Confirmation of green turtle (Chelonia mydas) foraging grounds in northern New Zealand

Brittany Finucci A B * , Matthew R. Dunn A , Clinton A. J. Duffy C , Mark V. Erdmann D , Melanie Hayden E and Irene Middleton A F

A B * , Matthew R. Dunn A , Clinton A. J. Duffy C , Mark V. Erdmann D , Melanie Hayden E and Irene Middleton A F

A

B

C

D

E

F

Abstract

The green turtle (Chelonia mydas) is the only sea turtle species to reside year-round in New Zealand waters, with juveniles using shallow coastal habitats as foraging grounds before dispersing throughout the Pacific. Rangaunu Harbour in northern New Zealand was surveyed in the austral summer to assess the feasibility of aerial drones for monitoring green turtles. Across 163 km of drone transects, 27 turtle sightings representing potentially 18 unique individuals were recorded, predominantly in shallow seagrass (Zostera muelleri novozelandica) habitats during high tides. Five green turtles were observed actively foraging on floating seagrass and among the subtidal seagrass beds. These sightings provide visual confirmation that the harbour is a temperate neritic foraging ground for green turtles in New Zealand. The survey also documented diverse marine fauna, including eagle rays (Myliobatis tenuicaudatus), stingrays (Bathytoshia spp.), and several teleost species, confirming the feasibility of drones as a monitoring tool for turtles and other marine megafauna. Anthropogenic pressure to estuaries and coastal New Zealand ecosystems, including Rangaunu Harbour, highlight the need to identify and protect critical green turtle habitat in New Zealand waters as soon as possible. Further drone surveys in nearby harbours are feasible and recommended to locate additional foraging areas for green turtles across northern New Zealand.

Keywords: aerial drone, aerial survey, diet, habitat use, protected species, seagrass, South Pacific, tidal harbour.

The green turtle (Chelonia mydas) is one of five sea turtle species found in Aotearoa/New Zealand, from Rangitāhua/Kermadec Islands in the north, to Waitaha/Canterbury in the south (Dunn et al. 2022). Green turtles occurring in New Zealand waters are believed to have mixed origins from southwest and East Pacific rookeries (Gill 1997; Godoy 2016). Protected under the New Zealand Wildlife Act of 1953, the green turtle is the only turtle species to occur in New Zealand waters year-round. Juvenile green turtles are presumed to inhabit shallow, sheltered harbours and coastal waters as a temperate intermediary habitat prior to dispersing across the southwest Pacific to reproductive and other tropical feeding grounds (Godoy 2016).

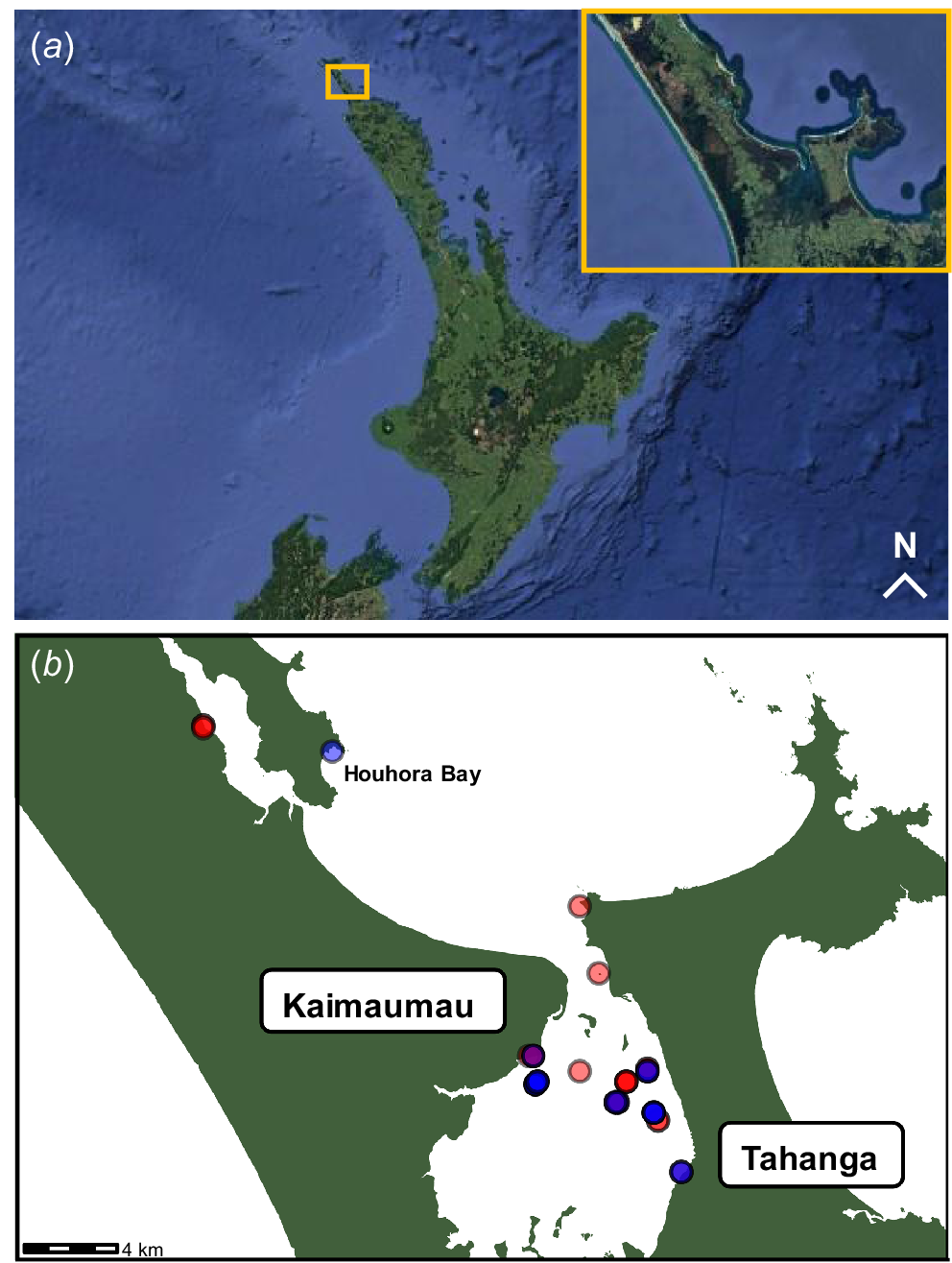

Rangaunu Harbour, located in the far northeast of New Zealand’s North Island (34° 57′S, 173° 15′E, Fig. 1), is a relatively large harbour (115 km2) recognised for its significant natural character (DOC 2005; Kerr 2015). It contains New Zealand’s largest mangrove (Avicennia marina australasica) forest, comprising 15% of the country’s total mangrove area, as well as relatively intact fringing saltmarsh habitats and extensive areas of intertidal and subtidal seagrass (Zostera muelleri novozelandica) (May 1999; Kerr 2015). Its intact estuarine habitats, particularly the subtidal seagrass beds, support high biodiversity and serve as crucial nursery and feeding areas for juvenile coastal fish (Morrison et al. 2014). The seagrass beds are also suspected to be important foraging areas for green turtles (Godoy et al. 2016).

(a) Study site location in relation to the North Island of New Zealand; (b) location of green turtle observations. Blue circles indicate drone transect start locations where at least one turtle was observed, and red circles indicate drone transects where no turtles were observed. Figure part (a) created with Google Earth Pro version 7.3.6.10201.

Northland’s coastal habitats face increasing anthropogenic pressures, including habitat loss and degradation from sedimentation and runoff (Kerr 2015). Sedimentation has led to mangrove encroachment (Morrisey et al. 2007) and reduced seagrass habitat (Morrison et al. 2009). Coastal development, introduced species, and recreational activities such as boating and fishing also disrupt coastal ecosystems, with introduced black swans known to significantly reduce seagrass biomass (Dos Santos et al. 2012). These cumulative impacts may threaten green turtles in Rangaunu Harbour and throughout Northland. Thus, there is a need to identify habitats of importance to the species in New Zealand waters, and for ongoing monitoring of human impacts on these habitats.

In January 2025, a pilot aerial drone survey led by the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research assessed the feasibility of using drones to monitor green turtles in Rangaunu Harbour. High-resolution 4K video footage was captured from an altitude of 30 m while flying at 10 to 12 m/s using commercially available DJI Mavic Pro and DJI Mavic 3 Pro drones. The drone camera was angled 90° vertically. Drone transects were flown along set bearing in a straight line from the starting position (‘home-base’) to a maximum distance (e.g. a land boundary) or to half the battery capacity. Once at maximum distance the drone was turned 90° and moved a minimum of 100 m oblique to the original transect line. The drone was then run back to the start point on a reverse bearing to the outward transect. If turtles were observed, the drone was lowered so that distinguishing features and behaviours could be captured. Data on position, habitat type, and environmental conditions were recorded during the flights for all turtle sightings, and sightings of other species of interest.

A total of 50 drone transects (13 shore-based and 37 vessel-based) totalling 163 km (range: 340–4400 m per transect, mean = 1660 m) were conducted over 4 days. Green turtles were detected along 18 transects – 2 shore-based and 16 vessel-based – resulting in 27 confirmed observations and two unconfirmed sightings (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). The latter were due to identification uncertainty because of water depth, clarity or reflectance. Post-survey review of drone footage identified potentially 18 unique individual green turtles, with up to 10 individuals recorded in a single day. Individual turtles were distinguished by carapace shape and size, barnacle patterns, and other notable features (e.g. scarring). Turtle size was visually estimated using the known field of view of the drone camera. Five of the 29 observations did not show sufficient characteristics for individual identification because the turtles did not surface or were too small in the frame. Turtles were observed on both the western (Kaimaumau, 42%) and eastern (Tahanga, 35%) sides of the harbour, with one location nicknamed the ‘Turtle Bowl’ yielding nine sightings (Fig. 1b). Remaining (23%) sightings were observed in transit, or in the harbour channels, and one individual was observed just outside the harbour entrance and another near the mussel farm in Houhora Bay, approximately 12 km northwest of Rangaunu Harbour. Most sightings (67%, n = 20/29) occurred within 2 h on either side of high tide, predominantly in the morning.

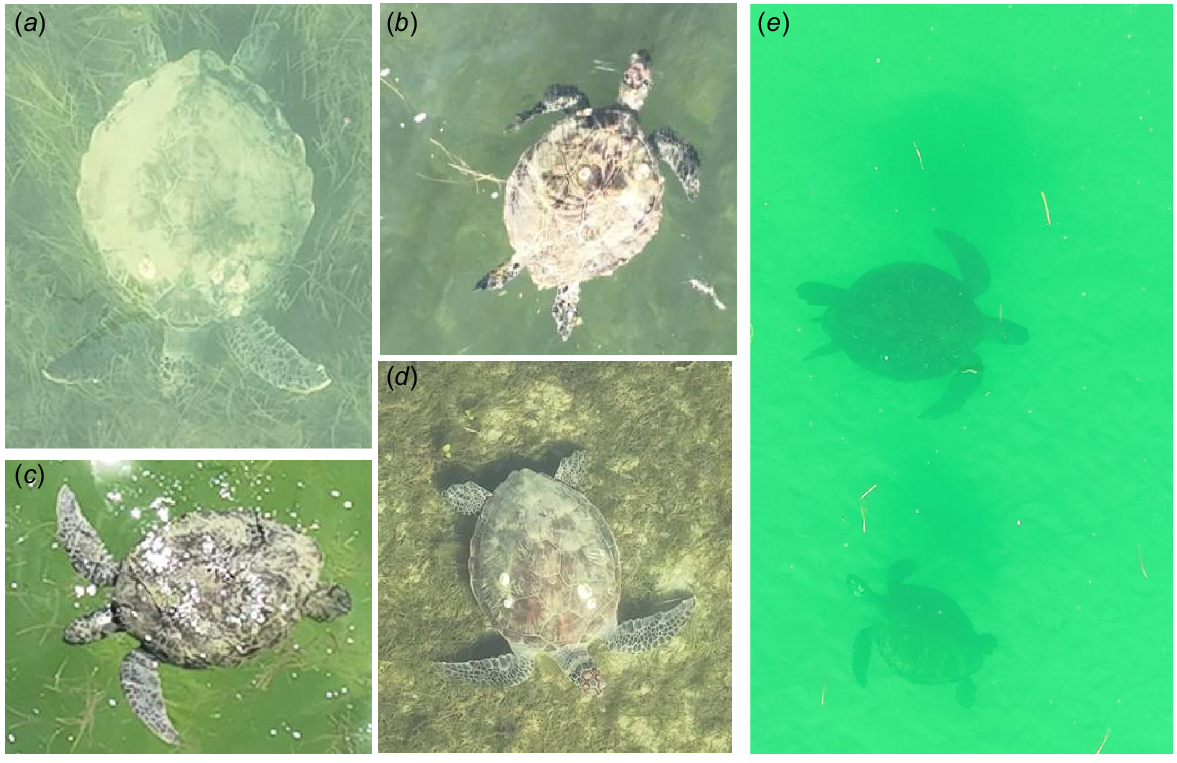

Five green turtles were observed feeding on floating seagrass at the surface and among the subtidal seagrass primarily in shallow waters (~2.5 m) (Fig. 2a–d). These sightings provided visual confirmation that the harbour is a temperate neritic foraging ground for green turtles. Foraging behaviour was generally observed on the eastern side of the harbour. Most of the turtles observed were likely to be immature juveniles and sub-adults based on approximate visual estimates of carapace length (50–100 cm). One larger mature male (approximately 125 cm carapace length) was recorded. There were three occasions where two turtles were observed in close proximity to each other, with one observation of the two turtles (a juvenile and sub-adult) interacting (Fig. 2e).

Examples of (a, d) green turtles feeding on intertidal seagrass subsurface and (b, c) at the surface and (e) observed interaction between a juvenile and sub-adult turtle.

In addition to the 29 green turtle observations, the drone surveys also recorded frequent sightings of eagle rays (Myliobatis tenuicaudatus, n = 357), short-tail stingrays (Bathytoshia brevicaudata, n = 61), and long-tail stingrays (B. lata, n = 28). Potential eagle ray courtship behaviour and high densities of ray feeding pits were also observed. Additional species including snapper (Chrysophrys auratus), kingfish (Seriola lalandi lalandi), bronze whaler shark (Carcharhinus brachyurus), kahawai (Arripis trutta), and trevally (Pseudocaranx dentex) were also recorded.

Green turtles examined from both strandings and fisheries bycatch from northern New Zealand (latitudes 34.6°−37.7° S) have generally ranged from immature juveniles to large sub-adults. Necropsies of these turtles revealed 40 prey taxa (Godoy 2016). Gut contents of most (85%) turtles contained recently ingested neritic but not pelagic prey, suggesting year-round inshore foraging, even at low water temperatures during austral winter-spring months (June to October). Key gut content items included seagrass, mangrove, green algae (Codium fragile), red algae (Sarcothalia atropurpurea), and the sea slug (Pleurobranchaea maculata) (Godoy 2016). Interestingly, P. maculata was identified as the source of tetrodotoxin poisonings and dog mortalities along Auckland Beaches in 2009 (McNabb et al. 2009). Godoy (2016) suggested green turtles may maintain an omnivorous diet to maximise growth and compensate for reduced hindgut fermentation efficiency at lower temperatures. It was not clear if the submerged turtles observed were feeding on seagrass, or on other associated benthic biota. Pleurobranchaea maculata appeared to be abundant in mangrove habitats during a scoping trip in March 2024, but was absent in January 2025, indicating seasonal variability in its availability. It is possible that green turtles in the harbour may maintain a more herbivorous diet during the warmer summer months and rely more on the presence of P. maculata during cooler months. Repeated drone observations of green turtle feeding behaviour, linked with habitat and biodiversity data across seasons, could provide insight into diet partitioning and foraging behaviour.

Rangaunu Harbour is confirmed as a foraging ground for green turtles in northern New Zealand. Satellite-tracked rehabilitated turtles have shown extensive movements around the North Island, particularly near Great Exhibition Bay and the Bay of Islands (D. Godoy, unpubl. data), suggesting additional foraging areas likely exist. Seagrass habitats have been documented throughout northern New Zealand, including nearby Parengarenga Harbour, Whangaroa Harbour, and throughout the Bay of Islands (SeaSketch 2024), locations where green turtles have been sighted (Dunn et al. 2022). Further drone surveys combined with passive tracking of wild individuals are recommended to clarify habitat use, foraging behaviour, home ranges, and environmental drivers (Christiansen et al. 2017). The development of a photo-identification database could improve understanding of turtle residency patterns and population size in New Zealand waters, while also fostering community engagement through the reporting of turtle sightings (Reisser et al. 2008). Stable isotope analysis could further reveal temporal shifts in diet, individual specialisation, ecological niches, and site fidelity (Haywood et al. 2019). Together, these methods would advance understanding of New Zealand’s role as a southern foraging limit for green turtles in the Pacific – one which could increase in importance with predicted future ocean warming (Behrens et al. 2025).

Data availability

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of funding

This study was funded the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) Strategic Science Investment Fund and by MAC3 Impact Philanthropies.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation, BF, MRD, IM, CAJD, MVE; data curation, BF, IM; formal analysis, BF, IM; funding acquisition, BF, MRD, IM, MH; investigation, BF, MRD, IM, MH, CAJD, MVE; methodology, BF, MRD, IM, MVE; visualisation, BF, IM, MVE; writing – original draft, BF; writing – review and editing, BF, MRD, IM, MH, CAJD, MVE. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nina Raharuhi (Ngāti Kahu Hapū cultural monitor, Haitiatimarangai Marae) and Kahurangi Raharuhi for participating in the survey. Thanks to Paul Mills, Jakson Stancich, Marcus Mabee, and Damon Finucci for their insight and logistical support, and to MAC3 Impact Philanthropies for financial support of MVE’s drone survey work. This project was completed through NIWA’s Iwi-link Projects initiative, funded by Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE)’s Strategic Science Investment Fund.

References

Christiansen F, Esteban N, Mortimer JA, Dujon AM, Hays GC (2017) Diel and seasonal patterns in activity and home range size of green turtles on their foraging grounds revealed by extended Fastloc-GPS tracking. Marine Biology 164(1), 10.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

DOC (2005) Near Shore Marine Classification System. Compiled by Vince Kerr for Northland Conservancy. Department of Conservation. Revised 6 September 2005. Available at https://ref.coastalrestorationtrust.org.nz/site/assets/files/8448/doc_2005_northland_nearshore_classification.pdf

Dos Santos VM, Matheson FE, Pilditch CA, Elger A (2012) Is black swan grazing a threat to seagrass? Indications from an observational study in New Zealand. Aquatic Botany 100, 41-50.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Haywood JC, Fuller WJ, Godley BJ, Shutler JD, Widdicombe S, Broderick AC (2019) Global review and inventory: how stable isotopes are helping us understand ecology and inform conservation of marine turtles. Marine Ecology Progress Series 613, 217-245.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Gill BJ (1997) Records of turtles and sea snakes in New Zealand, 1837–1996. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 31, 477-486.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Godoy DA, Smith ANH, Limpus C, Stockin KA (2016) The spatio-temporal distribution and population structure of green turtles (Chelonia mydas) in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 50, 549-565.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

May JD (1999) Spatial variation in litter production by the mangrove Avicennia marina var. australasica in Rangaunu Harbour, Northland, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 33, 163-172.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McNabb P, Mackenzie L, Selwood A, Rhodes L, Taylor D, Cornelison C (2009) Review of tetrodotoxins in the sea slug Pleurobranchaea maculata and coincidence of dog deaths along Auckland Beaches. Prepared by Cawthron Institute of the Auckland Regional Council. Auckland Regional Council Technical Report 2009. 108 p.

Morrison MA, Jones EG, Parsons DP, Grant CM (2014) Habitats and areas of particular significance for coastal finfish fisheries management in New Zealand: A review of concepts and life history knowledge, and suggestions for future research. New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No. 125. 202 p.

Reisser J, Proietti MC, Kinas P, Sazima I (2008) Photographic identification of sea turtles: method description and validation, with an estimation of tag loss. Endangered Species Research 5, 73-82.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

SeaSketch (2024) SeaSketch. Available at https://www.seasketch.org [accessed 25 June 2025]