograms of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird 06M02’s pre-capture repertoire (Mermaid) compared with the single song type when he first began to sing at Porongurup National Park. Although this song appears quite different to any of the song types in his pre-capture repertoire it has an identical ending to one of his original song types (highlighted in grey).

Spectrograms showing post-release convergence in the songs of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds 06M04 and 06M02. Similar songs have been placed on the same row. The main phrase of each of the three different song types is near identical but each bird has retained its characteristic endings.

It was not possible to study the longer-term impacts of translocation on song sharing because a bushfire burnt almost the entire area of Porongurup National Park just over 7 months after release.

Genetic management and translocations

Genetic analysis using microsatellites found that measures of genetic diversity were generally low in all three sub-areas (Cowen et al. 2021). Scrub-birds from Two Peoples Bay had the highest allelic diversity but, despite the relatively small numbers of birds translocated from Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve to Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks/Mermaid and Bald Island, genetic diversity (as measured by observed heterozygosity) did not differ significantly between these sub-areas (Fig. 14). Expected heterozygosity was significantly higher than observed heterozygosity in the Two Peoples Bay and Mt Manypeaks/Mermaid sub-areas, which may be indicative of inbreeding. However, inbreeding coefficients (F) did not reflect this (Fig. 14).

The Albany Management Zone indicating pathways of successful translocations between 1983 and 1993 (solid arrows) and dispersal (dashed arrows) of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird, numbers of founders used and measures of genetic diversity (HE (expected heterozygosity) and HO (observed heterozygosity)) and inbreeding (inbreeding coefficient, F).

Furthermore, the microsatellite study found evidence that founder effects from these translocations led to significant differentiation between the Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks/Mermaid and Bald Island sub-areas. Bald Island (established from only 11 individuals, including three females) had the highest levels of relatedness and inbreeding (inbreeding coefficient (F), Fig. 14). Surprisingly, modelling of population bottlenecks had equivocal results, within only Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks predicted to have undergone a bottleneck. Despite little evidence of genetic structure, there was evidence of potential cryptic population substructure (Wahlund Effect; Garnier-Géré and Chikhi 2013), where related individuals are spatially clustered within a putative genetic population. This result was speculated to be due to overlapping sub-areas in an apparently long-lived species. In contrast to the results of the microsatellite analysis (Cowen et al. 2021), there was considerable diversity in functional sequences in the MHC Class II B, which showed evidence of balancing selection, indicating that this diversity had not arisen by chance, but through some evolutionary process, e.g. an unknown pathogen or some behavioural mechanism. However, this process remains a mystery.

Discussion

Since translocations commenced 40 years ago, there has been the development of a larger, more geographically spread population of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird, consisting of mainland and Bald Island subpopulations. The mainland subpopulation has withstood the impacts of two major bushfires in the past 20 years (Comer et al. 2005, 2018). Compared with an estimated 45 territorial males in the rediscovered population at Two Peoples Bay in 1962 (Smith and Forrester 1981), more than 550 territorial males were recorded in the last full census in 2019, with most of these derived from translocations. In 2019, the mainland subpopulation extended from Two Peoples Bay to Cheynes Beach, spanning a distance of 25 km, plus an established subpopulation on Bald Island. All were derived from the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner population in Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. In the 2019 census, the greatest numbers of scrub-birds were on Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks and Bald Island. At the same time, as a result of the 2015 bushfires, fewer than 50 territorial males were detected at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve.

After translocations to 13 sites between 1983 and 2018, which included reinforcements at Angove-Normans and the Lakes sub-areas, the population is still restricted to an Area of Occupancy of less than 350 km2 in the Albany Management Zone. Birds did not establish at nine of these sites, with bushfire and predation among the causes of failure. In spite of these failures, and combined with three significant bushfires, the scrub-bird population index was over 550 territorial males in 2019, representing a four-fold increase since the commencement of translocation program.

During the 1990s, the rate of growth of the population on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner appeared to slow. There was no obvious correlation between the annual census results and the number of birds removed (Roberts et al. 2020). The decline was localised and well away from areas where scrub-birds had been trapped in years immediately preceding the decline. In the years of sourcing birds for translocation from Two Peoples Bay, territorial males were generally observed to be replaced quickly by another male singing territorial song, at least in those territories where frequent checking was possible. However, many territories could not be checked until the next census and this would over-emphasise the ‘6 months’ and ‘next year’ categories. In the latter years of the program, it became harder to monitor the replacement of males, partially due to lack of resources and access to capture sites (e.g. Bald Island), but also the extended time for a replacement male to start calling.

Sequential trapping of males in territories in Wilson’s Swamp indicated the presence of a number of non-territorial males, within or associated with these territories, who were capable of taking over the territorial male’s role after his removal. The residential status of these males could not be positively determined, but the pattern of replacement strongly suggests that they were resident in the territories. Certainly, the inheritance of a territory by a very young male after removal of nine territorial males between 1983 and 1986 would have been unlikely if good numbers of dispersing males were present in the area. Later work studying the removal of males for translocation from the Mermaid sub-area showed that seven of eight males were replaced by males singing the same set of song types, and one replacement male sang the songs of the neighbouring song group, indicating that the replacement males were resident in the area (Berryman 2007).

The presence of non-territorial males in scrub-bird territories was first noted in 1975 (Smith 1985b) and observations during the translocation program confirmed this. However, the number of non-territorial males that could be successively removed from some territories was surprising, suggesting this particular habitat found in the Tyiurrtmiirity/Gardner Creek areas around Wilson’s Swamp at the foot of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner was highly favourable. One non-territorial male that died during the capture program had active gonads (R.E. Johnstone, pers. comm.), which along with the rapidity of replacement of captured territorial males, suggests that these extra males are important in ensuring the continuity of breeding within a territory. In future, the use of autonomous recording units to document replacement time would allow for effective monitoring of replacement in all capture sites, even in remote locations. The rapid replacement also suggests that there may be more males present in an area than indicated by the census of singing males.

The extent and rate of replacement of captured females was much more difficult to determine since it depended largely on finding active nests in the years following capture. However, replacement of breeding females seems to be slower than for territorial males. In practice, nest searching was limited to areas of nesting habitat that could be searched effectively with minimal disturbance to habitat and confined to a particular period within the winter breeding season. In addition, given the difficulty in locating females and finding nests, lack of success does not necessarily mean there was no active nest or female present. These factors create problems in observing the number of breeding females replacing those captured. Although a little more than half of the nesting areas searched on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner were reoccupied the following year, this is likely to be an underestimate. The continued growth in the population index at Two Peoples Bay to 1994, despite removal of males and females over a number of years, suggests that over this period most breeding females were replaced after removal.

Capturing females for translocation proved to be much more difficult than sourcing males, and removing breeding females from a source population was likely to have a greater impact on the source. Changing the release strategy to using only males in the first year to test new translocation sites was likely to have minimised the impact of removals on the source population by not removing breeding females unless there was confidence the release site was suitable, but also allowed for more release sites to be tested (Danks 1994; Kemp et al. 2015). While the monitoring of territorial male scrub-birds on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner was continuous, it proved much more difficult to monitor the number and success of nesting females. The female invests more than 6 months each year in reproduction, from nest-building through to independence of the juvenile. The rapid increase in the population index at Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks and Bald Island suggests very high chick survival rates, a testament to the investment of the female (A. Danks and S. Comer, unpubl. data). This highlights the value of females to both source and new populations, and as such is further support for the ‘testing’ of habitat with only males. Consequently, removing a small number of male birds initially and only translocating females once there was more confidence that they might persist at the new site was a significant improvement to the translocation program (Danks 1994, 1997). This change in strategy also addressed some of the challenges in directing resources to translocations and ensuring that the high cost of implementing translocations is justified (Berger-Tal et al. 2020). In addition, moving small numbers of birds to sites where they may not survive to ‘test’ the habitat suitability addresses some clashes of ethical values where survival is not guaranteed but is a trade-off with the value of establishing new populations for the benefit of the species (Thulin and Röcklinsberg 2020).

Prior to 2006, no consideration was given to the possible significance of song groups in Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird translocations. The sample size in the 2006 translocation to the Porongurup National Park was too small to test if song group source affected translocation success. It was found that males from different song groups (i.e. no shared song types) altered their songs so they shared repertoires with their new neighbours within 1–2 months after release. Repertoire size and amount of singing were also observed to decrease following release, but these too began to normalise within a few months. The degree of song sharing and rapidity with which they changed their repertoire is unusually high for songbirds (Audet et al. 2023) and deserves further study.

The ability of scrub-birds to rapidly alter their repertoires, and the observed formation of new song groups following translocation by males that did not share songs prior to capture suggests that song group source/familiarity of founders is unlikely to have much impact on the success of the translocation. The effects of translocation on song sharing, song output, and repertoire size appear to be short-term, with males forming new song groups and regaining their repertoire size within months of release. Longer-term monitoring of the songs of the translocated scrub-birds was not possible because the translocation site was burnt in a bushfire 7 months after release, and prior to the release of females.

The presence of extensive song sharing and repertoire change (Berryman 2003, 2007) suggests that male scrub-birds are capable of learning their songs from their neighbours on an ongoing basis. However, the observed rapid replacement of birds suggests young male scrub-birds are likely to remain near their natal territories, so genetic studies would be helpful to establish the relatedness of males within a song group. If it can be demonstrated that males that share songs have a high level of genetic relatedness, then selecting males from different song-groups could ensure the translocation of related individuals is minimised. However, this type of investigation would require use of genetic analyses that could be conducted quickly.

To ensure that translocated populations are genetically representative of their source populations, managers are advised to maximise the size of the founder cohort (Weeks et al. 2015). However, in the case of the scrub-bird, the difficulty in capturing individuals represents a major constraint and small founder groups are preferred to minimise the impact on a small source population. Despite this, the two extant translocated sub-populations, Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks/Mermaid and Bald Island successfully established, and their genetic diversity was not found to be significantly lower than that of the source population at Two Peoples Bay (Cowen et al. 2021). This is indicative of the generally low genetic diversity in the species, likely due to its range contraction to Two Peoples Bay and decline to an estimated 45 territories in 1962. It is probable that the lack of significant difference in genetic diversity between the source and the two translocated populations sampled is the result of the capture strategy where birds were deliberately sourced from 10 different areas at Two Peoples Bay. However, Bald Island, founded with just 11 individuals, has the highest levels of inbreeding and relatedness. The impact of low genetic diversity and inbreeding may be cryptic (Taylor et al. 2005), and we should not be complacent about the need to augment genetic diversity in all three populations.

Genetic management through reinforcements has already commenced (Angove and Lakes in 2017–2018). Furthermore, the devastating bushfire on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in 2015 (Dilly et al. 2025) has led to a potential need for reinforcement from translocated populations (highlighting their critical importance) in order to maintain a viable population. While there have been some valuable lessons from genetic work on the scrub-bird, some important questions remain. For example, given that the species may have been vulnerable to fragmentation caused by fire during its evolutionary history, how does contemporary genetic diversity compare to that of specimens collected shortly after European colonisation? Additionally, the original work by Cowen (2014) was limited by molecular techniques that have advanced considerably in the past 10 years and alternatives to microsatellites (e.g. single-nucleotide polymorphisms) may provide greater statistical power and confidence in the results of genetic analyses. The intriguingly high diversity in MHC Class II B indicated this adaptive gene was under selection and the mechanism by which this may have occurred also merits further investigation.

Founder group sizes for scrub-bird translocations were mixed, with success from a founder group of 31 birds on Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks, but only 11 on Bald Island. While the size of these founder groups is less than desirable due to the potential for inbreeding and loss of genetic diversity, translocation of large numbers of individuals was not feasible due to the importance of testing release areas, potential impacts on the source population, practicalities of capturing large numbers of birds and resource limitations (Danks 1997; Comer et al. 2010; Kemp et al. 2015; Cowen et al. 2021). In spite of the low numbers of birds used to establish new populations, there was no evidence to suggest that allelic diversity, heterozygosity, or inbreeding has been significantly affected in any sub-area or population (Cowen et al. 2021). However, future translocations will require guidance to ensure genetic diversity is maximised.

Conclusion

As the Western Australian human community heads towards commemorations of 200 years since European colonisation of the state, there have been a number of remarkable conservation success stories using translocations to address the dramatic decline of native species post-colonisation (Burbidge and McKenzie 1989; Morris et al. 2015). The significance of the translocation program for the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird is one of these, and is notable in having ensured that this unique songbird has a future. In addition, the translocation program has contributed to conserving Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird, a species of evolutionary importance and cultural significance for Traditional Custodians of the Two Peoples Bay area (Comer et al. 2018; Knapp et al. 2024). Recent monitoring of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in 2024 (S. Comer et al. unpubl. data) demonstrated the value of creating multiple populations: with only eight territorial males remaining in the reserve after the 2015 fire, the prospects for the long-term viability of scrub-birds in this area would have been catastrophic without the existence of the translocated subpopulations. Conservation translocations have been instrumental in securing and conserving the scrub-bird, with considerable spatial expansion of the species range (now with over 550 territorial males spread across several sites), in spite of significant bushfires impacting habitat. Despite this success, the scrub-bird still remains restricted in geographical range, with an Area of Occupancy of less than 350 km2 and only two effective sub-populations. With the likelihood of unplanned fire increasing, and climate change likely to modify suitable habitat, maximising the number of geographically distinct populations remains a priority for the conservation of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird.

Data availability

The data that support this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest

Graeme T. Smith died in 1999. He had no known conflicts of interest, nor do the living authors of this paper.

Declaration of funding

Funding support for translocations and census was provided through Western Australian Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions and its predecessors, Commonwealth Government (Saving Native Species, Natural Heritage Trust), South Coast NRM, and BirdLife Australia.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Minang, Wudjari, and Whadjuk people on whose country translocations of Djimaalap have occurred, and the Merningar Bardock as the Traditional Custodians of Two Peoples Bay. A. Danks and G.T. Smith were authors of a paper that examined the removal of scrub-birds from Two Peoples Bay between 1983 and 1987, written for a special bulletin of CALMScience devoted to the natural history of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. This paper was subject to peer review, revised, and accepted for publication in 1991. The special bulletin was never published. By the time the papers collected for the special bulletin were collated in order to publish them over 30 years later in the special collection of Pacific Conservation Biology, author G.T. Smith had died. We have incorporated some of the material on replacement of territorial males from the original Danks and Smith paper into this manuscript and included G.T. Smith as an author. We thank reviewers Professor John Craig and Dr Jacqui Richards whose comments significantly improved this manuscript, and the review and support of Dr Denis Saunders, the Guest Editor of the Pacific Conservation Biology collection on The Natural History of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. The first translocations of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds were carried out under the direction of Graeme Folley and Don Merton, and we acknowledge their contribution to conservation of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds. The South Coast Threatened Birds Recovery Team continues to guide the implementation of the South Coast Threatened Birds Recovery Plan, and we thank the members of this team for their ongoing support. We thank the many people who were involved in the translocation and Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird conservation work between 1983 and 2024, and have contributed to the results presented here. Special mention to Otto Mueller, Peter Cale, Ian Wheeler, Allan Rose, Leigh Whisson, Lawrence Cuthbert, Kim Williams, Bruce Withnell, Shapelle McNee, Josie Dean, Tony Bush, Joan Bush, Melissa Danks, Peter Speldewinde, Neal Henshaw, Jennifer Langton, Geoff Harnett, Wes Manson, Dave Chemello, Dave Wilson, Peter Masters, Cameron Tiller, Ron Sokolowski, Graeme Folley, Jeff Pinder, Jon Pridham, Mark True, Neil Scott, Deon Utber, and Abby Martin for their contributions to the recovery of the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird. We also thank the many managers and rangers of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve and surrounds, who have continued to support fire management, management of introduced predators and the Djimaalap/Noisy Scrub-bird recovery program. Pat Maslen and Abby Martin have assisted with the development and curation of the geospatial database used to manage census data.

References

Audet J-N, Couture M, Jarvis ED (2023) Songbird species that display more-complex vocal learning are better problem-solvers and have larger brains. Science 381, 1170-1175.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Baird RF (1991) Holocene avian assemblage from Skull Cave (AU-8), south-western Australia. Records of the Western Australian Museum 15, 267-286.

| Google Scholar |

Berger-Tal O, Blumstein DT, Swaisgood RR (2020) Conservation translocations: a review of common difficulties and promising directions. Animal Conservation 23(2), 121-131.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Berryman A (2007) Song sharing and repertoire change as indicators of social structure in the noisy scrub-bird. Ph.D. thesis, Murdoch University, Perth, WA. Available at http://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/473/

Bock WJ, Clench MH (1985) Morphology of the noisy scrub-bird, Atrichornis clamosus (Passeriformes: Atrichornithidae): systematic relationships and summary. Records of the Australian Museum 37, 243-254.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Burbidge AA, McKenzie NL (1989) Patterns in the modern decline of Western Australia’s vertebrate fauna: causes and conservation implications. Biological Conservation 50(1-4), 143-198.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Burbidge AH, Comer S, Danks A (2018) Collaborative commitment to a shared vision: recovery efforts for noisy scrub-birds and Western Ground Parrots. In ‘Recovering Australian threatened species. A book of hope’. (Eds S Garnett, P Latch, D Lindenmayer, J Woinarski) pp. 95–104. (CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, Vic)

Chatfield GR, Saunders DA (2024) History and establishment of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. Pacific Conservation Biology 30, PC24004.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chesser RT, ten Have J (2007) On the phylogenetic position of the scrub-birds (Passeriformes: Menurae: Atrichornithidae) of Australia. Journal of Ornithology 148, 471-476.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Christidis L, Norman JA (2010) Evolution of the Australasian songbird fauna. Emu - Austral Ornithology 110(1), 21-31.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Comer S, Burbidge AH (2006) Manypeaks rising from the ashes. Landscope 22(1), 51-55.

| Google Scholar |

Comer S, Danks A, Burbidge AH (2005) Noisy scrub-birds, Western Whipbirds and fire at Mt Manypeaks. Western Australian Bird Notes 113, 16-17.

| Google Scholar |

Comer S, Danks A, Burbidge AH, Tiller C (2010) The history and success of noisy scrub-bird re-introductions in Western Australia: 1983-2005. In ‘Global re-introduction perspectives: additional case-studies from around the globe. (Ed. PS Soorae) pp. 187–192. (IUCN/SSC Re-introduction Specialist Group: Abu Dhabi)

Comer S, Danks A, Berryman A, Cowen S (2018) Living on the edge: the survival of the noisy scrub-bird. Landscope 33, 28-33.

| Google Scholar |

Comer S, Clausen L, Cowen S, Pinder J, Thomas A, Burbidge AH, Tiller C, Algar D, Speldewinde P (2020) Integrating feral cat (Felis catus) control into landscape-scale introduced predator management to improve conservation prospects for threatened fauna: a case study from the south coast of Western Australia. Wildlife Research 47, 762-778.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cowen SJ (2014) An assessment of genetic diversity and inbreeding in the noisy scrub-bird (Atrichornis clamosus) using microsatellite and Major Histocompatibility Complex loci. PhD Thesis, Curtin University, Perth, WA. Available at https://espace.curtin.edu.au/handle/20.500.11937/2293

Cowen SJ, Allcock RJN, Comer SJ, Wetherall JD, Groth DM (2013) Identification and characterisation of ten microsatellite loci in the noisy scrub-bird Atrichornis clamosus using next-generation sequencing technology. Conservation Genetics Resources 5, 623-625.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Cowen SJ, Comer S, Wetherall JD, Groth DM (2021) Translocations and their effect on population genetics in an endangered and cryptic songbird, the noisy scrub-bird Atrichornis clamosus. Emu - Austral Ornithology 121, 33-44.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Danks A (1997) Conservation of the noisy scrub-bird: a review of 35 years of research and management. Pacific Conservation Biology 3, 341-349.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Danks A (2000) The noisy scrub-bird in the darling range. Western Wildlife 4(3), 1-20.

| Google Scholar |

Danks A, Burbidge AA, Burbidge AH, Smith GT (1996) Noisy scrub-bird recovery plan. Western Australian Wildlife Management Program No. 12. Dept of CALM, Wildlife Management Program No. 12. Department of Conservation and Land Management, Como, WA. Available at https://library.dbca.wa.gov.au/static/Journals/080079/080079-02.pdf

Danks A, Calver MC (1993) Diet of the noisy scrub-bird Atrichornis clamosus at Two Peoples Bay, south-western Western Australia. Emu - Austral Ornithology 93, 203-205.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Danks A, Burbidge AA, Coy NJ, Folley GL, Sokolowski RES (2024) Management of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve from 1967 to 1999. Pacific Conservation Biology 30, PC24076.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Department of Parks and Wildlife (2014) South coast threatened birds recovery plan. Western Australian Wildlife Management Program No. 44. Department of Parks and Wildlife, Perth, WA. Available at: http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/resources/52c306c7-9085-4b62-a1dc-4d98c6ebae41/files/south-coast-threatened-birds-2014.pdf