Increasing Pacific Islander research and authorship in the academic literature

Sangeeta Mangubhai A * , Ron Vave

A * , Ron Vave  B , Shereen Shabina Begg

B , Shereen Shabina Begg  C , Mereoni Chung A , Semaema Vakaciriwaqa Dileqa

C , Mereoni Chung A , Semaema Vakaciriwaqa Dileqa  D , Yimnang Golbuu

D , Yimnang Golbuu  E , Chelcia Gomese

E , Chelcia Gomese  F , Romitesh Kant

F , Romitesh Kant  G , Salanieta Kitolelei

G , Salanieta Kitolelei  C H , Ravinesh Ram I , Nunia Thomas D , Rufino Varea J and Andra Whiteside K

C H , Ravinesh Ram I , Nunia Thomas D , Rufino Varea J and Andra Whiteside K

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

Abstract

Disseminating research through academic publishing is essential for contributing to global knowledge, advancing critical fields and finding solutions to humanity’s challenges. However, for Pacific Islanders, navigating the path to publication can feel like crossing a vast ocean while weighed down by systemic barriers that make sharing knowledge, lived experiences and unique worldviews with the broader academic community difficult. Using an Indigenous talk story methodology (talanoa), discussions were held with early- and mid-career Pacific Island researchers to identify the main barriers collectively faced. These barriers included insufficient time and funding, poor recognition of Indigenous research methodologies, inequitable partnerships with researchers from the Global North, lack of local academic mentors, linguistic hurdles and biases in the academic system. We outline strategies aimed at dismantling systemic barriers faced by Pacific researchers when designing and conducting research, writing manuscripts and publishing in the academic literature. Our discussion highlights pathways for greater inclusion of Pacific scholars in academic publishing to which Global North researchers, academic journals and funding agencies can contribute. Removing barriers is essential to leverage the unique insights of Pacific Island researchers, whose contributions are vital for developing locally-driven, globally impactful solutions to the biodiversity and climate change crises.

Keywords: academia, barrier, discrimination, diversity, equity, Global South, knowledge systems, Pacific countries, researcher.

Introduction

Addressing the global biodiversity and climate crises requires diversity of perspectives and knowledge systems (Asase et al. 2022; Aini et al. 2023). Publishing in the academic literature is an important pathway for disseminating new knowledge, ideas and innovations, allowing researchers to contribute to the global understanding of critical topics, advancing fields and influencing policy. In the highly competitive world of academia, scholarly output determines an individual’s professional success (Maas et al. 2021). The phrase ‘publish or perish’ reflects the pressure on academics to publish in high impact journals to gain and maintain scientific credibility, funding and university tenure, and advance careers (Davies et al. 2021). Researchers working outside academia (e.g. research institutions, non-government organisations) may publish work in academic journals to maintain credibility as scientists, demonstrate expertise on specific subject matter and access research grants.

However, the ability or opportunities to publish are not the same for everyone. There is an increasing body of work on systemic inequities within academia, highlighting barriers marginalised groups face publishing, particularly women, people of colour, persons with disabilities, those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer, asexual and other sexually or gender diverse (LGBTQI+), non-native English speakers and other underrepresented groups (Chaudhury and Colla 2021; Davies et al. 2021). Gender and racial bias in peer review processes, the underrepresentation of minority voices in research and the lack of diversity in editorial boards are considered to contribute to these disparities (Brodie et al. 2021). There are growing calls for reforms in academic publishing to foster greater equity, inclusion and diversity in scholarly discourse (e.g. Davies et al. 2021; Maas et al. 2021). However, this will not happen without understanding and dismantling the underlying systems maintained by those in positions of power and privilege that consciously or unconsciously promote inequities and discrimination.

Methods

Pacific Islanders face a unique set of complex and multifaceted barriers when attempting to publish research in academic journals. This is reflected for example, in the low number of papers published in Pacific Conservation Biology that were led by authors based in the Pacific (5) compared to Australia (49) in 2024. To explore this further, the lead author held a 1–1.5 h talanoa session with each co-author on how to improve the representation of Pacific Islands research and authorship in the academic literature. Talanoa is an Indigenous Fijian research methodology rooted in storytelling, dialogue and relationship-building. This involves open, respectful and genuine conversations where participants share experiences and ideas in a personally meaningful way (Nabobo-Baba 2006). Talanoa sessions were recorded with the permission of the co-authors.

In writing our paper, we acknowledge our positionality as researchers committed to centring Pacific voices and being authentically rooted in Pacific contexts. Although Hawai’i, Australia and New Zealand are considered Global North nations, we acknowledge Indigenous researchers from these countries may face academic obstacles that are best articulated and addressed through their own narratives. Our approach aligns with our broader goal of decolonising research methodologies by amplifying the voices of those directly impacted by the issues we explore (Tualaulelei and McFall-McCaffery 2019).

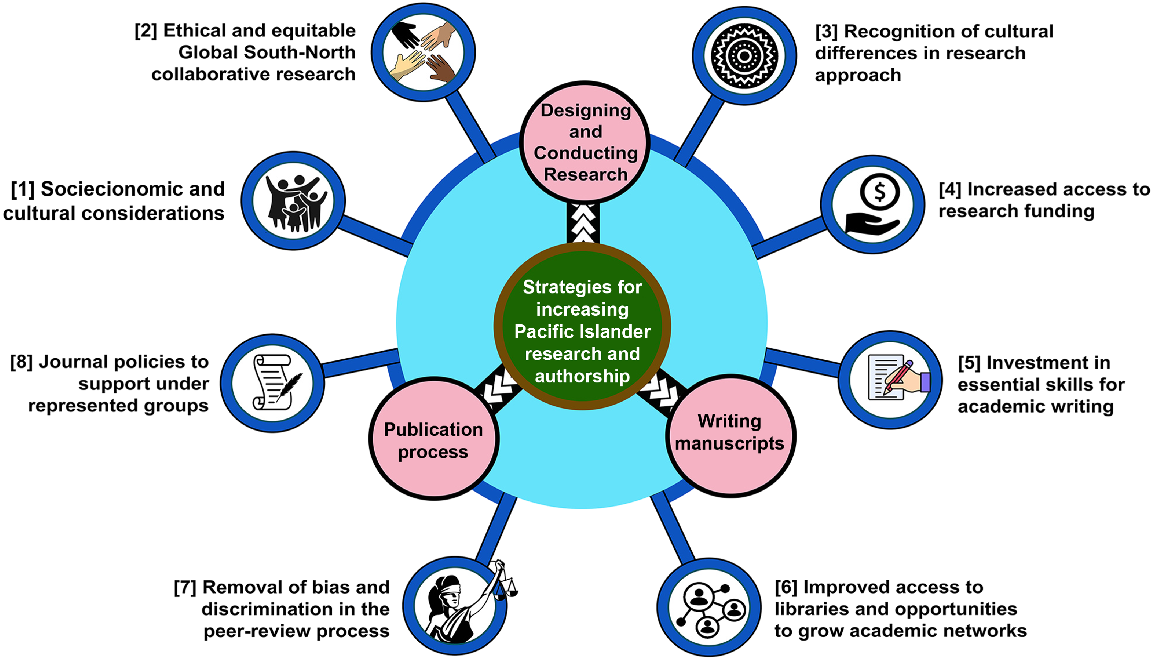

Our perspective piece reflects the collective viewpoints of five early- and eight mid-career researchers from Fiji, Palau and Solomon Islands with Doctor of Philosophy and Masters degrees in the fields of conservation, fisheries, gender or climate change. We highlight eight key strategies to address the systemic barriers Pacific Islander researchers (hereafter ‘Pacific researchers’) face, with a focus on practical solutions. Grouping strategies into three main topics ‒ designing and conducting research, writing manuscripts, and publication process (Fig. 1) ‒ our perspective piece focuses on pathways for systemic change and targets specific audiences including researchers from the Global North, academic journals and funding agencies.

Designing and conducting research

Socioeconomic and cultural considerations

I’m one of the few in my family who did tertiary studies and completed a Masters. It meant that once I completed my degree, I had a responsibility to earn money immediately. I did not feel I could stay on at the university to write up my work [unpaid] and submit it to a journal. (Mereoni Chung, mid-career)

Sometimes there is this expectation that we do research for free. However, that is hard because our livelihoods are often critical to our family, which in the Pacific includes the extended family. We have cultural obligations too. So doing research for free in my spare time is not an option for me. (Nunia Thomas, mid-career)

Time to lead and write up research is a major barrier for many Pacific researchers. Similar to others in the Global South (Asase et al. 2022), local researchers may have low salaries necessitating taking on consultancies, additional teaching at universities or non-academic jobs to supplement income, leaving little time to publish research. This may be compounded by a myriad of commitments to immediate and extended families, the wider community, religious institutions and specific cultural obligations that extend into weekends and holidays. Others volunteer time to support local organisations with fundraising or serve on boards (e.g. Fidali et al. 2023), and are frequently engaged in community education, advocacy and development to a greater extent than counterparts in the Global North (Asase et al. 2022). These activities often involve significant personal expense, going beyond the simple donation of time.

The time and financial resources needed for research is often higher because the socio-cultural context of the Pacific Island region demands a more integrated approach to science that blends traditional knowledge with modern research methodologies (Kitolelei et al. 2021; Harangody et al. 2022; Aini et al. 2023; Jekope Ramala and Ruwhiu 2024). This requires efforts to build genuine trust with local communities, ensure cultural protocols are respected and incorporate Indigenous perspectives. This also necessitates more extensive consultation, participatory research design and culturally appropriate dissemination of findings, all of which extend the research timeline and budget. Consequently, researchers working in the Pacific Island region often face logistical and ethical complexities not typically encountered in other research environments.

Addressing these barriers necessitates a multi-pronged approach that acknowledges both the systemic and cultural realities of the Pacific Island region, and an understanding that having time is strongly linked to having flexible and adequate funding. Funding models are needed that are flexible and comprehensively encompass the entire research lifecycle – from data collection and community engagement to final publication and the sharing of results with communities. Critically, funders must eliminate the dichotomous choice between community engagement and academic publication, a situation in which Pacific researchers, driven by cultural ethos, will invariably prioritise the former. Funding must cover realistic research costs including adequate salary support, thereby mitigating the necessity for researchers to contribute unpaid labour or pursue multiple income sources that ultimately detract from research productivity and quality. Support for short-term writing sabbaticals at overseas universities may overcome the challenge of finding limited time to write outside of work hours and in home settings, due to socioeconomic and cultural obligations.

Ethical and equitable Global South-North collaborative research

There is a kind of underlying threat to your career ‒ that if you do not follow their rules and their systems, there will be implications for your career. (Ron Vave, mid-career)

We are constantly having to justify the work we did and argue for authorship for ourselves and our Pacific colleagues. It makes us feel undervalued. When it happens over and over again, we start to question the motivations of outsiders coming to do research in our countries. (Sangeeta Mangubhai, mid-career)

Pacific researchers working both within or outside academia often struggle to find lasting research partnerships to sustain research pursuits and had mixed experiences regarding collaborations with researchers from the Global North. Positive relationships were fostered where the research was collaborative and inclusive from beginning to end, where local inputs were respected and valued, and ultimately helped Pacific Islanders become better (and more independent) researchers. Three of the authors have established long-term relationships through which students, joint grants and publications have been obtained. However, most authors (early- and mid-career) described toxic relationships with researchers from the Global North that reinforced notions of ‘white supremacy’ and resulted in feelings of being undervalued and exploited. This included foreign researchers using local researchers to obtain permits or access relationships with government, provincial offices and local communities, or treating the local researchers as research labour (e.g. translators, data collectors) rather than intellectual contributors. Many raised concerns about the rise of ‘parachute science’, in which researchers from wealthier countries design and execute studies with minimal involvement from local researchers, often prioritising quick publications over ethical and locally-informed research practices (de Vos et al. 2023). In many cases, the inclusion of local researchers was an afterthought and tokenistic, with an expectation that these local researchers should be grateful for being included in field work and acknowledged in academic papers. These negative experiences are entrenching a mistrust of outside researchers that can compromise future research in the Pacific Islands region.

Multiple approaches are needed to address parachute science and several papers have provided practical guidance on how to create healthy, equitable and ethical relationships between Global South and North researchers (e.g. Chin et al. 2019; Stefanoudis et al. 2021; de Vos et al. 2023). We suggest that universities and research institutions in the Global North establish exchange programs and collaborative research projects with Pacific Island universities and independent researchers. These programs could involve hosting Pacific researchers at international institutions for short-term research stays, providing access to experts, resources (including advanced research facilities) and mentorship that may not be available in home countries.

Collaborative projects are recommended to be designed to ensure that Pacific researchers and/or Indigenous community elders take on leading or key roles and be part of all aspects of the research such as design, analysis and writing (Vave et al. 2024), rather than simply being seen as junior partners. Ideally, these collaborations should be multi-year partnerships to ensure that capacity is strengthened and research moves from baseline information to more complex research questions (Asase et al. 2022; Aini et al. 2023). Pacific researchers should be included as authors on research in local regions led by Western scientists to ensure that local knowledge, perspectives and expertise are adequately and accurately represented in the research process and outcomes. Pacific Islanders’ deeper understanding of the local environment, culture and challenges can provide critical context and new insights that enhance the quality and relevance of the research and are therefore more likely to have a positive impact locally (Aini et al. 2023). Including local scholars as co-authors and providing opportunities to lead papers helps to address the historic injustices where research conducted in the Pacific often excluded or minimised the contributions of local researchers. This may require adopting more inclusive criteria than the narrow set that academic institutions or journals use to determine authorship on manuscripts. Authorship not only acknowledges the intellectual contributions but also supports the professional development of Pacific researchers and associated recognition in the global scientific community.

Recognition of cultural differences in research approach

When we write about the Pacific we are expected to analyse and craft our lived experiences to theories and frameworks that have been developed in the Global North, by Global North researchers, even if it does not fit. Maybe what we should be doing is just telling our stories as is, sharing our theories and concepts, rather than diminishing our work by fitting into frameworks that do not make sense for the Pacific. (Romitesh Kant, early-career)

Pacific Islanders conduct socioeconomic research that is embedded in local contexts and cultures, employing epistemologies that may not align with Western scientific paradigms. For example, Pacific-led research may prioritise relational or communal knowledge systems that can be misunderstood or undervalued by reviewers unfamiliar with these perspectives. The traditional practice of providing a gift as a gesture of appreciation (e.g. blebel or osngelelin in Palau, vakavinavinaka in Fiji, ho‘okupu in Hawai’i) when doing fieldwork in communities is often misinterpreted as paying for information by outsiders. For some, theorising Pacific systems and experiences within Western frameworks has been challenging and there has been resistance to Pacific-centric frameworks (S. Kitolelei, R. Vave and R. Kant, pers. comm.). Furthermore, Indigenous knowledge systems, participatory research methods and oral traditions (Nabobo-Baba 2006; Jekope Ramala and Ruwhiu 2024) are often marginalised in favour of quantitative approaches.

These examples of differences in approach can become obstacles to framing research questions and methods, and requires greater recognition of Indigenous and local knowledge systems and non-Western methodologies. This can be achieved by encouraging journals to adopt more inclusive editorial policies that value diverse epistemologies. Editorial boards should include editors who are knowledgeable about Indigenous knowledge systems and methodologies, ensuring that research from Pacific researchers is reviewed by those who understand the cultural context in which research is conducted. Through demonstrating the relevance and rigour of Pacific Island research and the contribution of these to addressing global challenges such as conservation, climate change and sustainable development, journals may be more inclined to publish works that employ Indigenous methodologies or Pacific-centric approaches.

Increased access to research funding

Access to diverse, sufficient funding is a challenge for Pacific Islanders. Not only do we need to get funding to do the work and publish, but also for returning and sharing our findings with the communities we work with, in their preferred languages. (Ravinesh Ram, mid-career)

Access to sufficient, consistent research funding was a significant barrier repeatedly experienced by all authors. Pacific Island countries have small economies and therefore there are fewer grants and funding opportunities (including at universities) specifically dedicated to students and researchers from the region. Local researchers often struggle throughout their career to secure the financial support necessary for conducting studies of global significance (a requirement for academic publication), accessing advanced (often expensive) equipment and covering publication fees. For example, a natural sciences doctoral candidate at the University of the South Pacific receives US$5000 to undertake research, limiting the data that can be collected and the scope of the study. International funding bodies may not prioritise research in the Pacific region; but if prioritised, there may be requirements for funding to go through or partner with an institution based in the Global North that may dictate and consume a disproportionate amount of the budget in salaries and overheads. International funding opportunities may not always be accessible to Pacific Islanders due to lack of awareness of grants or overly complex, highly-Westernised application processes (Fidali et al. 2023).

Multiple approaches are needed to increase Pacific researchers’ access to direct research funding. National governments, international and regional organisations, donor agencies and academic institutions should allocate more resources specifically targeted at the Pacific Island region. This could include establishing dedicated funding schemes or fellowships that provide grants for research projects, travel to conferences and publication fees. Financial support could be structured to cover the costs of data collection, fieldwork, and access to laboratories and other research infrastructure. Significant funding going to regional agencies in the Pacific (e.g. Pacific Community, Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme) could have allocations for Pacific researchers. For example, the Pacific European Union Marine Partnerships Programme set aside US$698,000 (1.5% of US$46.3 million funding), and supported four Masters and four PhD students with full scholarships at the University of the South Pacific. Full scholarships (including a salary) could be provided to enable Pacific researchers to visit and write up research in outside universities. Collaborative funding models (i.e. where Pacific researchers partner with colleagues from more developed nations to access grants) could set criteria or guidance to intentionally address bias, discrimination, and skewed power relations and dynamics. This could include grants requiring: (a) adoption of approaches that intentionally address systemic and historical biases; (b) equal number of principal investigators from the Global North vs South; and (c) closer scrutiny of who benefits from the research and how (e.g. funding allocation, authorship on papers, etc.).

Writing manuscripts

Investment in essential skills for academic writing

I had the opportunity to attend workshops and training on publishing which helped me -– but I wish the same would have been for my colleagues as well. (Chelcia Gomese, mid-career)

People sometimes look down on us for the way we write in the Pacific. This can have an effect on our psyche ‒ it can erode our confidence. It makes us question ourselves. We have to keep reminding ourselves that we can make it as scientists, that we have value in our countries, value regionally and globally. (Salanieta Kitolelei, mid-career)

After conducting research, Pacific researchers face further hurdles in drafting manuscripts. The preferential use of English in science and by journals creates a language barrier for non-native English speakers to publish research, obtain credit via publishing, and impedes the transfer of knowledge between researchers of diverse linguistic backgrounds (Amano et al. 2023; Arenas-Castro et al. 2023). With English often as the second or third language, local researchers struggle and must invest more (i.e. cost, time) to produce research papers that meet the linguistic and stylistic standards of academic journals. Most do not have access or cannot afford professional editing services.

Linguistic challenges are not unique to the Pacific and a global study found that non-native English speakers spent 50.6% (median) more time writing a paper than native English speakers (Amano et al. 2023). Coupled with linguistic challenges is the capacity of educational systems in the Pacific to provide sufficient instruction in formal academic writing. Students in the region often have fewer opportunities to engage in writing-intensive programs, and an underrepresentation of Pacific scholars in global academic discourse means that there are few local role models and mentors to support the next generation in refining writing skills (Shellock et al. 2023). Without adequate mentorship, researchers (especially early-career) struggle to navigate the complex procedures required for publishing in academic journals, including adhering to rigorous methodological standards and responding to peer reviews effectively. The lack of experienced supervisors and mentors ultimately leads to lower-quality submissions (including to low impact journals) and higher rejection rates, thereby eroding researchers’ confidence and instilling feelings of inadequacy.

Improving academic writing skills among Pacific Islanders requires multi-pronged, targeted investments in education, training and mentorship (Davies et al. 2021; Shellock et al. 2023). Strengthening the foundational education system with well-trained teachers and access to high-quality learning materials focused on academic literacy is critical. This could include free or subsidised access to professional editing services that help researchers meet the linguistic and stylistic standards required by academic journals (Amano et al. 2023). Investment in teacher training programs that emphasise writing instruction and critical thinking skills can help educators better support students. Universities and research institutions in the region should also prioritise support services, such as writing centres, workshops and peer-review programs to help students and early-career researchers develop skills. Pacific researchers placed outside the academic system may be well-suited and positioned to provide training and mentorship to early career Pacific researchers if resources were available. Pairing early-career researchers with experienced Pacific academics is beneficial, fostering long-term relationships between mentors and mentees, and will allow for continued career support.

Finally, journals could consider a range of linguistically inclusive policies such as supporting publication in languages other than English, providing author guidelines in multiple languages, and instructions to editors and reviewers to review on the merit of research and avoid language biases (Arenas-Castro et al. 2023). The creation of regional peer-review or editorial panels that are familiar with the unique linguistic and cultural contexts of the Pacific could reduce the bias against non-standard English expressions and ensure that valuable research is not dismissed due to language issues. The other benefit of engaging academic reviewers from Pacific Island countries means that the use and interpretation of Indigenous or local words, concepts and contexts can be checked for accuracy. Allowing authors to use and quote local data, reports and journal articles in non-English languages would value and foster the inclusion of research conducted in other local languages (Razak et al. 2024).

Improved access to libraries and opportunities to grow academic networks

In relation to networks and publications, a challenge I have has to do with my Pacific upbringing -– it is very difficult to promote and talk about my work with others. Culturally, it can come off as rude. So we tend to talk and promote other people’s work rather than our own. This makes it difficult to find networks of people who value our work and ask us to collaborate on publications. (Ron Vave, mid-career)

The geographic isolation of many Pacific Island nations poses a substantial barrier to research publication. Many of these islands are located far from major academic centres, thereby limiting access to networks (especially subject matter experts), libraries, conferences and collaborative opportunities. Staying up to date with the latest scientific literature and discourse is difficult due to this isolation. Attending international conferences is often prohibitively expensive and many Pacific Island researchers may not have the opportunity to present work to a global audience or receive feedback from leading experts.

Establishing regional mentorship networks within the Pacific can create opportunities for local researchers to learn from each other, build confidence in inherent abilities and be inspired by people of a similar sociocultural background. Scholarship programs that fund participation in international conferences, writing retreats and research collaborations could further help Pacific researchers enhance writing abilities and contribute more effectively to academic discourse. These networks are particularly important for gaining visibility in the global academic community, where researchers often rely on connections to co-author papers, receive informal reviews and secure invitations to present research at conferences. The creation of regional research hubs or centres of excellence such as open access libraries, digital platforms and repositories that house research could help pool resources, especially research in the Pacific. For example, online platforms such as the Toksave Pacific Gender Resource aims to house all research on gender, ‘especially by researchers with Pacific heritage or deep connections to the Pacific’ (https://www.toksavepacificgender.net/).

Publication process

Removal of bias and discrimination in the peer-review process

Some reviewers see a foreign name and if they know they are not English speakers, they tend to be more critical as they start to stereotype Pacific Islanders. (Yimnang Golbuu, Palau, mid-career researcher)

Perhaps one of the largest hurdles Pacific researchers face is the publication process. Bias and discrimination, whether implicit, explicit or perceived, can pose a significant barrier for Pacific Island researchers. Studies have shown that researchers from developing nations often face higher rejection rates in prestigious journals, regardless of the quality of the research (Brodie et al. 2021; Maas et al. 2021). Reviewers and editors may harbour unconscious biases against research conducted in the Global South, perceiving this as less rigorous or relevant to the broader scientific community (Chaudhury and Colla 2021). Pacific Island research that may focus on region-specific environmental or social issues is often viewed as of limited interest to international audiences. This can result in a bias against publishing research from the Pacific, even when this addresses globally relevant topics such as climate change or biodiversity conservation. Several authors highlighted how negative reviews from editors and reviewers who were disrespectful or used unnecessarily unkind language led to an undermining of confidence as researchers.

Bias in the peer-review process is a systemic issue that needs to be addressed to ensure fair treatment of Pacific researchers. Journals should adopt double-blind review processes, in which both the authors and reviewers are anonymous, to reduce potential biases based on the author’s geographical location or institutional affiliation. While some have argued for a triple-blind process in which author identities and affiliations are also hidden from handling and chief editors (Brodie et al. 2021), we recognise that there may be added value in placing the responsibility for addressing systemic biases on these individuals, provided that systems to review and monitor progress were in place. Additionally, diversity training for journal editors and reviewers could help raise awareness of unconscious biases and promote a more equitable review process. Another strategy is for journals to include more reviewers and editors from under-represented regions (Maas et al. 2021), including the Pacific. This would provide Pacific researchers with an increased opportunity of having work reviewed by individuals who understand the regional context and recognise the value of locally relevant research. Journals could work closely with editors to investigate strategies to address publication bias and ensure fair and constructive feedback from reviewers, regardless of the author(s)’ background.

Journal policies to support under-represented groups

The University doesn’t provide any funds for publication fees. We have to find it ourselves. Even within our budget we are not allowed to put in publication fees because high-ranking journals cost a lot. This means doing a thesis by publication is extremely difficult. (Rufino Varea, early-career)

Academic journals play a crucial role in shaping the discourse and advancement of global knowledge and therefore have a responsibility to ensure equity and inclusivity. These also have a responsibility of addressing systemic biases that favour some groups – mostly men, originating from or based in wealthy institutions in the Global North, native or highly fluent English speakers and primarily white researchers (Campos-Arceiz et al. 2018; Brodie et al. 2021; Maas et al. 2021). A clear policy addressing bias, discrimination and specific support for under-represented groups (e.g. women, people of colour, non-native English speakers, etc.) is essential to create a fair, diverse scholarly environment. Arenas-Castro et al. (2023) describe several linguistically inclusive policies that journals should consider that would support Pacific researchers and other authors and readers from diverse linguistic backgrounds. The journal Conservation Letters has a specific statement on authorship:

… it is a requirement that manuscripts focused on conservation in Low and Middle Income Countries include authors from the relevant country/countries … This authorship requirement is intended to recognize contributions made by researchers, conservationists and others in the Global South that have not in the past always been acknowledged with authorship. We also believe that authorship inclusive of people from the country/countries where the research is focused will improve the accuracy of the work. As we publish in English and know this can be seen as a barrier to inclusive authorship, the list of authorship criteria above explicitly do[es] not require that all authors have contributed to writing the manuscript … Such policies can help mitigate systemic inequities, promote the inclusion of diverse perspectives, and foster a research culture that values contributions from all communities. (Society for Conservation Biology 2025)

The cost of publishing in academic journals is inhibitive for Pacific researchers. Many high-impact journals charge substantial publication fees, especially for open access options that allow the research to be freely available to the global academic community. As a result, local researchers may be limited to publishing in lower-impact journals with lower fees or opting out of open access options, limiting the visibility and impact of the research. To address this, funding agencies and academic institutions should provide financial support specifically for covering open access fees. Journals can provide options to waive fees for under-represented groups or low-income countries. Submission processes, particularly of high-impact journals, should be simplified or available in multiple languages.

Conclusion

Removing barriers for Pacific Islanders to publish research in academic journals is crucial for fostering inclusivity, promoting global scientific diversity and ensuring that valuable knowledge from the region is shared with the broader academic community. In our paper we highlight a range of barriers that Pacific researchers frequently encounter and a diversity of strategies to address these, and provide examples of the types of strategies (or solutions) needed.

These challenges faced are multifaceted, interlinked and stem from historical, socioeconomic, cultural and institutional factors. Addressing these barriers and biases in the publication processes will require concerted efforts at multiple levels, including increased investment in research infrastructure and training, greater support for Pacific Island research networks, and a more inclusive and equitable academic publishing system. We recognise that while presented separately, there are synergies and complementarities between strategies. For example, increased funding (Strategy 4) could directly facilitate time allocation for mentorship (Strategy 5), while adjustments to journal policies (Strategy 8) could synergise with peer-review reforms (Strategy 7) to create a more equitable publishing landscape. Furthermore, we deliberately refrained from ranking the proposed strategies, recognising that each holds distinct significance and relevance depending on Pacific researchers’ experience, opportunities received and career stage.

Systemic changes are unlikely to happen quickly due to inertia in the system and resistance by those in positions of power and privilege (Davies et al. 2021). However, by providing a voice for those in the Global South (de Vos et al. 2023), building networks of allies in the Global North committed to working ethically (Chin et al. 2019), and building resistance and movements for change, the global academic community can benefit from the unique perspectives and knowledge that Pacific Island researchers bring, particularly in areas such as climate change, biodiversity and Indigenous knowledge systems.

Ultimately, creating a more supportive environment for Pacific researchers will not only enhance the diversity of academic scholarship but also contribute to more robust and equitable global knowledge production. Promoting equity in research publications not only benefits Pacific Island researchers but also enriches global scholarship by incorporating diverse perspectives and knowledge systems. When afforded equitable opportunities and supportive conditions, Pacific Islanders can be leaders in research fields, contributing significantly to the academic literature. However, we must shift from isolated instances of achievement to a systemic norm.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were generated or analysed during this study.

Conflicts of interest

Sangeeta Mangubhai is an Associate Editor of Pacific Conservation Biology but was not involved in the peer review or decision-making process for this paper. The authors declare that they have no other conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all colleagues who over the years have openly shared and challenged ideas on improving the representation of Pacific Islands research and authorship in the academic literature. We are grateful to our allies and collaborators in the Global North who have encouraged us to write this piece, and P. Hannah for sharing statistics on Pacific Conservation Biology. We recognise that we are only a small subset of a larger network of local researchers and our manuscript in no way implies that we represent all of the Pacific. We hope that others will feel inspired to similarly come together to share Pacific perspectives. We hope our article improves understanding and contributes to a growing body of work calling for systemic changes in academic writing and publishing.

References

Aini J, West P, Amepou Y, Piskaut ML, Gasot C, James RS, Roberts JS, Nason P, Brachey AE (2023) Reimagining conservation practice: Indigenous self-determination and collaboration in Papua New Guinea. Oryx 57, 350-359.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Amano T, Ramírez-Castañeda V, Berdejo-Espinola V, Borokini I, Chowdhury S, Golivets M, González-Trujillo JD, Montaño-Centellas F, Paudel K, White RL, et al. (2023) The manifold costs of being a non-native English speaker in science. PLoS Biology 21, e3002184.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Arenas-Castro H, Berdejo-Espinola V, Chowdhury S, Rodríguez-Contreras A, James A, Raja NB, Dunne E, Bertolino S, Braga Emidio N, Derez C (2023) Academic publishing requires linguistically inclusive policies. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 291, 20232840.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Asase A, Mzumara-Gawa TI, Owino JO, Peterson AT, Saupe E (2022) Replacing “parachute science” with “global science” in ecology and conservation biology. Conservation Science and Practice 4, e517.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Brodie S, Frainer A, Pennino MG, Jiang S, Kaikkonen L, Lopez J, Ortega-Cisneros K, Peters CA, Selim SA, Vaidianu N (2021) Equity in science: advocating for a triple-blind review system. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 36, 957-959.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Campos-Arceiz A, Primack RB, Miller-Rushing AJ, Maron M (2018) Striking underrepresentation of biodiversity-rich regions among editors of conservation journals. Biological Conservation 220, 330-333.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chaudhury A, Colla S (2021) Next steps in dismantling discrimination: lessons from ecology and conservation science. Conservation Letters 14, e12774.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chin A, Baje L, Donaldson T, Gerhardt K, Jabado RW, Kyne PM, Mana R, Mescam G, Mourier J, Planes S, et al. (2019) The scientist abroad: maximising research impact and effectiveness when working as a visiting scientist. Biological Conservation 238, 108231.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Davies SW, Putnam HM, Ainsworth T, Baum JK, Bove CB, Crosby SC, Côté IM, Duplouy A, Fulweiler RW, Griffin AJ, et al. (2021) Promoting inclusive metrics of success and impact to dismantle a discriminatory reward system in science. PLoS Biology 19, e3001282.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

de Vos A, Cambronero-Solano S, Mangubhai S, Nefdt L, Woodall LC, Stefanoudis PV (2023) Towards equity and justice in ocean sciences. npj Ocean Sustainability 2, 25.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fidali K, Toamua O, Aquillah H, Lomaloma S, Mauriasi PR, Nasiu S, Vunisea A, Mangubhai S (2023) Can civil society organizations and faith-based organizations in Fiji, Samoa, and Solomon Islands access climate finance? Development Policy Review 41, e12728.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Harangody M, Vaughan M, Richmond L, Luebbe K (2022) Halana ka mana’o: place-based connection as a source of long-term resilience. Ecology and Society 27, 21.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Jekope Ramala M, Ruwhiu D (2024) Vakumuni vuku ni vanua (gathering the wisdom of the land): an Indigenous fieldwork research methodology in Fiji. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 65, 448-454.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kitolelei S, Thaman R, Veitayaki J, Breckwoldt A, Piovano S (2021) Na Vuku Makawa ni Qoli: Indigenous Fishing Knowledge (IFK) in Fiji and the Pacific. Frontiers in Marine Science 8, 684303.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Maas B, Pakeman RJ, Godet L, Smith L, Devictor V, Primack R (2021) Women and Global South strikingly underrepresented among top-publishing ecologists. Conservation Letters 14, e12797.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Razak TB, Budaya RR, Hukom FD, Subhan B, Assakina FK, Fauziah S, Jasmin HH, Vida RT, Alisa CAG, Ardiwijaya R, et al. (2024) Long-term dynamics of hard coral cover across Indonesia. Coral Reefs 43, 1563-1579.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Shellock RJ, Cvitanovic C, Badullovich N, Catto D, DelBene JA, Duggan J, Karcher DB, Ostwald A, Tuohy P (2023) Crossing disciplinary boundaries: motivations, challenges, and enablers for early career marine researchers moving from natural to social sciences. ICES Journal of Marine Science 80, 40-55.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Society for Conservation Biology (2025) Conservation Letters. Author guidelines. Available at https://conbio.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/hub/journal/1755263x/homepage/forauthors.html [accessed 3 January 2025]

Stefanoudis PV, Licuanan WY, Morrison TH, Talma S, Veitayaki J, Woodall LC (2021) Turning the tide of parachute science. Current Biology 31, R184-R185.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Tualaulelei E, McFall-McCaffery J (2019) The Pacific research paradigm: opportunities and challenges. MAI: A New Zealand Journal of Indigenous Scholarship 8, 188-204.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Vave R, Heck N, Narayan S, Carrizales S, Kenison D, Paytan A (2024) Impacts of commercial and subsistence fishing on marine and cultural ecosystem services important to the wellbeing of an Indigenous community in Hawai’i. Ecosystem Services 69, 101661.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |