Endangered Kangaroo Island dunnarts are partially arboreal and use pygmy-possum nest boxes

Sophie Petit A B * and Peter A. Hammond B

A B * and Peter A. Hammond B

A

B

Keywords: arboreal, bushfire recovery, Cercartetus, Kangaroo Island dunnart, nest box, refuge, shelter sharing, Sminthopsis fuliginosus aitkeni.

Kangaroo Island (KI) is a biodiversity and endemism hotspot (Crisp et al. 2001; Guerin et al. 2016). Following the 2019–2020 wildfires that burnt nearly 50% of the island (Government of South Australia 2020), a project involved the deployment of 413 pygmy-possum nest boxes (555 cavities) and 347 bat boxes. It aimed to determine the role of nest boxes in bushfire recovery (KI Nest Box Project 2024). The University of South Australia animal ethics permit was RA-04-20, and the Department of Environment and Water Permit series was U26951.

The wooden boxes were deployed in 2020–2021 on 13 properties including burnt, unburnt, and mixed burnt and unburnt ones (Petit et al. 2022). Twelve of the 13 properties were situated in the western half of KI and were monitored up to twice per year until January 2024. Six of the western properties were in the possible range of the KI dunnart (Sminthopsis fuliginosus aitkeni), Critically Endangered under the IUCN (Van Weenen 2008) and Endangered under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) and the South Australia’s National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972. The species has been recorded in eucalypt habitats of western KI that have experienced a spectrum of fire histories. It shelters in burrows and vegetation (Gates 2011), but its ecology is otherwise poorly understood.

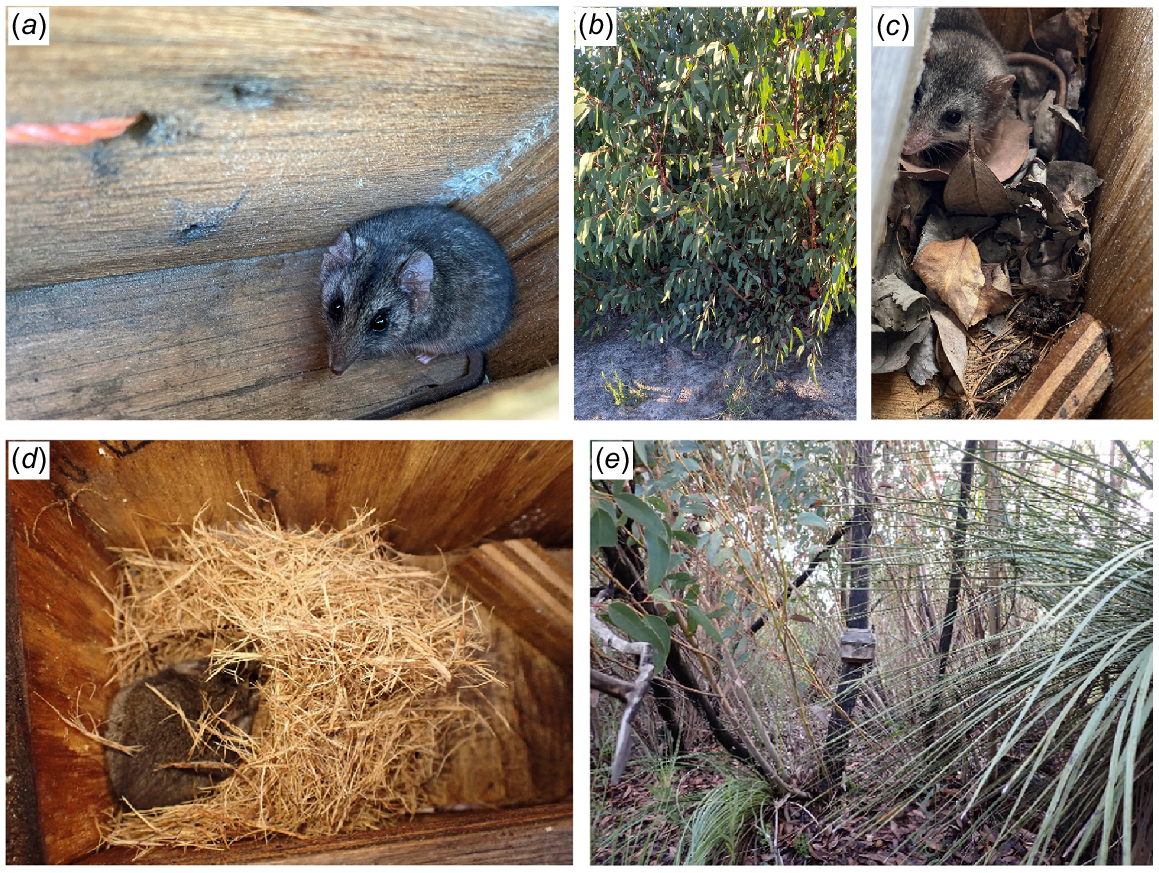

In April 2022 and January 2023, we found a KI dunnart in two different boxes on the same burnt property in the known core range of the species, at Karatta; we do not know if it was the same animal. We opened another box on that property in July 2025; it contained a dunnart resting in fine shredded wood (Fig. 1; box information in Supplementary material file S1). Based on these few observations, we suggest that S. f. aitkeni uses hollows and is partially arboreal. Dickman (1991) indicated some above-ground foraging on mainland Australia by Sminthopsis griseoventer (syn. fuliginosus) and Sminthopsis dolichura, the latter with 1.5% of foraging observations in tree hollows.

(a) Kangaroo Island dunnarts (Sminthopsis fuliginosus atkeni) in wooden pygmy-possum box YMS 0009, 16 April 2022, (b) attached to Eucalyptus remota, and (c) in plywood pygmy-possum box KRP 0012, 9 January 2023. The leaves and fine shredded wood (seen at the bottom of photograph c) are of uncertain origin and could have been placed in the box by Cercartetus concinnus and C. lepidus, respectively. However, the presence of a Kangaroo Island dunnart in a nest made of fine shredded wood (d) in box KRP 0011, 11 July 2025 suggests the species may create this nesting material. The habitat for this box appears in (e).

All woodland species of carnivorous marsupials that have been studied line their nests with materials such as leaves, bark, or feathers (Baker and Dickman 2018). We have 31 records of variations on ‘shredded bark’ substrate descriptions in 19 boxes, including a bat box at 308 cm above the ground, and leaves were common in nest boxes. Sympatric western pygmy-possums (Cercartetus concinnus) make nests of leaves, as we observed on KI, and little pygmy-possums (Cercartetus lepidus, Near Threatened on KI), may make shredded bark nests, as they do in Tasmania (Harris 2009). However, Tasmanian C. lepidus are likely to pertain to a different species from that on the mainland (Osborne and Christidis 2002). Consequently, it is difficult to determine what nests were made or used by which species. Nevertheless, our observation indicates shredded wood is used by S. f. aitkeni and nest construction warrants confirmation with, for instance, video surveillance at box entrances and inside boxes if possible. The nocturnal KI dunnart can use nest boxes as shelters, but may forage on invertebrates in boxes (e.g. ants, Petit et al. 2022, and spiders, commonly found in boxes), or even vertebrates as Antechinus species learn to do (Baker and Dickman 2018). Nest boxes can create unexpected threats to users, such as predation and competition, and the interactions and behaviours of coexisting and competing residents including dunnarts, pygmy-possums, and invertebrates need further research. Nest boxes could be used to study the arboreal habits and nesting ecology of the KI dunnart, provided they do not have detrimental impacts on potential occupants (e.g. possible out-competition of C. lepidus by C. concinnus depending on entrance size (Petit, Hammond, and Bancan, unpubl. data).

Data availability

Data are presented in the paper; additional data are being used for further research.

Declaration of funding

The greater Nest Box Project was funded by the Foundation for National Parks and Wildlife, the Nature Foundation SA Wildlife Recovery Fund Grants Programme, the University of South Australia’s Vice Chancellor’s fund for Kangaroo Island, WIRES-Landcare, Landcare Led Bushfire Recovery from the Australian Government’s Bushfire Recovery Program for Wildlife and their Habitat, the Friends of Private Bushland, Nalda Hoskins, the Albert and Barbara Tucker Foundation, Patagonia (Tides Foundation) under the hospices of the University of South Australia (S. Petit), Kangaroo Island Wildlife Network (K. Welz), Kangaroo Island Conservation Landowners Association (P. Martin and I. Macfarlane), Friends of Parks Kangaroo Island Western Districts (C. Wilson), and Kangaroo Island Research Station (M. B. Stonor).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the spiritual connection of the Narungga, Ngarrindjeri, and Kaurna peoples to Kangaroo Island. We thank the amazing volunteers (J. and J. Bancan, M. Bennell, S. Booth, A. Buick, C. and G. Casey, M. Curth, T. Curth-Stritzke, C, Danis, J. and K. Harris, J. Haska, the Karran family, C. Lapeyre, D. Laver, I. Macfarlane, J. Martin, P. Martin, B. Maxwell, W. Omen, M. Prideaux, A. Robinson, N. Saraswati, B. Somerfield, M. B. Stonor, A., J., and N. Sullivan, M.-A. Swan, R. Wandel, K. Welz, R. Williams, C. Wilson), the many generous box builders (individuals and Community Sheds), and the fabulous landholders.

References

Crisp MD, Laffan S, Linder HP, Monro A (2001) Endemism in the Australian flora. Journal of Biogeography 28(2), 183-198.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Government of South Australia (2020) Lessons from the Island – an independent review of the fires that burnt across Kangaroo Island during December 2019 – February 2020. Government of South Australia, CFS, and C3 Resilience. Available at https://resources-production.safecom.sa.gov.au/current/docs/lessons-from-the-island.pdf

Guerin GR, Biffin E, Baruch Z, Lowe AJ (2016) Identifying centres of plant biodiversity in South Australia. PLoS ONE 11(1), e0144779.

| Crossref | Google Scholar | PubMed |

Harris JM (2009) Cercartetus lepidus (Diprotodontia: Burramyidae). Mammalian Species [842] 1-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

KI Nest Box Project (2024) Kangaroo Island nest box project – finalist, 2024 Eureka prize for innovation in citizen science. Australian Museum. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tu1sQ6bpd7M [accessed 8 April 2025]

Osborne MJ, Christidis L (2002) Systematics and biogeography of pygmy possums (Burramyidae: Cercartetus). Australian Journal of Zoology 50(1), 25-37.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Petit S, Hammond PA, Heterick B, Weyland JJ (2022) Polyrhachis femorata (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) habitat and colony defensive immobility strategy. Australian Journal of Zoology 70(4), 126-131.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Van Weenen J (2008) Sminthopsis fuliginosus ssp. aitkeni. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: e.T20294A9183297. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T20294A9183297.en [accessed 25 May 2025]