Tribute to Dr Marina Tyndale-Biscoe (neé Szokoloczi); entomologist and conservationist (27 January 1936–12 July 2025)

Denis A. Saunders A *

A *

A Retired.

Marina Szokoloczi was born in Budapest shortly before the Second World War. She spent her early years on Horka, her parents’ forested estate in Slovakia. As a result, her childhood was lived under the shadow of war and the political unrest that followed. While she and Kyra, her elder sister, were protected by their parents from many of the dangers associated with the times, they must have sensed what was happening around them. Otto, her father, was involved with managing his forests and associated timber business, while Molly, her mother, cared for relatives and the local families who worked in their business. Her parents had to walk a delicate path between the demands of the occupying German forces and those of the partisans living in the forests, who they secretly supported. Otto also gave shelter in his forests to frightened Jews fleeing the Gestapo; an extremely dangerous and courageous thing to do. On one occasion, Otto was arrested by the Gestapo. However, he was subsequently released, probably because he was too useful as a producer of much-needed timber. Marina inherited from her father his quiet strength and gentle courteous nature, and from her mother, determination to succeed in whatever she set her mind to.

After the war, the communist government of Slovakia forced her parents off their estate with no compensation. In 1949, the family migrated to Australia, settling in Tasmania. Marina loved Kopanica, their new home in rural Tasmania, where she quickly came to appreciate the beauty of the Australian landscape and its associated biota. She did not like the boarding school in Melbourne she and Kyra were sent to, a dislike that provided the impetus to learn English and finish school as fast as possible. She quickly became fluent in English, however, throughout her life she spoke English with an engaging accent. Her love of nature led her to study science, and by 1958 Marina had completed a Zoology Honours degree at the University of Tasmania, which she was able to undertake on a university bursary. The subjects of her Honours thesis were chitons she collected on the southern tip of Bruny Island. On graduating, she took up a position as a demonstrator studying aphids at the Waite Institute, Adelaide University.

In 1959, Marina attended the annual conference of the Australian and New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science in Perth. On the second day of the conference, she met Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe, who was conducting research for his PhD at the University of Western Australia. By the end of the conference they had decided to get married, which they did in Tasmania in February 1960. They flew to Perth the day after their wedding, and then to Rottnest Island for a working honeymoon catching quokkas (Setonix brachyurus) for Hugh’s PhD research.

Marina took up a position at the Western Australian Museum, working on pebble crabs, and published her research on their taxonomy in Tyndale-Biscoe and George (1962). Marina and Hugh’s son Simon was born in October 1961. Shortly after, the family moved to Canberra where Hugh took up a position in the Zoology Department of the Australian National University. Soon after settling in Canberra, their daughter Nicola and son Paul arrived in quick succession and Marina was a full-time mother with three children under three.

In 1964/65, the family spent a sabbatical year in St Louis, USA, for Hugh’s research. In mid-1965, on returning from St Louis, Marina shocked her contemporaries by leaving her children in the care of Tante Ulla, a lovely German woman, and returning to research full-time at the CSIRO Division of Entomology. For the next 5 years she studied bushflies as part of a large research team. At that time, bushflies were a serious health pest for humans in the summer months in Canberra and most of Australia. Because of this, in Canberra, it was illegal for restaurants to serve food outside. Marina conducted research to determine the physiological age of adult female bushflies. With this knowledge, it was possible to determine where bushflies went in winter. Because of her research, at the Division of Entomology, she was referred to as ‘the ageing lady’.

In Canberra and surrounding regions in New South Wales, bushflies die off each autumn. Colonists are blown south from breeding areas in Queensland each spring to re-establish the population. Their breeding success depends on the quantity and quality of fresh cow dung. The key to bushfly control was to disperse the dung. This required imaginative field work as described by Marina in 1967: ‘[we] drove north to Cunnamulla in Queensland looking for bushflies…since it’s still winter the flies are only active in the middle of the day. So, we tried to get to our catching area by noon and then proceed in a leisurely way to build a fire and grill a chop, which attracts the flies. We then caught them in nets…Every evening we sat up until 11 or so, dissecting the flies we had caught that day, and by this method we could establish which flies were migrating southwards and which ones were already established and breeding. It was most interesting and an absolute tonic for a holiday. Hugh and the children seemed to get on fine. Tante Ulla had run the household beautifully.’ (Marina Tyndale-Biscoe in litt.).

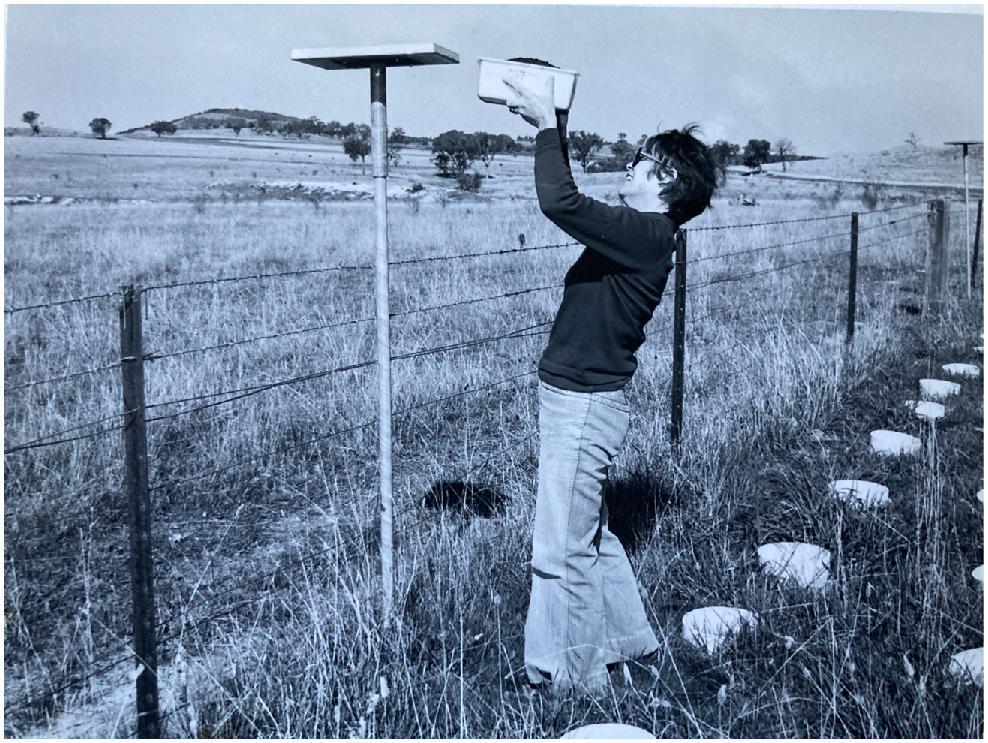

In 1971, the family spent another sabbatical year abroad, this time in Cali, Colombia. On returning to Canberra, Marina re-joined CSIRO, becoming part of a different research program. Native dung beetles cannot break down large cow pats. In 1967, CSIRO began to introduce African dung beetles that were able to break down cow dung and bury it. From 1973 until 1992, Marina was part of a large team that progressively introduced many species of foreign dung beetles and assessed their suitability for controlling bushflies in south eastern Australia and Tasmania (Fig. 1). As a result of that program, Canberra and many other parts of Australia, are now relatively free from bushflies and al fresco dining has become a common pleasure. In 1990, Marina wrote Common Dung Beetles in Pastures of South-East Australia (Tyndale-Biscoe 1990, CSIRO Publishing, reprinted in 2001) that described the features and distribution of the most successful of the introduced species of dung beetles to help farmers select the best ones for their area. Following her redundancy from CSIRO in 1992, she returned part-time taking part in a Double Helix Project helping children identify dung beetles collected on their properties and thereby plotting the emerging distribution of the various introduced species in south eastern Australia.

Marina Tyndale-Biscoe setting up an experiment on dung beetles and bushflies in the late 1970s. She placed cow pats on the ground and elevated on platforms to establish that both were visited by bushflies, but dung beetles only visited those on the ground (photograph Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe).

Her bushfly research was published in a series of papers in the Bulletin of Entomological Research (Tyndale-Biscoe and Hughes 1969; Tyndale-Biscoe 1971, 1978, 1983, 1984, 1989; Tyndale-Biscoe and Kitching 1974; Vogt et al. 1974; Hughes et al. 1978; Tyndale-Biscoe and Vogt 1996), as well as forming the first chapter of her PhD thesis at James Cook University (Tyndale-Biscoe 1985).

In 1980, Marina and Hugh bought a property they called Yarabal by the Mongarlowe River, near Braidwood, New South Wales. To Marina, this was fulfilling her childhood dream of living in the country. They established a pine plantation, maintained a small herd of cattle, and revegetated the degraded native forest. Marina grew waratahs (Telopea spp.) for the Braidwood Market. In 1990, on the bank of the Mongarlowe River, they built a beautiful, rammed-earth house in which they lived for the next 25 years. Marina discovered how to propagate the local Monga waratah and for several years sold plants at the Yarralumla Nursery in Canberra. She also planted another species, the Braidwood brilliant and for many years each October produced a large crop of flowers for the Braidwood Market.

In 1980, together with Judith Wright, an Australian poet and environmentalist, Marina was a founding member of the Friends of Mongarlowe River. The group was established to protect Monga Forest, the river, and its headwaters from logging and mining. She brought her scientific mind to the group, using hair tubes to establish what species of small mammals existed in the forest. She demonstrated the presence of two endangered species, the long-nosed potoroo (Perameles nasuta) and the tiger quoll (Dasyurus maculatus). Their presence was crucial evidence supporting the establishment of Monga National Park.

Marina’s mother kept a diary of the family’s brave and challenging lives during German and Soviet occupation of Slovakia during and after the Second World War. Her father was unaware at the time his wife was keeping a diary. After they had migrated to Tasmania, when he found out about the diary, he was initially appalled at the risk she had taken, but subsequently added his recollections to Molly’s account. In 2014, together with Meredith McKinney, Marina edited and published these records as Horka – a home that was: Surviving in Czechoslovakia 1938 to 1949. As the last surviving member of her family who migrated to Australia in 1949, Marina became the custodian of her family’s archives. In 2024, her family records, along with those of her scientific research and public activities, were accepted into the Archives of the National Library of Australia. Together they paint a picture of a remarkable woman (Fig. 2).

Marina’s last years were dogged by ill-health. She developed emphysema, which was terminal, a fate she accepted with equanimity. She died peacefully in Canberra, surrounded by her family. Marina’s was a well-lived life, conducted on her terms, and in her quiet, unstated way her work on bushflies and dung beetles had a major impact on the life style of many Australians. She is survived by Hugh, her husband of 65 years, her three children, and five grandchildren.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Dr Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe AM for providing details of Marina’s private and professional life and to Emeritus Professor Harry Recher AM for critical comments on an earlier draft of this tribute.

References

Hughes RD, Tyndale-Biscoe M, Walker J (1978) Effects of introduced dung beetles (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) on the breeding and abundance of the Australian bushfly, Musca vetustissima Walker (Diptera: Muscidae). Bulletin of Entomological Research 68(3), 361-372.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tyndale-Biscoe M (1971) Protein-feeding by the males of the Australian bushfly Musca vetustissima Wlk. in relation to mating performance. Bulletin of Entomological Research 60(4), 607-614.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tyndale-Biscoe M (1978) Physiological age-grading in females of the dung beetle Euoniticellus intermedius (Reiche) (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Bulletin of Entomological Research 68(2), 207-217.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tyndale-Biscoe M (1983) Effects of ovarian condition on nesting behaviour in a brood-caring dung beetle, Copris diversus Waterhouse (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Bulletin of Entomological Research 73(1), 45-52.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tyndale-Biscoe M (1984) Adaptive significance of brood care of Copris diversus Waterhouse (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Bulletin of Entomological Research 74(3), 453-461.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tyndale-Biscoe M (1989) The influence of adult size and protein diet on the human-oriented behaviour of the bush fly, Musca vetustissima Walker (Diptera: Muscidae). Bulletin of Entomological Research 79(1), 19-29.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tyndale-Biscoe M, George RW (1962) The Oxystomata and Gymnopleura (Crustacea, Brachyura) of Western Australia with descriptions of two new species from Western Australia and one from India. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 45(3), 65-96.

| Google Scholar |

Tyndale-Biscoe M, Hughes RD (1969) Changes in the female reproductive system as age indicators in the bushfly Musca vetustissima Wlk. Bulletin of Entomological Research 59(1), 129-141.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tyndale-Biscoe M, Kitching RL (1974) Cuticular bands as age criteria in the sheep blowfly Lucilia cuprina (Wied.) (Diptera, Calliphoridae). Bulletin of Entomological Research 64(2), 161-174.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Tyndale-Biscoe M, Vogt WG (1996) Population status of the bush fly, Musca vetustissima (Diptera: Muscidae), and native dung beetles (Coleoptera: Scarabaeinae) in south-eastern Australia in relation to establishment of exotic dung beetles. Bulletin of Entomological Research 86(2), 183-192.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Vogt WG, Woodburn TL, Tyndale-Biscoe M (1974) A method of age determination in Lucilia cuprina (Wied.) (Diptera, Calliphoridae) using cyclic changes in the female reproductive system. Bulletin of Entomological Research 64(3), 365-370.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |