Assessing the digital health maturity of general practice in Australia: results from a cross-sectional national survey

Tim Blake A , Debbie Passey B * , Joanne Lee A Farwa Rizvi CA

B

C

Abstract

Australia’s health system combines federal and state roles, with Primary Health Networks supporting primary care. Digital health infrastructure exists, but meaningful use and maturity are limited across general practices.

Digital health maturity was assessed across six domains: infrastructure, meaningful use, readiness, digital literacy, data literacy, and clinical leadership using a cross-sectional survey design. Between August 2020 and July 2024, 1164 general practices from 10 PHN regions were surveyed out of the 2255 practices invited to respond (31.3% of general practice clinics in Australia), this represented a 51.6% response rate.

On average, none of the general practice clinics scored above 80 out of 100 in any of the digital health maturity domains, suggesting a trend towards lower maturity. We found that low overall digital health maturity in practices is related to lower scores in meaningful use, digital health and data literacy, and clinical leadership domains.

Digital health infrastructure alone is not enough. Targeted support is essential for digital adoption. Enhancing digital health and data literacy, leadership, and tailored change management can strengthen digital adoption in practices, potentially improving care quality and digital transformation nationally.

Keywords: data literacy, digital health, digital literacy, general practice, infrastructure, leadership, meaningful use, readiness.

Introduction

General practice clinics are often the first point of contact for healthcare consumers and the foundation of the Australian healthcare system. General practice clinics support healthcare consumers across their lifespan, treat chronic conditions, and provide preventative treatments (Mengistu et al. 2023). They are also gatekeepers, providing referrals for specialty care when required (AIHW 2024). Australia’s healthcare system is a blend of public and private services, and the general practice clinics are often privately owned and standalone (not affiliated with large hospital systems) (Taylor et al. 2021). The universal Medicare Benefits Scheme (MBS) in Australia is funded by a 2% levy on taxable income above a threshold, subsidising general practice and specialist services and limited allied health services (Taylor et al. 2021). Many practitioners also charge a gap fee, adding out-of-pocket costs for patients (Duckett 2015).

The Australian health system functions through a collaborative federal–state framework, with Medicare, the national universal health insurance scheme, offering subsidised access to essential healthcare services. State governments are responsible for the administration of hospitals and public health facilities. Primary care, largely delivered through small business practices, falls under federal governance and funding. To enhance local service integration and improve health outcomes, Primary Health Networks (PHNs) play a coordinating role across primary care services (Forrester et al. 2024).

A range of digital technologies are integrated across general practice activities, including clinical information systems, appointment booking, payments, and solutions to support the provision of care and information sharing between providers (Schofield et al. 2019). Digital technologies, and the use of data associated with digital technology, have the potential to improve healthcare outcomes, the quality of care, and the efficiency of organisations providing general practice services.

The value of digital technologies to supporting the quintuple aims of health care is recognised nationally and internationally (Badr 2022; Woods et al. 2023; ADHA 2024). The extent to which digital technologies are incorporated into both clinical care and administration of general practice organisations varies (Liaw et al. 2017). Understanding the extent and nature of this variation is important for supporting general practices, and in turn the Australian community, to realise the benefits of digital technologies.

Realising the benefits of digital technologies is more than just having the technology available, it requires the appropriate capability, governance, and leadership. Digital health maturity is a holistic concept encompassing technology, operations and processes, digital strategy, digital skills, governance, compliance, and security (Chanias and Hess 2016).

Understanding the diversity of digital health maturity, including digital health literacy and data literacy among general practice clinic staff, is important for shaping policy and developing strategies to equitably improve digital health maturity. This information can be used to support improvements in digital health maturity in primary care including practical supports, policy, and implementation at the local, regional, and national level. The process of development can also be used to improve the science of digital change management in health care by arming change makers with tools to understand and analyse the current state in a structured, repeatable, and actionable way.

The aim of this study is to understand the distribution of digital health maturity in practices and describe general practice organisations at different points of their digital health maturity journey.

Methods

Study design

This study uses a cross-sectional survey design. A digital health maturity assessment was completed across 10 Australian regions in collaboration with the relevant PHNs (PHN 2023). A digital health maturity assessment involves the electronic collection of information from general practice organisations using a standardised, templated survey.

Sample size

Between August 2020 and July 2024, 1164 practices from 10 PHN regions were surveyed. Of the 2255 practices invited to respond (31.3% of general practice clinics in Australia), this represented a 51.6% response rate.

Assessment process

Participating PHNs self-identified for inclusion in the study through engagement with the digital maturity assessment, which is offered as a commercial product via consulting services. PHNs requested a digital health maturity assessment be completed for their region and provided the contact details for relevant practices. All general practice organisations within the PHN region were invited to complete the survey. A link to an online survey was circulated to all practices in the region. General practice clinic’s contact details were updated and the invitation reissued as required. New practices were also added if identified, and a number of reminders to complete the survey were issued. Reminders were only sent to those who had not completed the survey. PHNs also used direct engagement and alternative communication mechanisms (e.g. newsletters) to promote completion of the survey. Surveys were typically open for 6–8 weeks.

Informed written consent

A short consent statement was provided at the beginning of the survey explaining the purpose of the survey, how information was handled, and providing contact details for the PHN.

Participation was voluntary. Participants were required to actively consent to participate through selection of a ‘yes/no’ button. A small number of participants did not consent to participation. No further information was requested from these participants.

To conduct the survey, email addresses were collected from the PHN. Survey responses were linked to email addresses to support combining data from different surveys and to track changes overtime. Name details were requested as part of the survey to allow follow up.

Assessment questions

The digital health maturity assessment was developed by Semantic Consulting (https://www.semanticconsulting.com.au/digital-health-maturity-assessment), which holds the intellectual property. The questions are informed by previously published research, but are proprietary having gone through several iterations over a 4-year period to balance the number of questions and the information needed to provide actionable insights to general practice clinics. Digital health maturity is assessed across six domains: infrastructure; meaningful use; readiness; digital literacy; data literacy; and clinical leadership, with the readiness further broken down into the general practice clinic’s perspective on their readiness for digital change and the readiness of their patients, and the PHN’s perspective on the general practice clinic’s readiness for digital change (see Fig. 1). Information about the practice is also collected to support analysis and contextual interpretation. PHNs are provided opportunity to adjust questions to suit their particular interests and needs and in response to knowledge about their general practice community. For example, questions relating to infrastructure can be adjusted to reflect government funded systems available in that jurisdiction. Adjustments were generally minimal and fit within the established domains.

The infrastructure domain measures the extent to which information communications technology (ICT) infrastructure and digital health solutions are in place (i.e. installed and available for use). There are typically 21 scored questions in this domain, including questions regarding:

Physical infrastructure (e.g. internet, computers, ICT, and fax machine).

Privately funded software (e.g. practice management system; appointment booking; eReferrals; secure messaging; and practice intelligence tools).

Government funded systems (e.g. My Health Record; Provider Connect Australia; and HealthPathways).

The meaningful use domain measures the extent to which the practice is getting effective use out of technology and digital health solutions. This domain recognises that the presence of infrastructure is insufficient to realise the benefits of digital health and that digital tools need to be incorporated into practice. There are typically 37 scored questions in this domain.

The readiness domain measures perspectives on the readiness for digital change of various groups. Readiness is assessed from a number of perspectives including self-assessment by the practice, client assessment of the practice (which is not always known), and practice assessment of their patients. Assessing from multiple perspectives allows the practice’s view to be normalised and compared with an external perspective. There are typically 16 scored questions in this domain.

The digital literacy domain measures the general practice clinic’s perception of the digital literacy of staff. Digital literacy is the ability of someone to use digital technologies and understand their risks (Arias López et al. 2023). It refers not only to applied technical skills necessary to use and access technology, but the capacity to critically and confidently engage with it (Arias López et al. 2023). There are typically six scored questions in this domain.

The data literacy domain measures the general practice clinic’s perception of the ability of staff to interpret and apply data in decision making. Digital literacy is assessed separately to data literacy to allow for nuanced support to be provided to practices in improving their digital health maturity. It is possible to have high digital literacy and low data literacy – for example a person may easily understand how to navigate an electronic health record due to the use of accepted symbols and display structures, but they may not be able to interpret a graph or understand how a standard deviation applies to interpretation of data. Inversely, a person with statistical training and education may easily understand data presented to them but may not be able to navigate contemporary information and technology (IT) systems without intense support. There are typically eight scored questions in this domain.

The clinical leadership domain assesses the support for digital health amongst executive and clinical leaders and provides an indication of the culture influencing digital health in that general practice clinic. There are typically four scored questions in this domain.

Responses to the survey are automatically scored and weighted with analysis programmed into the survey platform. Practices are placed into an appropriate digital health maturity level depending on their survey results – Foundational; Intermediate; and Advanced. The level is a relative categorisation rather than a fixed digital health maturity score.

Survey completion

The survey questions related to the organisation as a whole and were completed by an organisational representative such as the practice manager or other individual with organisational oversight.

Recognising the time constraints and competing pressures on practice managers, the survey was designed to be completed in approximately 25 min. Survey questions were designed to be completed based on individual knowledge and without having to undertake detailed investigation of different aspects of the general practice organisation. Consequently, the majority of questions were multiple choice and used categorical responses.

Results

The characteristics of the general practice clinics completing the survey are summarised in Table 1. On average, the survey took 26.5 min to complete. Briefly, the majority of general practice clinics have been in operation over 10 years, are privately run, bulk bill, and use Best Practice (BP 2024) to manage operations. Geographic data was only available for one-third of the general practice clinics that responded to the survey and it included a mix of metropolitan, regional, rural, and remote.

| Characteristics | Number (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| How long has your practice been in operation? | ||

| 0–3 years | 140 (12) | |

| 4–9 years | 233 (20) | |

| 10+ years | 791 (68) | |

| Is your practice private or part of a corporate group? | ||

| Private | 1059 (91) | |

| Corporate group | 105 (9) | |

| What Modified Monash Model (MMM) classification is your practice? (*where data is available at a practice level) | ||

| MM1 (Metropolitan area) | 126 (34) | |

| MM2 (Regional centres) | 35 (10) | |

| MM3 – MM5 (Rural towns) | 195 (53) | |

| MM6 or MM7 (Remote or very remote) | 12 (3) | |

| How many general practitioners (GPs) are in your practice? | ||

| Solo (1 GP) | 163 (14) | |

| Small (2–5 GPs) | 477 (41) | |

| Medium (6–15 GPs) | 454 (39) | |

| Large (16 GPs+) | 70 (6) | |

| As a rough estimate, what is the average age of general practitioners in your practice? | ||

| 30s or younger | 81 (7) | |

| 40s | 524 (45) | |

| 50s | 396 (34) | |

| 60s or older | 163 (14) | |

| Are you a bulk billing practice? | ||

| Yes | 861 (74) | |

| No | 303 (26) | |

| What percentage of your patients are bulk billed? | ||

| 0–24% | 58 (5) | |

| 25–49% | 163 (14) | |

| 50–74% | 279 (24) | |

| 75–100% | 664 (57) | |

| Which practice management system does your practice use? | ||

| Best Practice | 757 (65) | |

| Medical Director | 279 (24) | |

| Zedmed | 47 (4) | |

| Genie | 12 (1) | |

| Helix | 12 (1) | |

| Communicare | 12 (1) | |

| MediRecords | 10 (<1) | |

| Other | 35 (3) | |

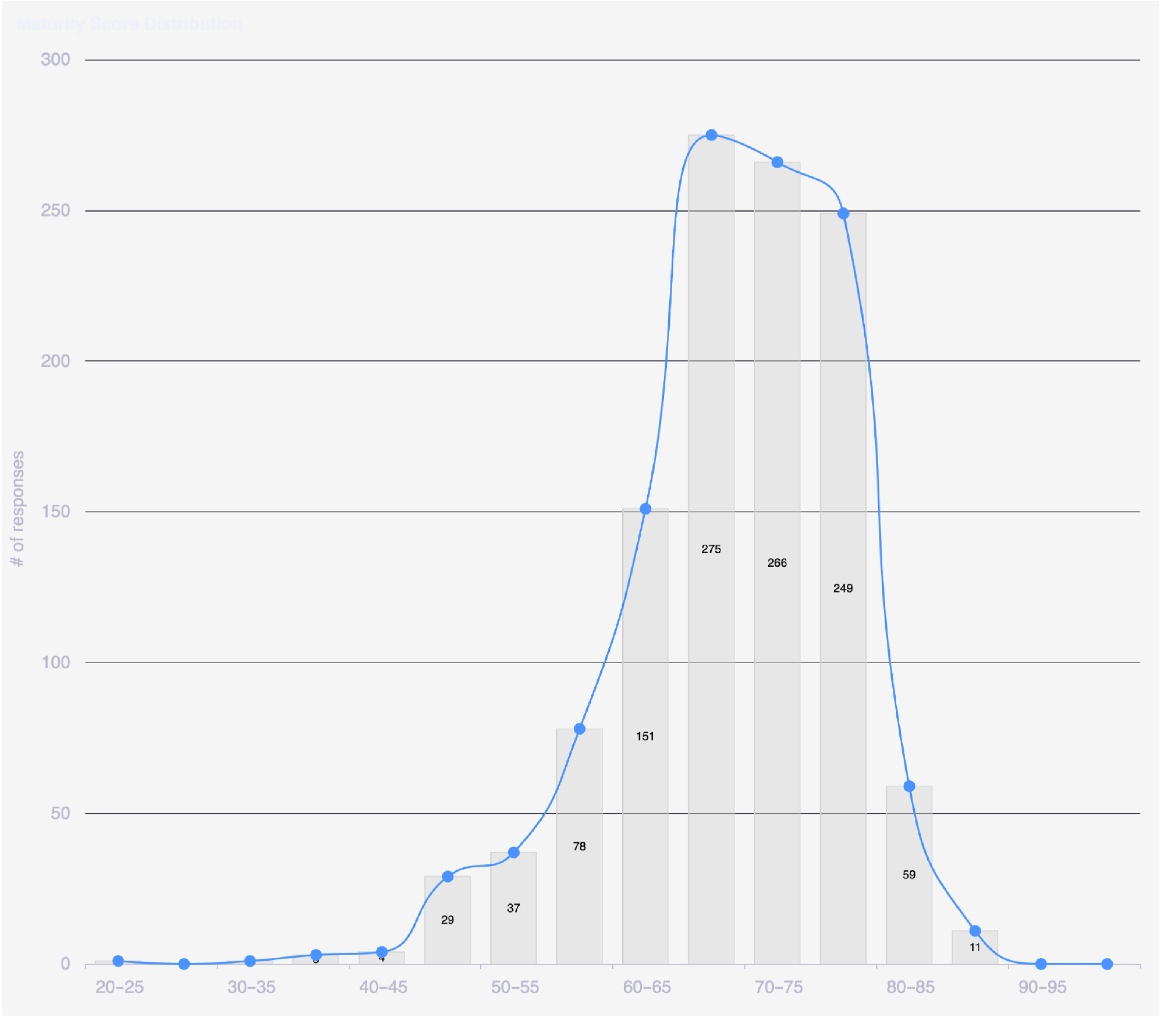

The mean digital health maturity score across general practice clinics was 69.5 (out of 100) with a standard deviation of 8.1. The responses followed a normal distribution, with a slight skew towards lower maturity scores (see Fig. 2). The digital health maturity profiles have been categorised into Foundational, Intermediate, and Advanced based on a number of standard deviations from the mean.

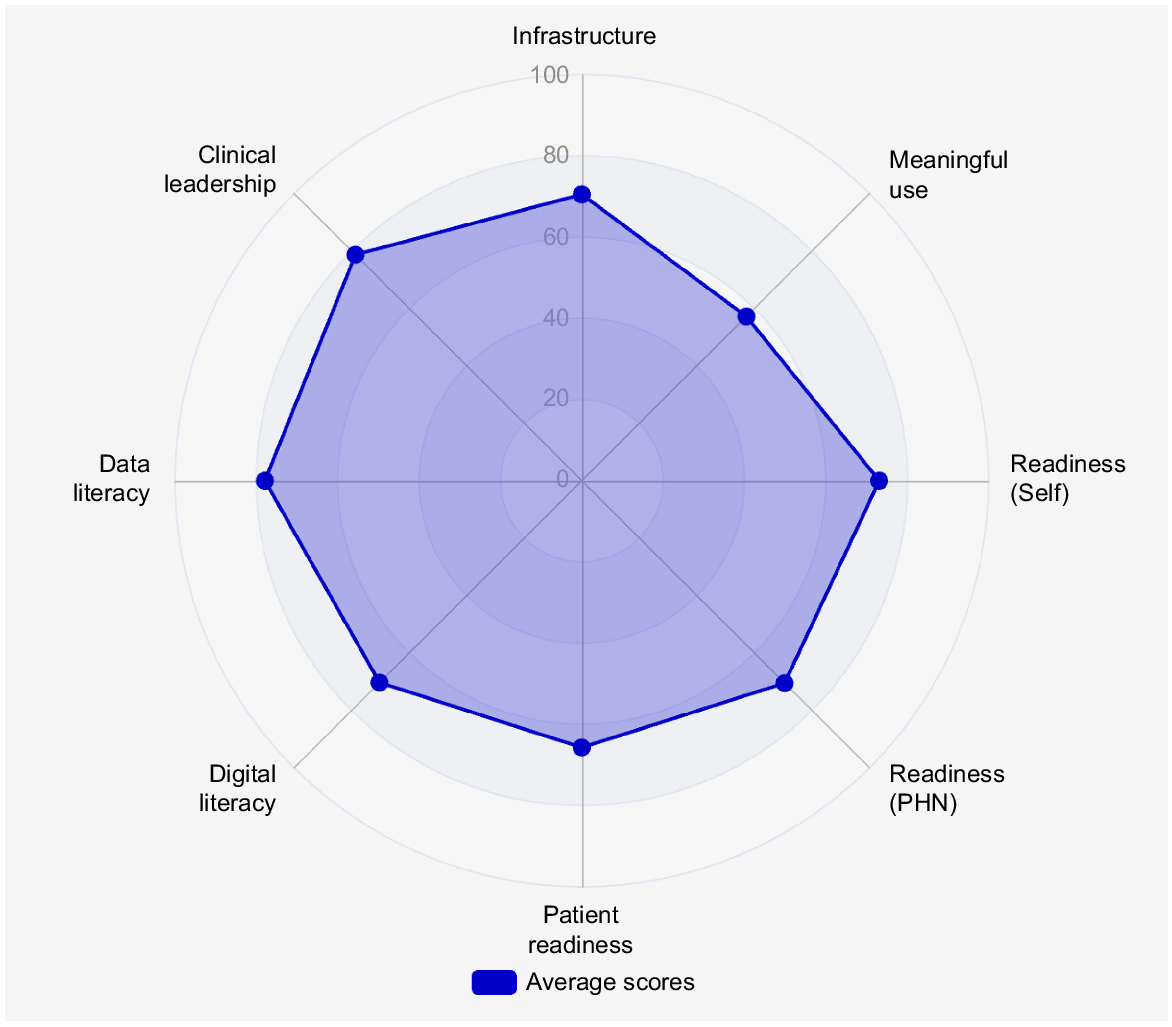

The average digital health maturity scores by domain area are summarised in Fig. 3. On average, the general practice clinics did not score above 80 out of 100 in any of the domains, suggesting a trend towards lower digital health maturity. Infrastructure and meaningful use had the lowest average scores across the general practice clinics, indicating less capability to fully leverage digital health technology. Readiness (self-assessed, practice and patient) were also lower, which suggests change management strategies may be warranted.

Digital health maturity in general practice can be characterised by a number of distinctly (qualitatively) different states. The variability in digital health maturity in general practice clinics is meaningful. We found that general practice clinics across the spectrum of digital health have distinct profiles. Table 2 provides a summary of survey results by digital maturity level. Foundational practices are generally those without digital infrastructure and require support to understand the value of investing time and resources into purchasing and implementing these products. Intermediate practices generally have infrastructure in place but are not using these tools to full effect. General practice clinics in the Advanced category generally understand the value of digital health and have independently implemented digital initiatives.

| Number (%) of practices at this level of maturity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Foundational n = 232 (20) | Intermediate n = 678 (58) | Advanced n = 254 (22) | |

| Characteristics of practices at this level of maturity | |||

| • Digital health solutions may be in place, but usage is poor | • Digital health solutions typically in place, usage is average | • Digital health solutions in place, and usage is good | |

| • Little to no diffusion of digital health solution across clinicians in the practice | • Little diffusion of digital health solution across clinicians in the practice | • Reasonable diffusion of digital health solution across clinicians in the practice | |

| • Limited understanding of the role of digital health and its relationship to quality of care and General Practice sustainability | • Average understanding of the role of digital health and its relationship to quality of care and general practice sustainability | • Stronger understanding of the role of digital health and its relationship to quality of care and general practice sustainability | |

| • Poor motivation to use digital health and data | • Some motivation to use digital health and data, but not strong and future progress is not guaranteed | • Good motivation to use digital health and data | |

| • Often have poor digital and data literacy | • Reasonable digital literacy, although data literacy is still variable | ||

| • Typically, smaller practice size | |||

| • Typically, older average age of general practice | • Average digital literacy but still poor data literacy | • Typically, larger practice size | |

| • More likely to bulk bill at higher rates | • Typically, average practice size | • Typically, younger average age of general practice | |

| • Less likely to use Best Practice | • Less likely to bulk bill at higher rates | ||

| • More likely to use Best Practice | |||

Discussion

Although digital health infrastructure uptake is reasonably good, meaningful use of digital health solutions remains poor even among the Advanced practices, meaning that digital health has not been strongly adopted in general practice clinics (Arias López et al. 2023). Most general practice clinics have infrastructure, such as secure messaging, electronic referrals, and electronic prescriptions. Yet, they are still far from making full use of this infrastructure.

For example, although telehealth platforms are in place, many practices still use the telephone as the primary form of telehealth provision (Raza Khan et al. 2019). Additionally, IT operations were often outdated. For example, only around 50% of practices back up their data to cloud storage, and a high proportion (70%) use on premise servers for their practice management system, which is associated with cyber-security and disaster recovery risks.

Our study indicates that those in the Foundational group were more likely to not understand their privacy and security obligations so require support in these areas to ensure safe implementation. Significant differences were reported between conceptual understanding of issues and day to day practices, highlighting the importance of measuring both aspects of a domain. For example, although nearly all practices agree that staff have a good awareness of cyber-security and appropriate practices for keeping data secure, this is inconsistent with behaviour reported such as sharing of logins and written storage of passwords (notebooks or word documents). Similarly, although practices report staff have a good understanding of their obligations under the Australian Privacy Act, many still send patient information via email.

We found that implementation of digital health infrastructure is not a good predictor of digital health maturity. Although digital health infrastructure uptake is reasonably good, often reflecting government incentives, meaningful use of digital health solutions remains poor, reflecting that infrastructure is insufficient to achieve change. A key factor impacting digital maturity is clinical leadership: digital change succeeds in environments where data and digital are perceived as part of the delivery of care, not just administrative activities. This is in line with previous research that suggests that the culture and climate of an organisation and clinical leadership can hinder or facilitate the implementation of digital health technology (Greenhalgh et al. 2019; Braithwaite et al. 2024).

A key differentiator for digital health maturity was whether data are seen as important for clinical usage and not just administrative purposes. Where general practice clinics support this statement, they are more likely to have a higher overall digital health maturity score. Similarly, the impact of clinical leadership on adopting and using digital technologies was significant for realising meaningful use. This suggests that the cultural and organisational context is important for realising digital transformation. Previous research has shown that executive leadership support for adopting innovations is important, and that frontline and middle manager perceptions that the innovation fits within their workflow is also important for adoption (Cresswell et al. 2013; Fylan et al. 2022).

Strengths of this study include the robustness of data. Invites to the survey covered 30% of general practice clinics in Australia, and 50% of those responded. A response rate of 50% is considered good for survey studies. Another strength is the thoroughness of the digital maturity assessment and the linkage of the survey questions to actionable insights. This supports multiple levels of intervention (PHN, general practice clinic, and individual provider) to facilitate meaningful change. There are some limitations to this analysis. The data come from a cross-sectional survey, which is susceptible to nonresponse bias and recall bias. The question set was constrained to be a 30-min survey in order to encourage a higher level response. This study only included private general practice clinics and did not include community health centres or other care models. This study was unable to consider how rurality and remote regions might affect practice uptake, readiness, or capability for digital innovation. Although the diversity of geographic variation could not be considered in this paper, future research will explore this area along with digital literacy and capability.

Conclusion

Implementation of digital health infrastructure alone is not a good indicator of digital health maturity. The extent of meaningful use should be considered as a better predictor. Approaches to digital change management should be tailored to meet general practice clinics where they are along the digital health maturity spectrum. Additionally, strategies for improving digital health literacy and data literacy of general practice clinics could greatly improve meaningful use. National policy should address concerns related to digital and data literacy, as well as urgent issues of IT hygiene such as cyber-security, disaster recovery, and backup.

Recommendations

To tailor the approach to digital change management based on need, which can be characterised by a number of distinct ‘maturity states’ along the digital health maturity spectrum.

To meet GP practices where they are at in digital health maturity.

To develop strategies for improving digital and data literacy.

To acknowledge the need for national policy and action around key systemic areas of need (e.g. cyber-security, approach to disaster recovery, and backup, etc.)

Data availability

De-identified aggregated data is available for review. However, identifiable data is not available due to privacy policy and consent statements with individual PHNs, which state that identifiable data will not be shared.

Declaration of funding

This work was funded through a series of contracts with Australian Primary Health Networks (PHNs). Each PHN contracted Semantic Consulting (TB, JL) to run a digital health maturity assessment across their region. Beyond this, the other researchers (DP, FR) did not receive any specific funding and provided in-kind support for the analysis and preparation of the article.

Author contributions

All authors discussed the results and reviewed and commented on the manuscript. TB designed the study, contributed to collecting data, reviewing the results, and to writing of the manuscript. DP contributed to reviewing the results and to writing of the manuscript. JL contributed to collecting data, reviewing the results, and to writing of the manuscript. FR contributed to designing the manuscript, reviewing the results, writing of the manuscript, and reference management.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the PHNs, practice managers, practice owners, general practitioners, and staff of the general practices for their participation in this study.

References

ADHA (2024) National digital health strategy 2023–2028. Australian Digital Health Agency. Available at https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/national-digital-health-strategy [accessed 26 October 2024]

AIHW (2024) Primary Health Care. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/health-welfare-services/primary-health-care/overview [accessed 26 October 2024]

Arias López MdP, Ong BA, Borrat Frigola X, Fernández AL, Hicklent RS, Obeles AJT, Rocimo AM, Celi LA (2023) Digital literacy as a new determinant of health: a scoping review. PLoS Digital Health 2, e0000279.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Badr N (2022) Technology for quintuple aim: evidence of technology innovations in reaching the aim of health equity. Available at https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=itais2022 [accessed 26 October 2024]

BP (2024) Best Practice Software. BP Partner Network-An Extensive Network of Third Party Integrations. Available at https://bpsoftware.net/ [accessed 10 November 2024]

Braithwaite J, Leask E, Smith CL, Dammery G, Brooke-Cowden K, Carrigan A, Mcquillan E, Ehrenfeld L, Coiera E, Westbrook J, Zurynski Y (2024) Analysing health system capacity and preparedness for climate change. Nature Climate Change 14, 536-546.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chanias S, Hess T (2016) Understanding digital transformation strategy formation: insights from Europe’s automotive industry. In ‘20th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, PACIS 2016 Proceedings’, 27 June–1 July, Chiayi, Taiwan. Available at https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2016/296

Cresswell KM, Bates DW, Sheikh A (2013) Ten key considerations for the successful implementation and adoption of large-scale health information technology. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 20, e9-e13.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Duckett S (2015) Medicare at middle age: adapting a fundamentally good system. Australian Economic Review 48, 290-297.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Forrester B, Fisher G, Ellis LA, Giddy A, Smith CL, Zurynski Y, Sanci L, Graham K, White N, Braithwaite J (2024) Moving from crisis response to a learning health system: experiences from an Australian regional primary care network. Learning Health Systems 9, e10458.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Shaw S, Papoutsi C, Vijayaraghavan S, Stones R (2019) Infrastructure revisited: an ethnographic case study of how health information infrastructure shapes and constrains technological innovation. Journal of Medical Internet Research 21, e16093.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Liaw S-T, Kearns R, Taggart J, Frank O, Lane R, Tam M, Dennis S, Walker C, Russell G, Harris M (2017) The informatics capability maturity of integrated primary care centres in Australia. International Journal of Medical Informatics 105, 89-97.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Mengistu TS, Khatri R, Erku D, Assefa Y (2023) Successes and challenges of primary health care in Australia: a scoping review and comparative analysis. Journal of Global Health 13, 04043.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

PHN (2023) Primary Health Networks. DHAC, Australia. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/phn [accessed 26 October 2024]

Schofield P, Shaw T, Pascoe M (2019) Toward comprehensive patient-centric care by integrating digital health technology with direct clinical contact in Australia. Journal of Medical Internet Research 21, e12382.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Taylor A, Caffery LJ, Gesesew HA, King A, Bassal A-R, Ford K, Kealey J, Maeder A, Mcguirk M, Parkes D, Ward PR (2021) How Australian health care services adapted to telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of telehealth professionals. Frontiers in Public Health 9, 648009.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Woods L, Eden R, Canfell OJ, Nguyen K-H, Comans T, Sullivan C (2023) Show me the money: how do we justify spending health care dollars on digital health? The Medical Journal of Australia 218, 53-57.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |