The human and social impacts of an Australian mouse plague

Lucy Carter A * , Kerry Collins

A * , Kerry Collins  A , Aditi Mankad A , Walter Okello B and Peter R. Brown

A , Aditi Mankad A , Walter Okello B and Peter R. Brown  C

C

A

B

C

Abstract

From mid-2020 until the end of 2021, a significant mouse plague affected areas of Southern Queensland, Western Victoria, South Australia and regional New South Wales (NSW). In 2023, 2 years after this event, a team of social scientists visited regional NSW farming communities and businesses to document the human and social impacts of this catastrophic event.

Whereas scientific knowledge of the impacts of rodent incursions on broader farming systems and ecosystems has advanced, social research to address the human dimensions of mouse plagues has been sparse. We describe and detail the human and social impacts of the 2021 NSW mouse (Mus musculus) plague.

A series of interviews, focus group discussions and informal conversations were conducted across selected regional NSW locations. The data collected were analysed using latent content analysis technique. Our methodological design addressed numerous ethical issues raised by fieldwork in this setting.

Five key themes were uncovered from the data. (1) The social and human impacts of plagues are broad and deep. (2) Plagues are inevitable, sudden, and inseparably linked to existing livelihood pressures. (3) The desperation and despair created by plagues affect individuals, families and communities with vulnerable populations at most risk of lasting harm. (4) Targeted assistance along with government recognition of the widescale impacts of plagues is sought by communities. (5) Curiosity and support for novel technologies to reduce mouse numbers is high along with real-time information platforms to predict and manage outbreaks.

Our research has provided insights into the extensive human and social impacts of plague events, beyond the usual boundaries of plagues in the context of farming system impact or zoonotic disease transmission. We offer recommendations for agencies and service providers to better support rural communities to prepare for and recover from future outbreaks.

Current research on rodent outbreaks is firmly embedded in agricultural and ecological domains. The breadth of impacts of Australian mouse plagues signals the existence of a much more complex system. This research goes some way in providing a social impact perspective to a problem typically recognised as agricultural.

Keywords: human impacts, invasive pests, mouse plague, qualitative research, rodent outbreak, rural NSW, social dimensions, social research.

Introduction

Plagues of house mice (Mus musculus) in rural and regional Australia are recurring events, typically influenced by climatic disruption and largely affect crop and pasture growing areas of south-eastern Australia (Saunders and Robards 1983). Mice typically cause significant crop damage by feeding on seed or newly emerging seedlings, consuming unharvested grain, resulting in reduced yield, chewing plants, and damaging or contaminating stored grain and fodder (Saunders and Robards 1983; Singleton and Redhead 1989; Mutze 1993; Caughley et al. 1994; Brown and Henry 2022).

From mid-2020 until the end of 2021, a significant mouse plague affected areas of Southern Queensland, Western Victoria, South Australia and regional New South Wales (NSW) (White et al. 2024). Emerging observations from this event point to widespread system-level effects, including impacts on landscapes and ecosystems, plus significant economic, human and social impacts (Randall-Moon 2024; White et al. 2024). The full extent of these impacts is still being uncovered.

In rural and regional contexts, identifying rodent outbreaks as influencing a broader socio-economic system is not yet commonplace in the literature. System-orientated approaches such as One Health are helping to reshape impact and management discussions, although interdisciplinary cooperation is still developing (cf. Carter et al. 2024; White et al. 2024). Similarly, the social sciences and humanities have for decades contributed to system-level understanding of invasive species conceptually, theoretically and empirically (White et al. 2008; White and Ward 2010; Head 2017; Carter et al. 2021). Yet, in the context of Australian mouse plagues, research on the human dimensions remains limited (White et al. 2024). With few exceptions (cf. Caughley et al. 1994; White et al. 2008), most contributions have typically considered impacts on humans through the lens of agricultural systems and often in the context of on-farm economic loss (cf. Singleton et al. 2007; Brown et al. 2010; Bradshaw et al. 2021). Through this lens, crop production industries experience the largest economic impact of rodent outbreaks (Caughley et al. 1994; Brown and Henry 2022).

Of the human dimensions-led contributions, much of the discussion remains confined to improving farmers’ responses to monitoring and reducing mouse population build-up and preventing zoonotic disease risk (cf. Buckle and Pelz 2015; Donga et al. 2022; Schulze Walgern et al. 2023). One notable exception has been the capturing of community-based narratives shared through digital media during the 2021 NSW plague (Randall-Moon 2024). The media discourse analysis showed strong themes related to human vulnerability, a sense of lack of control over the environment, and the human response to animal death, including killing animals over time (Randall-Moon 2024).

Emerging evidence suggests that the pervasiveness of rodents enables them to intrude in all aspects of people’s lives and homes and presents significant human, social and mental health impacts, rendering rodent outbreaks unlike other agricultural pest incursions (White et al. 2024; Mankad A, Collins K, Okello W, Carter L, Brown PR, unpubl. data). The impacts of mouse plagues on mental health have yet to be fully investigated although evidence points to mouse plagues generating a high level of human stress (Singleton and Redhead 1989; Caughley et al. 1994; Mankad A, Collins K, Okello W, Carter L, Brown PR, unpubl. data). Similar stress responses have been observed in landholders defending livestock from wild dog attacks (Ecker et al. 2017). Given the human experience of acute stress, loss, disruption to social networks and general threat to wellbeing, parallels have been made with impacts of other catastrophic events such as natural disasters (Shams 2021; White et al. 2024; Mankad A, Collins K, Okello W, Carter L, Brown PR, unpubl. data).

Internationally, research on impacts of rodent outbreaks is mixed. Much of the literature similarly focusses on impacts related to farming systems and ecosystem health, and this work has helped inform how outbreaks are monitored and managed (Capizzi et al. 2014). Situating rodent outbreaks as instances of human–wildlife conflict has additionally raised questions about the role of human values and behaviour in wildlife management (cf. Lauret et al. 2020; Zufiaurre et al. 2021). More broadly, efforts to eradicate rodents from ecologically important landscapes by using novel biotechnologies, has attracted some debate on the role of humans in conservation efforts to reduce biodiversity loss (Howald et al. 2007; Leitschuh et al. 2018). With some exceptions from urban experiences across disadvantaged settings in North America and South Africa (cf. German and Latkin 2016; Shah et al. 2018; Byers et al. 2019; Chelule and Mbentse 2021), the lived experiences of communities during plague events are not well documented.

Improving our knowledge of the human dimensions of plagues allows for governments, organisations and communities to better plan for, respond to and recover from significant outbreaks. The current study sought to fill this gap by sharing contextualised and contemporary knowledge of the human and social dimensions of a catastrophic Australian mouse plague. Characterised by widespread incursion, suddenness and cumulative effects on wellbeing, we join colleagues in describing the 2021 event as ‘catastrophic’ (White et al. 2024). The findings shared here are among the few Australian studies to document the experiences of regional communities living through a modern mouse plague. The work invites consideration of mouse plagues as a broader ecological problem strongly embedded in complex social, cultural and institutional systems.

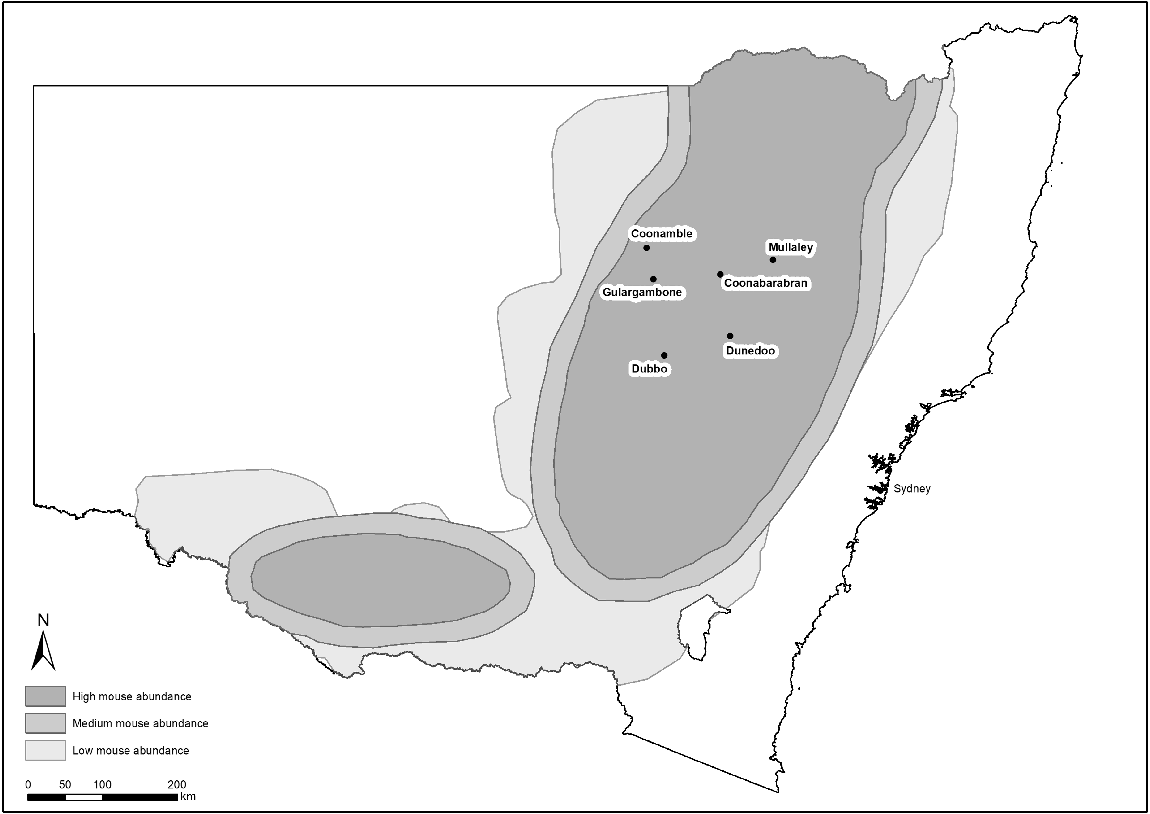

This paper reports on the findings from a mix of organised focus group discussions and informal community conversations held across Dunedoo, Mullaley, Coonabarabran, Gulargambone, and Coonamble over a 1-week period in May 2023 (Fig. 1). The data were supplemented by a series of expert interviews undertaken prior to the field work, which informed contextual understanding of the 2021 event.

Research locations overlayed with the approximate location of the mouse plague across NSW at its peak in March 2021. Source: CSIRO (2021).

Methods

Methodological approach

The team faced several ethical challenges in planning the research that required employing an adaptive, reflexive approach to methodological design, an important consideration for undertaking qualitative research in socially and politically sensitive contexts (Fenge et al. 2019; Savin-Baden and Major 2023). The risks associated with triggering distress when asking communities to recite impact stories, the presence of existing community vulnerability and hardship, and our lack of strong connection to location specific issues all presented ethical challenges to navigate through methodological design (Shaw et al. 2019; Reich 2021). For example, ahead of fieldwork the research team learned that for many regional NSW communities, recovery was ongoing with affected communities continuing to experience ongoing financial and mental health impacts. General dissatisfaction with the government’s response to the plague along with frustration with the recent reduction in drought support was also evident in some communities. Given the research team was metropolitan based, had not previously experienced a mouse plague, and had not recently been connected to regional and rural issues, a research protocol was developed with these sensitivities in mind. In addition to this research context, data collection took place at a time when communities were still recovering from continued disruptions raised by drought and COVID-related lockdowns. Our visits were planned around local flooding events, seasonal farming calendars and the availability of local community mediators who could assist to facilitate community participation. Our sampling, recruitment and data collection strategy described below reflects these methodological challenges. The study design follows a grounded theory approach where data collection and analysis are iterative, reflective and contextualised processes (Charmaz and Thornberg 2021).

Sampling and recruitment

In May 2023, a team of four social, economic and behavioural scientists converged in Dubbo, NSW, to conduct community conversations across select plague-affected regional towns (Fig. 1). Five regional NSW localities were selected for study – Dunedoo, Mullaley, Coonabarabran, Gulargambone and Coonamble. Some of these towns were identified as among the worst to be affected by the 2021 event. The team travelled by road between each locality to conduct focus group discussions (FGDs). Impromptu conversations with staff from local organisations and businesses were also sought, most of which were conducted between or after scheduled FGD sessions, as opportunities arose. Table 1 shows the various data collection points used in this study. The total data set comprised data collected from 23 FGDs, 20 unstructured conversations and 7 structured online expert interviews. The following subsections provide a more detailed explanation of each data collection point.

| Location | Data collection points | Social and livelihood roles of participants engaged in regional NSW | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Online | Seven individual interviews with experts across key sectors | Individual interviews: health, community, government, research, agronomy, grains export, veterinary. | |

| Dunedoo | Eight discussion groups, across two time periods Unplanned conversations with local businesses (‘impromptu visits and walks’) | Group discussions: teachers, mothers, health services staff, local trades personnel, agribusiness suppliers and retailers, local business owners, community support workers, urban amenities staff, mixed farming, cattle producer, croppers. Impromptu conversations: council amenities staff, retail business operator, builder, agricultural brokering business, livestock and grain farmer, food retail outlets. | |

| Mullaley | Four discussion groups | Group discussions: mixed farming; cereal cropping; grain producer; cotton farmer; beef producers; livestock plus cropping farmer; mixed grain farmer; fodder cropper; livestock mixed farming; women farmers; community members. | |

| Coonabarabran | Three discussion groups Planned and unplanned conversations with local businesses and organisations | Group discussions: farmers; mixed farming operators; beef producers; livestock producers including cropping; mixed grain producer; rural agricultural suppliers; construction workers; homeowners. Impromptu conversations: school staff, local business operator, tourism operator. | |

| Gulargambone | Three discussion groups | Group discussions: farming households, retail business staff, agricultural input suppliers, tourism operators, local residents. Impromptu conversations: veterinarians, food retailer. | |

| Coonamble | Five discussion groups, across two time periods Planned and unplanned conversations with local businesses and organisations | Group discussions: vehicle servicing operators, mixed farming, cattle producer, grazier, herder, feedlot worker, emergency services personnel, transport operator, mothers, agronomists, allied health worker, female householders. Impromptu conversations: agronomist, food retailers, local business owners, veterinarians. | |

| Dubbo | Planned interview with grains exporter |

The team recruited a field coordinator with deep local knowledge and extensive networks to assist with participant recruitment and to create safe spaces for community members to share their impact stories. A ‘safe space’ in this context refers to the provision of a physically inclusive and comfortable venue, as well as a socially and culturally familiar space to share personal stories (McCosker et al. 2001). To help facilitate this environment, the coordinator engaged a local community liaison mediator at each location to provide a connection between the local community and the research team. In total, four community liaison mediators along with one mental health support professional volunteered their time to assist with recruitment and data collection.

The mediators were tasked with recruiting individuals and businesses to attend FGD sessions, providing a central contact point for local community and media enquiries, and helping the research team connect with community members on arrival at each session. The assistance of local mediators was fundamental to orienting the research team to current local issues and community sentiments. This information informed the development of FGD discussion questions and allowed the research team to mentally prepare for visiting severely affected towns.

Mediators used a combination of purposive and snowball sampling techniques to recruit residents to the FGD sessions. Purposive and snowball techniques apply non-probabilistic strategies to deliberately select participants who hold specific knowledges, attributes or interests relevant to the topic under study (Moser and Korstjens 2018). Diverse representation across age, gender, and livelihood was sought by mediators. Care was taken to ensure that a cross-section of the community was recruited, with the research team guiding the process via a research protocol and regular meetings. The protocol contained key study design details as well as a facilitators’ guide for managing emotionally difficult situations during community discussions, in line with best practice when conducting sensitive or difficult qualitative research (Darlington and Scott 2020). A decision was made to invite a local mental health counsellor from the NSW Rural Advisory Mental Health Program to remain on standby to assist those participants who were emotionally vulnerable. The protocol became a central reference point for both researchers and mediators and was instrumental in demonstrating consideration of research risks during ethics review.

Multiple session times were offered for attendance to afford participants flexibility in attending a session around work, family, and other commitments. The FGD venues were selected by local mediators. A local cafe, sporting and social clubs, a town hall and a local fire station were among the venues selected for holding community discussions.

In between scheduled FGD sessions, the research team sought opportunities to partake in informal conversations with local business owners and staff from community organisations. A few of these conversations were initiated opportunistically by the team themselves while walking through town centres between sessions. Further information on these exchanges can be found in Table 1. Finally, professional insights were sought via an online platform from representatives across agriculture, policy, health, community, and veterinary practice to orient the research ahead of fieldwork. Further details for this data point are provided in the sections below. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the CSIRO Social and Interdisciplinary Human Research Ethics Committee (179/22).

Data collection

Structured individual interviews (N = 7) were conducted ahead of the fieldwork and had multiple important functions. The interviews were designed to inform the research team of the broader context of the mouse plague and the relevant themes for exploration in the FGDs. The interviews also offered a range of sectoral-based views of the impacts of the 2021 plague, providing important contextual information for interpretation of the topics raised during community conversations. Expert interviews were video recorded online by using Microsoft Teams, which generated a transcription of each interview. Notes were also taken during these discussions to assist with analysis.

The interview schedule for expert interviews included the following: questions about the interviewees’ role during the plague; the diversity and scale of impacts observed at that time; the organisational challenges faced in responding to the plague; and ideas about future prevention and management of plague impacts. Participants engaged for interview were at the time of the 2021 plague employed across government and research sectors, as well as private practice, and had direct experience of supporting regional communities through the plague under various administrative and operational mechanisms.

A series of semi-structured, community-based focus group discussions (N = 23) were held across selected regional NSW towns including Dunedoo, Mullaley, Coonabarabran, Gulargambone, and Coonamble (Table 1). A semi-structured FGD schedule was created and included the following themes for exploration: most significant event or memory from the 2021 plague; impact types and their severity; estimated financial losses; adjustments to family life and livelihoods during the outbreak; coping strategies employed; accessed social and financial supports; observed wider community impacts; and views on managing future mouse plagues.

Each discussion group consisted of four to five participants, with a mix of gender and professional backgrounds represented in each group. Given most participants identified as having multiple public and private roles (e.g. mother and farmer), we chose not to apply individual identity labels to categorise attendees according to single livelihood or social role. Instead, we used general descriptors chosen by participants themselves to describe our FGD cohort.

Participants identified as farmers, including mixed farming and croppers, rural business-owners and managers, allied health and emergency personnel, teachers, food retail staff, retirees, agricultural input suppliers, trades and construction personnel, and mothers (refer to Table 1 for full details). A decision was made to refrain from divulging finer disaggregated information about participants to protect individual identities, especially for residents embedded in small country towns. The discussion groups achieved a good gender balance overall, although representation from young people aged 18–25 years was difficult to achieve. All planned FGDs were audio recorded using digital data recorders, before being transcribed using a third-party transcription service.

In addition to FGDs, a number of loosely planned and impromptu conversations were held during town visits (N = 20). These additional data were gathered through informal conversations with a cross-section of community organisations and local businesses represented.

Many of these informal conversations were initiated on behalf of the researchers by the local mediators who had invited local businesses and organisations to engage with the researchers as we travelled through town. Other conversations were initiated directly by the research team while walking through the centre of town between FGD sessions. Almost all these interactions lasted between 10 and 20 min, a few were up to 1 h in duration (a minimum of two researchers was present during each interaction). No formal notes were taken during these exchanges to maintain the informal conversational style of these interactions, but key themes from these conversations were documented afterwards. Express permission to document the topics of conversation was provided by participants on each occasion after introduction to the research purpose. To preserve confidentiality, we have chosen to only identify the business or organisation type for this data set, given the privacy risk of identifiability in small town locations. A general description of these impromptu conversations across localities is provided in Table 1.

Data analysis

The data collected from both planned FGDs and unstructured conversations are combined in the presentation of results and discussion below. The expert interviews informed the topics explored with communities, while also providing context for making sense of the themes raised during community conversations.

For latent content analysis, a systematic process of interpretation was applied to identify, sort and label codes initially (Kleinheksel et al. 2020). Codes were gradually and iteratively collapsed into categories, which later informed the labelling of higher-order themes. These themes form the discussion below. Strategies used to ensure credibility (i.e. internal validity) included data triangulation, and member checks (via expert and peer conference) (Korstjens and Moser 2018). Transferability was ensured by providing thick descriptions that included research context. Confirmability and reflexivity are demonstrated through the creation of a research protocol and research notes throughout the design and analysis process.

Across all data collection points, participants were asked for their express consent prior to being interviewed. Written consent forms were signed by FGD participants, and those professionals invited for online interview. For informal street-based conversations, verbal consent for participation was sought.

Results and discussion

The research design attracted a mix of farming households, local business operators, members of community organisations, and local residents to share their impact stories. We invited rural residents to self-describe their personal or professional identities when introducing themselves in the group discussions in preference to the research team assigning pre-determined descriptors. This acknowledges the often multiple and intertwined personal and professional roles we all hold in society and becomes particularly saliant when interpreting results, given mouse plagues pervade multiple facets of people’s professional and personal lives (Randall-Moon 2024; White et al. 2024).

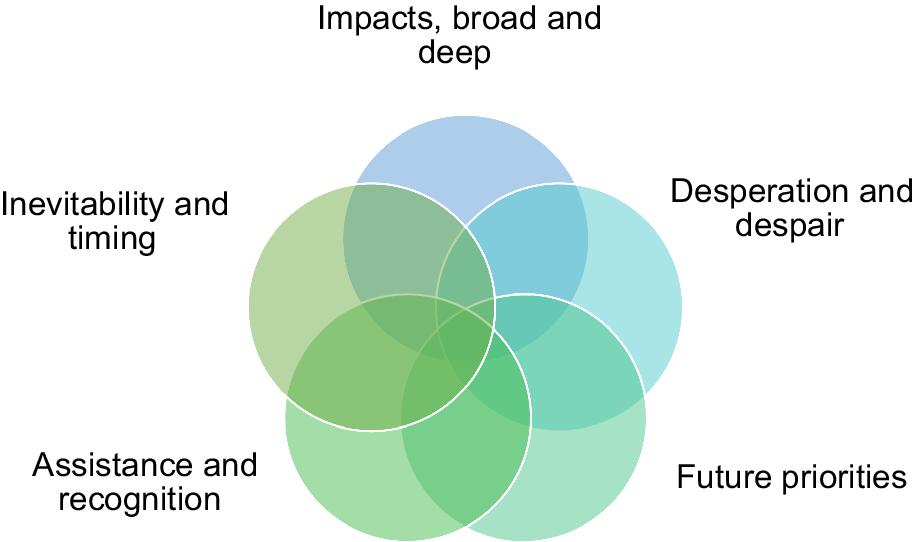

Fig. 2 represents the strongest themes to emerge from analysis across all community-based conversations. Five clear themes surfaced from the data set. Impacts, broad and deep reflects the diverse array of impacts, most of them unquantified in a formal sense, and many not relating directly to farm-related assets. Inevitability and timing describes the near universal acceptance of plagues as a natural recurrence in regional and rural communities; yet, unexpected events such as climate disasters often exacerbate existing challenges and vulnerabilities. Desperation and despair conveys the devastation that mouse incursions can wreak on an individual’s wellbeing, their household, and their community. Assistance and recognition offers regional perspectives on reducing the impacts of future plagues and supporting those most at risk because of pre-existing economic vulnerability and social isolation. Finally, Future priorities describes a general curiosity and support for innovative biocontrol solutions to reduce future plague impacts as well as suggestions for improving plague preparedness.

The five strongest themes to emerge from community-based conversations across regional NSW localities. Descriptions for each of these themes appear below.

These five labels represent the collection of consistently strong themes uncovered during fieldwork across sampled locations. Although distinct labels were selected to describe each theme, there are clear links and some overlap among these. To collapse these further, risks diminishing the richness of the topics uncovered in each theme, running counter to the methodology chosen. Relatedly, no attempt has been made to retrospectively fit these themes into pre-existing state or federal biosecurity and pest management governance frameworks. Although possible, this exercise would require reinterpretation of the dataset and would be likely also to conflict with our chosen methodological approach. Each of these themes are elaborated below.

Impacts of plagues are both broad and deep

The combined data show significant impacts across a range of categories including economic, social, physical, and mental health dimensions. Discussions across all locations showed that the economic impacts of the 2021 plague remain largely uncosted formally by enterprises, including local businesses and individual farmers. Participants who reported economic losses had rough estimates in mind, yet these were largely reported to be related to major on-farm expense categories such as wholesale machinery damage, stock losses owing to mouse damage or expenditure on purchasing bait in bulk. Descriptions of these estimable costs frequently related to production or post-harvest loss in the case of farming enterprises, and stock or labour costs for regional businesses. Similar costs and losses have been observed across previous Australian plagues, which have historically been explored through the lens of agricultural productivity (Caughley et al. 1994; Brown and Henry 2022).

I’d estimate a six-figure sum for baiting costs and crop loss – that’s not easy to budget for. (Mullaley, male)

For retail businesses, mass stock losses across a range of items were reported. Common examples from supermarkets included decimation of perishable and non-perishable human and animal food resulting from mouse contamination. Unexpected product losses included those items used by mice for nesting such as feminine hygiene products. Significant costs were incurred across the board in hiring additional labour for daily cleaning to maintain a sense of cleanliness.

The inescapable stench of dead and dying mice was reported to have a significant impact on customer traffic and staff morale. The unrelenting exposure to putrid stench was also identified in Mankad A, Collins K, Okello W, Carter L, Brown PR (unpubl. data) as having a significant impact on psychological wellbeing and is explored in more detail below in the theme, Desperation and Despair.

Business owners determined a proportion of losses and costs to be recoverable through general business tax deductions, and rebates through the NSW government-initiated Mouse Control Program. However, of note, only a small proportion of community members indicated successfully accessing the rebate program. The reasons offered varied; for farmers it was frequently considered an onerous and costly administrative burden. For residents, not possessing receipts to verify expenses accrued was an identified obstacle. For some, limited access to technology or the confidence to navigate the rebate system online prevented people from accessing any reimbursements offered.

It was just, I don’t know, to make them look good that they’re giving rebates which were totally useless. Hardly anyone would have claimed it because no one had receipts. (Coonamble, male)

For householders, the material impact stories shared contained significant losses across categories not traditionally considered farm related, of which some were also highlighted in Caughley et al. (1994) more than three decades ago. Examples include electrical damage to essential household appliances, and destruction of clothing, manchester, and bedding due to mice nesting and contamination. Among the residents who shared their stories, none indicated that the household damage incurred was eligible for claim under existing insurance policies.

Personal vehicles were reported to have suffered damage related to destruction of electrical wiring and car interiors. These expenses were at times described as the cost of paying tradespeople for their time to identify the direct cause of faults, occasionally without the actual problem ever identified. The delay to onset of faults likely associated with mouse damage was an ongoing source of frustration for some residents.

For schools, health and aged care facilities, the impacts were wide-ranging. Across all community-based organisations, scheduled professional cleaning for mouse contamination became the daily norm for months. School children and staff regularly assisted in the clean-up of mice and stories of competitions to collect the greatest number of dead mice were shared. Our conversations with healthcare professionals identified that mice had been observed to have entered patients’ rooms, nested in wardrobes and crawled over patients during daylight hours.

Costs associated with seeking veterinary care for companion animals affected by accidental poisoning were commonly reported by residents, as was loss to hobby farm livestock, including backyard poultry. Local veterinarians spoke of almost daily visits from pet owners seeking care for direct and indirect exposure to commonly available anti-coagulant rodenticide products, a finding also reported by White et al. (2024).

Other reported social, environmental and community impacts were described as ‘devastating’ for those communities visited. Observed environmental impacts included a visible reduction of predator bird species. This finding aligns with emerging research on the impacts of anticoagulant rodenticides on Australian wildlife (Lohr and Davis 2018; Low et al. 2024; White et al. 2024). The environmental cost of dumping rotting mouse carcases on public land was considered regrettable in worst-affected towns, where local waste disposal services struggled to manage removal.

Across all locations, women and children assumed the burden of cleaning in homes, schools and businesses. Tasks included disposal of dying and decomposing carcases, cleaning and resetting traps, continuous sanitising and disinfection, and vigilant securing of supplies vulnerable to mouse contamination to prevent spoilage. Social impact analysis conducted by Mankad A, Collins K, Okello W, Carter L, Brown PR (unpubl. data) confirmed that women reported experiencing the burden of household related duties related to sanitation. Caughley et al. (1994) similarly reported unrecognised additional burdens on women who assumed responsibility for maintaining clean homes and workplaces.

You cleaned, you cleaned, and you cleaned. (Dunedoo, female)

The impact stories shared across all towns sampled indentified losses and costs not yet formally recognised or visible by agencies whose mandates may in the future better support communities during and after a plague event. Considering the significant response costs identified by participants in this study and Mankad A, Collins K, Okello W, Carter L, Brown PR (unpubl. data), revisiting the roles and resourcing of public and civil society organisations to response to significant outbreaks is warranted.

Inevitability of plagues and the matter of timing

This theme relates to the perceived unpredictable pace of plague development, its onset in farming cycles, across seasons and climatic conditions, and the importance of timeliness in prediction and preparedness for a range of sectors. Community conversations identified an almost universal acceptance of mouse plagues being a part of regional and rural life, especially among farming communities. The absence of disagreement among participants on the causes and contributors to plague events is notable, and contrasts with research on rodent outbreaks internationally, which have reported significant community disagreement about outbreak origins, which can compromise management (Lauret et al. 2020).

Linked to the acceptance of the inevitability of plagues, was the belief that no matter how many mice were trapped or baited at an individual or household level, no significant impact in decreasing mouse numbers overall was ever achieved. Participants consistently recalled feeling they were simply exercising some control over their immediate environment by killing mice, or that they had a moral responsibility to contribute to the collective effort of reducing mouse numbers. Similar feelings of powerlessness and dismay have also been observed in urban Canadian communities where rat infestations are prevalent, affecting the mental and physical wellbeing of residents (Byers et al. 2019).

When a plague comes you don’t control it. You’ve got to wait for it. You’ve got to manage it for your best interests until it passes, and that’s all. (Dunedoo, male)

The centrality of timing in this theme relates to the uncertainty of outbreaks, the mixed quality of information available to take decisive action on farm, and the risks involved in making decisions during critical times in the production cycle. Farming families in our cohort mentioned the emotional difficulty of securing the first good harvest post-drought while being faced with the risk of losing stored grain to mouse inundation. The link between climate shifts and plague events has previously been noted in the media (Australian Geographic 2021; Scientific American 2021) and research is continuing to understand these links better (cf. Andreassen et al. 2021).

Balancing the pressures of maintaining agricultural livelihoods in uncertain economic conditions, while managing significant climate disruption during a catastrophic mouse outbreak, was considered by some participants an experience from which they would likely not be able to recover if such events were to recur.

You can write your crop off in a week. (Mullaley, male)

We don’t have time to do mouse plagues. (Coonamble, male)

Agriculture is exhausted now. (Mullaley, male)

I think that’s what everyone [feels] – I hear it all the time. I don’t think I could do it again. That’s what people say. I don’t think I could do this again. (Dunedoo, female)

The issue of timing was also raised in relation to rebate accessibility, with participants remarking that the government program could have been available much earlier. Timing was additionally a strong theme in relation to accessibility and reliability of bait and traps supply. For many respondents, the decision to use poisons and baits off-label, was a decision directly attributable to supply shortage, and the subsequent inflationary pricing of chemicals. In this context, we refer to ‘off-label use’ as the unapproved and potentially unsafe use of baits and poisons by farmers and residents during a mouse plague. Our preference for adopting ‘off-label’ over other more common descriptions such as ‘indiscriminate use’, overuse’ or ‘misuse’ reflects our intention to avoid normative judgements, which tend to imply poor decision making and irresponsibility on the part of farmers. Human behaviour around off-label use is complex and in the case of outbreak, considered an absolute last resort to regain some sort of control in catastrophic circumstances. Off-label use in this context is unlikely to be a problem related to literacy or carelessness and was often the only option available for some residents to prevent total inundation. We explore this topic further in the theme Desperation and Despair below. Perhaps unsurprisingly, local innovation was evident in the design and manufacture of water bucket traps, which became a popular and cost-effective tool for residents to reduce mouse numbers during the height of the outbreak.

Finally, timing was mentioned in relation to the unreliability of commercial aerial baiting services during critical times in the lead up to the outbreak. A shortage of both aircraft and pilots, along with the prohibitive cost of aerial drops for some, was considered influential to outbreak mitigation capacity. Accurate prediction of future outbreaks remains a priority research focus for Australian institutions, especially as the benefits of preparedness extend beyond the traditional borders of the farming system (Pech et al. 2015).

Desperation and despair are common experiences during plague

The Desperation and despair theme speaks to the intense and often pervasive mental, physical and emotional toll this plague event had on people and their communities. This study was conducted nearly 2 years after the 2021 NSW event and, for some communities, the horrors of the 2021 event remain intense. Two topics were raised consistently under this theme; the first is the inescapability of mouse exposure during plague and the effects this has on human wellbeing. The experience of mouse incursion differs somewhat from natural disasters like drought or locust plagues, where retreat may be found inside one’s home, at least temporarily. Mice can infiltrate every aspect of a person’s personal space including kitchens, bedrooms, bathrooms, family rooms, and personal vehicles making people’s immediate environment feel unsanitary, unsafe and, in some cases, create hypervigilance.

There’s an anxiety. If you listen to people talking, […] the mice are back. The mice are back. It’s almost mentally preparing themselves to go into this battle again. (Dunedoo, female)

You become quite psychotic. You just want to get rid of them. It’s awful. (Dunedoo, female)

Turning nice women into murderers. I could easily pick them up by the tail and smack it against the tree. (Mullaley, female)

Which is how the end comes around, so that’s actually quite exciting when you see them going for each other, you’re like it’s almost over, yes. (Referring to mouse cannibalism as a sign to nearing end of outbreak) (Mullaley, male)

The second significant topic under this theme was the ubiquitous stench of decomposing carcases, mouse droppings and live mice during the months of outbreak. The stench was described as all-pervasive, affecting personal mood and outlook, as well as relationships and social connections. Descriptors for the odour commonly used in impact stories included ‘putrid’, ‘rotting’ and ‘unbearable’. The negative psychological, emotional and in some cases physical effects of odour nuisance have previously been documented in diverse environmental and industrial contexts including flying fox incursions in urban areas, agricultural and industrial processing, wastewater treatment, and urban high-density living (Aatamila et al. 2011; Wojnarowska et al. 2020; Berkers et al. 2021; Salleh 2021).

Householders spoke of feeling embarrassed and ashamed to host visitors in their homes, in some cases avoiding socialising altogether. Business owners shared similar sentiments but expressed some solace in the knowledge that everyone in their vicinity was experiencing the same problem. Travellers and tourists passed through towns quickly, often commenting on the stench while in stores. Cancellation of reservations for holidaymakers was common, affecting local tourism operators.

Sleep deprivation, physical and emotional fatigue, anxiety and shame were among the feelings conveyed by participants to describe their physical and mental health experiences. Interestingly, the topic of infectious disease risk was rarely raised, despite the active efforts of local health authorities to communicate zoonotic risks of rodent-borne infectious disease (NSW Government 2021). Further study on attitudinal factors affecting risk perceptions and the effectiveness of risk messaging in farming communities could be explored. A comprehensive quantitative analysis of the psychological dimensions of living through the 2021 plague has been explored by Mankad A, Collins K, Okello W, Carter L, Brown PR (unpubl. data).

It’s every tiny aspect of your life, there’s nothing left in your life. (Mullaley, female)

The hotel, the caravan park, the supermarket, café, all trying to put the clean face of the business up to the public and the mental strain of watching your presentation of what you love just being slowly eroded from you, no matter the work you put in. (Gulargambone, male)

Finally, stories of displacement, both internal, either via barricading specific rooms in the home for respite, or escaping to other locations entirely, was a common story conveyed among residents in worst-affected areas such as Coonamble and Gulargambone. The latter was available only to those who could access additional resources.

Need for disaster recognition and the right assistance

A repeated request by all communities visited was for governments to recognise catastrophic plague events as natural disasters. Residents believed that disaster recognition would allow for more efficient response and support services to be triggered allowing for faster and more inclusive recovery.

It has to be dealt with exactly the same as a drought, or a fire, and it is really important they understand that. It is a natural disaster. (Coonabarabran, female)

Residents who relied on support for their physical or home care and those with mobility challenges were identified by communities at particular risk. The added complexity of COVID-related lockdowns and health staff shortages exacerbated the impact for many people living with disability during the outbreak. Maintaining adequate sanitation and hygiene after experiencing mouse inundation indoors was not possible for the elderly and less mobile who were entirely dependent on family, friends and neighbours to render assistance.

Aged people […] they can’t bend down to empty the traps, or they can’t lift the bucket. It was just simple little things like that, that old people really struggled with. (Dunedoo, female)

A general dissatisfaction with the regional government response to both plagues and ongoing drought recovery was present in the areas visited. This finding was consistent with the quantitative investigation conducted by Mankad A, Collins K, Okello W, Carter L, Brown PR (unpubl. data). A general sentiment of community abandonment was conveyed across all locations despite the roll-out of various government and community-run campaigns and events designed to provide support (White et al. 2024).

No one has asked us if we’re ok until today. (Gulargambone, female)

It is not possible in this study to attribute the broader sense of dissatisfaction we encountered in communities to any particular department or level of government as people expressed general dissatisfaction and distrust for various reasons, including a lingering dissatisfaction with the federal government’s management of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, streamlining rebate and compensation programs to improve access across the gamut of complex situations and needs was suggested among participants. Cooperation among governments and the private sector to enable greater cost recovery from the full extent of impacts of outbreaks was an expectation among communities visited.

Future priorities for plague mitigation

A final theme uncovered several priorities identified by residents to help reduce the impact of future plagues. Among these priorities was strong support and curiosity for research into novel biotechnologies to reduce mouse abundance in future outbreaks. Although a range of different sterilisation and biocontrol methods was offered as possible candidates for population suppression, the perceived need for a novel and efficient solution was strong. This finding correlates with previous research conducted by the authors indicating willingness among Australians to support the use of novel biotechnologies in the management of invasive pest species, especially when the rationale for doing so is clear (Mankad et al. 2020, 2022).

A biological trial, it’s the only way to go, to be honest, like prickly pear… It just does seem a bit strange that there isn’t a biological solution to mice, because we’ve had them for a fair while, you know what I mean? (Coonabarabran, male)

We need a selective calicivirus that looks after our natives, so our native ones are safe. (Gulargambone, male)

What’s being done in research for biological control and managing and monitoring? I think even people being aware of what’s going on would help them to understand the magnitude of the problem and how it’s being managed at that bigger level. (Dunedoo, female)

More accurate and timely monitoring of mouse movements and consistent messaging from authorities was also raised as a priority, and research to improve prediction methods is now gaining traction (c.f. Brown et al. 2022). Improved advice for the prevention of mouse damage to dwellings was also sought by residents, yet, to our knowledge, no agency has yet assumed responsibility for advising residents on methods to prevent mice home inundation. Although advice from authorities was generally trusted, some frustration was evident among residents who perceived official advice to be at times conflicting. In these cases, neighbours and peers were the most trusted sources of information for dealing with the outbreak.

If you see your neighbour and you [ask], oh, have you got a problem? So it starts there, and once you decide you’ve got a problem then you’ve got to go and find someone else to give information to. (Mullaley, male)

It’ll happen again. They need to do it as soon as an area – I don’t care how big the area is – as soon as an area identifies that they’ve got a lot of mice, they need to do something straight away, not wait. (Coonamble, male)

Across those locations worst affected, including Dunedoo, Coonamble and Gulargambone, there were suggestions for the government to explore avenues for market intervention to protect both supply and pricing of traps and baits, and consider the potential economic loss to businesses faced with excess bait supply once the outbreak passes. Finally, programs to collectivise the cost-sharing and coordination of aerial spraying services was also considered a part solution to outbreak mitigation.

Study strengths and limitations

Whereas this study is one of the first to explore in depth the range of human and social impacts of Australian mouse plagues, there are limitations to interpreting its results. The study was specifically designed to capture rich qualitative data, which are not generalisable. The goal of qualitative research differs from quantitative approaches, in that context and relationships are important study considerations. Repeating this study with other communities might show different stories.

Our data collection took place during a time of regional disruption where local flooding events coincided with harvest time for many farmers. Although community engagement was made possible by the involvement of community liaison mediators, a more favourable time for participation might have attracted additional voices to the discussions. Our sample did lack adequate representation from youth, which might have provided a different perspective during group discussions.

The methodological design used is not suited to research projects with short time frames and inflexible research milestones. The sensitivities we encountered demanded the agility afforded by an adaptive study design and an aligned research funder who trusted the skillset of the research team. Without these enablers in place, the research would not have generated quality data alongside the capacity to manage risks.

Recommendations and conclusions

This research aimed to uncover the human and social impacts of Australian mouse plagues to extend consideration of impacts beyond the lens of on-farm economic costs. Until now, research on plague impacts has been confined to assessing the effects on farming systems, which have yet to include the broader social, cultural and institutional system dimensions of outbreaks.

Australian mouse plagues have traditionally been treated as a problem primarily associated with land use changes and agricultural practices and responsibility for impact mitigation is often placed on individual farmers (Buckle and Pelz 2015; Donga et al. 2022; Schulze Walgern et al. 2023). Once an incursion is underway, there is an expectation that the private sector maintains affordable and reliable supply of rodenticides to manage an outbreak. Additionally, significant pressure is placed on public health authorities to prevent infectious disease exposure and retain safe storage and use of poisons (NSW Government 2021). Yet, this limited conceptualisation of Australian mouse plagues neglects the broader social and institutional context in which impacts occur. Importantly, opportunities to better plan for and coordinate ancillary services to assist communities to recover, may also be missed.

Five strong themes were uncovered from this study, showing a wider set of impacts and influences on regional wellbeing, not detailed since the Caughley et al. (1994) report. Our research found the impacts of the 2021 NSW mouse plague are diverse, extend beyond on-farm costs and are yet to be adequately recognised by relevant agencies and services. Australian mouse plagues occur in complex systems where external disruptive events such as drought can exacerbate existing regional vulnerabilities. Outbreaks affect the wellbeing of individuals, households, businesses, community organisations and communities. Even though regional communities we sampled accept the inevitability of plagues as recurring events, they seek targeted assistance to manage and recover from significant events. A centrally coordinated data repository containing accessible real-time information for speedy decision making was commonly mentioned. Exploration of government-led partnerships with the private sector to secure adequate supply of rodenticides at reasonable cost was also suggested. A general curiosity and interest among regional communities in novel biotechnologies to reduce mouse abundance additionally signals public interest in scientific innovation.

This research has shown that descriptions of rural outbreak impacts, their measurement and their resolve, are in need of a rethink. The impacts of Australian mouse outbreaks, and arguably other agricultural pest outbreaks, occur both on-farm and off-farm and affect regional communities on physical, mental, social, environmental, and financial levels. The types of support identified as required post-outbreak share similarities with the needs of communities recovering from natural disasters. We make three key recommendations for policy and research consideration.

First, better coordination of a breadth of government and non-government services is suggested to ensure that the right support is offered before, during and after a plague event. That support needs to be accessible, well-timed and tailored to the needs of diverse rural populations and their surrounds. A plague event is inescapable for some rural communities. In areas that are severely affected, mice can invade every aspect of a person’s personal, social and working life (Randall-Moon 2024). Mouse outbreaks have devastating effects on rural communities and their surrounding environments (White et al. 2024).

Second, communication about health risks should not be limited to zoonotic infection risks, considering the significant mental and emotional toll outbreaks present. Australian mouse plagues, along with other agricultural pest outbreaks, can no longer be interpreted as a problem confined to the agricultural space, nor the sole responsibility of individual farmers to manage. Although there is a clear role for farming communities to monitor and reduce mouse populations early, the breadth of impacts of outbreaks identified by this work signals the existence of a much more complex system (White et al. 2024).

Some segments of the community are particularly vulnerable to harm, loss and injury during plague. These groups are often reliant on assistance with mobility and physical care and include aged residents unable to maintain the constant cleaning and removal of mice needed to secure a safe home. Social isolation can be worsened during plague. Our final recommendation would be the early identification of potentially vulnerable groups and individuals including targeted and reliable support planning ahead of the next outbreak.

Data availability

The data that support this study cannot be publicly shared owing to ethical and privacy reasons. It is protected under institutional ethics approval conditions issued by the CSIRO Social and Interdisciplinary Science Human Research Ethics Committee.

Conflicts of interest

PRB is an Associate Editor of Wildlife Research but was not involved in the peer review or any decision-making process for this paper. The authors have no further conflicts of interest to declare.

Declaration of funding

This research was funded by the NSW Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development.

Acknowledgements

We are particularly grateful to the communities visited for trusting us with their stories. We also acknowledge the work of our local coordinator and community liaison mediators, Amanda Glasson, Sally Dent, Therese Ryan, Georgie Gavel, Meegan Young and Camilla Herbig, whose support enabled us to connect with communities meaningfully.

References

Aatamila M, Verkasalo PK, Korhonen MJ, Suominen AL, Hirvonen M-R, Viluksela MK, Nevalainen A (2011) Odour annoyance and physical symptoms among residents living near waste treatment centres. Environmental Research 111, 164-170.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Andreassen HP, Sundell J, Ecke F, Halle S, Haapakoski M, Henttonen H, Huitu O, Jacob J, Johnsen K, Koskela E, Luque-Larena JJ, Lecomte N, Leirs H, Mariën J, Neby M, Rätti O, Sievert T, Singleton GR, van Cann J, Vanden Broecke B, Ylönen H (2021) Population cycles and outbreaks of small rodents: ten essential questions we still need to solve. Concepts, Reviews and Syntheses 195, 601-622.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Australian Geographic (2021) A land of flooding plagues: Australia’s history of mice and rat irruptions. Available at https://www.australiangeographic.com.au/topics/wildlife/2021/04/a-land-of-flooding-plagues-australias-history-of-mice-and-rat-irruptions/ [accessed 15 May 2025]

Berkers E, Pop I, Cloïn M, Eugster A, van Oers H (2021) The relative effects of self-reported noise and odour annoyance on psychological distress: different effects across sociodemographic groups? PLoS ONE 16, e0258102.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Bradshaw CJA, Hoskins AJ, Haubrock PJ, Cuthbert RN, Diagne C, Leroy B, Andrews L, Page B, Cassey P, Sheppard AW, Courchamp F (2021) Detailed assessment of the reported economic costs of invasive species in Australia. NeoBiota 67, 511-550.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Brown PR, Henry S (2022) Impacts of house mice on sustainable fodder storage in Australia. Agronomy 12, 254.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Brown PR, Henry S, Pech RP, Cruz J, Hinds LA, van de Weyer N, Caley P, Ruscoe WA (2022) It’s a trap: effective methods for monitoring house mouse populations in grain-growing regions of south-eastern Australia. Wildlife Research 49, 347-359.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Byers KA, Cox SM, Lam R, Himsworth CG (2019) ‘They’re always there‘: resident experiences of living with rats in a disadvantaged urban neighbourhood. BMC Public Health 19, 853.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Capizzi D, Bertolino S, Mortelliti A (2014) Rating the rat: global patterns and research priorities in impacts and management of rodent pests. Mammal Review 44, 148-162.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Carter L, Mankad A, Zhang A, Curnock MI, Pollard CRJ (2021) A multidimensional framework to inform stakeholder engagement in the science and management of invasive and pest animal species. Biological Invasions 23, 625-640.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Carter L, Mankad A, Okello W (2024) Where exactly do the social and behavioural sciences fit in One Health? Frontiers in Public Health 12, 1386298.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Charmaz K, Thornberg R (2021) The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qualitative Research in Psychology 18, 305-327.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Chelule PK, Mbentse A (2021) Rat infestation in Gauteng Province: lived experiences of Kathlehong Township residents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, 11280.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

CSIRO (2021) Monitoring mice in Australia – March 2021. Issue 24. CSIRO and GRDC. Available at https://research.csiro.au/rm/mouse-activity-updates

Donga TK, Bosma L, Gawa N, Meheretu Y (2022) Rodents in agriculture and public health in Malawi: farmers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Frontiers in Agronomy 4, 936908.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Ecker S, Please PM, Maybery DJ (2017) Constantly chasing dogs: assessing landholder stress from wild dog attacks on livestock using quantitative and qualitative methods. Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 24, 16-30.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Fenge LA, Oakley L, Taylor B, Beer S (2019) The impact of sensitive research on the researcher: preparedness and positionality. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 18, 1-8.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

German D, Latkin CA (2016) Exposure to urban rats as a community stressor among low-income urban residents. Journal of Community Psychology 44, 249-262.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Head L (2017) The social dimensions of invasive plants. Nature Plants 3, 17075.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Howald G, Donlan CJ, Galván JP, Russell JC, Parkes J, Samaniego A, Wang Y, Veitch D, Genovesi P, Pascal M, Saunders A, Tershy B (2007) Invasive rodent eradication on islands. Conservation Biology 21, 1258-1268.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Kleinheksel AJ, Rockich-Winston N, Tawfik H, Wyatt TR (2020) Demystifying content analysis. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 84, 7113.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Korstjens I, Moser A (2018) Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. European Journal of General Practice 24, 120-124.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lauret V, Delibes-Mateos M, Mougeot F, Arroyo-Lopez B (2020) Understanding conservation conflicts associated with rodent outbreaks in farmland areas. Ambio 49, 1122-1133.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Leitschuh CM, Kanavy D, Backus GA, Valdez RX, Serr M, Pitts EA, Threadgill D, Godwin J (2018) Developing gene drive technologies to eradicate invasive rodents from islands. Journal of Responsible Innovation 5, S121-S138.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Lohr MT, Davis RA (2018) Anticoagulant rodenticide use, non-target impacts and regulation: a case study from Australia. Science of The Total Environment 634, 1372-1384.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Low Z, Murray PJ, Naseem N, McGilp D, Doneley B, Beale DJ, Biggs L, Gonzalez-Astudillo V (2024) Evaluating sublethal anticoagulant rodenticide exposure in deceased predatory birds of South-East Queensland, Australia. Discover Toxicology 1, 13.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mankad A, Hobman EV, Carter L (2020) Effects of knowledge and emotion on support for novel synthetic biology applications. Conservation Biology 35, 623-633.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mankad A, Zhang A, Carter L, Curnock M (2022) A path analysis of carp biocontrol: effect of attitudes, norms, and emotion on acceptance. Biological Invasions 24, 709-723.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

McCosker H, Barnard A, Gerber R (2001) Undertaking sensitive research: issues and strategies for meeting the safety of all participants. Forum: Qualitative Social Research 2(1), 1-14.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Moser A, Korstjens I (2018) Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: sampling, data collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice 24, 9-18.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Mutze GJ (1993) Cost-effectiveness of poison bait trails for control of house mice in mallee cereal crops. Wildlife Research 20, 445-456.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

NSW Government (2021) Staying healthy during a mouse plague. Available at https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/environment/factsheets/Factsheets/mouse-plague.pdf [accessed 15 May 2025]

Randall-Moon H (2024) The mice plague and the assemblage of beastly landscapes in regional and rural Australia. Sociologia Ruralis 64, 222-236.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Reich JA (2021) Power, positionality, and the ethic of care in qualitative research. Qualitative Sociology 44, 575-581.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Salleh A (2021) Flying foxes increasing in urban areas means more potential conflict with humans. Available at https://www.abc.net.au/news/science/2021-04-25/flying-fox-in-urban-areas-how-to-avoid-conflict-with-humans/100053328 [accessed 17 May 2025]

Saunders GR, Robards GE (1983) Economic considerations of mouse-plague control in irrigated sunflower crops. Crop Protection 2, 153-158.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Schulze Walgern A, Hecker O, Walther B, Boelhauve M, Mergenthaler M (2023) Farmers’ attitudes in connection with the potential for rodent prevention in livestock farming in a municipality in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. Animals 13, 3809.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Scientific American (2021) Australia’s plague of mice is devastating and could get a lot worse. Available at https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/australias-plague-of-mice-is-devastating-and-could-get-a-lot-worse/ [accessed 15 May 2025]

Shah SN, Fossa A, Steiner AS, Kane J, Levy JI, Adamkiewicz G, Bennett-Fripp WM, Reid M (2018) Housing quality and mental health: the association between pest infestation and depressive symptoms among public housing residents. Journal of Urban Health 95, 691-702.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Shams H (2021) Mouse plague impacting NSW residents’ mental health like that of natural disasters, expert says. Available at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-04-26/mouse-plague-impacting-nsw-residents-mental-health/100091634 [accessed 15 May 2025]

Shaw RM, Howe J, Beazer J, Carr T (2019) Ethics and positionality in qualitative research with vulnerable and marginal groups. Qualitative Research 20, 277-293.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Singleton GR, Tann CR, Krebs CJ (2007) Landscape ecology of house mouse outbreaks in south-eastern Australia. Journal of Applied Ecology 44, 644-652.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

White PCL, Ward AI (2010) Interdisciplinary approaches for the management of existing and emerging human-wildlife conflicts. Wildlife Research 37, 623-629.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

White PCL, Ford AES, Clout MN, Engeman RM, Roy S, Saunders G (2008) Alien invasive vertebrates in ecosystems: pattern, process and the social dimension. Wildlife Research 35, 171-179.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

White J, Taylor J, Brown PR, Henry S, Carter L, Mankad A, Chang W-S, Stanley P, Collins K, Durrheim DN, Thompson K (2024) The New South Wales mouse plague 2020–2021: a one health description. One Health 18, 100753.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Wojnarowska M, Sołtysik M, Sagan A, Stobiecka J, Plichta J, Plichta G (2020) Impact of odor nuisance on preferred place of residence. Sustainability 12, 3181.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |

Zufiaurre E, Abba AM, Bilenca D (2021) Damage to silo bags by mammals in agroecosystems: a contribution for mitigating human–wildlife conflicts. Wildlife Research 48, 86-96.

| Crossref | Google Scholar |