Booderitj/western bristlebird and Dading/western whipbird: ecology and management of two of the lesser-known threatened species at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, Western Australia

Allan H. Burbidge A * , A. Danks

A * , A. Danks  B , S. Comer

B , S. Comer  C and G. T. Smith D †

C and G. T. Smith D †

A

B

C

D

† Graeme T. Smith, deceased June 1999. G. T. Smith was the author of ‘The ecology of rare birds’ and ‘Habitat of rare birds’, concerning bristlebirds and whipbirds (and scub-birds), and which were written for a special bulletin of on the natural history of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, but which was never published.

Handling Editor: Mike Calver

Abstract

While the Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, Western Australia was established for conservation of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird, the reserve also supports other threatened species including Booderitj/western bristlebird and Dading/western whipbird.

This paper summarises and reviews work done at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve on Booderitj/western bristlebird and Dading/western whipbird over the past five decades.

We used occurrence and observational data collected in the field, built on published and unpublished historical data and notes.

Although these two species occur in scattered locations across the Reserve, the stronghold is across the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland, but with different habitat requirements. In the absence of fire, home ranges have been highly constant across several decades. Song types in Booderitj/western bristlebirds are complex and variable, as is their social system, but these observations are difficult to interpret because the cryptic nature of the species makes it difficult to follow individual birds. Both species are sensitive to fire, but with different responses from each other and the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird.

More research is needed to understand the significance of the limited observations on song production and social behaviour. Fire management will be of increasing importance as the south coast climate continues to become warmer and drier.

Fire management of the Reserve needs to consider the different requirements of each of the threatened bird species. No single fire regime is likely to support all three threatened bird species unless it retains sufficient temporal and spatial complexity to do so.

Keywords: bristlebirds, Dasyornis, endangered, fire management, Psophodes, territory/home range variation, threatened birds, whipbirds.

Introduction

As human impacts become more pervasive and intensive, the rate of change in natural ecosystems is escalating (Steffen et al. 2007). Threats to many species are growing as reflected in the rapid deterioration of broad measures of biodiversity health increasingly observed (Ceballos et al. 2017; Ward et al. 2019; Murphy and van Leeuwen 2021). In this context, baseline knowledge of the biology, ecology, and behaviour of threatened species is becoming increasingly important for timely and effective conservation management. This is particularly the case in hotspots of biodiversity, such as south-western Australia (Myers et al. 2000), especially on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve where at least 12 threatened species of birds, mammals, fish, invertebrates, and plants occur as breeding species (Orr et al. 1995; Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions 2024; Hopkins et al. 2024a; Hopper et al. 2024; Halse and Storey 2025), introduced predators are challenging to manage (Comer et al. 2020a), and climate change is resulting in a drier climate where fire management is increasingly challenging (Danks et al. 2024; Dilly et al. 2025).

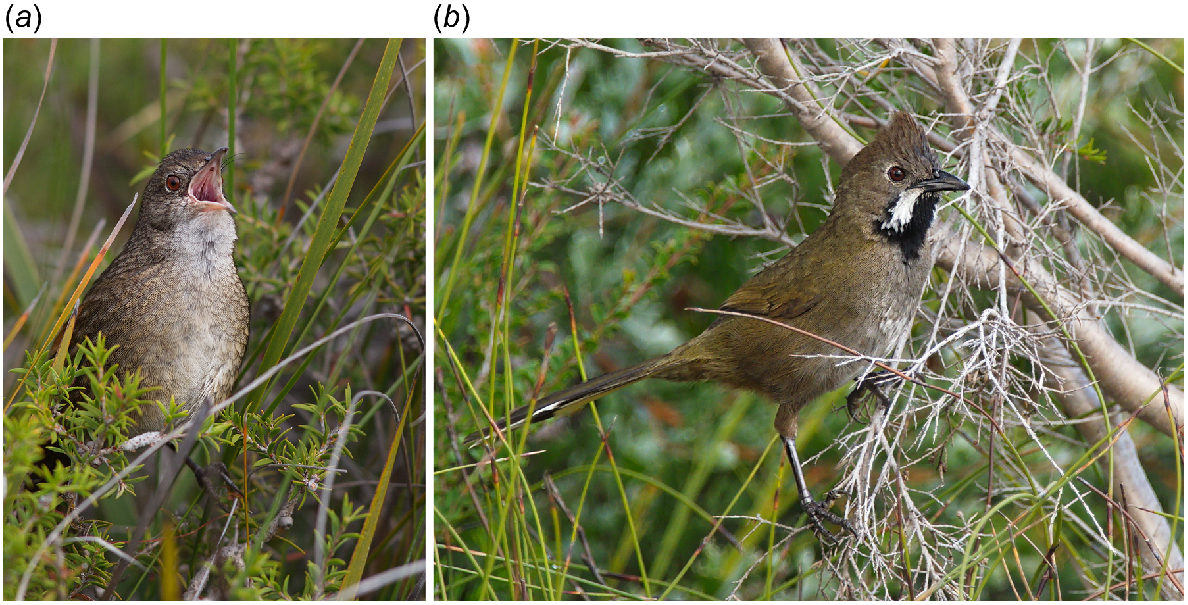

Buller (1945) ‘rediscovered’ the Booderitj/western bristlebird Dasyornis longirostris at Two Peoples Bay when the species had not been seen with certainty for almost 40 years, and there was speculation that it may have become extinct. Thus began ornithological interest in Two Peoples Bay, leading to J. R. Ford collecting bristlebirds (and looking for Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird, Atrichornis clamosus) in the area in late 1961 (Burbidge and Russell 2018). The announcement of the rediscovery of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird at Two Peoples Bay (Webster 1962) focused considerable attention on this area (Danks et al. 2011; Burbidge and Russell 2018; Chatfield and Saunders 2024), later leading to recognition of other high conservation values of the region. At Two Peoples Bay, this extra attention focused initially on the Booderitj/western bristlebird and Dading/western whipbird Psophodes nigrogularis (Fig. 1). Currently, these three species are each declared threatened under the Western Australian Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 and under the Australian Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999: the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird and Booderitj/western bristlebird are listed as Endangered, as is the local subspecies of the Dading/western whipbird. (Noongar names for bird species follow Abbott (2009) and Knapp et al. (2024) and are given before the European names. Where known, place names at Two Peoples Bay follow Knapp et al. (2024)).

(a) Booderitj/western bristlebird at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve and (b) Dading/western whipbird photographed near Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks. Photographs: Alan Danks.

The genera Atrichornis, Psophodes, and Dasyornis are members of the ancient endemic Australian passerine avifauna (Bock and Clench 1985; Sibley and Ahlquist 1985; Oliveros et al. 2019) and were probably present in the late Oligocene-early Miocene, prior to Australia connecting with Asia in the Miocene (Moyle et al. 2016; Oliveros et al. 2019). Both the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird and Dading/Western whipbird in Western Australia have a closely related congenitor in eastern Australia, while the Booderitj/western bristlebird has two in eastern Australia and one (extinct) in Western Australia.

Together with the habitat requirements and presumed antiquity of the three genera, this distribution pattern suggests that their ancestors had a wider, trans-Australian distribution in the past (Smith 1977). The changes in climate and the concomitant vegetation changes from the Miocene onwards, especially the relatively rapid climatic oscillations during the Pleistocene (Galloway and Kemp 1981; Kemp 1981; Ogg and Pillans 2008; Crucifix 2012), led to a contraction of the distributions that resulted in small, relict populations with disjunct distributions. In Western Australia, this was more pronounced for the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird and Booderitj/western bristlebird, which are older and more conservative species than the Dading/western whipbird (Oliveros et al. 2019), which may have been better adapted to the cyclical environment (Smith 1977; Schodde 1982).

When Europeans first settled in Western Australia in 1826, Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds, Dading/western whipbirds, and Booderitj/western bristlebirds were more abundant and widespread than they are today. All three species are terrestrial and sedentary with weak powers of flight, characteristics that suggest that their powers of dispersal are poor. These attributes, together with a low reproductive potential, made them vulnerable to the environmental changes caused by Europeans (Smith 1977). These species were so vulnerable that they were each thought by many to be extinct when they had not been recorded for some decades in the early 20th century (Whittell 1939).

Today, all three species are confined to a small number of isolated localities in the less populous areas of the south-west. Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve is the most important of these because it, and the nearby Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks/Waychinicup complex, is the only locality that is managed specifically for all three species. In addition, its topography provides protection against fire, which is the major potential threat to the species.

Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve is the only area in which the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird is known to have survived since its decline in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but the Booderitj/western bristlebird and Dading/western whipbird are found in a number of other localities. The Reserve is clearly important for all species, but the priority for management has been the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird because of its perilous situation and enigmatic nature, resulting in more detailed work being done on this species (Comer et al. 2025; A. Danks, S. Comer, unpubl. data). Fortunately, in the early 1970s when the Western Australian Department of Fisheries and Fauna asked CSIRO to study the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird, it was agreed that they would also take the opportunity to study the Booderitj/western bristlebird and Dading/western whipbird. Here, we summarise and review the ecology of the Booderitj/western bristlebird and Dading/western whipbird, with reference to what is known from Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. This information has formed part of the data required for the development of management plans and policies for Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, and continues to inform development of species recovery actions (Department of Parks and Wildlife 2014).

Materials and methods

The following account is based primarily on observations at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve from 1971 to 1982 (Smith 1987a). Smith and colleagues from CSIRO spent long times in the field, and the current account is based on their published and unpublished notes, augmented by many observations and investigations made by A. Danks, S. Comer, A. H. Burbidge, and others since then.

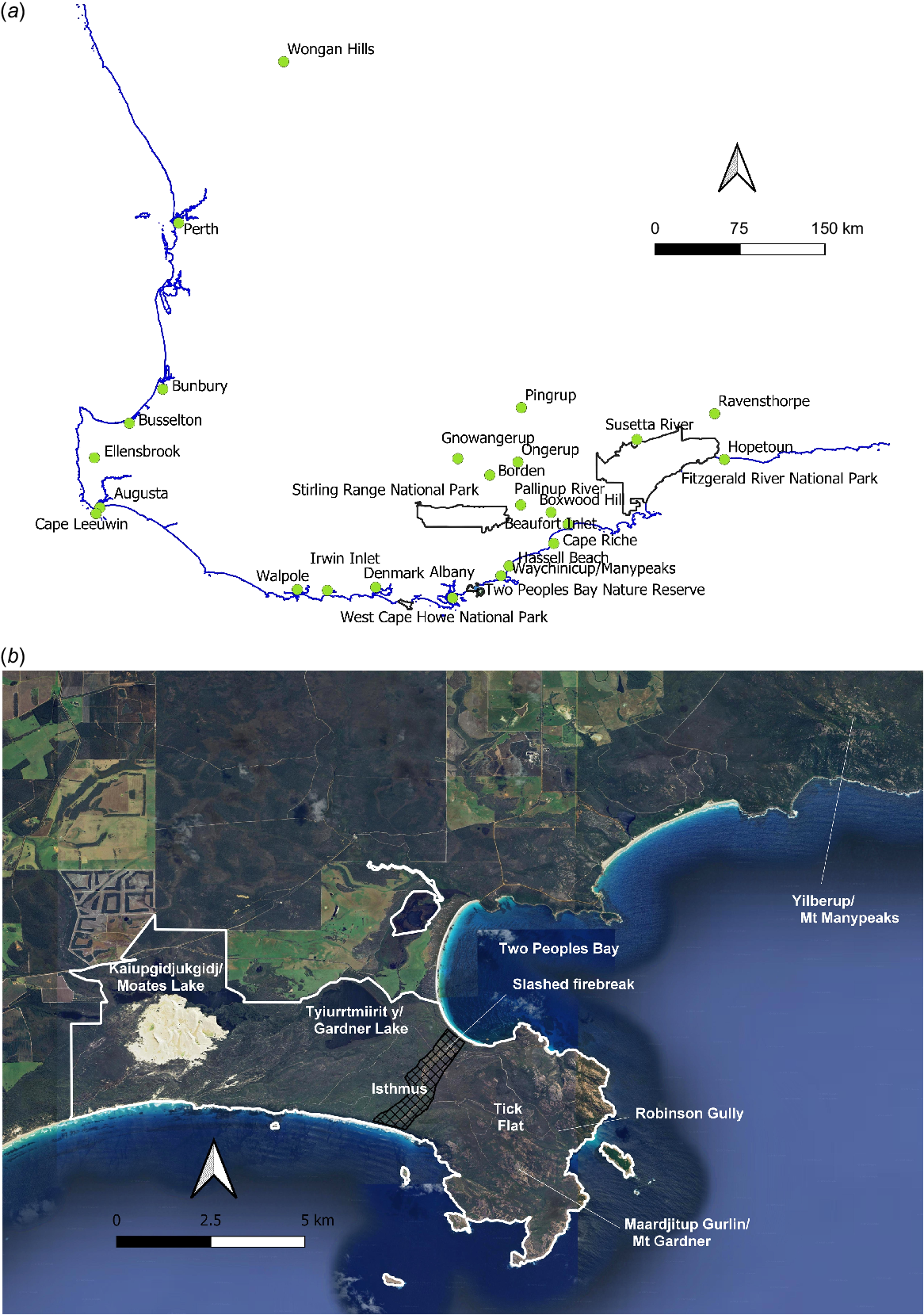

The only index of population size that can be obtained easily is the number of singing pairs. Booderitj/western bristlebirds, and Dading/western whipbirds have loud, complex, and distinctive species-specific calls (Smith and Robinson 1976; Smith 1987a, 1991). Locations of home ranges (= locations of singing pairs) of both species were plotted following methods of Smith and Forrester (1981). The locations of all singing birds were recorded during the five Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird surveys in 1976 and during other work on the Reserve. Where the data were ambiguous, data from 1975 to 1977 were used to help clarify the situation. If there was any doubt as to the number of pairs in a given area, the smaller number was chosen. In 1982, the locations of all Dading/western whipbird home ranges were again plotted by Smith and staff during three censuses for Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds, plus a small number of visits to other areas. Similar approaches were taken in subsequent years by A. Danks, S. Comer, A. H. Burbidge, or other personnel familiar with calls of Booderitj/western bristlebirds and Dading/western whipbirds. There are problems in obtaining this type of data because song bouts can be short and infrequent. These two factors make it difficult to locate birds accurately and neighbouring pairs are not often heard singing at the same time. The latter point is important because of the overlap in home range boundaries. Without data from the simultaneous singing of neighbouring pairs, the number of pairs may be over-estimated and the low song frequency will lead to under-estimates of the numbers of pairs in areas that are visited infrequently. As noted above, there have also been changes in personnel over time, but we have been careful to only involve observers familiar with calls of not only Booderitj/western bristlebirds and Dading/western whipbirds, but also Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds. In this paper, we focus on years where effort in locating home ranges was high and spatial coverage, at least for the area east of the isthmus (Fig. 2b), was also high.

(a) Map of south-western Australia showing place names and localities relating to the historical distribution of Booderitj/western bristlebird and Dading/western whipbird. (b) Map of Two Peoples Bay area showing the boundary of the nature reserve (white) and place names mentioned in the text, giving Merningar place names and spellings where known (from Knapp et al. 2024).

To illustrate the extent of an extensive fire at Two Peoples Bay in 2015 and show the extent of vegetation regrowth during the following year, we utilised remotely sensed Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) data available through the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/austmaps/about-ndvi-maps.shtml).

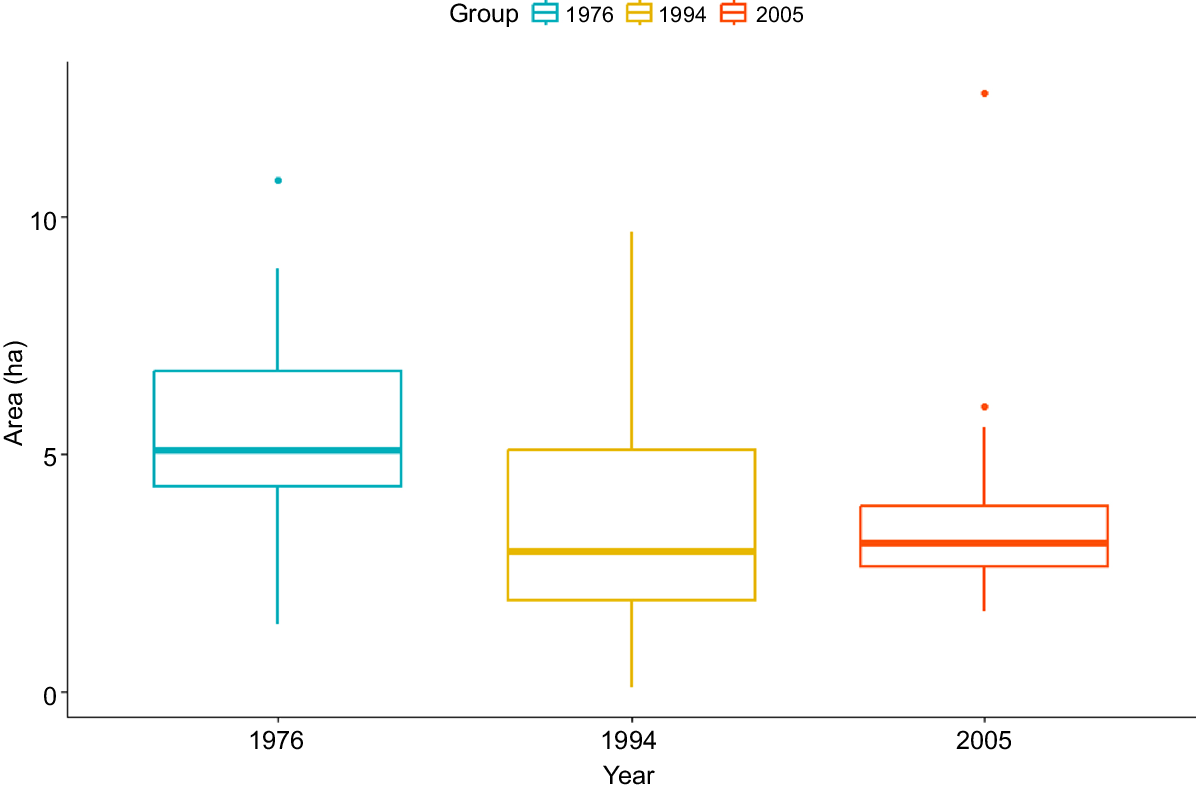

Song is the easiest method that can be used to obtain data on the size of home ranges. However, because song bouts can be short and infrequent, large numbers of observations are needed to build up an adequate picture of the home ranges. Home range estimates for Booderitj/western bristlebirds are available from three studies at Tick Flat (Fig. 2b) in Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. Smith (1987a; G. T. Smith, unpubl. data) plotted home range boundaries in this area in the 1970s and again in 1994 (Burbidge 2003). Using similar techniques, E. Fox (unpubl. data) plotted home range boundaries in the same area in 2005. Smith’s home range boundaries were not all well resolved. However, following Roberts et al. (2020), who provided a detailed discussion of contemporaneous mapping of Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds in the same area, we assumed that we minimised error by only using boundary points to estimate a 100% minimum convex polygon (MCP). Sizes of home ranges were compared using a one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey HSD test, using R ver. 4.0.2 (R Core Team 2024).

Another method for estimating home range size is to use radio-tracking, although it is logistically far more demanding. In a pilot project (Murphy 1994), several Booderitj/western bristlebirds were captured in the Tick Flat area in early November 1994, and each fitted with a numbered leg band and a small radio-transmitter glued to the inter-scapular area, following Raim’s (1978) method. In the early 1970s Smith (1991), using standard mist nets for passerines, captured, and colour-banded 23 Dading/western whipbirds, including nine pairs.

We investigated responses by Booderitj/western bristlebirds to call playback in and near Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in August–September 1995; i.e. early in the breeding season as defined by Smith (1987a). Calls used for playback were recorded using either a Sony Walkman Professional or Marantz PMD671 using directional microphones in previous years or during this study. At sites where Booderitj/western bristlebirds were known to occur, six ‘A’ calls (see Results for descriptions of calls) were played five times at 1-min intervals. A total of 66 trials were conducted (18 using the bird’s own call, 20 using a neighbour’s call, and 28 using a call believed to be unknown to the subject bird). If the subject bird responded with calls, a record was made of whether ‘A’ calls, ‘B’ calls (Smith 1987a) or other calls were heard. Approach of the subject bird was judged by the source of calls coming closer to the observer or by a Booderitj/western bristlebird being seen close to the observer. Statistical significance of observed differences was assessed using chi-squared tests.

Results

Booderitj/western bristlebird

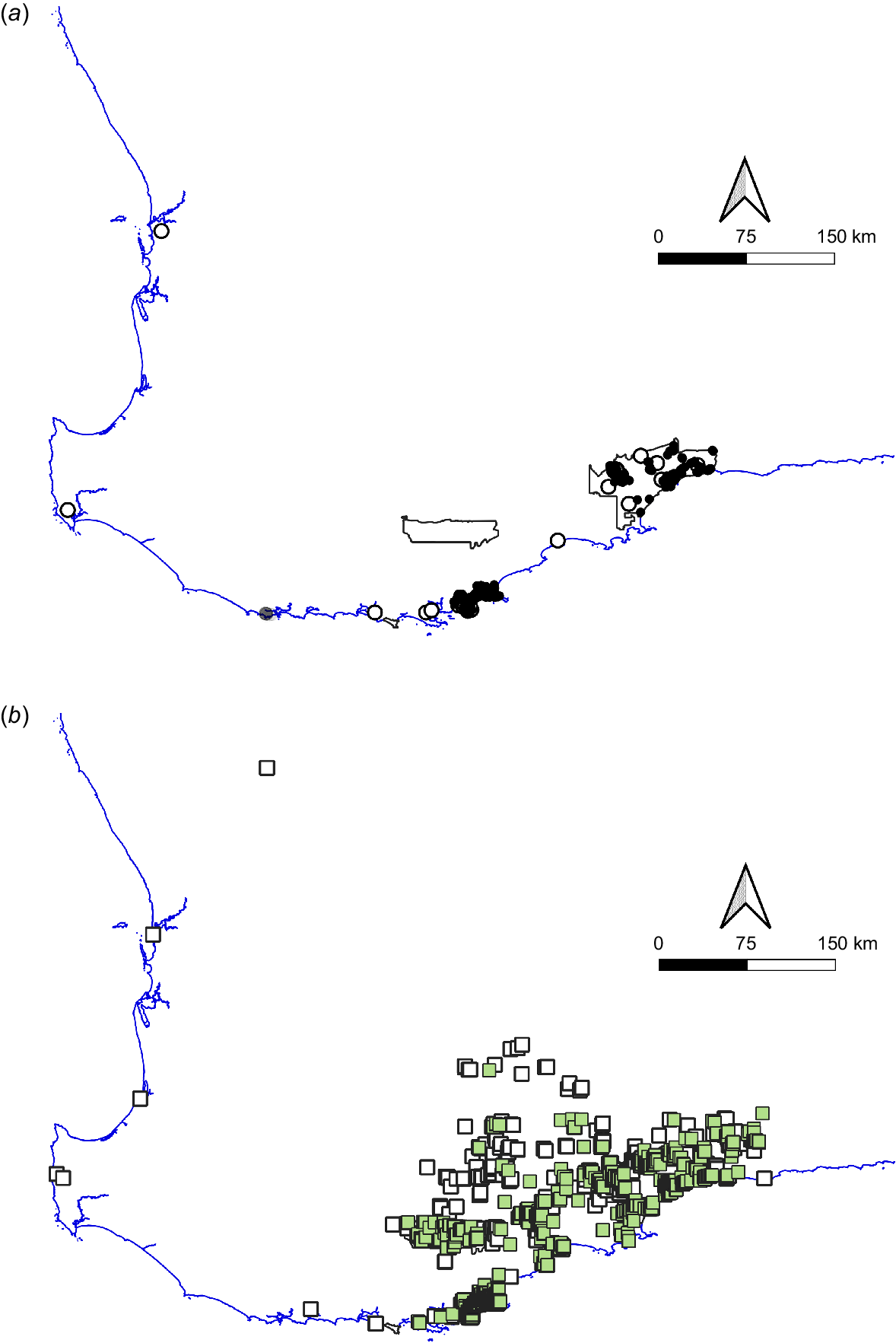

The Booderitj/western bristlebird was first recorded by western science near Perth by John Gilbert in 1839 (Whittell 1936; Fisher 1992) and later in the Albany district (Figs. 2a and 3a). He considered it to be generally distributed and implied that it had a similar distribution to that of the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird, but more restricted than that of the Dading/western whipbird (Slater 1973; E. Slater, pers. comm.). In 1866 and 1868–1869, George Masters collected 12 specimens in the Albany district and William Webb collected several specimens around Albany in the 1880s (Serventy and Whittell 1976). Whitlock discovered the species to the east of Denmark in 1907 (Whittell 1936). By 1924, Carter (1924) noted that ‘Bristlebirds were now rarely seen in areas where they were common 20 years ago’. Since then, it has been found at Two Peoples Bay (Buller 1945), Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks, Waychinicup River (Ford 1964), Fitzgerald River National Park (Smith and Moore 1977), and (probably) the upper reaches of the Sussetta River, just outside the northern edge of Fitzgerald River National Park (K. Newbey, pers. comm.). The species is also known from a sub-fossil deposit in Skull Cave, near Cape Leeuwin (Baird 1991).

Maps of south-western Australia showing historical and contemporary distribution of (a) Booderitj/western bristlebird and (b) Dading/western whipbird. Empty symbols are historical records; solid symbols are records from 2000 onwards; grey symbol represents a failed Booderitj/western bristlebird translocation. Reserve boundaries are shown for Stirling Range National Park and Fitzgerald River National Park.

A survey by McNee (1986) showed that Booderitj/western bristlebirds occurred between Two Peoples Bay and the southern end of Hassell Beach, north-east of Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks, and at three locations within or close to the Fitzgerald River National Park. The population found by Smith and Moore (1977) was apparently wiped out by a large fire in early 1985, but the area was recolonised by 1994 (McNee et al. 2021). Between these two main areas, McNee was unable to confirm the presence of the species at Beaufort Inlet. These locations are shown on Fig. 2a. It would appear that, in the 19th century, the Booderitj/western bristlebird was most common on the south coast between Denmark and Hopetoun with perhaps smaller and more isolated populations in coastal districts as far north as Perth. The current known distribution has been mapped by Burbidge (2007) and McNee et al. (2021).

Extinction of populations to the west of Two Peoples Bay can be explained by the frequent burning of the coastal heath in this area. This effect would have been exacerbated by the clearing of heath and the draining of swamps for agriculture, especially in the Albany district (Smith 1977, 1985a).

The Booderitj/western bristlebird is smaller than Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird or Dading western whipbird, being 180–200 mm in length and weighing about 30 g. Both sexes have the same brown plumage with grey speckling to the top of the head and mantle. With their sturdy build and relatively short and broad wings, they are superficially similar to the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird. Booderitj/western bristlebirds have prominent stiff rictal bristles, which Gould thought sufficiently significant to base the genus name on. The presence of bristles also differentiates these birds from scrub-birds that have none. Rictal bristles are tactile organs, but their precise function is not known (Delaunay et al. 2022). Nestlings are fairly uniformly dark grey-blackish (Danks 2025).

Booderitj/western bristlebirds are almost entirely terrestrial, moving quickly and agilely through the dense vegetation, often using tunnels made by quenda (Isoodon obesulus). While Booderitj/western bristlebirds appear to spend some time foraging in the dense heath, they rarely show more than a head above the vegetation. Their flight is feeble and appears to be used more as a mode of surprise escape than for locomotion, but they can move very quickly through vegetation without flying. Ten metres is the longest observed flight.

Booderitj/western bristlebirds are generally quiet, observing more than being observed. The main clue to their whereabouts is their song, which is given throughout the year, most frequently in the early morning and late afternoon and during the breeding season when song may be given throughout the day (Smith 1987a).

The most frequent song type is ‘A’ song, a highly variable melodious whistle of 5–8 notes. The second song type (‘B’ song) is a harsher whistle of three or four notes. Spectrograms of both call types ae shown in Smith (1987a). In 39% of 1487 song bouts, ‘A’ song alone was given, while in 59% of all song bouts the ‘A’ song was followed by the ‘B’ song in a duet. ‘B’ song was given alone in 1.5% of song bouts, in each case responding to the duet of a neighbouring pair (Smith 1987a). Only two birds have ever been recorded singing at the same time in a home range, and duets are assumed to originate from a male giving ‘A’ song and a female responding with ‘B’ song. However, individuals have been seen to give both song types in stressful situations. Without marked birds it is impossible to say whether one sex normally gives only one type of song, but it is likely that some songs are sex specific, as this occurs in the eastern bristlebird Dasyornis brachypterus, both in captivity and in the field (D. Bain, pers. comm.).

There is considerable variation in song type within and between individuals. Within a bout of ‘A’ songs, song type is consistent, but the next bout from the same individual is likely to be of a different song type. Individual birds may have more than 10 song types in their repertoire (A. H. Burbidge and D. J. Rogers, unpubl. data), similar to the rufous bristlebird (Dasyornis broadbenti) in south-eastern Australia (Rogers 2004).

The prime bristlebird habitat is dense closed heath (Fig. 4a–c), which provides cover from aerial and ground predators. The heath is relatively open at ground level and even in very densely-vegetated areas mammal tunnels allow the birds to move around while foraging. Many of the heath plants such as Anarthria scabra, Acacia spp., and Daviesia spp. provide an abundance of seeds, which presumably are easier to find on the ground under heath, with its thin or non-existent litter layer. While the abundance of terrestrial invertebrates in heath is low when compared with thicket and forest, there are small areas where they are more abundant, such as small Eucalypt patches and clumps of Anarthria scabra (G. T. Smith, unpubl. data). The Booderitj/western bristlebird uses open heath if there are sufficient patches of dense closed vegetation. Its use of open heath, thicket, and forest is uncommon and generally confined to small patches of these formations within an area of closed heath.

(a) Booderitj/western bristlebird habitat in the vicinity of Smith’s A-frame base camp used in his early work on Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds, Booderitj/western bristlebirds, and Dading/western whipbirds at Tick Flat, Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve (photograph: A. H. Burbidge). (b) Booderitj/western bristlebird habitat on slopes at lower Tick Flat in November 2022, showing regrowth of emergents 7 years after the 2015 fire. (Photograph: Alan Danks). (c) Booderitj/western bristlebird habitat on the slopes of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner (photograph: Sarah Comer). (d) Dading/western whipbird habitat on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner (Photograph: Sarah Comer).

Expansion of the distribution from the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland onto the isthmus (Fig. 2b) has been into areas of open heath, that have dense but small patches of Cyathochaeta clandestina and Dasypogon bromeliifolius, and dense regrowth coppices of Agonis flexuosa and Eucalyptus spp. in the swales of the old dunes. In this area, the heath is open because of heavy grazing by western grey kangaroos (Macropus fuliginosus) and due to slashing of vegetation for fire management purposes in the fire-break area of the isthmus.

Elsewhere, as on Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks where Booderitj/western bristlebirds were found along the ridge in the early 1980s following bushfire in 1979, once vegetation regrows to about 1 m after fire, it can become dominated by, e.g. Hakea cucullata or H. elliptica, and no longer suitable for Booderitj/western bristlebirds but may then contain Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird territories (Dilly et al. 2025; A. Danks and S. Comer, unpubl. data). At Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, Booderitj/western bristlebirds are not found in areas of dense Hakea but in the broad expanses of Anarthria sedgeland and low heath. These areas are contained within the mixed dense low heath vegetation communities described by Hopkins et al. (2024b), and can remain structurally suitable for Booderitj/western bristlebirds in the absence of fire for over 60 years. As at Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks, after fire, Booderitj/western bristlebirds can occupy some areas previously occupied by Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds. One such example occurred after the extensive 2015 fire when a long-term scrub-bird territory in tall dense shrubs in the lower part of Robinson Gully in Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve was completely burnt. By the following winter there was lush regrowth in this area, but only about 50 cm tall, and part of the former scrub-bird territory was occupied by a singing Booderitj/western bristlebird.

In 1976, the positions of singing birds were located on 609 occasions, including 63 occasions when two or more pairs were singing at the same time. These data together with a small number of observed movements indicated that in the 80 ha study area on Tick Flat there were eight home ranges, with a further four adjacent to them. Smaller numbers of observations in 1975 and 1974 (376 and 181) gave the same picture. The data from 1974 to 1976 were combined and are in Fig. 5.

Booderitj/western bristlebird home range boundaries in the Tick Flat area near Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner, Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, in 1976 (green dashed lines), 1994 (red lines), and 2005 (blue lines).

Limited data (50 observations) indicate that Booderitj/western bristlebirds also occupied these home ranges in 1972, 1973, 1977, and 1982. Data from another 12 home ranges suggest they too were occupied continuously from 1971 to 1982. In further surveys in 1994 and 2005, most home range boundaries were very similar to those in the 1970s (Fig. 5).

Home range size varied from 0.09 ha (home range number 12 in 1994) to 12.62 ha (home range number 23 in 2005) (Figs 6, 7).

Variation in area of Booderitj/western bristlebird home ranges in the Tick Flat area, Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in 1976, 1994, and 2005.

Variation in size of Booderitj/western bristlebird home ranges (100% MCP) for a set of common home ranges at Tick Flat, Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in 1976, 1994, and 2005.

One-way ANOVA using all available data for home range size estimates based on 100% MCPs gave F2,54 = 3.94, P = 0.025, suggesting that home range size has significantly changed across the three estimates. A Tukey multiple comparison of means showed a difference only between 1976 and 1994, with an adjusted P-value of 0.036 (Table 1).

| Group | Difference | Lower | Upper | P adj | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year_1994–Year_1976 | −1.9894970 | −3.874690 | −0.10430366 | 0.0363997 | |

| Year_2005–Year_1976 | −1.7601253 | −3.576743 | 0.05649248 | 0.0594260 | |

| Year_2005–Year_1994 | 0.2293717 | −1.587246 | 2.04598950 | 0.9502872 |

Within each home range the pair spent at least 60% of their time in one or two core areas of 1–3 ha (Smith 1987a). The daily pattern of movement varied from day to day, but the pair appear to be constantly on the move early morning and late afternoon at least. There are too few observations in the middle of the day to be sure of movements, if indeed they were active at that time. The pair spent most of their time together and of the 394 occasions when the distance between the birds was noted, 54% were together, 25% were less than 50 m apart, 16% were 50–100 m apart, and 5% were 100– 200 m apart. A limited number of reliable sightings (20 of 30) gave the same result.

Nevertheless, the social organisation of Booderitj/western bristlebirds remains poorly known. Two birds in the Tick Flat area in 1994 were each radio-tracked over an area of a minimum of 2.1–5.3 ha each day, but over a 5-day period utilised an area of at least 8.5 ha (Murphy 1994). At Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, pairs do not appear to defend their home ranges, and more than two Booderitj/western bristlebirds are sometimes associated with a given home range (Department of Parks and Wildlife 2014), but their social roles are not understood. During capture of 18 birds for a translocation, twice as many males as females were caught, although it is unclear whether this was because males are easier to capture, or there is a significant sex ratio bias (Burbidge et al. 2010).

Only three instances of presumed boundary disputes were recorded at the Reserve. On each occasion, all four birds were within 20 m of each other. The birds giving ‘A’ song sang continuously with only a few ‘B’ songs from the other birds. These interactions lasted from 2 to 5 min. Song appears to function as a method for the pair to maintain contact and for proclaiming occupancy of the home range. There is only limited reaction to birds singing in an overlap zone between home ranges. In the 1995 trials, there was no significant difference in response related to whether the playback was carried out from within the home range or from at or near the boundary (Table 2). Analysing each of the response parameters (calls, movements, sightings) separately also failed to show any significant differences with respect to position of playback.

| Boundary | Within | χ 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response | 19 | 24 | 0.06 | |

| No response | 9 | 13 | n.s. |

n = 65. n.s., not significant (P > 0.05).

The comparison between responses by subject birds to their own calls compared with neighbour’s calls are categorised in Table 3. In each case, the response was slightly greater following playback of the subject bird’s own calls (Table 3), but none of the differences were significant. Comparisons between responses to the subject bird’s own calls compared with responses to all other calls (Table 4) and known calls (own, neighbour’s) compared with unknown calls (Table 5) were more interesting. Again, the response was slightly greater following playback of the subject bird’s own calls, but these differences were not significant in the case of response measured by calling (Tables 4 and 5). However, the results were statistically significant for two parameters (whether the bird approached the observer, and whether the bird was seen) for the comparison of ‘own’ calls with all other calls (Table 4) and for sightings only for known calls versus unknown calls (Table 5).

| Calls | χ 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Own | Near neighbour’s | |||

| Heard to call | 14 | 13 | 0.26 | |

| Not heard | 4 | 7 | n.s. | |

| Approached | 12 | 7 | 2.64 | |

| Unknown | 6 | 13 | n.s. | |

| Seen | 9 | 4 | 2.57 | |

| Not seen | 9 | 16 | n.s. | |

n = 38, n.s., not significant (P > 0.05).

| Calls | χ 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Own | Other | |||

| Heard to call | 14 | 29 | 1.1 | |

| Not heard | 4 | 19 | n.s. | |

| Approached | 12 | 14 | 6.2 | |

| Unknown | 6 | 34 | * | |

| Seen | 9 | 6 | 8.5 | |

| Not seen | 9 | 42 | ** | |

n = 66. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; n.s., not significant (P > 0.05).

| Calls | χ 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Known | Unknown | |||

| Heard calling | 27 | 16 | 0.82 | |

| Not heard | 11 | 12 | n.s. | |

| Approached | 19 | 7 | 3.2 | |

| Unknown | 19 | 21 | n.s. | |

| Seen | 13 | 2 | 5.2 | |

| Not seen | 25 | 26 | * | |

n = 66. *P < 0.05; n.s., not significant (P > 0.05).

While information on the breeding of the Booderitj/western bristlebird is fragmentary (Smith 1987a), it suggests that August to September is the main egg laying period. However, in 1987, Lesley Harrison found an active nest in December (Danks 2025), which suggests that Booderitj/western bristlebirds may lay more than one clutch in a breeding season or at least attempt to replace losses.

The nest is globular (about 10 cm diameter) with a large side entrance. The base is made of the leaves of Dasypogon bromeliifolius, Lepidosperma sp., Cyathochaeta clandestina, and Anarthria scabra, with finer twigs and leaves of Loxocarya spp., Anarthria prolifera, and Restio spp. forming the bulk of the nest. The nest chamber is lined with fine Restio spp. and is about 5 cm in diameter. The nests are situated close to the ground usually in a dense shrub, D. bromeliifolius or A. prolifera.

Nothing is known of the role of the sexes in nest building, incubation, or feeding the chicks. Clutch size is probably two, as both Gilbert and Masters found nests with two eggs and Harrison’s 1987 nest also had two eggs (Danks 2025). Only one fledgling bird has ever been seen with the adults. It is not certain how long the young birds stay with their parents. Direct observations suggest at least a month after fledging. Southern heath monitors (Varanus rosenbergi) have been observed attempting to predate nestlings at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve (Danks 2025).

Booderitj/western bristlebirds are active feeders, whether on open ground or in dense heath. On the ground they are constantly on the move, pecking at the ground or occasionally digging into the sand with their bills. Their movements are quick and jerky, as the bird constantly turns from side to side by pivoting on its feet or moving the feet. Between feeding movements, they walk or hop slowly, interspersed with fast, short 50 cm dashes. Under jarrah Eucalyptus marginata clumps in the heath there is usually a layer of litter from 1 to 4 cm deep. The birds feed in these areas by probing under the leaves or by sweeping the leaves aside with a swinging action of the bill.

Buller (1945) reported that the stomach contents of one bird contained the remains of small Coleoptera, Hymenoptera, one small Tenebrionid larva, seven Acridiidae, and seven small seeds. One sample of faeces from Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve had both arthropod and plant remains, while the stomach contents from a road-kill had arthropod remains and seeds, including those of Anarthria scabra, Daviesia spp., and Acacia spp. The stomach of this bird was large with thick muscular walls, indicative of a seed-eating bird, in contrast to the thin-walled stomach of the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird. Booderitj/western bristlebirds have been seen feeding on Tenebrionid larvae, earthworms, and small unidentified insects.

The locations of 86 pairs in 1976 are in Fig. 8a. On Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland, there was an average of 7 ha of heath per pair, which is less than the 3–5 ha per home range found in the detailed study area (see above). This may mean that habitat is of lower quality beyond the detailed study area, or that the broader census resulted in an under-estimate. The maximum population in 1970 was calculated to be 60 pairs, by using the known distribution and assuming that the density was the same as in 1976.

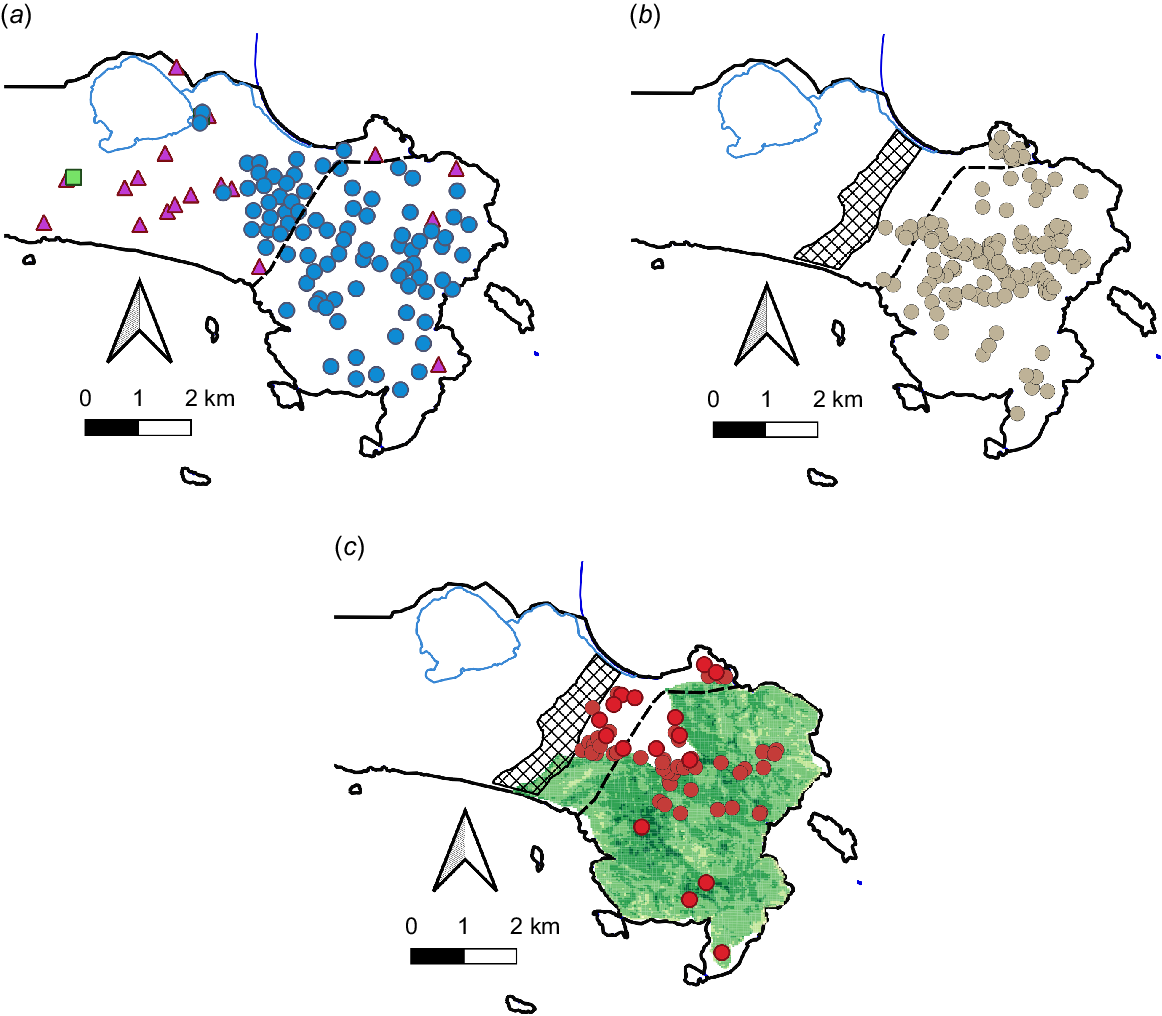

(a) Known location of Booderitj/western bristlebird pairs in Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in 1975 (squares), 1976 (circles), and recorded in 1982 but not in 1976 (triangles). The dashed line is the estimated limit of distribution in 1970. (Figure adapted from Smith 1987a). (b) Locations of Booderitj/western bristlebirds on the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland, Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, in winter–spring 2014 (i.e. before the 2015 fire). The hatched area shows the approximate extent of the slashed firebreak across the isthmus (Danks et al. 2024). (c) Locations of Booderitj/western bristlebirds on the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland, Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, in winter–spring 2016 (i.e. after the 2015 fire). Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) values from November 2016 are plotted for the area burnt in the 2015 fire.

In 1982, 40 of the 86 pairs located in 1976 were relocated on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland, together with an additional five pairs in areas where pairs had not previously been recorded. Given that the 20 home ranges that had been monitored over the previous 10 years were still occupied, it is probable that the number of pairs on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland may have increased by at least five. This would give a minimum population on the reserve at that time of about 100 (Fig. 8a).

In the mid-1980s, Booderitj/western bristlebirds were resident in the low-fuel buffer on the isthmus, with breeding activity recorded in this area. Since the low-fuel buffer maintenance (slashing) was commenced (Danks et al. 2024), the vegetation change resulted in the loss of Booderitj/western bristlebird home ranges in this area during the early 1990s.

By 2001, there were 158 ‘A’ calling Booderitj/western bristlebirds on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner (Comer and McNee 2004). However, in response to the 2015 fire, many birds appear to have moved off Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner and into the area east of the slashed break, where vegetation remained unburnt (Fig. 8c). Monitoring of threatened birds on the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland in the months immediately following the 2015 fire revealed the presence of a number of Booderitj/western bristlebirds within the burn area, which was unexpected given the extent and intensity of impact on the birds’ habitat. Some birds recolonised the burnt area, but mostly where vegetation growth had been strongest. At least one bird has moved into what was previously Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird habitat at the bottom of Robinson Gully where growth was rapid after the fire, due to high moisture levels in that area. By winter-spring 2016, less than 60 ‘A’ calling birds could be detected on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner and the nearby lowland (Fig. 8c). The most recent survey, in 2019 (Comer et al. 2020b), revealed the presence of 115 ‘A’ calling bristlebirds, almost twice the number recorded in 2016, but still somewhat less than the number encountered in 2001.

Historically, Booderitj/western bristlebirds occurred west of Albany (Fig. 3a), but there are no confirmed records in that area since the early 20th century. This means that Booderitj/western bristlebirds still in and near Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve remain the only population in higher rainfall areas of a once much more widespread distribution. A translocation, with the aim of increasing the number of sub-populations to decrease the risk of loss to bushfires, was therefore carried out using birds captured in the Reserve (Burbidge et al. 2010). In 1999 and 2000, 15 birds were translocated to a site near Walpole, about 130 km west of Albany, and another three to a nearby site in late 2007. All birds were screened for health parameters, and all proved healthy except that one had a very low number of eggs of a nematode, Capillaria. Although birds persisted for several years, the translocation was ultimately unsuccessful, possibly due to a combination of bushfire and introduced predators (feral cats Felis catus) (Burbidge et al. 2010).

Dading/western whipbird

The Dading/western whipbird was first discovered by John Gilbert in 1842, on a second trip to Western Australia, when the bird was recorded it at Wongan Hills, Perth, Busselton, Augusta, and Albany (Whittell 1951; Serventy and Whittell 1976) (Figs. 2a and 3b). George Masters collected eight specimens during a trip to Albany in 1868–1869, but there are no exact localities, and they may have been collected as far from Albany as the Pallinup River, which Masters visited (Whittell 1939; Serventy and Whittell 1976). In 1898, J. Harris collected the species at Bunbury (North 1904) and Milligan (1902) at Ellensbrook in 1901. Jackson recorded it near the Irwin Inlet in 1912 (Whittell 1952), Collins at Ongerup in 1929 (Howe and Ross 1933), and Watts at Gnowangerup in 1934 (Whittell 1939). Lindgren (1958) found the species 64 km west of Ravensthorpe, the Sedgwicks north of the Stirling Ranges (Sedgwick 1964), and Webster (1966) at Two Peoples Bay in 1962, while Ford (1971) found the bird at Mt Taylor in 1963 and 11 km east of Ravensthorpe in 1966.

Since these records, the Dading/western whipbird has also been recorded at Hopetoun, Fitzgerald River National Park, Beaufort Inlet, Cape Riche, Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks, Waychinicup Inlet, Boxwood Hill, Borden, and Pingrup (Department of Parks and Wildlife 2014). McNee (1986) documented records from published and unpublished sources and, during a survey in 1985, found Dading/western whipbirds in 38 of the 54 localities visited within the known distribution bounded roughly by Two Peoples Bay, Hopetoun, Ravensthorpe, and Pingrup. These localities are in Fig. 2. The species also occurs in a number of areas in South Australia (Burbidge et al. 2017) and north-western Victoria (Verdon et al. 2023).

In Western Australia, the Dading/western whipbird stronghold appears to have been mallee heath, with extensions to the west and south along the coast where structurally similar vegetation occurs. Like the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird, populations in the more developed areas have become extinct because of the changed fire environment, from patchy burning by Traditional Owners to more widespread and intense fires and agricultural clearing that followed European occupation of south-western Australia, especially in the 19th and early 20th centuries (Burbidge 2003; Department of Parks and Wildlife 2014; Dilly et al. 2025).

Dading/western whipbirds are slightly larger than Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds and Booderitj/western bristlebird, ranging in length from 240 mm to 255 mm and weighing about 50 g. Their general colouration is olive green, apart from the black throat with white sides. There is no sexual dimorphism.

Like the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird, they are stoutly built with long powerful legs, a long, graduated tail, and short, rounded wings. Although mainly terrestrial, Dading/western whipbirds spend a considerable amount of their time in the dense understorey vegetation where they may use their wings to elbow their way through the dense vegetation. They may also move to the top of the canopy to feed and occasionally sing. Their powers of flight are limited and are usually restricted to short, low flights above the heath or thicket. The longest flight observed was about 50 m. Generally, they are difficult to observe because most of their time is spent on the ground or in the dense understorey. However, on calm days during the breeding season, Dading/western whipbirds spend more time in the upper storey where they are easier to observe.

The most obvious sign of Dading/western whipbirds are their territorial songs. There are two variable song types whose mnemonics are ‘it’s for teachers pet’ and ‘quick more beer’ (spectrograms of calls from different populations of whipbirds are in fig. S1 of Burbidge et al. 2017). For convenience, these have been called ‘A’ song and ‘B’ song, respectively. ‘A’ song is the most frequent type and usually has more songs per bout. In 93% of all song bouts, ‘A’ song was the first, and in 50% of these bouts, there was a response with ‘B’ song. In the 7% of song bouts that started with ‘B’ song, only 10% were responded to with ‘A’ song. They have been seen to give both song types in stressful situations.

Observations of banded pairs (n = 7) suggest that each sex has its own song type, though under stressful conditions (e.g. after being handled) a bird may give both types of song. Although no birds have been sexed, behavioural observations suggest that the bird giving ‘A’ song is probably the male and that giving ‘B’ song is female. This conclusion is based on observations that the bird giving ‘A’ song is the dominant singer, spends less time incubating and feeding the young, feeds the other bird on the nest, and does not brood at night. While this conclusion is tentative, it will be used for convenience in the following sections.

Taxonomy of the Dading/western whipbird complex has been uncertain (Schodde and Mason 1991, 1999; Toon et al. 2013; Burbidge et al. 2017). It was long held that the group comprised a single species (Psophodes nigrogularis) but with varying numbers of subspecies (Schodde and Mason 1991). However, Schodde and Mason (1999), based on the limited available museum skins, proposed that there were two species: P. nigrogularis, previously widespread in south-western Australia, but now restricted to Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve and other nearby conservation reserves, and Psophodes leucogaster from north and east of Two Peoples Bay and southern South Australia and north-western Victoria (mallee whipbird). This arrangement conferred even greater importance to Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve and its vicinity, because it supported another endemic threatened species. To test this taxonomic hypothesis, museum specimens, supplemented with some new collections, were analysed genetically, with results inconsistent with Schodde and Mason’s (1999) conclusions based on morphometrics. Genetically, western and eastern populations are strongly divergent but geographically structured groups and there is no evidence for species level differentiation amongst western (or eastern) populations. Indeed, the evidence suggests that eastern and western birds represent two separate species, P. nigrogularis in the west and P. leucogaster in the east, each with two subspecies (Toon et al. 2013; Burbidge et al. 2017). One of these subspecies, P.n. nigrogularis, (Endangered) is endemic to the Two Peoples Bay area, including at Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks.

The prime habitat for Dading/western whipbird is thicket (Fig. 4), which appears to provide adequate cover for shelter but at the same time is open enough to not restrict the birds’ movements. Thicket holds the food resources required by the largely insectivorous Dading/western whipbird. Less frequently they may forage in forest, but their larger size and lower agility (c.f., Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird) would make them more vulnerable to predators in this habitat. All nests found to date have been in heath adjoined to thicket, as heath provides important protection for the bird and support for the cup-shaped nest. The new areas occupied on the isthmus have been thicket dominated by Banksia sessilis and coastal dune thicket.

The basic essentials of Dading/western whipbird habitat appear to be a short, two-layered association with the bottom layer being closed and the upper open to closed (Smith 1991). There appears to be no floristic factor, either directly or indirectly, in the form of litter type. Within the broad criteria of the habitat being short and two layered, the species seems flexible in its requirements. Habitat of this type can still be found from lower rainfall areas as far north as Pingrup, (annual rainfall ~350 mm) ca 100 km inland (Fig. 2a), to the humid coast (>800 mm).

While the primary habitat of the Dading/western whipbird is thicket, nests have been found in heath within 50 m of thicket. The species may also use areas of low forest adjacent to its thicket abode.

Data collated from five marked birds, during the period 1971–1976, suggest that home ranges are probably maintained for life, although home ranges of males and females are not necessarily exactly coincident (Smith 1991). Although survey effort is believed to have been greater in 1976 than in 1994, the mapped extent of home ranges (Fig. 9) suggests relatively high constancy of home range locations and boundaries over more than a decade. Both males and females remained in their home range after losing their mate, either from separation or by death.

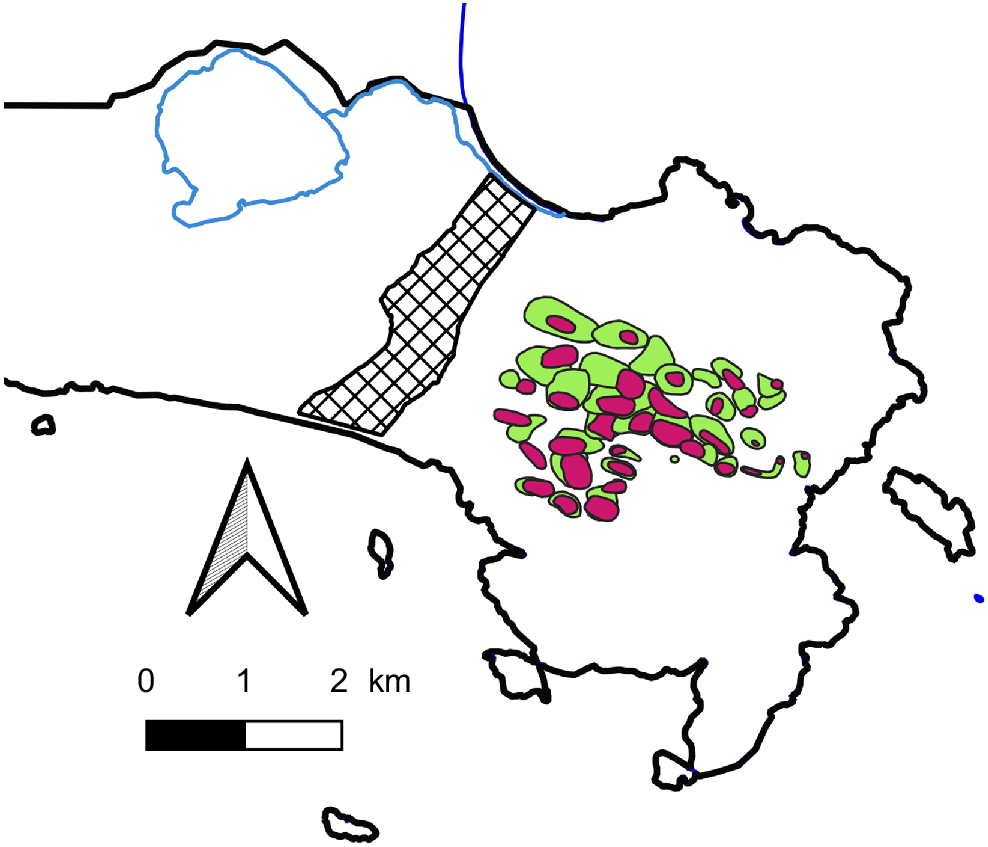

Dading/western whipbird home range boundaries in Smith’s (1991) main study area on the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in 1976 (green) and 1994 (red). Hatched area is the slashed firebreak.

The home ranges in the 1976 study area (Smith 1991) were about 13 ha, although the pairs spent most of their time in one or two core areas, which presumably had a better food resource. Pairs advertised their occupancy with song throughout the year. Most songs are given in the first hour after sunrise with a smaller burst before sunset and the frequency of singing is greatest during the breeding season.

The pairs usually stay close together during their daily activities, maintaining sporadic contact with their songs or if they are within sight, with soft contact calls. It is noticeable that if a pair is more than 50 m apart when a duet starts, then both birds move towards each other and the duet ends shortly after they make contact. This rarely happens when the birds are less than 50 m apart.

There is considerable overlap in home range boundaries (Fig. 9) and birds move freely through these overlap zones. Boundary disputes are rare and usually involve all four birds singing loudly at each other, but there appears to be little if any physical contact (Smith 1991).

Based on 15 nests, the breeding season extends from July to October, with egg-laying from late July to early September, the peak being in early August.

The cup-shaped nest takes 1–2 weeks to build, and eggs are laid up to 14 days after the nest is finished (Smith 1991; G. T. Smith, unpubl. data). If the nest site is disturbed while the nest is being built, the pair may desert and start another nest some distance away. Pairs tend to build their nests in the same area year after year. Nothing is known of which sex selects the nest site or does the building, although a few observations suggest that both birds help build the nest.

Incubation of the two eggs is shared, but the female sits twice as often as the male and for longer periods and always sits at night. The eggs may be left unattended for periods of 5–90 min. The longer periods usually occur when the female leaves the nest after sunrise to join the male for the first feed of the day. Occasionally, the male may feed the female after calling the female off the nest.

The eggs hatch after 21 days incubation and the chicks spend a further 10–14 days in the nest before fledging. Both parents feed the chicks, which are brooded after each feed for the first 3 days. After 7 days they are rarely brooded during the day but the female continues to brood them at night. Nest sanitation is maintained by the parents removing faecal sacs.

The parents appear to induce the chicks to fledge by decreasing the number of visits to the nests and by visiting the nest but not feeding the young. The chick’s tail and wings are not fully grown when leaving the nest and they are incapable of flight. They stay with their parents, usually one chick to a parent, until at least December and possibly until the start of the next breeding season. The parents continue to feed their young for at least 1 or 2 months after fledging.

Dading/western whipbirds are active feeders, constantly on the move, digging into the litter with their bill, searching through the dense rush and shrubs of the understorey, and probing into and pulling off the bark of trees. They also search the flowers of the Proteaceae family and may pull them to pieces in their search for insects and possibly seeds or nectar. In moving through the thick vegetation, they scramble and literally claw their way through, occasionally using their wings to elbow their way through particularly tight situations. When feeding on the bark of a tree, they may fan the tail and use it as a prop while they probe into and remove bark to search for insects.

Observations and examination of faeces suggest that Dading/western whipbirds are mainly insectivorous, taking a few seeds and small vertebrates. Of the prey items brought to nestlings, 45% were insect larvae, 25% were orthopterans, and the rest were made up of a wide variety of invertebrates, and one skink (Hemiergis peronii).

Away from Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, Rose (1991) reported two birds of P. nigrogularis oberon foraging by turning over leaf litter with their bill, and Elson (2008) observed birds of the same subspecies foraging on cockroaches and spiders and feeding a small skink (Hemiergis initialis) to nestlings.

The index of population size is the number of singing pairs. The locations of all pairs recorded in 1976 are in Fig. 10a. The 86 pairs were all confined to Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland. In 1970, the population was estimated to be a maximum of 60 pairs. This figure was estimated by using the known distribution in 1970 and assuming that within this area the density of home ranges was the same as in 1976.

(a) Locations of Dading/western whipbird home ranges at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in 1976 (adapted from Smith 1991). (b) Locations of Dading/western whipbird home ranges at Two Peoples Bay in 1982 (adapted from Smith 1991). Hatched area indicates the extent of the burnt (and later slashed) firebreak, but note that this was not fully in place in 1982 (Dilly et al. 2025), and the sites in the break where Dading/western whipbirds were recorded had not been burnt or slashed in recent years. (c) Locations of Dading/western whipbird home ranges at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in 2001 (data from Comer and McNee 2004). Hatched area indicates the extent of the burnt/slashed firebreak, and the grey shading indicates the extent of a large fire in December 2000. (d) Locations of Dading/western whipbird home ranges at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve in 2019 (i.e. post 2015 fire on Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner). Hatched area indicates the extent of the slashed firebreak. Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) values (from November 2016) indicate vegetation growth patterns within the area burnt in the 2015 fire.

Although the total number of occupied home ranges was smaller in 1982 (Fig. 10b), the data suggest that in the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner area the numbers of Dading/western whipbirds were probably the same and may have increased slightly. Since 1976, the birds expanded out of the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland and became common on the isthmus area, having moved west as far as Kaiupgidjukgidj/Moates Lake. In 1982 the population was probably of the order of 100 pairs.

By 2001 (Fig. 10c), Dading/western whipbirds had expanded into south-eastern parts of the headland and south-eastern parts of the isthmus, although overall numbers (85 calling males) appeared to be about the same as in 1982 (Comer and McNee 2004).

In the months following the 2015 fire, Dading/western whipbirds were rarely detected in the burnt area, but by 2019 (Fig. 10d) numbers were increasing, although there were still only about two-thirds the number of home ranges as mapped in 2001 (Comer et al. 2020b).

Discussion

Historical changes

Consideration of the possible evolutionary history of the Booderitj/western bristlebird and Dading/western whipbird, together with the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird, suggests that the distributions of all three were more extensive in the past. At the time of their discovery by Europeans they were reduced to the status of relict populations by the severe climatic oscillations of the Pleistocene. Their status in terms of distribution mirrors the length of their assumed evolutionary history. The Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird (with the longest history, having evolved in the late Eocene) was the most affected, being reduced to a small number of populations around the south coast. The Booderitj/western bristlebird’s origins are much younger (late Oligocene), and it has a larger distribution, whereas the Dading/western whipbird is thought to have evolved more recently, during the early Miocene (Oliveros et al. 2019), and had a comparatively large distribution in Western Australia and South Australia.

The advent of Europeans heralded a further decline in the distribution of all three species: (1) the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird to near extinction; (2) the Booderitj/western bristlebird confined to two areas on the south coast; and (3) the Dading/western whipbird to a number of isolated areas in the south-west. These changes are explicable in terms of the species’ habitat requirements and ecology.

Ecologically, the Booderitj/western bristlebird is close to the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird in that both species are physically cryptic and inhabit dense vegetation; at Two Peoples Bay their home ranges sometimes overlap (A. Danks, S. Comer, unpubl. data). However, Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird appears to have always had a patchy distribution centred on moisture retaining sites (Danks et al. 1996; Abbott 1999) while Booderitj/western bristlebird habitat is more extensive and the patches less isolated (Smith 1987a). In the past century, its distribution was probably mostly in wet closed heath, which is found only in coastal regions. By its very nature, heath readily carries fire (Keith et al. 2002; McColl-Gausden and Penman 2019). In south-western Australia, heath has been so frequently affected by fires caused by European settlers that the Booderitj/western bristlebird disappeared from much of the more developed areas of its pre-European distribution. Therefore, the Maardjitup/Mt Gardner to Yilberup/Manypeaks area is a key area for conservation management of this species.

Perhaps due of its relatively recent origins, the Dading/western whipbird is within broad limits, a habitat generalist. The widespread extent of suitable habitat and probably greater dispersive ability meant that the Dading/western whipbird was widespread and common at the time of European settlement. Subsequently, its habitat has been greatly reduced; however, sufficient has remained undisturbed in isolated pockets for the species to survive. Apart from the Two Peoples Bay/Mt Manypeaks area (Psophodes nigrogularis nigrogularis), most other whipbirds in Western Australia (P. nigrogularis oberon) occur in the Stirling Range and Fitzgerald River National Parks and the connecting Fitz-Stirling Macro Corridor (Wilkins et al. 2006; Bush Heritage Australia and S. Comer, unpubl. data), with only scattered, probably declining, remnant populations elsewhere (Burbidge et al. 2022). The Maardjitup/Mt Gardner to Yilberup/Manypeaks area is the only area where subspecies nigrogularis occurs, and is therefore of high priority for conservation management.

Two Peoples Bay

The most important area for Booderitj/western bristlebirds and Dading/western whipbirds at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve is the Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland, an OCBIL or old landscape (Hopper 2009, 2023), although the lowlands of the isthmus, YODFELs or young landscapes, are also important. In the period 1962–1970, a number of fires burnt large areas of the Reserve with the result that both species were confined to the headland. This suggests that the area has been and will continue to be an important refuge for these and other species. The value of the area as a refuge results from the topography and soils that have allowed the development of a mosaic of the habitats that suit both species (as well as the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird: Danks (1997)). In addition, the dissected topography and extensive outcrops of bare granite provide a natural network of firebreaks, which reduces the likelihood of the whole area being burnt at one time (Smith 1985b, 1987b; Danks et al. 2024; Hopkins et al. 2024b; Dilly et al. 2025). This results in favourable outcomes for both management of threatened species and conservation of Noongar cultural values (Knapp et al. 2024).

Habitat and response to fire

Qualitative examination of the data on habitat indicates that it is structure rather than the floristics of the vegetation that is the important determinant of whether an area is suitable for Booderitj/western bristlebirds or Dading/western whipbirds at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. In turn, the edaphic and microclimatic conditions at any site determine both the floristics and structure (Hopkins et al. 2024b), and hence the basic resources required by the species. The suitability of the vegetation of any site will also be modified by the fire history of the area. In general, the Dading/western whipbird appears more flexible than the Booderitj/western bristlebird in its use of vegetation, a factor that probably explains its wider distribution, which in turn may be a consequence of its more recent evolution (Schodde 1982).

The widespread occurrence of the root pathogen Phytophthora cinnamomi in the Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve (Hart et al. 2024) may have led to changes in the vegetation that are deleterious to Booderitj/western bristlebirds or Dading/western whipbirds. While there are some data indicating that total bird abundance is much lower in areas heavily impacted by Phytophthora, the main impact on avifauna is change in species composition, with nectarivores being significantly disadvantaged (Davis et al. 2014; Hart et al. 2024). To date, there are no data to suggest that P. cinnamomi has caused any adverse changes in the populations of Booderitj/western bristlebirds or Dading/western whipbirds in the Reserve, but it is possible that our monitoring to date has not been at a sufficiently fine scale to detect any such changes. Nevertheless, since Phytophthora may cause change in structure as well as floristics (Podger 1972), the situation needs to be closely monitored in future.

There were numerous fires in the period 1962–1970, mainly in the lowlands (Dilly et al. 2025), but the subsequent policy of fire exclusion led to an initial increase in the Booderitj/western bristlebird and Dading/western whipbird populations from about 1970. Dading/western whipbirds continued to occupy new locations up to 14 years after a fire, then only two further locations in the next 18 years; Booderitj/western bristlebirds followed a similar pattern, but few new locations were recorded for the first 20 years of monitoring (up to 1994) (Smith 1985a, 1985b; G. T. Smith, unpubl. data). However, the 2015 fire burnt most of the Booderitj/western bristlebird home ranges on the headland. Remarkably, some Booderitj/western bristlebirds were recorded on the headland within 2–3 months of the fire. The pattern of recolonisation since the fire has been linked to areas with more rapid vegetation growth, presumably related to soil moisture availability.

The distribution of Booderitj/western bristlebirds on the reserve has changed considerably since the creation of the Reserve (Fig. 8). Observations by HO Webster (G. T. Smith, pers. comm.) indicated that in the early 1960s the birds were found throughout the heathlands of Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner headland and the isthmus. However, by 1970, they were confined to the former area and although numbers did not start expanding again until 1973, Booderitj/western bristlebirds were approaching their 1960s distribution by 1982 (Fig. 8a). After that, they remained fairly constant until the 2015 fire.

Indeed, extensive fire such as the 2015 fire at Maardjitup Gurlin/Mt Gardner, and similar fires at Yilberup/Mt Manypeaks in 2004–2005 (Comer et al. 2005) and the Stirling Range in 2019 (Stokes et al. 2021), all had extensive impacts on populations of Booderitj/western bristlebirds, or Dading/western whipbirds, or both species. Early suppression of such fires (Driscoll et al. 2024) will be increasingly important in the future, for these and many other fire sensitive species.

Both Booderitj/western bristlebirds and Dading/western whipbirds have continued to inhabit >60-year-old vegetation on the headland. However, there is some evidence that, before the 2015 fire, Booderitj/western bristlebird home ranges were thinning out in the northwest of the headland area (in >60-year-old vegetation) but within the boundary of the 1970 distribution. Nevertheless, some birds were recorded in the burnt area months after the extensive 2015 fire, and more had moved into this area within 12 months fire. In some areas, habitat for Booderitj/western bristlebirds can become unusable if it gets too tall (e.g. in the flats north of the north-western end of the Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve) (A. Danks and S. Comer, unpubl. data). Habitat for Dading/western whipbirds at Two Peoples Bay does not appear to reach ‘senescence’ or unacceptable change except for the incidence of fire, although drought may initiate temporary loss of habitat quality. However, with the continuing warming and drying of the climate in south-western Australia, the incidence of serial heatwaves and droughts is likely to continue with severe implications for both habitat and individual birds (Ruthrof et al. 2016; Sharpe et al. 2019), which may mean that some areas currently occupied by Booderitj/western bristlebirds and Dading/western whipbirds may become unusable by them in the future. Focused survey of habitat usage will be important to inform future management of both these endangered taxa.

In the absence of fire, locations of home ranges can be constant through time, but the survey years where Booderitj/western bristlebird home range boundaries were plotted, 1976, 1994 and 2005, all had lower than average amounts of rain in the May–September period. Drought negatively impacts vegetation with the result that invertebrate food can become scarcer and harder to find, resulting in increased foraging costs for insectivorous birds, such as Booderitj/western bristlebirds (Fleming et al. 2021). This extra stress would likely have had an adverse effect on the frequency or intensity of calling (Pandit et al. 2022), which would probably have had the effect of reducing the observed size of home ranges in those years, as our home range estimates were based on observed patterns of calling. Extension of such survey work to include years with more varied rainfall patterns could provide important insights into the potential impacts of climate change and hence assist with better understanding of management requirements. Data on fire responses of Booderitj/western bristlebirds in the somewhat drier Fitzgerald River National Park indicate that very long (ca 40 years) fire intervals may be optimal in that area (McNee et al. 2021) and extension of that work may provide insights into what may happen in wetter rainfall areas as they become drier in coming decades. Similarly, further investigation of the response by Dading/western whipbirds to the December 2019 fires in the Stirling Range (Stokes et al. 2021) may provide insights of relevance to future management of the species at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve.

Extinction of populations of Booderitj/western bristlebirds and Dading/western whipbirds to the west of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve can be explained by the frequent burning of the coastal heath in this area. This effect would have been exacerbated by the clearing of heath and the draining of swamps for agriculture, especially in the Albany district (Smith 1977, 1985a).

Social behaviour

Although there is now good information on spatial occurrence patterns and response to fire, study of social interactions is difficult because both Booderitj/western bristlebird and Dading/western whipbird live in dense vegetation and are seen rarely.

Nevertheless, what is known suggests that social interactions, especially for Booderitj/western bristlebirds, may be much more complex than originally thought. For example, both species utilise home ranges that overlap with those of their neighbours. In addition, extra-pair birds have been found in Booderitj/western bristlebird home ranges. This (and other aspects of social behaviour) suggests that Booderitj/western bristlebird daily routine may be more complex than indicated from the mapping of song bouts. More research on activity patterns and social arrangements would be informative, especially if carried out at different times of year (e.g. breeding vs non-breeding seasons). Extra-pair birds have also been identified in eastern bristlebirds Dasyornis brachypterus and referred to as ‘floaters’ (Bain and French 2009). These birds could quickly replace birds holding home ranges when the opportunity arises or establish new home ranges when nearby vegetation becomes suitable. This makes it challenging to draw firm conclusions concerning post fire behaviour when birds are not marked individually.

There was no significant difference in response from playback on home range boundaries compared with playback from within the home range. However, this finding needs to be treated with caution, as boundaries were known well in the Tick Flat area, but not so well in most other areas. Nevertheless, it would seem that Booderitj/western bristlebirds are more likely to approach the source of a known (their own or a neighbour’s) than an unknown call. This is in contrast to many species of birds, which are equally or more likely to respond to a stranger, as has been known for a long time. For example, Harris and Lemon (1976), Baker et al. (1981), and Wunderle (1978) found that, following playback at or near the territory boundary, song sparrows (Melospiza melodia), white-crowned sparrows (Zonotrichia leucophrys), and yellowthroats (Geothlypis trichas) all discriminate between the songs of neighbours and strangers, and respond more strongly to the songs of strangers. This is usually explained in terms of neighbours being sedentary and expected to stay within their territories, whereas an unknown song clearly comes from an invader. It is energetically wasteful to pursue a neighbour once a territorial boundary is recognised. Booderitj/western bristlebirds may be different from strictly territorial species because they have overlapping home ranges and are frequently in the overlap region. The lack of reaction to birds singing in an overlap zone between home ranges, perhaps suggests that pairs hold their home ranges for a number of years and are well known to their neighbours. A similar conclusion can be drawn also for Dading/western whipbirds. The immediate management implication of the song response results reported here for Booderitj/western bristlebirds, is that attempts to capture Booderitj/western bristlebirds for conservation translocations are more likely to be successful if the call attractant (call playback) involves a call sequence known to the bird intended for capture.

Management implications

In terms of management, both Booderitj/western bristlebirds and Dading/western whipbirds may be placed in the category that Kitchener (1982) calls ‘p’ species; territorial with low powers of dispersal, low reproductive potential, and therefore vulnerable to disturbance. Alteration or destruction of habitat is the most potent hazard facing these species. Although the current descriptions of the habitats of Booderitj/western bristlebirds and Dading/western whipbirds are qualitative, they do provide a reasonable basis for assessing the extent of suitable habitat for each species, providing that the fire history for the area is known. If Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve is to continue to be managed for these species, then such assessments will be essential in planning for the future management of the area.

Since the creation of the Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve and the stationing of a permanent ranger there, the most serious hazard of fire has mostly been controlled. Absence of fire allowed considerable regeneration of the vegetation with a consequent expansion of the populations of both species. Fire can modify Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird habitat, making it suitable for Booderitj/western bristlebirds, albeit on a temporary basis. Management, through intentional burning or fire suppression, can therefore lead to habitat modifications that render a site more or less suitable for Booderitj/western bristlebirds and Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds; modification can reduce suitability for one and enhance it for the other. This means that a fire regime to suit Booderitj/western bristlebirds is different from the regime required for Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds, so there will be a trade-off in attempts to manage both species in the same area. While the 2015 fire had considerable impacts on Booderitj/western bristlebirds, Dading/western whipbirds, and Djimaalap/noisy scrub-birds (Dilly et al. 2025), if fire is kept out of the Reserve, all three species should continue to expand and occupy all available habitat, because they can all use habitat in the Reserve that is >60 years post-fire. This is demonstrated in part by the observation that home range locations (and, to some extent, home range size) have been relatively constant over decades.

One important consequence of fire suppression would be the increased likelihood of the birds becoming established in areas to the west of the Reserve (Smith 1987b). Nevertheless, the impacts of the 2015 fire, and the increasing risk of extensive fire resulting from the drying climate in south-western Australia, suggests that translocations should be considered as an increasingly important way of mitigating the level of such impacts. This would also involve detailed work on identifying potential translocation sites and careful management of fire and introduced predators and their impacts at the selected sites.

While the protective management technique has been appropriate for most of the time since the area became a reserve, it may not work forever. For example, before the 2015 fire, there was evidence that the areas of thicket were increasing at the expense of heath, favouring the Dading/western whipbird rather than the Booderitj/western bristlebird (Smith 1987b). In terms of their survival status, this direction of change is undesirable, and the situation needs to be monitored. This will require careful management of both planned and unplanned fires (Dilly et al. 2025), as well as monitoring the numbers and locations of both Dading/western whipbird and Booderitj/western bristlebird. However, in order to fully understand the impacts of management actions on population sizes, more research will be required in relation to social relationships, especially within Booderitj/western bristlebirds.

Based on conservation status, management objectives should be described in the order of priority: Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird, Booderitj/western bristlebird, and Dading/western whipbird, a prioritisation that is implicit in the South Coast Threatened Birds Recovery Plan (Department of Parks and Wildlife 2014). The Booderitj/western bristlebird, and Dading/western whipbird (along with the Djimaalap/noisy scrub-bird) each occur patchily across Two Peoples Bay Reserve, and each have slightly different requirements in relation to fire. However, in broad terms, absence of fire is beneficial for all of them, and the main increases in all three populations have resulted from the effect of the absence of fire on the availability of habitat for each species in the Reserve and the structural integrity of these types. Nevertheless, these are aspects that need careful monitoring in the future and the overall management strategy may well require some carefully planned burning of senescent vegetation. It is important that this is done in a collaborative way, involving both institutional managers and local Noongar people, leading to effective outcomes in terms of both conservation management and long-standing Noongar cultural values.

Data availability

The data that support this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest

Graeme Smith died in 1999. He had no known conflicts of interest, nor do the living authors of this paper.

Declaration of funding

This research would not have been possible without the invaluable assistance of salaries and operating budgets paid for by the Western Australian Government (Departments of Fisheries and Wildlife, Conservation and Land Management, Environment and Conservation, Parks and Wildlife, and Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions). Much of the early research was supported by CSIRO Division of Wildlife Research. Funding for some aspects of later work was provided through the Australian Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water and its predecessors, and BirdLife Australia.

Acknowledgements

We thank Denis Saunders for re-launching this collection of papers on Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve, and for editorial assistance and comments on penultimate drafts of the text. We are grateful to Dr David Bain and Michael Brooker who made constructive comments on a draft of this paper; together, their comments have made a valuable contribution. Author Graeme T. Smith was the contributor to the original version of this paper, which was written for a special bulletin of CALMScience on the natural history of Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve. The paper was subject to peer review, revised, and accepted for publication in 1991. The special bulletin was never published. By the time the papers collected for the special bulletin were once more collated in order to publish them over 30 years later in the special collection of Pacific Conservation Biology, author Graeme T. Smith was deceased. Accordingly, Allan Burbidge, Sarah Comer and Alan Danks updated the paper, added much material on work carried out since the original manuscript was drafted, contributed the photographs and maps, and edited the manuscript for final publication. G. T. Smith would have met criteria for authorship if alive, so is included as an author on this version. We are grateful to Graeme Smith’s daughters for their agreement and encouragement to proceed with preparing this paper to honour the memory of their late father. Graeme Smith was ‘grateful to Mike Ellis and Les Moore for their assistance and companionship in the field. Dick Grayson (deceased or uncontactable), (the late) Ron Sokolowski, (the late) Graeme Folley, and Alan Danks also provided assistance at Two Peoples Bay over the years. (The late) Norm Robinson and the late Harley Webster generously shared their knowledge of the rare birds and Norm provided much appreciated help and advice at the start of the project. (The late) Ian Rowley kindly read and commented on the earlier drafts of the manuscript, and Allan Burbidge, Andrew Burbidge and Mike Brooker made valuable criticisms of the text.’ We are grateful for the dedication and support of members of the Western Bristlebird Recovery Team 1994–1996 and the South Coast Threatened Birds Recovery Team 1996-present (for both Booderitj/western bristlebirds and Dading/western whipbirds). The Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme provided project permits and leg bands. Lesley Harrison, Shapelle McNee, Ted Middleton, and many other volunteers have assisted with censusing and monitoring. Research on Booderitj/western bristlebirds and/or Dading/western whipbirds at Two Peoples Bay was carried out under permits and approvals from the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions and its predecessors, including SPP 1993/0065, Animal Ethics Committee approvals CAEC/13/1994, CAEC/13/2000, CAEC/14/2001, DEC AEC 15/2007, and Fauna Licences SC000389, SC000843, SC001234, SC001311, SC001394 (AHB) and SC000763 (SC).

References

Abbott I (1999) The avifauna of the forests of south-west Western Australia: changes in species composition, distribution, and abundance following anthropogenic disturbance. CALMScience Supplement 5, 1-175.

| Google Scholar |

Abbott I (2009) Aboriginal names of bird species in south-west Western Australia, with suggestions for their adoption into common usage. Conservation Science Western Australia 7(2), 213-278.

| Google Scholar |