An integrative review of missed nursing care and the general practice nurse

Eileen Willis A B , Claire Verrall C * , Susan McInnes D and Elyce Pate C

C * , Susan McInnes D and Elyce Pate C

A

B

C

D

Abstract

The phenomenon of missed care has received increasing interest over the past decade. Previous studies have used a missed care framework to identify missed nursing tasks, although these have primarily been within the acute care environment. The aim of this research was to identify missed care specific to the role of the general practice nurse.

An integrative review method was adopted, using The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool to assist in a methodological appraisal of both experimental, theoretical, and qualitative studies. Thematic analysis was then used to analyse and present a narrative synthesis of the data. Data sources: CINAHL, SCOPUS, Web of Science and Google Scholar databases were searched between 2011 and 2022 for empirical research that reported missed care and the general practice nurse.

Of the 787 papers identified, 10 papers met the inclusion criteria. Three themes identified missed care in relation to primary healthcare nurses: under-staffing and resourcing, communication difficulties, and role confusion.

Isolating missed care by general practice nurses was challenging because much of the research failed to separate out general practice nurses from community and primary health care nurses. This challenge was exacerbated by disparity in the way that a general practice nurse is defined and presented in the various databases. While some themes such as those related to communication and understaffing and resourcing demonstrate some parallels with the acute sector, more research is required to identify missed care specific to the general practice nurse.

Keywords: clinic, community, family practice, general practice, missed care, practice nurse, primary care, primary health care.

Introduction

For nearly 20 years, nurses across the globe have highlighted the problem of missed nursing care (Kalisch 2006; Blackman et al. 2014; Bragadóttir et al. 2016). The issue was first formally raised by Kalisch in the USA, who developed the MISSCARE survey (Kalisch et al. 2009), and Schubert working with a team from the RN4Cast group from hospitals in nine countries in Europe who made a distinction between implicit (missed care) and explicit rationing (prioritising or staking) (Schubert et al. 2008; Ebright 2010; Ludlow et al. 2020). The classic definition of missed nursing care is provided by Kalisch as: any aspect of required patient care that is omitted (either in part or in whole) or delayed (Kalisch et al. 2009, p. 1510). Since these earlier studies, research into missed nursing care has accelerated across the world, culminating in a major European funded program between 2016 and 2020 (Papastavrous et al. 2016). An increase in research publications has produced consistent results, identifying staffing levels, skill mix and resource deficits as major causative factors, irrespective of country, the organisation of the healthcare system or specialty (Cho et al. 2015; Verrall et al. 2015; Zuniga et al. 2015; Blackman et al. 2020a).

Both the Kalisch and RN4Cast studies focused on acute hospital surgical and medical wards (Schubert et al. 2009; Schubert et al. 2013; Palese et al. 2015). Subsequent research went on to explore missed care in neonatal intensive care settings (Tubbs-Cooley et al. 2015), residential aged care (Blackman et al. 2020b), rehabilitation wards (Buchini and Quattrin 2012), during hospital mergers or in relation to differences in staffing levels, skill mix and the COVID-19 pandemic (Castner et al. 2014; Dabney and Kalisch 2015; Labrague et al. 2022). Missed care has also been examined across varied models of nursing care (Moura et al. 2020), cross culturally (Zelenikova et al. 2019), from the patient’s perspective (Dabney and Kalisch 2015), as well as across various shift times (Blackman et al. 2015). Studies from Israel have examined the relationship between nurse personality traits and missed care (Drach-Zahavy and Srulovici 2019), while other researchers have explored the impact of team work (Kalisch and Kyung 2010) and nurse unit managers’ perceptions of missed care (Dehghan-Nayeri et al. 2018). A small number of studies have explored the concept of missed care in community settings such as nursing homes, outreach aged care programs and mental health (Phelan and McCarthy 2016; Phelan et al. 2018). These studies capture community nursing, although fail to separate the broad range of roles played by nurses in these settings (Poghosyan et al. 2017; Senek et al. 2021).

In Australia, the term practice nurse refers to ‘a registered or enrolled nurse employed in a primary care (general practice) setting’ (Guzys et al. 2021, p. 390). Internationally, these nurses are known as practice nurses in the United Kingdom and New Zealand; however, in Canada, they are known as primary care nurses, family practice nurses or registered practical nurses (Verrall et al. 2023). In the USA, nurses working in general/family practice are often nurse practitioners. These nurse practitioners are part of a larger group of nurses known as advanced practice registered nurses, again adding to the confusion. In Ireland, nurses working within general practice are known as practice nurses, in addition, there are nurses who work in the community as well as public health nurses who have a graduate qualification in public health nursing and care for whole population coverage (cradle to the grave).

While the aim of this review focuses on missed nursing care within general/family practice, we note the challenges posed when extrapolating missed care specific to the role of the general practice nurse.

Methods

The synthesis and critical review of empirical literature was guided by the integrative review methods described by Whittemore and Knafl (2005). Integrative reviews contribute to evidence based nursing by adopting a robust and systematic process to search and synthesise diverse methodologies (Whittemore and Knafl 2005). This type of review was specifically chosen as it goes beyond analysis and synthesis of findings to provide new insights related to a specific phenomenon (Lubbe et al. 2020). The phenomenon explored for this research was missed nursing care within the general practice context and, according to Lubbe et al. (2020), an integrative review is especially important in identifying future research by bridging related areas of work and identifying central issues.

Search strategy

An initial search of the CINAHL database using the search term ‘practice nurse’, and terms known to be aligned with missed care is shown below:

TI ‘practice nurse*’ OR AB ‘practice nurse*’

AND

TI (missed OR omitted OR undone) OR AB (missed OR omitted OR undone)

NOT

TI ‘advanced practice nurse*’ OR AB ‘advanced practice nurse*’

This search yielded 28 results. Given that the term ‘advanced practice nurse’ does not relate directly to the general practice nurse role, this was excluded. A manual search of the 28 articles revealed that none specifically separated out general practice nurses in reporting missed care or if they did so, not all s in the research sites participated. As a consequence, it was then decided by the team to employ a wider search strategy as seen below.

The international literature was searched in CINAHL, SCOPUS, Web of Science and Google Scholar databases by applying the following search terms:

nurse or nurses or nursing

AND primary health care OR primary care OR general practice OR family practice OR community

missed OR omitted OR undone.

The following provides an example of how the search terms were used when using the SCOPUS database:

(TITLE-ABS-KEY (nurse OR nurses OR nursing) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (primary AND health AND care) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (primary AND care) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (family AND practice) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (community) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (missed OR omitted OR undone) AND NOT TITLE-ABS-KEY (hospital OR acute OR inpatient OR ward) AND NOT TITLE-ABS-KEY (aged OR home OR residential) AND NOT TITLE-ABS-KEY (icu OR nicu OR oncology)) AND PUBYEAR > 2010 AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA, “NURS”))

Articles were screened via titles, abstracts and full text against the inclusion criteria and appraised for methodological quality. Table 1 presents the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Articles written in English | Articles not written in English | |

| Articles published from 2011–2022 (December) | Articles published prior to 2011 | |

| Primary, peer reviewed research | Articles that were not peer reviewed, primary research such as Editorials and Commentaries | |

| Full text available | Full text not available | |

| General practice, family practice, community, primary health care, advanced practice nurse | Aged care, nursing home, residential aged care facility, hospital, acute, inpatient, ward | |

| Nurse, practice nurse | General practitioner, nurse assistant |

Reference lists were examined for additional relevant papers. Nursing in primary care is rapidly evolving, and to ensure contemporary literature was captured, the search was limited to the period 2011–2022.

Empirical peer reviewed research that reported missed nursing care in primary care settings was included only where the role of the general practice nurse was identified, and where full text was available in English through institutional repositories. Discussion papers, reviews, reports and editorials were excluded, as were papers that only reported missed care in acute care settings, aged care or mental health facilities.

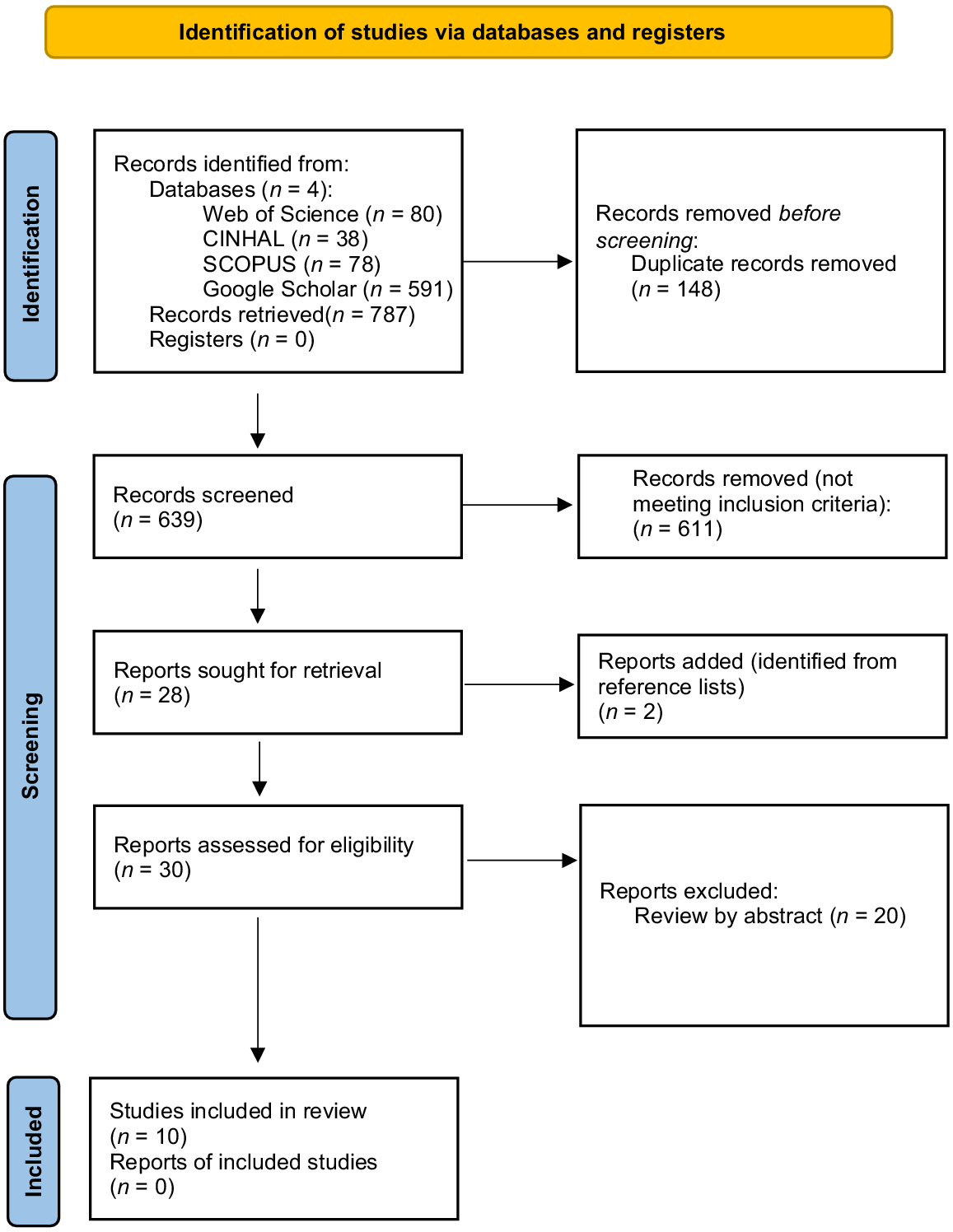

The database search identified 787 papers. Papers were imported into Endnote X9™ (Clarivate Analytics, 2020), where duplicates were removed (n = 148). One author (SM) assessed the titles of the remaining papers (n = 639) against the inclusion criteria resulting in the removal of 611 papers. Two papers were added by title after review of reference lists. A review of abstracts (n = 30) by two authors (EW and CV) excluded an additional 20 papers. All authors agreed that the remaining 10 papers met the inclusion criteria to undergo full analysis.

The methodological process identified above is presented in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) diagram shown in Fig. 1.

Data abstraction and synthesis

Data from the remaining 10 papers were extracted into a summary table by the first author (SM) and confirmed by all members of the research team (Table 2). Due to diverse methodologies applied across papers, thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (2006) was used to aggregate findings and present a narrative synthesis of the data. The first author (EW) undertook the initial synthesis and identified the preliminary themes, with all authors reaching consensus on the development of final themes.

Author/s | Title | Country | Aim | Sample/context | Method | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Characteristics of recovery from near misses in primary health care nursing: A prospective descriptive study | Spain | To describe the frequency and types of near misses and the recovery strategies employed by nurses in primary health care | Four nurses working in an urban primary healthcare centre | Quantitative Non-experimental prospective descriptive study (questionnaire) |

| ||

Use of six sigma for eliminating missed opportunities for prevention services | USA | To determine if delivery of preventative services could be increased by changing nursing protocols | Number of nurses not specified One medical practice setting only | Quantitative and qualitative Patient interviews/data from medical records |

| ||

Primary care providers’ perspectives on errors of omission | USA | To develop a typology of errors of omission from the perspectives of primary care providers (PCPs) and understand what factors within practices lead to or prevent these omissions | 12 physicians and 14 nurse practitioners from several primary care practices (PCPs) | Qualitative interviews |

| ||

The impact of COVID-19 on primary health care delivery in Australia | Australia | To validate the ‘safe and effective staffing tool’ and explore the impact of COVID-19 on the quality of Australian primary health care | 359 primary healthcare nurses 167 were employed in general practice | Quantitative Survey |

| ||

Test result communication in primary care: clinical and office staff perspectives | UK | To understand how the results of laboratory tests are communicated to patients in primary care and perceptions on how the process may be improved | Seven registered nurses and three healthcare assistants, four primary care practices | Qualitative Focus groups |

| ||

Nursing care left undone in community settings: results from a UK cross-sectional survey | UK | To demonstrate the prevalence of care left undone and its relationship to registered nurse staffing levels within community nursing | 3009 registered nurses (community and care home) | Quantitative Cross sectional survey |

| ||

Missed care in community and primary care | UK | To explore the prevalence of missed care in community and primary care settings, and to better understand its association with staffing levels | 3009 registered nurses (community and care home) | Quantitative Cross sectional survey | In primary care and the community, 63% of shifts were understaffed In primary care and the community, missed care was significantly more likely to occur on understaffed shifts (39%) compared to fully staffed shifts (23%) (P < 0.01) Practice nurses reported fewer episodes of missed care compared to community or district nurses 318 were practice nurses and 32% categorised their shifts as understaffed 23% of practice nurses said they missed care (in understaffed categories) while in well-staffed categories, 61% did not miss care | ||

Community nursing in Ireland | Ireland | To identify levels of missed care among practicing public health nurses (PHNs) and community registered general nurses (CRGNs) | 283 PHNs and CRGNs | Quantitative |

| ||

Examining missed care in community nursing: a cross section survey design | Ireland | To examine the prevalence of missed care in community nursing | 458 community nurses | Quantitative survey |

| ||

Examining the context of community nursing in Ireland and the impact of missed care | Ireland | To identify the quantity of, and reasons for, missed care | 283 community nurses | Qualitative interviews |

Quality appraisal

Retrieved literature were independently appraised by two authors (CV and EP) using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al. 2018). The MMAT is a validated tool to appraise methodological quality across qualitative, quantitative, randomised control trials, non-randomised trials and mixed methods studies (Hong et al. 2018). The tool has been used extensively in the health sciences and to report methodological quality in primary healthcare integrative reviews (Stephen et al. 2018; Doherty et al. 2020; McInnes et al. 2022). Only minor quality issues were identified, for example, the representative sample size of the target population was small in one paper (Vázquez-Sánchez et al. 2020). Consistent with the MMAT, no paper was excluded based on methodological quality (Hong et al. 2018).

Results

The search yielded 10 papers suitable for review: one from Spain, two from the USA, three from the UK, one from Australia and three from Ireland. Six papers used quantitative methods, three were qualitative and one mixed. Analysis from the review presents those tasks identified as missed with associated rationales. This is followed by a discussion of the following identified themes: under-staffing and resourcing, communication difficulties and role confusion.

In most cases, the nurse researchers modified the survey protocol to more readily match the realities of general or family practice nursing, and in many cases the cohort of those surveyed was wider than nurses working in general or family practices (Phelan and McCarthy 2016; Phelan et al. 2017; Halcomb et al. 2021). Given this, it was necessary to tease out specific general practice nurse tasks from those of community health nurses. Tasks missed ranged from administrative or communication gaps, to medication errors (Vázquez-Sánchez et al. 2020), failure to provide preventative care such as education, health promotion or counselling (Gittner et al. 2015; Phelan and McCarthy 2016; Poghosyan et al. 2017), liaising with other health professionals (Phelan and McCarthy 2016), patient follow-up, documentation (Phelan and McCarthy 2016; Poghosyan et al. 2017), paediatric assessments and immunisation (Phelan and McCarthy 2016), mental health screening (Poghosyan et al. 2017) and responding to patient specific concerns (Poghosyan et al. 2017). Several studies gave the rates for missed care (Gittner et al. 2015; Phelan and McCarthy 2016; Phelan et al. 2017, 2018; Senek et al. 2020, 2021; Vázquez-Sánchez et al. 2020; Halcomb et al. 2021). However, the diversity of study designs made it difficult to compare these studies. There were reports on increased missed care, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic for those patients with chronic conditions (Halcomb et al. 2021), for refugees and the homeless (Phelan and McCarthy 2016; Phelan et al. 2017) and the uninsured (Gittner et al. 2015). Some studies reported that general practice nurses were less likely to miss care compared to other community-based nurses (Halcomb et al. 2021; Senek et al. 2020, 2021).

Three themes identifying the reasons for missed care were evident in the 10 studies.

Under-staffing and resourcing

Six authors identified under-staffing as a major factor for missed nursing care (Gittner et al. 2015; Phelan and McCarthy 2016; Phelan et al. 2017; Senek et al. 2020, 2021; Vázquez-Sánchez et al. 2020), noting that caseloads were too high (Phelan et al. 2018) and the time with patients too short (Poghosyan et al. 2017). Tasks missed increased when staffing was inadequate (Senek et al. 2020, 2021). Two studies noted that staff numbers, along with the nurses age, experience and working time, impacted on the number of tasks that were missed (Halcomb et al. 2021; Phelan and McCarthy 2016). Closely aligned to staffing was resource scarcity. This included lack of support staff (Poghosyan et al. 2017). None mentioned resources such as computers or medical equipment as a resource issue.

Communication difficulties

Communication was identified as a major issue. These issues were sometimes caused by interruptions from other health professionals or family (Vázquez-Sánchez et al. 2020), or the nurse being forced to perform non-nursing duties (Halcomb et al. 2021), or having to communicate test results across platforms or between practices (Litchfield et al. 2014). Where communication was sound, fewer omissions occurred (Poghosyan et al. 2017).

One study examined the problem of failing to communicate test results to patients, and identified a lack of adequate protocols as the key culprit (Vázquez-Sánchez et al. 2020). In this study, the researchers found that practices lacked a method for ensuring that patients received their test results, particularly when all was well, or when the results had been held up at a laboratory. According to Vázquez-Sánchez et al. (2020), there was no clear identification for which member of the healthcare team had ultimate responsibility for communicating results to patients. The authors found that there was often no routine method for communicating test results and if the patient did not call back, the results were often not reported (Litchfield et al. 2014; Vázquez-Sánchez et al. 2020).

Role confusion

Closely aligned to communication difficulties was role confusion. Phelan et al. (2018) highlighted a lack of understanding of the various roles of community nurses and postulated that this role confusion could contribute to the potential invisibility of the work done by some community nurses. Role confusion was highlighted by Litchfield et al. (2014), concluding that clear role delineation and communication protocols could ensure that staff were aware of their responsibilities and help reduce potential for error. Gittner et al. (2015) stressed that preventative service delivery was not always a routine part of all nurses roles and according to Vázquez-Sánchez et al. (2020), a lack of understanding of each other’s roles contributed to anxiety about approaching the doctor about a task not completed.

Senek et al. (2021) reported that general practice nurses experienced more missed care than community or district nurses and postulated that this may be due to the controlled nature of their work. However, the specificity of this was lacking and this finding differs from the Halcomb et al. (2021) Australian findings.

Two studies by Phelan and colleagues extended beyond those working in general practice, to include nurses undertaking home visits for patients with chronic illness, refugees, the homeless and travellers, again, illustrating the challenges of the various nomenclatures attributed to the primary healthcare nurse, specifically the general practice nurse (Phelan and McCarthy 2016; Phelan et al. 2017). In some cases the work of the general practice nurses was separated out from that of other nurses (Poghosyan et al. 2017), while in others, similar to the Irish studies, the rates of missed care of all nurses working in community settings were reported as one group (Senek et al. 2020).

Significantly, these 10 studies were not as uniform in research design as many of those done in the acute sector in medical or surgical wards (Kalisch and Kyung 2010). For example in the Spanish study, only four of the 10 nurses in the practice agreed to take part, and there was an electronic system already in place to measure care omissions which was not used (Vázquez-Sánchez et al. 2020). Another study trialed a health promotion/education intervention and recorded the omissions in care, nominating the differences between the intervention and the care-as-usual group (Gittner et al. 2015). In some cases, missed care was the responsibility of the doctor, but nurses failed to alert them to this. This same study reported differences in medical and nursing omissions given the varied skills set (Vázquez-Sánchez et al. 2020). An interesting factor in one study was the fact that doctors were held accountable for preventative care, but nurses were responsible for performing the tasks.

Discussion

Ascertaining specific data about missed care and the general practice nurse is problematic. Reasons for this are three-fold; firstly, the nomenclature used to describe a general practice nurse varies between countries. In many instances, general practice nurses are positioned under the umbrella of community nurses, primary healthcare nurses or public health nurses, adding to the challenge of isolating the general practice nurse role and associated missed care. Secondly, an advanced practice nurse has been defined by the Australian College of Nursing as ‘… a leader in nursing and health care … enabled through education at master’s level’ (ACN 2019, p. 6). This term is also used in the USA as an overarching term to which nurse practitioners belong. In addition, despite having different skill sets and scope of practice, there is confusion between the roles of a general practice nurse and nurse practitioner (Madahar 2015). Thirdly, this variation in terminology coupled with role confusion has culminated in barriers to searching databases to elicit specific general practice nurse missed care. Searching subject headings such as community health nurse, practice nurse and family practice nurse provided the research team with a greater opportunity to locate papers specific to the general practice nurse. This was necessary given that the term ‘practice nurse’ is often confused with the terms ‘practical nurse’ and ‘advanced practice nurse’ which can relate to nurses working in a variety of contexts besides general practice clinics. The confusion related to the lack of well-defined terms coupled with the variety of terms used to describe advanced practice nurses internationally has been highlighted by Dowling et al. (2013). These authors go on to say that while the term ‘advanced practice nurse’ is synonymous with a ‘clinical expert’, consensus on terminology and definitions is integral to any global advancement of the nursing profession (Dowling et al. 2013). This confusion added to our challenge and the inability to extrapolate data specific to missed care and the role of the general practice nurse.

Much of the available data groups ‘community/PHC’ nurses together under the one umbrella, adding to the difficulty of extrapolating missed care specific to the general practice nurse. This has resulted in the general practice nurse often being included in research surveys and questionnaires that calculate missed care that may be inaccurate for the general practice context. For example, in a study by Halcomb et al. (2021), their survey of 359 PHC nurses included 167 general practice nurses, with information provided on the number of nurses, but the study did not highlight the specificity of the general practice nurse role.

An issue not identified, but appears elsewhere in the research literature, is the range of tasks undertaken by general practice nursess. In Australia at least, there does not appear to be a standardised role description with many arguing that the general practice nurse role is determined by their relationship with the general practitioner (McInnes et al. 2015).

Studies focusing primarily on the acute sector have identified the antecedents of missed care under the following headings: unit level, nurse level and patient level (Chiappinotto et al. 2022). This study identified resource and staff scarcities from a unit or hospital perspective, along with communication issues and role confusion. Within general practice, these issues are related to the nature of the practice and research related to the ownership or governance of a general practice is yet to be conducted. There are similarities in how communication failures contribute to missed care in both sectors; however, role confusion is less of a factor.

Resource and staff scarcities, along with communication issues have been associated with missed care in the acute sector, (Verrall et al. 2015). However, while nurses in the acute sector indicated issues with communication, there were few instances reported on role confusion. In addition, findings from the acute sector show that nurses are less likely to miss tasks linked to doctors’ orders than those linked to activities of daily living (Bragadóttir et al. 2016).

Conclusion

This integrative review culminated in the identification of research articles identifying missed nursing care within the primary health care/community sector. However, as noted above, the studies failed to separate out general practice nurses from other community nurses or failed to identify specific care tasks missed by these nurses. Furthermore, in studies that focused solely on general practice nurses, not all those in the practice participated. As a consequence of these two factors, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the similarities in missed care between those working in the acute sector and those in general practice.

There are calls for an expanded role in general practice nursing. If this is to occur, more nuanced understandings of their role, how it is distinguished out from other community nurses and what they are currently rationalising, needs to be understood.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data were generated or analysed during this study.

References

Blackman I, Henderson J, Willis E, Hamilton P, Toffoli L, Verrall C, Abery E, Harvey C (2014) Factors influencing why nursing care is missed. Journal of Clinical Nursing 24(1–2), 47-56.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Blackman I, Palese A, Davielis M, Vryonides S, Henderson J, Willis E, Papastavrou E (2020a) Why nursing care is missed? Findings of a bilateral study. Reasons of Missed Nursing Care. Igiene e Sanita Pubblica 76(6), 355-369.

| Google Scholar | PubMed |

Blackman I, Henderson J, Weger K, Willis E (2020b) Causal links associated with missed residential aged care. Journal of Nursing Management 28(8), 1909-1917.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Bragadóttir H, Kalisch B, Brergthoora G (2016) Correlates and predictors of missed nursing care in hospitals. Journal of Clinical Nursing 26(11–12), 1524-1534.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2), 77-101.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Buchini S, Quattrin R (2012) Avoidable interruptions during drug administration in an intensive rehabilitation ward: improvement project. Journal of Nursing Management 20(3), 326-334.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Castner J, Wu YWB, Dean-Baar S (2014) Multi-level model of missed nursing care in the context of hospital merger. Western Journal of Nursing Research 37(4), 441-461.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Chiappinotto S, Papastavrou E, Efstathiou G, Andreou P, Stemmer R, Ströhm C, Schubert M, de Wolf-Linder S, Longhini J, Palese A (2022) Antecedents of unfuinished nursing care: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Nursing 21(1), 137-160.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Cho SH, Kim YS, Yeon KN, You SJ, Lee ID (2015) Effects of increasing nurse staffing on missed nursing care. International Nursing Review 62(2), 267-274.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Dabney B, Kalisch B (2015) Nurse staffing levels and patient-reported missed nursing care. Journal of Nursing Care Quality 30(4), 306-312.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Dehghan-Nayeri N, Shali M, Navabi N, Ghaffari F (2018) Perspectives of oncology unit nurse managers on missed nursing care: a qualitative study. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing 5(3), 327-336.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Doherty AJ, Atherton H, Boland P, Hastings R, Hives L, Hood K, James-Jenkinson L, Leavey R, Randell E, Reed J, Taggart L, Wilson N, Chauhan U (2020) Barriers and facilitators to primary health care for people with intellectual disabilities and/or autism: an integrative review. BJGP Open 4(3), bjgpopen20X101030.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Dowling M, Beauchesne M, Farrelly F, Murphy K (2013) Advanced practice nursing: a concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing Practice 19, 131-140.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Drach-Zahavy A, Srulovici E (2019) The personality profile of the accountable nurse and missed nursing care. Journal of Advanced Nursing 75, 368-379.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Ebright PR (2010) The complex work of RNs: implications for healthy work environments. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 15(1), Manuscript 4.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gaffney T, Hatcher B, Milligan R (2016) Nurses role in medical error recovery: an integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing 25, 906-917.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gittner LAS, Husaini BA, Hull PC, Emerson JS, Tropez-Sims S, Reece MC, Zoorob R, Levine RS (2015) Use of six sigma for eliminating missed opportunities for prevention services. Journal of Nursing Care Quality 30(3), 254-260.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Haddaway NR, McGuinness LA, Pritchard CC (2021) PRISMA 2020: R package and ShinyApp for producing PRISMA 2020 compliant flow diagrams. (Zenodo). doi:10.5281/zenodo.4287834

Halcomb E, Fernandez R, Ashley C, McInnes S, Stephen C, Calma K, Mursa R, Williams A, James S (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on primary health care delivery in Australia. Journal of Advanced Nursing 78(5), 1327-1336.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, Gagnon M, Griffiths F, Nicolau B, O’Cathain A, Rousseau M-C, Vedel I (2018) Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright (# 1148552). Available at http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf

Kalisch B (2006) Missed nursing care: a qualitative study. Journal of Nursing Care Quality 21(4), 306-313.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kalisch B, Kyung HL (2010) The impact of teamwork on missed nursing care. Nursing Outlook 58(5), 233-241.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Kalisch BJ, Landstrom GL, Hinshaw AS (2009) Missed nursing care: a concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 65(7), 1509-1517.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Labrague LJ, de los Sanots JAA, Fronda DC (2022) Factors associated with missed nursing care and nurse-assessed quality of care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Nursing Management 30(1), 62-70.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Litchfield IJ, Bentham LM, Lilford RJ, Greenfield SM (2014) Test result communication in primary care: clinical and office staff perspectives. Family Practice 31(5), 592-597.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Lubbe W, Ham-Baloyi W, Smit K (2020) The integrative literature review as a research method: a demonstration review of research on neurodevelopmental supportive care in preterm infants. Journal of Neonatal Nursing 26(6), 308-315.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ludlow K, Churruca K, Mumford V, Ellis LA, Braithwaite J (2020) Staff members’ prioritisation of care in residential aged care facilities: a Q methodology study. BMC Health Service Research 20, 423.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Madahar M (2015) Nurse practitioners and practice nurses: different skills, different roles, and both valuable primary care resources. Available at https://www.croakey.org/nurse-practitioners-and-practice-nurses-different-skills-different-roles-and-both-valuable-primary-care-resources/

McInnes S, Peters K, Bonney A, Halcomb E (2015) An integrative review of facilitators and barriers influencing collaboration and teamwork between general practitioners and nurses working in general practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing 71(9), 1973-1985.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

McInnes S, Halcomb E, Ashley C, Kean A, Moxham L, Patterson C (2022) An integrative review of primary health care nurses’ mental health knowledge gaps and learning needs. Collegian 29(4), 540-548.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Moura ECC, Lima MB, Peres AM, Lopez V, Batista MEM, Braga FDCSAG (2020) Relationship between the implementation of primary nursing model and the reduction of missed nursing care. Journal of Nursing Management 28, 2103-2112.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Palese A, Ambrosi E, Prosperi L, Guarnier A, Barelli P, Zambiasi P, Allegrini E, Bazoli L, Casson P, Marin M, Padovan M, Picogna M, Taddia P, Salmaso D, Chiari P, Marognolli O, Canzan F, Gonella S, Saiani L (2015) Missed nursing care and predicting factors in the Italian medical care setting. Internal and Emergency Medicine 10(6), 693-702.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Phelan A, McCarthy S (2016) Missed Care: Community Nursing in Ireland. University College Dublin and the Irish Nurses and Midwives Organisation, Dublin. Available at https://www.justeconomics.co.uk/uploads/reports/Just-Economics-Missed-Care-in-the-Community-Report.pdf

Phelan A, McCarthy S, Adams E (2017) Examining missed care in community nursing: a cross section survey design. Journal of Advanced Nursing 74(3), 626-636.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Phelan A, McCarthy S, Adams E (2018) Examining the context of community nursing in Ireland and the impact of missed care. British Journal of Community Nursing 23(1), 34-40.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Poghosyan L, Norful AA, Fleck E, Bruzzese JM, Talsma AN, Nannini A (2017) Primary care providers’ perspectives on errors of omission. Journal of the Americian Board of Family Medicine 30(6), 733-742.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Schubert M, Glass TR, Clarke SP, Aiken LH, Schaffert-Witvliet B, Sloane DM, De Geest S (2008) Rationing of nursing care and its relationship to patient outcomes: swiss extension of the International Hospital Outcomes Study. International Journal for Qualilty in Health Care 20(4), 227-237.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Schubert M, Clarke SP, Glass TR, Schaffert-Witvliet B, De Geest S (2009) Indentifying thresholds for relationships between the impact of rationing of nursing care and nurse- and patient-reported outcomes in Swiss hospitals: a correlation study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 46, 884-893.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Schubert M, Ausserhofer D, Desmedt M, Schwendimann R, Lesaffre E, Li B, De Geest S (2013) Levels and correlates of implicit rationing of nursing care in Swiss acute care hospitals–a cross sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 50, 230-239.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Senek M, Robertson S, Ryan T, Sworn K, King R, Wood E, Tod A (2020) Nursing care left undone in community settings: results from a UK cross-sectional survey. Journal of Nursing Management 28, 1968-1974.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Senek M, Robertson S, Ryan T, Tod A, King R, Wood E, Taylor B (2021) Missed care in community and primary care. Primary Health Care 32(2), e1692.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Stephen C, McInnes S, Halcomb E (2018) The feasibility and acceptability of nurse-led chronic disease management interventions in primary care: an integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 74(2), 279-288.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Tubbs-Cooley HL, Pickler RH, Mark BA, Carle AC (2015) A research protocol for testing relationships between nurse workload, missed nursing care and neonatal outcomes: the neonational nursing care quality study. Journal of Advanced Nusing 71(3), 632-641.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Verrall C, Abery E, Harvey C, Henderson J, Willis E, Hamilton P, Toffoli L, Blackman I (2015) Nurses and midwives perceptions of missed nursing care – a South Australian study. Collegian 22(4), 413-420.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Verrall C, Willis E, Henderson J (2023) Practice nursing: a systematic literature review of facilitators and barriers in three countries. Collegian 30(2), 254-263.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Vázquez-Sánchez MA, Jiménez-Arcos M, Aguilar-Trujillo P, Guardiola-Cardenas M, Damián-Jiménez F, Casals C (2020) Characteristics of recovery from near misses in primary health care nursing: a prospective descriptive study. Jounral of Nursing Management 28, 2007-2016.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Whittemore R, Knafl K (2005) The integrative review: updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 52(5), 546-553.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Zelenikova R, Drach Zahavy A, Gurkiva E, Papastavrou E (2019) Understanding the concept of missed nursing care from a cross-cultural perspective. Jounral of Advanced Nursing 2995-3005.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Zuniga F, Ausserhofer D, Hamers JPH, Engberg S, Simon M, Schwendimann R (2015) The relationship of staffing and work environment with implicit rationing of nursing care in Swiss nursing homes–a cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies 52(9), 1463-1474.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |